GHG Accounting and Gendered Carbon Accountability in a Shipping Agency: A Single-Case Study with Ethnographic Elements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Carbon Accounting and Accountability in Maritime Sustainability

2.2. Digitalization, Innovation, and the Transformation of Accountability

2.3. Gender Equality and Carbon Accountability

2.4. Toward a Gender-Inclusive Accountability Framework in Maritime Agencies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Selection and Context

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Insider–Outsider Dynamics and Reflexivity

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Research Quality

4. Results

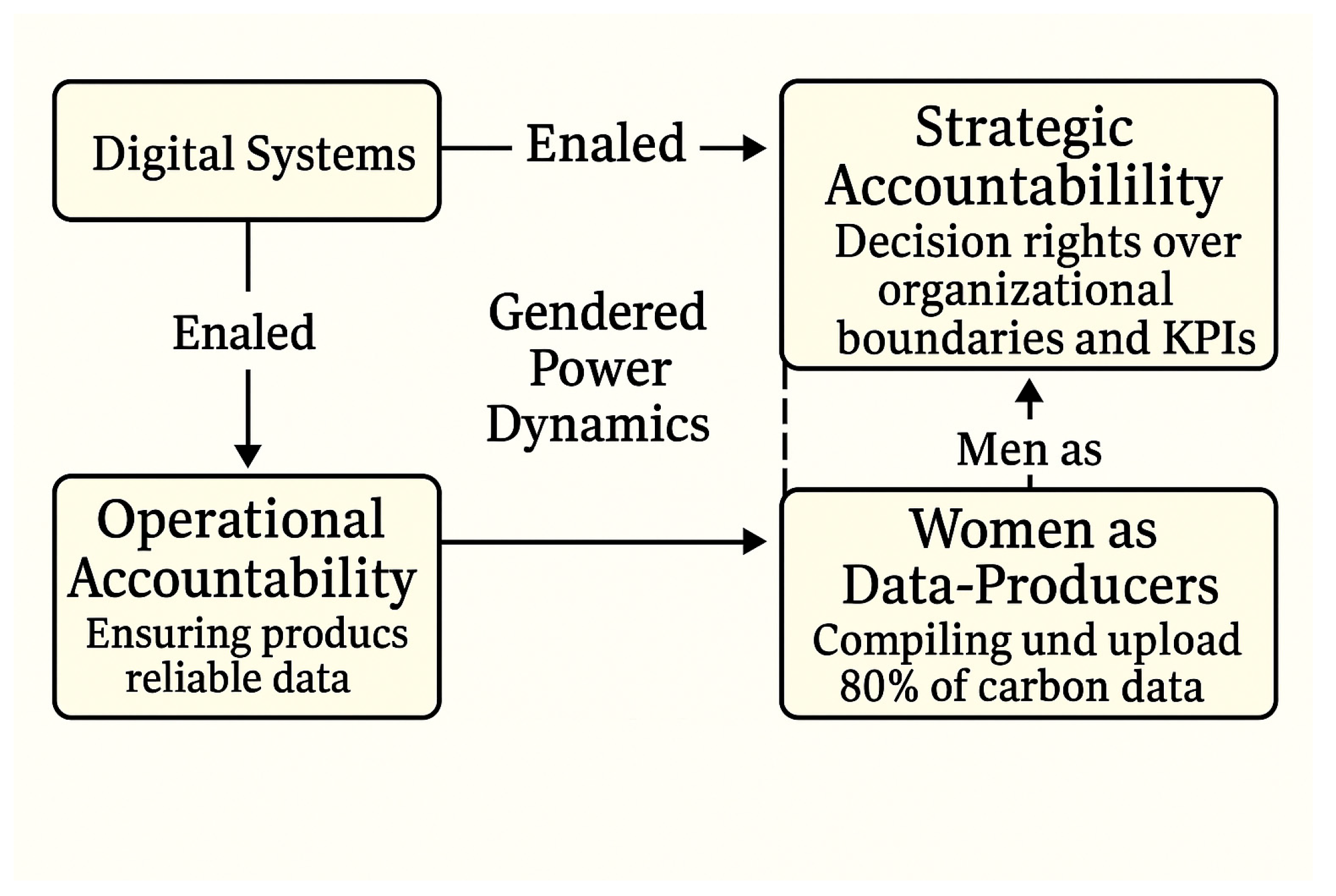

4.1. Digital Systems as Structural Enablers

“With TeamSystem Enterprise I can control each aspect at any time and everywhere. Before, reconciling bills and invoices required days; now it takes hours”.

“We can tell you how many bookings we handle or how much energy we consume in the office, but we don’t know how the forwarders calculate their emissions. That’s outside our reach”.

4.2. Women as Data Producers

“The choice of a female CFO and an entirely female accounting department is not entirely accidental. In our experience, women are more responsible for accounting management, and they also show greater flexibility in learning the features of digital technologies.”

“When the software house releases new functions, we watch the video tutorials and test them ourselves. We don’t need external trainers anymore.”

4.3. Men as Strategic Decision-Makers

“I once suggested we include suppliers’ emissions in our reporting. The idea was appreciated, but then the matter was dropped. In the end, it was not considered a priority.”

“The girls in accounting are precise and reliable, but when it comes to deciding how to deal with the shipowner or which reports matter, that’s something we decide at the top.”

4.4. Evolution of Accountability Practices Under External Pressures

“Every month, the shipowner stresses us to complete Hyperion reports within the deadline. Sometimes we stay late to finish everything. It is exhausting.”

“Sustainability is important, but we must be pragmatic. We follow what the shipowner requires and what the authorities ask for. Going beyond that would require resources we do not have.”

5. Discussion

5.1. Gendered Organizations: Women as Producers of Data, Men as Producers of Priorities

5.2. From Capability to Accountability: A Socio-Technical Mechanism

5.3. Advancing Knowledge: Theoretical, Empirical, and Methodological Contributions and Policy Implications for the Industry

- Governance of the carbon data pipeline.

- 2.

- Scope 3 engagement.

- 3.

- Capacity-building and participatory design.

- 4.

