Abstract

This study examines how mindful consumption contributes to sustainable marketing and consumer engagement by influencing green purchase intention and life satisfaction among Generation Z, while also assessing the moderating role of social influence. Grounded in Self-Determination Theory, a survey of 1541 Thai consumers aged 18–24 was analyzed using a structural equation model and path analysis to test the mediation framework. The results show that mindful consumption significantly enhances sustainability values and purchase intentions, with sustainability values mediating the relationship between mindful consumption and both behavioral and psychological outcomes. Moreover, social influence strengthens the impact of sustainable consumption on purchase intentions, highlighting the role of peers, networks, and societal norms in promoting ethical and environmentally responsible consumer behavior. The findings extend sustainable marketing theory by highlighting mindful consumption as a driver of both behavioral (green purchase intention) and psychological (life satisfaction) outcomes. Beyond its theoretical contribution, the study offers practical insights for businesses, educators, and policymakers on fostering value-driven relationships with young consumers through mindful and socially reinforced sustainability initiatives. Promoting mindful consumption and leveraging social influence provides a pathway to engage Generation Z in sustainability-oriented lifestyles, supporting long-term consumer loyalty and achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

1. Introduction

Sustainable marketing has become a critical approach for addressing the ecological and social challenges of today’s consumption-driven world. It emphasizes not only financial success but also ecological responsibility and social well-being, consistent with the triple bottom line framework [1]. To achieve these aims, businesses increasingly adopt holistic marketing—a comprehensive approach that integrates relationship, internal, integrated, and performance marketing across stakeholders including customers, employees, competitors, and society [2,3]. Such strategies highlight the importance of understanding consumer values and behaviors as the foundation for sustainable business practices.

Central to this sustainability discourse is the conceptualization of mindful consumption as “a consumer mindset of caring for self, for community, and for nature, that translates behaviorally into tempering the self-defeating excesses associated with acquisitive, repetitive and aspirational consumption” [4]. It is a value-driven approach in which individuals evaluate the environmental, social, and personal consequences of their purchasing decisions. Mindful consumption reflects care for self, community, and nature while practicing moderation in acquisitive and repetitive consumption [4,5,6]. This framework emphasizes conscious consideration of consumption’s impact on personal well-being, social equity, and environmental health. Building on this foundation, Gupta and Sheth [7] developed the first empirically validated scale for mindful consumption, identifying three core dimensions: awareness (conscious recognition of consumption impacts), caring (concern for effects on self, society, and environment), and temperance (moderation in consumption behaviors). Moreover, mindful advertising has been shown to encourage such behaviors [8], further reinforcing its relevance to sustainable marketing.

In an era increasingly defined by sustainability imperatives, Generation Z has emerged as a transformative consumer segment that fundamentally prioritizes authenticity, environmental consciousness, and ethical responsibility in their consumption decisions [9]. Generation Z places greater emphasis on sustainability signals, particularly in online environments, showing a stronger preference for sustainability labels and a higher likelihood of selecting sustainable options compared to Generation X, despite notable variation within the cohort [10]. Among Generation Z, eco-labels, user-generated content (UGC), and influencer endorsements significantly enhance green purchase intentions. Furthermore, environmental concern amplifies reliance on eco-labels and engagement with UGC, thereby establishing a reinforcing mechanism wherein heightened concern facilitates the processing of credible environmental signals and peer-to-peer diffusion [11]. In addition, members of Generation Z demonstrate awareness and appreciation of corporate environmental CSR initiatives; however, their evaluations differ according to gender and educational background, underscoring the necessity for differentiated and targeted CSR communication strategies [12]. In addition, the trustworthiness of eco-claims and labels remains crucial, as concerns about greenwashing can undermine purchase intentions, even among sustainability-minded youth [13]. Their behaviors increasingly signal a shift away from short-term gratification and materialism toward intentional, values-based living that aligns with sustainability. Research shows that mindful consumption is not only compatible with sustainable development, but also positively linked to life satisfaction and reduced materialism [14]. Therefore, Gen Z can be emphasized as a pivotal group for advancing sustainability through mindful consumption.

Despite growing scholarly interest in the relationship between mindful consumption and sustainability, the psychological mechanisms connecting mindfulness-based approaches to sustainable behavior remain insufficiently explored. To address this gap, the present study integrates Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to explain how mindful consumption enhances autonomous motivation and competence, ultimately leading to environmentally responsible actions and personal well-being. This study further examines the role of social influence, which remains especially critical in shaping consumer decisions within collectivist cultural contexts. By advancing understanding of these mechanisms, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how psychological and consumer behavior factors interact to shape sustainable lifestyles among Gen Z. It advances progress toward several of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Specifically, it supports SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) by encouraging more intentional and sustainability-oriented consumption habits, and SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) by linking mindful consumption to life satisfaction and personal well-being. Furthermore, the study aligns with SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) by offering insights into collaboration among businesses, educators, and policymakers to influence young consumers’ engagement in sustainability.

Over recent decades, Thailand has developed a unique sustainability framework called the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy (SEP), rooted in a Buddhist worldview that highlights the interconnectedness of the economy, society, and environment. This philosophy aligns closely with Buddhist mindfulness and has been incorporated into both policy and community practices [15]. Research grounded in SEP illustrates how mindful attitudes and behaviors can be nurtured and maintained at individual and collective levels, offering a culturally meaningful approach to mindful consumption [16]. Hence, this research study among Thai Generation Z subjects offer practical implications for designing interventions and sustainable marketing strategies that align with Gen Z values, thereby fostering long-term behavioral change.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Mindful Consumption and Young Consumers

Mindful consumption has emerged as a compelling concept in consumer behavior research, especially in the context of growing environmental and social concerns. Fischer et al. [5] highlight mechanisms such as disrupting habitual behaviors, aligning actions with personal values, and reducing materialistic tendencies, factors that are particularly meaningful for adolescents and young adults forming their identities in media-driven consumer environments, even though direct studies on mindful consumption in Gen Z remain limited [5]. Furthermore, empirical research has linked trait mindfulness to environmentally responsible behavior [17] and to health-related outcomes [18], with many studies focusing on student and young adult populations. These findings support the potential effectiveness of mindful consumption interventions targeted at youth [17,19].

