Managing Food Leftovers in Polish Households in Terms of the Food Waste Hierarchy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

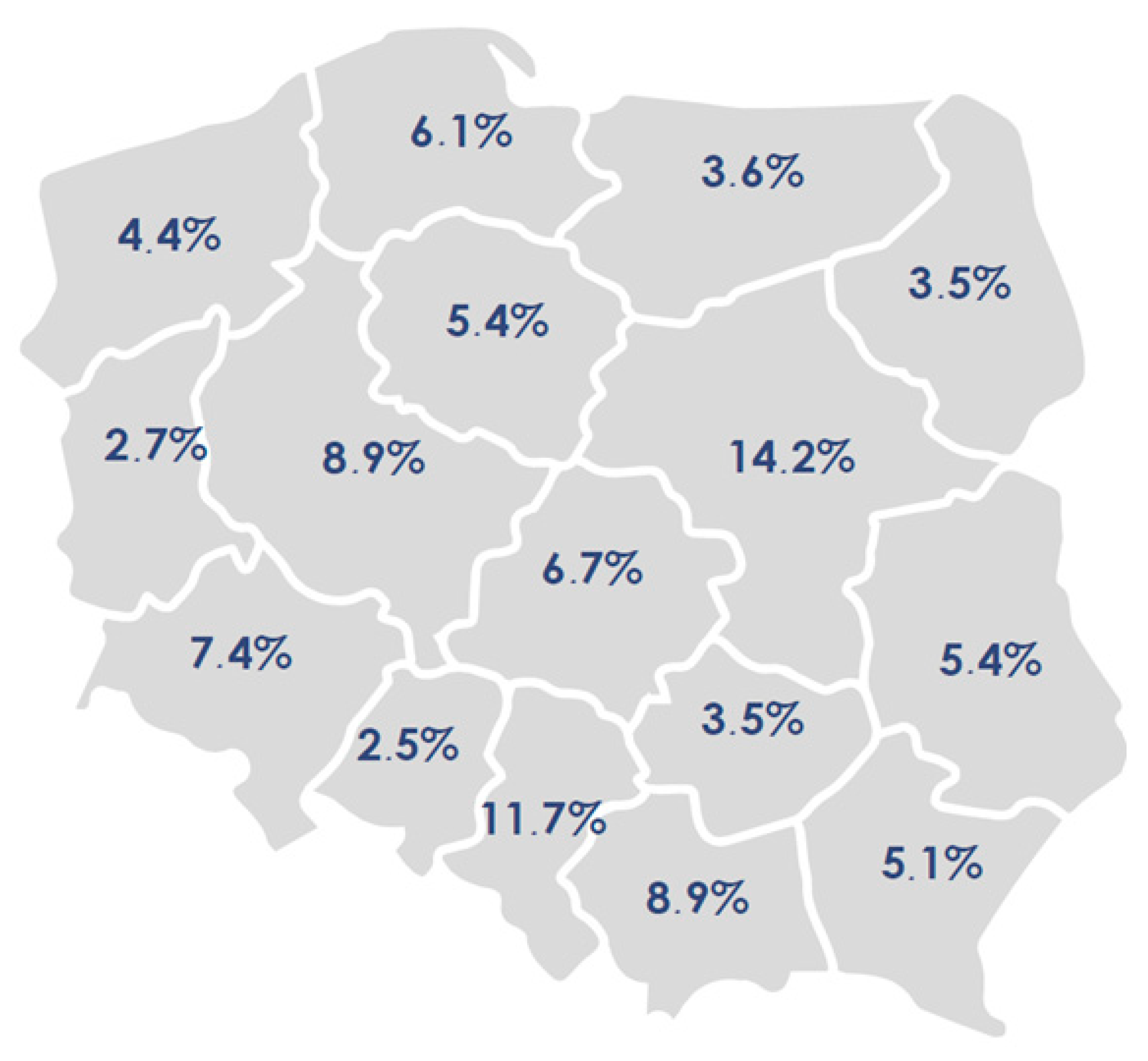

