Regional Determinants of the Development of Short Food Supply Chains in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

- Official registers: statistical data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Chief Veterinary Inspectorate, and the State Sanitary Inspectorate covering the years 2004–2024. These data concern the number of entities operating within three forms of short food supply chains: rolniczy handel detaliczny (RHD, i.e., agricultural retail trade), działalność marginalna, lokalna i ograniczona (MOL, i.e., marginal, local, and restricted activity), and direct sales (SB). Table 1 presents the number of entities engaged in SB, MOL, and RHD in Poland from 2004 to 2024.

| Year | SB | MOL | RHD | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 16,178 | 2229 | 22,449 | 40,856 |

| 2023 | 16,492 | 2353 | 22,237 | 41,082 |

| 2022 | 15,264 | 2339 | 18,040 | 35,643 |

| 2021 | 14,576 | 2291 | 15,343 | 32,210 |

| 2020 | 13,613 | 2216 | 12,212 | 28,041 |

| 2019 | 11,630 | 2284 | 7713 | 21,627 |

| 2018 | 10,020 | 2241 | 3271 | 15,532 |

| 2017 | 9570 | 2264 | 1633 | 13,467 |

| 2016 | 8688 | 2253 | - | 10,941 |

| 2015 | 7678 | 2203 | - | 9881 |

| 2014 | 7065 | 2117 | - | 9182 |

| 2013 | 6466 | 2042 | - | 8508 |

| 2012 | 5856 | 1920 | - | 7776 |

| 2011 | 5139 | 1867 | - | 7006 |

| 2010 | 4271 | 1817 | - | 6088 |

| 2009 | 3791 | 1363 | - | 5154 |

| 2008 | 2758 | 1167 | - | 3925 |

| 2007 | 1790 | 906 | - | 2696 |

| 2006 | 847 | - | - | 847 |

| 2005 | 709 | - | - | 709 |

| 2004 | 610 | - | - | 610 |

- Qualitative research: in-depth interviews and surveys conducted in 2023 across all 16 provinces, involving employees of regional marshal offices (provincial government offices), agricultural departments, and agricultural advisory centers.The qualitative component of the study comprised 32 structured interviews and 32 survey responses collected between June and October 2023 across all 16 Polish provinces. Respondents represented regional institutions responsible for agricultural development, including Marshal Offices and Agricultural Advisory Centres. The interview protocol addressed issues such as the functioning and evolution of SFSCs, institutional forms of support, barriers to development, and the effectiveness of regional policies (see Appendix A).

3.2. Methods of Analysis

3.3. Analytical Framework

3.4. Study Limitations

- it does not indicate causal relationships,

- it does not account for interaction effects (e.g., the simultaneous influence of agrarian structure and demand potential),

- it assumes monotonicity in relationships, which limits the detection of more complex patterns.

