Thinking Outside the Basin: Evaluating Israel’s Desalinated Climate Resilience Strategy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. A Very Brief History of Israeli Water Management

“carry out the necessary actions for the early preparation of the economy for seawater desalination, including: promoting the general and detailed planning for the location of desalination facilities; integrating the desalination facilities into the water supply system; reserving land for desalination facilities; and approving the national outline plan for desalination… Tender documents shall be prepared for the construction of a desalination facility using a finance-build-operate method involving private entrepreneurs.”[73]

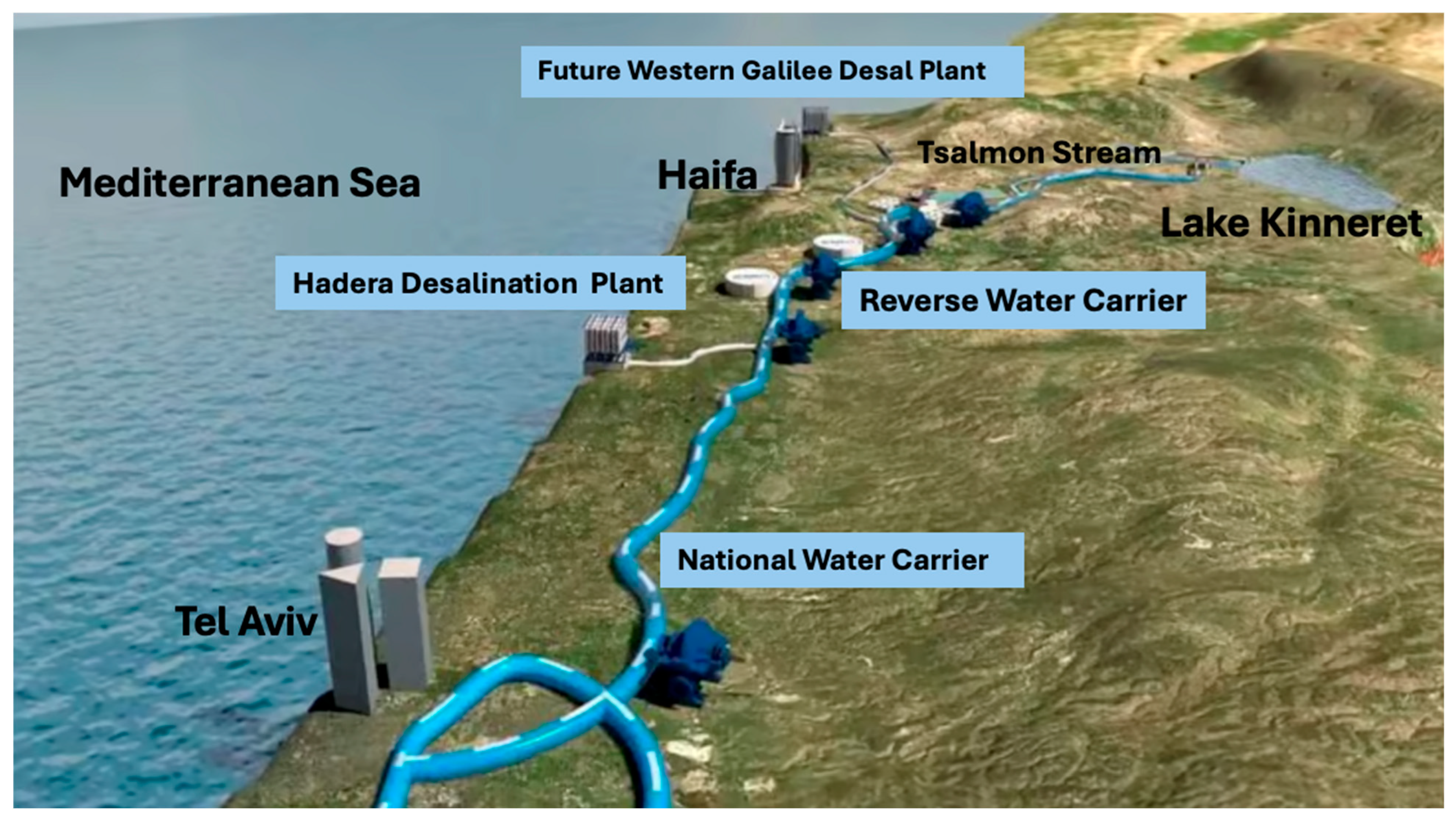

4. The Construction of a Reverse Water Carrier

“The reverse carrier was my idea originally. There were projections that climate change would lead to 3–4 years of consecutive droughts. I looked at our Lake Kinneret and realized that if we did not act, it could end up like Lake Chad or the Aral Sea. I said to myself: ‘the Kinneret is our national reservoir. Our population is growing. Desalination could be seriously disabled due to a military attack or to a pollution event. In such circumstances, the country’s emergency reservoir has to be the Kinneret. We need to leave its water level to be at a maximum. It’s not just security. The lake has historic and cultural significance, especially for Christianity. I used to joke: ‘If Jesus does come back, I need to ensure that he‘ll be able to cross the Kinneret.’ This seems to me to be a revolutionary idea. For the first time, desalination is not just for immediate domestic consumption but also for preserving natural ecosystems and for water security.”[84]

It was clear that I needed to get the government to expand the amount of desalinated water—and create an infrastructure that would allow us to recharge the Lake Kinneret so that we would never be in a position of having the water level fall below the black line. The question was: ‘how much?’ The government actually wanted to desalinate more water than I did—600 million cubic meters. Of course I would have liked to produce more water—200 million would have been ideal. But you have to remember: in a closed economic system, the associated investment would immediately be reflected in higher water prices. And I worried a lot about keeping water affordable for Israelis in lower economic strata. In the end we compromised on 300.”[91]

- Contribution to water security;

- Environmental Sustainability;

- Economic feasibility;

- Potential to improve regional stability and cooperation.

5. Evaluating the Reverse National Water Carrier

5.1. Water Security

5.2. Environmental Sustainability

“Ensuring adequate water supply to the upper basin could meet most of the agricultural demand and would enable releasing at least an equivalent amount to flow naturally downstream toward the lake. Such a move would:

Strengthen agriculture in the region and its stability;

Reduce competition over water resources between nature and agriculture;

Boost tourism in the “Land of Streams,” and

Most importantly, help preserve the unique aquatic ecosystems of the Kinneret Basin, ensure natural water flow from the basin to the lake and guarantee that natural water continues to enter the Kinneret to support its ecological stability.