2.1. Data Collection and Questionnaire

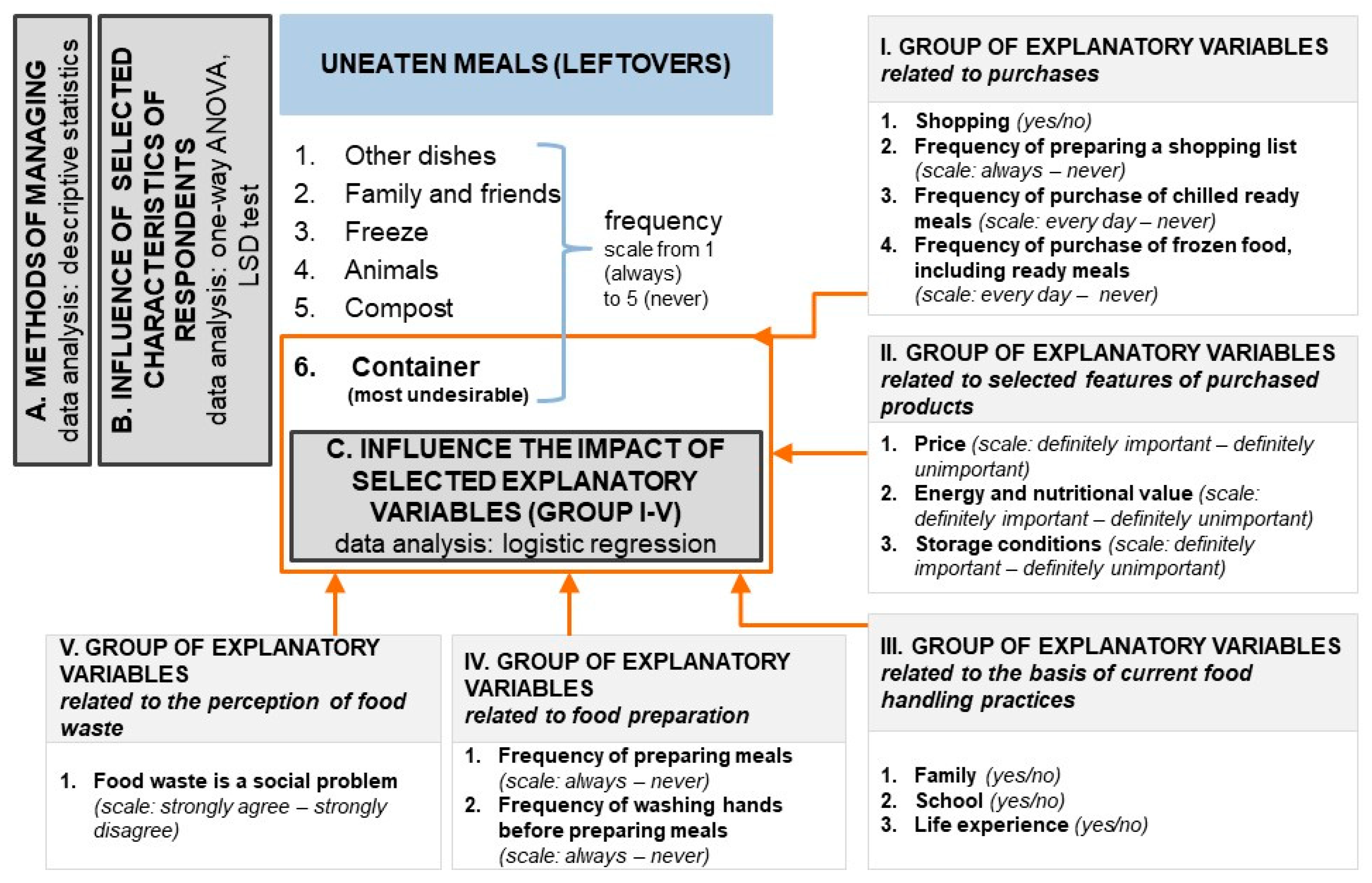

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Methods of Managing Food Leftovers in Polish Households

