Merging Economic Aspirations with Sustainability: ESG and the Evolution of the Corporate Development Paradigm in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

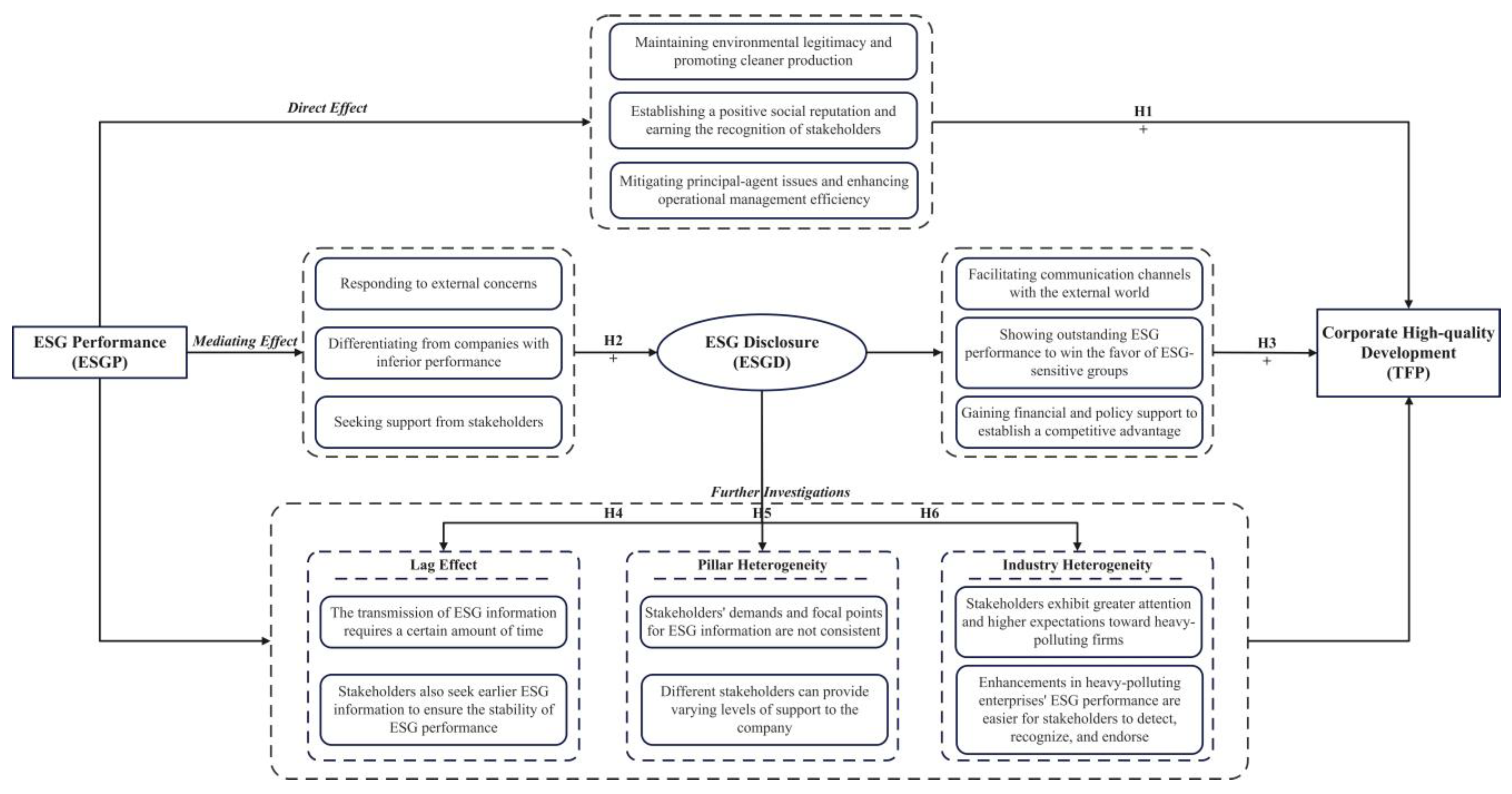

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Formulation

2.1. ESG Performance and Corporate High-Quality Development

2.2. ESG Performance and ESG Disclosure

2.3. The Mediating Role of ESG Disclosure

2.4. Industry Heterogeneity in the Promoting Effect of Corporate ESG Performance

3. Research Design and Model Construction

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Variable Definition and Measurement

