Sustainable Cities and Quality of Life: A Multi-Criteria Approach for Evaluating Perceived Satisfaction with Public Administration

Abstract

1. Introduction

- MQ1: How can missing survey data be incorporated into B-TOPSIS to better handle the resulting uncertainty?

- MQ2: How can the B-TOPSIS framework be extended to ensure robust and reliable comparison of simulated results?

- MQ3: How can the B-TOPSIS result be organized to enable cross-survey and temporal comparisons of subjective assessments while maintaining methodological consistency across different data collections?

- Q1: How do European cities rank in terms of perceived satisfaction with local public administration in 2023?

- Q2: What are the key differences in perceived satisfaction with public administration across European cities in 2023?

- Q3: Does city size influence perceived satisfaction with public administration in European cities in 2023?

- Q4: Are there inter-regional variations in perceived satisfaction with public administration across European cities in 2023?

- Q5: Are there intra-country differences in perceived satisfaction with public administration across European cities in 2023?

- Q6: How has the level of satisfaction with local administration changed in the surveyed cities between 2019 and 2023?

- It introduces a novel robustness protocol to the B-TOPSIS method based on Monte Carlo simulation and enriches the rating and ranking stage through the use of Almost First-Order Stochastic Dominance (AFSD), which summarizes the results obtained under an assumed set of reliable ordinal value functions.

- It offers an additional analytical phase that allows for the verification of relationships between ratings obtained from different surveys, enabling longitudinal (temporal) analyses of changes in satisfaction with local administration.

- It applies the extended procedure to evaluate the quality of local public administration in European cities by aggregating indicators of efficiency, transparency, cost, digital accessibility, and corruption.

- It empirically tests the procedure by ranking European cities, analyzing differences in satisfaction across city sizes, regions, and countries, and comparing changes between two time periods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

- Step 1. Formulate the problem and construct the Belief Decision Matrix: Define the alternatives and criteria, then create a decision matrix using the BS model to represent respondent evaluations.

- Step 2. Normalize the BS model and build the Normalized Belief Decision Matrix.

- Step 3. Assign utility to evaluation grades and calculate the similarity between grades to form a Similarity Matrix.

- Step 4. Assign relative importance (weight) to each criterion using subjective or objective methods, ensuring the weights sum to one.

- Step 5. Determine the best and worst possible outcomes for each criterion, representing the Positive Ideal Belief Solution (PIBS) and Negative Ideal Belief Solution (NIBS).

- Step 6. Calculate Separation Measures for each alternative represented by its distance from the PIBS and NIBS using belief distance measures.

- Step 7. Calculate Relative Closeness of each alternative to the ideal solution.

- Step 8. Determine robust results using Monte-Carlo simulation.

- Step 9. Rank the objects using simulated data.

- Step 10. Verify the relationships between ratings obtained from different surveys.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. B-TOPSIS Standard Routine for Alternatives Evaluation and Cross-Surveys Comparisons

3.2. Cross-City and Cross-Country Comparisons (Q2–Q6)

3.3. Links to Quality of Life

4. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hajian, M.; Kashani, S.J. Evolution of the Concept of Sustainability. From Brundtland Report to Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G. Quality of Life and Sustainability: Toward Person–Environment Congruity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Querci, E. The Connection between the Quality of Life and Sustainable Ecological Development. Eur. Sci. J. 2017, 13, 361–375. [Google Scholar]

- Berishvili, N. Agenda 2030 and the EU on Sustainable Cities and Communities. In Implementing Sustainable Development Goals in Europe; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 150–161. ISBN 978-1-78990-997-5. [Google Scholar]

- Klopp, J.M.; Petretta, D.L. The Urban Sustainable Development Goal: Indicators, Complexity and the Politics of Measuring Cities. Cities 2017, 63, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronael, M.; Oruç Ertekin, G.D. Public Spaces for Future Cities: Mapping Urban Resilience Dimensions in Place-Based Solutions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 133, 106870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDG 11-Sustainable Cities and Communities. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=SDG_11_-_Sustainable_cities_and_communities (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Mishra, P.; Singh, G. Sustainable Smart Cities: Enabling Technologies, Energy Trends and Potential Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-33353-8. [Google Scholar]