3.2. The Influence of Selected Respondent and Household Characteristics on Food Leftover Management Practices

3.3. Characteristics of Explanatory Variables and Their Impact on the Practice of Throwing Away Food Leftovers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2024. Think Eat Save Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/45275/Food-Waste-Index-2024-key-messages.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Bilska, B.; Tomaszewska, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Food waste in polish households—Characteristics and sociodemographic determinants on the phenomenon. Nationwide research. Waste Manag. 2024, 176, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Gimenez, A.; Ares, G. Household food waste in an emerging country and the reasons why: Consumer’s own accounts and how it differs for target groups. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.M.; Hartikainen, H.; Heikkila, L.; Reinikainen, A. Food waste volume and composition in Finnish households. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Otterbring, T.; Löfgren, M.; Gustafsson, A. Reasons for household food waste with special attention to packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.; Kerr, G.; Pearson, D.; Mirosa, M. The attributes of leftovers and higher-order personal values. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1965–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Walton, K. Plate waste in hospitals and strategies for change. e-SPEN Eur. e-J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 6, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eičaitė, O.; Baležentis, T. Disentangling the sources and scale of food waste in households: A diary-based analysis in Lithuania. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasza, G.; Dorkó, A.; Kunszabó, A.; Szakos, D. Quantification of household food waste in Hungary: A replication study using the FUSIONS methodology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, P.; Hák, T.; Janoušková, S. An analysis of food waste in Czech households—A contribution to the international reporting effort. Foods 2021, 10, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katajajuuri, J.M.; Silvennoinen, K.; Hartikainen, H.; Heikkilä, L.; Reinikainen, A. Food waste in the Finnish food chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Lopez, J.; Patinha Caldeira, C.; De Laurentiis, V.; Sala, S. Brief on Food Waste in the European Union; Avraamides, M., Ed.; JRC121196; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ladele, O.; Baxter, J.; van der Werf, P.; Gilliland, J.A. Familiarity breeds acceptance: Predictors of residents’ support for curbside food waste collection in a city with green bin and a city without. Waste Manag. 2021, 131, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y.T.; Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; O’Connor, P.J. Household food waste disposal behaviour is driven by perceived personal benefits, recycling habits and ability to compost. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, D.; Hassan, K.A. Factors influencing household food waste behaviour in Malaysia. Int. J. Res. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 3, 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ilakovac, B.; Iličković, M.; Voća, N. Food waste drivers in Croatian households. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2018, 19, 678–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, S.; Grappi, S.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Barone, A.M. Domestic food practices: A study of food management behaviors and the role of food preparation planning in reducing waste. Appetite 2018, 121, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, B.N. Turn Leftover into Nutritious Meals, Reduce Food Wastage. 2017. Available online: https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2017/10/286917/turn-leftovers-nutritious-meals-reduce-food-wastage (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Farr-Wharton, G.; Foth, M.; Choi, J.H.-J. Identifying factors that promote consumer behaviours causing expired domestic food waste. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelli, E.; Francioni, B.; Curina, I. Healthy lifestyle and food waste behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.C.; Chih, C.; Yang, W.J.; Chien, C.H. Determinants and prevention strategies for household food waste: An exploratory study in Taiwan. Foods 2021, 10, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, W.-Z.; Narayanan, S.; Hong, M. Responsible consumption: Addressing individual food waste behavior. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 3245–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Kumar, S.; Salo, J.; Dhir, A. The balancing act: How do moral norms and anticipated pride drive food waste/reduction behaviour? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; O’Connor, P.J. Motivations behind daily preventative household food waste behaviours: The role of gain, hedonic, normative, and competing goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 43, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörissen, J.; Priefer, C.; Bräutigam, K.-R. Food waste generation at household level: Results of a survey among employees of two European research centers in Italy and Germany. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2695–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizeau, K.; von Massow, M.; Martin, R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visschers, V.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, J.; Karunasena, G.; Kansal, M.; Mitsis, A.; Pearson, D. Quantifying the effects of food management routines on household food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391, 136230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkman, A.; van Doorn, J.; van Ittersum, K.; Kok, A. No waste like home: How the good provider identity drives excessive purchasing and household food waste. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 103, 102564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Acquaye, A.; Khalfan, M.M.; Obuobisa-Darko, T.; Yamoah, F.A. Decoding sustainable consumption behavior: A systematic review of theories and models and provision of a guidance framework. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2024, 23, 200232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.A.; Ma, Y.; Reza, M.N.H.; Ahmad, J.; Wan, H.W.M.H.; Lili, Z. Predicting attitude and intention to reduce food waste using the environmental values-beliefs-norms model and the theory of planned behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 120, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, V.; Gombos, S. Household food waste reduction determinants in Hungary: Towards understanding responsibility, awareness, norms, and barriers. Foods 2025, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrank, J.; Hanchai, A.; Thongsalab, S.; Sawaddee, N.; Chanrattanagorn, K.; Ketkaew, C. Factors of food waste reduction underlying the extended theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer behavior towards the intention to reduce food waste. Resources 2023, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.D.; Kaur, P.; Sharma, V.; Talwarf, S. Analyzing the food waste reduction intentions of UK households. A Value-Attitude-Behavior (VAB) theory perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloysius, N.; Ananda, J.; Mitsis, A.; Pearson, D. Why people are bad at leftover food management? A systematic literature review and a framework to analyze household leftover food waste generation behawior. Appetite 2023, 186, 106577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; Ujang, Z.B. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manika, D.; Iacovidou, E.; Canhoto, A.; Pei, E.; Mach, K. Capabilities, opportunities and motivations that drive food waste disposal practices: A case study of young adults in England. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 33449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloysius, N.; Ananda, J.; Mitsis, A.; Pearson, D. The last bite: Exploring behavioural and situational factors influencing leftover food waste in households. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 123, 105327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynarski, S. Analiza Danych Rynkowych i Marketingowych z Wykorzystaniem Programu Statistica; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stanisz, A. Modele Regresji Logistycznej. Zastosowania w Medycynie, Naukach Przyrodniczych i Społecznych; Wydawnictwo StatSoft Polska: Kraków, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Redlingshöfer, B.; Barles, S.; Weisz, H. Are waste hierarchies effective in reducing environmental impacts from food waste? A systematic review for OECD countries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z dnia 13 Września 1996 r. o Utrzymaniu Czystości i Porządku w Gminach. Dz.U.2025.733.

