1. Introduction

In response to the significant environmental deterioration caused by traditional industrialization, a growing number of firms are voluntarily channeling resources into product R&D and innovation as part of their corporate sustainability initiatives [

1,

2]. A prime example is Tesla voluntarily channels billions of dollars into R&D specifically to create innovative products that solve environmental challenges, proving that market-leading success can be achieved through a sustainability-first innovation strategy. The development of their electric vehicles, from the Model S to the Cybertruck, represents a continuous, voluntary investment in R&D to create a zero-emission alternative to internal combustion engine vehicles, directly addressing the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions [

3].

However, on the demand side, consumer behavior presents a notable dichotomy. On the one hand, there are green-conscious consumers who translate their environmental principles into deliberate purchasing decisions [

4,

5]. In contrast, on the other hand, although a vast majority of consumers are aware of and concerned about environmental issues, their actual purchasing habits often fail to reflect this awareness—these are non-green-conscious consumers [

6]. For instance, while surveys indicate that over 90% of people are interested in sustainable products, their actual engagement in sustainable practices has stagnated over the past five years. Research suggests that this discrepancy is primarily driven by financial barriers, as higher prices for sustainable goods continue to hinder consumer adoption and enthusiasm, particularly in some regions and markets [

7].

To reconcile this divergence and overcome the barriers, green education is posited as a pivotal intervention, as it not only improves consumers’ efficiency in acquiring and evaluating information [

8], but also enhances their capability and willingness to consider recommended options [

6,

9,

10]. The practical implementation of this educational function is most effectively embodied by retailers, as they can alleviate consumer doubts and encourage a greater willingness to pay a premium through in-store demonstrations, eco-label explanations, and guided sampling [

11,

12]. The strategic application of this educational model is exemplified by retailer leaders. Walmart, for instance, translates its sustainability goals into clear eco-label explanations, while leveraging its physical presence to offer tangible in-store demonstrations and guided sampling [

13,

14]. This multi-pronged strategy serves to effectively address the barriers to environmental purchasing, thereby reducing consumer hesitation within its extensive base of 230 million weekly customers [

15].

However, upon exposure to retailers’ green education, consumer trust in green claims exhibits significant variation. According to the Blue Yonder Consumer Sustainability Survey, while 55% of consumers report that their trust depends on the specific brand, message, or company history, there are notable differences in perceptions of companies’ green education efforts. Specifically, respondents in France (25%), the US (23%), the UK (17%) and ANZ (13%) are more likely to believe that companies genuinely use green education initiatives in their advertising and marketing [

16]. From a research perspective, the key question is whether profit-maximizing retailers should implement green education to ensure comprehensive information delivery to non-green-conscious consumers, and if so, what implications such efforts would have.

To answer this question, we conceptualize the retailer as an “educator and promoter” for product R&D, aiming to bridge the demand-side gap. More specifically, consistent with the practices of Walmart, we model the retailer engaging in green education targeted at non-green-conscious consumers by providing clear product explanations and improving their willingness to pay for sustainable products. It is crucial to note, however, that the retailer’s motivation for such education is profit maximization, not altruistic environmental responsibility. This theoretical model leads us to our first research question:

Does the retailer’s green education positively influence the manufacturer’s green innovation efforts and market adoption of green products?

Our analysis confirms that while the retailer’s green education can increase the levels of product R&D and the market adoption of green products under certain conditions, it fails to unlock the full potential for growth in these areas. This is because the retailer, driven by profit maximization, only implements education strategies within a range that is beneficial to itself. In other words, there exists a region where green education could further enhance product R&D and adoption, but the retailer forgoes it because doing so does not contribute to profit. This phenomenon—the inherent tension between a retailer’s individual profit maximization and overall environmental performance—is known as the ‘consumer education paradox’.

The paradox exposes a critical conflict: while it highlights a retailer’s limited environmental stewardship, it also signals significant, complex repercussions for the supply chain. To fully understand these consequences, we further examine the paradox’s impact on supply chain partners, leading to our second research question:

Does the retailer’s green education facilitate the manufacturer’s profitability?

Our analysis further uncovers a dual effect of the retailer’s green education, leading to either ‘win–win’ or ‘win–lose’ outcomes for the retailer and manufacturer. The latter outcome is particularly noteworthy as it reflects the retailer’s inherent profit-maximizing behavior, resulting in the retailer’s gain coming at the manufacturer’s expense. To put it another way, the ‘win–lose’ outcome emerges because the retailer strategically deploys green education to capture a greater share of the supply chain value, which in turn directly diminishes the manufacturer’s net profitability.

As the consumer education paradox brings to light a fundamental conflict spanning retailer profit, environmental performance, and manufacturer profitability, this tension ultimately informs our final research question:

What mechanisms can be employed to resolve the consumer education paradox?

To resolve the consumer education paradox, we examine two government subsidy methods with distinct policy objectives: one focused on increasing the quantity of green products, and the other on incentivizing product R&D. Our analysis confirms that while both interventions are effective in alleviating the Consumer Education Paradox, they differ significantly in their fiscal implications. Specifically, although green innovation subsidies require considerably greater government financial commitment to achieve effectiveness, they consistently demonstrate superior effectiveness in fostering higher green innovation levels and green adoption.

This paper proceeds as follows:

Section 2 summarizes the related literature.

Section 3 formulates models for both scenarios with and without green education.