- Trindade, E.P.; Hinnig, M.P.F.; da Costa, E.M.; Marques, J.S.; Bastos, R.C.; Yigitcanlar, T. Sustainable Development of Smart Cities: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismagiloiva, E.; Hughes, L.; Rana, N.; Dwivedi, Y. Role of Smart Cities in Creating Sustainable Cities and Communities: A Systematic Literature Review. In ICT Unbounded, Social Impact of Bright ICT Adoption; Dwivedi, Y., Ayaburi, E., Boateng, R., Effah, J., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 558, pp. 311–324. ISBN 978-3-030-20670-3. [Google Scholar]

- De Dominicis, L.; Berlingieri, F.; d’Hombres, B.; Gentile, C.; Mauri, C.; Stepanova, E.; Pontarollo, N.; European Commission (Eds.) Report on the Quality of Life in European Cities, 2023; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; ISBN 978-92-68-07783-2. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Aghion, P., Durlauf, S.N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 385–472. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Do Institutions Matter for Regional Development? Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsi, P.; de Dominics, L.; Castelli, C.; d’Hombres, B.; Montalt, V.; Pontarollo, N. Report on the Quality of Life in European Cities, 2020; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Inforegio—Quality of Life in European Cities. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/information-sources/maps/quality-of-life_en (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- El Gibari, S.; Gómez, T.; Ruiz, F. Building Composite Indicators Using Multicriteria Methods: A Review. J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 89, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; Ishizaka, A.; Tasiou, M.; Torrisi, G. On the Methodological Framework of Composite Indices: A Review of the Issues of Weighting, Aggregation, and Robustness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindén, D.; Cinelli, M.; Spada, M.; Becker, W.; Gasser, P.; Burgherr, P. A Framework Based on Statistical Analysis and Stakeholders’ Preferences to Inform Weighting in Composite Indicators. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 145, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartniczak, B.; Raszkowski, A. Implementation of the Sustainable Cities and Communities Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) in the European Union. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wątróbski, J.; Bączkiewicz, A.; Ziemba, E.; Sałabun, W. Sustainable Cities and Communities Assessment Using the DARIA-TOPSIS Method. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 83, 103926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wątróbski, J.; Bączkiewicz, A.; Ziemba, E.; Sałabun, W. Temporal VIKOR—A New MCDA Method Supporting Sustainability Assessment. In Advances in Information Systems Development; Silaghi, G.C., Buchmann, R.A., Niculescu, V., Czibula, G., Barry, C., Lang, M., Linger, H., Schneider, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 63, pp. 187–206. ISBN 978-3-031-32417-8. [Google Scholar]

- Górecka, D.; Roszkowska, E. Enhancing Spatial Analysis through Reference Multi-Criteria Methods: A Study Evaluating EU Countries in Terms of Sustainable Cities and Communities. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2025, 25, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E.; Filipowicz-Chomko, M.; Górecka, D.; Majewska, E. Sustainable Cities and Communities in EU Member States: A Multi-Criteria Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Tomaney, J. What Kind of Local and Regional Development and for Whom? Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefmański, B. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Synthetic Measure for Ordinal Data. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Section on Classification and Data Analysis of the Polish Statistical Association, Szczecin, Poland, 18–20 September 2019; pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jefmański, B.; Roszkowska, E.; Kusterka-Jefmańska, M. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Synthetic Measure on the Basis of Survey Responses and Aggregated Ordinal Data. Entropy 2021, 23, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusterka-Jefmańska, M.; Roszkowska, E.; Jefmański, B. The Intuitionistic Fuzzy Synthetic Measure in a Dynamic Analysis of the Subjective Quality of Life of Citizens of European Cities. Econ. Environ. 2024, 88, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusterka-Jefmańska, M.; Jefmański, B.; Roszkowska, E. Application of the Intuitionistic Fuzzy Synthetic Measure in the Subjective Quality of Life Measurement Based on Survey Data. In Modern Classification and Data Analysis, Proceedings of the SKAD 2021, Poland, Online, 8–10 September 2021; Jajuga, K., Dehnel, G., Walesiak, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 243–261. [Google Scholar]