Lakes do not exist in isolation from their surroundings—they are part of a lake–basin system: the watershed contributes water and nutrients to the lake, and in addition, there are a variety of biological and ecological interactions and processes between them.”[127]

“Dr. Barnea proposes to send water to the upper watershed instead of directly into the Kinneret—in effect, ceasing the use of natural water in the upper basin and replacing it with desalinated water from the national system. Aside from the logistical difficulties raised by the proposal, during drought years, when the national system likely cannot supply this water; and in wet years, when it would lead to the opening of the Degania Dam to release excess water, it also raises economic questions: Who will bear the enormous costs involved—over 4 shekels ($1.20) per cubic meter? Supplying such volumes of water would require the construction of an additional desalination plant. The proposal to fund this from outside the water economy is utterly unrealistic and instills false hope.”[128]

5.3. Lake Kinneret Water Quality

6. Economic Feasibility

7. Geopolitical Implications of Desalinized Water Storage in Lake Kinneret

8. Conclusions

- Climate adaptation and strengthening resilience requires moving beyond basin boundaries.

- 2.

- Desalination enables regional cooperation but exposes an element of economic risk.

- 3.

- Desalinated water strategies must anticipate systemic imbalances.

- 4.

- Desalination should change inter-basin rigidity but alone cannot guarantee resilience.

- 5.

- The Reverse Water Carrier and Israel’s willingness to transfer water across basins illustrates the potential of engineered resilience.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, P.; Wu, P.; Sheffield, J.; Otkin, J.A. A global transition to flash droughts under climate change. Science 2023, 380, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, Z.; Xie, H. Drought impacts on hydrology and water quality under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.C.; Mahat, V.; Ramirez, J.A. Adaptation to future water shortages in the United States caused by population growth and climate change. Earth’s Future 2019, 7, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fu, Z.; Liu, W. Impacts of precipitation variations on agricultural water scarcity under historical and future climate change. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gude, V.G. Desalination and water reuse to address global water scarcity. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2017, 16, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyl-Mazzega, M.A.; Cassignol, E. The Geopolitics of Seawater Desalination, 2012 Institut Francais des Relations Internationales. Available online: https://www.ifri.org/en/studies/geopolitics-seawater-desalination#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20there%20were%20more,and%20+12%25%20per%20year (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Yao, F.; Livneh, B.; Rajagopalan, B.; Wang, J.; Crétaux, J.F.; Wada, Y.; Berge-Nguyen, M. Satellites reveal widespread decline in global lake water storage. Science 2023, 380, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, C.; Hu, Y.; Shao, K.; Tang, X.; Zhang, L.; Gao, G.; Qin, B. Climate-induced salinization may lead to increased lake nitrogen retention. Water Res. 2023, 228, 119354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, M.; Beverley, J.D.; Bracegirdle, T.J.; Catto, J.; McCrystall, M.; Dittus, A.; Freychet, N.; Grist, J.; Hegerl, G.C.; Holland, P.R.; et al. Emerging signals of climate change from the equator to the poles: New insights into a warming world. Front. Sci. 2024, 2, 1340323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.R.; Meador, T.M. An assessment of the ecological impacts of inter-basin water transfers, and their threats to river basin integrity and conservation. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 1992, 2, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, L.; Dinar, A. Are intra-and inter-basin water transfers a sustainable policy intervention for addressing water scarcity? Water Secur. 2020, 9, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xin, Z.; Sun, S.; Zhang, C.; Fu, G. Assessing environmental, economic, and social impacts of inter-basin water transfer in China. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 130008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. Inter-basin water transfer and water security: A landscape sustainability science perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 390, 126326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tien Bui, D.; Talebpour Asl, D.; Ghanavati, E.; Al-Ansari, N.; Khezri, S.; Chapi, K.; Amini, A.; Thai Pham, B. Effects of Inter-Basin Water Transfer on Water Flow Condition of Destination Basin. Sustainability 2020, 12, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Kondolf, G.M. Environmental planning and the evolution of inter-basin water transfers in the United States. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1489917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, B.; Aldridge, D.C. Inter-basin water transfers and the expansion of aquatic invasive species. Water Res. 2018, 143, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Bai, T.; Liu, D.; Li, L. Impact of Climate Change on water diversion risk of Inter-basin Water Diversion Project. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 2731–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Li, L.; Mu, P.F.; Pan, B.Z.; Liu, J. Impact of climate change on water transfer scale of inter-basin water diversion project. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 2505–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU, Water Framework Directive, (2000/60/EC), the Date It Was Issued (23 October 2000), and the Official Journal Reference (OJ L 327, 22.12.2000, p. 1–73). Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/water/water-framework-directive_en (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Shiklomanov, I.A. Appraisal and assessment of world water resources. Water Int. 2000, 25, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Caldwell, P.V.; Sun, G.; McNulty, S.G.; Qin, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, N. Climate change challenges efficiency of inter-basin water transfers in alleviating water stress. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 044050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A. Seeking sustainability: Israel’s evolving water management strategy. Science 2006, 313, 1081–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A. Has Technology Trumped Adaptive Management? A Review of Israel’s Idiosyncratic Hydrological History. Glob. Environ. 2016, 9, 484–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Law, Amendment, 27, Israel Legislation Book 2604, p. 394, 13 February 2017. Available online: https://main.knesset.gov.il/activity/legislation/laws/pages/lawbill.aspx?t=lawreshumot&lawitemid=575299 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Fernandes, G. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal communication, 21 July 2025.