4. Results

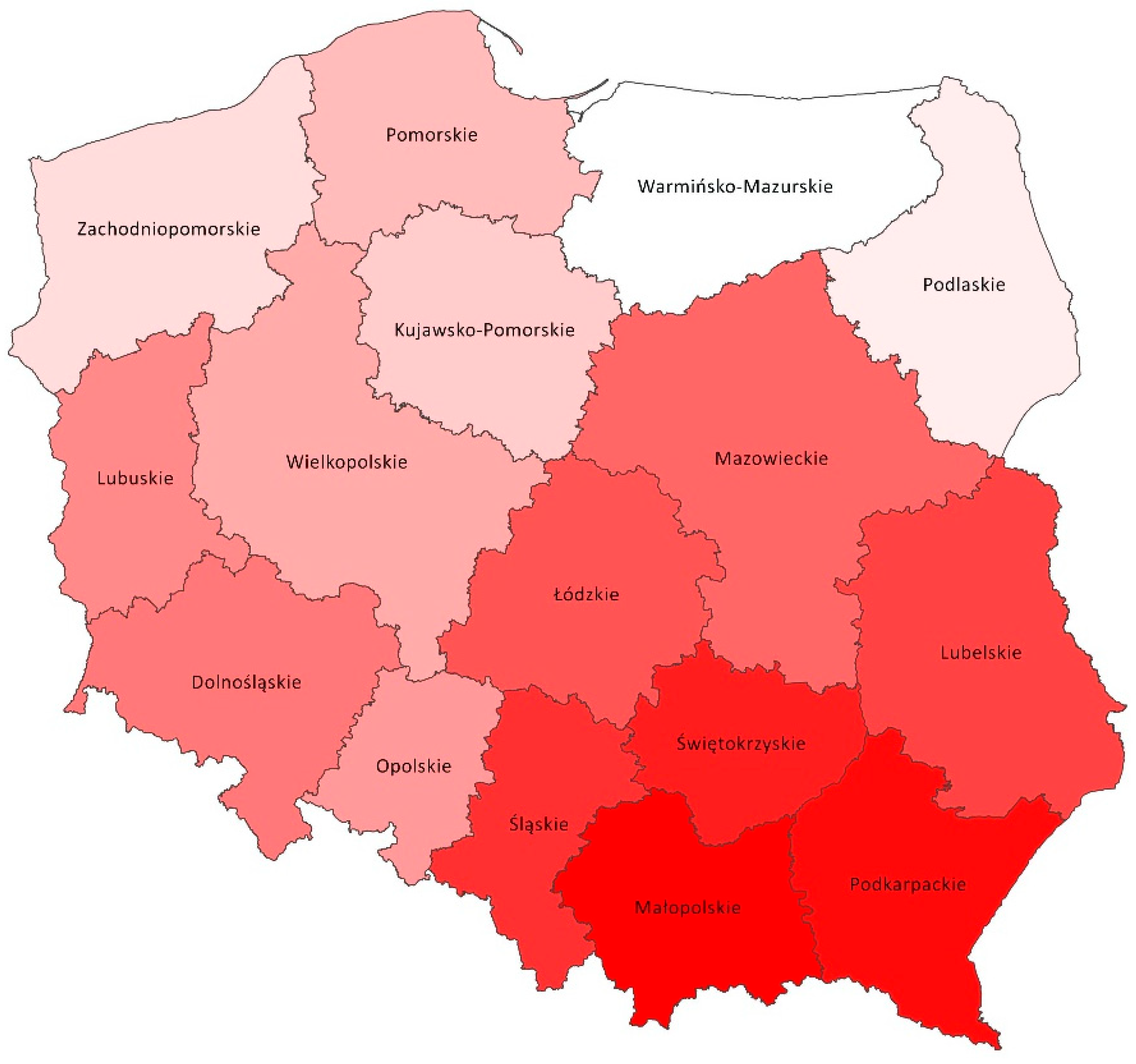

- Soil conditions: soil quality classes and complexes of agricultural suitability (18–95 points),

- Agro-climate: based on long-term meteorological data (precipitation, temperature, length of the growing season) (1–15 points),

- Water relations: based on the amount of water retained in the soil profile, taking into account granulometric composition and land relief (1–5 points),

- Land relief: based on slope classification and type of relief (0.1–5 points).