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

3.3.2. Independent Variable

3.3.3. Mediating Variables

3.3.4. Control Variables

3.4. Model Specification

4. Empirical Analyses

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Pearson Correlation Analysis

4.3. Baseline Mediating Effect Test

5. Robustness Checks

5.1. Replacement of Mediating Role Test Methods

5.1.1. Sobel Test

5.1.2. Bootstrap Test

5.2. Replacement of TFP Measuring Methods

5.3. Instrumental Variable Strategy

6. Further Investigations

6.1. The Lag Effect Test

6.2. The Pillar Heterogeneity Test

6.3. The Industry Heterogeneity Test

7. Research Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

7.1. Research Conclusions

7.2. Managerial and Policy Implications

7.3. Possible Limitations and Research Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, P.D.; Zhu, B.Y.; Yang, M.Y. Has marine technology innovation promoted the high-quality development of the marine economy?—Evidence from coastal regions in China. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 209, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Instrumental stakeholder theory—A synthesis of ethics and economics. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1995, 20, 404–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.; Anderson, K.; Toms, S. Does Community and Environmental Responsibility Affect Firm Risk? Evidence from UK Panel Data 1994–2006. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2011, 20, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabati, A.A.A. Effect of corporate social responsibility on Jordan pharmaceutical industry’s business performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliwa, Y.; Aboud, A.; Saleh, A. ESG practices and the cost of debt: Evidence from EU countries. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2021, 79, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogi, M.; Lagasio, V. Environmental, social, and governance and company profitability: Are financial intermediaries different? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.D.; McLaughlin, C.P. The impact of environmental management on firm performance. Manage. Sci. 1996, 42, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.; Lu, Y.; Shi, X.Z.; Yin, Q. How do investors respond to Green Company Awards in China? Ecol. Econ. 2013, 94, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, A.; Liang, H.; Renneboog, L. Socially responsible firms. J. Financ. Econ. 2016, 122, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J.P. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.P.; Covin, J.G. Environmental marketing: A source of reputational, competitive, and financial advantage. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.M.; Fooladi, I.J. Sustainable finance: A new paradigm. Glob. Financ. J. 2013, 24, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katircioglu, S.; Katircioglu, S. The effects of environmental taxation on stock returns of renewable energy producers: Evidence from Turkey. Renew. Energy 2023, 208, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Xiao, X.; Li, Z.; Dai, Q. Does ESG Performance Promote High-Quality Development of Enterprises in China? The Mediating Role of Innovation Input. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting in China. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2014, 23, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hąbek, P. Trends in Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. The Case of Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.X.; Wang, H. Comprehensive evaluation of urban high-quality development: A case study of Liaoning Province. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.C.; Wang, X.H.; Hu, S.L. Accountability audit of natural resource, air pollution reduction and political promotion in China: Empirical evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 287, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Lou, J.; He, B. Greening Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: The Impact of China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Pilot Policy on Listed Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, N.; Adamson, R. Managing the “S” in ESG: The Case of Indigenous Peoples and Extractive Industries. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2016, 28, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, R.; Xu, L.C.; Yang, X.; Zhou, L.A.; Zhu, T. Market facilitation by local government and firm efficiency: Evidence from China. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 42, 460–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Z.X. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) activity and firm performance: A review and consolidation. Account. Financ. 2021, 61, 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, T.; Vaccaro, A. Stakeholders Matter: How Social Enterprises Address Mission Drift. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Ma, C. Can the Inclusiveness of Foreign Capital Improve Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, D.; Rasche, A.; Etzion, D.; Newton, L. Corporate Sustainability Management and Environmental Ethics Introduction. Bus. Ethics Q. 2017, 27, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.R. Cleantech clusters: Transformational assemblages for a just, green economy or just business as usual? Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2013, 23, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability—An investigation into the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.L.; Fisher, R.; Kwoh, Y. Technological challenges of green innovation and sustainable resource management with large scale data. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Walker, M.; Zeng, C. Do Chinese state subsidies affect voluntary corporate social responsibility disclosure? J. Account. Public Policy 2017, 36, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Clelland, I. Talking trash: Legitimacy, impression management, and unsystematic risk in the context of the natural environment. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, S.; Cellier, A.; Manita, R.; Saeed, A. Does corporate social responsibility reduce financial distress risk? Econ. Model. 2020, 91, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvathova, E. Does environmental performance affect financial performance? A meta-analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 70, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Burgos-Jimenez, J.; Vazquez-Brust, D.; Plaza-Ubeda, J.A.; Dijkshoorn, J. Environmental protection and financial performance: An empirical analysis in Wales. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 981–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Olanipekun, A.; Chen, Q.; Xie, L.L.; Liu, Y. Conceptualising the state of the art of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the construction industry and its nexus to sustainable development. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 195, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grip, A.; Sauermann, J. The Effects of Training on Own and Co-worker Productivity: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Econ. J. 2012, 122, 376–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Zhang, C.D. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Risk: Theory and Empirical Evidence. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 4451–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Why resource-based theory’s model of profit appropriation must incorporate a stakeholder perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 3305–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. The resource-based view of the firm—10 years after. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Lead to Superior Financial Performance? A Regression Discontinuity Approach. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 2549–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S. Corporate governance and development. World Bank Res. Observ. 2006, 21, 91–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, A. Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 101, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Value: The Role of Customer Awareness. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktan, M.S.; Kieschnick, R.; Moussawi, R. Corporate Governance and Firm Survival. Financ. Rev. 2018, 53, 209–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of firm—Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Choi, C.; Kim, J.M. Outside directors’ social capital and firm performance: A complex network approach. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2012, 40, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, B.S.; Kim, W.; Jang, H.; Park, K.S. How corporate governance affect firm value? Evidence on a self-dealing channel from a natural experiment in Korea. J. Bank Financ. 2015, 51, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.E.; Liu, Q.; Lu, J.; Song, F.M.; Zhang, J.X. Corporate governance and market valuation in China. J. Comp. Econ. 2004, 32, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulz, R.M. Managerial discretion and optimal financing policies. J. Financ. Econ. 1990, 26, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Safieddine, A.M.; Rabbath, M. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Synergies and Interrelationships. Corp. Gov. 2008, 16, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Sanchez, P.; de la Cuesta-Gonzalez, M.; Paredes-Gazquez, J.D. Corporate social performance and its relation with corporate financial performance: International evidence in the banking industry. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 162, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badía, G.; Gómez-Bezares, F.; Ferruz, L. Are investments in material corporate social responsibility issues a key driver of financial performance? Account. Financ. 2022, 62, 3987–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, A.; Roberts, G.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. J. Bank Financ. 2011, 35, 1794–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.B.; Anbumozhi, V. Determinant factors of corporate environmental information disclosure: An empirical study of Chinese listed companies. J. Clean Prod. 2009, 17, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, R.A. Disclosure of nonproprietary information. J. Account. Res. 1985, 23, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Guo, X. The relationships between reporting format, environmental disclosure and environmental performance An empirical study. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2017, 18, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy—Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockness, J.W. An assessment of the relationship between US corporate environmental performance and disclosure. J. Bus. Finan. Account. 1985, 12, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archel, P.; Husillos, J.; Larrinaga, C.; Spence, C. Social disclosure, legitimacy theory and the role of the state. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2009, 22, 1284–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, C.; Fraas, J.W. Coming Clean: The Impact of Environmental Performance and Visibility on Corporate Climate Change Disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Yu, L.H. How does state-owned shares affect double externalities and industrial performance: Evidence from China’s exhaustible resources industry. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 176, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Zhang, J.; Delaurentis, T. Quality control in food supply chain management: An analytical model and case study of the adulterated milk incident in China. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 152, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Lei, Z. Does the expansion of Chinese state-owned enterprises affect the innovative behavior of private enterprises? Asia-Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2015, 22, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Shang, L. ESG disclosure and corporate financial irregularities—Evidence from Chinese listed firms. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 332, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhong, C. Does Environmental Information Disclosure Affect the Sustainable Development of Enterprises: The Role of Green Innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizoumi, T.; Lazaridis, S.; Stamou, N. Innovation in Stock Exchanges: Driving ESG Disclosure and Performance. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2019, 31, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.; Javakhadze, D. Corporate social responsibility and capital allocation efficiency. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 43, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Q.; Li, X.M.; Tian, S.H.; He, L.Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X. Quantifying the dynamics between environmental information disclosure and firms’ financial performance using functional data analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2021, 28, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.L.; Wang, Y.; Zuo, J.; Jiang, H.Q.; Huang, D.C.; Rameezdeen, R. Characteristics of public concern on haze in China and its relationship with air quality in urban areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 637, 1597–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C. Value Maximization, Stakeholder Theory, and the Corporate Objective Function. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2010, 22, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zeng, M.; Jin, Y.L.; Zeng, H.X. Does China’s river chief policy improve corporate water disclosure? A quasi-natural experimental. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 311, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Y.; Bansal, P. Social responsibility in new ventures: Profiting from a long-term orientation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Salomon, R.M. Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluchna, M.; Roszkowska-Menkes, M.; Kamiński, B.; Bosek-Rak, D. Do institutional investors encourage firm to social disclosure? The stakeholder salience perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B. Stakeholder theory and “the corporate objective revisited”. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Measuring corporate performance by building on the stakeholders model of business ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 35, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Wood, D.J.; Agle, B. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; López-Gutiérrez, C. An empirical analysis of the relationship between the information quality of CSR reporting and reputation among publicly traded companies in Spain. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2017, 30, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Burritt, R.; Qian, W. Salient stakeholders in corporate social responsibility reporting by Chinese mining and minerals companies. J. Clean Prod. 2014, 84, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Hung, M.Y.; Wang, Y.X. The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firm profitability and social externalities: Evidence from China. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lee, J.; Moon, S. Employee response to CSR in China: The moderating effect of collectivism. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 839–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. The core of China’s rural revitalization: Exerting the functions of rural area. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2019, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, T.; Han, L.; Liu, Y. Does targeted poverty alleviation disclosure improve stock performance? Econ. Lett. 2021, 201, 109805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shao, S. The economic consequences of environmental regulation in China: From a perspective of the environmental protection admonishing talk policy. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 1723–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Strezov, V. Empirical study of the Environmental Kuznets curve and Environmental Sustainability curve hypothesis for Australia, China, Ghana and USA. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 201, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, P. Does policy uncertainty affect corporate environmental information disclosure: Evidence from China. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 903–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugui, L.; Bing, X.; Bing, X. Improving public access to environmental information in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 88, 1649–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chan, K.; Cheng, L.T.W.; Wang, X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbebi, A.; Lassoued, N.; Khanchel, I. Peering through the smokescreen: ESG disclosure and CEO personality. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 43, 3147–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M.A.; Hoepner, A.G.F.; Li, Q. A stakeholder resource-based view of corporate social irresponsibility: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 830–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Li, Y.; Tan, L. Can environmental regulation break the political resource curse: Evidence from heavy polluting private listed companies in China. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 67, 3190–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Lee, J.H.; Byun, R. Does ESG Performance Enhance Firm Value? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Guo, X.; Zhong, S.; Wang, J. Environmental information disclosure quality, media attention and debt financing costs: Evidence from Chinese heavy polluting listed companies. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 231, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Bai, E.; Zhu, H.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, H. Can Green Credit Policy Promote the High-Quality Development of China’s Heavily-Polluting Enterprises? Sustainability 2023, 15, 8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.-J.; Zhou, L.-J.; Zhou, M.; Pei, F. Financial Distress Prediction: A Novel Data Segmentation Research on Chinese Listed Companies. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2021, 27, 1413–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sanchez, I.M.; Gomez-Miranda, M.E.; David, F.; Rodriguez-Ariza, L. Analyst coverage and forecast accuracy when CSR reports improve stakeholder engagement: The Global Reporting Initiative-International Finance Corporation disclosure strategy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1392–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Lim, E.K.; Qu, W.; Zhang, X. Board cultural diversity, government intervention and corporate innovation effectiveness: Evidence from China. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2021, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Q. Comparative analysis of total factor productivity in China’s high-tech industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Ju, Y.; Dong, P.; Giannakis, M.; Wang, A.; Liang, Y.; Wang, H. Evaluate and select state-owned enterprises with sustainable high-quality development capacity by integrating FAHP-LDA and bidirectional projection methods. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 329, 129771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Jiang, C.