Food Waste and the Three Pillars of Sustainability: Economic, Environmental and Social Perspectives from Greece’s Food Service and Retail Sectors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Food Supply Chain, Food Waste Drivers, and Sectoral Impacts

2.2. The Economic, Social, and Environmental Impacts of Food Waste

2.2.1. Economic Impacts

2.2.2. Social Implications

2.2.3. Environmental Footprint

2.3. Practices and Technological Solutions for Reducing Food Waste

2.3.1. Prevention Strategies in Business and Households

2.3.2. Legislative Measures

2.3.3. The Role of Supply Chain Management

2.3.4. Digital Technologies and Applications

2.3.5. Economic Incentives and Policies

2.3.6. Global Best Practices

3. Case Study: Food Waste in Greece—A Comparative Analysis with the European Union and the United States

4. Analysis of Food Waste in the Food Service and Retail Sectors: An Empirical Study for Greece

4.1. Data and Methodology

Validity and Reliability of the Instrument

4.2. Results

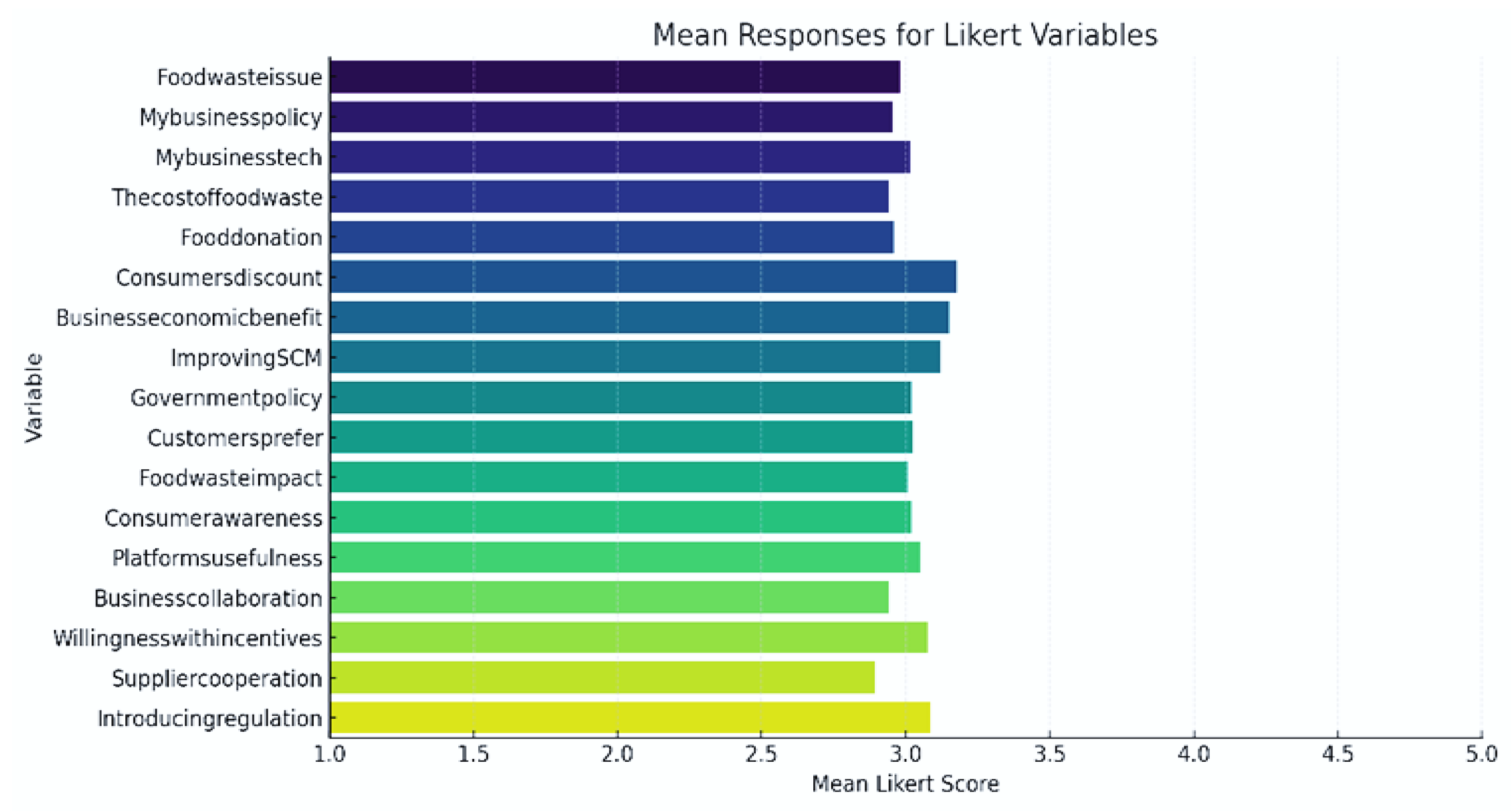

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

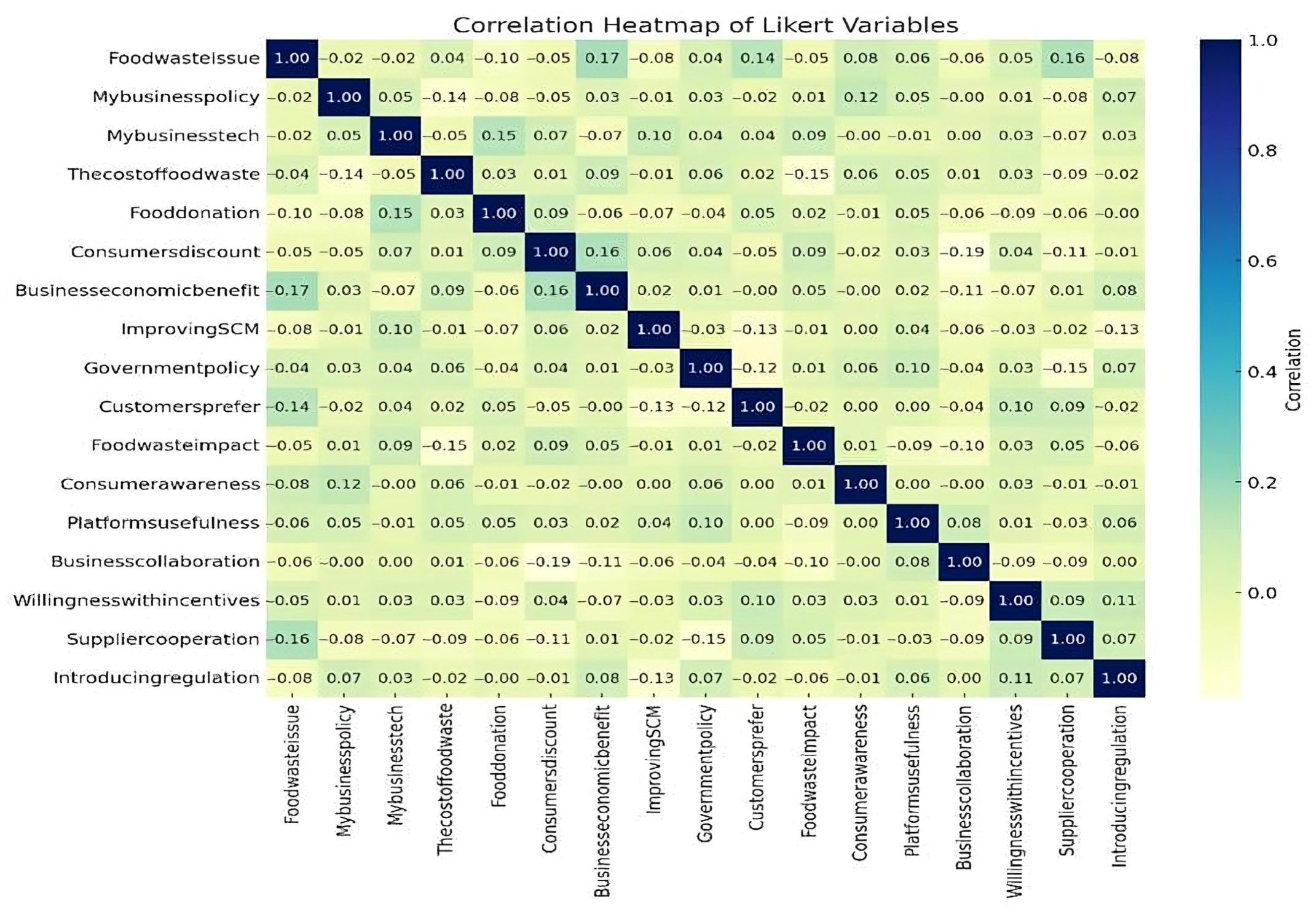

4.2.2. Correlation Analysis

4.2.3. Gender-Based Analysis on the Food Waste Problem

4.2.4. Regression Analysis and the Role of Demographics on the Food Waste Problem

- Gender: The coefficient for the female gender variable is 0.0727, with a p-value of 0.689. This means that, on average, women’s scores are only 0.07 points higher than men’s, a trivial and statistically insignificant difference.