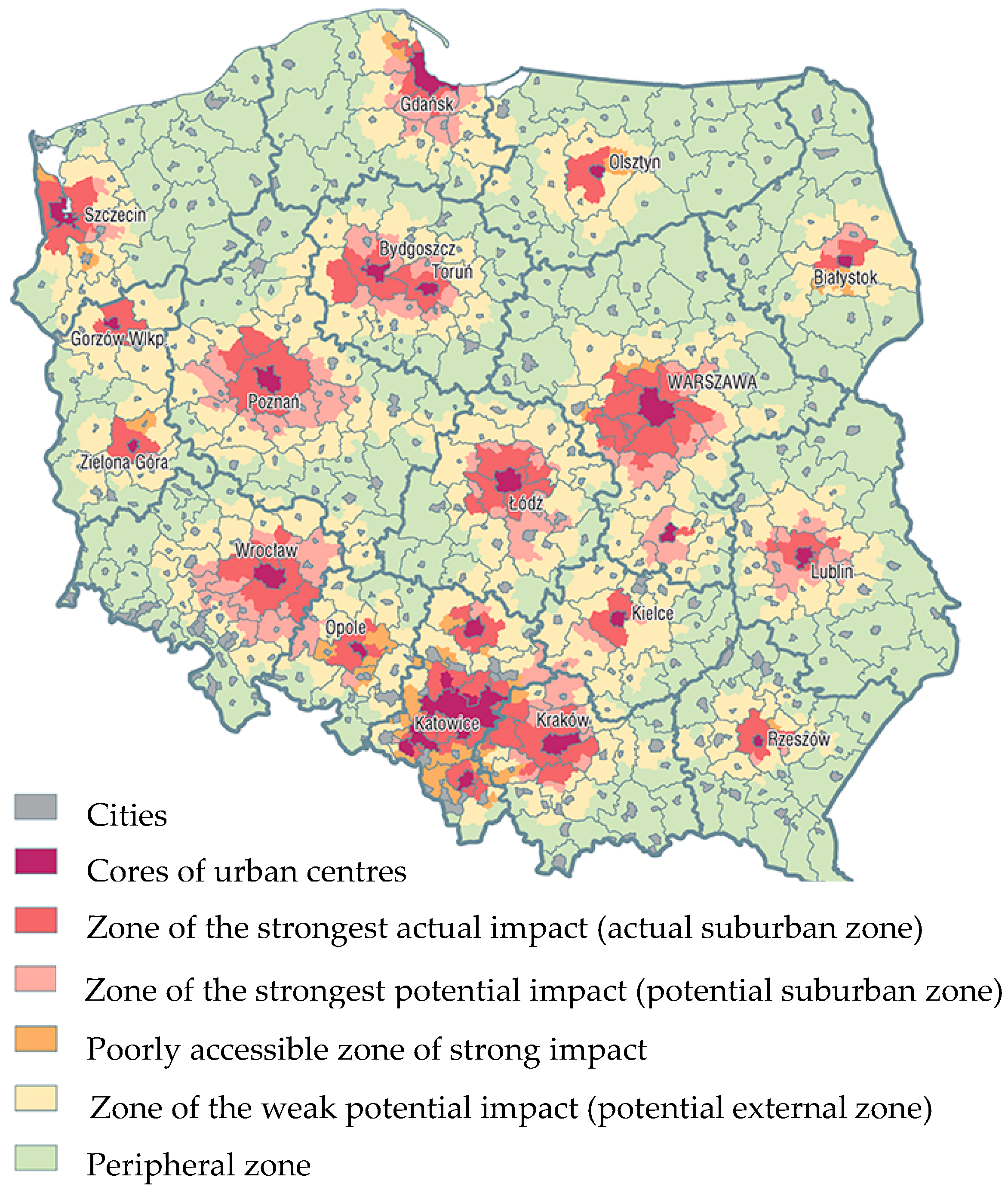

- Western and Northern Lands (ZZiP): Dolnośląskie, Opolskie, and Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeships,

- Prussian Partition: Wielkopolskie, Kujawsko-Pomorskie, Lubuskie, and Pomorskie voivodeships,

- Austrian Partition: Małopolskie, Świętokrzyskie, and Podkarpackie voivodeships,

- Russian Partition: Mazowieckie, Łódzkie, Lubelskie, and Podlaskie voivodeships,

- West Pomeranian Voivodeship (transitional area).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- How do you assess the functioning of short food supply chains (SFSCs) in your province?

- How does your institution support the development of SFSCs in the region (directly or indirectly)?

- How has the development of SFSCs evolved over time in your province?

- To what extent have these activities produced the expected (long-term) results?

- What types of support are needed to make SFSCs function more effectively in the province?

- In your opinion, which institution provides the strongest support for the development of SFSCs in the region, and which institutions should be more actively involved?

- How do you assess the functioning of the SFSC system in your province?

- How do you assess the potential for further development of SFSCs in your province?

- How do you assess the role of your institution in promoting SFSCs?

- How do you assess the level of formal cooperation among farmers?

- How do you assess the level of informal cooperation among farmers?

| Institutions | Currently support | Should support more |

| Marshal Office (regional government) | ☐ | ☐ |

| County Office | ☐ | ☐ |

| Municipality | ☐ | ☐ |

| Village Council | ☐ | ☐ |

| Agency for Restructuring and Modernisation of Agriculture | ☐ | ☐ |

| National Agricultural Advisory Centre | ☐ | ☐ |

| Regional Agricultural Advisory Centre | ☐ | ☐ |

| County Agricultural Advisory Teams | ☐ | ☐ |

| Regional Chamber of Agriculture | ☐ | ☐ |

| County Agricultural Chamber Councils | ☐ | ☐ |

| Producer associations/cooperatives | ☐ | ☐ |

| Consumer associations/cooperatives | ☐ | ☐ |

| Local Action Group (LAG) | ☐ | ☐ |

| NGOs, foundations | ☐ | ☐ |

| County Sanitary Inspectorate (SANEPID) | ☐ | ☐ |

| County Veterinary Inspectorate | ☐ | ☐ |

| Tax Office | ☐ | ☐ |

| Other (please specify): __________________________ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Barrier | Impact on SFSC development | Strong | Rather strong | Neutral | Weak |

| Production (including production costs) | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Processing | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Logistics/distribution | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Financial issues (investment, liquidity) | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Legal issues (regulations) | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Certification | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Cooperation difficulties | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Advisory services | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Market competition | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Unfair competition | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Consumers and their habits | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Lack of funds for promotion/sales development | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Lack of knowledge and skills in marketing and sales | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Other (please specify) | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

