The Dynamic Interplay of Renewable Energy Investment: Unpacking the Spillover Effects on Renewable Energy Tokens, Fossil Fuel, and Clean Energy Stocks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Importance and Future of Renewable Energy

2.2. Digital Tokens and Renewable Energy

2.3. Interconnectedness of Asset Classes

2.4. Impact of Green Finance

2.5. Cryptocurrencies and Energy Markets

2.6. Emerging Assets and Portfolio Management

3. Data and Methodology

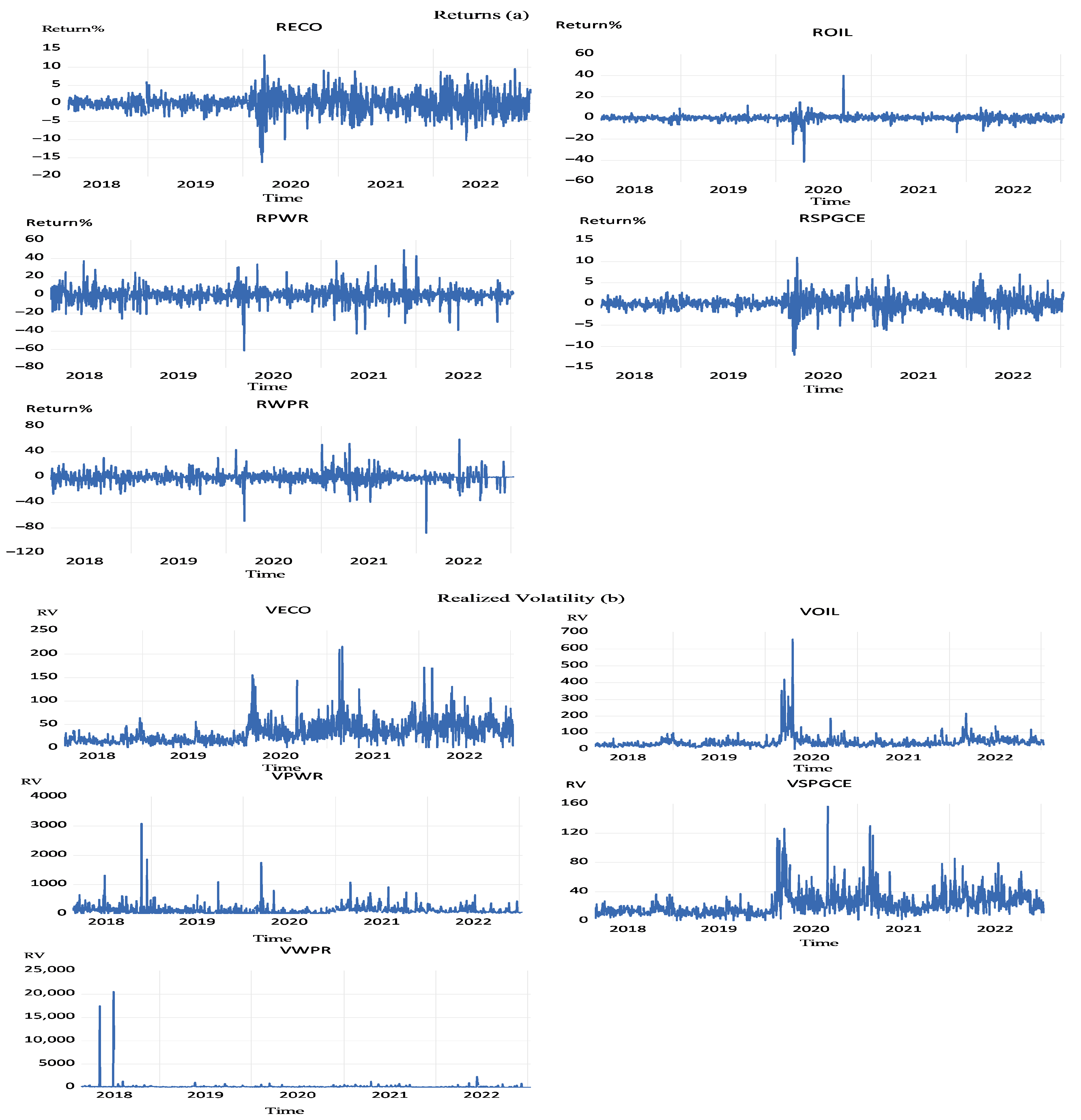

3.1. Data

3.2. TVP-VAR Methodology

3.3. QVAR Methodology

3.4. Model Parameters and Stability Checks

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Averaged Dynamic Connectedness