Section 4 presents our key findings, and

Section 5 provides concluding discussions.

2. Relevant Literature

A significant strand of literature relevant to our study addresses consumer education. In particular, Bai et al. [

8] showed that the manufacturer prefers to partially integrate a component supplier only when the efficiency of its energy conservation investment is neither too low nor too high. Sun and Yuan [

17] suggested that if allowing the flexibility of remanufacturing outsourcing, consumer education on green consumption introduces opportunities for opportunistic behaviors that can compromise both profitability and environmental objectives. Zhong et al. [

18] indicated that a new product seller (E-retailer) can benefit from the remanufactured goods’ cannibalization in the Agency channel. Wang et al. [

19] revealed that increasing the warranty and education levels will not always improve the firm’s profitability. Sun and Liu [

20] revealed that government subsidy policies effectively encourage original equipment manufacturers to enter remanufacturing, while consumer education primarily benefits independent remanufacturers despite not always benefiting OEMs. Abdulla et al. [

21] argued that, while consumer education about the remanufacturing process fails to increase appeal and willingness to pay for remanufactured products, providing physical exposure significantly enhances both by increasing perceived quality and decreasing disgust. Florea et al. [

22] identified customer education in B2B firms as a three-stage process involving preparation, deployment, and measurement, advancing its understanding as a cross-functional capability that requires coordination across multiple stakeholders. Previous studies have highlighted consumer education’s role in improving information acquisition and evaluation but have not addressed the key question of whether profit-maximizing retailers should implement green education to ensure comprehensive information delivery to non-green-conscious consumers. Therefore, we complement this research by examining whether a retailer’s profit-motivated consumer education can enhance green R&D and production.

The second stream of literature related to our study focuses on green innovation. For example, Xie et al. [

23] showed that the moderating effect of green subsidies on the relationship between green product innovation and a firm’s financial performance is not supported. Then, Abadzhiev et al. [

24] identified three distinct innovation activity configurations at the company level and three alignment mechanisms along the value chain. However, Lin and Lin [

25] proposes a novel algorithm for computing network reliability in multistate supply chain networks that integrates supplier sustainability to enhance green innovation through sustainable supplier selection and equitable order allocation. Ai et al. [

26] showed that while excessive leverage creates risk accumulation that harms financial outcomes with strategic and substantive green innovations. Subsequently, Quadir et al. [

27] found that information sharing improves greening levels when manufacturers are efficient, with Bertrand competition yielding higher greening levels and consumer surplus than Cournot competition, while Lambrecht et al. [

28] revealed that relying solely on patent and trademark data to identify green innovative firms leads to significant exclusion of such firms, with green trademarks serving as an effective indicator of green product innovation. While substantial research has examined product R&D, our study distinguishes itself through two key aspects: First, unlike existing studies that assume all consumers are environmentally conscious, we identify a significant segment of non-green-conscious consumers who are deterred by perceived high costs and lack of reliable information. Second, we address the previously unexplored question of whether profit-maximizing retailers should implement green education to ensure comprehensive information delivery to these non-green-conscious consumers.

The final stream of literature indirectly related to our research focuses on government subsidy policies. Azevedo et al. [

29] constructed a real options framework to analyze how governmental subsidies and taxation policies influence investment timing and scale. Wang et al. [

30] employed a Stackelberg model to examine three government subsidy mechanisms—for manufacturers’ eco-design, retailers’ sales effort, and consumers’ green consumption—demonstrating that retailer subsidies are the least favorable from social welfare and environmental standpoints. Guo et al. [

31] explored carbon quota mechanisms and used battery recycling subsidies as alternatives to expiring purchase subsidies and maladapted dual credit policies for China’s new energy vehicle development. Corsini [

32] reviewed the study that identifies twelve leverage points and policy recommendations for enabling building components reuse as a circular economy approach. Chen and Keppo [

33] examined how government subsidies for data collection interact with voluntary and centralized data sharing among firms. Although previous studies have not focused on retailer green education strategies, they have demonstrated that among various policy tools, green innovation subsidy and green product subsidy are particularly effective, inspiring our research to reconcile the trade-offs between profit-motivated consumer education, product R&D, and adoption stemming from green education.

Table 1 provides the contributions through comparison with the related research.

3. Model

Consistent with Sun et al. [

34] and Yang et al. [

35], we assume that consumers, with a total mass normalized to one, are vertically heterogeneous according to their valuation of

. The supply side features a manufacturer who invests in product R&D, enhancing product greenness

at a cost of

. Comparable functional forms are extensively employed in green supply chain models examining R&D effort responses [

1,

6,

36]. Notably, this product R&D generates two distinct market segments, reflecting a consumer behavior dichotomy driven by varying valuations of the green attribute

: Green-conscious consumers with a full valuation of

, are incentivized to purchase sustainable products. In contrast, non-green-conscious consumers, constrained by information asymmetry, possess a discounted valuation of

. Like Yang et al. [

35], Smith and Shulman [

37], Nire and Matsubayashi [

38], research suggests that similar hesitation discounts have been widely used in the vertical differentiation models of consumer willingness-to-pay. That is, like them, we also allow firms, e.g., Walmart, to translate the efforts to overcome the barriers by providing clear eco-label explanations, while leveraging its physical presence to offer tangible in-store demonstrations and guided sampling [

13,

14].