- Bioodpady Komunalne Posegregowane i Poddawane Recyklingowi u źródła w Polsce 2024; Instytut Ochrony Środowiska–Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2025; p. 56.

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, G.; Phillips, C. Food waste and domestic refrigeration: A visceral and material approach. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2016, 17, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.J.; Lin, S.M.Y.; Huang, L.Y. Sharing leftover food with strangers via social media: A value perspective based on beliefs-values-behavior framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.C.; Ojha, A.; Debnath, S.; Sharma, M.; Nayak, P.K.; Sridhar, K.; Inbaraj, B.S. Valorization of food waste as animal feed: A step towards sustainable food waste management and circular bioeconomy. Animals 2023, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Wasted Food Scale. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/wasted-food-scale (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- van Geffen, E.J.; van Herpen, H.W.I.; van Trijp, J.C.M. Causes & Determinants of Consumers Food Waste; Project Report, EU Horizon 2020 REFRESH; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Janssens, K.; Lambrechts, W.; van Osch, A.; Semeijn, J. How consumer behavior in daily food provisioning affects food waste at household level in the Netherlands. Foods 2019, 8, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivupuro, H.K.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.M.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of socio-demographical, behavioural and attitudinal factors on the amount of avoidable food waste generated in Finnish households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, L.; Francioni, B.; Murmura, F.; Savelli, E. Factors affecting household food waste among young consumers and actions to prevent it. A comparison among UK, Spain and Italy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Huang, L.; Liang, X.; Bai, L. Consumer knowledge, risk perception and food-handling behaviors—A national survey in China. Food Control 2021, 122, 107789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Böhme, T.; Geiger, S.M. Measuring young consumers’ sustainable consumption behavior: Development and validation of the YCSCB scale. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kymäläinen, T.; Seisto, A.; Malila, R. Generation Z food waste, diet and consumption habits: A Finnish social design study with future consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Ben Ismail, H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaivalappil, A.; Papadopoulos, A.; Young, I. Intentions to adopt safe food storage practices in older adults an application of the theory of planned behaviour. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittuari, M.; Herrero, L.G.; Masotti, M.; Iori, E.; Caldeira, C.; Qian, Z.; Bruns, H.; van Herpen, E.; Obersteiner, G.; Kaptan, G.; et al. How to reduce consumer food waste at household level: A literature review on drivers and levers for behavioural change. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secondi, L.; Principato, L.; Laureti, T. Household food waste behaviour in EU-27 countries: A multilevel analysis. Food Policy 2015, 56, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska, B.; Tomaszewska, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Analysis of the behaviors of Polish consumers in relation to food waste. Sustainability 2020, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, I.C.; Harun, R.; Andreica, I.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Kovacs, E.; Oroian, C.F.; Brata, A.M.; Dumitras, D.E. Household attitudes and behavior towards the food waste generation before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Romania. Agronomy 2022, 12, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miafodzyeva, S.; Brandt, N. Recycling behaviour among householders: Synthesizing determinants via a meta-analysis. Waste Biomass Valorization 2013, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, T. Gifting, ridding and the “everyday mundane”: The role of class and privilege in food waste generation in Indonesia. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1444–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaili, T.M.; Obaid, R.S.; Alqutub, R.; Akkila, R.; Habil, A.; Dawoud, A.; Duhair, S.; Hasan, F.; Hashim, M.; Ismail, L.C.; et al. Food wastage attitudes among the United Arab Emirates population: The role of social media. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østergaard, S.; Hanssen, O.J. Wasting of fresh-packed bread by consumers—Influence of shopping behavior, storing, handling, and consumer preferences. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Talia, E.; Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Consumer behaviour types in household food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckli, S.; Niklaus, E.; Dorn, M. Call for testing interventions to prevent consumer food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, M.; Bilska, B.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Do Polish consumers take proper care of hygiene while shopping and preparing meals at home in the context of wasting food? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Balaine, L. Consumers’ perceptions of food waste: A pilot study of US students. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangherlin, I.D.C.; de Barcellos, M.D. Drivers and barriers to food waste reduction. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2364–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laila, A.; von Massow, M.; Bain, M.; Parizeau, K.; Haines, J. Impact of COVID-19 on food waste behaviour of families: Results from household waste composition audits. Soc. Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananda, J.; Karunasena, G.G.; Pearson, D. Has the COVID-19 pandemic changed household food management and food waste behavior? A natural experiment using propensity score matching. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 328, 116887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Group | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 51.1 |