Mindful consumption emphasizes self-awareness, intentionality, and values-based decision-making. It encourages consumers to question their habits, avoid overconsumption, and choose products that align with ethical, environmental, and social values. This behavior is closely linked to sustainability, as it supports reduced materialism, ethical production, and long-term responsibility [14]. Structural models based on university samples indicate that for Generation Z, consumer social responsibility and external motivators (both material and social) are significant predictors of sustainable behaviors, while collectivist values and perceived obstacles tend to have a lesser impact than commonly expected [20]. Furthermore, research suggests that mindful consumers are more likely to engage in sustainable behaviors and experience greater life satisfaction [6,21].

Among young consumers, however, there remains a notable gap between awareness and action. Gadhavi and Sahni [22] observed that despite awareness of fast fashion’s environmental impact, Gen Z consumers often struggle to align their values with actual purchase behavior. This highlights the need to better understand the psychological mechanisms that support mindful consumption in practice. Psychological factors such as temperance, intrinsic motivation, and self-regulation are central to fostering consistent, sustainability-oriented behavior.

Studies also show that mindfulness helps reduce materialistic tendencies [23] and enhances ethical purchasing, especially when combined with values such as environmental concern and perceived consumer effectiveness [5]. As such, mindful consumption serves as a promising driver of sustainable lifestyle choices among youth. Individuals practicing mindful consumption make purchase decisions that align with their values and beliefs, reflecting their focus on sustainability and ethical consumption [24]. This behavior translates into a higher intention to purchase green products, as mindful consumers prioritize environmentally friendly options as hypothesized that

- H1.

- Mindful consumption has a positive effect on green purchase intention.

2.2. Mindful Consumption and Sustainability

Mindful consumption plays a significant role in reinforcing sustainable consumption values. Individuals who practice mindfulness are more attuned to the long-term consequences of their actions and are thus more likely to value sustainability in their purchasing decisions [14,25]. These values serve as internal guides that shape environmentally responsible behavior, from green purchasing to ethical brand support.

For young consumers, sustainability values are increasingly viewed as an expression of personal identity and social consciousness. Quoquab and Mohammad [26] emphasized that mindful consumption helps individuals to reduce their material overconsumption and shift their attention toward quality of life and societal impact. Chatterjee et al. [27] further observed that mindful consumers weigh both internal motivations and contextual factors in their decision-making, fostering more consistent green behavior.

Mindful consumption can therefore bridge the “value–action gap” often observed among youth, where sustainable values are endorsed but not always enacted [28]. Individuals who practice mindful consumption are thus more inclined to internalize sustainable consumption values, reinforcing responsible and conscious consumer behavior; therefore, it is hypothesized that

- H2.

- Mindful consumption has a positive effect on sustainability consumption value.

2.3. Mindful Consumption and Individual Well-Being

Early evidence by Amel et al. [17] suggests that the “acting with awareness” facet of mindfulness predicts self-reported ecological behaviors, indicating that attention regulation facilitates sustainable habit formation. Geiger et al. [19] later identified an indirect link between mindfulness and ecological behavior via health practices such as nutrition and exercise, highlighting co-benefits for personal and planetary well-being. For Generation Z—who increasingly value sustainability, ethics, and authenticity—mindful consumption serves as a means of expressing identity and enhancing well-being through intentional, value-aligned choices [29].

Emerging research highlights that mindful consumption is positively associated with life satisfaction, particularly through its ability to reduce materialistic tendencies and enhance consumers’ sense of purpose [25]. Rather than seeking happiness through possessions, mindful consumers prioritize experiences, ethical values, and long-term impacts—an orientation that resonates strongly with young consumers who increasingly seek meaningful, value-driven lifestyles.

Mindfulness also strengthens the link between personal beliefs and actual behavior. By fostering deeper awareness of consumption consequences, it helps young individuals make choices that reflect their sustainability values [27,28]. This alignment leads to a stronger sense of control, ethical congruence, and fulfillment—key drivers of subjective well-being. Based on these findings, the following hypothesis is proposed:

- H3.

- Mindful consumption has a positive effect on life satisfaction.

2.4. Sustainability Consumption Value and Consumer Outcomes

Sustainability consumption values reflect the extent to which consumers prioritize ethical, environmental, and social responsibility in their purchase decisions. These values have become increasingly salient in shaping consumer behavior, influencing not only product preferences but also perceptions of brand authenticity and long-term loyalty. For firms, sustainability is thus positioned as more than an operational imperative; it serves as a strategic avenue to align with consumer values and foster meaningful connections with environmentally conscious segments. Among young consumers, these values increasingly form part of their identity and influence how they engage with brands. Gen Z consumers, in particular, are known for supporting companies that align with their ethical standards and environmental goals, making sustainability values a critical determinant of both attitudinal and behavioral outcomes [24,30].

Empirical studies suggest that sustainability consumption values positively influence green purchase intention. For example, Haws et al. [31] discovered that individuals with stronger green consumption values tend to prefer eco-friendly products, partly because they view the non-environmental features of these products more positively. Also, Mahmud et al. [24] found that mindful consumers with strong sustainability values were significantly more inclined to purchase environmentally friendly products. Similarly, Sreen et al. [23] highlighted that such values can mitigate materialistic tendencies, thereby enhancing pro-environmental attitudes—an insight particularly salient among Gen Z, who are often critical of excessive consumption and seek out brands with purpose-driven narratives. Therefore, consumers who endorse sustainability consumption values are more likely to make purchasing decisions that support environmental protection as hypothesized that

- H4.

- Sustainable consumption values have a positive effect on green purchase intention.

In addition to influencing behavior, sustainability consumption values are also associated with higher levels of life satisfaction. When young consumers act in accordance with their values, they are more likely to feel empowered, fulfilled, and aligned with their identity as responsible global citizens [29]. This value–behavior congruence supports intrinsic motivation and enhances psychological well-being, both of which are key priorities for younger consumers navigating complex global challenges.

By encouraging purchases that are not only ethical but also personally meaningful, sustainability values contribute to both consumer empowerment and overall life satisfaction. This connection highlights the broader role of sustainability in shaping holistic well-being, beyond the immediate consumption context. Therefore, it is hypothesized that

- H5.

- Sustainability consumption values have a positive effect on life satisfaction.