4.2. Average Dynamic Connectedness for Realized Volatility

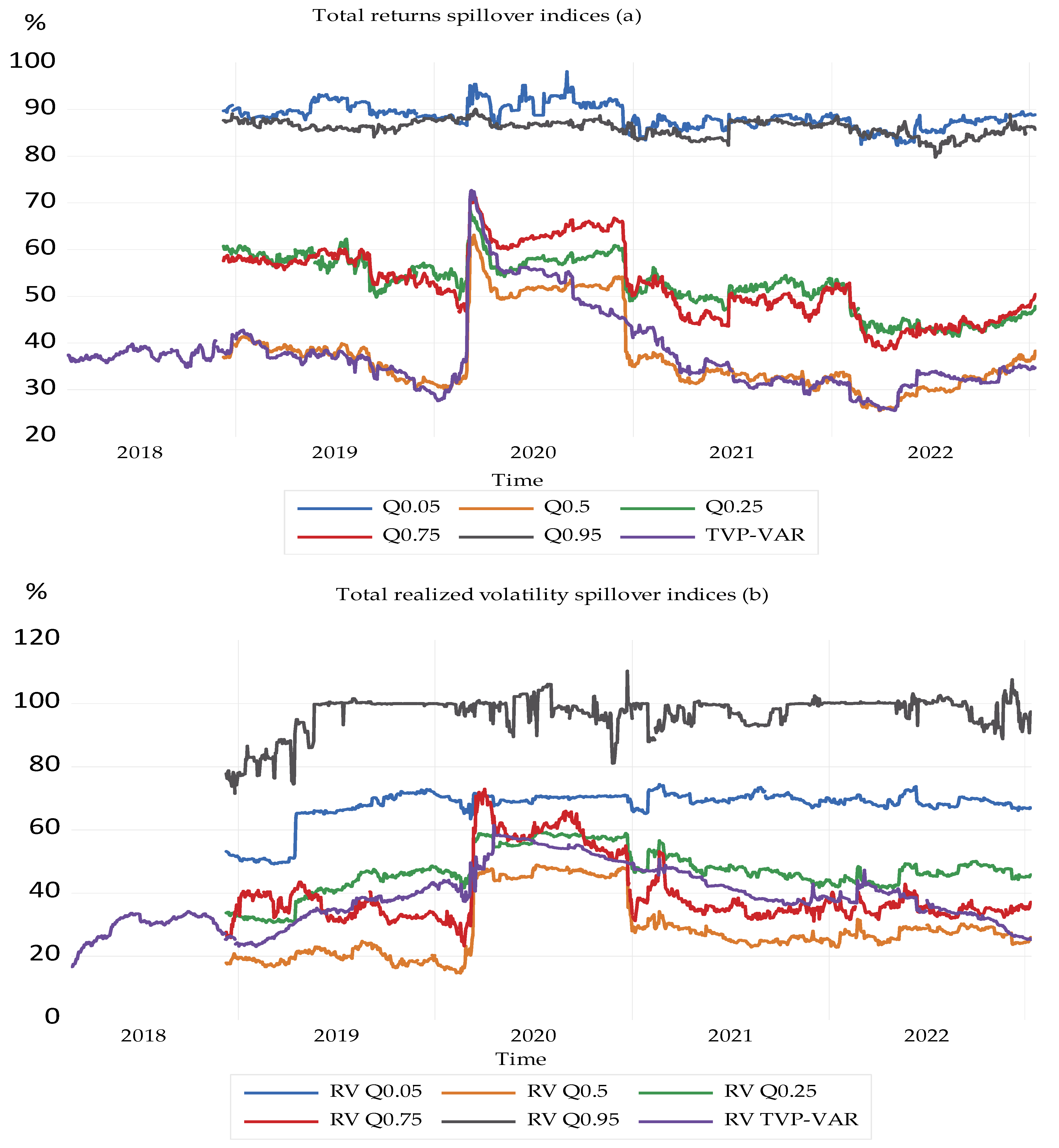

4.3. Dynamic Total Connectedness

4.4. Net Pairwise Directional Connectedness

4.5. Connectivity Dynamics Plot

4.6. Reliability of TVP-VAR Through TCI Analysis Across COVID-19 Periods

4.7. Comparative Analysis of Total Spillover Effects: QVAR vs. TVP-VAR

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

References

- Holechek, J.L.; Geli, H.M.E.; Sawalhah, M.N.; Valdez, R. A global assessment: Can renewable energy replace fossil fuels by 2050? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abakah, E.J.A.; Chowdhury, M.A.F.; Abdullah, M.; Hammoudeh, S. Energy tokens and green energy markets under crisis periods: A quantile downside tail risk dependence analysis. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, O. Fuel Cell and Hydrogen-based Hybrid Energy Conversion Technologies. In Prospects of Hydrogen Fueled Power Generation; River Publishers: Aalborg, Denmark, 2024; pp. 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Date, A.; Shabani, B. Towards self-water-sufficient renewable hydrogen power supply systems by utilising electrolyser and fuel cell waste heat. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 137, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C. Digitalization and decentralization driving transactive energy Internet: Key technologies and infrastructures. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 126, 106593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorri, A.; Luo, F.; Kanhere, S.S.; Jurdak, R.; Dong, Z.Y. SPB: A secure private blockchain-based solution for distributed energy trading. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2019, 57, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongthongtham, P.; Marrable, D.; Abu-Salih, B.; Liu, X.; Morrison, G. Blockchain-enabled Peer-to-Peer energy trading. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 94, 107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. Do clean energy stocks diversify the risk of FinTech stocks? Connectedness and portfolio implications. Glob. Financ. J. 2024, 62, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, N.; Alrababa’a, A.R.; Rehman, M.U.; Vo, X.V.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Portfolio risk and return between energy and non-energy stocks. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.; Galvão, R.; Cruz, S.; Irfan, M.; Alexandre, P.; Gonçalves, S.; Teixeira, N.; Palma, C.; Almeida, L. Testing the diversifying asset hypothesis between clean energy stock indices and oil price. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ameur, H.; Ftiti, Z.; Louhichi, W.; Yousfi, M. Do green investments improve portfolio diversification? Evidence from mean conditional value-at-risk optimization. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 94, 103255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Li, B.; Qin, Z. Spillovers and dependency between green finance and traditional energy markets under different market conditions. Energy Policy 2024, 192, 114263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Xiao, Y.; Duan, K.; Urquhart, A. Spillover effects between fossil energy and green markets: Evidence from informational inefficiency. Energy Econ. 2024, 131, 107317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, E.; I Cevik, E.; Dibooglu, S.; Cergibozan, R.; Bugan, M.F.; Destek, M.A. Connectedness and risk spillovers between crude oil and clean energy stock markets. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 3319–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yu, M.; Meng, J.; Jiang, Y. Examining the Spillover Effects of Renewable Energy Policies on China’s Traditional Energy Industries and Stock Markets. Energies 2024, 17, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, O.; Abosedra, S.; Sharif, A.; Alola, A.A. Dynamic volatility among fossil energy, clean energy and major assets: Evidence from the novel DCC-GARCH. Econ. Change Restruct. 2024, 57, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhadhbi, M. The interconnected carbon, fossil fuels, and clean energy markets: Exploring Europe and China’s perspectives on climate change. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian-Yazdi, F.; Roudari, S.; Omidi, V.; Mensi, W.; Al-Yahyaee, K.H. Contagion effect between fuel fossil energies and agricultural commodity markets and portfolio management implications. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 95, 103492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodell, J.W.; Yadav, M.P.; Ruan, J.; Abedin, M.Z.; Malhotra, N. Traditional assets, digital assets and renewable energy: Investigating connectedness during COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104323. [Google Scholar]