- Roszkowska, E.; Filipowicz-Chomko, M.; Kusterka-Jefmańska, M.; Jefmański, B. The Impact of the Intuitionistic Fuzzy Entropy-Based Weights on the Results of Subjective Quality of Life Measurement Using Intuitionistic Fuzzy Synthetic Measure. Entropy 2023, 25, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszkowska, E.; Kusterka-Jefmańska, M.; Jefmański, B. Intuitionistic Fuzzy TOPSIS as a Method for Assessing Socioeconomic Phenomena on the Basis of Survey Data. Entropy 2021, 23, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszkowska, E.; Wachowicz, T. Smart Cities and Resident Well-Being: Using the BTOPSIS Method to Assess Citizen Life Satisfaction in European Cities. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, K. Smart City Logistics on Cloud Computing Model. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 151, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziller, C.; Andreß, H.-J. Quality of Local Government and Social Trust in European Cities. Urban Stud. 2022, 59, 1909–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J. E-Participation, Transparency, and Trust in Local Government. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, D.A. del The Institutional, Economic and Social Determinants of Local Government Transparency. J. Econ. Policy Reform. 2013, 16, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, R. Using Fees and Charges-Cost Recovery in Local Government. Local Gov. Res. Ser. Rep. 2012, 3, 6–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rias-Aceituno, J.V.; García-Aánchez, I.M.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, L. Electronic Administration Styles and Their Determinants. Evidence from Spanish Local Governments. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2014, 10, 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, P.A.; Czekaj, M.; Salachna, T. Digital Accessibility of Social Welfare Institutions. Rozpr. Społeczne Soc. Diss. 2024, 18, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibov, N.; Auchynnikava, A.; Luo, R.; Fan, L. The Importance of Institutional Trust in Explaining Life-Satisfaction: Lessons From the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Probl. Econ. Transit. 2022, 63, 401–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, M.S.; Sobis, I. Trust in the Local Administration: A Comparative Study between Capitals and Non-Capital Cities in Europe. NISPAcee J. Public. Adm. Policy 2018, 11, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründler, K.; Potrafke, N. Corruption and Economic Growth: New Empirical Evidence. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2019, 60, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, N.; Dijkstra, L.; Lapuente, V. Regional Governance Matters: Quality of Government within European Union Member States. Reg. Stud. 2023, 48, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, N.; Lapuente, V.; Annoni, P. Measuring Quality of Government in EU Regions across Space and Time. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 1925–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesen, P.T.; Sønderskov, K.M. Quality of Government and Social Trust. In The Oxford Handbook of the Quality of Government; Bågenholm, A., Bauhr, M., Grimes, M., Rothstein, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-0-19-885821-8. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, L.; Gallego-Álvarez, I. The Relationship between Political Factors and the Development of E–Participatory Government. Inf. Soc. 2011, 27, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelzadeh, A.; Lundberg, E. The Longitudinal Link between Institutional and Community Trust in a Local Context—Findings from a Swedish Panel Study. Local Gov. Stud. 2024, 51, 747–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapley, L.S.; Shubik, M. Pure Competition, Coalitional Power, and Fair Division. Int. Econ. Rev. 1969, 10, 337–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiffa, H.; Richardson, J.; Metcalfe, D. Negotiation Analysis: The Science and Art of Collaborative Decision Making; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-674-00890-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, X.; Fernandez, I.C.; Guo, J.; Wilson, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, B.; Wu, J. When to Use What: Methods for Weighting and Aggregating Sustainability Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 81, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decancq, K.; Lugo, M.A. Weights in Multidimensional Indices of Wellbeing: An Overview: Econometric Reviews. Econom. Rev. 2013, 32, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.C. A Review of Exploratory Factor Analysis Decisions and Overview of Current Practices: What We Are Doing and How Can We Improve? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2016, 32, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, Y.-W.; Tang, D.