2.5. Conceptual Framework

In response to growing environmental concerns and shifting consumer values, mindful consumption has become a key theme in sustainable marketing and consumer behavior research. While recent studies have explored the links between mindful consumption and individual consumption habits, the broader interplay between mindful consumption, sustainability values, and psychological well-being remains underexplored, particularly among younger generations who are both highly value-driven and vulnerable to consumer pressures. This issue is especially salient in Thailand, where sustainability is guided by the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy (SEP), a national framework rooted in Buddhist principles emphasizing moderation, mindfulness, and balance [32]. These cultural foundations make Thailand a meaningful setting for examining how mindful consumption translates into sustainable consumption value and behavior.

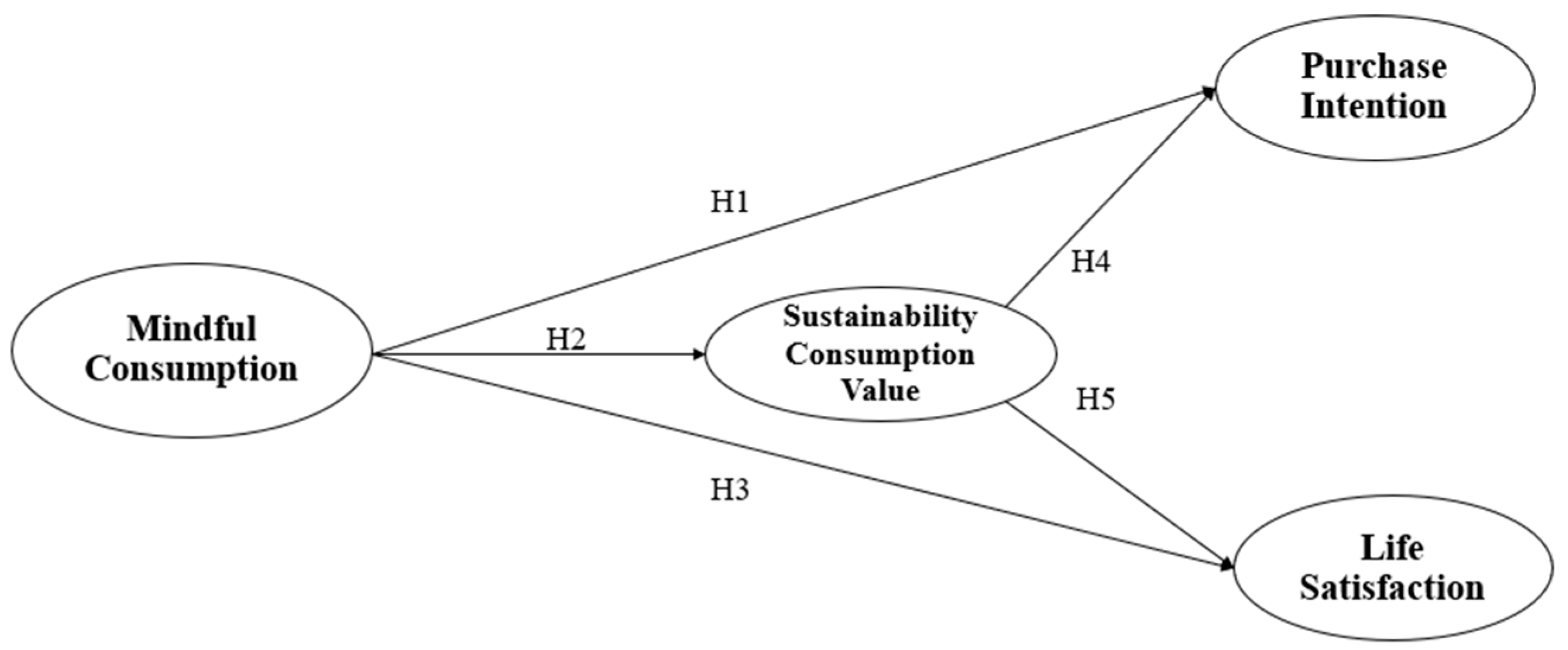

This study addresses this gap by proposing a comprehensive conceptual framework in Figure 1 that integrates psychological motivation with sustainable consumer behavior. Building on Self-Determination Theory, the model posits that mindful consumption enhances individuals’ intrinsic motivation to act in alignment with personal and environmental values. In doing so, it influences not only green purchase intention, but also life satisfaction, offering a more holistic perspective on how value-based behavior contributes to both individual and societal well-being.

Figure 1.

An effect of mindful consumption on sustainability consumption value model.

Although prior research has acknowledged the positive impact of mindfulness on environmental concern and ethical consumption [29], few studies have examined how these outcomes are jointly shaped by internalized sustainability values. The current framework introduces sustainability consumption value as a mediating mechanism that links mindful consumption with two critical outcomes: green purchase intention and life satisfaction.

3. Research Methodology

This study explores the attitudes, values, and behavioral intentions of young consumers aged 18–24 in relation to mindful consumption, sustainability values, and their psychological well-being. Generation Z has been identified as a key demographic with growing concerns about environmental and social issues, making them a pivotal group in driving the shift toward sustainable consumption [33]. Understanding how this cohort engages with mindful consumption offers critical insights into their role in shaping a more sustainable future.

A quantitative research approach was employed to examine the proposed conceptual framework and test the hypothesized relationships among key constructs. Data were collected using an online structured questionnaire by Google Form, distributed through convenience sampling. Before proceeding, participants were informed of the study’s objectives, ethical considerations, and their right to withdraw at any time. Their willingness to voluntarily participate was obtained prior to completing the survey. The screening section included questions assessing respondents’ interest in sustainability-related topics and confirming that they were within the target age range of 18–24 years. The survey targeted Generation Z consumers in Thailand, primarily from Bangkok and its vicinities, the nation’s largest urban and economic center, where young consumers are most exposed to sustainability campaigns, digital platforms, and modern consumption. While convenience sampling limits generalizability, it is considered acceptable for theory testing and model validation [34]. Participants were also informed by the research team that the study results would be shared after publication to help enhance understanding of sustainable consumption among young Thai consumers. A sample of 400 is generally sufficient for large populations with a 5% margin of error [35]. This study significantly exceeded that threshold, obtaining 1541 valid responses after removing pattern answers, unrealistically short completion times, incomplete, and outlier cases, thereby strengthening statistical power and confidence in the findings.