Appendix B

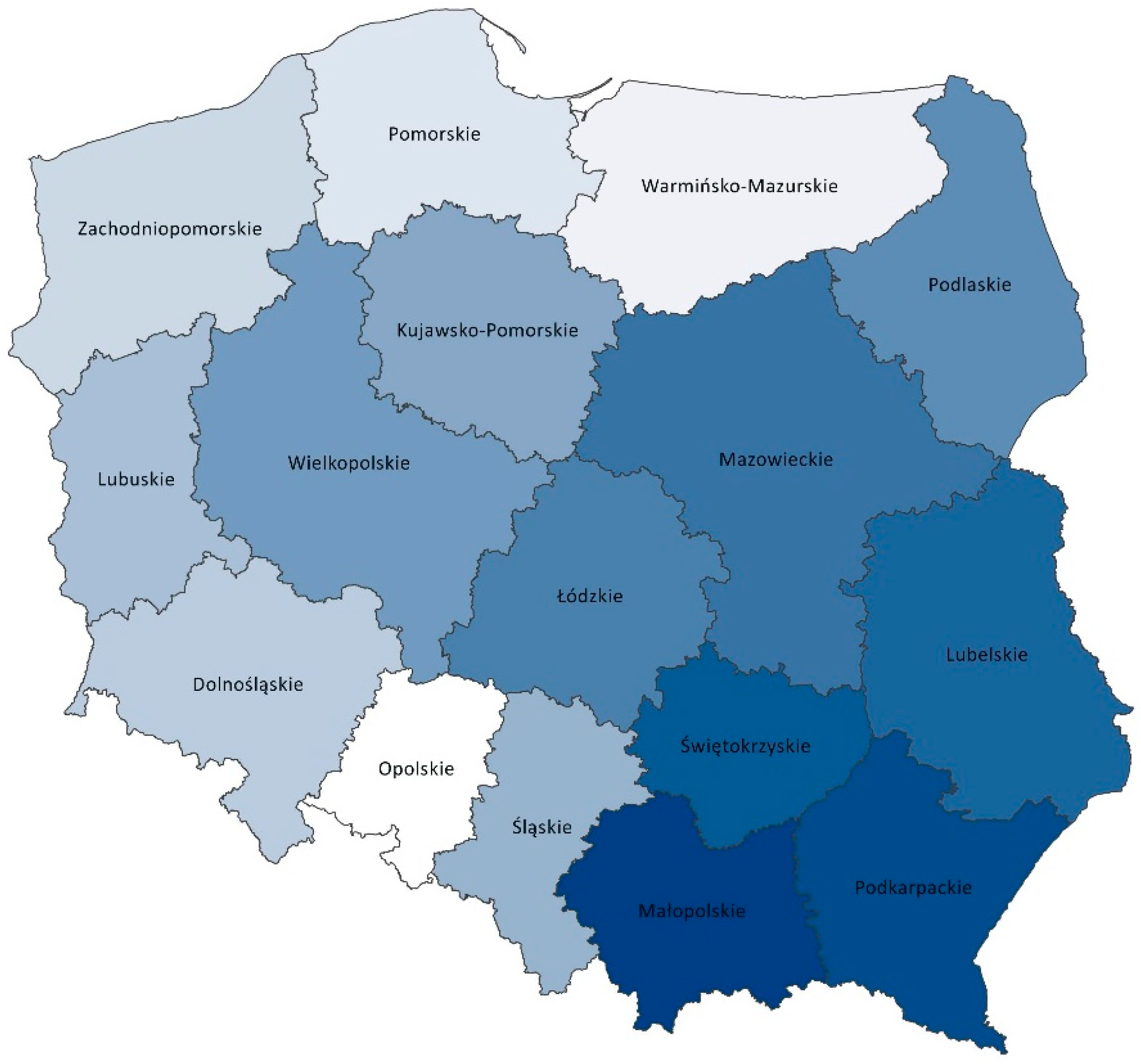

| Province | Ranking of the Number of Entities in SFSCs | Ranking of the Share of Agricultural Holdings Up to 10 Hectares | D | D2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 2 | 8 | −6 | 36 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 11 | 13 | −2 | 4 |

| Lubelskie | 9 | 5 | 4 | 16 |

| Lubuskie | 13 | 9 | 4 | 16 |

| Łódzkie | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Małopolskie | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Mazowieckie | 4 | 7 | −3 | 9 |