-W.; Chen, Y.-W. TOPSIS with Belief Structure for Group Belief Multiple Criteria Decision Making. Int. J. Autom. Comput. 2010, 7, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M. Almost Stochastic Dominance and Efficient Investment Sets. Am. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 2, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S. Decision Theory: An Introduction to the Mathematics of Rationality; Halsted Press: Sydney, Australia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Michalska, E.; Dudzińska-Baryła, R. Comparison of the Valuations of Alternatives Based on Cumulative Prospect Theory and Almost Stochastic Dominance. Oper. Res. Decis. 2012, 22, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczak, A.; Kalinowski, S. A Fuzzy Hybrid MCDM Approach to the Evaluation of Subjective Household Poverty. Stat. Transit. New Ser. 2025, 26, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E. A Comprehensive Exploration of Hellwig’s Taxonomic Measure of Development and Its Modifications—A Systematic Review of Algorithms and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, A.; Just, M. A Complex MCDM Procedure for the Assessment of Economic Development of Units at Different Government Levels. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Raan, A.F.J. Urban Scaling in Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands: Relation with Governance Structures. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.03004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, D.; Setzer, R. The Impact of Regional Institutional Quality on Economic Growth and Resilience in the EU; The European Central Bank: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ketterer, T.D.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Institutions vs. ‘first-nature’ Geography: What Drives Economic Growth in Europe’s Regions? Pap. Reg. Sci. 2018, 97, S25–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, N.; Lapuente, V. Why Do Some Regions in Europe Have a Higher Quality of Government? J. Politics 2013, 75, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Di Cataldo, M. Quality of Government and Innovative Performance in the Regions of Europe. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 15, 673–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, S.; Bostancı, S.H. The Efficiency of E-Government Portal Management from a Citizen Perspective: Evidences from Turkey. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 18, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thissen, M.; Van Oort, F.; McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R.; Husby, T. The Implications of Brexit for UK and EU Regional Competitiveness. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 96, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, B.; Schäfer, F.-S.; Aristovnik, A.; Kovač, P.; Ravšelj, D. The Impact of Digitalized Communication on the Effectiveness of Local Administrative Authorities — Findings from Central European Countries in the COVID-19 Crisis. J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 93, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Digital Decade—Policy Programme. The Yearly Editions of the Digital Decade Report. 2025. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-decade-2025-country-reports (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Kuhlmann, S.; Wollmann, H.; Reiter, R. Introduction to Comparative Public Administration: Administrative Systems and Reforms in Europe, 3rd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; ISBN 978-1-0353-0247-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno, M.; Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B.; Abate, F. The Role of Institutional and Operational Factors in the Digitalization of Large Local Governments: Insights from Italy. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2024, 38, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węziak-Białowolska, D. Quality of Life in Cities–Empirical Evidence in Comparative European Perspective. Cities 2016, 58, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolás-Martínez, C.; Pérez-Cárceles, M.C.; Riquelme-Perea, P.J.; Verde-Martín, C.M. Are Cities Decisive for Life Satisfaction? A Structural Equation Model for the European Population. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 174, 1025–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos-García, M.J.; López-López, V.; Vila-Vázquez, G.; González, X.P. Governance, Quality of Life and City Performance: A Study Based on Artificial Intelligence. J. Comput. Soc. Sc. 2025, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L. Metagovernance for Sustainability: A Framework for Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-351-25060-3. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics of Respondents | Category | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47.12% |