Accordingly, like Olsder et al. [

39], Yang et al. [

35] and Sun et al. [

17], we then can model the consumer’s purchasing decision with the following utility function:

Then, green-conscious consumers will purchase the product if , while non-green-conscious consumers will do so if , respectively, where represents price sensitivity. As such, green-conscious consumers will purchase the product when , while non-green-conscious consumers will do so for . Since the mass of consumers in the market is normalized to one, the utility function yields the following demand functions for green-conscious consumers and for non-green-conscious consumers.

Let

represent the fraction of non-green-conscious consumers, with the remaining fraction,

being green-conscious consumers. Then, without green education, the demand function is given by

Notably, although the retailer’s green education can overcome the discounted valuation of among non-green-conscious consumers, it would incur an additional cost of per unit.

3.1. Setting (A): Without Green Education

We begin by establishing a benchmark scenario in which the retailer does not engage in green education. The game unfolds as follows: Stage 1 (Manufacturer): The manufacturer sets the product greenness level () and the wholesale price (). Stage 2 (Retailer): After observing the manufacturer’s decisions, the retailer subsequently determines the final retail price ().

Formally, adopting backward induction, the retailer’s problem is defined as follows:

Substituting the optimal demand

from (3) into the retailer’s profits, maximizing the retailer’s problem provides

:

Anticipating the retailer’s optimal response, the manufacturer chooses greenness

and the wholesale price

to maximize her profits:

Performing the maximization in (5) yields

and

:

By substituting them into

,

,

and

, we derive the equilibrium outcomes for setting A. These results are formally presented in the lemma that follows (All proofs are provided in the Online

Appendix A).

Lemma 1.

When the retailer’s role is limited to distribution and does not include green education, both parties choose the following optimal decisions:

3.2. Setting (B): With Green Education

Recall that if the retailer undertakes green education, she incurs an additional cost of

. This effort, however, offsets the negative impact of the valuation discount

on demand,

. Similar assumptions can also be found in the literature, which looks at process improvement decisions (see, e.g., Yang et al. [

35], Arya et al. [

40], and Yang et al. [

41]).

Since the retailer adopts a green education strategy, its problem can be rewritten as:

Maximizing the retailer’s problem provides

Observing

, the manufacturer chooses

and

to maximize her profits:

Solving the problems in (8) yields

and

Substituting them into

,

,

and

, provides the equilibrium outcomes for setting B in the following lemma (the proof is provided in the Online

Appendix B).

Lemma 2.

When the retailer undertakes distribution and also provides green education, both parties make the following optimal decisions:

4. Main Results

To clarify the influence of the retailer’s green education, we conduct a comparative analysis of the optimal outcomes presented in

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2, focusing on its effects on both parties’ strategic choices and financial performance.

The initial finding indicates that the effectiveness of retailers’ green education depends on specific conditions related to its implementation (the proof is provided in the Online

Appendix C).

Proposition 1. The retailer undertakes green education if and only if .

Proposition 1 is consistent with the conventional wisdom that cost management is fundamental to corporate success, positing that profitability and long-term viability are contingent upon a firm’s ability to effectively control its expenditures [