Questionnaire Design and Measurement

The structured questionnaires were developed based on the items from previous research. The surveys include 4 sections. (1) A research introduction with objectives and ethical details; (2) general questions and demographic profiles, such as participants’ age, gender, educational background, and other relevant profiles that may influence mindful consumption patterns; (3) attitude and belief questions (mindful consumption, sustainability consumption value, life satisfaction); and (4) respondents’ perception and behavior related to sustainable consumption. Respondents were asked to provide their opinions in 5-point Likert scale.

To assess mindful consumption, this study adapted the measurement scale originally developed by Gupta and Verma [36]. The original instrument consisted of 15 items across three dimensions: Acquisitive Temperance, Repetitive Temperance, and Aspirational Temperance. However, following model refinement and confirmatory analysis, several items were excluded to enhance the scale’s construct validity. In particular, the Repetitive Temperance dimension was removed, possibly due to conceptual overlap with the other dimensions or limited contextual relevance to the current sample. Cultural differences may have also influenced the interpretability and effectiveness of certain items, underscoring the importance of cultural adaptation in scale validation. Ultimately, the final version retained seven items across two dimensions—Acquisitive Temperance and Aspirational Temperance (Appendix A Table A1). Sample items include the following: “I prefer to buy reusable products over disposable products”, “Sharing a product or service is better than owning it for individual use”, and “I try to reuse a product in some way”.

Sustainability consumption values were measured using six items from the GREEN scale developed by Haws et al. [31], which has been widely applied in the context of eco-conscious consumer behavior. This scale captures the extent to which consumers value environmental sustainability in their consumption choices. For green purchase intention, the scale was measured using five items adapted from Sun and Wang [37], focusing on consumers’ intentions to engage in environmentally friendly decision-making. Example items include the following: “I intend to purchase green products in the future,” and “I plan to purchase green products because of their positive environmental contribution.” While Life satisfaction was evaluated using Diener et al.’s Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) [38], a well-established five-item scale that assesses respondents’ overall satisfaction with their lives. Items such as “I am satisfied with my life” and “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal” were included.

To measure social influence, four items were adapted from the scale developed by Chen et al. [39], which examines the role of perceived social expectations and peer-driven norms in shaping environmentally responsible consumption. This construct captures how young consumers’ purchase decisions are influenced by the opinions, behaviors, and perceived judgments of others in their social environment. Sample statements include the following: “Purchasing green products enhances the impression others have of me”, “Buying environmentally friendly products helps me gain approval from those around me”.

To ensure clarity and face validity, the questionnaire was translated and pilot-tested with 40 participants within the target demographic. Feedback from this pretest was used to refine the language and layout of the final survey instrument. The reliability and validity of the measurement scales were assessed through Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (C.R.), and average variance extracted (AVE). Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the adequacy of the measurement model, followed by covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) using AMOS 18 to test the hypothesized relationships, as this method is suitable for theory validation with large samples. All latent variables were modeled as reflective constructs, consistent with prior consumer behavior and sustainability research, where indicators are manifestations of underlying theoretical concepts. Model fit was evaluated with standard CB-SEM indices, including χ2, GFI, CFI, NFI, and RMSEA. In addition, Hayes’ PROCESS Macro [40] was employed to perform path analysis and test mediation and moderation effects, particularly the moderating role of social influence on the relationship between sustainability values and green purchase intention.

4. Results and Findings

Descriptive statistics presented in Table 1 provide an initial overview of the sample characteristics. The respondent pool is predominantly female, accounting for 67.62% of the total, while males represent 32.38%. As the study focuses on understanding the attitudes and behaviors of younger generations, the age distribution is between 18 and 24 years old. In terms of educational attainment, a substantial majority (79.62%) hold a bachelor’s degree, suggesting that the sample is relatively well-educated. Income distribution data indicate that 51.20% of participants earn between 10,000 and 30,000 Baht per month, while 42.38% earn less than 10,000 Baht. These figures suggest that a significant portion of the sample represents lower-income groups, providing a valuable perspective on how income may intersect with sustainable consumption behaviors among young Thai consumers. While there may be concerns regarding the external validity of using student samples [41], students are a highly relevant and engaged group, especially in sustainability research. Their strong awareness of environmental issues makes them an ideal sample for examining the psychological and behavioral factors that influence sustainable consumption. Using students also helps control for age and education level, reducing variability in responses [42].

Table 1.

Respondents’ characteristics.

4.1. Measurement Reliabilities and Validities

The reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha or composite reliability) for all constructs are reported to be above 0.80 (Table 2), which is considered acceptable according to Nunnally [35]. This suggests that the measurement items within each construct are internally consistent. To provide a clearer overview of the measurement quality, all scale items, and psychometric properties, the results in Table 3 present the summary of C.R. and AVE for each construct and factor loading (in Appendix A Table A1). All constructs demonstrate convergent validity with AVE values above 0.5, except for mindful consumption, which slightly fell below this threshold. However, as AVE is a conservative criterion, convergent validity remains acceptable given the high C.R. value (0.81 > 0.7), consistent with Malhotra [43].

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation, correlations, Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity, C.R. and AVE.

Discriminant validity was verified using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, where the square roots of AVE (bold diagonals in Table 3) exceeded inter-construct correlations. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) further confirmed the adequacy of the measurement model (χ2(224) = 1087.43, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.94; CFI = 0.96; NFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.05 [90% CI: 0.045–0.051]), indicating a good model fit.

