Abstract

Food waste poses critical environmental, economic, and social challenges, with consumer behavior recognized as a key leverage point for intervention. Packaging plays a vital role in preserving food quality and reducing waste, yet its behavioral influence on household food waste (HFW) remains underexplored. This review systematically examines 52 studies investigating the impact of food packaging—excluding storage/date labeling—on consumer food waste (CFW) behaviors. Using a structured methodology, we classified studies by methodological design, geographic coverage, food types, and focal packaging features. The analysis reveals a dominant reliance on consumer surveys and short-duration diaries, with limited application of rigorous experimental methods. Geographically, the English-language literature is skewed toward high-income countries, particularly Australia and Europe, with notable gaps in regions such as Asia and Africa. Moreover, despite U.S. households discarding approximately 40% of their food, research coverage remains limited. The findings also expose a misalignment between research focus and consumer-perceived importance of packaging features; attributes such as transparency, grip/shape, and dispensing mechanisms are frequently rated as important by consumers but are under-represented in the literature. This review contributes by identifying these gaps, synthesizing behavioral evidence, and offering a roadmap for future research and design innovation. By better aligning packaging functionalities with real-world behaviors, this work supports the development of consumer-informed solutions to mitigate HFW and promote sustainable food systems.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Food waste is a pressing global issue with profound environmental, economic, and social implications [1]. It contributes to inefficiencies across the food supply chain, exacerbates food insecurity, and places unnecessary strain on ecological systems. Reducing food waste is widely recognized as a critical strategy for enhancing food system efficiency, lowering production costs, improving nutrition and food availability, and supporting environmental sustainability [2]. As the global population continues to grow, managing food demand through waste reduction becomes essential for building resilient and sustainable food systems [3].

Recent events highlight the urgency of addressing household food waste. In 2023, the USDA reported a rise in food insecurity [4] and a stagnation in food waste reduction efforts, with U.S. households continuing to discard approximately 40% of their food supply [5]. Simultaneously, public discourse around plastic packaging and sustainability has intensified, with several retailers in the U.S. and Europe experimenting with reduced-packaging or plastic-free initiatives [6]. While these efforts aim to minimize packaging waste, they have, in some cases, led to increased food spoilage, particularly for fresh produce and perishables [7].

In addition to recent packaging debates and food insecurity trends, earlier influential reports have underscored the strategic role of packaging in reducing household food waste. Notably, the 2016 ReFED Roadmap identified packaging adjustments as one of the three most impactful solutions for food waste reduction at the consumer level—alongside standardizing date labels and expanding consumer education campaigns [8]. These recommendations have been echoed by international initiatives such as the Champions 12.3 coalition and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which call for halving per capita food waste at retail and consumer levels by 2030 in developed countries (United States 2030 Food Loss and Waste Reduction Goal. https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/united-states-2030-food-loss-and-waste-reduction-goal (accessed on 2 June 2025); EU actions against food waste. https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/food-waste/eu-actions-against-food-waste_en) (accessed on 2 June 2025). Despite these global targets, progress remains slow, and a disconnect persists between packaging innovation and consumer practice. Furthermore, as environmental concerns have spurred retailers to reduce or eliminate packaging, emerging evidence warns that such shifts may inadvertently increase food spoilage if not carefully managed. Collectively, these developments highlight an urgent need to reconcile sustainability goals with practical food preservation strategies—making our focus on packaging-driven consumer food waste behavior both timely and critical.

Packaging plays a pivotal role in food preservation, yet its influence on consumer food waste behavior remains underexplored in the academic literature [9]. One challenge in studying this relationship stems from the varied and often inconsistent ways consumers interact with packaging at home. Research has shown that consumer handling frequently deviates from intended use—examples include removing packaging prematurely, piercing it to allow airflow, repacking items, or failing to utilize built-in features such as resealability [10,11]. Such practices diminish the protective functions of packaging and can accelerate spoilage, ultimately increasing food waste [9].

Despite packaging’s potential to prevent waste, it is rarely recognized as a contributing factor by consumers unless it causes inconvenience [12]. This low awareness extends to a lack of familiarity with packaging formats, materials, and technologies that can optimize food storage and extend product shelf-life [13]. Packaging is designed to fulfill multiple functions—such as resealability, portion control, product protection, and ease of handling—each of which can influence waste-related outcomes [9]. Advanced innovations, including active and intelligent packaging, offer even greater potential. Active packaging interacts with food by releasing or absorbing substances to prolong freshness, while intelligent packaging communicates quality and safety information through sensors and indicators [11,13,14].

Nonetheless, consumer attitudes toward packaging are often shaped by misconceptions. Many equate minimal or no packaging with higher freshness and nutritional value, leading to avoidance of packaged options [7]. Environmental concerns compound these views, with 90% of surveyed consumers perceiving packaging as more harmful than food waste itself [7]. However, life cycle assessment data challenge this perception: the greenhouse gas emissions from food waste vastly outweigh those from packaging—by ratios of 624:1 for ham, 370:1 for beef, and 178:1 for cucumbers [7,15]. Notably, nearly a quarter of consumers reported willingness to switch to packaged food if better informed about packaging’s waste-reduction benefits [7], underscoring the importance of education in shifting consumer behavior.

Post-purchase handling further illustrates gaps in consumer knowledge. Studies document a wide range of behaviors, from maintaining food in its original packaging until use to complete removal of the food from the original package to avoiding certain packaging materials altogether [10,11]. According to Sealed Air [7], almost half of consumers remove fresh food from its packaging shortly after purchase, potentially compromising its functionality and accelerating spoilage.

The literature identifies several packaging features that influence food consumption and waste. These include intuitive design and labeling [16], graphics that enhance appeal [17], shelf-life and freshness indicators [18], multi-pack formats [19], improved opening and resealing mechanisms [20], clear date labels [21], robust materials for physical protection [19], easy dispensing systems [19], ergonomic features [19], and visibility or transparency for product inspection [22]. Additionally, packaging that offers a variety of sizes can help better align with consumer needs and reduce over-purchasing [16].

Despite the breadth of functional possibilities (Figure 1), much of the public discourse and research continues to frame packaging as waste rather than as a waste prevention tool. This disconnect between packaging’s potential and consumer perception presents an opportunity for targeted education and design innovation to better align household practices with sustainability goals.

Figure 1.

Consumer confusion about packaging features as a contributing factor to food waste.

1.2. Aims and Contributions

Given the escalating global concern around household food waste (HFW) and the relatively underexplored role that packaging plays in influencing consumer behaviors, this review aims to systematically analyze and synthesize existing studies on packaging-driven food waste behaviors. While packaging has long been studied in contexts such as shelf-life extension, logistics, and environmental impact, its behavioral implications—particularly in how it affects consumer practices leading to waste—remain scattered and inconsistently addressed.

This paper contributes to the literature by conducting a structured and comprehensive review of empirical and conceptual studies that examine the intersection of packaging features (excluding storage/date labeling) and consumer food waste behavior. Specifically, we aim to achieve the following:

- (i)

- Classify and critique studies based on methodological approach, geographical coverage, food categories, and focal packaging features;

- (ii)

- Identify patterns, blind spots, and inconsistencies in current research—such as the low application of experimental designs, limited attention to diverse global contexts (notably Asia and Africa), and under-representation of packaging features like transparency, grip/shape, and dispensing functions;

- (iii)

- Compare research priorities with consumer-perceived importance of packaging features in reducing food waste, using recent survey data (e.g., [11]) as a benchmark;

- (iv)

- Provide a roadmap for future research, policy, and design innovation by highlighting critical gaps and proposing directions that integrate behavioral insights with packaging design and sustainability goals.

To our knowledge, this is the first review to holistically examine how packaging—not merely its materials or labeling—affects food waste at the consumer level through behavioral channels. We aim for our findings to support the development of more effective packaging systems that align with consumer needs, reduce consumer/household food waste, and promote sustainability across diverse cultural and market contexts.