- Diebold, F.X.; Yılmaz, K. On the network topology of variance decompositions: Measuring the connectedness of financial firms. J. Econom. 2014, 182, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, T.; Greenwood-Nimmo, M.; Shin, Y. Quantile connectedness: Modeling tail behavior in the topology of financial networks. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 2401–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, I.; Nekhili, R.; Umar, M. Extreme connectedness between renewable energy tokens and fossil fuel markets. Energy Econ. 2022, 114, 106305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustaoglu, E. Extreme return connectedness between renewable energy tokens and renewable energy stock markets: Evidence from a quantile-based analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 5086–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.T.; Foley, A.M.; Nižetić, S.; Huang, Z.; Ong, H.C.; Ölçer, A.I.; Nguyen, X.P. Energy-related approach for reduction of CO2 emissions: A critical strategy on the port-to-ship pathway. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 355, 131772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, A.; Jena, P.K.; Bekun, F.V.; Sahu, P.K. Symmetric and asymmetric impact of economic growth, capital formation, renewable and non-renewable energy consumption on environment in OECD countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Mohsin, M.; Rasheed, A.K.; Chang, Y.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Public spending and green economic growth in BRI region: Mediating role of green finance. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S. Renewable energy policy trends and recommendations for GCC countries. Energy Transit. 2017, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.A.; Yousaf, I.; Karim, S.; Tiwari, A.K.; Farid, S. Comparing asymmetric price efficiency in regional ESG markets before and during COVID-19. Econ. Model. 2023, 118, 106095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosthuizen, M.A.; Inglesi-Lotz, R. The impact of policy priority flexibility on the speed of renewable energy adoption. Renew. Energy 2022, 194, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozgor, G.; Mahalik, M.K.; Demir, E.; Padhan, H. The impact of economic globalization on renewable energy in the OECD countries. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Viktor, P.; Al-Musawi, T.J.; Ali, B.M.; Algburi, S.; Alzoubi, H.M.; Al-Jiboory, A.K.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. The renewable energy role in the global energy Transformations. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 48, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, O.R.; Romagnoli, S. Financing sustainable energy transition with algorithmic energy tokens. Energy Econ. 2024, 132, 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Umar, M.; Naveed, M.; Shan, S. Assessing the impact of renewable energy tokens on BRICS stock markets: A new diversification approach. Energy Econ. 2024, 134, 107523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naifar, N. Interactions between renewable energy tokens, oil shocks, and clean energy investments: Do COP26 policies matter? Energy Policy 2025, 198, 114497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Xie, Q. Quantile frequency connectedness between energy tokens, crypto market, and renewable energy stock markets. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, N.L.; Gomes, L.L.; Brandão, L.E. A blockchain-based model for token renewable energy certificate offers. Rev. Contab. Finanças 2023, 34, e1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, O.; Cioara, T.; Anghel, I. Blockchain solution for buildings’ multi-energy flexibility trading using multi-token standards. Future Internet 2023, 15, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Rais, S. Time-varying spillover and the portfolio diversification implications of clean energy equity with commodities and financial assets. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2018, 54, 1837–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaarslan, B.; Soytas, U. Dynamic correlations between oil prices and the stock prices of clean energy and technology firms: The role of reserve currency (US dollar). Energy Econ. 2019, 84, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Liu, C.; Da, B.; Zhang, T.; Guan, F. Dependence and risk spillovers between green bonds and clean energy markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Naeem, M.A.; Balli, F.; Balli, H.O.; Vo, X.V. Time-frequency comovement among green bonds, stocks, commodities, clean energy, and conventional bonds. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 40, 101739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attarzadeh, A.; Balcilar, M. On the Dynamic Connectedness of the Stock, Oil, Clean Energy, and Technology Markets. Energies 2022, 15, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attarzadeh, A.; Balcilar, M. On the dynamic return and volatility connectedness of cryptocurrency, crude oil, clean energy, and stock markets: A time-varying analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 65185–65196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporale, G.M.; Spagnolo, N.; Almajali, A. Connectedness between fossil and renewable energy stock indices: The impact of the COP policies. Econ. Model. 