| Female | 52.88% | |

| Age | 15–19 | 5.04% |

| 20–24 | 10.54% | |

| 25–34 | 17.55% | |

| 35–44 | 16.63% | |

| 45–54 | 14.64% | |

| 55–64 | 13.94% | |

| 65–74 | 13.69% | |

| 75+ | 7.96% | |

| Don’t know/No Answer/Refuses | 0.00% | |

| Level of Education | Less than Primary education | 0.30% |

| Primary education | 1.89% | |

| Lower secondary education | 15.22% | |

| Upper secondary education | 37.97% | |

| Post-secondary non-tertiary education | 8.18% | |

| Short-cycle tertiary education | 8.92% | |

| Bachelor or equivalent | 14.75% | |

| Master or equivalent | 10.53% | |

| Doctoral or equivalent | 1.65% | |

| Don’t know/No Answer/Refuses | 0.60% |

| Question | Criterion | References |

|---|---|---|

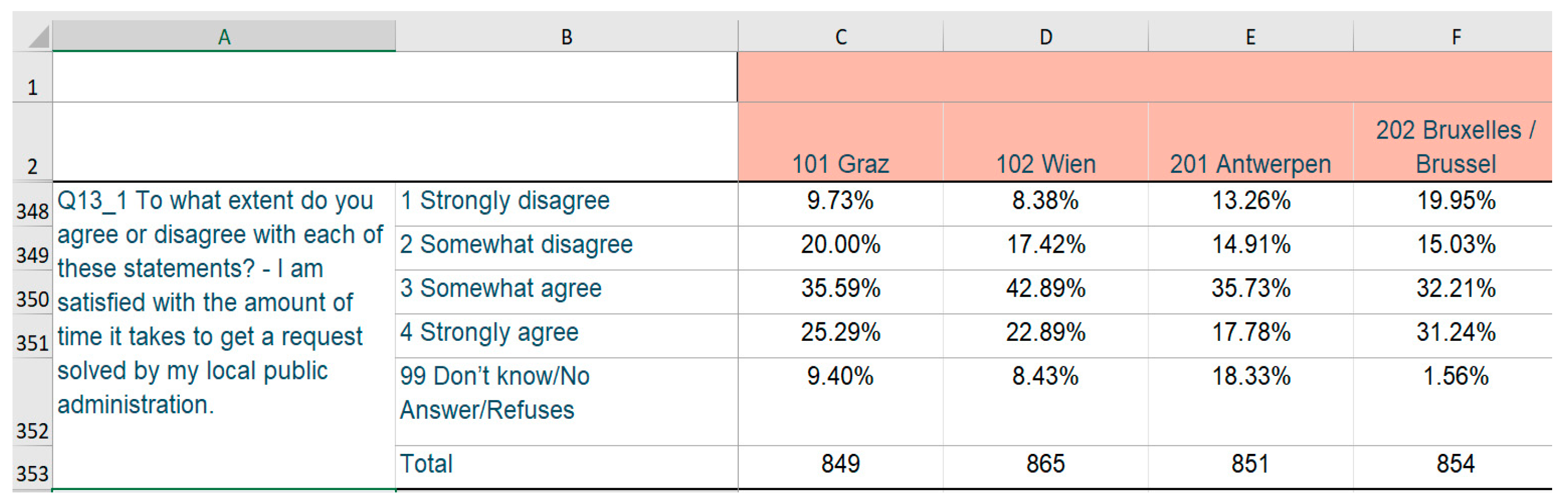

| Q1: I am satisfied with the amount of time it takes to get a request solved by my local public administration. | C1: Efficiency–the time required to resolve administrative requests. | [33,34] |

| Q2: The procedures used by my local public administration are straightforward and easy to understand. | C2: Transparency–clarity and simplicity of administrative procedures. | [35,36,37] |

| Q3: The fees charged by my local public administration are reasonable. | C3: Costs–fairness and reasonableness of fees charged by local authorities. | [37] |

| Q4: Information and services of my local public administration can be easily accessed online. | C4: Digital accessibility–ease of accessing public services online. | [38,39] |

| Q5: There is corruption in my local public administration. | C5: Trust–perception of corruption within local institutions. | [34,40,41,42,43,44,45] |

| Response Options | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Disagree | 2.83% | 3.65% | 2.36% | 0.73% | 31.20% |

| Somewhat Disagree | 11.75% | 19.71% | 17.06% | 8.46% | 13.46% |

| Somewhat Agree | 42.79% | 43.81% | 51.44% | 36.02% | 13.46% |

| Strongly Agree | 27.74% | 26.77% | 25.92% | 45.12% | 3.56% |

| 99. Don’t know/No Answer/Refuses | 14.89% | 6.06% | 3.22% | 9.67% | 15.47% |

| Satisfaction scale | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Very unsatisfied | 2.83% | 3.65% | 2.36% | 0.73% | 3.56% |

| Rather unsatisfied | 11.75% | 19.71% | 17.06% | 8.46% | 13.46% |

| Rather satisfied | 42.79% | 43.81% | 51.44% | 36.02% | 36.31% |

| Very satisfied | 27.74% | 26.77% | 25.92% | 45.12% | 31.20% |

| 99. Don’t know/No Answer/Refuses | 14.89% | 6.06% | 3.22% | 9.67% | 15.47% |

| No. | City | Country | City Group | Population | Average B-TOPSIS Score (Ri) | SD | Rank FSD | Rank AFSD (0.25) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Aalborg | DK | Northern MS | 1 | 0.414 | 0.712 | 0.643 | 0.022 | 4 | 7 |

| 2. | Amsterdam | NL | Western MS | 4 | 0.458 | 0.652 | 0.594 | 0.019 | 14 | 19 |

| 3. | Ankara | TR | Other | 5 | 0.388 | 0.684 | 0.644 | 0.017 | 3 | 5 |

| 4. | Antalya | TR | Other | 4 | 0.379 | 0.703 | 0.659 | 0.018 | 2 | 3 |

| 5. | Antwerpen | BE | Western MS | 3 | 0.469 | 0.642 | 0.584 | 0.021 | 18 | 23 |

| 6. | Athens | EL | Southern MS | 4 | 0.607 | 0.505 | 0.446 | 0.018 | 49 | 61 |

| 7. | Barcelona | ES | Southern MS | 4 | 0.513 | 0.571 | 0.527 | 0.017 | 41 | 49 |

| 8. | Belfast | UK | Other | 2 | 0.482 | 0.640 | 0.577 | 0.021 | 22 | 27 |

| 9. | Belgrade | RS | Western Balkans | 4 | 0.635 | 0.464 | 0.410 | 0.015 | 52 | 65 |

| 10. | Berlin | DE | Western MS | 4 | 0.557 | 0.595 | 0.517 | 0.021 | 42 | 51 |

| 11. | Białystok | PL | Eastern MS | 2 | 0.496 | 0.683 | 0.584 | 0.025 | 15 | 23 |