4.2. SEM Results and Hypothesis Testing

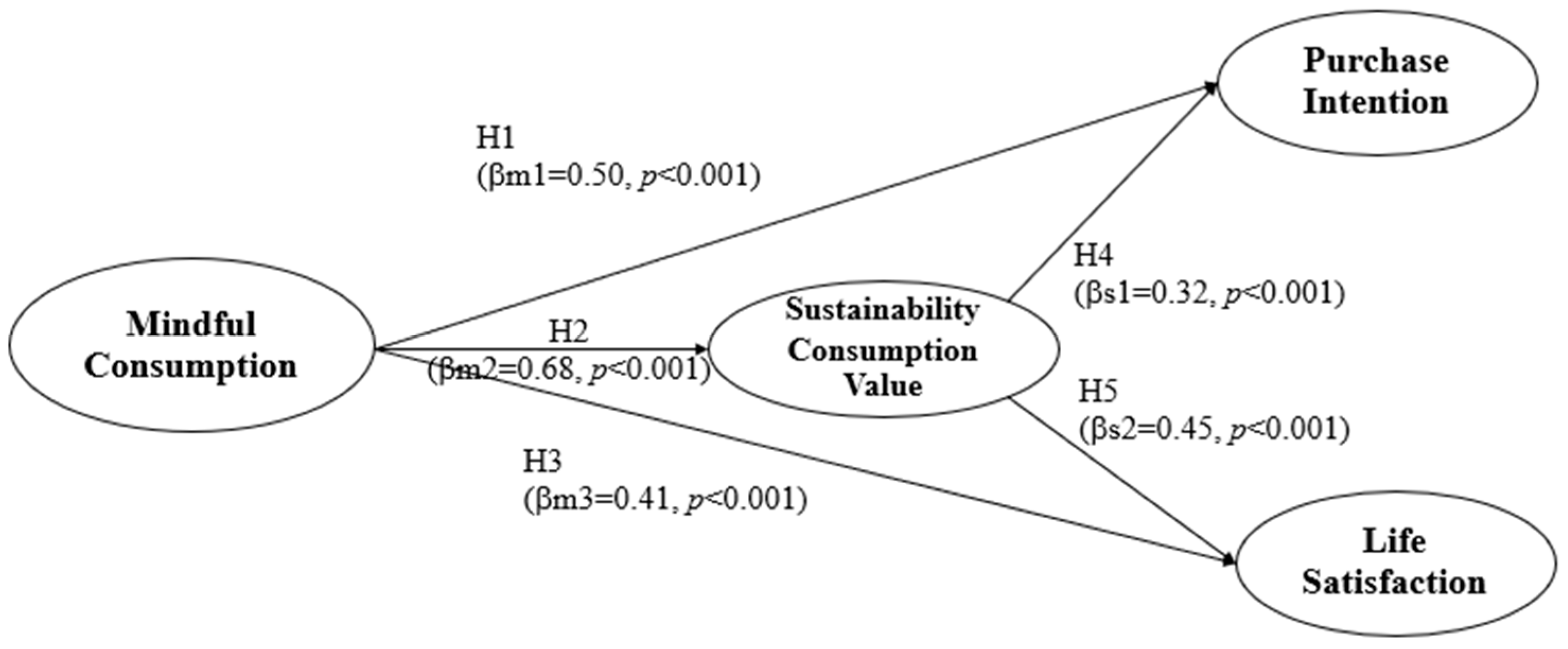

Following the validation of the measurement model, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to test the proposed hypotheses using path analysis. The results, which are summarized in Table 4, confirm the hypothesized relationships among the variables, aligning with the theoretical framework and prior empirical research. Among the tested paths, the strongest relationship was observed between the mindful consumption and sustainability consumption values (β = 0.68, p < 0.001), indicating that individuals who engage in mindful consumption are significantly more likely to adopt sustainability-oriented consumption behaviors.

Table 4.

Hypotheses evaluation.

Regarding green purchase intention, the model explained 57% of its variance (R2 = 0.57), suggesting a substantial influence of the predictors. Both mindful consumption (β = 0.50, p < 0.001) and sustainability consumption value (β = 0.32, p < 0.001) were found to have a positive and significant effect on purchase intention. Notably, the effect of mindful consumption was stronger, underscoring its central role in shaping environmentally conscious purchase behavior.

For life satisfaction, the model explained 63% of the variance (R2 = 0.63). Both mindful consumption (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and sustainability consumption value (β = 0.45, p < 0.001) exhibited significant positive effects. These findings highlight that engaging in mindful and sustainable consumption practices contributes meaningfully to an individual’s overall sense of life satisfaction. Collectively, the results support all hypothesized relationships and underscore the dual influence of psychological mindfulness and sustainability values on both behavioral and psychological outcomes among young consumers, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Results from the conceptual framework.

4.3. Mediating Role of Sustainability Consumption Value and Moderating Effects of Social Influence

To further explore the underlying mechanisms in the conceptual model, mediation and moderation analyses were conducted using Hayes’ PROCESS Macro (Model 7) as recommended for path-based conditional process modeling [40]. The results in Table 5 indicate that sustainable consumption value significantly mediates the relationship between mindful consumption and both green purchase intention and life satisfaction.

Table 5.

Additional analysis for mediation and moderation.

For green purchase intention, the indirect effect of mindful consumption through sustainable consumption value (MC → SCV → PI) was statistically significant and positive (β = 0.356, SE = 0.021, 95% CI [0.315, 0.398]). This suggests that a considerable portion of the effect of mindfulness on purchase intention is explained by its influence on sustainability-related values. Similarly, in the life satisfaction model (MC → SCV → LS), the standardized indirect effect was also significant (β = 0.113, SE = 0.027, 95% CI [0.079, 0.149]), though the magnitude of the effect was smaller than that observed for purchase intention. These results confirm that sustainable consumption value serves as a meaningful mediator, with a stronger mediating influence on behavioral outcomes (purchase intention) than on psychological outcomes (life satisfaction).

To validate these findings, a mediation model was further tested using covariance-based SEM with bootstrapping in AMOS. Results were consistent with the PROCESS analysis, confirming that sustainability consumption value significantly mediates the relationship between mindful consumption and both purchase intention (β = 0.22, 95% CI [0.18, 0.26]) and life satisfaction (β = 0.31, 95% CI [0.27, 0.35]). The total effects of mindful consumption on these outcomes were strong (β = 0.72 for both), reinforcing the robustness of the mediation and the convergent validity across analytical approaches.

In terms of moderation effect (Table 5), the interaction between sustainable consumption and social influence (β = 0.055, p < 0.01) shows a positive relationship, suggesting that higher social influence strengthens the effect of sustainable consumption on purchase intention. This implies that sustainable consumption becomes more influential under high social influence. However, the indirect impact of mindful consumption on purchase intention through sustainable consumption increases with social influence; the moderated mediation effect is not statistically significant.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study offer important insights into the behavioral patterns of young consumers in relation to mindful consumption and sustainability. The strong positive association between mindful consumption and sustainability values suggests that cultivating mindful consumption may enhance environmental awareness and foster long-term commitments to sustainable lifestyles. Among young consumers—who are often at the forefront of value-driven purchasing—this connection indicates that promoting mindful habits could be a viable path to shaping environmentally responsible behavior. These results align with previous research emphasizing the overlap between mindfulness and sustainable behaviors [5], reinforcing the idea that awareness, intentionality, and ethical concern are deeply interrelated in the consumer decision-making process of this generation.