42]. Specifically, as

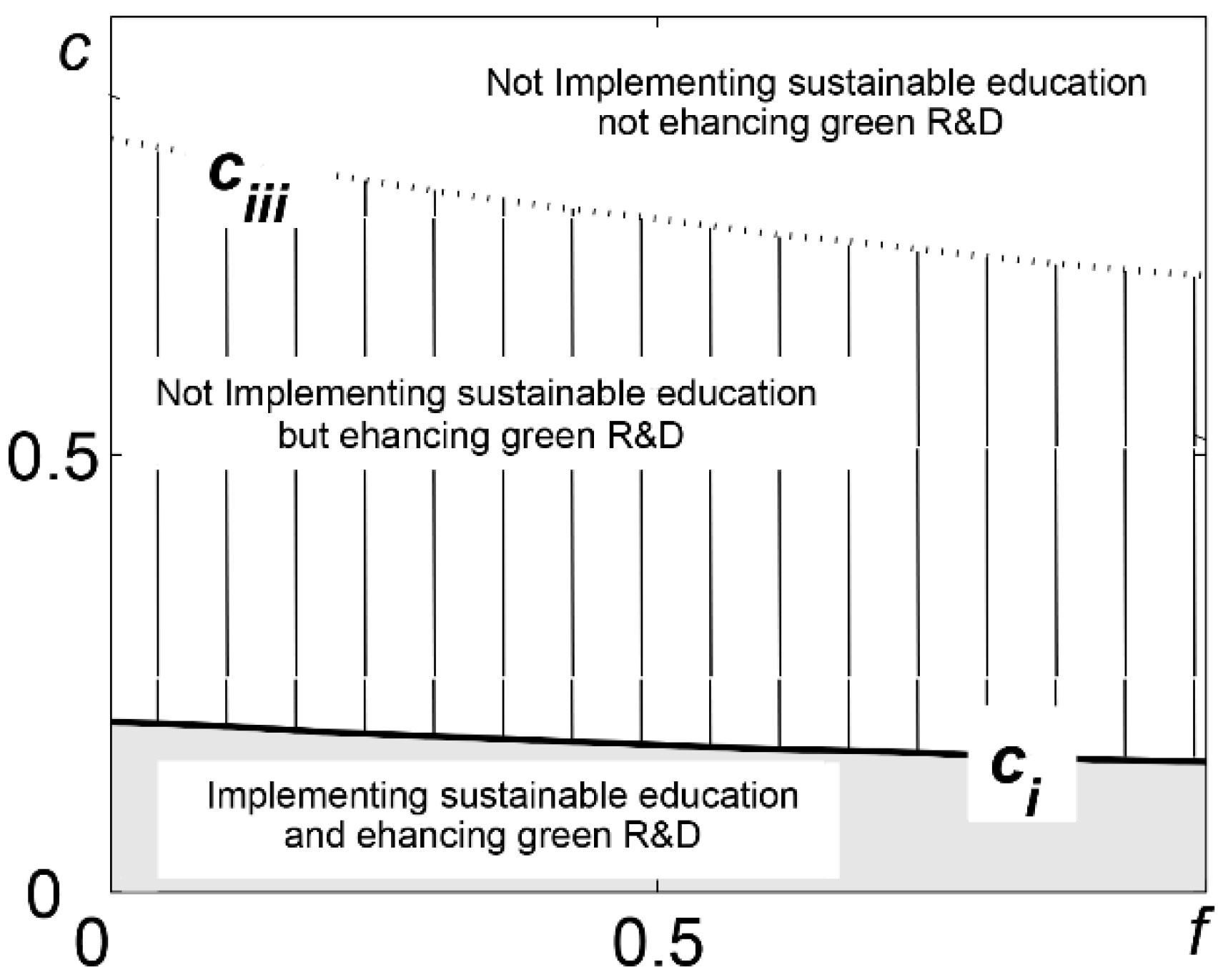

Figure 1a indicates, the retailer will opt to provide green education when the associated cost

is less than

, as this strategy yields a superior profit (

). Conversely, for costs exceeding the threshold (

), the retailer forgoes green education because the profit from doing so is inferior to the alternative (

).

Note that, although the retailer’s green education can mitigate the valuation discount effect in non-green-conscious consumers, it incurs an additional cost of

. Consequently, with higher proportions of non-green-conscious consumers, green education becomes a more challenging and costly task. Therefore, as

Figure 1b demonstrates, there is a negative relationship between the fraction of non-green-conscious consumers and retailer green education implementation (

). On the other hand, since the retailer’s green education effectively modifies the non-green-conscious consumers’ utility function from

to

, the higher valuation discount of

allows retailers to capture potential profits due to higher consumer premiums obtained from this segment. Thus, as

Figure 1 demonstrates, we find that the opposing directional relationship holds between the cost threshold

and the discounted valuation

, yielding

(See

Figure 1c).

From Proposition 1, we find that although the retailer undertakes green education within a certain range to offset the negative impact of the valuation discount among non-green-conscious consumers, the retailer’s decision-making remains driven by profit maximization. Thus, it is essential to examine the effects of the retailer’s green education on its optimal quantity decisions, as well as on the manufacturer’s product R&D investment and profitability.

The following proposition analyzes how the retailer’s green education influences green adoption in the market (the proof is provided in the Online

Appendix D).

Proposition 2. The retailer’s green education enhances green adoption (i.e., ) if and only if ; conversely, when , the opposite holds true.