| Opolskie | 16 | 10 | 6 | 36 |

| Podkarpackie | 6 | 2 | 4 | 16 |

| Podlaskie | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Pomorskie | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Śląskie | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 14 | 3 | 11 | 121 |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 8 | 16 | −8 | 64 |

| Wielkopolskie | 1 | 11 | −10 | 100 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 10 | 14 | −4 | 16 |

| =440 |

| Province | Ranking of the Number of Entities in SFSCs | Index of APSV (1 = the Poorest Soils) | D | D2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 2 | 15 | 13 | 169 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 11 | 13 | 2 | 4 |

| Lubelskie | 9 | 14 | 5 | 25 |

| Lubuskie | 13 | 4 | −9 | 81 |

| Łódzkie | 7 | 3 | −4 | 16 |

| Małopolskie | 3 | 10 | 7 | 49 |

| Mazowieckie | 4 | 2 | −2 | 4 |

| Opolskie | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Podkarpackie | 6 | 12 | 6 | 36 |

| Podlaskie | 15 | 1 | −14 | 196 |

| Pomorskie | 12 | 8 | −4 | 16 |

| Śląskie | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 14 | 11 | −3 | 9 |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 8 | 7 | −1 | 1 |

| Wielkopolskie | 1 | 6 | 5 | 25 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 10 | 9 | −1 | 1 |

| =632 |

| Province | Ranking of the Number of Entities in SFSCs | Ranking of the Involvement of Institutions Supporting SFSCs | D | D2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 2 | 12 | 10 | 100 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 11 | 1 | −10 | 100 |

| Lubelskie | 9 | 8 | −1 | 1 |

| Lubuskie | 13 | 9 | −4 | 16 |

| Łódzkie | 7 | 5 | −2 | 4 |

| Małopolskie | 3 | 2 | −1 | 1 |

| Mazowieckie | 4 | 15 | 11 | 121 |

| Opolskie | 16 | 6 | −10 | 100 |

| Podkarpackie | 6 | 13 | 7 | 49 |

| Podlaskie | 15 | 3 | −12 | 144 |

| Pomorskie | 12 | 10 | −2 | 4 |

| Śląskie | 5 | 14 | 9 | 81 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 14 | 11 | −3 | 9 |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 8 | 4 | −4 | 16 |

| Wielkopolskie | 1 | 7 | 6 | 36 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 10 | 16 | 6 | 36 |

| =818 |

| Province | Ranking of the Number of Entities in SFSCs | Ranking of Dependence on Historical and Social Regional Determinants | D | D2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 2 | 12 | 10 | 100 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 11 | 9 | −2 | 4 |

| Lubelskie | 9 | 4 | −5 | 25 |

| Lubuskie | 13 | 11 | −2 | 4 |

| Łódzkie | 7 | 6 | −1 | 1 |

| Małopolskie | 3 | 1 | −2 | 4 |

| Mazowieckie | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Opolskie | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Podkarpackie | 6 | 2 | −4 | 16 |

| Podlaskie | 15 | 7 | −8 | 64 |

| Pomorskie | 12 | 14 | 2 | 4 |

| Śląskie | 5 | 10 | 5 | 25 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 14 | 3 | −11 | 121 |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 8 | 15 | 7 | 49 |

| Wielkopolskie | 1 | 8 | 7 | 49 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 10 | 13 | 3 | 9 |

| =476 |

| Province | Ranking of the Number of Entities in SFSCs | Ranking of the Population of Provincial Capitals | D | D2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 11 | 9 | −2 | 4 |

| Lubelskie | 9 | 8 | −1 | 1 |

| Lubuskie | 13 | 15 | 2 | 4 |

| Łódzkie | 7 | 4 | −3 | 9 |

| Małopolskie | 3 | 2 | −1 | 1 |

| Mazowieckie | 4 | 1 | −3 | 9 |

| Opolskie | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Podkarpackie | 6 | 12 | 6 | 36 |

| Podlaskie | 15 | 10 | −5 | 25 |

| Pomorskie | 12 | 6 | −6 | 36 |

| Śląskie | 5 | 11 | 6 | 36 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 14 | 13 | −1 | 1 |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 8 | 14 | 6 | 36 |

| Wielkopolskie | 1 | 5 | 4 | 16 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 10 | 7 | −3 | 9 |