We also note that while consumer food waste arises from a wide range of factors across the household food journey, this review intentionally narrows its focus to packaging-driven behaviors. The goal is not to provide a comprehensive review of all food waste drivers but rather to address a critical yet underexplored dimension: how specific packaging features influence household food waste. This narrower scope ensures conceptual clarity and contributes novel insights without overlapping existing reviews on broader determinants. Prior literature has identified key behavioral contributors to consumer food waste: during the pre-shopping phase, insufficient meal planning and the absence of shopping lists often lead to over-purchasing [23,24]; in the post-purchase stage, improper storage practices—such as incorrect refrigeration or misunderstanding shelf-life indicators—accelerate spoilage [25,26]; during meal preparation, limited culinary skills and overcooking frequently result in unnecessary leftovers [27,28]; in the consumption phase, food aversions, poor leftover management, and portioning errors are key contributors [29,30]; household characteristics also matter—larger households generate more waste overall, although families with children often waste less per capita [31,32]; situational factors like urban living have been associated with greater waste compared to rural areas [33]; and finally, psychological and emotional drivers, such as guilt, sustainability values, and knowledge, strongly influence waste-reducing intentions and behavior [34,35,36,37]. These studies provide essential background on the complexity of consumer food waste, but because our goal is to examine the packaging-specific behavioral pathways, they are excluded from the main body of this review.

2. Literature Review in More Detail

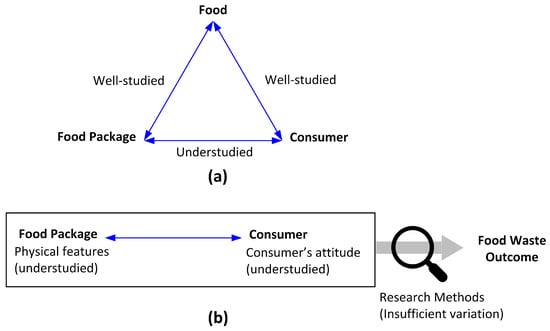

There exists a triangle with the vertices of food, consumers, and food packaging, where the edges—representing the interactions between these vertices—contribute to CFW. While extensive research has been conducted on the interactions between food and consumers [38] and between food and packaging [14] that contribute to CFW, the interaction between consumers and food packaging remains relatively underexplored [9]. This under-researched area is the focus of this paper.

2.1. Consumers’ Attitude Toward Food Packaging

The way consumers interact with food packaging is shaped by their attitudes toward it. Attitudes are influenced by three key components: knowledge, feelings, and actions/behaviors [39]. In this section, we will discuss each of these components separately.

Knowledge: There is a significant lack of consumer knowledge regarding the link between food packaging and CFW. Ref. [40] discovered that consumers rarely consider packaging to be a contributing factor in food waste unless they experience a direct inconvenience caused by it. Additionally, the absence of packaging is often overlooked as a potential cause of food waste. In the packaging-driven CFW literature, the research gap extends beyond the basic understanding of packaging’s role in reducing food waste. There is also a noticeable scarcity of information about consumer knowledge regarding various packaging formats, materials, features, and technologies, all critical for preserving food quality and significantly impacting CFW [41].

There is a wide variety of packaging formats, including but not limited to cartons, trays with plastic wraps, bags, boxes, cans, pouches, jars, bottles, and jugs. These utilize materials ranging from paper, plastic, and cardboard to metal, glass, textile, and wood. Packaging features are also integral to its functionality, directly or indirectly impacting CFW. Packaging features include a wide range of attributes. To name a few: ease of opening, closing, emptying, accessing, unpacking, dosing, carrying, pouring, gripping, stacking, and storing; keeping the product organized, compact, and appropriately portioned; being microwave-safe, transparent, and self-explanatory; and protecting the product from mechanical shocks, as well as the transmission, permeation, migration, and absorption of elements like light, gases, moisture, flavor, odor, particles, and microorganisms [9]. Innovative packaging technologies are also pivotal in reducing CFW. For example, active packaging incorporates components that release or absorb substances to prolong food shelf-life [41]. Another example is intelligent packaging, which engages in dynamic communication with consumers by actively monitoring and conveying the condition of the packaged food or its environment [14]. To this end, raising consumer awareness and understanding of packaging formats, materials, features, and technologies is essential for reducing food waste. With greater awareness, consumers are more likely to use packaging as intended—to preserve food quality—thereby contributing significantly to mitigating CFW.

Feelings: Previous studies indicate that consumer sentiment towards food packaging tends to be somewhat negative. The research in [7] and an article in [42] highlighted that most consumers perceive unpackaged foods as fresher and more nutritious than their packaged counterparts. Moreover, a striking 90% of consumers surveyed by [7] believed that the environmental impact of packaging is more detrimental than that of food waste. However, this perception is misguided. As demonstrated in [7], the greenhouse gas emissions ratios for various food products vs. their packaging suggest a significantly lesser impact from packaging: ham (624:1), beef (370:1), cucumber (178:1), whole chicken (114:1), cheese (52:1), fish (13:1), and pasta (7:1). Further evidence from [43] also compared the environmental impact of food packaging against that of three food products—ham, dark bread, and a fermented soy-based drink—reinforcing the fact that food waste has a greater environmental toll than packaging waste. Nevertheless, Ref. [7] claimed that nearly a quarter of consumers would switch from unpackaged to packaged food if they were better informed about the benefits of packaging in reducing food waste. This indicates a significant opportunity for further research into effective communication strategies, potentially through food packaging, regarding the value of packaging.

Actions/Behaviors: Research on how consumers handle food packaging after purchase is limited. These actions include but are not limited to leaving food in its original packaging until consumption, piercing the packaging to let it breathe, removing it entirely and leaving food exposed or repacking it, opting for unpackaged products, avoiding certain packaging formats and materials, and not utilizing packaging features, such as overlooking to reseal a package designed with a resealability function. Ref. [7] reported that nearly half of consumers remove fresh food from its original packaging shortly after purchase. Such behaviors undermine the packaging’s intended functions, reduce the product’s shelf-life, and significantly contribute to food waste.

Another example of improper consumer behavior toward food packaging involves their response to damaged packages. Some studies have examined how shoppers react to visual imperfections in packaging. For instance, Ref. [44] found that around 75% of shoppers would avoid purchasing frozen foods if the packaging showed visible damage. However, there are still many unknowns about how consumers handle packaging imperfections after purchase, which can directly contribute to CFW. Such damage may occur due to mishandling during transportation from the store to home or from not noticing the damage at the time of purchase.

The following subsections provide an in-depth review of 52 sampled studies and identify key gaps in the existing literature. The studies are examined through three distinct lenses: (1) the research methods employed, (2) the food types investigated, and (3) the packaging features analyzed. To ensure comprehensiveness and transparency, detailed information on each study is included in Appendix A.

2.2. Methods Used to Assess Packaging’s Impact on Food Waste

The methodologies used to evaluate the influence of packaging on CFW behaviors are diverse but heavily skewed toward exploratory and perceptual approaches. Consumer surveys (18 studies) are by far the most common, often capturing self-reported awareness, attitudes, or intended behavior [11,19,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. While surveys offer scalability and insight into large populations, they often fall short of revealing real behavioral outcomes. One important limitation of this approach is the tendency to underestimate actual consumer food waste due to several methodological challenges [53]. These include cognitive difficulties in estimating waste—stemming from confusion about what constitutes food waste and how to quantify it; social desirability bias, which leads participants to under-report behaviors that may be perceived negatively; and retrospective reporting, which relies on memory and often results in recall errors. Additionally, surveys typically yield correlational rather than causal insights, making it difficult to isolate the true drivers of food waste due to unobserved endogenous variables. Collectively, these issues contribute to substantial under-reporting, limiting the accuracy of survey-based findings on food waste behavior.

Diaries (9) and consumer interviews (7) are more detailed, providing context-rich insights into daily food management routines [12,16,21,46,54,55,56]. Several studies have combined diaries with interviews or journey mapping to build comprehensive narratives around food usage and waste [45,46,54]. However, diary methods come with several limitations. First, they impose a relatively high participant burden, which can lead to incomplete records, fatigue, or noncompliance over extended periods. Second, participants may unintentionally alter their behavior due to the act of self-monitoring, leading to more cautious food use and potentially underestimating actual waste (i.e., the Hawthorne effect). Third, the accuracy of diary entries may still be limited by recall error if participants delay recording events or fail to document smaller instances of waste. Finally, diary studies often attract participants who are more conscientious or food-waste-aware, introducing a selection bias that limits the generalizability of findings. These factors can compromise both the completeness and external validity of data gathered through diary methods.

Stakeholder consultations (5) and focus groups (1) were used to gather expert or community insights—especially within industry-linked research [41,57,58,59]. While useful for understanding barriers in packaging development, these methods often overlook actual consumer behavior. A small number of studies employed field experiments (4), lab experiments (1), optimization models (1), and secondary data analyses (1) [60,61,62,63], offering much-needed causal evidence or simulations of waste-reducing interventions. However, each of these methods has its limitations: field experiments, while ecologically valid, can be costly and logistically complex to implement at scale; lab experiments may lack realism, limiting generalizability to real-world settings; optimization models often rely on simplifying assumptions and idealized input data, which may not fully capture consumer behavior or supply chain variability; and secondary data analyses are constrained by the structure and quality of existing datasets, potentially omitting critical variables needed to understand the role of packaging in food waste.