- Assurance and incentives.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharmina, M.; Edelenbosch, O.Y.; Wilson, C.; Freeman, R.; Gernaat, D.E.H.J.; Gilbert, P.; Larkin, A.; Littleton, E.W.; Traut, M.; van Vuuren, D.P.; et al. Decarbonising the critical sectors of aviation, shipping, road freight and industry to limit warming to 1.5–2 °C. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notteboom, T.E.; Winkelmans, W. Structural changes in logistics: How will port authorities face the challenge? Marit. Policy Manag. 2001, 28, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C.; Marlow, P.B.; Lu, C.S. Assessing resources, logistics service capabilities, innovation capabilities and the performance of container shipping services in Taiwan. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 122, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P.H.; Liao, C.H. Supply chain integration, information technology, market orientation and firm performance in container shipping firms. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2015, 26, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J. Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gend. Soc. 1990, 4, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J. Inequality regimes: Gender, class, and race in organizations. Gend. Soc. 2006, 20, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.J. (En)gendering sustainability. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 26, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Romi, A.M.; Senkl, D. Accounting, sustainability and the feminine. In Handbook of Accounting and Sustainability; Adams, C.A., Larrinaga, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. The social accounting project and Accounting Organizations and Society: Privileging engagement, imaginings, new accountings and pragmatism over critique? Account. Organ. Soc. 2002, 27, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Advancing research into accounting and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020, 33, 1657–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. Accounting and sustainability: An introduction. In Handbook of Accounting and Sustainability; Adams, C.A., Larrinaga, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Luo, L.; Shamsuddin, A.; Tang, Q. Corporate carbon accounting: A literature review of carbon accounting research from the Kyoto Protocol to the Paris Agreement. Account. Financ. 2022, 62, 261–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascui, F.; Lovell, H. As frames collide: Making sense of carbon accounting. Account. Audit. Account. 2011, 24, 978–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M.; Di Vaio, A.; Hassan, R.; Palladino, R. Digitalization and new technologies for sustainable business models at the ship–port interface: A bibliometric analysis. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 49, 410–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirzka, C.; Acciaro, M. Principal–agent problems in decarbonizing container shipping: A panel data analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 98, 102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1506336169. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, L.; Vavrus, F. Rethinking Case Study Research: A Comparative Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781315674886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siggelkow, N. Persuasion with Case Studies. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Lawson, E.T.; Raditloaneng, W.N.; Solomon, D.; Angula, M.N. Gendered vulnerabilities to climate change: Insights from the semi-arid regions of Africa and Asia. Clim. Dev. 2019, 11, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Gender and Climate Action; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; Available online: https://www.unep.org/topics/gender/gender-and-climate-action (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Di Vaio, A.; Zaffar, A.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Garofalo, A. Decarbonization technology responsibility to gender equality in the shipping industry: A systematic literature review and new avenues ahead. J. Shipp. Trade 2023, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Zaffar, A.; Chhabra, M.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Carbon accounting and integrated reporting for net-zero business models towards sustainable development: A systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 7216–7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, M.; Tregidga, H.; Unerman, J. Sustainability Accounting and Accountability; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S. Linking environmental management accounting: A reflection on (missing) links to sustainability and planetary boundaries. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2018, 38, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, T.; Chapman, C.S. Doing qualitative field research in management accounting: Positioning data to contribute to theory. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. The possibilities of accountability. Account. Organ. Soc. 1991, 16, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Maritime Forum. Diversifying Maritime Leadership; Global Maritime Forum: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023; Available online: https://globalmaritimeforum.org (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Carroll, A.B.; Brown, J.A. Corporate social responsibility: A review of current concepts, research, and issues. In Corporate Social Responsibility; Carroll, A.B., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.Y.; Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F. Sustainable shipping management: Definitions, critical success factors, drivers and performance. Transp. Policy 2023, 141, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasoulis, I. Advancing aspects of social sustainability dimension in shipping: Exploring the role of corporate social responsibility in supporting the Seafarer Human Sustainability Declaration framework. Aust. J. Marit. Ocean Aff. 2023, 15, 518–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaraftis, H.N. Decarbonization of maritime transport: To be or not to be? Marit. Econ. Logist. 2019, 21, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettler, M.; Graf-Vlachy, L. Corporate scope 3 carbon emission reporting as an enabler of supply chain decarbonization: A systematic review and comprehensive research agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 33, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Laine, M.; Roberts, R.W.; Rodrigue, M. Organized hypocrisy, organizational façades, and sustainability reporting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2015, 40, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, C.K.; Bhat, M.A.; Alshabibi, B.; Al Balushi, Z.S.; Pal, A. Mapping four decades of research on sustainability accounting, sustainable finance, and governance: A bibliometric analysis and future directions. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2025. article ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeil, A.; Ghosh, S. Gender imbalance in the maritime industry: Impediments, initiatives and recommendations. Aust. J. Marit. Ocean Aff. 2017, 9, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, M. Gender and work within the maritime sector. In Women, Work and Transport; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022; pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vaio, A.; Hassan, R.; Palladino, R. Blockchain technology and gender equality: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 68, 102517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, T.; Dent, J.F. Accounting and organizations: Realizing the richness of field research. J. Manag. Account. Res. 1998, 10, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.; Dillard, J.; Hopper, T. Accounting, accountants and accountability regimes in pluralistic societies: Taking multiple perspectives seriously. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 626–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.K.; Varshney, Y.; Awasthi, R.K.; Pratap, M.; Yadav, S.K.; Kumar, M. Digital Transformation and Its Environmental Implications in Supply Chain Management. J. Big Data Anal. Bus. Intell. 2025, 2, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Valentinetti, D.; Rea, M.A. Factors influencing the digitalization of sustainability accounting, reporting and disclosure: A systematic literature review. Meditari Account. Res. 2025, 33, 633–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, D.; Saliterer, I.; Steccolini, I. Digitalization, accounting and accountability: A literature review and reflections on future research in public services. Financ. Account. Manag. 2022, 38, 152–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouya, A.; Samiolo, R. Performance measurement in global governance: Ranking and the politics of variability. Account. Organ. Soc. 2016, 55, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J.; Kirkham, L. Glass ceilings, glass cliffs or new worlds? Revisiting gender and accounting. Account. Audit. Account. 2008, 21, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, K. Accounting as gendering and gendered: A review of 25 years of critical accounting research on gender. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2017, 43, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambrin, C.; Lambert, C. Who is she and who are we? A reflexive journey in research on women in accounting. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2012, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlif, H.; Achek, I. Gender in accounting research: A review. Manag. Audit. J. 2017, 32, 627–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, L.; Loft, A. Gender and the construction of the professional accountant. Account. Organ. Soc. 1993, 18, 507–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, A.; Occhipinti, Z.; Verona, R. The consideration of diversity in the accounting literature: A systematic literature review. Eur. Account. Rev. 2024, 33, 1667–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehnaz, L.; Yang, C. Women in accounting research: A review of gender diversity, equity and inclusion. Meditari Account. Res. 2025, 33, 30–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, A.C.; Kim, A. Gender gap truth battles: Conceptualising and analysing statement forms in annual reports. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2025, 38, 1662–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B.; Romero, S.; Ruiz-Blanco, S. Women on Boards: Do They Affect Sustainability Reporting? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewo, B.; Moses, O.; Orazalin, N. Board Gender Diversity and Carbon Trade Finance: Evidence from Multinational Corporations on the Role of Institutional Quality and Cultural Environment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 4165–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muktadir-Al-Mukit, D.; Bhaiyat, F.H. Impact of corporate governance diversity on carbon emission under environmental policy via the mandatory nonfinancial reporting regulation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1397–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro-Gen, M.; Lozano, R.; Carpenter, A. Gender equality for sustainability in ports: Developing a framework. Mar. Policy 2021, 131, 104593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.C.; Emad, G.R.; Fei, J. Key factors impacting women seafarers’ participation in the evolving workplace: A qualitative exploration. Mar. Policy 2023, 148, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampone, G.; Nicolò, G.; Sannino, G.; De Iorio, S. Gender diversity and SDG disclosure: The mediating role of the sustainability committee. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2024, 25, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.; Panayiotou, A.; Dimou, A.; Katsifaraki, G. Gender and environmental sustainability: A longitudinal analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroulakis, P.J.; Papadimitriou, S.; Tsirikou, F. Gender perceptions in shipping. Aust. J. Marit. Ocean Aff. 2024, 16, 238–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, J.S.; Bohler-Muller, N. Counting women? Gendered sustainability and inclusiveness for an ocean accounting framework. J. Indian Ocean Reg. 2024, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Chhabra, M.; Zaffar, A.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Accounting and accountability in the transition to zero-carbon energy for climate change: A systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 5925–5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, C. Ethnography, ethnomethodology and anthropology studies in accounting. In The Routledge Companion to Qualitative Accounting Research Methods; Hoque, Z., Parker, L.D., Covaleski, M.A., Haynes, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.J.; Morgan, W. Case study research in accounting. Account. Horiz. 2008, 22, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C. When ethnography meets scientific aspiration: A comparative exploration of ethnography in anthropology and accounting. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2025, 22, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maanen, J. Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, M.; Atkinson, P. Ethnography: Principles in Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harwati, L.N. Ethnographic and case study approaches: Philosophical and methodological analysis. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2019, 7, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angers, J.; Machtmes, K. An ethnographic-case study of beliefs, context factors, and practices of teachers integrating technology. Qual. Rep. 2005, 10, 771–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, P.I.; Fusch, G.E.; Ness, L.R. How to conduct a mini-ethnographic case study: A guide for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2017, 22, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Kärreman, D. Constructing Mystery: Empirical Matters in Theory Development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1265–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybema, S.; Keenoy, T.; Oswick, C.; Beverungen, A.; Ellis, N.; Sabelis, I. Articulating Identities. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, A.L. Retelling Tales of the Field: In Search of Organizational Ethnography 20 Years On. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyta, P.; Malsch, B. Ethnographic accounting research: Field notes from the frontier. Account. Perspect. 2018, 17, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Sköldberg, K. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- AziendeEasy. Marinter Shipping Agency S.r.l.—Bilanci, Informazioni e Dati 2024. Available online: https://www.aziendeeasy.it/aziendaselezionata7169902-MARINTER%20SHIPPING%20AGENCY%20S.R.L (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Ufficio Camerale. Marinter Shipping Agency S.r.l.