- Tal, A. To Make a Desert Bloom—The Israeli Agriculture Adventure and the Quest for Sustainability. Agric. Hist. 2007, 81, 228–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, E.; Berry, E.M.; Feitelson, E. Expert opinion survey on Israel’s food system: Implications for food and health policies. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2024, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, N. Water pricing in Israel: Various waters, various neighbors. In Water Pricing Experiences and Innovations; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Mordechay, E.; Abdeen, Z.; Robeen, S.; Schwartz, S.; Abdeen, A.M.; Mordehay, V.; Troen, A.M.; Chefetz, B.; Tal, A. Regional Water and Food Security Require Joint Israeli-Palestinian Guidelines for Wastewater Reuse and Food Safety. Food Nutr. Bull. 2024, 45, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOI Staff, Israel’s Population Tops 10 Million for 1st Time, on Eve of 77th Independence Day, Times of Israel, 29 April 2025. Available online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/israeli-population-tops-10-million-for-1st-time/#:~:text=In%20an%20annual%20report%20ahead,country%20was%20founded%20in%201948 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Kramer, I.; Tsairi, Y.; Roth, M.B.; Tal, A.; Mau, Y. Effects of population growth on Israel’s demand for desalinated water. Npj Clean Water 2022, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The Israeli Water Policy and Its Challenges During Times of Emergency. Water 2024, 16, 2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Some Estimates Calculate That the Figure Is Actually 80%. Roeh, A. Desalination in Israel: 80% of the Drinking Water Is No Longer Under State Control, Calcalist, 21 October 2021. Available online: https://www.calcalist.co.il/local_news/article/skhdgapbf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Tal, A. The implications of climate change driven depletion of Lake Kinneret water levels: The compelling case for climate change-triggered precipitation impact on Lake Kinneret’s low water levels. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 664, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmcke, C.; Schillo, R.S.; Tõnurist, P.; Thapa, R.; Torfing, J. Ten recommendations for political ecology case research. J. Political Ecol. 2022, 29, 694–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Environmental Health. How to Write a Case Study. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nceh (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Bardach, E.; Patashnik, E.M. A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving; CQ Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

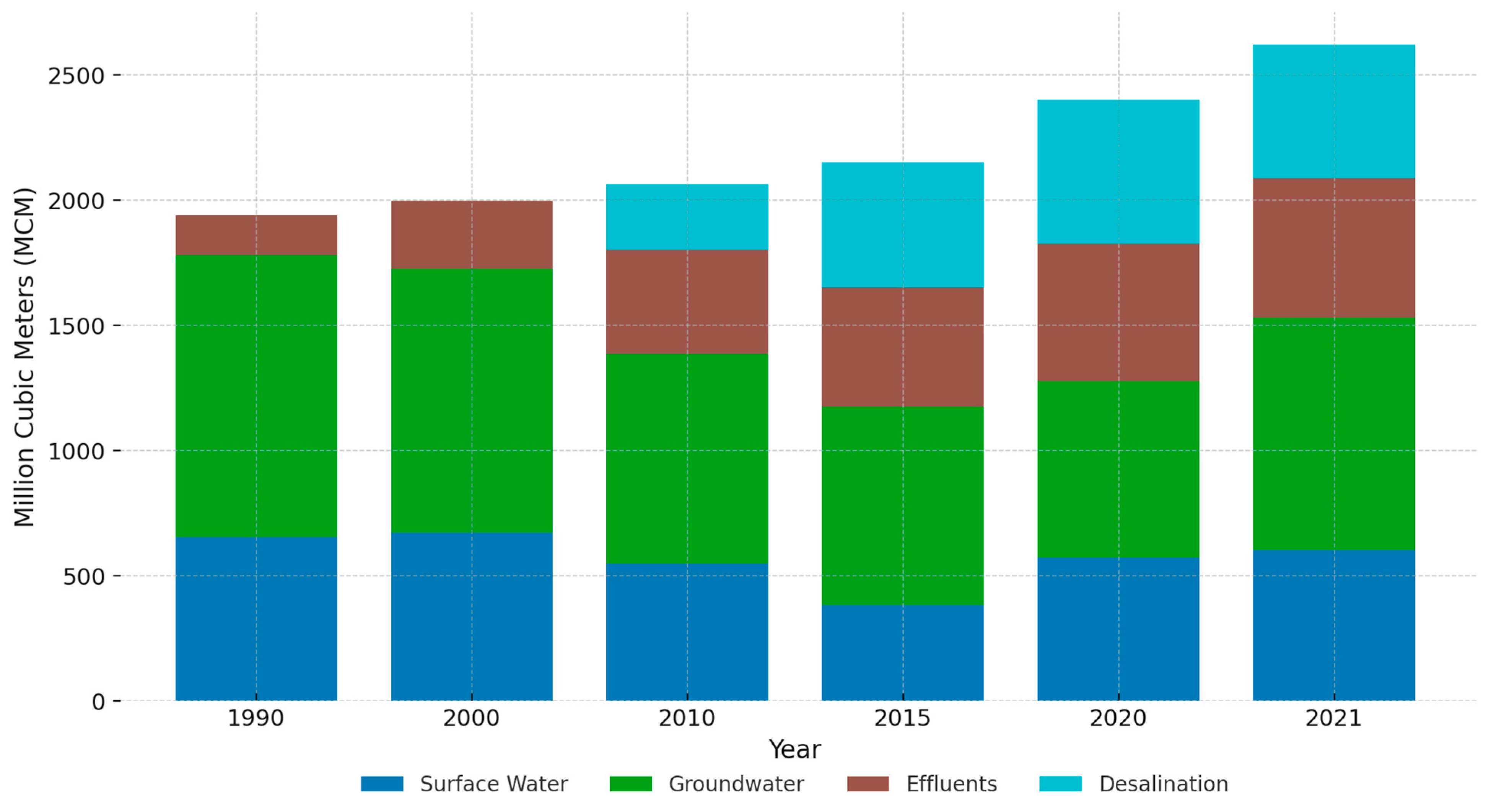

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Water and Waste Water, 2019. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/doclib/2019/23.shnatonwaterandsewage/diagrams23.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 2025, Israel Statistical Yearbook, 2025, Water and Wastewater. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/Pages/2025/%D7%9E%D7%99%D7%9D-%D7%95%D7%A9%D7%A4%D7%9B%D7%99%D7%9D-%D7%A9%D7%A0%D7%AA%D7%95%D7%9F-%D7%A1%D7%98%D7%98%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%98%D7%99-%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%A9%D7%A8%D7%90%D7%9C-2025-%D7%9E%D7%A1%D7%A4%D7%A8-76.aspx (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- OECD. Implementing the OECD Principles on Water Governance: Indicator Framework and Evolving Practices; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Water. Water Security and the Global Water Agenda (Analytical Brief); United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shafee, F.A.; Shafiq, N.; Farhan, S.A.; Adebanjo, A.; Abd Razak, S.N.; Kumar, V. Sustainable Lake Management Framework for Performance Monitoring and Quality Assessment. Migr. Lett. 2024, 21, 771–783. [Google Scholar]

