From Control to Incentive: How Market-Driven Environmental Regulation Shapes ESG Performance in Manufacturing Industries

Abstract

1. Introduction

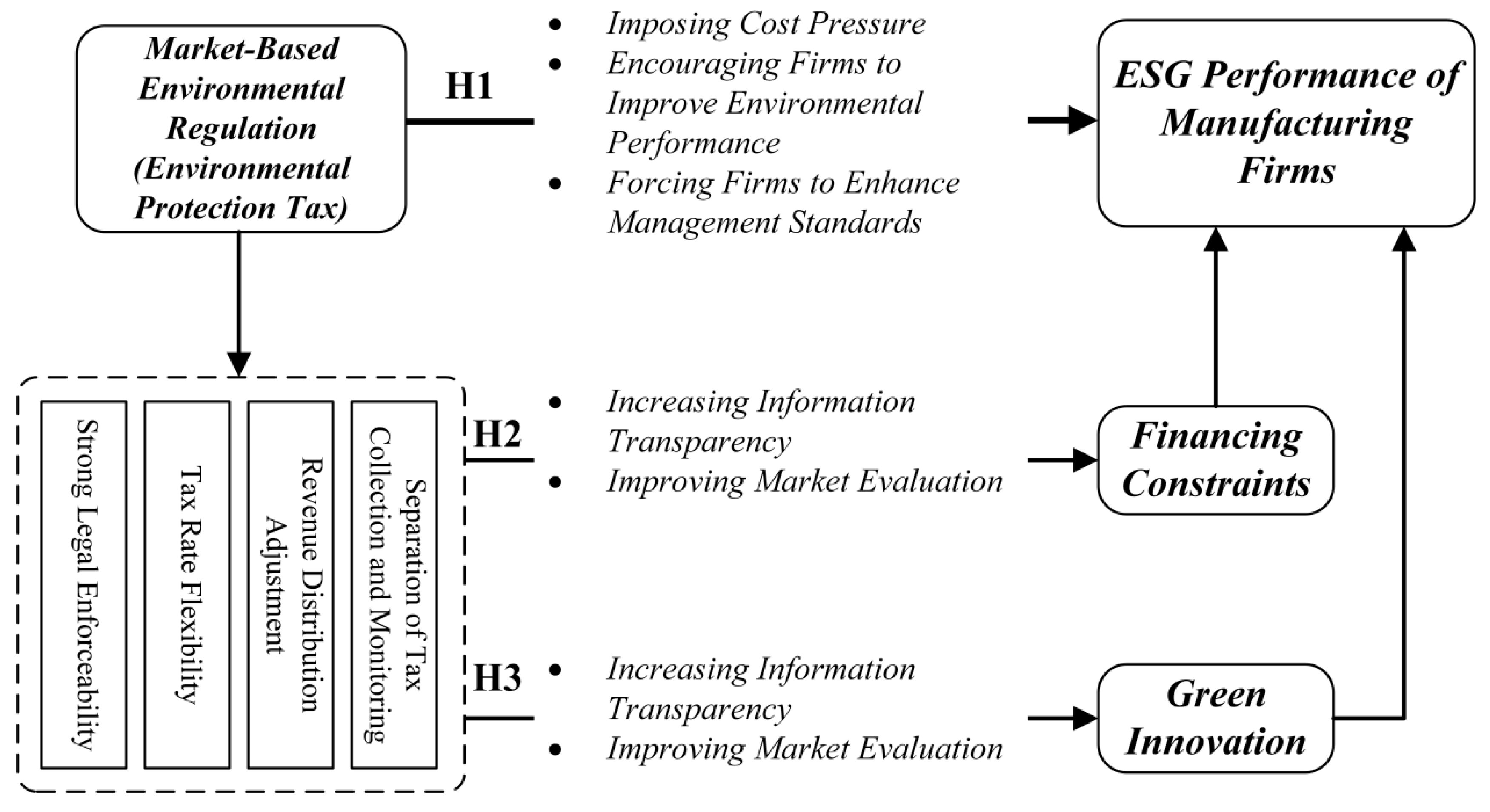

2. Institutional Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Institutional Background

2.2. Research Hypothesis

3. Research Design

3.1. Model

3.1.1. Difference-in-Differences Model

3.1.2. Mediator Effect Model

3.2. Variable Selection and the Source of the Data

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Control Variable

3.2.4. Mediator Variables

| Name | Abbreviation | Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Manufacturing Firm ESG Performance | MFESG | ESG rating of listed companies |

| Independent Variable | Environmental Protection Tax | EPT | The variable takes the value 1 if the applicable tax rate on water pollutants under the Environmental Protection Tax is increased in the firm’s registered location, and 0 otherwise. |