Importantly, mindful consumption demonstrated a stronger effect on green purchase intention (β = 0.50, p < 0.001) than sustainability values alone (β = 0.32, p < 0.001). This highlights that intrinsic awareness and intentional decision-making are more immediate drivers of behavior than abstract sustainability appeals. For sustainable marketing, this finding highlights the importance of campaigns that prioritize mindful engagement and authentic consumer experiences, rather than relying solely on traditional sustainability messaging.

Life satisfaction was also significantly influenced by both mindful consumption (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and sustainable consumption values (β = 0.45, p < 0.001), with the model explaining 63% of the variance. These results suggest a dual benefit: mindful and sustainable practices not only support pro-environmental outcomes, but also contribute to personal well-being. This reinforces the idea that sustainability can be marketed as both a collective responsibility and an avenue for enhancing individual quality of life. This dual pathway is consistent with previous findings by Dhandra [25] and Manchanda et al. [44]; it offers a hopeful narrative for young consumers seeking meaningful, values-based lifestyles.

Mediation and moderation analyses revealed that sustainable consumption values serve as a key pathway between mindfulness and outcomes, while social influence strengthens the link between sustainable consumption values and purchase intentions. These findings emphasize that young consumers’ sustainable behaviors are shaped by the interplay of personal awareness, value alignment, and peer influence. In the context of sustainable marketing, strategies that connect mindful consumption with socially reinforced norms can generate deeper engagement and encourage long-term pro-environmental consumer choices.

These findings are particularly significant within the Thai cultural context, where Buddhist principles and the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy have long emphasized mindfulness, moderation, and prudent consumption as pathways to resilience and well-being [15]. Such cultural and policy foundations may have strengthened the observed links between mindful consumption, sustainability values, and life satisfaction. While these influences may limit direct generalization to other contexts, they offer valuable insights for societies with similar cultural or developmental orientations seeking to promote sustainable consumption through value-based and culturally grounded approaches.

Additionally, this study’s sample was drawn primarily from Bangkok and nearby urban areas, capturing the behaviors of a single generational cohort within a distinct cultural context. As Thailand’s capital and economic hub, Bangkok exposes young consumers to sustainability campaigns, digital platforms, and peer influence, which may intensify mindful and sustainable practices. While these findings are valuable, they remain context-specific and should not be generalized to other cultural or demographic settings. Future research should incorporate cultural frameworks and cross-cultural comparisons to examine how varying social norms, traditions, and value orientations shape the relationships between mindful consumption, sustainability values, and well-being.

6. Theoretical Contribution and Managerial Implication

This study makes substantial contributions to the theoretical and practical understanding of mindful consumption, particularly in the context of younger consumers. By integrating self-determination theory, the research offers a comprehensive framework that explains how mindful consumption fosters both sustainable consumer behavior and individual well-being. This integrated perspective builds upon the previous literature [25,45] to provide a more holistic understanding of the psychological underpinnings of sustainable consumption.

Theoretically, the study advances the literature in four key ways. First, it highlights the dual role of mindful consumption in reducing materialistic tendencies while enhancing environmental awareness—both of which are central to responsible consumption. The positive mediating effect of sustainability values strengthens our understanding of the cognitive and emotional pathways that link mindfulness to behavioral outcomes, such as green purchase intention, and psychological outcomes, such as life satisfaction. Second, the research confirms that mindful consumption cultivates a stronger sense of purpose and competence, which are key drivers of intrinsic motivation as outlined in self-determination theory. This suggests that consumers who align their purchasing decisions with their personal and environmental values are more likely to experience long-term satisfaction and engage in pro-environmental behaviors. Third, the study introduces social influence as a crucial boundary condition, demonstrating that sustainable consumption has a stronger effect on purchase intention when consumers perceive higher levels of social pressure. This finding highlights the socially embedded nature of sustainable behaviors, where peers, social networks, and cultural norms amplify the impact of individual mindfulness on environmentally conscious choices. Finally, by focusing on young consumers, the study contributes to generational research in consumer psychology, showing that mindful consumption has unique salience among youth who increasingly prioritize sustainability, ethics, and purpose in their purchase decisions. These contributions broaden the theoretical discourse on how mindful and sustainable consumption interact with social influence to drive behavioral and psychological outcomes in sustainability contexts.

Building on Sheth et al. [4], marketers can foster mindful consumption by reinterpreting the four Ps—product, price, promotion, and place—through strategies such as designing durable and repairable products, internalizing environmental and social costs in pricing, using educational campaigns to encourage sustainable lifestyles, and enabling reuse and sharing. The holistic marketing framework [2] further emphasizes the alignment of internal operations with external stakeholder relationships, thereby embedding sustainability across the entire value chain. While this study does not isolate specific product categories, the findings highlight the importance of eco-friendly materials, ethical production, and innovative solutions that make sustainability both competitive and aspirational in youth markets.

At the consumer level, the results suggest that mindful and sustainability-oriented young consumers, particularly Generation Z, favor brands that communicate openly about their practices [46]. Transparency in sourcing, production, and environmental performance should therefore be regarded as a strategic lever for building trust and long-term loyalty, especially given Gen Z’s tendency to align brand narratives with personal values on social media [47]. Marketing strategies that frame sustainable behavior as socially endorsed—through influencers, community engagement, or peer networks—can further amplify green behaviors, particularly among consumers sensitive to social influence. Beyond offering eco-friendly products, brands must appeal to autonomy, authenticity, and purpose, thereby enhancing consumer well-being while positioning sustainability as both a competitive advantage and a societal good.

Moreover, this study highlights the strategic role of educational outreach and culturally grounded values in advancing sustainable marketing and customer management. Businesses can collaborate with educational institutions to embed mindful consumption principles into curricula, while simultaneously using brand-led initiatives to engage young consumers in reflecting on how their choices affect personal well-being, society, and the environment. In Thailand, Buddhist teachings—emphasizing modesty, non-attachment, and ethical livelihood—offer a culturally resonant foundation for strengthening sustainable consumption habits. For managers, incorporating such values into sustainability campaigns not only reinforces authenticity but also deepens emotional connections with consumers, fostering long-term loyalty and trust. By aligning marketing strategies with both global goals and local cultural wisdom, firms can position themselves as credible sustainability leaders while encouraging customers to internalize mindful habits. These efforts advance SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals), demonstrating how cross-sector and culturally responsive approaches can simultaneously strengthen consumer relationships and contribute to sustainable development.

7. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study provides valuable insights into mindful consumption among young Thai consumers; however, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the scope is restricted to Generation Z in Thailand, who were the group addressed and surveyed. While Gen Z are highly relevant to sustainability research due to their strong environmental awareness, the findings may not be generalizable to older generations whose values, resources, and consumption patterns differ. Second, the respondents, being relatively young with lower income and limited education levels, may not fully represent broader populations. As a result, the perceptions and behaviors captured in this study may not be applicable to other age groups, income levels, or educational backgrounds. Third, this study examines mindful consumption within the context of general consumption, which remains somewhat vague and could benefit from more specificity. The absence of a clear definition of general consumption leads to ambiguity regarding which particular behaviors are being examined. Given that mindful consumption can manifest differently across various product categories (e.g., clothing, electronics), it would be valuable to explore how specific consumption contexts—such as green consumption—may influence consumer behavior. Finally, as a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study, the findings are limited to associations rather than causality, and self-reported responses may be subject to bias. The use of convenience sampling also constrains the representativeness.

Future research should address current limitations by refining the measurement of mindful consumption across diverse populations, particularly within various Asian contexts, to better understand how cultural and socioeconomic factors influence these practices. Expanding the demographic scope would offer more generalizable insights into how young consumers engage with sustainability. Additionally, future studies should empirically examine the specific sustainability outcomes of mindful consumption—environmental, social, and economic—and identify which dimensions, such as carbon footprint reduction or ethical labor support, are most directly impacted. Further exploration into distinct behavioral domains of mindful consumption—such as mindful buying, eating, and traveling—is also recommended, as these may yield differing effects on consumer decision-making and brand perception due to varying emotional and psychological drivers [48]. Understanding these nuances can offer more targeted guidance for sustainable marketing strategies and sustainability initiatives, highlighting how different types of mindful behavior contribute to broader sustainable consumption.

8. Conclusions

This study highlights mindful consumption as a strategic lever for sustainable and holistic marketing, demonstrating its impact on green purchase intentions and life satisfaction among young consumers. Grounded in Self-Determination Theory, the findings show that mindful consumption fosters intrinsic motivation, leading to value-aligned behaviors that strengthen both individual well-being and societal sustainability. Mindful consumption exerts a stronger influence on purchase intention than sustainability values alone, with sustainability values mediating this effect and social influence reinforcing it.

From a managerial perspective, embedding mindful consumption into holistic marketing strategies allows brands to integrate social, environmental, and consumer dimensions into a unified approach. Sustainable marketing that links consumer well-being with brand purpose can enhance authenticity, trust, and loyalty—ensuring enduring customer relationships. By leveraging social influence and education within sustainability campaigns, firms can normalize responsible consumption while positioning themselves as sustainable brands. These efforts align with SDG 12 and SDG 17 and support long-term consumer engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.S. and S.S.; methodology, S.L.S.; software, S.L.S.; validation, S.L.S.; formal analysis, S.L.S.; investigation, S.L.S. and S.S.; resources, T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.S., S.S. and T.D.; writing—review and editing, S.L.S. and T.D.; visualization, S.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee for Human Research of Bangkok University (protocol code 416702032 and 5 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement items and factor loadings.

Table A1.

Measurement items and factor loadings.

| Construct | Item Code | Questionnaire Item (5-Point Likert Scale) | Standardized Loading (β) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mindful consumption (MC) | MC2 | I avoid buying more products than I need to reduce clutter at home. | 0.58 |

| MC4 | I prefer to buy reusable products over disposable ones. | 0.65 | |

| MC9 | I prefer sharing products/services rather than owning them solely for myself. | 0.58 | |

| MC10 | Sharing a product is better than owning it for individual use. | 0.65 | |

| MC12 | Sharing has more social value than individual ownership. | 0.57 | |

| MC13 | I try to reuse a product in some way before discarding it. | 0.68 | |

| MC14 | If a product is no longer useful to me, I pass it on to others instead of throwing it away. | 0.57 | |

| Sustainability consumption value (SCV) | SC1 | It is important to me that the products I use do not harm the environment. | 0.79 |

| SC2 | I consider the potential environmental impact of my actions when making many of my decisions. | 0.82 | |

| SC3 | My consumption behavior is often influenced by my environmental concerns. | 0.79 | |

| SC4 | I am concerned about wasting the resources of our planet. | 0.7 | |

| SC5 | I would describe myself as environmentally responsible. | 0.83 | |

| SC6 | I am willing to make sacrifices to protect the environment. | 0.81 | |

| Purchase intention (PI) | PI1 | I intend to purchase environmentally friendly products in the future. | 0.89 |

| PI2 | I will consider switching to environmentally friendly products. | 0.8 | |

| PI3 | I plan to purchase environmentally friendly products. | 0.86 | |

| PI4 | I prefer to buy environmentally friendly products over conventional products. | 0.83 | |

| PI5 | I will make an effort to buy environmentally friendly products. | 0.85 | |

| Life satisfaction (LS) | LS1 | In most ways my life is close to my ideal. | 0.85 |

| LS2 | The conditions of my life are excellent. | 0.9 | |

| LS3 | I am satisfied with my life. | 0.84 | |

| LS4 | So far I have gotten the important things I want in life. | 0.88 | |

| LS5 | If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. | 0.85 |

Table A2.

Bootstrapping results for mediation effects from SEM.

Table A2.

Bootstrapping results for mediation effects from SEM.

| Bootstrapping 95% (CI) | |||||

| Indirect Effect | Coefficient | Standard Error | Lower | Upper | Conclusion |

| MC ⟶ SCV ⟶ PI | 0.220 *** | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.26 | Mediation |

| MC ⟶ SCV ⟶ LS | 0.310 *** | 0.021 | 0.27 | 0.35 | Mediation |

| Total Effect | |||||

| MC ⟶ PI | 0.720 *** | 0.03 | 0.66 | 0.78 | |

| MC ⟶ LS | 0.720 *** | 0.03 | 0.66 | 0.78 | |

Note: bootstrap based on 5000 samples, bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. MC= mindful consumption, SCV = sustainability consumption value; PI = purchase intention; LS = life satisfaction. *** p < 0.001.