- Hajkowicz, S.; Collins, K. A review of multiple criteria analysis for water resource planning and management. Water Resour. Manag. 2007, 21, 1553–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meadowcroft, J. What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long-term energy transitions. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A. A Charismatic Hyena: Insights for Human-Wildlife Interaction in Shared Urban Environments. Case Stud. Environ. 2024, 8, 2302549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Gurion, D. Testimony Before United Nations Special Committee on Palestine, Report of the General Assembly, 4 July 1947. Available online: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-182033/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ben Gurion, D. Southbound. In Studies in the Bible; Am Oved: Tel Aviv, Israel, 1969; pp. 132–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ziv, B.; Saaroni, H.; Pargament, R.; Harpaz, T.; Alpert, P. Trends in rainfall regime over Israel, 1975–2010, and their relationship to large-scale variability. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 1751–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Ben-Gurion, Southbound (1956) Reprinted in the Original Hebrew in the Ben Yehuda Project Website. Available online: https://benyehuda.org/read/36026 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Menahem, G. Policy paradigms, policy networks and water policy in Israel. J. Public Policy 1998, 18, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N. Israel’s national water carrier. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 2, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Galnoor, I. Water Policy Making in Israel’. Policy Anal. 1978, 4, 339–367. [Google Scholar]

- Galnorr, I. Water Policy Making in Israel. In Water Quality Management Under Conditions of Scarcity, Israel as a Case Study; Shuval, H., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- Orni, E.; Efrat, E. Geography of Israel; Israel Universities Press: Jerusalem, Israel, 1971; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, A. Israeli Agriculture—Innovation and Advancement. In Food Scarcity Surplus; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidar, O. Israel: From Water Scarcity to Water Surplus. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Israel; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, A. The Land is Full, Addressing Overpopulation in Israel; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2016; pp. 46–78. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D. Policies for water demand management in Israel. In Water Policy in Israel: Context, Issues and Options; Springer: Dordrecht, The, Netherlands, 2013; pp. 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Portnov, B.A.; Meir, I. Urban water consumption in Israel: Convergence or divergence? Environ. Sci. Policy 2008, 11, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A. The Environment in Israel, Natural Resources, Crises, Campaigns and Policy, From the Advent of Zionism Until the 21st Century; Kibbutz HaMeuchad Press: Bnei Brak, Israel, 2006; pp. 290–340. [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer, A.; Givati, A.; Zohary, T. Hydrology. In Lake Kinneret: Ecology and Management; Sukenik, A., Berman, T., Nishri, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, A. Rethinking the sustainability of Israel’s irrigation practices in the Drylands. Water Res. 2016, 90, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel State Comptroller. Report on Water Management in Israel; Israel State Comptroller: Jerusalem, Israel, 1990; pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Plant, S. Water Policy in Israel. Policy Stud. 2000, 47, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, D.; Golan, G. Ashkelon Desalination Plant Begins Operations. Globes, 7 August 2005. Available online: https://en.globes.co.il/en/article-942504 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Tal, A. The desalination debate—Lessons learned thus far. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2011, 53, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, S.M. Let There be Water: Israel’s Solution for a Water-Starved World; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Government Decision 4895, 7 March 1999. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/pages/07mar19994895 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Fietelson, E. The four Eras of Israeli water policy. In Water Policy in Israel: Context, Issues and Options; Becker, N., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Naor, M. The Founding of Mekorot, Mekorot Website (Last Visited, 18 June 2025). Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210625060238/https://wold.mekorot.co.il/Eng/newsite/InformationCenter/Milestones/Pages/Founders.aspx (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Teschner, N.; Negev, M. The Development of Water Infrastructures in Israel: Past, Present and Future. Shared Borders, Shared Waters: Israeli-Palestinian and Colorado River Basin Water Challenges; CRC Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dreizin, Y.; Tenne, A.; Hoffman, D. Integrating large scale seawater desalination plants within Israel’s water supply system. Desalination 2008, 220, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teff-Seker, Y.; Eiran, E.; Rubin, A. Israel turns to the sea. Middle East J. 2018, 2, 610–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A. The Desalination Debate–Lessons Learned Thus Far. Environment 2011, 53, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A. Addressing Desalination’s Carbon Footprint: The Israeli Experience. Water 2018, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Gal, A.; Tal, A.; Tel-Zur, N. The sustainability of arid agriculture: Trends and challenges. Ann. Arid Zone 2021, 45, 227–258. [Google Scholar]

- Feitelson, E.; Rosenthal, G. Desalination, space and power: The ramifications of Israel’s changing water geography. Geoforum 2012, 43, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. Undermining demand management with supply management: Moral hazard in Israeli water policies. Water 2016, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinitz, Y. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal interview, 10 August 2025.

- OECD. Israel: Agriculture and Water Policies-Main Characteristics and Evolution from 2009 to 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/topics/policy-sub-issues/water-and-agriculture/oecd-water-policies-country-note-israel.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Chenoweth, J.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Bruggeman, A.; Lelieveld, J.; Levin, Z.; Lange, M.A.; Xoplaki, E.; Hadjikakou, M. Impact of climate change on the water resources of the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East region: Modeled 21st century changes and implications. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, W06506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udasin, S. Lake Kinneret Experiences Worst May Since 1920, Jerusalem Post. 5 June 2017. Available online: https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/lake-kinneret-experiences-worst-may-since-1920-494791?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Tal, A. Climate change’s impact on Lake Kinneret: Letting the data tell the story. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 1272–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaide, M. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal interview, 26 June 2025.

- Bar-Eli, A. Desalinated Water Is Flowing in the National Water Carrier, The Desalination Facility in Hadera has Begun Running, The Marker, 23 December 2009. Available online: https://www.themarker.com/misc/2009-12-23/ty-article/0000017f-dbf7-d856-a37f-fff7524a0000 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Shaham, G. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal communication, 18 June 2025.