- Age: Using the 18–24 age group as the baseline, all other age groups show no significant effect. The largest (though still insignificant) negative coefficient is for the 25–34 age group (−0.4659, p = 0.148), suggesting a slight tendency to perceive the problem as less important, but this is not a firm conclusion.

- Education: With a higher education level as the reference, both upper secondary and secondary education show insignificant negative coefficients (−0.23704, −0.06335). The perception of food waste’s importance is not meaningfully different across educational backgrounds.

- Professional Experience: With “1–3 years” of experience as the reference, there is no statistically significant effect from either more experience or a lack of it. This suggests that professional tenure in the sector does not significantly shape attitudes towards food waste.

4.3. Discussion

4.3.1. Interpretation and Comparison of Results

4.3.2. Theoretical Implications

4.3.3. Practical Implications

4.3.4. Limitations and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Variable Definitions (Selected)

- Foodwasteissue: Agreement that food waste is a significant problem (1–5).

- Mybusinesspolicy/Mybusinesshasapolicy: Agreement that the respondent’s firm has a policy to reduce food waste.

- Mybusinesstech: Agreement that the firm uses technological tools for inventory/stock management.

- Thecostoffoodwaste: Agreement that the cost of food waste is salient for the business.

- Consumersdiscount: Agreement that consumers are willing to purchase near expiry products at a discount.

- Businesseconomicbenefit: Agreement that reducing food waste yields economic benefits for the business.

- ImprovingSCM: Agreement that supply chain improvements can reduce food waste.

- Foodwasteimpact: Agreement that food waste imposes environmental burdens.

- Consumerawareness: Perception of consumer awareness regarding food waste.

- Platformsusefulness: Perceived usefulness of platforms for selling or allocating surplus/near expiry foods.

- Businesscollaboration/Suppliercooperation: Perceptions of collaboration with partners and suppliers to reduce waste.

- Introducingregulation/Governmentpolicy: Attitudes toward regulatory or policy interventions and government support.

Appendix A.2. Questionnaire

- Gender:

- 2.

- Age Group:

- 3.

- Education Level:

- 4.

- Professional Status:

- 5.

- Experience in the Food or Catering Industry:

- 6.

- Geographical Location of Business or Residence:

- 7.

- Food waste constitutes a significant problem in my business or daily life.

- 8.

- My business has a policy in place to limit food waste.

- 9.

- My business uses technological tools or digital applications to manage inventory and food waste.

- 10.

- The cost of food waste significantly affects my business’s finances.

- 11.

- Food discarded by my business or at home could be redistributed through social initiatives (e.g., food banks).

- 12.

- Consumers would purchase products at a discounted price if the expiration date was approaching.

- 13.

- Catering businesses can benefit economically from reducing food waste.

- 14.

- Improving supply chain management could significantly reduce food waste.

- 15.

- Government policies should support businesses investing in food waste reduction.

- 16.

- Customers prefer businesses that implement sustainability practices.

- 17.

- Food waste contributes significantly to environmental degradation.

- 18.

- Consumer awareness regarding food waste is insufficient.

- 19.

- Platforms for exchanging or selling surplus food products are useful in reducing food waste.

- 20.

- Businesses should collaborate with organizations to donate food that would otherwise be discarded.

- 21.

- I, or my business, would be willing to implement more food waste reduction practices if financial incentives or subsidies were available.

- 22.

- Collaboration with suppliers who adopt food waste reduction practices is important for my business.

- 23.

- The introduction of mandatory government regulations would be effective in reducing food waste.