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Hao, Y. Corporate Social Responsibility and High-quality Development: Do Green Innovation, Environmental Investment and Corporate Governance Matter? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 3191–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Trainor, M. Capital subsidies and their impact on total factor productivity: Firm-level evidence from Northern Ireland. J. Reg. Sci. 2005, 45, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Huang, D.-H. Contribution of factor structure change to China’s economic growth: Evidence from the time-varying elastic production function model. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2019, 33, 2919–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, D. Market imperfections, trade reform and total factor productivity growth: Theory and practices from India. J. Product. Anal. 2012, 40, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinsohn, J.; Petrin, A. Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2003, 70, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Goodell, J.W.; Shen, D. ESG rating and stock price crash risk: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 46, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. ESG and Firm’s Default Risk. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolandi, C.; Eccles, R.G.; Gabbi, G. How material is a material issue? Stock returns and the financial relevance and financial intensity of ESG materiality. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2020, 12, 1045–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, R.Y.J. A review of corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 164, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankova, P.; Valeva, M.; Štrukelj, T. A Comparative Analysis of International Corporate Social Responsibility Standards as Enterprise Policy/Governance Innovation Guidelines. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2015, 32, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Wu, S. Corporate sustainability and analysts’ earnings forecast accuracy: Evidence from environmental, social and governance ratings. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, C. Resiliency of Environmental and Social Stocks: An Analysis of the Exogenous COVID-19 Market Crash. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2020, 9, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzani, A.; Wan-Hussin, W.N.; Jones, M.; Al-hadi, A. ESG Reporting and Analysts’ Recommendations in GCC: The Moderation Role of Royal Family Directors. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.X.; Xu, X.D.; Dong, Z.Y.; Tam, V.W.Y. Towards corporate environmental information disclosure: An empirical study in China. J. Clean Prod. 2010, 18, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, B.; Stulz, R.; Wang, Z.X. Does the stock market make firms more productive? J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 136, 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi, A.; Glaum, M.; Kaiser, S. ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 38, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Xu, Y.; Hao, Y.; Wu, H.; Xue, Y. What is the role of telecommunications infrastructure construction in green technology innovation? A firm-level analysis for China. Energy Econ. 2021, 103, 105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q. R&D Investment and Total Factor Productivity: An Empirical Study of the Listed Companies in the Coastal Regions of China. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 106, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research—Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Chang, L.; Hau, K.-T.; Liu, H.Y. Testing and application of the mediating effects. Acta. Psychol. Sin. 2004, 36, 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, M.D.; Fang, Z.W.; Li, Z.H. Does Business Group’s Conscious of Social Responsibility Enhance its Investment Efficiency? Evidence from ESG Disclosure of China’s Listed Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Li, T.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, M. Do political connections facilitate or inhibit firms’ digital transformation? Evidence from Chi-na’s A-share private listed companies. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0302586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhi, Y.P.; Deng, Z.W.; Gao, Q.; Jiang, R. Crowding-Out or Crowding-In: Government Health Investment and Household Consumption. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, V.; Monteiro, S. Knowledge Processes, Absorptive Capacity and Innovation: A Mediation Analysis. Knowl. Process Manag. 2016, 23, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Jiang, P. Can digital finance improve enterprise total factor productivity? Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2021, 23, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J. Corporate ESG Performance and Corporate Short-Term Debt for Long-Term Use. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2023, 40, 152–172. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Huang, J.; Zhao, S. Internalizing governance externalities: The role of institutional cross-ownership. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 134, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glen, J.; Lee, K.; Singh, A. Persistence of profitability and competition in emerging markets. Econ. Lett. 2001, 72, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwandtner, A. Profile persistence in the ‘very’ long run: Evidence from survivors and exiters. Appl. Econ. 2005, 37, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.H.; Jeong, S.W.; Lee, W.J.; Bae, S.H. Permanency of CSR Activities and Firm Value. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 152, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Luo, W.; Wang, Y.P.; Wu, L.S. Firm performance, corporate ownership, and corporate social responsibility disclosure in China. Bus. Ethics 2013, 22, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zheng, Y. Does CSR reporting matter to foreign institutional investors in China? J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2020, 40, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Zhang, D.Y.; Zhang, T.; Ji, Q.; Lucey, B. Awareness, energy consumption and pro-environmental choices of Chinese households. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 279, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Cui, W. Study on the mechanism of ESG promoting corporate performance: Based on the perspective of corporate innovation. Sci. Sci. Manag. S.&.T 2021, 42, 71–89. [Google Scholar]