| Men | 48.9 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 8.3 |

| 25–34 | 19.0 | |

| 35–44 | 18.0 | |

| 45–59 | 27.4 | |

| over 60 years | 27.4 | |

| Inhabitancy | Villages | 38.2 |

| Cities up to 50,000 | 24.8 | |

| Cities 50,001–100,000 | 7.4 | |

| Cities 100,001–200,000 | 9.1 | |

| Cities 200,001–500,000 | 9.0 | |

| Cities over 500,000 | 11.6 | |

| Education level | Primary | 8.4 |

| Basic vocational | 31.9 | |

| Secondary | 42.0 | |

| Higher | 17.7 | |

| No. of people over 18 years in household | 1 | 17.2 |

| 2 | 61.2 | |

| 3 | 16.3 | |

| 4 or more | 5.3 | |

| No. of children in household | 0 | 74.6 |

| 1 | 16.3 | |

| 2 | 7.6 | |

| 3 or more | 1.4 | |

| Portion of the household budget for food expenditure | Large (100–61%) | 12.3 |

| Average (60–40%) | 50.2 | |

| Small (39–0%) | 27.7 | |

| Hard to say | 9.8 | |

| Employment status of the person | Working | 66.4 |

| Not working (unemployed homemaker, including maternity/parental leave, pensioner/disability, student | 33.6 |

| Methods | Answers | No., % of Respondents | Descriptive Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | M(X) | Min/ Max | SD | Mode | % Mode | Mdn | ||

| other dishes | always (1) | 49 | 4.39 | 3.11 | 1.00/5.00 | 1.01 | 3.00 | 43.39 | 3.00 |

| usually (2) | 232 | 20.81 | |||||||

| sometimes (3) | 466 | 41.79 | |||||||

| rarely (4) | 207 | 18.57 | |||||||

| never (5) | 120 | 10.76 | |||||||

| hard to say | 41 | 3.68 | excl * | ||||||

| family and friends | always (1) | 9 | 0.81 | 4.02 | 1.00/5.00 | 1.02 | 5.00 | 43.18 | 4.00 |

| usually (2) | 81 | 7.26 | |||||||

| sometimes (3) | 254 | 22.78 | |||||||

| rarely (4) | 264 | 23.68 | |||||||

| never (5) | 462 | 41.43 | |||||||

| hard to say | 45 | 4.04 | excl * | ||||||

| freeze | always (1) | 28 | 2.51 | 3.52 | 1.00/5.00 | 1.07 | 3.00 | 36.25 | 3.00 |