- Shaham, G. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal communication, 6 August 2025.

- Government Decision 3866, 10 June 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/pages/dec3866_2018 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Government Decision 4514, 24 February 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/pages/dec4514_2019 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Yaacoby, Y. (Mekorot, Tel Aviv, Israel). Personal communication, 3 July 2025.

- Mekorot. For the First Time in Israel–Mekorot Will Carry Desalinated Seawater from the Mediterranean to the Kinneret, 1 January 2025. Available online: https://www.globalwaterintel.com/articles/for-the-first-time-in-israel-mekorot-will-carry-desalinated-seawater-from-the-mediterranean-to-the-kinneret-mekorot (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Keshet, N. (Nature and Parks Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal interview, 24 June 2025.

- Rinat, Z. National Water Project Faces Changes: Inside the Efforts to Refill Israel’s Dwindling Lake Kinneret, Haaretz, 24 February 2020. Available online: https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2020-02-24/ty-article-magazine/.premium/inside-the-efforts-to-refill-israels-dwindling-lake-kinneret/0000017f-e396-d568-ad7f-f3ff115b0000 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Bakker, K. Water security: Research challenges and opportunities. Science 2012, 337, 914–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritzalis, D.; Theocharidou, M.; Stergiopoulos, G. Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 978–983. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, W.; Merabti, M.; Fergus, P. A survey of critical infrastructure security. In International Conference on Critical Infrastructure Protection; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston, P.; Smith, T.; White, I.; Elrick-Barr, C. Adapting critical infrastructure to climate change: A scoping review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 135, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixler, A.; Montgomery, M.; Lane, R. Military Mobility Depends on Secure Critical Infrastructure. 2025. Available online: https://ismg-cdn.nyc3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/asset_files/external/fdd-csc20reportmilitarymobility.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Blass, S. Water in Strife and Action; Masada: Givataim, Israel, 1973; p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, A. The evolution of Israeli water management: The elusive search for environmental security. In Water Security in the Middle East; Cahan, J., Ed.; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Israel Water Authority, General Background on Water Desalination. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/pages/project-water-desalination-background (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Hassan Nasrallah, Secretary General of Hezboolah, Televised Interview, 12 July 2019, Uploaded by Alma Research and Education Website. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Przcf2SGwV0 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Gross, J.A. After Alleged Iranian Cyberattack, Israel’s Water Authority Beefs up Defenses, Times of Israel, 21 July 2021. Available online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/after-alleged-iranian-cyberattack-israels-water-authority-beefs-up-defenses/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Alexandra Lukash, A.; Somfalvi, A. Steinitz: The National Carrier Will Carry Water to the Kinneret from the Desalination Facilities, Ynet, 30 August 2018. Available online: https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5337864,00.html (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Yaacoby, Y. (Mekorot, Tel Aviv, Israel). Personal communication, 24 July 2025.

- Surkes, S. Water Authority Says Israel Experiencing Driest Winter in a Century, Times of Israel 2 February 2025. Available online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/water-authority-says-israel-experiencing-driest-winter-in-a-century/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Elsaid, K.; Kamil, M.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Wilberforce, T.; Olabi, A. Environmental impact of desalination technologies: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, N.; Gertner, Y.; Shoham-Frider, E. Seawater quality at the brine discharge site from two mega size seawater reverse osmosis desalination plants in Israel (Eastern Mediterranean). Water Res. 2020, 171, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermiyahu, U.; Tal, A.; Ben-Gal, A.; Bar-Tal, A.; Tarchisky, J.; Lahav, O. Rethinking Desalinated Water Quality and Agriculture. Science 2007, 318, 920–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, A.; Tal, A.; Becker, N.; El-Khateeb, N.; Asaf, L.; Assi, A.; Adar, E. Stream restoration as a basis for Israeli–Palestinian cooperation: A comparative analysis of two transboundary streams. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2010, 8, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Katz, D. Basin management under conditions of scarcity: The transformation of the Jordan River basin from regional water supplier to regional water importer. Water 2022, 14, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnik, Y.; Lerner, Y. Middle Tzalmon Stream and Tzalmon Ruins–Recommended Hiking Trail in Tzalmon Stream National Park, Nature and National Parks Authority Website, 2019. Available online: https://www.parks.org.il/trip/tzalmon-creek/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Dolev, A. (Nature and Parks Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal interview, 24 June 2025.

- Tsoar, A. (Nature and Parks Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal interview, 24 June 2025.

- Tal, A. Natural Heritage: Leisure Services in Israel’s National Parks, Forests, and Nature Reserves. In Israeli Life and Leisure in the 21st Century; Sagmore-Venture Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rabineau, S. Walking the land: A History of Israeli Hiking Trails; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, Indiana, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zaide, M. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal communication, 15 October 2025.