| =224 |

References

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J. Understanding alternative food networks: Exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Food supply chain approaches: Exploring their role in rural development. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Developing quality in agro-food supply chains: A Welsh perspective. Int. Plan. Stud. 1999, 4, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D.; Hillier, D. A case study of local food and its routes to market in the UK. Br. Food J. 2004, 106, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatekassa, G.; Peterson, H.C. Market access for local food through the conventional food supply chain. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C.; Buller, H. The local food sector: A preliminary assessment of its form and impact in Gloucestershire. Br. Food J. 2003, 105, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; COM (2020) 381 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; COM (2019) 640 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Raftowicz, M. Uwarunkowania Rozwoju Krótkich Łańcuchów Dostaw Żywności; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzębowski, S.; Bourlakis, M.; Bezat-Jarzębowska, A. Short food supply chains (SFSC) as local and sustainable systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarz, K.; Raftowicz, M.; Kachniarz, M.; Dradrach, A. Back to locality? Demand potential analysis for short food supply chains. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Majewski, E.; Was, A.; Borgen, S.O.; Csillag, P.; Donati, M.; Freeman, R.; Hoang, V.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Mancini, M.; et al. Measuring the economic, environmental, and social sustainability of short food supply chains. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augère-Granier, M.-L. Short food supply chains and local food systems in the EU. In European Parliamentary Research Service Briefing; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2016; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2016/586650/EPRS_BRI(2016)586650_EN.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Crescenzi, R.; Percoco, M. Geography, Institutions and Regional Economic Performance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable food supply chains: Is shortening the answer? A literature review for a research and innovation agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.; Brunori, G. Short Food Supply Chains as Drivers of Sustainable Development. Evidence Document; FOODLINKS Project (FP7, GA No. 265287); Laboratorio di Studi Rurali Sismondi: Pisa, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Petruzzelli, M.; Ihle, R.; Colitti, S.; Vittuari, M. The role of short food supply chains in advancing the global agenda for sustainable food systems transitions. Cities 2023, 141, 104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, J. Polska Wieś 2018. Raport o Stanie Wsi; Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, A.; Stanny, M. Monitoring rozwoju obszarów wiejskich. In Etap II. Przestrzenne Zróżnicowanie Poziomu Rozwoju Społeczno-Gospodarczego Obszarów Wiejskich; Fundacja Europejski Fundusz Rozwoju Wsi Polskiej i IRWiR PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stanny, M.; Rosner, A.; Komorowski, Ł. Monitoring rozwoju obszarów wiejskich. In Etap III. Struktury Społeczno-Gospodarcze, Ich Przestrzenne Zróżnicowanie i Dynamika; Fundacja Europejski Fundusz Rozwoju Wsi Polskiej i IRWiR PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chiffoleau, Y. Les circuits courts alimentaires. In Entre Marché et Innovation Sociale; Éditions Érès: Toulouse, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kneafsey, M.; Venn, L.; Schmutz, U.; Balázs, B.; Trenchard, L.; Eyden-Wood, T.; Bos, E.; Sutton, G.; Blackett, M. Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU. A State of Play of Their Socio-Economic Characteristics; European Commission JRC: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC80420/final%20ipts%20jrc%2080420%20(online).pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Bareja-Wawryszuk, O. Determinants of spatial concentration of short food supply chains on example of marginal, localized and restricted activities in Poland. Econ. Organ. Logist. 2020, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundler, P.; Laughrea, S. The contributions of short food supply chains to territorial development: A study of three Quebec territories. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 45, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Usuga, L.; Parra-Lopez, C.; de Haro-Gimenez, T.; Carmona-Torres, C. Sustainability assessment of territorial short food supply chains versus large-scale food distribution: The case of Colombia and Spain. Land Use Policy 2023, 126, 106529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftowicz, M.; Solarz, K.; Dradrach, A. Short food supply chains as a practical implication of sustainable development ideas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S.; Hall, J. Integrating sustainable development in the supply chain: The case of life cycle assessment in oil and gas and agricultural biotechnology. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 1083–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drejerska, N.; Sobczak-Malitka, W. Nurturing sustainability and health: Exploring the role of short supply chains in the evolution of food systems—The case of Poland. Foods 2023, 12, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paciarotti, C.; Torregiani, F. The logistics of the short food supply chain: A literature review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, G.; Torjusen, H.; Laitala, K.; Tocco, B.; Biasini, B.; Csillag, P.; de Labarre, M.D.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Maj, A.; Majewski, E.; et al. Short food supply chains and their contributions to sustainability: A comparative assessment of case studies in European regions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadkam, E.; Irannezhad, E. A Comprehensive Review of Simulation Optimization Methods in Agricultural Supply Chains and Transition towards an Agent-Based Intelligent Digital Framework for Agriculture 4.0. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 143, 109930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panciszko-Szweda, B. Short Food Supply Chains as a Policy Tool for Smart and Sustainable Rural Development in the European Union. Stud. Ecol. Bioethicae 2025, 2, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Increasing returns and long-run growth. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. The origins of endogenous growth. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E. On the mechanisms of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J.; Sala-i-Martin, X. Economic Growth; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P. Geography and Trade; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.C. Identity and Control: A Structural Theory of Social Action; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chief Veterinary Inspectorate. List of Registered Establishments under Veterinary Supervision. Available online: https://www.wetgiw.gov.pl/nadzor-weterynaryjny/wykaz-zakladow-rejestrowanych (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Government of the Republic of Poland. Act on Agricultural Retail Trade of 16 November 2016; Journal of Laws 2016, Item 1969; Government of the Republic of Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2016.