| usually (2) | 148 | 13.27 | |||||||

| sometimes (3) | 389 | 34.89 | |||||||

| rarely (4) | 255 | 22.87 | |||||||

| never (5) | 253 | 22.69 | |||||||

| hard to say | 42 | 3.77 | excl * | ||||||

| animals | always (1) | 100 | 8.97 | 3.43 | 1.00/5.00 | 1.30 | 5.00 | 28.96 | 3.00 |

| usually (2) | 164 | 14.71 | |||||||

| sometimes (3) | 296 | 26.55 | |||||||

| rarely (4) | 203 | 18.21 | |||||||

| never (5) | 311 | 27.89 | |||||||

| hard to say | 41 | 3.68 | excl * | ||||||

| compost | always (1) | 20 | 1.79 | 4.30 | 1.00/5.00 | 1.05 | 5.00 | 62.38 | 5.00 |

| usually (2) | 70 | 6.28 | |||||||

| sometimes (3) | 142 | 12.74 | |||||||

| rarely (4) | 169 | 15.16 | |||||||

| never (5) | 665 | 59.64 | |||||||

| hard to say | 49 | 4.39 | excl * | ||||||

| container | always (1) | 47 | 4.22 | 3.65 | 1.00/5.00 | 1.13 | 4.00 | 31.70 | 4.00 |

| usually (2) | 131 | 11.75 | |||||||

| sometimes (3) | 266 | 23.86 | |||||||

| rarely (4) | 342 | 30.67 | |||||||

| never (5) | 293 | 26.28 | |||||||

| hard to say | 36 | 3.23 | excl * | ||||||

| Methods | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | Inhabitancy | Education Level | No. of Adults | No. of Children | Budget for Food | Employment Status | |

| other dishes | 0.006 * | 0.063 | 0.018 * | 0.609 | 0.062 | 0.385 | 0.695 | 0.144 |

| family and friends | 0.821 | 0.722 | 0.003 * | 0.230 | 0.594 | 0.991 | 0.000 * | 0.806 |

| freeze | 0.034 * | 0.002 * | 0.000 * | 0.233 | 0.019 * | 0.174 | 0.120 | 0.707 |

| animals | 0.440 | 0.153 | 0.000 * | 0.040 * | 0.000 * | 0.001 * | 0.197 | 0.451 |

| compost | 0.570 | 0.983 | 0.000 * | 0.636 | 0.429 | 0.786 | 0.000 * | 0.837 |

| container | 0.330 | 0.003 * | 0.000 * | 0.010 * | 0.227 | 0.005 * | 0.006 * | 0.000 * |

| Characteristics | Group | Methods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other Dishes n = 1074 | Family and Friends n = 1070 | Freeze n = 1073 | Animals n = 1074 | Compost n = 1066 | Container n = 1079 | ||

| gender | women | 3.19 a | 4.04 | 3.60 a | 3.40 | 4.30 | 3.62 |

| men | 3.03 b | 4.00 | 3.45 b | 3.46 | 4.31 | 3.68 | |

| age | 18–24 | 3.27 | 3.93 | 3.67 ab | 3.57 | 4.36 | 3.69 ab |

| 25–34 | 3.20 | 4.08 | 3.67 a | 3.55 | 4.31 | 3.42 b | |

| 35–44 | 3.04 | 4.07 | 3.29 c | 3.46 | 4.34 | 3.61 ab | |

| 45–59 | 3.14 | 4.01 | 3.59 ab | 3.27 | 4.27 | 3.69 a | |

| over 60 years | 3.00 | 3.97 | 3.45 bc | 3.45 | 4.29 | 3.80 a | |

| inhabitancy | villages | 3.17 a | 4.00 b | 3.51 b | 2.96 c | 3.98 c | 3.93 a |

| cities up to 50,000 | 2.99 b | 3.97 bc | 3.41 b | 3.69 b | 4.44 b | 3.48 b | |

| cities 50,001–100,000 | 2.90 b | 4.06 ab | 3.28 b | 3.59 b | 4.50 ab | 3.42 b | |

| cities 100,001–200,000 | 3.29 a | 3.73 c | 3.45 b | 3.51 b | 4.31 b | 3.61 b | |

| cities 200,001–500,000 | 3.18 ab | 4.08 ab | 3.85 a | 3.71 b | 4.78 a | 3.42 b | |

| cities over 500,000 | 3.12 ab | 4.33 a | 3.76 a | 4.05 a | 4.58 ab | 3.45 b | |