2023, 123, 106273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.A.; Husain, A.; Bossman, A.; Karim, S. Assessing the linkage of energy cryptocurrency with clean and dirty energy markets. Energy Econ. 2024, 130, 107279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.; Huynh, T.L.D.; Hanif, W. Time-varying asymmetric spillovers among cryptocurrency, green and fossil-fuel investments. Glob. Financ. J. 2023, 58, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Q.; Huang, X.; Guo, L. Do green bonds and economic policy uncertainty matter for carbon price? New insights from a TVP-VAR framework. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 86, 102502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Umar, M.; Mirza, N.; Yue, X.-G. Green financing and resources utilization: A story of N-11 economies in the climate change era. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 78, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Meng, Q. Time and frequency connectedness and portfolio diversification between cryptocurrencies and renewable energy stock markets during COVID-19. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2022, 59, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-J.; Chiu, W.-Y.; Hua, W. Blockchain-enabled renewable energy certificate trading: A secure and privacy-preserving approach. Energy 2024, 290, 130110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Lucey, B. Do clean and dirty cryptocurrency markets herd differently? Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fang, F.; Ma, S.; Xiang, L.; Xiao, Z. Dynamic volatility spillover among cryptocurrencies and energy markets: An empirical analysis based on a multilevel complex network. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2024, 69, 102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Asymmetric link between energy market and crypto market. Int. J. Financ. Eng. 2024, 11, 2350038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcelebi, O.; El Khoury, R.; Yoon, S.-M. Interplay between renewable energy and fossil fuel markets: Fresh evidence from quantile-on-quantile and wavelet quantile approaches. Energy Econ. 2024, 140, 108012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, W.; Rehman, M.U.; Vo, X.V. Risk spillovers and diversification between oil and non-ferrous metals during bear and bull market states. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, W.; Vo, X.V.; Kang, S.H. Multiscale spillovers, connectedness, and portfolio management among precious and industrial metals, energy, agriculture, and livestock futures. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Lucey, B. A clean, green haven?—Examining the relationship between clean energy, clean and dirty cryptocurrencies. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 105951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Li, Y. Extreme quantile spillovers and drivers among clean energy, electricity and energy metals markets. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 86, 102474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H. Time-frequency spillovers among carbon, fossil energy and clean energy markets: The effects of attention to climate change. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusion Media. Investing.com Market Data Portal. 2023. Available online: https://www.investing.com (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Rogers, L.C.G.; Satchell, S.E. Estimating variance from high, low and closing prices. Ann. Appl. Probab. 1991, 1, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L.C.G.; Satchell, S.E.; Yoon, Y. Estimating the volatility of stock prices: A comparison of methods that use high and low prices. Appl. Financ. Econ. 1994, 4, 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, G.; Rothenberg, T.J.; Stock, J.H. Efficient Tests for an Autoregressive Unit Root; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Koop, G.; Korobilis, D. A new index of financial conditions. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2014, 71, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, G.; Pesaran, M.H.; Potter, S.M. Impulse response analysis in nonlinear multivariate models. J. Econom. 1996, 74, 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H.H.; Shin, Y. Generalized impulse response analysis in linear multivariate models. Econ. Lett. 1998, 58, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Yilmaz, K. Better to give than to receive: Predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers. Int. J. Forecast. 2012, 28, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M.; Kanjilal, K.; Dutta, A.; Uddin, G.S.; Ghosh, S. Can clean energy stock price rule oil price? New evidences from a regime-switching model at first and second moments. Energy Econ. 2021, 95, 105116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudeh, S.; Mokni, K.; Ben-Salha, O.; Ajmi, A.N. Distributional predictability between oil prices and renewable energy stocks: Is there a role for the COVID-19 pandemic? Energy Econ. 2021, 103, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) Returns | |||||