References

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada; Stony Creek, CT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L.; Kotler, P. Holistic marketing: A broad, integrated perspective to marketing management. In Does Marketing Need Reform? Fresh Perspectives on the Future; Sheth, J.N., Sisodia, R.S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 300–305. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L.; Chernev, A. Marketing Management; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2021; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.; Sethia, N.; Srinivas, S. Mindful Consumption: A Customer-Centric Approach to Sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Stanszus, L.; Geiger, S.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness and Sustainable Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review of Research Approaches and Findings. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Milne, G.R.; Ross, S.M.; Mick, D.G.; Grier, S.A.; Chugani, S.K.; Chan, S.S.; Gould, S.; Cho, Y.-N.; Dorsey, J.D.; et al. Mindfulness: Its Transformative Potential for Consumer, Societal, and Environmental Well-Being. J. Public Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sheth, J. Mindful consumption: Its conception, measurement, and implications. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2024, 52, 1531–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikalgar, A.; Menon, P.; Mahajan, V. Towards customer-centric sustainability: How mindful advertising influences mindful consumption behaviour. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2024, 16, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halibas, A.; Akram, U.; Hoang, A.-P.; Thi Hoang, M.D. Unveiling the future of responsible, sustainable, and ethical consumption: A bibliometric study on Gen Z and young consumers. Young Consum. 2025, 26, 142–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, B.M.; Rausch, T.M.; Brandel, J. The Importance of Sustainability Aspects When Purchasing Online: Comparing Generation X and Generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopoulos, A.; Poulis, A.; Theodoridis, P.; Kalampakas, A. Influencing Green Purchase Intention through Eco Labels and User-Generated Content. Sustainability 2023, 15, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, J.; Marcinkowska, E. Environmental CSR and the Purchase Declarations of Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margariti, K.; Hatzithomas, L.; Boutsouki, C. Elucidating the Gap between Green Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior through the Prism of Greenwashing Concerns. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, T.; Kjønstad, B.G.; Barstad, A. Mindfulness and sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 104, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-C. Sufficiency economy philosophy: Buddhism-based sustainability framework in Thailand. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2995–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsakornrungsilp, P.; Pongsakornrungsilp, S. Mindful tourism: Nothing left behind–creating a circular economy society for the tourism industry of Krabi, Thailand. J. Tour. Futures 2021, 9, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel, E.; Manning, C.; Scott, B. Mindfulness and Sustainable Behavior: Pondering Attention and Awareness as Means for Increasing Green Behavior. Ecopsychology 2009, 1, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, T.; Stanszus, L.S.; Geiger, S.M.; Fischer, D.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness Training at School: A Way to Engage Adolescents with Sustainable Consumption? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Otto, S.; Schrader, U. Mindfully Green and Healthy: An Indirect Path from Mindfulness to Ecological Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.; Min, M. Gen Z consumers’ sustainable consumption behaviors: Influencers and moderators. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 25, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Prabha, V.; Kumar, V.; Saxena, S. Mindfulness in marketing & consumption: A review & research agenda. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 74, 977–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhavi, P.; Sahni, H. Analyzing the Mindfulness of young Indian consumers in their fashion consumption. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Understanding the relationship between different facets of materialism and attitude toward green products. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, S.; Mohamed Anuar, M.; Masa Halim, M.H.; Halim, A.; Yaakop, A. The Influence of Self Care on Mindful Consumption Behaviour. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 5, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandra, T.K. Achieving triple dividend through mindfulness: More sustainable consumption, less unsustainable consumption and more life satisfaction. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 161, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. A review of sustainable consumption (2000 to 2020): What we know and what we need to know. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Sreen, N.; Sadarangani, P.H.; Gogoi, B.J. Impact of green consumption value and context-specific reasons on green purchase intentions: A behavioral reasoning theory perspective. J. Glob. Mark. 2022, 35, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essiz, O.; Yurteri, S.; Mandrik, C.; Senyuz, A. Exploring the value-action gap in green consumption: Roles of risk aversion, subjective knowledge, and gender differences. J. Glob. Mark. 2023, 36, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Consumers’ Sustainable Purchase Behaviour: Modeling the Impact of Psychological Factors. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufer, B.; Grabner-Kräuter, S. How consumer networks contribute to sustainable mindful consumption and well-being. J. Consum. Aff. 2023, 57, 757–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.; Winterich, K.; Naylor, R. Seeing the World through GREEN-tinted Glasses: Green Consumption Values and Responses to Environmentally Friendly Products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2013, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Thailand Human Development Report 2007: Sufficiency Economy and Human Development; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): Bangkok, Thailand, 2007; pp. 1–130. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, G.; Pathak, P. Intention to buy eco-friendly packaged products among young consumers of India: A study on developing nation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, N. Description and explanation of pragmatic development: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research. System 2018, 75, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill Companies, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Verma, H. Mindfulness, mindful consumption, and life satisfaction: An experiment with higher education students. J. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 12, 456–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S. Understanding consumers’ intentions to purchase green products in the social media marketing context. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 860–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Horowitz, J.; Emmons, R.A. Happiness of the very wealthy. Soc. Indic. Res. 1985, 16, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J.; Tsai, P.-H.; Tang, J.-W. How informational-based readiness and social influence affect usage intentions of self-service stores through different routes: An elaboration likelihood model perspective. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2022, 28, 380–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, R.; Merunka, D. The use and misuse of student samples: An empirical investigation of European marketing research. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Reynolds, N.L.; Simintiras, A.C. The impact of response styles on the stability of cross-national comparisons. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Manchanda, P.; Arora, N.; Nazir, O.; Islam, J.U. Cultivating sustainability consciousness through mindfulness: An application of theory of mindful-consumption. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonti, E.; Rigopoulos, G. An empirical exploration on mindfulness and mindful consumption. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Technol. 2022, 6, 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lubowiecki-Vikuk, A.; Dąbrowska, A.; Machnik, A. Responsible consumer and lifestyle: Sustainability insights. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprawan, L.; Oentoro, W.; Suttharattanagul, S.L. A test of moderated serial mediation model of compulsive buying among Gen Z fandoms moderated by trash talking. Young Consum. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Moschis, G.P. Antecedents and outcome of mindful buying. J. Consum. Aff. 2023, 57, 1684–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).