| 12. | Bologna | IT | Southern MS | 2 | 0.539 | 0.630 | 0.540 | 0.023 | 36 | 45 |

| 13. | Bordeaux | FR | Western MS | 3 | 0.456 | 0.661 | 0.598 | 0.020 | 13 | 17 |

| 14. | Braga | PT | Southern MS | 1 | 0.576 | 0.638 | 0.524 | 0.023 | 40 | 49 |

| 15. | Bratislava | SK | Eastern MS | 2 | 0.522 | 0.631 | 0.547 | 0.022 | 34 | 43 |

| 16. | Bruxelles | BE | Western MS | 4 | 0.425 | 0.671 | 0.617 | 0.019 | 6 | 11 |

| 17. | Bucharest | RO | Eastern MS | 4 | 0.550 | 0.571 | 0.500 | 0.018 | 44 | 54 |

| 18. | Budapest | HU | Eastern MS | 4 | 0.464 | 0.637 | 0.589 | 0.019 | 16 | 22 |

| 19. | Burgas | BG | Eastern MS | 1 | 0.500 | 0.605 | 0.545 | 0.017 | 33 | 43 |

| 20. | Cardiff | UK | Other | 2 | 0.450 | 0.686 | 0.615 | 0.022 | 8 | 12 |

| 21. | Cluj-Napoca | RO | Eastern MS | 2 | 0.457 | 0.672 | 0.596 | 0.019 | 13 | 18 |

| 22. | Copenhagen | DK | Northern MS | 4 | 0.410 | 0.711 | 0.644 | 0.021 | 4 | 6 |

| 23. | Diyarbakir | TR | Other | 4 | 0.523 | 0.553 | 0.512 | 0.017 | 42 | 52 |

| 24. | Dortmund | DE | Western MS | 3 | 0.538 | 0.627 | 0.540 | 0.022 | 36 | 45 |

| 25. | Dublin | IE | Western MS | 4 | 0.465 | 0.670 | 0.597 | 0.022 | 13 | 18 |

| 26. | Essen | DE | Western MS | 3 | 0.499 | 0.647 | 0.571 | 0.021 | 26 | 32 |

| 27. | Gdańsk | PL | Eastern MS | 2 | 0.487 | 0.674 | 0.584 | 0.023 | 17 | 23 |

| 28. | Genève | CH | EFTA | 2 | 0.441 | 0.698 | 0.620 | 0.022 | 6 | 10 |

| 29. | Glasgow | UK | Other | 4 | 0.486 | 0.641 | 0.575 | 0.020 | 23 | 28 |

| 30. | Graz | AT | Western MS | 2 | 0.430 | 0.703 | 0.629 | 0.022 | 5 | 8 |

| 31. | Groningen | NL | Western MS | 1 | 0.416 | 0.696 | 0.645 | 0.020 | 3 | 4 |

| 32. | Hamburg | DE | Western MS | 4 | 0.503 | 0.668 | 0.574 | 0.023 | 20 | 29 |

| 33. | Helsinki | FI | Northern MS | 4 | 0.488 | 0.642 | 0.572 | 0.021 | 24 | 31 |

| 34. | Heraklion | EL | Southern MS | 1 | 0.598 | 0.502 | 0.456 | 0.015 | 48 | 60 |

| 35. | Istanbul | TR | Other | 5 | 0.503 | 0.580 | 0.536 | 0.017 | 37 | 47 |

| 36. | Košice | SK | Eastern MS | 1 | 0.504 | 0.644 | 0.561 | 0.021 | 28 | 34 |

| 37. | Kraków | PL | Eastern MS | 3 | 0.520 | 0.635 | 0.553 | 0.022 | 30 | 37 |

| 38. | Lefkosia | CY | Southern MS | 1 | 0.494 | 0.622 | 0.561 | 0.018 | 27 | 34 |

| 39. | Leipzig | DE | Western MS | 3 | 0.525 | 0.653 | 0.561 | 0.024 | 28 | 34 |

| 40. | Liège | BE | Western MS | 2 | 0.433 | 0.671 | 0.614 | 0.019 | 10 | 13 |

| 41. | Lille | FR | Western MS | 3 | 0.481 | 0.637 | 0.576 | 0.021 | 23 | 28 |

| 42. | Lisboa | PT | Southern MS | 4 | 0.597 | 0.588 | 0.493 | 0.022 | 44 | 56 |