| education level | primary | 3.17 | 3.96 | 3.61 | 3.16 c | 4.30 | 3.88 a |

| basic vocational | 3.14 | 3.99 | 3.50 | 3.34 bc | 4.28 | 3.74 a | |

| secondary | 3.10 | 4.08 | 3.57 | 3.48 ab | 4.32 | 3.54 b | |

| higher | 3.05 | 3.94 | 3.39 | 3.60 a | 4.32 | 3.65 ab | |

| no. of adults | 1 | 3.22 | 3.98 | 3.70 a | 3.73 a | 4.33 | 3.60 |

| 2 | 3.14 | 4.05 | 3.51 b | 3.46 b | 4.32 | 3.64 | |

| 3 | 2.96 | 3.93 | 3.43 b | 3.15 c | 4.29 | 3.67 | |

| 4 or more | 2.90 | 4.03 | 3.28 b | 3.02 c | 4.04 | 3.93 | |

| no. of children | 0 | 3.13 | 4.02 | 3.56 | 3.42 b | 4.29 | 3.71 a |

| 1 | 3.11 | 4.03 | 3.45 | 3.66 a | 4.36 | 3.42 b | |

| 2 | 3.96 | 4.01 | 3.31 | 3.18 bc | 4.29 | 3.51 ab | |

| 3 or more | 2.94 | 4.00 | 3.38 | 2.56 c | 4.19 | 3.88 ab | |

| budget for food | large (100–61%) | 3.14 | 3.70 c | 3.32 | 3.19 | 3.80 b | 3.49 b |

| average (60–40%) | 3.11 | 4.14 a | 3.51 | 3.48 | 4.37 a | 3.59 b | |

| small (39–0%) | 3.06 | 3.93 b | 3.55 | 3.49 | 4.37 a | 3.84 a | |

| hard to say | 3.19 | 4.04 ab | 3.72 | 3.32 | 4.37 a | 3.67 ab | |

| Employment status of the person | Working | 3.13 | 4.01 | 3.52 | 3.46 | 4.29 | 3.59 b |

| Not working | 3.06 | 4.04 | 3.52 | 3.37 | 4.32 | 3.77 a | |

| The Independent Variables | df | F | p | η2P | Power Observed | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gender | 1 | 0.73 | 0.394409 | 0.000674 | 0.136240 | 8 |

| age | 4 | 3.596 | 0.006396 * | 0.013214 | 0.874759 | 2 |

| inhabitancy | 5 | 8.936 | 0.000000 * | 0.039974 | 0.999915 | 1 |

| education level | 3 | 3.436 | 0.016452 * | 0.009498 | 0.773324 | 5 |

| no. of adults | 3 | 1.370 | 0.250567 | 0.003808 | 0.366358 | 7 |

| no. of children | 3 | 4.053 | 0.007057 * | 0.011185 | 0.844048 | 4 |

| budget for food | 3 | 4.299 | 0.005030 * | 0.011854 | 0.866494 | 3 |

| employment status | 1 | 5.64 | 0.017738 * | 0.005209 | 0.660064 | 6 |

| Explanatory Variable | R_Yes (1) a | R_No (0) b | X2 | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | M(X) | Mdn | % | M(X) | Mdn | |||

| Frequency of purchase of chilled ready meals (n = 1057) ** | ||||||||

| every day (1) | 0.0 | 4.51 | 4.00 | 0.3 | 4.93 | 5.00 | 50.05 | 0.00 |

| every other day on average (2) | 1.9 | 0.5 | ||||||

| 1–2 times a week on average (3) | 13.0 | 7.4 | ||||||

| 1–2 times a month on average (4) | 37.1 | 24.6 | ||||||

| less than once a month (5) | 28.4 | 32.3 | ||||||

| never (6) | 19.6 | 34.9 | ||||||

| Frequency of purchase of frozen food, including ready meals (n = 1059) ** | ||||||||

| every day (1) | 0.2 | 4.42 | 4.00 | 0.2 | 4.78 | 5.00 | 35.85 | 0.00 |

| every other day on average (2) | 1.4 | 0.5 | ||||||

| 1–2 times a week on average (3) | 13.8 | 7.7 | ||||||

| 1–2 times a month on average (4) | 38.4 | 29.2 | ||||||

| less than once a month (5) | 32.7 | 37.4 | ||||||

| never (6) | 13.5 | 25.0 | ||||||

| Importance of the price of purchased products (n = 944) * | ||||||||

| definitely important (1) | 51.0 | 1.58 | 1.00 | 59.9 | 1.51 | 1.00 | 13.18 | 0.01 |