- Government of the Republic of Poland. Regulation of the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development of 29 December 2006 on the Requirements for Marginal, Local and Restricted Activity; Journal of Laws 2007, No. 5, Item 38; Government of the Republic of Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2006.

- Central Statistical Office. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rolnictwo-lesnictwo/psr-2020/powszechny-spis-rolny-2020-charakterystyka-gospodarstw-rolnych-w-2020-r-,6,1.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Institute of Soil Science and Plant Cultivation (IUNG-PIB). Agricultural Production Space Valorization Index (WWRPP); IUNG-PIB: Puławy, Poland, 2023; Available online: https://www.iung.pl (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Pułaska-Turyna, B. Statystyka dla Ekonomistów; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Struś, M.; Raftowicz, M. Land concentration processes in Poland in the light of D.C. North’s development paradigm. Rozw. Reg. I Polityka Reg. 2025, 73, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Office. Population. In Size and Structure of Population and Vital Statistics in Poland by Territorial Division in 2025; Central Statistical Office: Warsaw, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Motowidlak, U. Aktywność gospodarstw rolnych w Polsce w budowaniu łańcuchów dostaw. Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2009, 8, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbery, B.; Maye, D. Alternative (shorter) food supply chains and specialist livestock products in the Scottish-English borders. Environ. Plan. A 2005, 37, 823–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Usuga, L.; de Haro-Gimenez, T.; Parra-Lopez, C. Food governance in territorial short food supply chains: Different narratives and strategies from Colombia and Spain. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 75, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struś, M.; Raftowicz, M. The sustainable development paradigm versus land concentration processes. J. Law Econ. Sociol. 2023, 85, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, E.H.; Pisa, N. Short Food Supply Chain Status and Pathway in Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Fornazier, A. Case Study of the School Feeding Program in Distrito Federal, Brazil: Building Quality in Short Food Supply Chains. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M.; Abebe, G.K.; Hartt, C.M.; Yiridoe, E.K. Consumer Perceptions about the Value of Short Food Supply Chains during COVID-19: Atlantic Canada Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, Z.; Han, J. Pains and Gains: Opportunities and Challenges for Grain Farmers to Participate in Short Supply Chains in China. Agric. Food Econ. 2025, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Range of Correlation Coefficient | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| |0.0–0.2| | very weak correlation |

| |0.2–0.4| | weak correlation |

| |0.4–0.6| | moderate correlation |

| |0.6–0.8| | strong correlation |

| Variable | Description | Type of Variable | Mean | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrarian structure | Share of farms up to 10 ha in the total number of farms | Independent | 71.4 | 48.4 | 94.2 |

| Quality of agricultural space | Average WWRPP (Agricultural Production Space Valorization Index) | Independent | 67.5 | 55.0 | 81.6 |

| Institutional involvement | Institutional support ranking (based on interviews) | Independent | 8.5 | 1 | 16 |

| Historical legacy | Degree of embeddedness of agricultural traditions (regions: historical partitions) | Independent | 8.5 | 1 | 16 |

| Demand potential | Population of provincial capital cities | Independent | 460 | 11,4000 | 1,862,402 |

| Number of SFSC entities | Registered RHD, MOL, and SB producers in 2024 | Dependent | 10,600 | 610 | 40,856 |

| Province | Number of Agricultural Holdings in Thousands | Share of Agricultural Holdings | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Up to 10 ha | 10–30 ha | 30–50 ha | 50–100 ha | Above 100 ha | Up to 10 ha | 10–30 ha | 30–50 ha | 50–100 ha | Above 100 ha | |