| 43. | Ljubljana | SI | Eastern MS | 2 | 0.519 | 0.630 | 0.549 | 0.021 | 34 | 42 |

| 44. | London | UK | Other | 5 | 0.503 | 0.626 | 0.558 | 0.021 | 29 | 35 |

| 45. | Luxembourg | LU | Western MS | 1 | 0.388 | 0.745 | 0.662 | 0.022 | 2 | 2 |

| 46. | Madrid | ES | Southern MS | 5 | 0.504 | 0.596 | 0.542 | 0.019 | 35 | 44 |

| 47. | Málaga | ES | Southern MS | 3 | 0.494 | 0.603 | 0.552 | 0.018 | 31 | 37 |

| 48. | Malmö | SE | Northern MS | 2 | 0.439 | 0.665 | 0.616 | 0.020 | 7 | 12 |

| 49. | Manchester | UK | Other | 4 | 0.460 | 0.665 | 0.601 | 0.021 | 12 | 16 |

| 50. | Marseille | FR | Western MS | 3 | 0.512 | 0.595 | 0.534 | 0.018 | 38 | 48 |

| 51. | Miskolc | HU | Eastern MS | 1 | 0.474 | 0.637 | 0.584 | 0.019 | 18 | 23 |

| 52. | München | DE | Western MS | 4 | 0.477 | 0.668 | 0.591 | 0.022 | 14 | 21 |

| 53. | Napoli | IT | Southern MS | 4 | 0.645 | 0.481 | 0.422 | 0.019 | 51 | 63 |

| 54. | Oslo | NO | EFTA | 3 | 0.510 | 0.614 | 0.549 | 0.020 | 33 | 41 |

| 55. | Ostrava | CZ | Eastern MS | 2 | 0.512 | 0.634 | 0.551 | 0.020 | 32 | 39 |

| 56. | Oulu | FI | Northern MS | 1 | 0.493 | 0.648 | 0.573 | 0.022 | 23 | 30 |

| 57. | Oviedo | ES | Southern MS | 1 | 0.533 | 0.560 | 0.511 | 0.018 | 43 | 53 |

| 58. | Palermo | IT | Southern MS | 3 | 0.683 | 0.467 | 0.402 | 0.021 | 52 | 66 |

| 59. | Paris | FR | Western MS | 5 | 0.470 | 0.639 | 0.582 | 0.019 | 19 | 24 |

| 60. | Piatra Neamţ | RO | Eastern MS | 1 | 0.504 | 0.623 | 0.554 | 0.020 | 30 | 36 |

| 61. | Podgorica | ME | Western Balkans | 1 | 0.581 | 0.525 | 0.464 | 0.016 | 47 | 58 |

| 62. | Praha | CZ | Eastern MS | 4 | 0.535 | 0.626 | 0.537 | 0.022 | 39 | 47 |

| 63. | Rennes | FR | Western MS | 2 | 0.440 | 0.692 | 0.620 | 0.022 | 6 | 9 |

| 64. | Reykjavík | IS | EFTA | 1 | 0.543 | 0.588 | 0.520 | 0.020 | 41 | 50 |

| 65. | Riga | LV | Eastern MS | 3 | 0.593 | 0.525 | 0.463 | 0.018 | 47 | 59 |

| 66. | Roma | IT | Southern MS | 4 | 0.682 | 0.453 | 0.396 | 0.018 | 53 | 67 |

| 67. | Rostock | DE | Western MS | 1 | 0.518 | 0.664 | 0.568 | 0.024 | 25 | 33 |

| 68. | Rotterdam | NL | Western MS | 4 | 0.459 | 0.647 | 0.593 | 0.020 | 14 | 20 |

| 69. | Skopje | MK | Western Balkans | 2 | 0.629 | 0.463 | 0.414 | 0.014 | 51 | 64 |

| 70. | Sofia | BG | Eastern MS | 4 | 0.547 | 0.555 | 0.496 | 0.017 | 45 | 55 |

| 71. | Stockholm | SE | Northern MS | 4 | 0.490 | 0.646 | 0.579 | 0.021 | 21 | 25 |

| 72. | Strasbourg | FR | Western MS | 2 | 0.447 | 0.681 | 0.611 | 0.022 | 11 | 15 |

| 73. | Tallinn | EE | Eastern MS | 2 | 0.519 | 0.631 | 0.550 | 0.021 | 32 | 40 |

| 74. | Torino | IT | Southern MS | 3 | 0.606 | 0.551 | 0.475 | 0.021 | 46 | 57 |