Notably underused are design thinking, ethnography, and journey mapping—despite their proven value in uncovering nuanced consumer–package interactions [45,50,54]. Design thinking involves iterative, user-centered problem-solving that integrates consumer insights into packaging innovation; ethnography provides an in-depth, contextual understanding of food practices through immersive observation; and journey mapping traces the consumer’s experience with food and packaging over time, revealing critical touchpoints that influence waste-related behavior. There remains an opportunity to expand methodological diversity by integrating behavioral experiments, longitudinal tracking, and digital tools (e.g., smart packaging or sensors) to bridge the perception–behavior gap.

2.3. Food Types Studied in the Context of Packaging and Waste

Packaging’s impact on food waste is unevenly distributed across food types. The most commonly studied categories include dairy and eggs (29 studies), meat and fish (26), vegetables (25), bread (23), and fruits (21) [11,12,46,47,48,52,54,55,57]. These foods are highly perishable and sensitive to environmental exposure, making them prime candidates for packaging innovations that prevent spoilage or portion mismatch.

In contrast, processed foods (9), prepared meals (10), general non-specified items (5), drinks (3), snacks (1), and herbs (1) are rarely explored [54,57,58,59,64]. Yet these items also contribute to household waste, particularly due to misjudged shelf-life, confusion over storage, or bulk packaging formats.

Moreover, consumer perceptions vary across food types—e.g., meats are viewed as safety-sensitive, while fruits and vegetables are often discarded for cosmetic reasons [45,46,65]. This suggests that packaging interventions must be tailored not only to product perishability but also to consumer beliefs, routines, and category-specific expectations. Further research is needed on under-represented foods, especially shelf-stable and processed categories, where packaging may silently influence waste through size, confusion, or perceived redundancy.

2.4. Packaging Features Examined in the Literature

A wide range of packaging features have been investigated for their role in mitigating consumer food waste (CFW), with varying degrees of depth and consistency. Among these, resealability and date/storage labeling emerged as the most commonly studied features, each appearing in 17 studies [11,16,19,41,45,46,47,48,49,51,52,54,57,58,59,66,67]. These features are typically linked to improvements in shelf-life, usability, and planning efficiency.

Closely following are portioning (8 studies), packaging technologies such as MAP and vacuum sealing (8), and size (8), which influence food waste through consumer perceptions of quantity appropriateness and spoilage risk [11,12,41,46,58,59,63,66]. Material use and protection (7) was investigated for its dual impact on environmental perception and food safety [19,45,46,47,57,63,68]. However, more nuanced features—such as ease of opening, visibility, and easy-to-empty design—each appeared in only one–two studies [12,45,46], revealing a gap in the literature concerning the physical effort and interaction between consumer and package.

Interestingly, some of the most important packaging characteristics identified in consumer surveys, such as transparency, use/cook directions, dispensing mechanisms, and safety instructions [11,48,50], are almost entirely absent in the empirical packaging literature. This mismatch suggests that future studies should align more closely with consumer priorities, particularly by exploring packaging’s cognitive and behavioral affordances.

3. Review Methodology

To identify studies that have focused on packaging-driven consumer food waste (CFW) behavior, we conducted a structured literature review based on the methodologies of Tranfield et al. [69], Cooper [70], Mayring [71], and Cooper [72]. This approach comprises four steps: material collection, bibliometric analysis, content analysis, and material evaluation. While we discuss the first two steps in this section, the latter two will be addressed in Section 2 and Section 4, respectively.

3.1. Material Collection

The following inclusion criteria were defined prior to conducting the literature search:

- Studies that investigate consumer (household) food waste behaviors influenced by packaging features, materials, and formats—excluding (i) those focused solely on date or storage labeling (as extensively reviewed in the recent literature, e.g., Llagas et al. [73]), (ii) life cycle assessments where consumer behavior is only tangentially addressed, and (iii) technological aspects of packaging that aim to extend shelf-life and are purposefully designed to reduce food waste;

- Studies published in peer-reviewed academic journals, conference proceedings, or credible industry reports;

- Studies written in English.

Accordingly, this review focuses specifically on packaging-driven (excluding labeling) CFW behavior.

Our literature review methodology, which ultimately resulted in the selection of 52 studies, is summarized as follows (see Table 1 for additional details):

Table 1.

Summary of literature review methodology.

- We conducted a keyword-based search in the Scopus, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR databases using the following terms: “food packaging”, “packaging”, “consumer food waste”, “consumer food waste behavior”, “household food waste”, “household food waste behavior”, “food waste behavior”, and “packaging-driven food waste”. Articles were included if at least one of these keywords appeared in the title, abstract, or list of author-defined keywords. This initial search yielded a total of 1657 articles.

- Based on relevance, indicated by the titles, abstracts, and keywords, the sample was narrowed to 88 studies.

- Full-text screening of these 88 studies resulted in 43 papers deemed directly relevant, and these were retained for further analysis.

- A forward snowballing process was then applied, wherein the reference lists of the 43 selected studies were examined. This identified 11 additional studies, of which 7 met our relevance criteria and were added to the sample.

- A backward snowballing process was also conducted by reviewing all studies that cited the 43 selected papers. This led to 5 more papers, with 2 found to be relevant and included in the final sample.

Given the relatively small number of studies identified through this process (n = 52), we recognize that this review aligns more closely with the principles of a scoping review rather than a conventional systematic review. The limited literature reflects the emerging and understudied nature of research on packaging-driven CFW behavior, particularly beyond labeling. By mapping existing evidence and identifying key gaps, this review aims to advance understanding in a field that remains critically important yet underexplored—especially as packaging continues to play a central role in sustainability, food preservation, and waste mitigation efforts at the household level.

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis

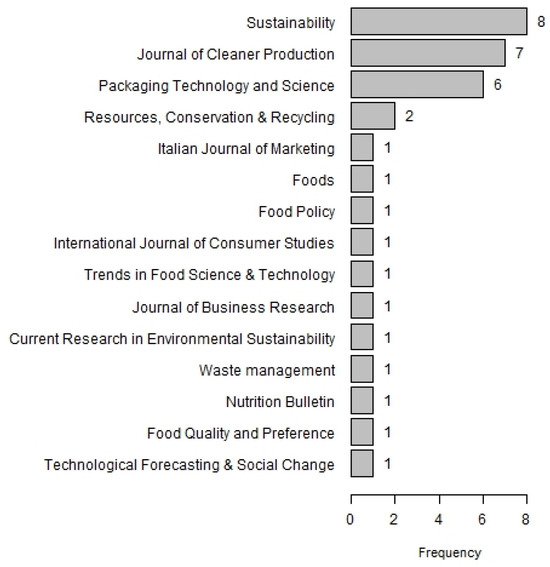

Figure 2 presents the frequency with which the academic articles appeared across different peer-reviewed journals. Sustainability (8), Journal of Cleaner Production (7), and Packaging Technology and Science (6) are the top three journals that have published the most articles on this topic. In addition, after analyzing the 52 sampled studies in detail, we classified them into two main categories: (1) review papers and (2) research works, whether published in academic journals, presented at conferences, or featured in industry reports. We identified 11 review papers specifically addressing packaging-driven consumer (household) food waste behavior.

Figure 2.

Frequency of papers in various academic journals.

The remaining research works were further categorized based on (i) the research methodology employed (see Figure 3), (ii) the country in which the study was conducted (see Figure 4), (iii) the food type examined (see Figure 5), and (iv) the packaging features emphasized in the study (see Figure 6).

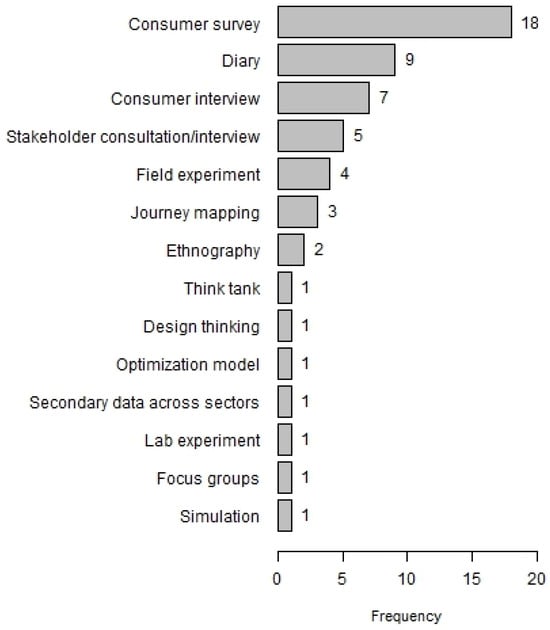

Figure 3.