| Control Variables | Firm Size | SIZE | Natural logarithm of total assets |

| Debt-to-Asset Ratio | LEV | Total liabilities/Total assets | |

| Return on Assets | ROA | Net profit/Total assets | |

| Cash Flow Ratio | CF | Net cash flow from operating activities/Total assets | |

| Revenue Growth Rate | GROW | This year’s revenue/Last year’s revenue − 1 | |

| Proportion of Shares Held by Top Five Shareholders | TOP5 | Number of shares held by the top five shareholders/Total shares | |

| CEO Duality | DUAL | Set to 1 if the chairman and CEO are the same person, otherwise set to 0 | |

| Fixed Asset Ratio | FIXED | Net fixed assets/Total assets | |

| Firm Age | FA | Ln (Number of years since the firm was established + 1) | |

| Mediator Variables | Financing Constraints | WW | Calculated using Whited and Wu’s method [40] |

| Green Innovation | GI | ln (Sum of granted green invention patents and utility model patents) |

3.2.5. Sample Selection and Data Sources

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Benchmark Regression Analysis

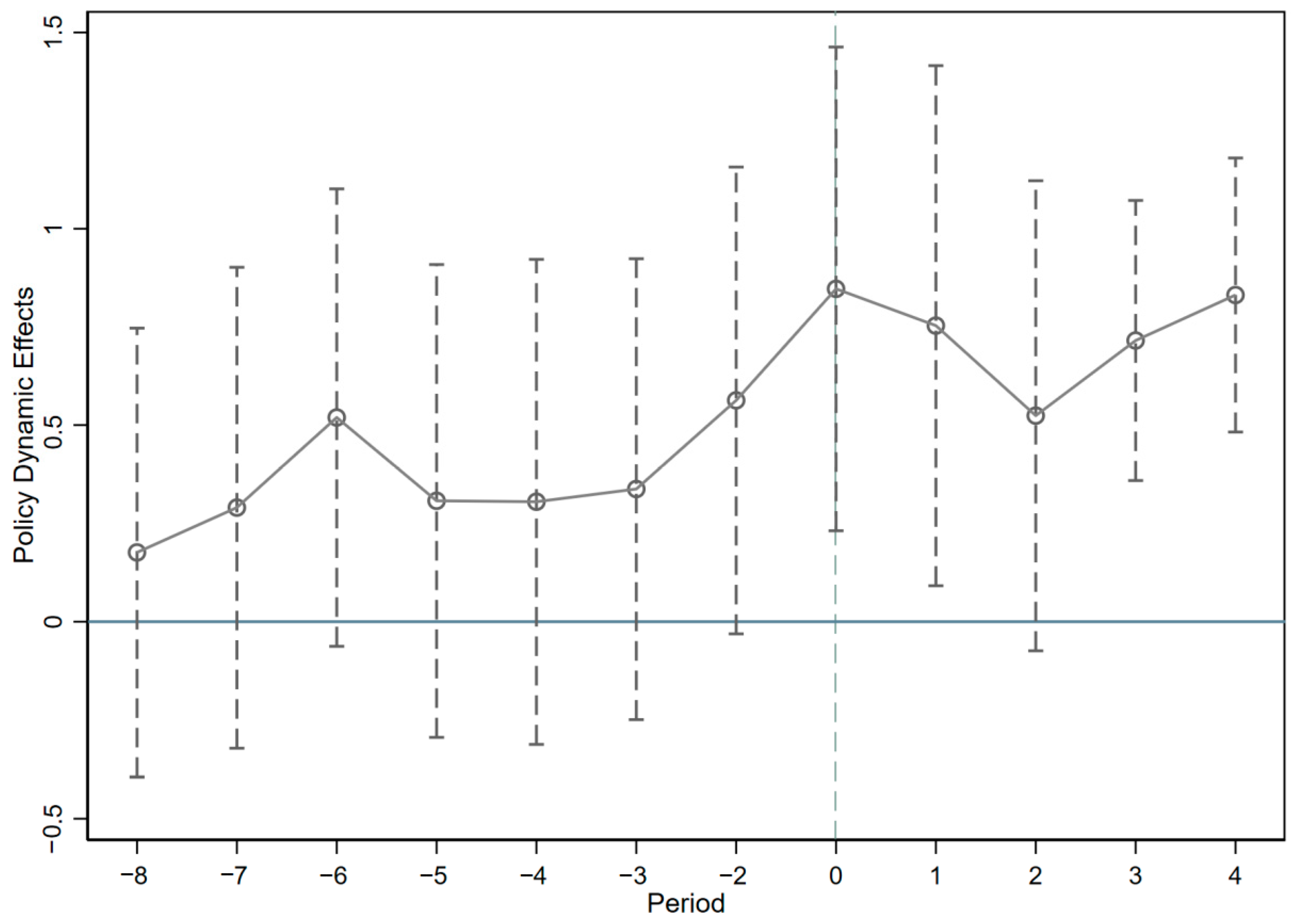

4.2. Parallel Trend Test

4.3. Robustness Test

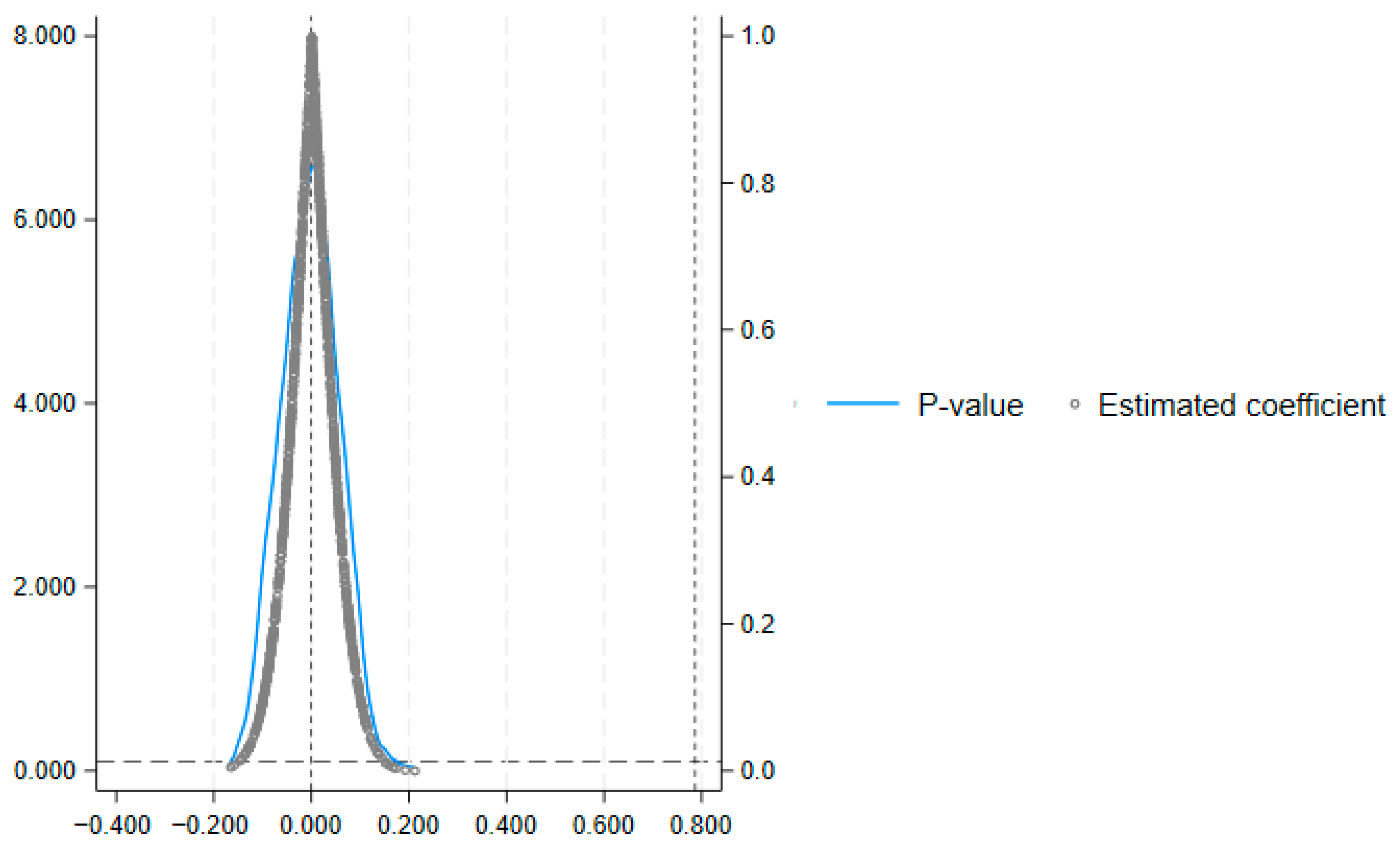

4.3.1. Placebo Test

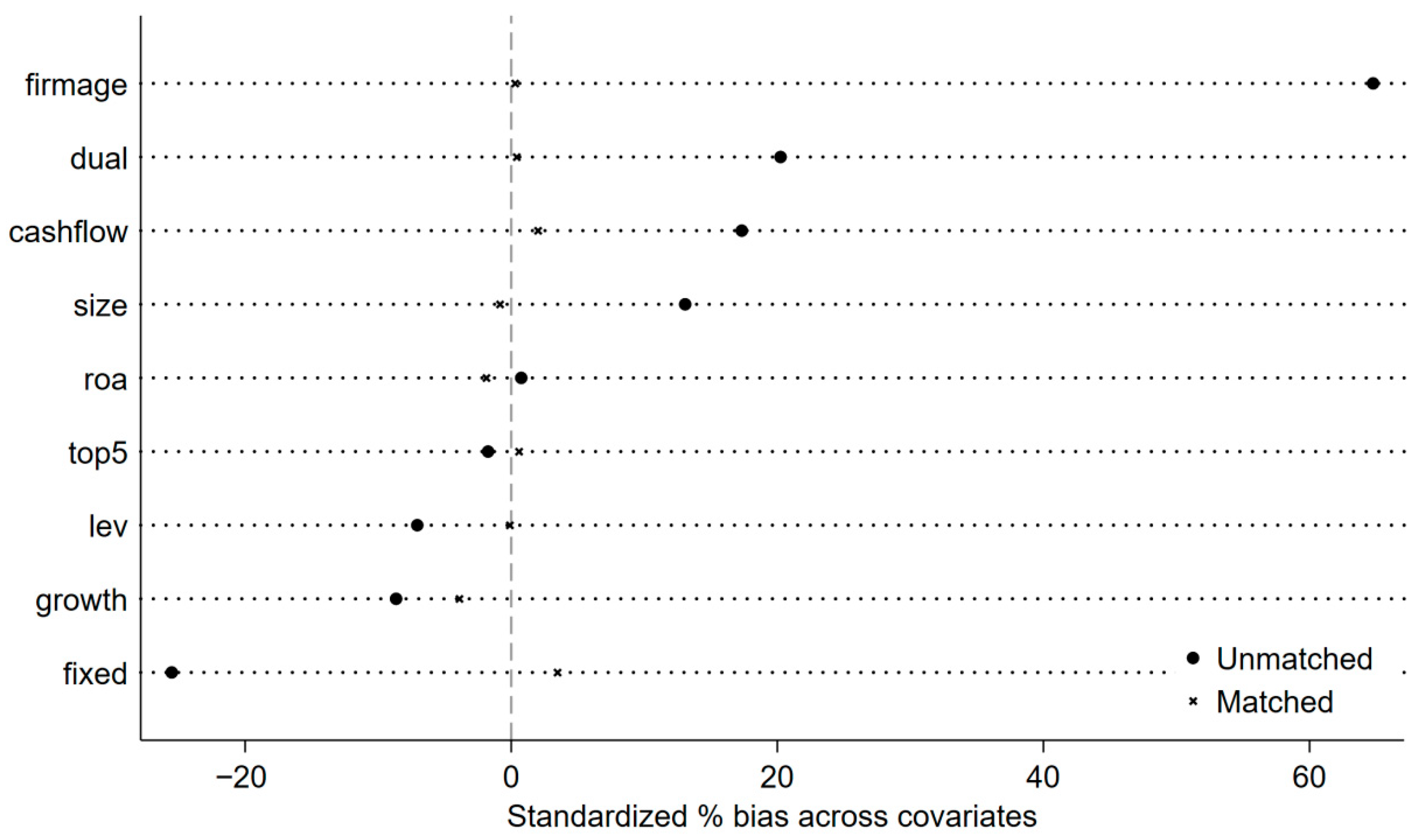

4.3.2. PSM-DID

4.3.3. Exclusion of Other Competing Hypotheses

4.3.4. Alternative ESG Measurement

4.3.5. Alternative Measurement of Environmental Protection Tax

4.3.6. Shortening the Sample Period

4.3.7. Wild-Cluster Bootstrap with Province-Level Clustering

4.3.8. Robustness Test Using Industry-Year Standardized ESG Scores

4.3.9. Addressing Omitted Variable Concerns

4.3.10. Endogeneity and Caveats

4.4. Mechanism Analysis

4.4.1. Financing Constraints

4.4.2. Green Innovation

5. Further Analysis

5.1. The ESG Dimension Decomposition

5.2. Analysis of Heterogeneity

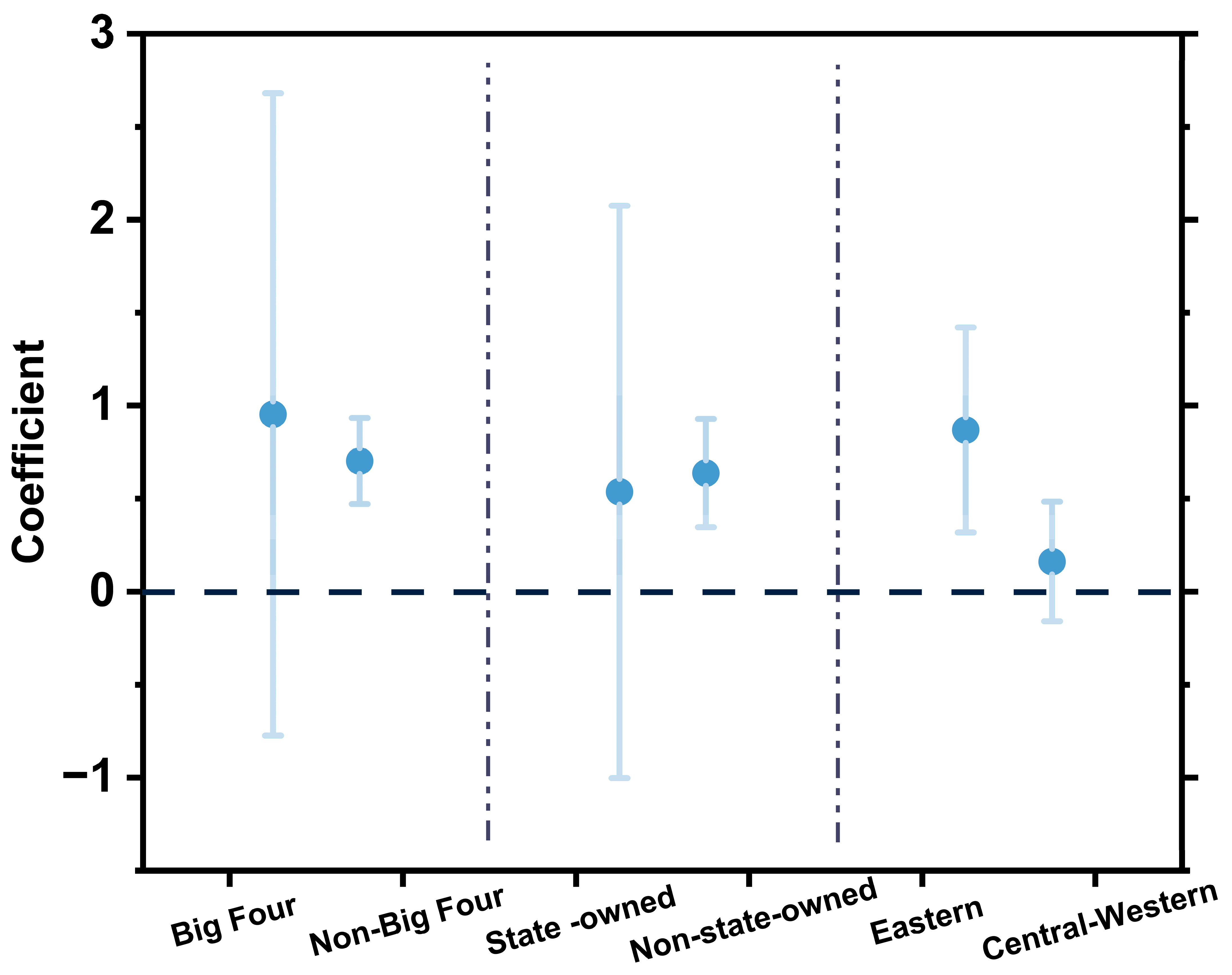

5.2.1. Have They Been Audited by the Big Four