Ma et al. [

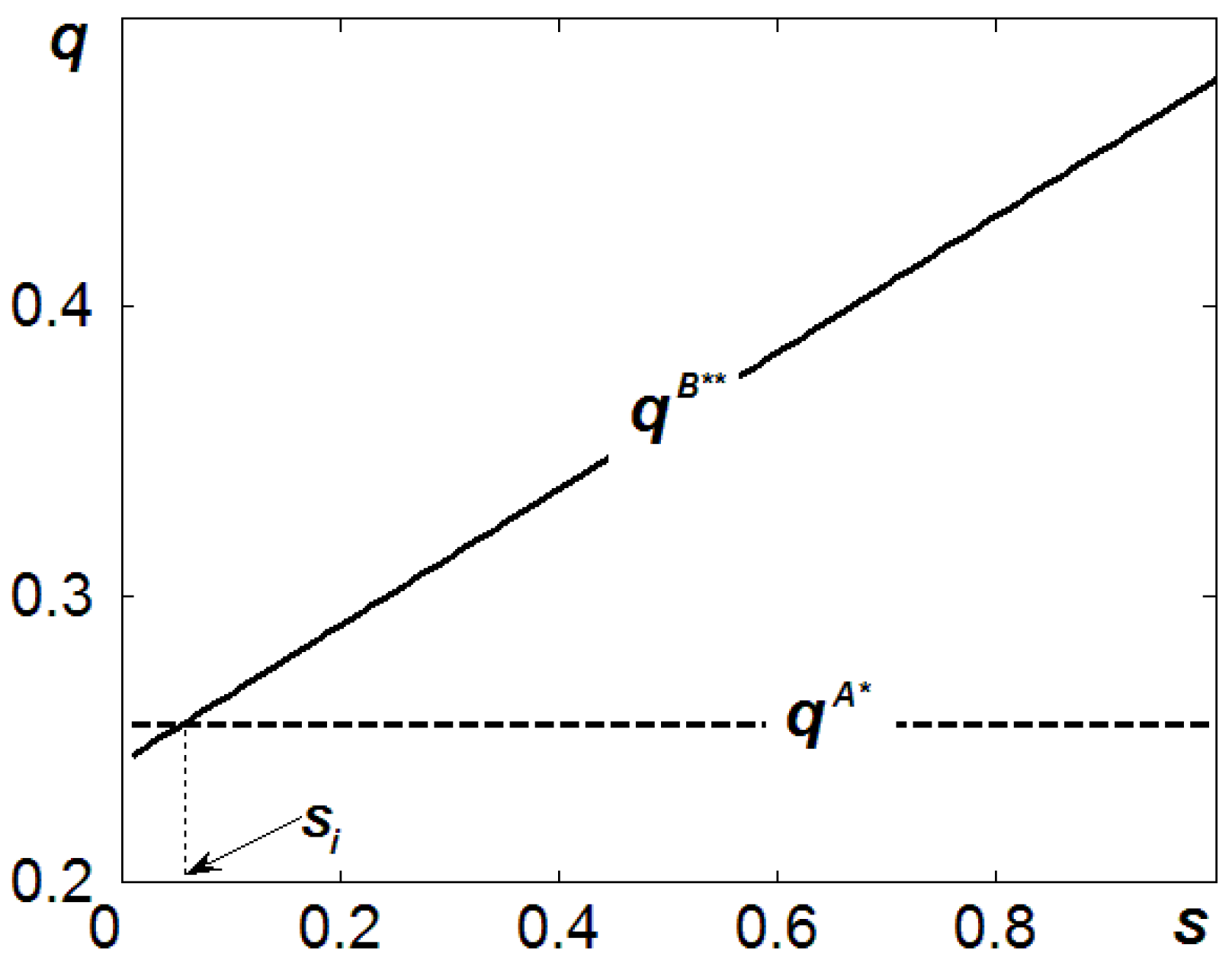

43] have revealed that consumer adoption is crucial for the profitability of new products, because it directly influences market penetration rates and creates economies of scale in adoption and distribution. In contrast to the singular profit focus of conventional new product adoption, researchers have established that green adoption not only exerts similar influences on stakeholder profitability but also pursues broader objectives of economic ecological transition and environmental sustainability. In particular, Proposition 2 reveals the consumer education paradox, wherein the retailer’s green education does not necessarily lead to increased sales of green products: while confirming that the retailer’s green education leads to higher product volumes (

) when

, we surprisingly find that the retailer’s green education may result in relatively lower consumer adoption when