| ROIL | RPWR | RSPGCE | RWPR | RECO | |

| Mean | 0.016 | −0.113 | 0.064 | −0.49 | 0.046 |

| Median | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.13 |

| Variance | 11.844 | 68.815 | 3.299 | 84.283 | 7.4 |

| Skewness | −1.894 *** | −0.196 *** | −0.393 *** | −0.599 *** | −0.312 *** |

| Ex. Kurtosis | 50.826 *** | 7.212 *** | 6.649 *** | 14.158 *** | 3.355 *** |

| JB | 133,018.433 *** | 2671.285 *** | 2295.595 *** | 10,338.519 *** | 596.285 *** |

| ADF-GLS | −9.594 *** | −6.226 *** | −9.864 *** | −15.973 *** | −8.834 *** |

| N | 1229 | 1229 | 1229 | 1229 | 1229 |

| (b) Realized Volatility | |||||

| VECO | VWPR | VSPGCE | VPWR | VOIL | |

| Mean | 32.569 | 173.601 | 22.878 | 125.425 | 44.559 |

| Median | 26.787 | 105.615 | 18.669 | 85.894 | 36.738 |

| Variance | 561.037 | 654,454.869 | 266.665 | 28,645.557 | 1404.466 |

| Skewness | 2.189 *** | 21.657 *** | 2.590 *** | 7.319 *** | 6.897 *** |

| Ex. Kurtosis | 9.126 *** | 498.668 *** | 11.195 *** | 96.233 *** | 79.884 *** |

| JB | 5251.015 *** | 12,840,454.787 *** | 7798.390 *** | 485,595.607 *** | 336,800.076 *** |

| ADF-GLS | −6.400 *** | −14.932 *** | −5.717 *** | −12.521 *** | −6.272 *** |

| N | 1229 | 1229 | 1229 | 1229 | 1229 |

| (a) Returns Spillover | ||||||

| ROIL | RPWR | RSPGCE | RWPR | RECO | FROM | |

| ROIL | 85.13 | 1.68 | 5.05 | 1.30 | 6.84 | 14.87 |

| RPWR | 1.11 | 74.46 | 3.66 | 16.89 | 3.88 | 25.54 |

| RSPGCE | 3.34 | 2.57 | 55.38 | 1.72 | 36.99 | 44.62 |

| RWPR | 0.92 | 16.85 | 2.11 | 78.19 | 1.93 | 21.81 |

| RECO | 4.60 | 2.72 | 36.14 | 1.46 | 55.08 | 44.92 |

| Transmitted | 9.97 | 23.82 | 46.95 | 21.38 | 49.65 | 151.77 |

| Including own | 95.10 | 98.28 | 102.33 | 99.57 | 104.73 | cTCI/TCI |

| NET spillovers | −4.90 | −1.72 | 2.33 | −0.43 | 4.73 | 37.94/30.35 |

| (b) Realized Volatility Spillover | ||||||

| VECO | VWPR | VSPGCE | VPWR | VOIL | FROM | |

| VECO | 58.21 | 1.52 | 27.39 | 3.15 | 9.73 | 41.79 |

| VWPR | 1.76 | 70.20 | 1.60 | 7.08 | 19.36 | 29.80 |

| VSPGCE | 29.04 | 0.29 | 61.08 | 1.49 | 8.10 | 38.92 |

| VPWR | 5.25 | 8.48 | 3.81 | 74.48 | 7.98 | 25.52 |

| VOIL | 6.05 | 0.60 | 10.91 | 0.78 | 81.66 | 18.34 |

| Transmitted | 42.11 | 10.90 | 43.70 | 12.50 | 45.16 | 154.37 |

| Including own | 100.32 | 81.09 | 104.79 | 86.98 | 126.82 | cTCI/TCI |

| NET spillovers | 0.32 | −18.91 | 4.79 | −13.02 | 26.82 | 38.59/30.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Attarzadeh, A. The Dynamic Interplay of Renewable Energy Investment: Unpacking the Spillover Effects on Renewable Energy Tokens, Fossil Fuel, and Clean Energy Stocks. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219735

Attarzadeh A. The Dynamic Interplay of Renewable Energy Investment: Unpacking the Spillover Effects on Renewable Energy Tokens, Fossil Fuel, and Clean Energy Stocks. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219735

Chicago/Turabian StyleAttarzadeh, Amirreza. 2025. "The Dynamic Interplay of Renewable Energy Investment: Unpacking the Spillover Effects on Renewable Energy Tokens, Fossil Fuel, and Clean Energy Stocks" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219735

APA StyleAttarzadeh, A. (2025). The Dynamic Interplay of Renewable Energy Investment: Unpacking the Spillover Effects on Renewable Energy Tokens, Fossil Fuel, and Clean Energy Stocks. Sustainability, 17(21), 9735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219735