Frequency of research methods.

Figure 4.

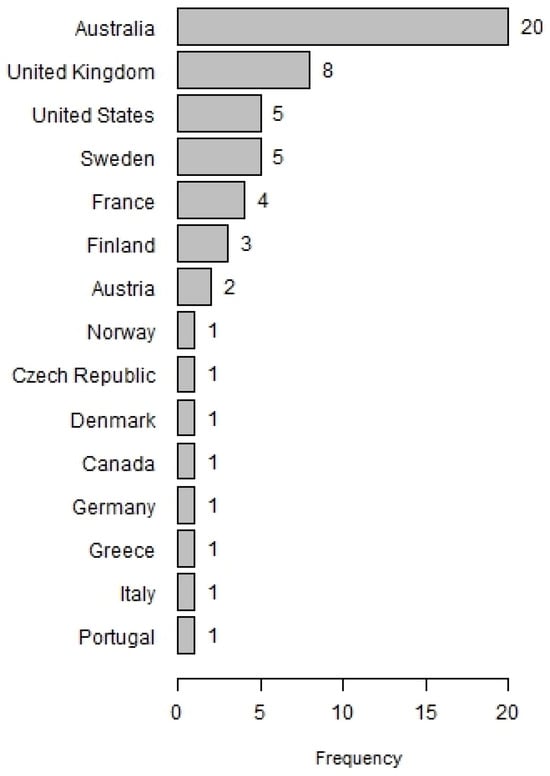

Frequency of studies in various countries.

Figure 5.

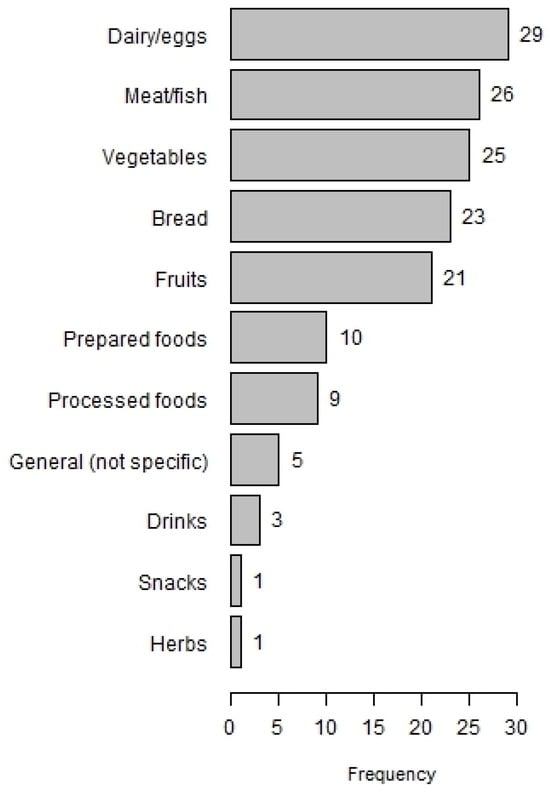

Frequency of food types.

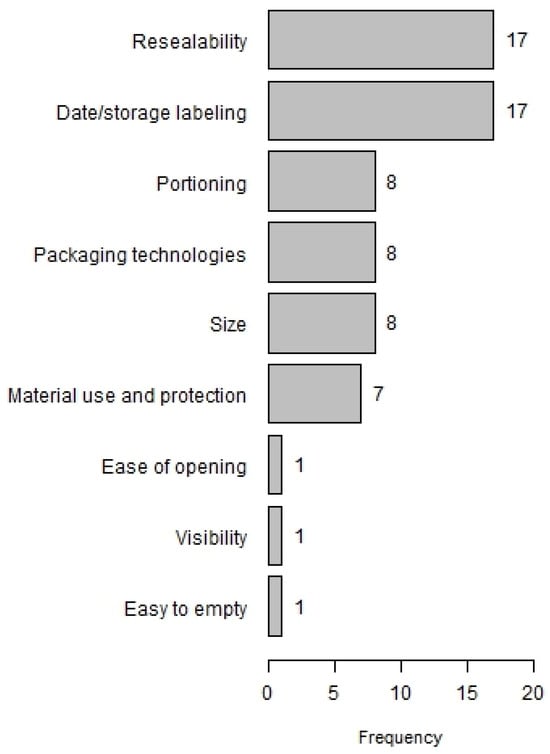

Figure 6.

Frequency of packaging features.

Figure 3 presents the distribution of research methodologies employed across the research works included in our sample. The most frequently used method was consumer surveys (n = 18), followed by diary studies (n = 9) and consumer interviews (n = 7). Stakeholder consultations or interviews (n = 5), field experiments (n = 4), and journey mapping (n = 3) were also employed, though less frequently. Diary studies, while offering insights into consumer routines and food waste behaviors, were typically short in duration—often limited to one week—thus capturing only a narrow temporal window of household practices. Experimental methods, including field (n = 4) and lab experiments (n = 1), were notably underutilized despite their potential to provide stronger causal inferences. This limited use may reflect the higher logistical complexity and resource demands of such designs. Overall, the distribution highlights a strong reliance on consumer-centered and self-reported methods, with relatively few studies applying rigorous experimental approaches to investigate packaging-driven food waste behaviors.

Figure 4 illustrates the geographic distribution of the research works included in our sample. Australia stands out as the dominant contributor to the literature on packaging-driven CFW, with 20 studies—more than double the next-highest country, the United Kingdom (n = 8). The United States and Sweden follow, each contributing five studies, despite the fact that U.S. consumers waste approximately 40% of their food annually (https://www.nrdc.org)—indicating a notable mismatch between the severity of the issue and the research focus. Other European countries such as France, Finland, and Austria are also represented, albeit at lower levels. However, studies from Asia, Africa, and South America are entirely absent from our sample of English-language publications, which may reflect a genuine lack of research in these regions—or, alternatively, the limited availability of such research in English. This highlights an important limitation in the evidence base and underscores the need for broader, cross-cultural investigations that can capture diverse consumer behaviors, packaging systems, and waste infrastructures around the world. Future reviews with multilingual capabilities would be well-positioned to address this gap and bring greater global representation to the field.

Including this geographic distribution is a common practice in review papers, particularly when addressing emerging or underexplored topics. The purpose of Figure 4 is primarily descriptive—aiming to visualize where research activity has been concentrated and highlight under-represented regions. This context not only helps identify geographic gaps but also supports future researchers in locating potential collaborators and understanding the cultural and systemic boundaries of existing evidence. Additionally, mapping study origins helps readers interpret whether the insights are likely shaped by specific policy, infrastructure, or consumer behavior contexts. Beyond this contextual function, no evaluative implications are drawn from the dominance of any particular country in the figure.

Figure 5 displays the frequency of food types addressed in the research works. The most commonly studied categories were dairy and eggs (n = 29), meat and fish (n = 26), vegetables (n = 25), bread (n = 23), and fruits (n = 21). These food groups are particularly prone to spoilage, short shelf-life, or portioning challenges, making them central to packaging-related food waste concerns. Other categories, such as prepared foods (n = 10) and processed foods (n = 9), also received moderate attention. However, certain categories—such as drinks, snacks, and herbs—were rarely studied (each n ≤ 3), and a small number of studies did not specify the food type explicitly. This distribution suggests that research has largely focused on perishables with high waste rates, yet more attention could be directed toward overlooked food categories and generalized packaging solutions that span multiple product types.

Figure 6 summarizes the packaging features emphasized in the literature on CFW behavior. Resealability and date/storage labeling were the most frequently examined features (each n = 17), followed by portioning, packaging technologies, and size (each n = 8). Material use and protection was slightly less prominent (n = 7), while ease of opening, visibility, and ease of emptying received minimal attention (each n = 1).