. Furthermore, as

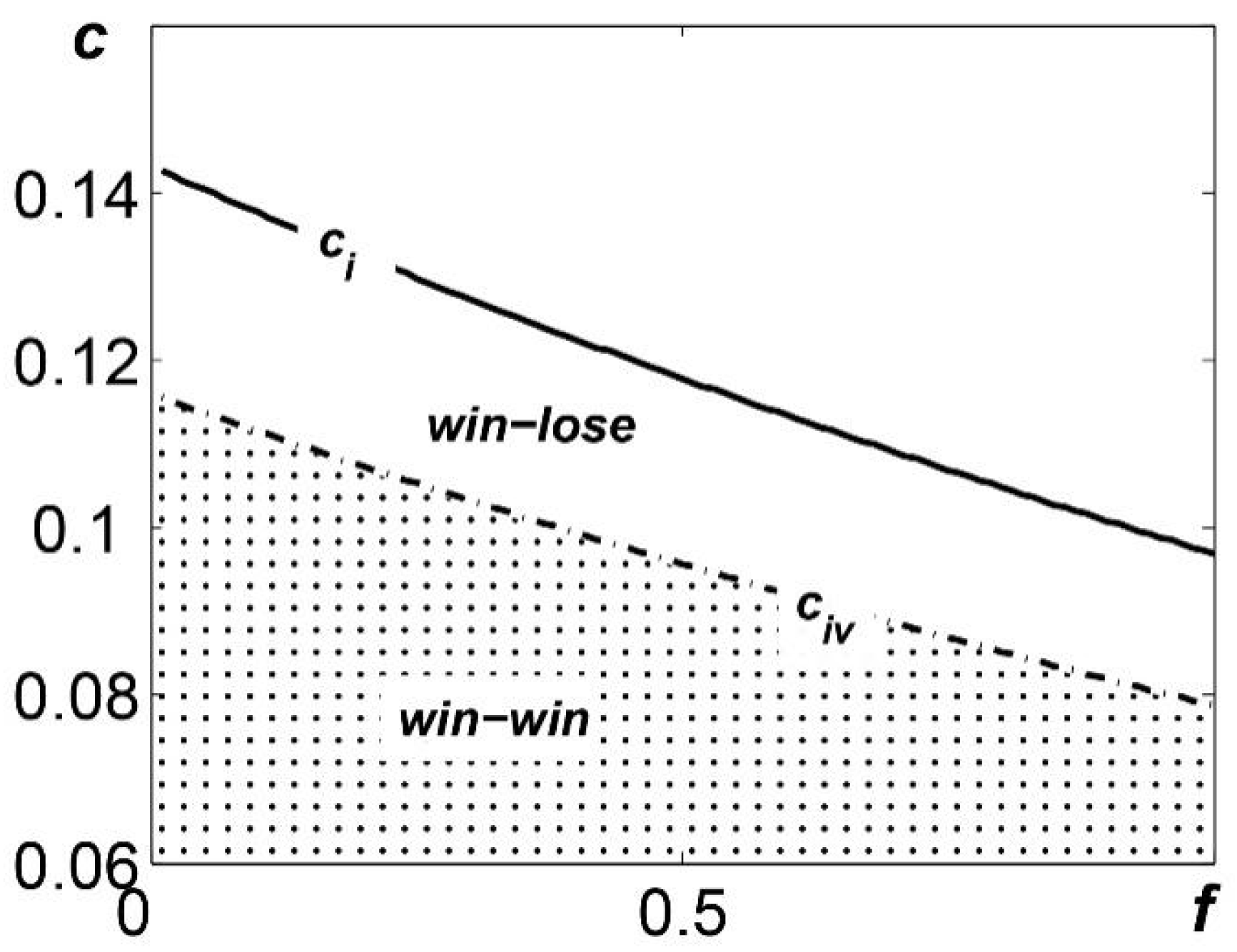

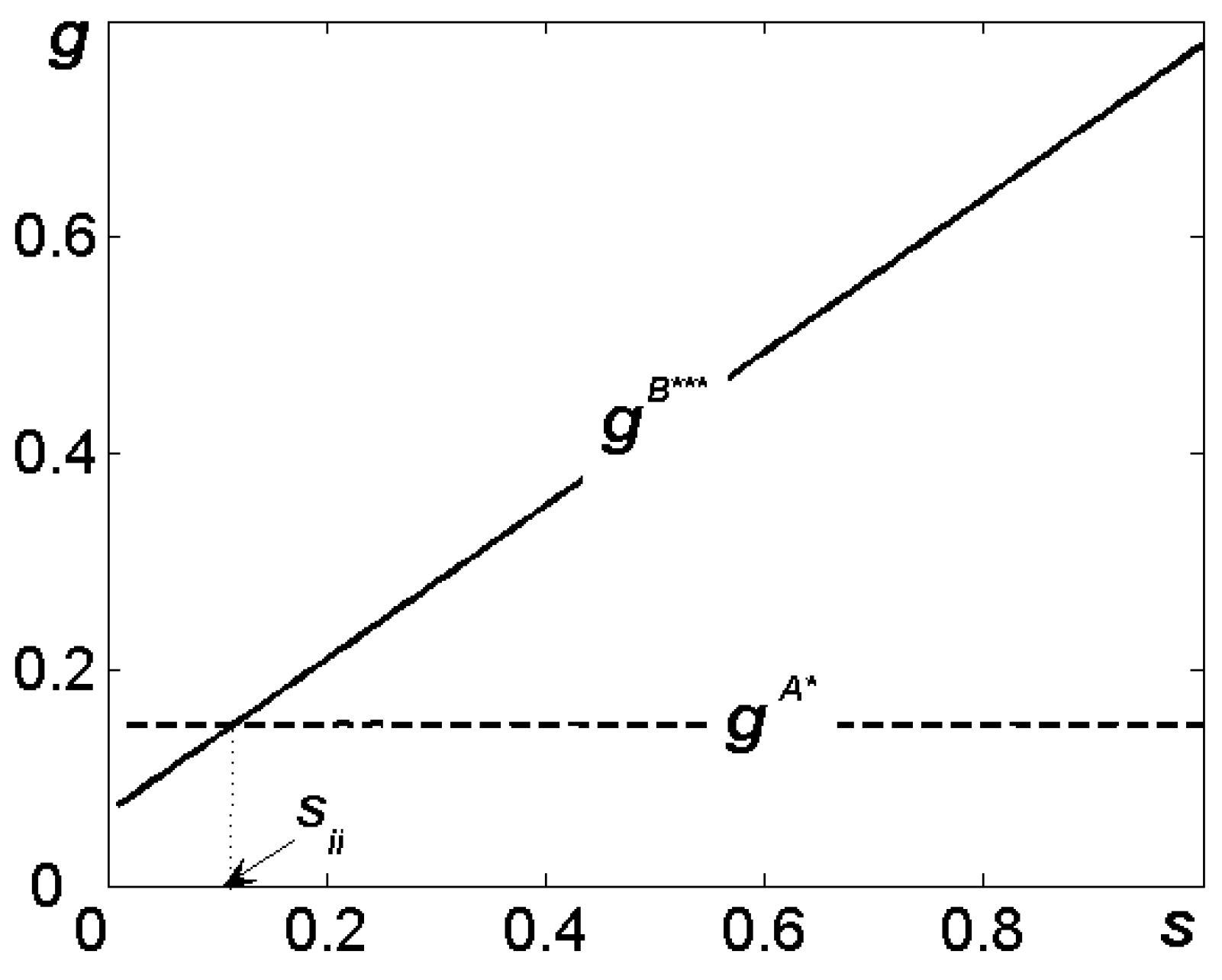

Figure 2 shows, since

, we can conclude that, although green education can increase sales volumes for

, the retailer undertakes green education if and only if

. That is, to maximize profits, the retailer only secures part of the potential gains that could boost green adoption, not all of them.

The reasons behind the consumer education paradox in green adoption stem from the retailer’s profit-maximizing behavior. Specifically, when the green education cost is pronounced (

), the retailer must increase the selling price to cover the expense and maintain an appropriate margin. This price increase necessarily results in lower green adoption (

). Furthermore, although green education can increase sales volumes for

, the retailer forgoes this strategy in this interval because it does not contribute to profit maximization (see

Figure 2).

Having considered the consumer education paradox in green adoption, we now take a further step to examine whether the retailer’s green education positively influences the manufacturer’s green innovation efforts—a question addressed in the following proposition (the proof is provided in the Online

Appendix E).