- Hambright, K.D.; Zohary, T. Lakes Hula and Agmon: Destruction and creation of wetland ecosystems in northern Israel. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 1998, 6, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzan, A. Wetlands of Israel, Wetlands of Tropical and Subtropical Asia and Africa: Biodiversity, Livelihoods and Conservation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Givati, A.; Tal, A. The hydrological situation in the Kinneret basin–Observed trends and projections based on hydro-climatic models. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 8, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Litaor, M.I.; Badihi, N.; Amouyal, A.; Reichman, O. The influence of irrigation with Lake Kinneret water on the chemistry of soils in the headwater basin. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2025, 89, e70087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, I. Is It Right to Disconnect the Kinneret from Its Watershed? Ecology and Environment, 2021. Available online: https://magazine.isees.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/EE_autumn2021_pages-70-71.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Shaham, G. Response: The Changes in the Role of the Kinneret in Israel’s Water Economy. Ecology and Environment, 202112. Available online: https://magazine.isees.org.il/?p=36520 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Israel Water Authority Planning Department. Master Plan for the Upper Kinneret Basin–Expanding Supply of Water to the Upper Kinneret, August, 2025, (Hebrew Powerpoint Presentation Available from Author); Israel Water Authority Planning Department: Jerusalem, Israel, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, I. Our Natural Water Resources Are Not Infinite-It’s Time to Make Bold Decisions, Kalkalist, 20 March 2025. Available online: https://www.calcalist.co.il/local_news/article/sycrstt31e (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- See for Example: Matthew 4–9; Mark 1, 4 and 6; Luke 5, 8–9 and John 6:1–25, New Testament. Available online: https://www.catholic.org/bible/new_testament.php (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Barnea, I. Environmental Aspects of the Issue Connecting the Upper Kinneret Region to the National Water System during an Era of Climate Change. Water Eng. Isr. Water Mag. 2021, 130, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, A. Pollution in a Promised Land, An Environmental History of Israel; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 213–214. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed., Incorporating the 1st Addendum, 24 April 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549950 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Nishri, A.; Stiller, M.; Rimmer, A.; Geifman, Y.; Krom, M. Lake Kinneret (The Sea of Galilee): The effects of diversion of external salinity sources and the probable chemical composition of the internal salinity sources. Chem. Geol. 1999, 158, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, G.; Ronen, D.; Stiller, M.; Nishri, A. Cl/Br ratios of Lake Kinneret, pore water and associated springs. J. Hydrol. 1999, 225, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, A.; Hurwitz, S.; Gvirtzman, H. Spatial and temporal characteristics of saline springs: Sea of Galilee, Israel. GroundWater 1999, 37, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudy, J. Back to Basics: Lake Residence Time, How Fresh Is Your Fresh Water? International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2021. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/ela/blog/lake-residence-time-how-fresh-is-your-fresh-water/#:~:text=Lake%20residence%20time%20is%20calculated,differ%20from%20lake%20to%20lake (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ambrosetti, W.; Barbanti, L.; Sala, N. Residence time and physical processes in lakes. J. Limnol. 2003, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, A. Eutrophication and water quality of lakes: Control by water residence time and transport to sediments. Hydrol. Sci. J. 1974, 19, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Li, J.; Qi, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Lin, Y. Impacts of water residence time on nitrogen budget of lakes and reservoirs. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, F.; Mackay, E.B.; Barker, P.; Davies, S.; Hall, R.; Spears, B.; Exley, G.; Thackeray, S.J.; Jones, I.D. Can reductions in water residence time be used to disrupt seasonal stratification and control internal loading in a eutrophic monomictic lake? J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, P.J. The phosphorus budget of Cameron Lake, Ontario: The importance of flushing rate to the degree of eutrophy of lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1975, 20, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, T.; Read, L. Lake Washington Area Regional Background Data Evaluation and Summary Report 2017, Washington State Department of Ecology. Available online: https://apps.ecology.wa.gov/publications/documents/1609064.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Quinn, F.H. Hydraulic residence times for the Laurentian Great Lakes. J. Great Lakes Res. 1992, 18, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, S.; Pokorný, J.; Hauserm, V. Restoration of lakes through sediment removal, with case studies from lakes Trummen, Sweden and Vajgar, Czech Republic. In Restoration of Lakes, Streams, Floodplains, and Bogs in Europe: Principles and Case Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Shaham, G. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal interview, 29 June 2025.

- Kolodny, Y.; Katz, A.; Starinsky, A.; Moise, T.; Simon, E. Chemical tracing of salinity sources in Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee), Israel. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1999, 44, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirlas, V.; Anker, Y.; Aizenkod, A.; Goldshleger, N. Irrigation quality and management determine salinization in Israeli olive orchards. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 129–15143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveh, E.; Ben-Gal, A. Irrigation with water containing salts: Evidence from a macro-data national case study in Israel. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 170, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvirtzman, H. Water Resources of Israel, 2nd ed.; Yad Ben Tzvi: Jerusalem, Israel, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hadas, O.; Kaplan, A.; Sukenik, A. Long-term changes in cyanobacteria populations in Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee), Israel: An eco-physiological outlook. Life 2015, 5, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q. The impact of cyanobacteria blooms on the aquatic environment and human health. Toxins 2022, 14, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinneret Limnological Laboratory. Available online: https://www.ocean.org.il/kinneret-limnological-laboratory-center/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Israel Oceanic and Limnological Research, Assessment of the Implications of Two Alternatives for Connecting Disconnected Areas to Lake Kinneret, (Hebrew) February, 2020. (Copy with Author).

- Gal, G. (Kinneret Limnological Institute, Migdal, Israel). Personal communication, 24 June 2025.

- Letter from Eran Friedlander and Gilboa, The Technion, Israel Institute of Technology to Firas Talhami, Israel Water Authority, Average Age of Water in the Kinneret and Different Future Scenarios, 2 February 2020 (copy with author).

- Gilboa, Y.; Friedler, E.; Talhami, F.; Gal, G. A novel approach for accurate quantification of lake residence time—Lake Kinneret as a case study. Water Res. X 2022, 16, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaide, M. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal communication, 6 July 2025.

- Marin, P.; Tal, S.; Yeres, J.; Ringskog, K. Water Management in Israel Key Innovations and Lessons Learned for Water-Scarce Countries, World Bank, August 2017. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/657531504204943236/pdf/Water-management-in-Israel-key-innovations-and-lessons-learned-for-water-scarce-countries.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Israel Water Authority, Water and Sewage Prices for Household Consumers in Municipal Water and Sewage Companies. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/pages/rates_general1 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Venger, D.; Halfon, N.; Yosef, H. Historical Trends and Future Projected Trends in Rainfall Patterns Israel by the End of This Century, Israel Metereological Service: Jerusalem, 2022. Available online: https://ims.gov.il/he/node/228 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Salomons, E.; Housh, M.; Katz, D.; Sela, L. Water-energy nexus in a desalination-based water sector: The impact of electricity load shedding programs. npj Clean Water 2023, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, N. Can desalination save a drying world? Energy Monitor, 17 January 2023. Available online: https://www.energymonitor.ai/tech/can-desalination-save-a-drying-world/?utm_source=chatgpt.com&cf-view (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ellickson, B.; Penalva-Zuasti, J. Intertemporal insurance. J. Risk Insur. 1997, 64, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, A. Food security in Israel: Challenges and policies. Foods 2024, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the UN, State of Israel, Fisheries, Data, 2007. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/docs/DOCUMENT/fcp/en/FI_CP_IL.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Gophenm, M. Fishery management in Lake Kinneret: A review. J. Fish. Aquac. Dev. 2018, 2, 2577. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, S. The Ministry of Interior is Checking the State of the Kinneret Beaches Where Bathing is Banned Again, Haaretz, 16 May 2001. Available online: https://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/2001-05-16/ty-article/0000017f-df85-df9c-a17f-ff9d54380000 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Fleischer, A.; Gindin, Y.; Tsur, Y. Integrating recreational ecosystem service valuations into Israel’s Water Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 227, 108391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel Electricity Prices, Global Petrol Prices, Website. Available online: https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/Israel/electricity_prices/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Fernandes, G. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal interview, 15 July 2025.