References

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Food Waste Index Report 2021; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewska, M.; Kosicka-Gębska, M.; Gębski, J.; Żakowska-Biemans, S. Sustainable Food Waste Management in Food Service Establishments in Relation to Unserved Dishes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R.; Grebski, M.E. Analysis of Waste Trends in the European Union (2021–2023): Sectorial Contributions, Regional Differences, and Socio-Economic Factors. Foods 2025, 14, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, M.M.; Lago, A.; Pinto, N.G.M.; de Oliveira Araújo, C.; Velho, J.P. Systematic review of innovations in food packaging with a focus on circularity and the reduction of food loss and waste. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.; Schiefer, G. Sustainability in food networks. In Schriften der Gesellschaft für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften des Landbaues e.V.; Landwirtschaftsverlag: Münster, Germany, 2009; Volume 44, pp. 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regattieri, A.; Gamberi, M.; Manzini, R. Traceability of Food Products: General Framework and Experimental Evidence. J. Food Eng. 2007, 81, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Nuur, C.; Feldmann, A.; Birkie, S.E. Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kamilaris, A.; Kartakoullis, F.X.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. A Review on the Use of Blockchain for Food Supply Chains. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 22000:2018; Food Safety Management Systems. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65464.html (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- WRAP. Consumer Food Waste Survey; Waste and Resources Action Programme: Banbury, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ReFED. Insights from ReFED’s Food Waste Solutions; ReFED: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://refed.org/downloads/2021-mid-year-impact-report/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, S.; Macnaughtan, S. Food Waste in the Supply Chain. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Mirabella, N.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Current Options for Food Waste Treatment: A Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, T. Food Sustainability: The Role of Food Retail; The Food and Farming Futures Programme: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lebersorger, S.; Schneider, F. Discussion on the methodology for determining food waste in household waste composition studies. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1924–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; Bin, H. The Food Waste Hierarchy as a Framework for the Management of Food Waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 72, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1583933814386&uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Evans, D. Food Waste: Home Consumption, Material Culture and Everyday Life; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Court of Auditors. Tackling Food Waste: A European Issue; Special Report No 34/2016; Publications Office of the EU: Luxembourg, 2016; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/webpub/eca/special-reports/foodwaste-34-2016/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, K.A.L.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of Consumer Food Waste Behaviour: Two Routes to Food Waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Papamonioudis, K.; Zabaniotou, A. Exploring Greek Citizens’ Circular Thinking on Food Waste Recycling in a Circular Economy—A Survey-Based Investigation. Energies 2022, 15, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Waste Reduction Alliance. Best Practices and Emerging Solutions Toolkit; Food Waste Reduction Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). From Farm to Kitchen: The Environmental Impacts of U.S. Food Waste; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, P.; Brown, C.; Arneth, A.; Finnigan, J.; Rounsevell, M.D.A. Losses, Inefficiencies and Waste in the Global Food System. Agric. Syst. 2017, 153, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, C.; De Laurentiis, V.; Corrado, S.; Van Holsteijn, F.; Sala, S. Quantification of Food Waste per Product Group along the Food Supply Chain in the European Union. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrello, M.; Caracciolo, F.; Lombardi, A.; Pascucci, S.; Cembalo, L. Consumers’ Perspective on Circular-Economy Strategy for Reducing Food Waste. Sustainability 2017, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; De Coteau, D.A. Food waste management in hospitality operations: A critical review. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, K.M.; Reinhart, D.; Hawkins, C.; Motlagh, A.M.; Wright, J. Food Waste and the Food–Energy–Water Nexus: A Review of Food Waste Management Alternatives. Waste Manag. 2018, 74, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food Waste Matters—A Systematic Review of Household Food Waste Practices and Their Policy Implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Melacini, M.; Perego, A. Opening the Black Box of Food Waste Reduction. Food Policy 2014, 46, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Food Waste in the EU; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Food_waste_in_the_EU (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, A.; Browne, S. Food Waste and Nutrition Quality in the Context of Public Health: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, Z.; Blackstone, N.T. Identifying the links between consumer food waste, nutrition, and environmental sustainability: A narrative review. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza Orias, N.; Reynolds, C.J.; Ernstoff, A.S.