Proposition 3. The retailer’s green education enhances the manufacturer’s green innovation if and only if ; conversely, when , the opposite holds true.

Beyond its importance in profit maximization, green innovation serves as a critical tool for combating the substantial deterioration of the global environment. In particular, Chen et al. [

1] found that the degree of green innovation achieved by a manufacturer is determined by its product R&D investment efficiency and spillover, as well as its power relationship with other supply chain actors. Proposition 3 partially validates this conclusion, particularly finding that when the green education cost is not pronounced, i.e.,

, the retailer’s green education enhances the manufacturer’s green innovation. This enhancement occurs because the retailer’s green education eliminates information asymmetry among non-green-conscious consumers and overcomes their discounted valuation of

. Then, when green education costs are not significant (

), the retailer is willing to share a portion of the profits from non-green-conscious consumers with the manufacturer through higher wholesale prices. Faced with this wholesale price premium, the manufacturer is incentivized to increase its degree of green innovation, resulting in

.

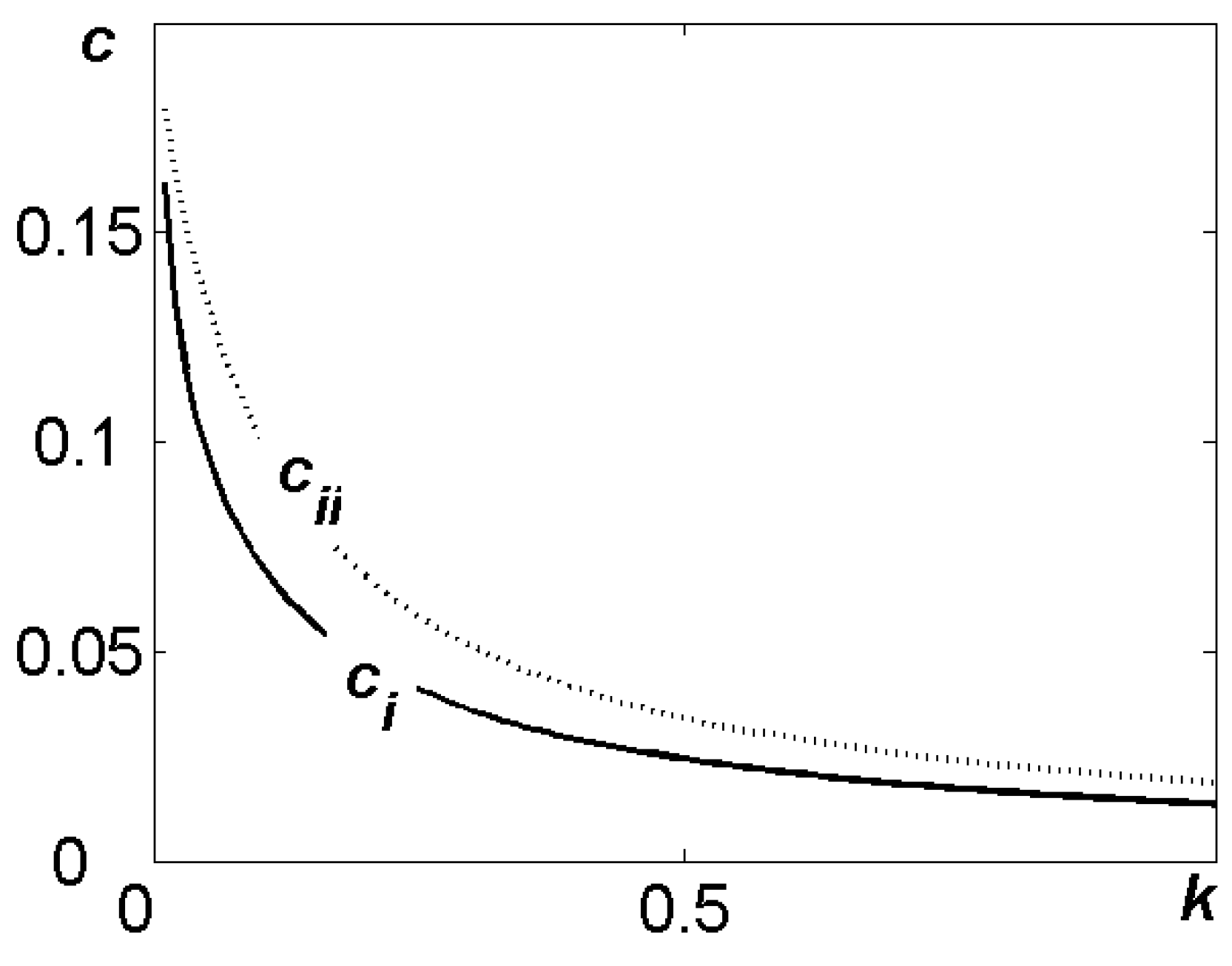

It should be noted that, as

Figure 3 shows, Proposition 3 reveals the second consumer education paradox: although green education can increase product R&D when

, retailers forgo this strategy in this interval because it does not contribute to profit maximization. Our findings indicate that while retailer consumer education can enhance product R&D levels and adoption under specific conditions, it does not fully realize the growth potential in these domains. That is, the retailer’s consumer education paradox inherent tension between a retailer’s individual profit maximization and overall product R&D and adoption. It should be noted that for the sake of simplicity, we use product adoption and the level of R&D as proxies for ‘environmental performance’ and ‘sustainability.’ Of course, interested readers may refer to Sun and Yuan [

17] and Agrawal et al. [

44] for more direct measures, such as emissions or ecological footprint, which are calculated as quantity multiplied by unit emissions.

