The Impact of Carbon Risk on Corporate Greenwashing Behavior: Inhibition or Promotion?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Hypothesis Development

3. Data and Empirical Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2. Measurement of Carbon Risk

3.3. Measurement of Greenwashing Behavior

3.4. Control Variables

3.5. Model Specification

4. Empirical Results and Discussions

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Pearson Correlation Analysis

4.3. Baseline Regression

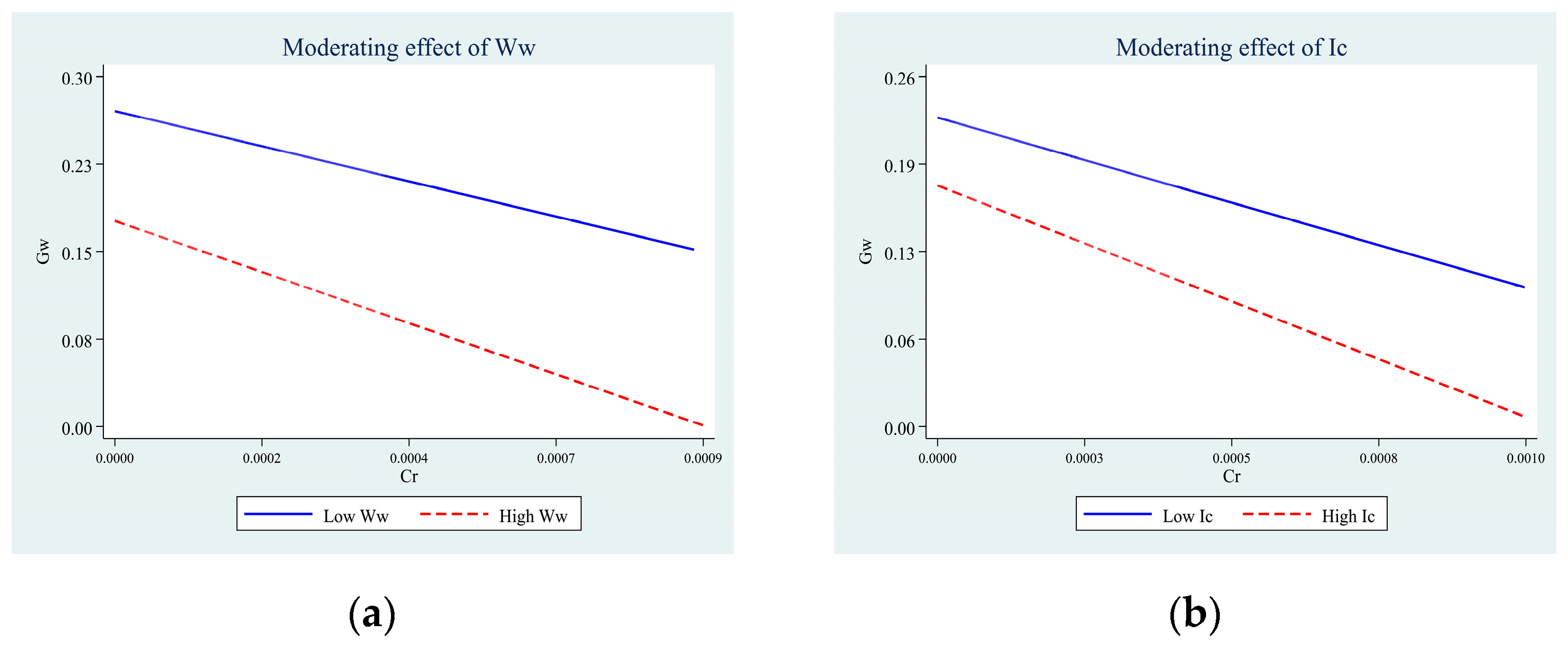

4.4. The Moderating Role of the Financial Constraints and Internal Controls

4.5. Robustness and Endogeneity Checks

4.5.1. Alternative Measure of Carbon Risks

4.5.2. Instrumental Variable (IV) Approach

4.5.3. Propensity Score Matching (PSM) Method

4.5.4. Replacement of the Regression Model

5. Further Investigations

6. Research Conclusions, Implications and Limitations

6.1. Research Conclusions

6.2. Managerial and Policy Implications

6.3. Potential Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tran, Q.H. The impact of green finance, economic growth and energy usage on CO2 emission in Vietnam–a multivariate time series analysis. China Financ. Rev. Int. 2022, 12, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Financial effects of carbon risk and carbon disclosure: A review. Account. Financ. 2023, 63, 4175–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Hou, R. Carbon risk and dividend policy: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 84, 102360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, P.; Kacperczyk, M. Do investors care about carbon risk? J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 517–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, D.H.B.; Tran, V.T.; Ming, T.C.; Le, A. Carbon risk and corporate investment: A cross-country evidence. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 46, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Minnick, K.; Shams, S. Does carbon risk matter for corporate acquisition decisions? J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 70, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Du, H.; Ren, M.; Zhen, W. Carbon information disclosure quality, greenwashing behavior, and enterprise value. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 892415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongbing, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, K. External financing demand, impression management and enterprise greenwashing. Comp. Econ. Soc. Syst. 2019, 3, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R. Does’ Enterprises’ Greenwashing affect Auditors’ decision making. Audit. Res 2020, 3, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, L.M. It’s not easy being green… or is it? A content analysis of environmental claims in magazine advertisements from the United States and United Kingdom. Environ. Commun. A J. Nat. Cult. 2012, 6, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lan, K. Does green finance policy contribute to esg disclosure of listed companies? a quasi-natural experiment from china. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241233376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders pressures encourage greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, D.; Espínola-Arredondo, A.; Munoz-Garcia, F. Can mandatory certification promote greenwashing? A signaling approach. J. Public Econ. Theory 2020, 22, 1801–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Li, Y. Media attention and corporate greenwashing behavior: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 55, 104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, C.; Foerstl, K.; Schleper, M.C. Antecedents of green supplier championing and greenwashing: An empirical study on leadership and ethical incentives. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 152, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, B. Study on the negative effect of internal-control willingness on enterprise risk-taking. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 894087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Are firms motivated to greenwash by financial constraints? Evidence from global firms’ data. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2022, 33, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Zhou, Y. Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, V.H.; Busch, T. Corporate carbon performance indicators: Carbon intensity, dependency, exposure, and risk. J. Ind. Ecol. 2008, 12, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labatt, S.; White, R.R. Carbon Finance: The Financial Implications of Climate Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, B. Firm-level carbon risk awareness and green transformation: A research on the motivation and consequences from government regulation and regional development perspective. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, E.; Sautner, Z.; Vilkov, G. Carbon tail risk. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2021, 34, 1540–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.H. Carbon risk and firm performance: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Aust. J. Manag. 2018, 43, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Álvarez, I.; Segura, L.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Carbon emission reduction: The impact on the financial and operational performance of international companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 103, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Eddie, I.; Liu, J. Carbon emissions and the cost of capital: Australian evidence. Rev. Account. Financ. 2014, 13, 400–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestreich, A.M.; Tsiakas, I. Carbon emissions and stock returns: Evidence from the EU Emissions Trading Scheme. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 58, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasterolo, I.; De Angelis, L. Blind to carbon risk? An analysis of stock market reaction to the Paris Agreement. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 170, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Zhang, J.; Xie, J.; Zhang, W. The impact of carbon risk on the pricing efficiency of the capital market: Evidence from a natural experiment in china. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Z. Experts on the board: How do IT-savvy directors promote corporate digital innovation? Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 791–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, B. Research on the Co-Evolution Mechanism of Electricity Market Entities Enabled by Shared Energy Storage: A Tripartite Game Perspective Incorporating Dynamic Incentives/Penalties and Stochastic Disturbances. Systems 2025, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Han, Z. How can carbon trading promote the green innovation efficiency of manufacturing enterprises? Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, L. Voluntary climate action and credible regulatory threat: Evidence from the carbon disclosure project. J. Regul. Econ. 2019, 56, 188–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauel, J.; Gotthardt, D. The relevance of national contexts for carbon disclosure decisions of stock-listed companies: A multilevel analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 1204–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-H.; Lyon, T.P. Strategic environmental disclosure: Evidence from the DOE’s voluntary greenhouse gas registry. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 61, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. The influence of institutional contexts on the relationship between voluntary carbon disclosure and carbon emission performance. Account. Financ. 2019, 59, 1235–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Luo, L. Corporate ecological transparency: Theories and empirical evidence. Asian Rev. Account. 2016, 24, 498–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Márquez, A.J.; González-González, J.M.; Zamora-Ramírez, C. An international empirical study of greenwashing and voluntary carbon disclosure. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Z.; He, B. Merging Economic Aspirations with Sustainability: ESG and the Evolution of the Corporate Development Paradigm in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Gatti, L. Greenwashing revisited: In search of a typology and accusation-based definition incorporating legitimacy strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Laine, M.; Roberts, R.W.; Rodrigue, M. Organized hypocrisy, organizational façades, and sustainability reporting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2015, 40, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.; Warren, D.E. The meaning and meaningfulness of corporate social initiatives. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2008, 113, 163–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.A.; Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Rashid, A.; Hammami, H. Carbon disclosure, carbon performance and financial performance: International evidence. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 75, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesso, G.; Kumar, K. Drivers of corporate voluntary disclosure: A framework and empirical evidence from Italy and the United States. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2007, 20, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma, T.T.; Feedman, M.; Mlilo, M.; Park, J.D. Corporate carbon risk, voluntary disclosure, and cost of capital: S outh A frican evidence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Reimsbach, D.; Schiemann, F. Organizations, climate change, and transparency: Reviewing the literature on carbon disclosure. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.W. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Account. Organ. Soc. 1992, 17, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.C.; Roberts, R.W. Toward a more coherent understanding of the organization–society relationship: A theoretical consideration for social and environmental accounting research. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, J.; Lokman, N.; Najah, M.M. Voluntary disclosure research: Which theory is relevant? J. Theor. Account. Res. 2011, 6, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Tan, R.; Zhang, B. The costs of “blue sky”: Environmental regulation, technology upgrading, and labor demand in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2021, 150, 102610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. The ethical, social and environmental reporting-performance portrayal gap. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2004, 17, 731–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.B.; Anderson, A.; Golden, S. Corporate environmental disclosures: Are they useful in determining environmental performance? J. Account. Public Policy 2001, 20, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.N.; Rahman, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Anwar, M. Carbon emissions and default risk: International evidence from firm-level data. Econ. Model. 2021, 103, 105617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, G.; He, Y.; Zhang, H. Greenwashing behaviors in construction projects: There is an elephant in the room! Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 64597–64621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, D.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhou, H. Internal controls, risk management, and cash holdings. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 64, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugh, M.; Ege, M.S.; Yust, C.G. Internal control quality and bank risk-taking and performance. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2021, 40, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulhaga, M.; Bouri, A.; Elamer, A.A.; Ibrahim, B.A. Environmental, social and governance ratings and firm performance: The moderating role of internal control quality. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, T.; Li, F.W.; Wen, Q. Is carbon risk priced in the cross section of corporate bond returns? J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2025, 60, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hua, R.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C. The green fog: Environmental rating disagreement and corporate greenwashing. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 78, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulet, T.J.; Touboul, S. The intentions with which the road is paved: Attitudes to liberalism as determinants of greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, M.K. Watchdog or lapdog? A behavioral view of the media as a corporate governance mechanism. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiambi, D.M.; Shafer, A. Corporate crisis communication: Examining the interplay of reputation and crisis response strategies. Mass Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkemeyer, R.; Faugère, C.; Gergaud, O.; Preuss, L. Media attention to large-scale corporate scandals: Hype and boredom in the age of social media. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Definitions | Symbols | Measurements |