5.2.2. Ownership Type

5.2.3. Geographical Location

5.2.4. Discussion of Heterogeneity Results

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Comparison of Sewage Fee and Environmental Tax by Province in China

| Province | Atmospheric Pollutants | Water Pollutants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sewage Fee | Environmental Protection Tax | Sewage Fee | Environmental Protection Tax | |

| Beijing | Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides 10 | 12 | COD 10, ammonia nitrogen 12 | 14 |

| Tianjin | Sulfur dioxide 6.30, nitrogen oxides 8.50 | 10 | COD 7.50, ammonia nitrogen 9.50 | 12 |

| Hebei | 2.4 | Primary pollutant 9.6 and other pollutants 4.8; Secondary pollutant 6 and other pollutants 4.8; Tertiary pollutant 4.8 | 2.8 | Primary pollutant 9.6 and other pollutants 4.8; Secondary pollutant 6 and other pollutants 4.8; Tertiary pollutant 4.8 |

| Shanghai | Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides 4 | 2018: Sulfur dioxide 6.65, nitrogen oxides 7.6, other pollutants 1.2; 2019: | COD, ammonia 3 | COD, ammonia nitrogen 4.8, Class I water pollutants 1.4, others 1.4 |

| Shandong | Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides 6, other 1.2 | Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides 6, other pollutants 1.2 | COD, ammonia nitrogen and five heavy metals 1.4 | COD, ammonia nitrogen and five heavy metals3, other pollutants 1.4 |

| Jiangsu | 3.6 | Nanjing 8.4, Wuxi, Changzhou, Suzhou, Zhenjiang 6, other areas 4.8 | 4.2 | Nanjing 8.4, Wuxi, Changzhou, Suzhou, Zhenjiang 7, other areas 5.6 |

| Zhejiang | 1.2 | Four heavy metal pollutants 1.8, other pollutants 1.2 | 1.4 | Five heavy metals, COD and ammonia nitrogen 1.8, other pollutants 1.4 |

| Sichuan | 1.2 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| Shanxi | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| Hunan | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 3 |