This paradox reveals a key tension: it underscores the retailer’s limited environmental stewardship while indicating complex supply chain repercussions. To grasp these effects, we examine if the retailer’s green education enhances manufacturer profitability (the proof is provided in the Online

Appendix F).

Proposition 4. The retailer’s green education enhances the manufacturer’s profitability if and only if

; conversely, the opposite holds true

Proposition 4 illustrates the retailer’s strategic approach to using green education for capturing supply chain value, which results in different outcomes.

Figure 4 shows that the first scenario occurs when education costs are low (

), where the retailer’s green education boosts manufacturer profitability (

) by sharing profits from non-green-conscious consumers. In contrast, the second scenario emerges when education costs are high (

), causing the retailer’s green education to reduce manufacturer profitability (

) as profit-sharing is eliminated. The third observation, based on the relationship

, indicates that green education creates ‘win–win’ outcomes when

, but transitions to ‘win–lose’ outcomes when

.

Propositions 2, 3, and 4 yield the observation below.

Observation 1. For profit-maximizing:

- (i)

The retailer’s green education captures partial, not total, sustainable gains from green adoption and innovation.

- (ii)

This education may diminish the manufacturer’s profitability.

Observation 1, which follows directly from Propositions 1, 2, 3 and 4, reveals that, for profit-maximizing, through green education, the retailer triggers the Consumer Education Paradox, which establishes a fundamental conflict between the retailer’s profit and the environmental performance.

6. Conclusions

Previous studies in consumer education have established its dual benefits: enhancing consumers’ efficiency in information acquisition and evaluation and strengthening their capacity and inclination to consider recommended alternatives [

6,

48]. A critical gap remains, however, as these investigations neglect to address that the ‘educator and promoter’ motivation is fundamentally profit-maximizing rather than environmentally altruistic. This research intends to highlight whether profit-driven retailers should implement green education to ensure comprehensive information reaches non-green-conscious consumers, and what consequences such educational efforts might entail.

More specifically, we model a supply chain where the manufacturer conducts product R&D while the retailer distributes products to two distinct consumer segments. Green-conscious consumers translate environmental principles into purchasing decisions, while non-green-conscious consumers are deterred by perceived high costs and information deficits. The retailer engages in green education targeted at non-green-conscious consumers, providing clear product explanations to improve their willingness to pay for sustainable products. Crucially, the retailer’s motivation for this education is profit maximization, not altruistic environmental responsibility.

From theoretical perspectives, our paper addressed a gap in the literature and yielded several contributions to the aforementioned literature. First, we complement the previous studies, including Sun et al. [

20], Abdulla et al. [

21] and Florea et al. [

22], by addressing the question of whether profit-maximizing retailers should implement green education to ensure comprehensive information delivery to non-green-conscious consumers. Second, following Zhou et al. [

6], we also identify the consumer education paradox but distinguish our research by highlighting a significant segment of non-green-conscious consumers who are deterred by perceived high costs and lack of reliable information. Third, to resolve this, we analyze two government subsidy methods: one targeting green product quantity and the other promoting product R&D.

From practical perspectives, our analysis provided several important insights for both retail managers and policymakers seeking to promote sustainable consumption. For example, our analysis confirms that there exists a region where green education could further enhance product R&D and adoption, but the retailer forgoes it because doing so does not contribute to profit. This phenomenon—the inherent tension between a retailer’s individual profit maximization and overall environmental performance—is known as the ‘consumer education paradox’. Second, our analysis further uncovers a dual effect of the retailer’s green education, leading to either ‘win–win’ or ‘win–lose’ outcomes for the retailer and manufacturer. The latter outcome is particularly noteworthy as it reflects the retailer’s inherent profit-maximizing behavior, resulting in the retailer’s gain coming at the manufacturer’s expense. Finally, our analysis confirms that while both interventions are effective in alleviating the Consumer Education Paradox, they differ significantly in their fiscal implications. Specifically, although green innovation subsidies require considerably greater government financial commitment to achieve effectiveness, they consistently demonstrate superior effectiveness in fostering higher green product innovation levels and adoption.

Future research could address several limitations of our study. First, we focused solely on mathematical interpretation involving the division of consumers into two groups—‘green-conscious’ and ‘non-green-conscious’—which creates opportunities for empirical studies to be conducted using real-world data. Second, our assumption that retailers’ green education can overcome consumer discounted valuation at a per-unit cost doesn’t fully account for how effectiveness varies with educator efforts [

49], suggesting potential research into alternative cost structures. Third, while we proposed green product and innovation subsidies to address the consumer education paradox, we neglected other remedies such as green credit policies, environmental regulations, and non-green product taxes. Examining these alternatives could broaden the applicability of our results. Finally, future research could explore alternative explanations or practical implementation challenges, such as alternative game-theoretic approaches (e.g., Nash bargaining), empirical validation (e.g., calibration to Walmart data), dual-purpose retailers (e.g., pursuing both profit and social welfare), or multi-supplier dynamics (e.g., Walmart’s interactions with multiple suppliers).