—Dati Camerali e Dipendenti. Available online: https://www.ufficiocamerale.it/9583/marinter-shipping-agency-srl (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Assoagenti Campania. Elenco Agenzie Marittime—Porto di Napoli. Available online: http://www.assoagenti-na.com/Assoagenti/?page_id=8 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- WRI; WBCSD. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard; World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ISPRA. Efficiency and Decarbonization Indicators in Italy and in the Biggest European Countries. Edition 2023; Rapporti 386/2023; Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale: Roma, Italy, 2023; ISBN 978-88-448-1161-7. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files2023/pubblicazioni/rapporti/r386-2023.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Czarniawska, B. Shadowing and Other Techniques for Doing Fieldwork in Modern Societies; Copenhagen Business School Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman, D.M. Ethnography: Step-by-Step, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Man, Y.; Sturm, T.; Lundh, M.; MacKinnon, S.N. From ethnographic research to big data analytics—A case of maritime energy-efficiency optimization. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannick, T.; Coghlan, D. In defense of being “native”: The case for insider academic research. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 10, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M. Beyond neopositivists, romantics, and localists: A reflexive approach to interviews in organizational research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv. Res. 1999, 34, 1189–1208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M.; Skaerbaek, P. Framing and overflowing of public sector accountability innovations. Account. Organ. Soc. 2007, 20, 101–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Larrinaga, C. Accounting and sustainable development: An exploration. Accounting Organ. Soc. 2014, 39, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, S.S.K. Accounting, female and male gendering and cultural imperialism. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Senkl, D. Gendering accountability: The discursive construction of authority in accounting and auditing. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2016, 35, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegmann, L.; Conrath-Hargreaves, A.; Guo, Z.; Hall, M.; Kober, R.; Pucci, R.; Thiagarajah, T. Methodological Insights: This is not an experiment: Using vignettes in qualitative accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2025, 38, 418–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repenning, N.; DeMott, K. Navigating the emotional challenges of ethnographic accounting research: Notes from first-time ethnographers. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2025, 22, 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.H.; Subramaniam, G.; Nasir, S. Women in Management at the Port Sector of Maritime Industry in Malaysia—Is There a Gender Imbalance? Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kitada, M.; Bhirugnath-Bhookhun, M. Beyond Business as Usual: The Role of Women Professionals in Maritime Clusters. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2019, 18, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, Z.; Woxenius, J.; Altuntas Vural, C.; Lind, M. Digital Transformation of Maritime Logistics: Exploring Trends in the Liner Shipping Segment. Comput. Ind. 2023, 145, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, A.A.; Ahsan, T.; Boubaker, S.; Roberto, F. Women on Board and Climate Change: An Illustration Through Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, M. The limits of accountability. Account. Organ. Soc. 2009, 34, 918–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Mastellone, L.; Lepore, L.; Varriale, L. Digitalization and performance management systems: A shipping agency case study. Manag. Control 2024, 2, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Appolloni, A.; Cavallaro, F.; D’Adamo, I.; Di Vaio, A.; Ferella, F.; Gastaldi, M.; Ikram, M.; Kumar, N.M.; Martin, M.A.; et al. Development goals towards sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, G.; D’Adamo, I.; Grosso, C.; Palmieri, R. Advancing Business Strategy in End-of-Life Management for the Fashion Industry. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2025, 34, 6814–6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, G.; Gasbarrone, R.; Palmieri, R.; Serranti, S. A Characterization Approach for End-of-Life Textile Recovery Based on Short-Wave Infrared Spectroscopy. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 1725–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviewee/Role | No. of Sessions | Total Duration (min) | Main Themes Covered | Dimensions (Economic, Social, Environmental) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managing Director (Board Member) | 2 | 120 (75; 45) | Organizational strategy; governance; accountability mechanisms; gender in decision-making; digitalization trajectory | ✔ Economic ✔ Social ✔ Environmental |