| Henan | 1.2 | 4.8 | 1.4 | 5.6 |

| Guizhou, Hainan | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| Guangdong, Guangxi | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| Tibet | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| Chongqing | 1.2 | 2018–2020: 2.4, 2021: 3.5 | 1.4 | 2018–2020: 3, 2021: 3 |

| Fujian | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.4 | Five heavy metals, COD and ammonia nitrogen 1.5, other pollutants 1.4 |

| Hubei | 2.4 | Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides 2.4, other pollutants 1.2 | 2.8 | Five heavy metals, COD, total phosphorus, ammonia nitrogen 2.8, other pollutants 1.4 |

| Anhui | 1.2 | 1.2 | Five heavy metals, COD and ammonia nitrogen 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Heilongjiang, Liaoning, Jilin, Jiangxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Ningxia, Xinjiang | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Yunnan | 1.2 | 2018: 1.2, 2019: 2.8 | 1.4 | 2018: 1.4, 2019: 3.5 |

| Inner Mongolia | Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides 1.2 | 2018: 1.2, 2019: 1.8, 2020: 2.4 | 1.4 | 2018: 1.4, 2019: 3.5 |

References

- Zhang, C.; Fang, J.; Ge, S.; Sun, G. Research on the Impact of Enterprise Digital Transformation on Carbon Emissions in the Manufacturing Industry. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 92, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, L.; Peng, L.; Zhou, H.; Hu, F. Enterprise Pollution Reduction through Digital Transformation? Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chu, E. Shifting Focus from End-of-Pipe Treatment to Source Control: ESG Ratings’ Impact on Corporate Green Innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, C. Regional Digitalization and Corporate ESG Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 473, 143503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, S. Supply Chain Resilience, ESG Performance, and Corporate Growth. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 97, 103763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Shang, M.; Huang, Y. Corporate Culture and ESG Performance: Empirical Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Feng, C.; Mirza, S.S.; Ahsan, T.; Qureshi, M.A. How Uncertainty Can Determine Corporate ESG Performance? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 2290–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Klein, T.; Ren, Y.-S.; Duong, D. Global Geopolitical Risk and Corporate ESG Performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Guo, X.; Yue, P. Media Coverage and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Investor Attention and Corporate ESG Performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 60, 104887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Jia, Z.; Yang, S. Exploring FinTech, Green Finance, and ESG Performance across Corporate Life-Cycles. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 97, 103871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Wang, H.; Bai, C. Local Green Finance Policies and Corporate ESG Performance. Int. Rev. Financ. 2023, 23, 721–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Shi, Y.; Zheng, J. Can Green Credit Policies Improve Corporate ESG Performance? Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 2678–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Richardson-Barlow, C.; Fan, L.; Cai, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z. Towards Organic Collaborative Governance for a More Sustainable Environment. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Sun, X. Environmental Protection Tax and Green Low-Carbon Development. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 86, 108366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Rahbarimanesh, A. The Impact of Environmental Protection Tax on Green Innovation of Heavily Polluting Enterprises in China: A Mediating Role Based on ESG Performance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Chen, X.; Wen, H. How Does Environmental Protection Tax Affect Corporate Environmental Investment? Sustainability 2022, 14, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigou, A. The Economics of Welfare; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S. Environmental Protection Tax, Green Innovation, and ESG Performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 65, 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Zhou, Z.; Jin, D. Impact of Environmental Protection Tax on Carbon Intensity in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 29695–29718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Jing, Q.; Chen, H. The Impact of Environmental Tax Laws on Heavy-Polluting Enterprise ESG Performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, X. Can Green Finance Improve Corporate ESG Performance? Empirical evidence from Chinese A-share listed companies. Asia-Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2025, 32, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.; Zhao, J. Demand for Green Finance. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, Y.-S.; Narayan, S.; Huynh, N.Q.A. Does Climate Risk Impact ESG Performance? Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, L.; Behera, B.; Sethi, N. Do Green Finance and Green Technology Innovation Improve Sustainability? Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 2709–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment–Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, W. Impact of Regional Finance Reform and Innovation Policies on Green Innovation in Pilot Cities. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 888–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.C.; Larcker, D.F.; Wang, C.C.Y. Staggered Difference-in-Differences Estimates. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 144, 370–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, D.; Krueger, A.B. Minimum Wages and Employment. Am. Econ. Rev. 1994, 84, 772–793. [Google Scholar]