This distribution reveals a narrow research focus that may not fully reflect consumer priorities. For instance, a recent survey of 1000 U.S. consumers by Fennell et al. [11] evaluated the perceived importance of various packaging features in reducing food waste. While features such as food freshness (mean = 4.366), product dating (4.122), and protection (4.044) ranked among the highest, resealability (3.901) and size (3.882) followed closely behind. However, several features that consumers rated as moderately to highly important—such as use/cook directions (3.655), transparency (3.641), safety directions (3.604), and dispensing mechanisms (3.604)—have been almost entirely overlooked in the literature. Features like grip/shape design (3.440), eco-friendliness (3.391), and visual elements, such as illustrations or color (2.539), were also included by consumers but have received little scholarly attention in the context of food waste.

This misalignment between research emphasis and consumer perception points to the need for a broader and more consumer-informed research agenda. Future studies should expand beyond the dominant themes of labeling and resealability to examine underexplored yet meaningful packaging attributes that may influence real-world food waste behaviors.

To conclude this section, as illustrated in Figure 7, the relationship between food, consumers, and packaging has been unevenly explored in the literature. While the food–consumer and food–packaging links are relatively well studied, the direct interaction between packaging and consumer behavior—especially regarding physical features and attitudes—remains significantly underexplored. This review aims to shed light on these critical research gaps and emphasize the need for more diverse methodologies to assess how packaging influences food waste outcomes.

Figure 7.

(a) Underexplored interactions between food packaging and consumer behavior; (b) research gaps specifically related to these interactions.

4. Conclusions and Future Research Opportunities

In terms of context, there is a research gap in understanding the interaction between consumers and food packaging as it relates to consumer food waste (CFW). While considerable research has focused on food–consumer and food–packaging interactions, the consumer–packaging interface remains relatively underexplored. Specifically, there is a lack of consumer knowledge regarding how packaging formats, materials, and features influence food waste, as consumers often overlook packaging as a contributing factor unless it causes direct inconvenience. Furthermore, there is limited research on consumers’ understanding of advanced packaging technologies—such as active and intelligent packaging—and their potential role in reducing food spoilage. From an attitudinal perspective, most existing studies report that consumers hold negative perceptions of packaged foods, often viewing unpackaged items as fresher and more nutritious and significantly underestimating the environmental impact of food waste relative to packaging waste. This misperception highlights a critical gap in effective communication strategies that educate consumers about packaging’s role in preserving food. Behaviorally, very few studies have investigated how consumers interact with packaging post-purchase—such as repacking habits, misuse of resealable features, or handling of damaged packaging—which can undermine packaging functionality and contribute to increased waste. Collectively, these gaps underscore the need for targeted research to better understand and influence consumer attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors around food packaging in order to reduce CFW effectively.

This scoping review synthesizes a fragmented yet growing body of research on how packaging features influence CFW behavior. Our analysis of 52 studies reveals critical blind spots in existing scholarship. First, there is a methodological imbalance: surveys and short-term diaries dominate, while experimental and longitudinal designs remain rare. Second, research is geographically concentrated in high-income countries such as Australia and those in Europe. Notably, there is a complete absence of publications from Asia, Africa, and Latin America in our English-language sample. This gap may reflect either a true lack of research in these regions or linguistic inaccessibility to non-English studies—an inherent limitation in our methodology. Future multilingual reviews could provide a more inclusive global picture.

The implications of this study are both practical and conceptual. Practically, our findings reveal a persistent misalignment between the packaging features studied by researchers and those that consumers perceive as impactful in reducing food waste—such as transparency, intuitive dispensing systems, and freshness cues. This gap presents actionable opportunities for designers, retailers, and policy-makers to better match packaging solutions with real consumer needs and behaviors. Conceptually, this review reinforces the importance of viewing packaging not just as a sustainability challenge but as a behavioral tool that can either enable or undermine food preservation in the home. Based on these findings, we propose the following avenues for future research:

- Expand methodological rigor: Future studies should incorporate more experimental designs, including field and lab experiments, to establish causal relationships between packaging features and food waste outcomes. Mixed-methods research can also uncover nuanced behavioral patterns that surveys may miss.

- Broaden geographic scope: Research efforts must be extended to under-represented regions such as Asia, Africa, and Latin America. These regions face distinct infrastructural, cultural, and food system dynamics that may shape packaging interaction and waste behaviors differently.

- Investigate underexplored features: Packaging features such as transparency, shape/ergonomics, dispensing systems, and freshness indicators deserve greater empirical attention, particularly given their perceived importance among consumers. The role of intelligent and active packaging technologies also remains a promising yet underutilized area of inquiry.

- Address consumer handling behavior: Post-purchase packaging use—such as removal, repacking, and misuse of resealable functions—needs to be examined more systematically. Understanding these behaviors is essential for bridging the gap between packaging design and real-world functionality.

To this end, this study brings value to both scholars and practitioners by consolidating a fragmented evidence base and identifying clear, actionable research priorities. For researchers, it offers a roadmap of underexplored packaging features and methodological gaps. For practitioners—including packaging designers, retailers, and policy-makers—it underscores the behavioral mechanisms through which packaging can enable or undermine food waste reduction, thereby informing more effective and consumer-aligned packaging strategies.

While we propose a set of future research directions throughout the paper, it is important to recognize the limitations of our review. The exclusion of non-English publications limits our ability to capture the full scope of research globally, particularly in regions where food waste may follow different cultural, economic, or infrastructural patterns. Additionally, by excluding studies focused solely on labeling, life cycle assessments, or technological innovations, we narrowed our scope to emphasize behavioral interactions with physical packaging features. This trade-off was intentional to ensure clarity and specificity, but it may limit the applicability of our findings to broader packaging strategies.

In conclusion, by mapping existing evidence, identifying underexplored packaging features, and highlighting the behavioral disconnect between design and use, this review aims to advance the conversation around sustainable food packaging. Addressing consumer food waste through better packaging design holds transformative potential—if researchers, industry, and policy leaders can act in coordination with behavioral insights.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Tabulated Summary of Packaging-Driven Food Waste Behavior Studies

This section presents a detailed synthesis of the 52 selected publications, highlighting their research objectives, applied methodologies, study locations, focal food types, key findings, and packaging-related recommendations.

Table A1.

Summary of reviewed studies on packaging and consumer food waste behavior.

Table A1.

Summary of reviewed studies on packaging and consumer food waste behavior.

| Study | Aims | Method, Sample Size | Country | Food Types | Key Findings | Packaging Recommendations |

| [12] | To explore reasons for HFW, with special attention given to the role of packaging | Exploratory study using 7-day food waste diary; a total of 61 households (30 with environmental education) | Sweden | Fruit, vegetables, dairy, bread, meat/fish, prepared foods, drinks | A total of 20–25% of food waste linked to packaging (too large, hard to empty, best-before date); environmentally educated households wasted less and were more observant of packaging’s role | Improve emptying design; reduce pack size; enhance resealability; better best-before guidance; consider food type and household size when designing |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [13] | To review the existing literature on consumer perceptions of packaging in relation to food waste reduction | Systematised review of 345 papers (2014–2020), including peer-reviewed and grey literature | Global (mainly Europe, Australia, U.S., U.K., Sweden) | Bread, dairy, meat, fresh fruit/veg, snacks, refrigerated foods | Consumer perceptions of packaging underexplored; negative perception of plastic persists; low awareness of packaging’s role in food waste reduction | Improve communication of packaging functions; enhance resealability, portion size, storage guidance, and ease of emptying; integrate consumer education with packaging design |

| [74] | To examine how packaging contributes to or mitigates HFW across food categories and identify future research directions | Mixed-method systematic review of 43 primary consumer studies (2006–2020) | Global (mostly Europe; gaps in Africa, Asia, Middle East) | Bread, meat, dairy, fruits, vegetables, poultry, seafood, ready meals | Date labeling and large pack sizes are the most cited packaging drivers of HFW; limited research on packaging function efficacy; packaging role underappreciated in HFW studies | Improve clarity and legibility of date labels; offer a variety of appropriately sized packs; use resealable and portion-sized packaging; expand research beyond Europe to better design for diverse food routines |

| [9] | To compare packaging-related HFW solutions from the empirical literature and industry press releases to identify gaps and alignment | Comparative review of 60 empirical studies and 412 industry press releases (2006–2021) | Global (mostly Europe, North America, and Oceania) | Perishables: fruits, vegetables, bread, dairy, meat, poultry, seafood | Industry and research address different HFW drivers; industry focuses more on resealability and shelf-life, while research emphasizes labeling and portioning; both underrepresent accessibility features | Combine shelf-life extension, better resealability, and clear labeling; integrate consumer education; align industry practices with research insights; design solutions tailored to perishable food types and household routines |