|---|---|---|

| Greenwashing | Gw | Dummy variable indicating excessive green disclosure with poor environmental performance |

| Carbon Risk | Cr | Total carbon emissions divided by operating revenue (in millions). |

| Company Size | Size | Natural log of total assets. |

| Financial Leverage | Lev | Ratio of total liabilities to total assets |

| Return on Equity | Roe | Net operating income deflated by equity |

| Assets Turnover | Ato | Net sales deflated by total assets |

| Board Size | Board | Natural logarithm of the total number of directors on the board |

| The Proportion of Independent Directors | Indep | Natural logarithm of the total number of independent directors on the board |

| Variables | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gw | 33,458 | 0.1667 | 0.3727 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Cr | 33,458 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.0153 |

| Size | 33,458 | 22.2567 | 1.3237 | 19.3129 | 22.0351 | 26.4523 |

| Lev | 33,458 | 0.4187 | 0.2053 | 0.0278 | 0.4115 | 0.9343 |

| Roe | 33,458 | 0.0570 | 0.1459 | −2.1749 | 0.0699 | 0.4179 |

| Ato | 33,458 | 0.5921 | 0.3616 | 0.0475 | 0.5236 | 2.6445 |

| Board | 33,458 | 2.1228 | 0.1964 | 1.6094 | 2.1972 | 2.7081 |

| Indep | 33,458 | 0.3758 | 0.0537 | 0.2500 | 0.3636 | 0.6000 |

| Variables | Gw | Cr | Size | Lev | Roe | Ato | Board | Indep |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gw | 1.0000 | |||||||

| Cr | −0.0706 *** | 1.0000 | ||||||

| Size | 0.2979 *** | −0.0449 *** | 1.0000 | |||||

| Lev | 0.1568 *** | 0.0086 | 0.5197 *** | 1.0000 | ||||

| Roe | 0.0021 | −0.0385 *** | 0.0770 *** | −0.2137 *** | 1.0000 | |||

| Ato | 0.0370 *** | −0.0239 *** | 0.0066 | 0.0985 *** | 0.1379 *** | 1.0000 | ||

| Board | 0.0274 *** | 0.0224 *** | 0.2564 *** | 0.1591 *** | 0.0355 *** | 0.0254 *** | 1.0000 | |

| Indep | −0.0009 | −0.0065 | 0.0071 | −0.0065 | −0.0181 *** | −0.0364 *** | −0.5448 *** | 1.0000 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gw | Gw | Gw | |

| Cr | −87.8770 *** | −27.8666 *** | −25.0911 *** |

| (−5.6545) | (−5.2068) | (−4.4659) | |

| Size | 0.0906 *** | 0.0722 *** | 0.0776 *** |

| (24.8506) | (19.7215) | (10.5398) | |

| Lev | −0.0151 | 0.0587 *** | −0.0525 ** |

| (−0.7781) | (3.0961) | (−2.0194) | |

| Roe | −0.0765 *** | −0.0004 | 0.0203 |

| (−3.9640) | (−0.0190) | (1.1921) | |

| Ato | 0.0400 *** | 0.0458 *** | −0.0130 |

| (3.9792) | (4.7797) | (−0.8614) | |

| Board | −0.1457 *** | −0.0336 * | −0.0159 |

| (−7.4191) | (−1.7163) | (−0.5753) | |

| Indep | −0.3090 *** | −0.2020 *** | −0.0406 |

| (−4.4183) | (−2.9955) | (−0.4905) | |

| _cons | −1.4119 *** | −1.3356 *** | −1.4746 *** |

| (−16.0118) | (−15.6288) | (−8.2590) | |

| YearFE | No | Yes | Yes |

| FirmFE | No | No | Yes |

| F | 128.3776 | 108.0389 | 22.0612 |

| R2 | 0.0978 | 0.1493 | 0.4298 |

| N | 33458 | 33458 | 33458 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Gw | Gw | |

| Cr | −457.4147 ** | 83.0264 * |

| (−2.1803) | (1.8842) | |

| Ww | 0.2416 ** | |

| (2.4396) | ||

| Cr × Ww | −436.9225 ** | |

| (−1.9854) | ||

| Ic | 0.0088 | |

| (1.4897) | ||

| Cr × Ic | −40.5829 *** | |

| (−2.5974) | ||

| Size | 0.0664 *** | 0.0891 *** |

| (7.3963) | (9.9388) | |

| Lev | −0.0528 * | −0.0386 |

| (−1.9041) | (−1.2328) | |

| Roe | 0.0415 ** | 0.0289 |

| (2.3465) | (1.5789) | |

| Ato | −0.0214 | −0.0058 |

| (−1.3013) | (−0.3327) | |

| Board | −0.0146 | 0.0139 |

| (−0.4877) | (0.4293) | |

| Indep | −0.0572 | 0.0442 |

| (−0.6573) | (0.4635) | |

| _cons | −0.9801 *** | −1.8360 *** |

| (−4.9099) | (−8.4682) | |

| YearFE | Yes | Yes |

| FirmFE | Yes | Yes |

| F | 15.8712 | 15.7357 |

| R2 | 0.4331 | 0.4704 |

| N | 28,642 | 26,121 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gw | Cr | Gw | Gw | Gw | |