- Imbens, G.W.; Wooldridge, J.M. Recent Developments in Program Evaluation. J. Econ. Lit. 2009, 47, 5–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Bank Deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhong, S.; Gao, W. Impact of Legal Commitments on Carbon Intensity. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, C.; Tu, Y.; Li, Z. Enterprise Digital Transformation and ESG Performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Hua, G.; Huo, B. Green Finance Policies, Financing Constraints and ESG Performance. Oper. Manag. Res. 2024, 17, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Goh, M.; Wang, Y. Executive Green Cognition and ESG Performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 69, 106271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzari, S.M.; Hubbard, R.G.; Petersen, B.C. Financing Constraints and Corporate Investment; Brookings Papers on Economic Activity; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 141–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S.N.; Zingales, L. Investment–Cash Flow Sensitivities. Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 169–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, S. Firm Investment and Financial Status. J. Financ. 1999, 54, 673–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whited, T.M.; Wu, G. Financial Constraints Risk. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2006, 19, 531–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J. Does Flattening Government Improve Economic Performance? J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 123, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhong, J. Smart City Construction Policies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 122003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, B.; Sant’Anna, P.H.C. Difference-in-Differences with Multiple Time Periods. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Ferrara, E.; Chong, A.; Duryea, S. Soap Operas and Fertility: Evidence from Brazil. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2012, 4, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehejia, R.H.; Wahba, S. Causal Effects in Nonexperimental Studies. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999, 94, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Xie, Z.; Li, Z. Environmental Pollution Liability Insurance. Energy Policy 2022, 171, 113267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. Propensity Score in Observational Studies. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, E. Unobservable Selection and Coefficient Stability: Theory and Evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2019, 37, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, M.; Merkley, K.J.; Silva, F.B.G. Government Guarantees and Banks’ Income Smoothing. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2023, 63, 123–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, K.; Keele, L.; Tingley, D. Causal Mediation Analysis. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; He, Y. Green Financial System and ESG. Energy Econ. 2024, 130, 107287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; He, Y.; Zeng, L. Can Green Finance Improve ESG Performance? Evidence from green credit policy in China. Energy Econ. 2024, 137, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFESG | 20,971 | 73.19 | 4.573 | 59.60 | 83.40 | Listed Company ESG Rating Database |

| EPT | 20,971 | 0.445 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 | China Government Website |

| SIZE | 20,971 | 22.01 | 1.169 | 19.98 | 25.60 | CSMAR Database |

| LEV | 20,971 | 0.383 | 0.194 | 0.0550 | 0.864 | |

| ROA | 20,971 | 0.0490 | 0.0620 | −0.169 | 0.214 | |

| CF | 20,971 | 0.0490 | 0.0660 | −0.134 | 0.228 | |

| GROW | 20,971 | 0.168 | 0.331 | −0.464 | 1.740 | |

| TOP5 | 20,971 | 0.537 | 0.149 | 0.212 | 0.864 | |

| DUAL | 20,971 | 0.320 | 0.467 | 0 | 1 | |

| FIXED | 20,971 | 0.216 | 0.132 | 0.0150 | 0.611 | |

| FA | 20,971 | 2.883 | 0.333 | 1.792 | 3.497 | |

| WW | 17,622 | −1.012 | 0.0670 | −1.198 | −0.863 | |

| GI | 20,971 | 0.333 | 0.694 | 0 | 3.296 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFESG | MFESG | MFESG | MFESG | |

| EPT | 0.7828 *** | 0.6882 *** | 0.6767 *** | 0.6549 *** |

| (3.7335) | (3.7628) | (3.9901) | (3.9552) | |

| SIZE | 1.1210 *** | 1.1122 *** | 1.1331 *** | |

| (13.1536) | (12.9568) | (12.5546) | ||

| LEV | −4.8142 *** | −4.2876 *** | −4.1724 *** | |

| (−11.8485) | (−10.4631) | (−10.0047) | ||

| ROA | 12.7801 *** | 13.8259 *** | 13.9686 *** | |

| (13.2847) | (14.2506) | (13.0752) | ||

| CF | −1.0190 | −1.0989 * | ||

| (−1.5372) | (−1.9117) | |||

| GROW | −0.8989 *** | −0.9617 *** | ||

| (−6.7147) | (−7.4598) | |||

| TOP5 | 2.4346 *** | 2.1317 *** | ||

| (7.2230) | (6.0235) | |||

| DUAL | 0.0433 | |||

| (0.4655) | ||||

| FIXED | 0.4588 | |||

| (0.5800) | ||||

| FA | −0.8059 *** | |||

| (−3.7618) | ||||

| _cons | 72.8440 *** | 49.4258 *** | 48.2679 *** | 50.1513 *** |

| (781.1409) | (27.1311) | (27.4379) | (28.1933) | |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Stkcd FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province#Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 20963 | 20962 | 20957 | 20957 |

| R2 | 0.0702 | 0.1838 | 0.1928 | 0.1954 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSM-DID | Smart | BBC | Innovation | |

| EPT | 0.6599 *** | 0.7819 *** | 1.0240 *** | 0.6034 *** |

| (3.9912) | (3.2991) | (3.7751) | (4.0494) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Stkcd FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province#Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 17,727 | 12,448 | 6571 | 6736 |