- Sharon, Y. Israel’s Energy Prices are the Highest They’ve been in Nine Years, Jerusalem Post, 26 January 2023. Available online: https://www.jpost.com/business-and-innovation/energy-and-infrastructure/article-729757 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection, Carbon Pricing in Israel, 29 June 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/pages/carbon_pricing_in_israel/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Fathallah, R.M. Water disputes in the Middle East: An international law analysis of the Israel-Jordan Peace Accord. J. Land Use Environ. Law 1996, 12, 119–151. [Google Scholar]

- Peace Treaty Between the State of Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Annex II, “Water Related Matters,” 26 October 1994. Available online: https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/default/files/document/files/2024/05/il20jo941026peacetreatyisraeljordan.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Jordan Department of Statistics. Population Projections for the Kingdom’s Residents during the Period 2015–2050, 2016, Amman, Jordan. Available online: https://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/DataBank/Population/Population_Estimares/POP_PROJECTIONS(2015-2050).pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- UNICEF, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, Access to Safe Water and Sanitation for Every Child, 2025. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/jordan/water-sanitation-and-hygiene# (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Tal, A. The Environmental Impacts of Overpopulation. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel Formally Agrees to Double Water Supply to Jordan, The Arab Weekly, 12 October 2021. Available online: https://thearabweekly.com/israel-formally-agrees-double-water-supply-jordan (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Cohen, G.; Winter, O.; Shani, G. Thirty Years of the Peace Agreement with Jordan: Time to Upgrade Water Cooperation, INSS Insight No. 1908, 31 October 2024. Available online: https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/No.-1908.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Al-Addous, M.; Bdour, M.; Alnaief, M.; Rabaiah, S.; Schweimanns, N. Water Resources in Jordan: A Review of Current Challenges and Future Opportunities. Water 2023, 5, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowitz, D.; Margheri, M.; Yakhoul, H.; Bensabat, J.; Rusteberg, B.; Yüce, S. Contribution to implementing a fair water and energy exchange between Israel and Jordan. In Water Resources Management and Sustainability: Solutions for Arid Regions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, A.; Roth, M.B. Reenergizing Peace: The Potential of Cooperative Energy to Produce a Sustainable and Peaceful Middle East. Energy Law J. 2020, 41, 167–209. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G. (Israel Water Authority, Jerusalem, Israel). Personal communication, 16 October 2025.

- World Government Bonds, Jordan Credit Rating. Available online: https://www.worldgovernmentbonds.com/credit-rating/jordan/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Barnea, I. (Society for Protection of Nature in Israel, Tel Aviv, Israel). Personal interview, 2 July 2025.