| 75. | Tyneside conurbation | UK | Other | 3 | 0.485 | 0.641 | 0.578 | 0.021 | 21 | 26 |

| 76. | Valletta | MT | Southern MS | 2 | 0.413 | 0.696 | 0.645 | 0.021 | 3 | 4 |

| 77. | Verona | IT | Southern MS | 2 | 0.570 | 0.616 | 0.519 | 0.023 | 42 | 50 |

| 78. | Vilnius | LT | Eastern MS | 3 | 0.519 | 0.636 | 0.552 | 0.021 | 30 | 38 |

| 79. | Warszawa | PL | Eastern MS | 4 | 0.537 | 0.627 | 0.539 | 0.023 | 36 | 46 |

| 80. | Wien | AT | Western MS | 4 | 0.448 | 0.696 | 0.614 | 0.023 | 9 | 14 |

| 81. | Zagreb | HR | Eastern MS | 3 | 0.632 | 0.486 | 0.425 | 0.018 | 50 | 62 |

| 82. | Zürich | CH | EFTA | 3 | 0.386 | 0.762 | 0.678 | 0.024 | 1 | 1 |

| Class | 2019 Survey | 2023 Survey |

|---|---|---|

| High | Aalborg, Amsterdam, Antalya, Bordeaux, Bruxelles Cardiff, Copenhagen, Dublin, Genève, Glasgow, Graz, Groningen, Liège, London, Luxembourg, Malmö, Manchester, Miskolc, München, Rennes, Rotterdam, Tyneside conurbation, Valletta, Wien, Zürich | Aalborg, Ankara, Antalya, Bruxelles, Cardiff, Copenhagen, Genève, Graz, Groningen, Liège, Luxembourg, Malmö, Rennes, Strasbourg, Valletta, Wien, Zürich |

| Medium | Ankara, Antwerpen, Athens, Barcelona, Belfast, Belgrade, Berlin, Białystok, Bologna, Braga, Bratislava, Bucharest, Budapest, Burgas, Cluj-Napoca, Diyarbakir, Dortmund, Essen, Gdańsk, Hamburg, Helsinki, Heraklion, Istanbul, Košice, Kraków, Lefkosia, Leipzig, Lille, Lisboa, Ljubljana, Madrid, Málaga, Marseille, Napoli, Oslo, Ostrava, Oulu, Oviedo, Paris, Piatra Neamţ, Podgorica, Praha, Reykjavík, Riga, Rostock, Skopje, Sofia, Stockholm, Strasbourg, Tallinn, Torino, Verona, Vilnius, Warszawa, Zagreb | Amsterdam, Antwerpen, Athens, Barcelona, Belfast, Belgrade, Berlin, Białystok, Bologna, Bordeaux, Braga, Bratislava, Bucharest, Budapest, Burgas, Cluj-Napoca, Diyarbakir, Dortmund, Dublin, Essen, Gdańsk, Glasgow, Hamburg, Helsinki, Heraklion, Istanbul, Košice, Kraków, Lefkosia, Leipzig, Lille, Lisboa, Ljubljana, London, Madrid, Málaga, Manchester, Marseille, Miskolc, München, Napoli, Oslo, Ostrava, Oulu, Oviedo, Paris, Piatra Neamţ, Podgorica, Praha, Reykjavík, Riga, Rostock, Rotterdam, Skopje, Sofia, Stockholm, Tallinn, Torino, Tyneside conurbation, Verona, Vilnius, Warszawa, Zagreb |

| Poor | Palermo, Roma | Palermo, Roma |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roszkowska, E.; Wachowicz, T.; Michalska, E. Sustainable Cities and Quality of Life: A Multi-Criteria Approach for Evaluating Perceived Satisfaction with Public Administration. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210106

Roszkowska E, Wachowicz T, Michalska E. Sustainable Cities and Quality of Life: A Multi-Criteria Approach for Evaluating Perceived Satisfaction with Public Administration. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210106

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoszkowska, Ewa, Tomasz Wachowicz, and Ewa Michalska. 2025. "Sustainable Cities and Quality of Life: A Multi-Criteria Approach for Evaluating Perceived Satisfaction with Public Administration" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210106

APA StyleRoszkowska, E., Wachowicz, T., & Michalska, E. (2025). Sustainable Cities and Quality of Life: A Multi-Criteria Approach for Evaluating Perceived Satisfaction with Public Administration. Sustainability, 17(22), 10106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210106