| R2 | 0.1960 | 0.2109 | 0.2159 | 0.2508 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFESG_Hua Zheng | MFESG | Shorten the Sample Interval | Wild-Cluster Bootstrap | ESG_z (Industry–Year Standardized | |

| EPT | 0.1387 *** | 0.7703 *** | 0.6549 *** | 0.141 ** | |

| (3.8327) | (3.4342) | (2.9826) | (2.1153) | ||

| EPT_a | 0.1352 *** | ||||

| (3.2712) | |||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Stkcd FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province#Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 20957 | 20957 | 13624 | 20957 | 20957 |

| R2 | 0.1808 | 0.1941 | 0.1675 | 0.1954 | 0.3172 |

| Model | Fixed Effects Included | Coefficient on EPT | R2 | Rmax | δ (Relative Strength of Unobserved Selection) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Baseline OLS | None | 0.421 | 0.071 | — | — | — |

| (2) Main DID Model | Year + Industry FE | 0.655 | 0.194 | — | — | Main estimated effect |

| (3) Oster Bound (Rmax = 1.3R2) | Same as (2) | 0.618 | 0.194 → 0.252 | 0.252 | δ = 2.87 | Effect remains positive; robust to omitted variables |

| (4) Oster Bound (Rmax = 2R2) | Same as (2) | 0.601 | 0.194 → 0.388 | 0.388 | δ = 3.94 | Stronger robustness under more conservative bound |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFESG | WW | MFESG | GI | MFESG | E | S | G | |

| EPT | 0.6579 *** | −0.0020 *** | 0.7514 *** | 0.0911 ** | 0.5998 *** | 0.7524 ** | 0.6181 ** | 0.4986 * |

| (3.9552) | (−3.6180) | (4.0873) | (2.3468) | (3.6483) | (2.5668) | (2.2165) | (1.9846) | |

| WW | −0.6126 *** | |||||||

| (−3.1234) | ||||||||

| GI | 0.6376 *** | 0.9751 *** | 0.8621 *** | 0.3272 ** | ||||

| (5.6318) | (6.7667) | (5.5078) | (2.4141) | |||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Stkcd FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province#Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 20957 | 17614 | 17614 | 20957 | 20957 | 20957 | 20957 | 20957 |

| R2 | 0.1954 | 0.8766 | 0.2145 | 0.1791 | 0.2030 | 0.2447 | 0.2027 | 0.2227 |

| Sobel Z | 3.125 *** | 2.984 *** | 2.137 ** | 3.218 *** | 2.129 ** |

| Effect | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Mediator: Financing Constraints | |||

| ACME (Indirect Effect) | 0.00047 | [0.00016, 0.00082] | 0.002 |

| ADE (Direct Effect) | 0.65443 | [0.482, 0.827] | 0 |

| Total Effect | 0.6549 | [0.481, 0.829] | 0 |

| Mediated Proportion (ACME/Total) | 0.07% | — | — |

| Panel B. Mediator: Green Innovation | |||

| ACME (Indirect Effect) | 0.0573 | [0.023, 0.101] | 0.001 |

| ADE (Direct Effect) | 0.5976 | [0.414, 0.771] | 0 |

| Total Effect | 0.6549 | [0.481, 0.829] | 0 |

| Mediated Proportion (ACME/Total) | 8.75% | — | — |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E Score | S Score | G Score | |

| EPT | 0.8413 *** | 0.6966 ** | 0.5284 |

| (3.0489) | (2.3488) | (1.5957) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Stkcd FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Province#Year FE | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 20957 | 20957 | 20957 |

| R2 | 0.2372 | 0.1986 | 0.2216 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Four | Non-Big Four | State-Owned | Non-State-Owned | Eastern | Central-Western | |

| EPT | 0.9324 | 0.7132 *** | 0.5321 | 0.6341 *** | 0.8312 *** | 0.1313 |

| (1.2314) | (3.2313) | (0.9830) | (3.5328) | (3.2910) | (0.7728) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Stkcd FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province#Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 986 | 19897 | 6043 | 14440 | 14532 | 6388 |

| R2 | 0.4001 | 0.1892 | 0.2489 | 0.2042 | 0.2034 | 0.2197 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Zhong, S. From Control to Incentive: How Market-Driven Environmental Regulation Shapes ESG Performance in Manufacturing Industries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310516

Zhang W, Zhong S. From Control to Incentive: How Market-Driven Environmental Regulation Shapes ESG Performance in Manufacturing Industries. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310516

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wei, and Shen Zhong. 2025. "From Control to Incentive: How Market-Driven Environmental Regulation Shapes ESG Performance in Manufacturing Industries" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310516

APA StyleZhang, W., & Zhong, S. (2025). From Control to Incentive: How Market-Driven Environmental Regulation Shapes ESG Performance in Manufacturing Industries. Sustainability, 17(23), 10516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310516