| Rating | AAA | AA | A | BBB | BB | B | CCC | CC | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Type | Variable | Variable Definition | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | TFP | Total factor productivity estimated using the LP method; natural logarithm taken. | CSMAR |

| Independent variable | ESGP | ESG performance rating from the Sino-Securities Index, scaled from 1 to 9. | Sino-Securities Index |

| Mediating variables | ESGD | Composite ESG disclosure score from Bloomberg. | Bloomberg |

| ED | Environmental disclosure score. | Bloomberg | |

| SD | Social disclosure score. | Bloomberg | |

| GD | Governance disclosure score. | Bloomberg | |

| Control variables | Size | Natural logarithm of total assets. | CSMAR |

| Own | Ownership type indicator: 1 = state-owned enterprise; 0 = non-state-owned enterprise. | ||

| ListAge | Natural logarithm of years since listing. | ||

| Lev | Total liabilities/total assets. | ||

| ROA | Net income/total assets. | ||

| Cashflow | Operating cash flow/total assets. | ||

| Indep | Number of independent directors/total number of directors. | ||

| ATO | Operating income/total assets. |

| Variables | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | 11,841 | 9.000 | 1.039 | 5.476 | 8.955 | 11.127 |

| ESGP | 11,841 | 4.430 | 1.082 | 1.000 | 4.000 | 8.000 |

| ESGD | 11,841 | 28.857 | 9.525 | 9.909 | 28.005 | 57.439 |

| ED | 11,841 | 9.296 | 12.786 | 0.000 | 1.933 | 54.153 |

| SD | 11,841 | 13.587 | 7.785 | 0.000 | 12.001 | 38.876 |

| GD | 11,841 | 63.923 | 14.087 | 29.651 | 69.296 | 89.856 |

| Size | 11,841 | 23.156 | 1.287 | 19.665 | 23.065 | 26.062 |

| Own | 11,841 | 0.545 | 0.498 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| ListAge | 11,841 | 2.487 | 0.638 | 0.693 | 2.639 | 3.332 |

| Lev | 11,841 | 0.479 | 0.196 | 0.053 | 0.491 | 0.882 |

| ROA | 11,841 | 0.052 | 0.061 | −0.219 | 0.043 | 0.219 |

| Cashflow | 11,841 | 0.061 | 0.070 | −0.171 | 0.057 | 0.249 |

| Indep | 11,841 | 37.523 | 5.594 | 14.290 | 36.360 | 57.140 |

| ATO | 11,841 | 0.701 | 0.483 | 0.072 | 0.591 | 2.723 |

| Variables | TFP | ESGP | ESGD | ED | SD | GD | Size | Own | ListAge | Lev | ROA | Cashflow | Indep | ATO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ESGP | 0.180 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| ESGD | 0.386 *** | 0.190 *** | 1 | |||||||||||

| ED | 0.333 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.843 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| SD | 0.303 *** | 0.268 *** | 0.758 *** | 0.677 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| GD | 0.285 *** | 0.070 *** | 0.815 *** | 0.426 *** | 0.404 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Size | 0.777 *** | 0.183 *** | 0.461 *** | 0.385 *** | 0.346 *** | 0.361 *** | 1 | |||||||

| Own | 0.182 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.007 | 0.018 * | 0.022 ** | −0.034 *** | 0.266 *** | 1 | ||||||

| ListAge | 0.175 *** | −0.021 ** | 0.188 *** | 0.105 *** | 0.065 *** | 0.205 *** | 0.245 *** | 0.320 *** | 1 | |||||

| Lev | 0.452 *** | −0.014 | 0.043 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.490 *** | 0.238 *** | 0.224 *** | 1 | ||||

| ROA | 0.047 *** | 0.112 *** | 0.006 | 0.036 *** | 0.035 *** | −0.036 *** | −0.111 *** | −0.195 *** | −0.236 *** | −0.448 *** | 1 | |||

| Cashflow | 0.034 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.097 *** | 0.099 *** | 0.077 *** | 0.058 *** | −0.027 *** | −0.085 *** | −0.082 *** | −0.251 *** | 0.492 *** | 1 | ||