| rather important (2) | 40.9 | 32.8 | ||||||

| neither important nor unimportant (3) | 6.7 | 4.5 | ||||||

| rather unimportant (4) | 1.4 | 2.1 | ||||||

| definitely unimportant (5) | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||||||

| Importance of storage conditions of purchased products (n = 942) * | ||||||||

| definitely important (1) | 31.6 | 2.02 | 2.00 | 43.5 | 1.80 | 2.00 | 15.957 | 0.00 |

| rather important (2) | 45.9 | 39.0 | ||||||

| neither important nor unimportant (3) | 14.0 | 12.2 | ||||||

| rather unimportant (4) | 5.7 | 4.0 | ||||||

| definitely unimportant (5) | 2.9 | 1.3 | ||||||

| Frequency of preparing meals (n = 1108) ** | ||||||||

| always (1) | 27.7 | 2.37 | 1.00 | 32.5 | 2.52 | 1.00 | 27.74 | 0.00 |

| usually (2) | 30.9 | 19.2 | ||||||

| sometimes (3) | 21.1 | 20.4 | ||||||

| rarely (4) | 16.9 | 20.0 | ||||||

| never (5) | 3.4 | 7.9 | ||||||

| Frequency of washing hands before preparing meals (n = 1036) ** | ||||||||

| always (1) | 57.3 | 1.63 | 1.00 | 68.3 | 1.51 | 1.00 | 17.79 | 0.00 |

| usually (2) | 27.4 | 17.7 | ||||||

| sometimes (3) | 11.1 | 9.3 | ||||||

| rarely (4) | 3.3 | 4.3 | ||||||

| never (5) | 0.9 | 0.4 | ||||||

| Explanatory Variable | Model Parameters | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient β1 | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value | −95% CI | +95% CI | Wald’s Chi-Square | OR | |

| Frequency of preparing a shopping list | 0.101 | 0.067 | 1.513 | 0.131 | −0.030 | 0.232 | 2.289 | 1.106 |

| Frequency of purchase of chilled ready meals | −0.291 | 0.096 | −3.018 | 0.003 * | −0.480 | −0.102 | 9.111 | 0.748 |

| Frequency of purchase of frozen food, including ready meals | −0.209 | 0.103 | −2.031 | 0.043 * | −0.411 | −0.007 | 4.127 | 0.811 |

| Importance of the price of purchased products | −0.108 | 0.109 | −0.987 | 0.324 | −0.322 | 0.107 | 0.975 | 0.898 |

| Importance of storage conditions | 0.283 | 0.087 | 3.247 | 0.001 * | 0.112 | 0.454 | 10.545 | 1.327 |

| School as the basis of current food handling | 0.540 | 0.297 | 1.819 | 0.069 | −0.043 | 1.123 | 3.309 | 1.16 |

| Frequency of preparing meals | −0.064 | 0.067 | −0.943 | 0.346 | −0.196 | 0.069 | 0.890 | 0.938 |

| Frequency of washing hands before preparing meals | −0.028 | 0.093 | −0.304 | 0.761 | −0.210 | 0.154 | 0.092 | 0.972 |

| Food waste is a social problem | 0.065 | 0.085 | 0.762 | 0.446 | −0.102 | 0.231 | 0.581 | 1.067 |

| Actual | Predicted | Share of Correctly Predicted Cases | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y = 1 | Y = 0 | ||

| Y = 1 | 125 | 242 | 34.05994 |

| Y = 0 | 88 | 429 | 82.97872 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomaszewska, M.; Bilska, B.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Managing Food Leftovers in Polish Households in Terms of the Food Waste Hierarchy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310552

Tomaszewska M, Bilska B, Kołożyn-Krajewska D. Managing Food Leftovers in Polish Households in Terms of the Food Waste Hierarchy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310552

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomaszewska, Marzena, Beata Bilska, and Danuta Kołożyn-Krajewska. 2025. "Managing Food Leftovers in Polish Households in Terms of the Food Waste Hierarchy" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310552

APA StyleTomaszewska, M., Bilska, B., & Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. (2025). Managing Food Leftovers in Polish Households in Terms of the Food Waste Hierarchy. Sustainability, 17(23), 10552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310552