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Cooper, K.; Aldaco, R. Editorial: Food Loss and Waste: Not All Food Waste Is Created Equal. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 615550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttlar, B.; Löwenstein, L.; Geske, M.-S.; Ahlmer, H.; Walther, E. Love Food, Hate Waste? Ambivalence towards Food Fosters People’s Willingness to Waste Food. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, H.; Williams, I.D.; Shaw, P.J.; Watanabe, K. Food waste prevention: Lessons from the Love Food, Hate Waste campaign in the UK. In Proceedings of the 16th International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium, S. Margherita di Pula, Cagliari, Italy, 2–6 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sgroi, F.; Totaro, T.; Modica, F.; Sciortino, C. A Digital Platform Strategy to Improve Food Waste Disposal Practices: Exploring the Case of “Too Good To Go”. Res. World Agric. Econ. 2024, 5, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Oroski, F.; Monteiro da Silva, J. Understanding food waste-reducing platforms: A mini-review. Waste Manag. Res. 2022, 41, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de l’Agriculture et de l’Alimentation. Gaspillage Alimentaire: Évaluation de l’Application des Dispositions Prévues par la loi Garot. 2020. Available online: https://agriculture.gouv.fr/gaspillage-alimentaire-evaluation-de-lapplication-des-dispositions-prevues-par-la-loi-garot (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Too Good to Go. Available online: https://www.toogoodtogo.com/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Van Boxstael, S.; Devlieghere, F.; Berkvens, D.; Vermeulen, A.; Uyttendaele, M. Understanding and attitude regarding the shelf life labels and dates on pre-packed food products by Belgian consumers. Food Control 2013, 37, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Food Waste. 2023. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/food-waste_en (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/851/oj/eng (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Aung, M.M.; Chang, Y.S. Traceability in a food supply chain: Safety and quality perspectives. Food Control 2014, 36, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.M.; Chiu, C.H.; Lee, H. Demand forecasting in the era of big data. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 221, 107474. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, F. A supply chain traceability system for food safety based on HACCP, Blockchain & Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management, Dalian, China, 16–18 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olio. Our Impact. Available online: https://olioapp.com/en/our-impact/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Karma. Connects Surplus Food with Consumers for a Lower Price. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/en/good-practices/karma-connects-surplus-food-consumers-lower-price (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- USDA. Good Samaritan Act Provides Liability Protection for Food Donations. United States Department of Agriculture. 2020. Available online: https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/blog/good-samaritan-act-provides-liability-protection-food-donations (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Zero Waste Europe. The Gadda Law: A New Step for Food Waste Prevention. 2021. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://zerowasteeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ZWE-Annual-Report-2021.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwji_ZjvwfyPAxVdcvEDHei7HVYQFnoECBgQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2AoCs2eHwBRd7dMN0lWshq (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Lee, E.; Shurson, G.; Oh, S.-H.; Jang, J.-C. The Management of Food Waste Recycling for a Sustainable Future: A Case Study on South Korea. Sustainability 2024, 16, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition Foundation and Economist Impact. Food Sustainability Index 2021: Fixing Food—An Opportunity for G20 Countries to Lead the Way. 2021. Available online: https://foodsustainability-cms.eiu.com/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/60857.html (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Juul, S. You have the power to stop wasting food. In Envisioning a Future Without Food Waste and Food Poverty; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Melacini, M.; Perego, A.; Sert, S. Reducing food waste in food manufacturing companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, V.; van Herpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Matyakubov, U.; Allonazarov, O.; Ermolaev, V.A. Food waste and its management in restaurants of a transition economy: An exploratory study of Uzbekistan. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. A technique for measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 5–55. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, H.N.; Boone, D.A. Analyzing Likert Data. J. Ext. 2012, 50, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 101, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Estimated Per Capita Food Waste (kg/Year) | Main Policy Framework/Legislation | Key Implementation Features | Challenges/Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | ~142 kg [26] | National Action Plan for Food Waste Reduction (2021) [21]; aligned with EU Directive 2018/851 [51] | Focus on awareness, prevention, redistribution, and monitoring; early-stage implementation; NGO engagement (e.g., platform “Boroume”) | Fragmented institutional coordination; lack of binding targets or economic incentives; limited technological adoption |