| Indep | 0.073 *** | 0.107 *** | 0.089 *** | 0.055 *** | 0.067 *** | 0.092 *** | 0.085 *** | 0 | −0.008 | 0.024 *** | −0.003 | 0.001 | 1 | |

| ATO | 0.500 *** | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.050 *** | 0.037 *** | −0.053 *** | 0.003 | 0.013 | −0.037 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.186 *** | 0.146 *** | −0.006 | 1 |

| Variables | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| ESGP | 1.10 | 0.91 |

| ESGD | 1.44 | 0.69 |

| Size | 1.95 | 0.51 |

| Own | 1.23 | 0.81 |

| ListAge | 1.22 | 0.82 |

| Lev | 1.87 | 0.54 |

| ROA | 1.74 | 0.58 |

| Cashflow | 1.35 | 0.74 |

| Indep | 1.02 | 0.98 |

| ATO | 1.10 | 0.91 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | ESGD | TFP | |

| ESGP | 0.009 *** | 0.605 *** | 0.008 *** |

| (3.251) | (11.122) | (2.941) | |

| ESGD | 0.001 *** | ||

| (2.658) | |||

| Size | 0.577 *** | 1.284 *** | 0.575 *** |

| (63.686) | (10.873) | (63.058) | |

| Own | −0.048 ** | −0.083 | −0.047 ** |

| (−2.324) | (−0.317) | (−2.321) | |

| ListAge | 0.048 *** | −0.349 | 0.048 *** |

| (3.491) | (−1.266) | (3.522) | |

| Lev | 0.122 *** | −2.490 *** | 0.125 *** |

| (3.309) | (−5.092) | (3.399) | |

| ROA | 0.693 *** | 3.637 *** | 0.688 *** |

| (9.135) | (3.544) | (9.069) | |

| Cashflow | 0.302 *** | 1.658 ** | 0.299 *** |

| (5.896) | (2.248) | (5.850) | |

| Indep | 0.000 | 0.031 *** | 0.000 |

| (0.661) | (2.697) | (0.590) | |

| ATO | 0.973 *** | 0.355 | 0.972 *** |

| (52.424) | (1.636) | (52.416) | |

| YearFE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FirmFE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −5.306 *** | −3.162 | −5.301 *** |

| (−26.252) | (−1.174) | (−26.209) | |

| F-values | 947.181 | 38.442 | 858.935 |

| Observations | 11,841 | 11,841 | 11,841 |

| R-squared | 0.963 | 0.844 | 0.963 |

| Type of Test | Sobel–Goodman Test |

|---|---|

| Coefficient of Test | 0.004 *** |

| Z | 8.079 |

| Proportion of Mediating Role | 11.1% |

| Type of Test | Bootstrap Test |

|---|---|

| Coefficient of Test | 0.004 *** |

| Lower Limit of the 95% Confidence Interval | 0.003 |

| Upper Limit of the 95% Confidence Interval | 0.005 |

| Z | 7.87 |

| Times of Repetition | 1000 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP_OLS | TFP_OLS | TFP_FE | TFP_FE | ESGP | TFP | |

| ESGP | 0.006 ** | 0.005 ** | 0.006 ** | 0.006 ** | 0.167 ** | |

| (2.333) | (1.992) | (2.552) | (2.194) | (2.245) | ||

| ESGD | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | ||||

| (3.010) | (3.175) | |||||

| Value | 0.000 *** | |||||

| (3.104) | ||||||

| Size | 0.781 *** | 0.779 *** | 0.833 *** | 0.831 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.534 *** |

| (105.595) | (104.589) | (113.253) | (112.168) | (10.015) | (23.910) | |

| Own | −0.048 *** | −0.048 *** | −0.045 *** | −0.045 *** | 0.182 *** | −0.068 ** |