| Cr | −168.7523 ** | −32.2019 *** | −460.8562 ** | ||

| (−2.2658) | (−2.7287) | (−2.2844) | |||

| Cr2 | −0.0012 *** | ||||

| (−2.7104) | |||||

| Cr_Mean | 0.6850 *** | ||||

| (4.6978) | |||||

| Size | 0.0681 *** | −0.0001 *** | 0.0702 *** | 0.0862 *** | 0.6846 *** |

| (9.2434) | (−6.7392) | (8.4336) | (9.3320) | (8.6638) | |

| Lev | −0.0369 | 0.0000 * | −0.0489 * | −0.0584 * | 0.8042 *** |

| (−1.4575) | (1.7222) | (−1.8657) | (−1.6762) | (2.8619) | |

| Roe | 0.0221 | −0.0000 ** | 0.0163 | 0.0269 | 0.3327 * |

| (1.3004) | (−2.2121) | (0.9208) | (1.1830) | (1.9397) | |

| Ato | −0.0169 | −0.0001 *** | −0.0218 | −0.0220 | −0.0787 |

| (−1.1301) | (−6.2388) | (−1.3856) | (−1.1896) | (−0.5242) | |

| Board | −0.0224 | 0.0000 ** | −0.0099 | −0.0009 | 0.0163 |

| (−0.8232) | (2.4334) | (−0.3546) | (−0.0243) | (0.0570) | |

| Indep | −0.0841 | 0.0001 * | −0.0293 | 0.0176 | 0.2199 |

| (−1.0270) | (1.6934) | (−0.3513) | (0.1578) | (0.2625) | |

| _cons | −1.2520 *** | 0.0011 *** | N/A | −1.7031 *** | N/A |

| (−7.0524) | (7.4484) | N/A | (−7.5675) | N/A | |

| YearFE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FirmFE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F | 15.0589 | 9.7176 | 18.7245 | 16.0866 | N/A |

| R2/Pseudo R2 | 0.4078 | 0.2281 | 0.0007 | 0.4911 | 0.3418 |

| N | 32,333 | 33,370 | 33,370 | 16,474 | 18,564 |

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM | 21.336 *** | ||||

| Cragg–Donald Wald F | 680.648 [16.38] |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Less Negative News | More Negative News | |

| Gw | Gw | |

| Cr | −30.3949 *** | −19.2379 ** |

| (−3.0202) | (−2.5713) | |

| Size | 0.0885 *** | 0.0778 *** |

| (8.8179) | (8.0896) | |

| Lev | −0.0025 | −0.0839 ** |

| (−0.0674) | (−2.4557) | |

| Roe | 0.0372 | 0.0194 |

| (1.4220) | (0.8795) | |

| Ato | −0.0138 | −0.0061 |

| (−0.6619) | (−0.3127) | |

| Board | 0.0209 | −0.0391 |

| (0.5895) | (−1.0429) | |

| Indep | 0.1220 | −0.1613 |

| (1.1362) | (−1.4051) | |

| _cons | −1.8423 *** | −1.4181 *** |

| (−7.8269) | (−5.8056) | |

| YearFE | Yes | Yes |

| FirmFE | Yes | Yes |

| F | 15.6626 | 12.9777 |

| R2 | 0.4999 | 0.4844 |

| N | 16081 | 15922 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Z. The Impact of Carbon Risk on Corporate Greenwashing Behavior: Inhibition or Promotion? Sustainability 2025, 17, 10188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210188

Zhang C, Zhang S, Yang Y, Zhou Z. The Impact of Carbon Risk on Corporate Greenwashing Behavior: Inhibition or Promotion? Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210188

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Changjiang, Sihan Zhang, Ye Yang, and Zhepeng Zhou. 2025. "The Impact of Carbon Risk on Corporate Greenwashing Behavior: Inhibition or Promotion?" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210188

APA StyleZhang, C., Zhang, S., Yang, Y., & Zhou, Z. (2025). The Impact of Carbon Risk on Corporate Greenwashing Behavior: Inhibition or Promotion? Sustainability, 17(22), 10188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210188