| Dolnośląskie | 53 | 37 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 70.5 | 19.6 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 2.8 |

| Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 60 | 33 | 18 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 54.8 | 0.0 | 7.3 | 4.1 | 1.8 |

| Lubelskie | 161 | 126 | 29 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 78.3 | 18.4 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Lubuskie | 20 | 14 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 65.0 | 32.1 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 4.3 |

| Łódzkie | 117 | 90 | 23 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 76.8 | 17.7 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Małopolskie | 127 | 119 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 94.2 | 19.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Mazowieckie | 208 | 152 | 48 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 72.9 | 20.0 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Opolskie | 25 | 17 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 64.6 | 4.7 | 6.3 | 4.8 | 2.7 |

| Podkarpackie | 114 | 107 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 92.9 | 22.8 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Podlaskie | 77 | 42 | 29 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 53.4 | 21.7 | 5.9 | 2.5 | 0.6 |

| Pomorskie | 39 | 24 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 58.1 | 5.0 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 2.7 |

| Śląskie | 50 | 43 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 85.4 | 37.6 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.7 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 80 | 69 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 87.0 | 28.7 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 43 | 20 | 15 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 48.4 | 10.4 | 8.8 | 5.9 | 3.1 |

| Wielkopolskie | 116 | 71 | 33 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 62.2 | 10.9 | 5.1 | 2.7 | 1.4 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 29 | 16 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 54.5 | 33.8 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 6.6 |

| Total | 1319 | ||||||||||

| No. | Province | Total WWRPP | Class of Agricultural Potential | Potential Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dolnośląskie | 74.9 | High | 2 |

| 2 | Kujawsko-pomorskie | 71.0 | High | 4 |

| 3 | Lubelskie | 74.1 | High | 3 |

| 4 | Lubuskie | 62.3 | Medium | 13 |

| 5 | Łódzkie | 61.9 | Medium | 14 |

| 6 | Małopolskie | 69.3 | Medium | 6 |

| 7 | Mazowieckie | 59.9 | Low | 15 |

| 8 | Opolskie | 81.6 | High | 1 |

| 9 | Podkarpackie | 70.4 | High | 5 |

| 10 | Podlaskie | 55.0 | Low | 16 |

| 11 | Pomorskie | 66.2 | Medium | 9 |

| 12 | Śląskie | 64.2 | Medium | 12 |

| 13 | Świętokrzyskie | 69.3 | Medium | 7 |

| 14 | Warmińsko-mazurskie | 66.0 | Medium | 10 |

| 15 | Wielkopolskie | 64.8 | Medium | 11 |

| 16 | Zachodniopomorskie | 67.5 | Medium | 8 |

| Aspects | Western and Northern Regions | Prussian Partition Territories | Austrian Partition Territories | Russian Partition Territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical development path | Departure from the previous development trajectory, shaped by reforms after 1989. | Institutions supporting the development of large agricultural enterprises. | Granting voting rights to peasants, with gradual consolidation of holdings. | “Land hunger,” division of farms among children, limited modernization. |

| Demographics and settlement patterns | Population shifts, internal migration, and challenges related to settlement. | Consolidation of land and regulatory frameworks. | Large settlements and a dense network of urban centers. | Small settlements with dispersed structures. |

| Farm characteristics | Small-scale farms (7–15 ha), with the emergence of larger agricultural enterprises. | Dominance of large, commercially focused, and productive farms. | Peasant-worker farms with a dual livelihood. | Prevalence of medium-sized farms, gradual reduction in smallholdings. |

| Institutions and organizations | Weakened informal structures, notable state ownership (e.g., state farms). | Well-established peasant organizations and collaborative efforts. | Early implementation of mandatory education. | Abolition of feudal obligations, limited institutional backing. |

| Social capital | A considerable proportion of state farms, with developing social cohesion. | High human and social capital, with early institutional advancements | Dual occupations (peasant-worker), promoting resilience. | Low social capital due to fragmented reforms and delayed access to education. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raftowicz, M.; Korabiewski, B. Regional Determinants of the Development of Short Food Supply Chains in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9772. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219772

Raftowicz M, Korabiewski B. Regional Determinants of the Development of Short Food Supply Chains in Poland. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9772. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219772

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaftowicz, Magdalena, and Bartosz Korabiewski. 2025. "Regional Determinants of the Development of Short Food Supply Chains in Poland" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9772. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219772

APA StyleRaftowicz, M., & Korabiewski, B. (2025). Regional Determinants of the Development of Short Food Supply Chains in Poland. Sustainability, 17(21), 9772. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219772