| [16] | To investigate how packaging functions influence food waste across different product categories using a consumer-centered approach | Mixed-method multi-step study: questionnaire, food waste diary, and in-depth interviews; a total of 37 Swedish households | Sweden | Bread, dairy, meat/fish, fruit/veg, staples, drinks, cooked food | A total of 28% of food waste directly, and 21% possibly, linked to packaging functions; size, resealability, and safety labeling emerged as key design gaps | Design packaging that matches portion needs; improve reclosing and ease-of-emptying; provide clearer food safety information and storage guidance; apply an ‘outside-in’ design approach considering consumer use process |

| [19] | To explore Swedish consumers’ perceptions of food packaging and its role in environmentally sustainable development, with a focus on organic food | Internet survey with 157 Swedish consumers using both open- and closed-ended questions | Sweden | General food products, especially organic | Consumers strongly associate environmental sustainability with packaging material rather than its protective or waste-preventing functions; paper is perceived as “green,” plastic and metal as harmful | Improve consumer understanding of packaging’s protective function; promote packaging that balances material use with food protection; integrate packaging sustainability criteria into organic labeling standards |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [47] | To assess whether optimized packaging systems (resealability, portioning, Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP) can reduce food waste at the household level and how consumers perceive and use such packaging | Mixed-method study: online survey (1117 consumers), PoS interviews (240 shoppers), consumer simulation, and food diary (30 entries) | Austria | Tomatoes, strawberries, lettuce, cucumbers, mushrooms, cheese, meat, sausages | Optimized packaging extends shelf-life, but consumers often unpack or misuse it; only 23% recognize its role in FW prevention; majority see packaging waste as a bigger issue than food waste | Increase consumer education on proper use of packaging; promote resealable, portions, and MAP packaging; align packaging design with household storage behavior and shelf-life needs |

| [75] | To review how packaging contributes to or prevents Food Loss and Waste (FLW) along the food supply chain, including integration into LCA | Literature review of 88 studies and 17 framework references; focus on empirical + policy reports | Global | General packaged food across stages (household, retail, post-harvest) | Up to 25% of household FLW is packaging-related; key drivers include poor emptying, large portions, and misunderstanding of expiration dates; packaging often seen as waste rather than a protective tool | Design packaging for ease of emptying, portioning, resealing; clarify date labeling; promote consumer education and integrate FLW into LCA for accurate sustainability assessments |

| [11] | To assess U.S. consumers’ awareness, purchase intent, and willingness to pay for packaging that reduces HFW | Online survey with 1000 U.S. consumers; stratified by census-aligned demographics; Likert scale | United States | Cherries, milk, bread, chicken, peanut butter, and packaged foods using MAP, Vacuum Packaging (VP), Active Packaging (AP), Retort Packaging (RP), Aseptic Packaging (ASP), Intelligent Packaging (IP) | Awareness of packaging’s role in food freshness is low; education improved purchase intent; a total of 50% willing to pay more for packaging that reduces HFW; demographic and psychographic segments matter | Educate consumers on freshness-extending packaging; develop packaging based on consumer perceptions; integrate education with design for MAP, VP, IP, and other shelf-life-enhancing technologies |

| [76] | To propose a research agenda on how packaging can reduce FLW and contribute to United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDG) 12.3 | Expert-led forum and workshop, drawing from the literature, case studies, and stakeholder input; qualitative synthesis of priorities | Global (authors from Europe, U.S., Australia) | General food categories (meat, dairy, bread, fruits, vegetables, packaged goods) | Five research areas identified: (1) packaging functions and FLW data; (2) trade-offs in environmental impact; (3) LCA improvements; (4) food-waste-focused design; (5) aligned stakeholder incentives | Develop packaging with ease-of-use, portioning, and freshness protection; integrate food waste metrics in design, LCA, and stakeholder models; incentivize supply chains and consumers to adopt FLW-reducing packaging |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [14] | To identify how innovative packaging can help reduce post-CFW by analyzing ecological impact and The Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) insights | Literature synthesis with ecological footprint analysis (EFA) and U.K. WRAP data; includes case studies and consumer behavior insights | United Kingdom | Bread, yogurt, cheese, deli meats, fruits, vegetables, sauces | Packaging waste has minimal impact vs. food waste; top causes include portioning issues, lack of resealability, confusing date labels, and product residue | Promote portion-controlled packs, resealable and easy-empty formats, smart freshness/ripeness indicators, and shelf-life-extending packaging; focus on clear labeling and consumer usability to reduce avoidable waste |

| [46] | To examine consumer perceptions of food packaging and on-pack labeling in reducing HFW, and identify packaging design strategies to support waste reduction | Two qualitative studies: (1) journey mapping with 37 participants, and (2) in-depth interviews with 50 participants across Australia | Australia | Bread, dairy, meat, fruits/vegetables, processed foods, bakery items | Consumers prioritize reducing plastic over food waste; packaging’s protective role under-recognized; participants favor resealable, portion-sized packs and clear storage/date labels but rarely engage with such info | Promote consumer education on packaging’s food-saving role; improve clarity of date and storage labels; design packaging for ease of resealing, decanting, and portioning; balance environmental concerns with usability |

| [77] | To estimate the potential of optimized packaging in reducing food waste across fresh food categories in the U.S. | Literature review, cost-benefit analysis, and expert consultation with 45 stakeholders from retail, foodservice, packaging, and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) | United States | Fruits, vegetables, bread/bakery, meat, dairy and eggs | Optimized packaging can reduce food waste by 10–20%, particularly through extended shelf-life, portioning, and damage prevention; consumer aversion to packaging and industry resistance are key barriers | Promote MAP and vacuum packaging, portioned and reclosable formats; increase consumer education; align packaging design with shelf-life, usability, and sustainability trade-offs to support food waste reduction |

| [78] | To develop a terminology for packaging functions and features and analyze their indirect contributions to sustainable development | Conceptual paper based on literature review (39 sources), supported by feature clustering and qualitative synthesis | Sweden | General food and non-food products | Identified three core packaging functions (protect, facilitate handling, communicate) and 19 features; a total of 14 indirect positive effects were mapped, with reduced product waste being the most common | Use terminology to better integrate packaging into sustainability design; emphasize features like resealability, portioning, barrier protection, and ease of emptying for minimizing indirect environmental and social impacts |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [54] | To understand how consumers perceive and interact with packaging in the context of HFW, using journey mapping methodology | Qualitative journey mapping with 37 Australian consumers across five food categories; in-home interviews and diary-based reflections | Australia | Bakery, dairy/eggs, packaged/processed, fresh fruit/veg, fresh/frozen meat/seafood | Packaging often underappreciated for its protective functions; resealability, portioning, and on-pack information were inconsistently recognized; confusion around date labels and storage practices was common | Educate consumers on packaging’s protective and informative functions; promote resealable and portion-appropriate designs; include clear date label guidance and on-pack storage instructions; align packaging features with household needs and routines |

| [79] | To compare consumer perceptions of food packaging sustainability with scientifically assessed environmental impacts of different packaging materials | Narrative review comparing the literature on European consumer perception and LCAs using four indicators: Global Warming Potential (GWP), recycling rate, reuse rate, and biodegradability | Europe | Beverages, vegetables, fruits, meat, dairy, loose foodstuffs | Consumers often misjudge sustainability: overestimating glass and paper/cardboard, and underestimating plastic and its protective role; purchasing is driven more by emotions than science-based understanding | Design science-based packaging that aligns with consumer perception; improve eco-labeling; educate consumers about trade-offs in material impacts and the importance of food protection to prevent waste |

| [57] | To investigate U.K. consumer attitudes and behaviors around food packaging and HFW, and inform strategies for waste reduction | Mixed-method study: a total of 18 accompanied shops + in-home interviews and an online survey of 4000 U.K. consumers | United Kingdom | Perishable items: fruit, vegetables, dairy, bread, meat | A total of 60% of HFW due to not being used in time; many consumers misunderstand packaging’s role in prolonging freshness; packaging often viewed as wasteful, especially among older groups; younger and environmentally aware groups more open to packaging’s benefits | Improve clarity and prominence of storage guidance and date labels; increase reclosability and portioning; educate consumers on packaging’s food preservation role; counterbalance environmental concerns with food-saving messaging |