| (−2.987) | (−2.982) | (−2.903) | (−2.897) | (2.902) | (−2.535) | |

| ListAge | 0.069 *** | 0.070 *** | 0.071 *** | 0.071 *** | 0.165 *** | 0.019 |

| (5.963) | (5.997) | (6.139) | (6.175) | (3.302) | (0.951) | |

| Lev | 0.127 *** | 0.130 *** | 0.131 *** | 0.135 *** | −0.960 *** | 0.269 *** |

| (3.638) | (3.731) | (3.709) | (3.805) | (−9.615) | (3.231) | |

| ROA | 0.383 *** | 0.378 *** | 0.327 *** | 0.321 *** | 0.806 *** | 0.535 *** |

| (5.544) | (5.470) | (4.716) | (4.639) | (3.411) | (4.969) | |

| Cashflow | 0.446 *** | 0.443 *** | 0.461 *** | 0.459 *** | −0.543 *** | 0.372 *** |

| (10.043) | (9.989) | (10.448) | (10.391) | (−3.677) | (5.369) | |

| Indep | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | 0.020 *** | −0.003 * |

| (0.026) | (−0.059) | (−0.206) | (−0.296) | (8.969) | (−1.686) | |

| ATO | 0.972 *** | 0.971 *** | 0.981 *** | 0.980 *** | −0.086 * | 0.983 *** |

| (55.018) | (55.030) | (55.222) | (55.239) | (−1.959) | (48.540) | |

| YearFE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FirmFE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −7.403 *** | −7.399 *** | −7.969 *** | −7.964 *** | −1.787 *** | N/A |

| (−45.10) | (−45.07) | (−48.85) | (−48.82) | (−3.324) | N/A | |

| F-values | 1913.092 | 1728.897 | 2145.441 | 1939.473 | 36.634 | 782.648 |

| Observations | 11,841 | 11,841 | 11,841 | 11,841 | 11,658 | 11,658 |

| R-squared | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.981 | 0.981 | 0.544 | 0.579 |

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM | 16.440 *** | |||||

| Cragg–Donald Wald F | 17.877 [16.38] |

| Periods Lagged | No Period Lagged | One Period Lagged | Two Periods Lagged |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sobel–Goodman Test | 0.004 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.005 *** |

| Z | 8.079 | 7.713 | 7.433 |

| Proportion of Mediating Role | 11.1% | 12.5% | 13.9% |

| ESG Disclosure Pillar | ED | SD | GD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sobel–Goodman Test | 0.001 ** | 0.004 *** | 0.000 |

| Z | 3.120 | 4.864 | 1.225 |

| Proportion of Mediating Role | 3.7% | 9.9% | 1.2% |

| Variable | Heavy-Polluting Industries | Non-Heavy-Polluting Industries |

|---|---|---|

| TFP | TFP | |

| ESGP | 0.009 *** | 0.006 |

| (2.602) | (1.622) | |

| Size | 0.550 *** | 0.595 *** |

| (46.231) | (54.101) | |

| SOE | −0.017 | −0.045 * |

| (−0.711) | (−1.915) | |

| ListAge | 0.015 | 0.046 *** |

| (0.734) | (2.650) | |

| Lev | −0.078 | 0.253 *** |

| (−1.562) | (5.130) | |

| ROA | 0.597 *** | 0.767 *** |

| (5.530) | (7.730) | |

| Cashflow | 0.354 *** | 0.329 *** |

| (5.456) | (4.844) | |

| Indep | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| (0.092) | (1.305) | |

| ATO | 0.894 *** | 1.004 *** |

| (36.462) | (37.526) | |

| YearFE | Yes | Yes |

| FirmFE | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −4.555 *** | −5.763 *** |

| (−16.760) | (−23.916) | |

| F-values | 401.992 | 681.821 |

| Observations | 4154 | 7635 |

| R-squared | 0.971 | 0.963 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Z.; He, B. Merging Economic Aspirations with Sustainability: ESG and the Evolution of the Corporate Development Paradigm in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209108

Zhang C, Zhang S, Zhou Z, He B. Merging Economic Aspirations with Sustainability: ESG and the Evolution of the Corporate Development Paradigm in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209108

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Changjiang, Sihan Zhang, Zhepeng Zhou, and Bing He. 2025. "Merging Economic Aspirations with Sustainability: ESG and the Evolution of the Corporate Development Paradigm in China" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209108

APA StyleZhang, C., Zhang, S., Zhou, Z., & He, B. (2025). Merging Economic Aspirations with Sustainability: ESG and the Evolution of the Corporate Development Paradigm in China. Sustainability, 17(20), 9108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209108