| Chief Financial Officer (CFO) | 2 | 110 (60; 50) | GHG accounting; ERP and e-invoicing; finance-driven sustainability; gender composition in accounting | ✔ Economic ✔ Social ✔ Environmental |

| Chief Operating Officer (COO) | 1 | 65 | Operational reporting; Afsys and Global OA; accountability towards principals; gendered allocation of tasks | ✔ Economic ✔ Social ✔ Environmental |

| HR/Compliance Officer | 1 | 45 | Recruitment, training, promotion policies; inclusive practices; gender and sustainability linkages | ✔ Social ✔ Environmental |

| Finance and Operations Staff (mixed group) | 5 | 200 (avg. 40) | Daily use of systems; data collection and reporting routines; perceptions of gender equality and accountability | ✔ Economic ✔ Social ✔ Environmental |

| Section | Example Items (Likert Scale) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Data quality and responsibility | “The data we provide for sustainability and carbon reporting are complete and accurate.” “Responsibilities for sustainability-related data are clear and well defined.” | Assess robustness of reporting processes |

| Training and digital systems | “I have received adequate training to use the digital systems that support reporting.” | Evaluate capacity-building and inclusivity in digitalization |

| Gender inclusivity | “Women and men in this organization have equal opportunities to access training and projects.” “Women have equal influence on decisions regarding reporting.” | Capture perceptions of gendered participation in accountability |

| Organizational climate | “I feel comfortable raising concerns about sustainability reporting without negative consequences.” “Carbon reporting is seen as a priority in my department.” | Assess accountability culture |

| Open-ended items | “What changes would improve the quality of sustainability and carbon data?” “What changes would improve gender inclusivity in accountability practices?” | Gather qualitative insights from staff |

| Routine Observed | Description | Analytical Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly Energy and Accounting Closure | Entry of utility bills, fuel logs, and reconciliations in TeamSystem Enterprise | Data quality, task allocation, gendered responsibility |

| Operational Reporting (Afsys, Global OA) | Export bookings, bills of landing, container loading/discharging lists transmitted to principals | Accountability to principals; digital traceability |

| Hyperion Uploads | Preparation and upload of monthly financial and operational reports to principal’s platform | Deadline pressures, stress, control over KPIs |

| Internal Meetings | Departmental discussions on sustainability and digital systems | Participation, voice, decision-making power |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Vaio, A.; Mastellone, L. GHG Accounting and Gendered Carbon Accountability in a Shipping Agency: A Single-Case Study with Ethnographic Elements. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310479

Di Vaio A, Mastellone L. GHG Accounting and Gendered Carbon Accountability in a Shipping Agency: A Single-Case Study with Ethnographic Elements. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310479

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Vaio, Assunta, and Luisa Mastellone. 2025. "GHG Accounting and Gendered Carbon Accountability in a Shipping Agency: A Single-Case Study with Ethnographic Elements" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310479

APA StyleDi Vaio, A., & Mastellone, L. (2025). GHG Accounting and Gendered Carbon Accountability in a Shipping Agency: A Single-Case Study with Ethnographic Elements. Sustainability, 17(23), 10479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310479