| [66] | To translate PhD research into actionable Save Food Packaging (SFP) criteria for industry, aligning packaging features with HFW drivers | A 4-year PhD project embedded in Fight Food Waste (FFW) Cooperative Research Centre (CRC); included literature reviews, interviews with 20 consumers and 11 industry experts; synthesis of three peer-reviewed papers | Australia | Bread, dairy, fruits/veg, meat, ready meals, snacks, grains, sauces, beverages | Identified misalignment between marketed SFP solutions and consumer needs; barriers include cost, unclear benefits, and lack of testing; emphasized packaging features like resealability, portioning, labeling clarity | Test packaging during design; implement resealable/portioning formats; proactively gather consumer feedback; clearly label SFP features; foster collaboration across industry, research, and consumers |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [80] | To identify packaging technologies that can reduce HFW and explore consumer perceptions of these innovations | Desk study, site audits in the U.K. and France, interviews with retailers/manufacturers, and qualitative consumer focus groups | United Kingdom and France | Bread, meat, cheese, vegetables, herbs, sauces, fruits, ready meals | Key barriers include lack of consumer understanding of food vs. packaging waste trade-offs; effective formats include resealable trays, zipper pouches, and portioned meat; education and fridge management also critical | Promote resealable/portioning features, easy-empty and freshness indicators (e.g., Time-Temperature Indicators (TTIs)); educate on packaging’s protective role and correct fridge temperatures; address perceived packaging waste through clear messaging |

| [55] | To assess the full environmental impact of bread in Norway and evaluate the role of packaging and consumer behavior in bread waste | LCA using primary and database data; included transport, consumer behavior, and waste scenarios; system boundaries cradle-to-grave | Norway | Bread | Ingredient production was the main hotspot; bread waste caused 15–20% of impacts; consumer strategies like freezing and using extra packaging helped reduce waste, but packaging itself had a low impact | Improve consumer packaging to extend freshness; consider smaller loaves; educate on packaging’s protective role; test cellulose/Polyethylene (PE)-coated alternatives that showed promise in Breadpack trials |

| [81] | To provide a strategic and practical framework for integrating sustainability into packaging design and supply chains using life cycle thinking | Book combining conceptual frameworks, LCA tools, case studies (e.g., Marks | Spencer, Nike, P&G), and stakeholder perspectives across chapters | Global (focus on Australia, U.K., U.S.) | Broad food and non-food product categories | Packaging must be optimized with the full product–system in mind; life cycle thinking, cross-functional alignment, and balanced trade-offs between protection and material use are essential to reducing waste and embedding sustainability |

| [59] | To identify packaging formats and technologies that could reduce food waste in U.K. households | Market survey, retailer/manufacturer interviews, and international retail audits; synthesis of in-home solutions and packaging technologies | U.K., France, U.S., Portugal | Bread, dairy, meats, fruits, vegetables, deli products, ready meals, snacks | Portion packs, resealables, TTIs, and MAP can extend shelf-life and reduce spoilage; many consumers unaware of packaging’s role; retail environments influence awareness | Promote portioning, resealability, freshness indicators (e.g., TTIs); embed on-pack storage info; highlight packaging’s role in food preservation to encourage behavioral change |

| [58] | To identify packaging opportunities to reduce food waste across the entire supply chain in Australia | Literature review and stakeholder interviews with 15 organizations in the food and packaging supply chain | Australia | Bread, dairy, meat, fruit/veg, processed foods | Packaging is often undervalued in reducing waste; misalignment exists between pack design and supply chain needs; shelf-life tech and fit-for-purpose packaging can reduce waste pre- and post-consumer | Design packaging with product–system fit; promote portioning, resealability, and MAP; educate consumers on date labels; align design with logistics and recovery systems |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [49] | To examine Italian consumers’ willingness to purchase active and intelligent packaging to reduce HFW | Web-based survey with 260 respondents; structural equation modeling based on an extended Theory of Planned Behavior framework | Italy | General packaged food products (e.g., dairy, bread, meat, fruits/vegetables) | Consumers were more willing to purchase intelligent packaging than active packaging; attitudes, awareness, planning routines, and perceived behavioral control were key predictors | Promote intelligent packaging with freshness indicators; educate consumers on safety and benefits of active packaging; align messaging with consumer planning behavior and food waste concerns |

| [68] | To identify how packaging innovations can reduce food waste across all supply chain stages in Australia | Literature review and interviews with 15 industry stakeholders; focused on commercial and industrial food waste | Australia | Bread, dairy, meat, fruits, vegetables, processed and fresh foods | Packaging plays a critical role in food protection and shelf-life; trade-offs between packaging and food waste must be optimized; distribution and food service sectors have greatest opportunities for impact | Design fit-for-purpose packaging; promote MAP and resealability; improve labeling clarity; adopt retail-ready and reusable packaging; align logistics with shelf-life and recovery systems |

| [82] | To reassess the environmental role of food packaging and explore how packaging innovations can support food waste reduction | Literature review of LCA studies, food packaging innovations, and environmental impact assessments across food categories | Global (European Union (EU) and international studies) | Bread, meat, dairy, beverages, fruits/vegetables, cereals | Packaging often wrongly blamed for high environmental impact; in many cases, it plays a key role in reducing food waste and overall footprint | Optimize packaging with food system fit; invest in shelf-life-extending technologies; apply biopolymers and active packaging for high-PREI (Protein-Rich, Essential Ingredient) products; include food waste in LCA to justify packaging improvements |

| [83] | To explore how physical and non-physical packaging attributes influence waste behavior in households | Mixed-method study: literature review, bin raids (n = 10), digital diary (n = 5), visual survey (n = 200+), and ethnography (n = 2) | United Kingdom | Bread, dairy, fruits, meat, packaged food (general) | Geometry (resealability, refillability), material, and perceived “ick” affect recycling/reuse; consumers often misreport behavior; packaging with higher perceived value is more likely to be diverted from landfill | Design packaging for resealability and ease of cleaning; improve recyclability cues; reduce proximity conflict with kitchen bin; promote reuse by increasing perceived value and utility |

| [51] | To examine consumer awareness, understanding, and acceptance of TTIs on food packaging across Europe | A total of 16 focus group discussions and a quantitative survey in Finland, Greece, France, and Germany | Finland, Greece, France, Germany | Refrigerated foods (e.g., meat, dairy, seafood) | Consumers showed interest and trust in TTIs but had limited knowledge; warmer countries associated stronger benefits; gaps existed between expectations and actual applications | Improve TTI design usability and visibility; educate consumers on interpreting TTIs; integrate TTI with trusted labeling to enhance acceptance and cold-chain transparency |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [84] | To reduce chicken meat waste through packaging innovations, enabling better portioning, freezing, and use timing | Design and consumer trial of seven packaging concepts; a total of 32 in-home trials by Co-op Taste Team; comparative carbon assessment | United Kingdom | Chicken meat (breasts, strips, goujons) | Divisible MAP tray allowed consumers to cut and use one side, freezing or storing the rest; up to 59% used pack in ways likely to reduce waste | Promote divisible trays enabling ‘eat-me/freeze-me’ use; improve labeling to guide freezing; enable partial pack use without compromising freshness; avoid extra tools or equipment to adopt the design |

| [85] | To assess U.K. consumer perceptions of food packaging in relation to food waste, recyclability, and innovation | Online survey with 6214 respondents across U.K. regions; stratified by age, region, and household role in food management | United Kingdom | Bread, dairy, meat, fruit/veg, packaged foods | Since 2012, awareness of packaging’s role in reducing food waste has increased; still, many consumers prioritize recyclability over food protection | Promote resealable, recyclable, and freshness-retaining packaging; use messaging that clarifies food-saving benefits; improve recyclability and labeling to address material concerns and trade-offs |

| [48] | To assess how visual and verbal attributes of eco-design packaging influence consumers’ food waste decisions | Two 2 × 2 between-subject online experiments on milk and cheese packaging with 304 Canadian consumers | Canada | Dairy products (milk and cheese) | Visual (e.g., resealability) and combined visual-verbal packaging significantly influenced food waste reduction intentions through perceived physical functions; health consciousness moderated these effects | Focus on physical-function-enhancing design (resealability, clarity); promote health and sustainability benefits; educate consumers on packaging functionality to bridge perception–performance gap |

| [41] | To review the literature on consumer perceptions of packaging’s role in HFW | Systematized literature review of 345 scholarly and grey literature sources (2014–2020) | Global (strong focus on Europe, Australia, and North America) | Bread, dairy, meat, fruits, vegetables, refrigerated food | Found a major gap in research on consumer understanding of packaging functions for waste prevention; highlighted packaging design features underexplored in relation to consumer needs | Investigate and improve consumer awareness of packaging functions; design packaging with clear communication, resealability, and food protection; promote co-design approaches for packaging innovation |