- The Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement-Annex III, Article 40, “Water”, 28 September 1995. Available online: https://www.gov.il/en/pages/the-israeli-palestinian-interim-agreement-annex-iii (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- PWA (Palestinian Water Authority). 2014. Decree Law No. 14 of 2014 Relating to the Water Law. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/fr/c/LEX-FAOC147322/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Perrier, J. Palestinian Water Laws: Between Centralization, Decentralization, and Rivalries, Agence Française de Développement. Available online: https://www.pseau.org/outils/ouvrages/afd_palestinian_water_laws_between_centralization_decentralization_and_rivalries_2020.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection. The Main Water Resources in Israel, 27 March 2024, Ministry of Environmental Protection Website. Available online: https://www.gov.il/en/pages/main_water_resources_in_israel (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Jayousi, A. The Oslo II Accords in Retrospect: Implementation of the Water Provisions in the Israeli and Palestinian Interim Peace Agreement. In Water Wisdom: Preparing the Groundwork for Cooperative and Sustainable Water Management in the Middle East; Tal, A., Rabbo, A.A., Eds.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kerret, D. Article 40, An Israeli Retrospective. In Water Wisdom: Preparing the Groundwork for Cooperative and Sustainable Water Management in the Middle East; Tal, A., Rabbo, A.A., Eds.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan, M.; Abu-Awwad, A.; Abu-Madi, M. Willingness of farmers to use treated wastewater for irrigation in the West Bank, Palestine. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2022, 38, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, H.B. Water Scarcity and the Israeli Occupation: How Territorial Fragmentation is Worsening Water Stress in Palestine, Fanack: Water of the Middle East and North Africa, 14 March 2025. Available online: https://water.fanack.com/publications/water-scarcity-and-the-israeli-occupation-how-territorial-fragmentation-is-worsening-water-stress-in-palestine/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Sarsour, A.; Nagabhatla, N. Options and strategies for planning water and climate security in the occupied Palestinian territories. Water 2022, 14, 3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoub, E. Water Resources Management Crisis in Palestine. In Environmental Consequences of International Conflicts. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Semenov, A.V., Zonn, I.S., Kostianoy, A.G., Zhiltsov, S.S., Negm, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obidallah, M.T. Water and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Cent. Eur. J. Int. Secur. Stud. 2008, 129, 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, A. Thirsting for Pragmatism: A Constructive Alternative to Amnesty International’s Report on Palestinian Access to Water. Isr. J. Foreign Aff. 2015, 4, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitelson, E. Implications of shifts in the Israeli water discourse for Israeli-Palestinian water negotiations. Political Geogr. 2002, 21, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.T. Water Wars and Water Reality: Conflict and Cooperation Along International Waterways, In Environmental Change, Adaptation, and Security; Lonergan, S.C., Ed.; 1999 NATO ASI Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, N. The Slowing Down of Israel-Arab Relations Under the Netanyahu Government Nimrod Goren, Middle East Institute, Policy Brief, May 2023. Available online: https://www.mei.edu/publications/slowing-down-israel-arab-relations-under-netanyahu-government (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Times of Israel Staff, Bennett Met Secretly Last Week with Jordan’s King Abdullah in Amman, Times of Israel 8 July 2021. Available online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/bennett-met-secretly-with-jordans-king-abdullah-in-amman-reports/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Declaration of Intent Between the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, The State of Israel, and the United Arab Emirates, 8 November 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.il/en/pages/press_081122 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Israel Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, UAE, Jordan and Israel Ate to Mitigate Climate Change with Sustainability Project, 22 November 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.il/en/pages/press_221121 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Nada Majdalani, Director, Ecopeace Palestine, Presentation at UN Security Council, May 2019. Available online: https://time.com/5927349/heirs-of-the-arab-spring/?utm (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Riedel, B.; Sachs, N. Israel, Jordan, and the UAE’s Energy Deal Is Good News, Brookings, 23 November 2021. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/israel-jordan-and-the-uaes-energy-deal-is-good-new (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Hechtman, J. A Firm Handshake: States, Corporations, and Diplomacy in the Levant. 2025. Available online: https://purl.stanford.edu/vm164vw6484/version/2 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Mahmoud, M. The Looming Climate and Water Crisis in the Middle East and North Africa. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 19 April 2024. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/04/the-looming-climate-and-water-crisis-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa?lang=en&utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Declaration of Intent Between the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, the State of Israel and the United Arab Emirates, 22 November 2021. Available online: https://www.mwi.gov.jo/EBV4.0/Root_Storage/AR/EB_Ticker/%D9%88%D8%AB%D9%8A%D9%82%D8%A9_%D8%A7%D8%B9%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86_%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D9%88%D8%A7%D261l9%8A%D8%A7.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ratka, E.; Rimmel, M. Israeli-Jordanian Water Management Relations, Konrad Adenauer Siftung–International Reports, 14 April 2025. Available online: https://www.kas.de/en/web/auslandsinformationen/artikel/detail/-/content/israeli-jordanian-water-management-relations (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Surkes, S. In World First, Israel Begins Pumping Desalinated Water into Depleted Sea of Galilee, Times of Israel, 11 November 2025. Available online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/in-world-first-israel-begins-pumping-desalinated-water-into-depleted-sea-of-galilee (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Miao, Q.; Liu, X.; Shi, H.; Wei, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gonçalves, J.M.; Feng, W. Lake-area shrinkage driven by the combined effects of climate change and human activities. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 175, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Cook, K.H.; Vizy, E.K. How shrinkage of Lake Chad affects the local climate. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 61, 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, X.; Chang, C.; Liu, T.; Huang, Y.; Zan, C.; Ma, X.; De Maeyer, P.; Van de Voorde, T. Impacts of climate change and evapotranspiration on shrinkage of Aral Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, T.P.; Pierce, D.W. When will Lake Mead go dry? Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W03201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Lakes, T.; Omarzadeh, D.; Pourmoradian, S. Health effects of shrinking hyper-saline lakes: Spatiotemporal modeling of the Lake Urmia drought on the local population, case study of the Shabestar County. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Livneh, B.; Rajagopalan, B. Earth’s large lakes are shrinking. TheScienceBreaker 2023, 9. Available online: https://www.thesciencebreaker.org/breaks/earth-space/earths-large-lakes-are-shrinking (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zubieta, R.; Molina-Carpio, J.; Laqui, W.; Sulca, J.; Ilbay, M. Comparative analysis of climate change impacts on meteorological, hydrological, and agricultural droughts in the lake Titicaca basin. Water 2021, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. Desalination and Circularity: How Catalonia Is Planning to Solve Its Water Crisis Without Rain, EuroNews, 2 September 2024. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/green/2024/09/02/desalination-and-circularity-how-catalonia-is-planning-to-solve-its-water-crisis-without-r#:~:text=Catalonia’s%20drought%20emergency,worst%20drought%20in%20modern%20history (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Mugabi, J.; Kennedy-Walker, R. How Zambia’s Inefficient Commercial Water Utilities Are Slowing Down Progress in Service Coverage and What to Do About It, World Bank Blogs, 16 February 2022. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/water/how-zambias-inefficient-commercial-water-utilities-are-slowing-down-progress-service-coverage (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Mwiikisa, M.K.; Mubanga, K.H. In the Trenches in the Fight Against Drought, National Adaptation Plans, Global Network, 2024. Available online: https://napglobalnetwork.org/stories/zambia-trenches-fight-against-drought/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Maluleke, L. Water Water Everywhere, But Zambia Is Water Insecure, 21 June 2024, Good Governance for Africa. Available online: https://gga.org/water-water-everywhere-but-zambia-is-water-insecure/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

| Facility Location | Annual Water Output (MCM) | Start of Water Supply |

|---|---|---|

| Ashkelon | 117.7 | August 2005 |

| Palmahim | 90 | May 2007–August 2013 |

| Hadera | 137 | December 2009 |

| Sorek | 150 | November 2013 |

| Ashdod | 100 | October 2015 |

| Present Total Output (2025) | 594.7 | |

| Additional Anticipated Desalination Production | ||

| Sorek B | 200 | January 2026 |

| Western Galilee | 100 | January 2028 |

| Hefer Valley | 200 | January 2033 (rough estimate) |

| Future Output (2033) | 500 | |

| Pipe diameter | 64 inches |

| Total pumping capacity | 15,000 m3/h |

| Hydraulic loss | 3 m/km |

| Elevation lifts: | 0–140 m; 140 m–170 m (Total: 170 m) |

| Marginal Transport Cost | ~$0.5/m3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tal, A. Thinking Outside the Basin: Evaluating Israel’s Desalinated Climate Resilience Strategy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310636

Tal A. Thinking Outside the Basin: Evaluating Israel’s Desalinated Climate Resilience Strategy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310636

Chicago/Turabian StyleTal, Alon. 2025. "Thinking Outside the Basin: Evaluating Israel’s Desalinated Climate Resilience Strategy" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310636

APA StyleTal, A. (2025). Thinking Outside the Basin: Evaluating Israel’s Desalinated Climate Resilience Strategy. Sustainability, 17(23), 10636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310636