| Italy | ~146 kg [58] | Gadda Law (2016) [58]—National Food Waste and Donation Law | Tax incentives for donations; simplified bureaucracy; improved redistribution networks | Enforcement uneven across regions; limited data integration |

| France | ~134 kg [47] | Garot Law (2016) [47]—Anti-Food Waste Law | Legal obligation for supermarkets to donate unsold food; national awareness campaigns | Limited enforcement in small retailers; logistical challenges in redistribution |

| United States | ~200 kg [28] | Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act (1996) [57]; USDA/EPA Food Waste Challenge | Liability protection for donors; public–private partnerships (e.g., ReFED [14]); focus on technological innovation and data-driven monitoring | No federal mandate for waste reduction; heterogeneous state-level implementation |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foodwasteissue | 250 | 2.980 | 1.3897 |

| Mybusinesspolicy | 250 | 2.956 | 1.4347 |

| Mybusinesstech | 250 | 3.016 | 1.3941 |

| Thecostoffoodwaste | 250 | 2.944 | 1.4103 |

| Fooddonation | 250 | 2.960 | 1.3965 |

| Consumersdiscount | 250 | 3.176 | 1.4287 |

| Businesseconomicbenefit | 250 | 3.152 | 1.3858 |

| ImprovingSCM | 250 | 3.120 | 1.3976 |

| Governmentpolicy | 250 | 3.020 | 1.3693 |

| Customersprefer | 250 | 3.024 | 1.4055 |

| Foodwasteimpact | 250 | 3.008 | 1.3768 |

| Consumerawareness | 250 | 3.020 | 1.5195 |

| Platformsusefulness | 250 | 3.052 | 1.3626 |

| Businesscollaboration | 250 | 2.944 | 1.3639 |

| Willingnesswithincentives | 250 | 3.076 | 1.5044 |

| Suppliercooperation | 250 | 2.892 | 1.4256 |

| Introducingregulation | 250 | 3.088 | 1.3681 |

| Pair of Variables | r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Foodwasteissue—Foodwasteimpact | 0.0085 | 0.8939 |

| Mybusinesstech—Mybusinesspolicy | 0.0807 | 0.2037 |

| Consumerawareness—Platformsusefulness | 0.0189 | 0.7663 |

| Gender | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 2.95 | 1.46 | 118 |

| Women | 3.01 | 1.33 | 132 |

| Total | 2.98 | 1.39 | 250 |

| Group | N | Mean | SD | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 118 | 3.15 | 1.38 | [2.90, 3.40] |

| Women | 132 | 2.78 | 1.46 | [2.53, 3.03] |

| Difference | — | 0.37 * | 0.18 | [0.02, 0.73] |

| Variable | Coef. | SD | t | p-Value | [95% CI Lower] | [95% CI Upper] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender_f: Woman | 0.072736 | 0.181673 | 0.4 | 0.689 | −0.28516 | 0.430628 |

| AgeGroup_f: 25–34 | −0.46589 | 0.320651 | −1.45 | 0.148 | −1.09757 | 0.165784 |

| AgeGroup_f: 35–44 | −0.21325 | 0.333331 | −0.64 | 0.523 | −0.86991 | 0.443401 |

| AgeGroup_f: 45–54 | −0.33803 | 0.341418 | −0.99 | 0.323 | −1.01062 | 0.334561 |

| AgeGroup_f: 55–64 | −0.40484 | 0.314213 | −1.29 | 0.199 | −1.02384 | 0.214151 |

| AgeGroup_f: 65+ | 0.001995 | 0.334092 | 0.01 | 0.995 | −0.65616 | 0.660151 |

| Higher Education_f: | −0.06335 | 0.218774 | −0.29 | 0.772 | −0.49433 | 0.36763 |

| Secondary Education_f: | −0.23704 | 0.225933 | −1.05 | 0.295 | −0.68212 | 0.208046 |

| IndustryExp_f: 4–6 years | 0.004332 | 0.275566 | 0.02 | 0.987 | −0.53853 | 0.547192 |

| IndustryExp_f: 7+ years | 0.272837 | 0.254155 | 1.07 | 0.284 | −0.22784 | 0.773518 |

| IndustryExp_f: none | 0.220547 | 0.24999 | 0.88 | 0.379 | −0.27193 | 0.713022 |

| _cons | 3.159145 *** | 0.329481 | 9.59 | 0 | 2.510074 | 3.808217 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zervoudi, E.K.; Christopoulos, A.G.; Niotis, I. Food Waste and the Three Pillars of Sustainability: Economic, Environmental and Social Perspectives from Greece’s Food Service and Retail Sectors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229954

Zervoudi EK, Christopoulos AG, Niotis I. Food Waste and the Three Pillars of Sustainability: Economic, Environmental and Social Perspectives from Greece’s Food Service and Retail Sectors. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):9954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229954

Chicago/Turabian StyleZervoudi, Evanthia K., Apostolos G. Christopoulos, and Ioannis Niotis. 2025. "Food Waste and the Three Pillars of Sustainability: Economic, Environmental and Social Perspectives from Greece’s Food Service and Retail Sectors" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 9954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229954

APA StyleZervoudi, E. K., Christopoulos, A. G., & Niotis, I. (2025). Food Waste and the Three Pillars of Sustainability: Economic, Environmental and Social Perspectives from Greece’s Food Service and Retail Sectors. Sustainability, 17(22), 9954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229954