| [67] | To analyze how packaging functions influence HFW across product types using a service logic perspective | Literature review of 23 articles, and an expert workshop with 42 participants across academia, NGOs, and industry | Sweden | Bread, yogurt, cheese, milk, meat/fish, sausage, vegetables, salad | Key waste drivers include excessive pack size, unclear storage guidance, and poor resealability; consumers discard food due to confusion about shelf-life and spoilage risks | Tailor packaging to household size; improve reclosability, storage info, and clarity of date labels; reduce portions; consider protection post-opening as critical for perishable products |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [86] | To examine how anticipated food waste influences consumer preferences for large vs. small food packages | Four behavioral experiments with U.S. and French consumers (N~800 total); between-subject design | France, United States | Apple sauce, chocolate pudding, milk, water, yogurt | Larger packages lead to greater anticipated food waste and lower purchase intentions; this effect is stronger for perishables and when partitioning makes quantity more salient | Offer small or partitioned packages for perishables; reduce promotional messaging on large packs; use on-pack cues or priming to activate waste awareness |

| [65] | To explore the environmental and food waste implications of removing plastic packaging from fresh produce in U.K. supermarkets | Narrative review using secondary data from WRAP, Food Standards Agency (FSA), and consumer research; includes policy, LCA, and behavioral perspectives | United Kingdom | Fresh produce (e.g., apples, carrots, salad, tomatoes, bananas, peppers, lemons) | Removing plastic packaging may reduce plastic waste but increase food waste due to reduced shelf-life; moisture loss, temperature, and storage behavior strongly affect outcomes | Use recyclable plastic or airtight containers for high-moisture produce; maintain fridge < 5 °C; educate on optimal home storage; conduct full LCA before replacing plastic packaging |

| [20] | To explore barriers to implementing reclosable/resealable packaging that aligns with consumer needs to reduce HFW | Semi-structured interviews with 20 consumers and 11 industry professionals in Australia; Gioia method used for grounded theory development | Australia | Packaged food and beverages (e.g., pasta, chips, frozen vegetables, dairy) | Diverging industry vs. consumer priorities hinder packaging design to reduce HFW; consumers seek functionality, while industry prioritizes cost and sales; communication gaps persist | Broaden industry–consumer communication; clarify functional value on-pack; offer reclosable/resealable formats for everyday foods; align packaging with consumer storage routines and needs |

| [62] | To assess how date label language, package size, and product type influence CFW behavior | Laboratory auction experiment with 200 participants; a total of 18 randomized food items varying by size, shelf-life, and date label | United States | Yogurt, salad greens, ready-to-eat cereal | “Use by” labels triggered highest waste value; larger sizes and short shelf-life increased anticipated waste; consumers had lower willingness to pay for ambiguous date labels | Standardize date labels to reduce ambiguity; use “Use by” only for safety-critical perishables; offer smaller packs for perishable items to reduce premeditated waste |

| [87] | To explore how on-pack date labeling and storage information influence CFW behavior and identify design interventions | Literature review + interviews and design workshops with 12 consumers (Sweden) and 10 industry practitioners (Australia); activity theory framework | Sweden, Australia | Fresh produce, meat, bread, dairy | Confusion over date labels and lack of storage info cause premature disposal; social norms and sensory cues also shape food waste behavior; industry neglects post-purchase label usability | Standardize and contextualize date labels; include shelf-life after opening; use visual/sensory cues; develop AR-based packaging to extend label info and support decision-making at home |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [64] | To analyze food waste drivers across the Danish food supply chain and identify multi-stakeholder solutions | Case study based on policy, stakeholder initiatives, and secondary data across sectors | Denmark | Vegetables, meat, dairy, cereals, bakery items | Consumer confusion over date labels, large pack sizes, and poor planning contribute to household waste; private and public actors have initiated awareness campaigns and packaging improvements | Improve packaging accessibility and sizing; enhance protection to extend shelf-life; clarify date labels; promote circular economy through better food–waste–packaging integration |

| [88] | To identify key drivers of CFW and build a structural model of HFW behavior in the Czech Republic | Two-wave survey (pre- and during-COVID) with 1551 respondents analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) | Czech Republic | General household food (bread, produce, meat, dairy) | Food purchasing discipline (planning, shopping lists) most strongly reduces waste; food quantity and durability are key drivers of waste; price and frequency of purchase are not significant | Educate consumers on food planning; promote list-based shopping and portion awareness; date label education needed; pack sizes should align with consumption behavior |

| [56] | To analyze how household characteristics, behaviors, and attitudes affect avoidable food waste | A 2-week food waste diary with questionnaire; a total of 380 Finnish households (1054 people) | Finland | Bread, dairy, fruits/veg, ready meals, staples, meat | Larger households generated more waste overall; per capita waste was highest among single women; pack size mismatch was a significant factor in waste generation | Offer smaller portion sizes; match pack sizes to household type; improve consumer education on storage and planning; design packaging to support waste reduction through flexibility and clarity |

| [52] | To investigate Australian consumers’ perceptions of food packaging and its role in minimizing food waste | Online survey (EPPS: The Existing Perceptions of Packaging Survey); a total of 965 adult Australian consumers | Australia | Meat/seafood, bakery, dairy/eggs, processed foods, fruits/vegetables | Packaging waste was perceived as a greater environmental issue than food waste; women, older, and higher-income consumers were more motivated to reduce food waste; perceptions of packaging’s value varied across consumer clusters | Promote intuitive, resealable, portion-controlling designs; align packaging with household needs and raise awareness of food waste as an environmental issue |

| [89] | To review and synthesize research on sustainable packaging design from a consumer perspective | Systematic literature review of 52 peer-reviewed journal articles (2010–2020) | Multi-country (mainly Europe, North America, Asia) | Primarily food and beverages; personal/home care | Consumers associate sustainability with visual and structural cues (e.g., green color, recyclability); eco-friendly cues often misunderstood; packaging plays key role in food waste, especially via overpackaging and portion sizing | Design packaging with clear visual and structural sustainability cues; reduce overpackaging; improve functionality (resealability, ease of emptying); educate consumers on packaging symbols and material sustainability |

| Study | Focus | Methodology | Country | Food Type | Key Findings | Packaging Insights |

| [90] | To review the literature on consumer perceptions of food packaging in reducing food waste | Systematized literature review of peer-reviewed and grey literature (2014–2019) | Australia (focus); includes international literature | Meat/seafood, bakery, dairy/eggs, processed foods, fruits/vegetables | Packaging can reduce waste by extending shelf-life, supporting portion control, and clarifying storage and date labels; gaps exist in consumer understanding and acceptance | Design resealable, portion-sized, and intuitive packaging; improve communication on storage and expiration; align packaging innovation with consumer practices and sustainability targets |

| [91] | To explore consumer dependence on plastic packaging in fresh food and its contribution to waste | Qualitative interviews with 32 consumers | United Kingdom | Fresh fruits and vegetables, fresh meat, dairy | Consumers valued plastic for freshness, hygiene, and convenience; acknowledged waste but lacked clear alternatives; social norms and retailer practices heavily influenced behavior | Encourage design of environmentally friendly plastic alternatives that preserve freshness; align packaging interventions with behavioral nudges and retailer-led change |

| [60] | To assess the effect of resealable packaging on HFW | Field trial with 100 households comparing resealable vs. non-resealable packs | Norway | Perishable food items (specific categories not detailed) | Resealable packaging led to reduced food waste due to improved preservation and convenience | Promote the use of resealable packaging to enhance food preservation and reduce household waste |

| [61] | To develop a meal planning model that minimizes HFW, cost, and Greenhouse Gas Emission (GHGE) by incorporating package sizes | Optimization study using mixed-integer linear programming; a total of 263 recipes and Dutch household data | Netherlands | Dinner meals (vegetarian focus) | The model produced zero-waste meal plans by aligning meals with retail package sizes; showed trade-offs between waste, cost, and carbon emissions | Design flexible meal kits using retail package sizes; educate consumers on planning; prioritize GHGE alongside food weight as a performance metric |

| [63] | To investigate how packaging impacts food waste and quality in fresh produce supply chains | Mixed-method study, including interviews (31 participants), company data, and lab sensory tests on seven items | Australia | Tomatoes, mushrooms, berries, leafy greens, cucumbers, lettuce, bananas, apples, pears | Packaging extended shelf-life and maintained sensory quality; reduced handling damage and waste; improved product appeal and transport efficiency | Design packaging to enhance cold chain integration and consumer education; prioritize functionality (e.g., resealability, protection, visibility) to reduce waste |