4.1. Recommendations

We recommend the following disability-inclusive climate policies and programming in response to our research findings. The government, together with key stakeholders, must raise awareness at the nexus of disability and climate change [

3,

53]. Storytelling, trainings, and cultural events will build capacity on disability and climate change, shift attitudes, and catalyze disability-inclusive climate action. Providing accessible information on disability and climate change will enable and facilitate inclusive climate-related decision-making [

3,

53]. Good practice examples include the New Media Advocacy Project’s awareness raising campaign on disability and climate change in the Niger Delta, and the CCD’s training sessions for persons with disabilities on disability and climate change [

7].

The government, together with key stakeholders, must act urgently to propel inclusive disaster risk reduction. Early warning systems, accessible shelters, and accessible transport are vital to protecting the rights to life and health of persons with disabilities in disasters, and as mandated by the CRPD and Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, among other international instruments [

37,

54]. Enabling inclusive early warning systems also aligns with the UN’s Early Warnings for All initiative [

55]. The inclusion of persons with disabilities in leadership and decision-making is vital to propel disability-inclusive disaster risk reduction. In Abia State, a one-day capacity-building workshop on disability-inclusive disaster management practices brought together key stakeholders, including representatives from the State Emergency Management Agency, Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Health, and organizations of persons with disabilities [

56]. This inclusive multisectoral approach is an important model for promoting disability-inclusive disaster management at the state and national level. The Federal Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development has a mandate and opportunity to ensure disability inclusion in emergency preparedness, response, and recovery [

57]. Further evidence-based research is required to determine how to reduce disaster risk for heterogenous disabilities as well as intersectionally [

3].

Disability-inclusive sustainable agricultural training is required to enable farmers with disabilities to adapt to climate change, enhance agricultural productivity, and food security [

15,

16]. Climate policies and programs must ensure that farmers with disabilities are targeted for inclusion in sustainable agricultural [

15]. Providing reasonable accommodations for trainings will increase access to disability-inclusive sustainable agriculture. Further, staff implementing agricultural programs must be trained in disability inclusion [

15]. These measures are particularly vital in Abia North. Persons with disabilities facing challenges achieving agricultural productivity may benefit from adaptive agricultural tools and practices and access to a broader range of agricultural-related livelihood, such as food processing.

In Nigeria, farmers are utilizing two broad approaches to adapt to climate change: local and Indigenous Knowledge and climate-smart agriculture. Root and tuber production is increasing in Nigeria, despite climate change, demonstrating that farmers are using Indigenous Knowledge to grow crops including cassava, yam, sweet potato and cocoyam to co-exist with climate change [

58]. Indigenous practices in Kwara State include mulching, intercropping, herbs to debar insects, and the planting of animal repellents to protect farms from cows and monkeys [

58]. Farmers viewed these practices as effective, readily available, and inexpensive. By contrast, a top-bottom approach by scientists can result in the development of solutions that did not consider the economic capacity or the cultural values of farmers, and could lead farmers to be dependent on outside support when faced with worsening climate change [

58]. A study in southeast Nigeria of household farmers found that they had adopted climate-smart agricultural and sustainable practices such as planting well-adapted crops and crop rotation [

59]. Research indicates that climate-smart agriculture in Nigeria can increase agricultural productivity and food security [

59]. Studies in sustainable agriculture, however, largely exclude farmers with disabilities or do not report findings related to this group. Consequently, further research is urgently required on how farmers with disabilities can successfully utilize or adopt sustainable agricultural practices. For sustainable agricultural practices to be adopted by farmers with disabilities they require inclusive training in Indigenous and local practices or climate-smart agriculture, and access to resources including finance. CBM India has provided accessible training to farmers with disabilities on enhancing soil resiliency and decreasing the usage of polluting agrochemicals [

60].

Disability-inclusive sustainable livelihood opportunities can be increased through inclusive and subsidized vocational training, apprenticeships, and mentoring [

2,

16]. “Green” skills training can include innovative climate responses and inherently sustainable vocational opportunities such as traditional crafts and teaching. People with disabilities must be included in nature-based solutions programs to protect, restore, conserve, or sustainably use ecosystems [

61]. In Abia State, this includes erosion control, gully stabilization, and mangrove restoration. Awareness raising campaigns, particularly in Abia South, can highlight erosion and catalyze community involvement in climate adaptation responses. Enhancing access to clean energy may increase decent livelihood opportunities for people with disabilities. For example, access to off-the-grid powered assistive technology could expand small business opportunities [

62]. Government policies supporting inclusive vocational training will increase disability-inclusive sustainable livelihoods. Further socio-economic assessment is required, particularly in Abia North, and research with organizations of persons with disabilities on lessons learned from farmers, workers, underemployed and unemployed with disabilities to identify successful targeted sustainable income-generating interventions.

Social networks can also heighten access to disability-inclusive livelihoods, and may increase knowledge of sustainable agricultural practices; and consequently, agricultural productivity [

15]. In the surveyed area, persons with disabilities belonged to representative organizations including the National Association of the Blind, Nigeria National Association of the Deaf, National Association of Persons with Physical Disabilities, Spinal Cord Injury Association of Nigeria, and Albinism Association of Nigeria which provide capacity building on disability and peer support. However, persons with disabilities are largely not included in farming cooperatives or small business organizations, nor have they formed their own entities. Such social networks could provide valuable mentorship opportunities.

Disability-inclusive livelihoods can be catalyzed by expanding access to inclusive finance through Village Savings and Loans Associations linked to climate adapted livelihoods programs and microfinance [

63]. Assistance in accessing documentation required for financial services, such as birth certificates and land certificates, would enhance the access of persons with disabilities to financial resources. Anti-discrimination training among microfinance and banking professionals would advance inclusive financial services.

The government must commit to increasing the employment of persons with disabilities through inclusive green skill training, quotas, tax incentives, wage replacement, public sector hiring, reasonable accommodations, mentoring, retention, and better implementation of legal protections against employment discrimination [

64]. Underrepresented persons with disabilities, such as persons with albinism and hearing disabilities, must be included in these interventions, as must persons facing intersectional discrimination such as women with disabilities [

64]. The public sector would benefit from employing a greater percentage of persons with disabilities who bring unique perspectives and talents, including lived experience as problem solvers. Simultaneously, employing this untapped pool of workers with disabilities will advance transformation toward an inclusive sustainable society. The government and trade unions can also promote decent work conditions for informal workers with disabilities.

Underrepresented persons with disabilities facing significant stigma and marginalization must be included in climate decision-making, policies, and interventions. The Deaf-Blind, persons with hearing disabilities, albinism, and intellectual disabilities, and leprosy survivors are among the disability subgroups facing significant marginalization and thus must be specifically consulted in decision-making, referenced and included in mainstream and targeted climate policies and solutions. Providing sign language translation in sustainable agricultural and vocational trainings would expand disability-inclusive livelihood opportunities in D/deaf communities. Expanding the provision of indoor livelihoods and sunscreen for persons with albinism would advance their health adaptation, livelihood, and wellbeing. Ensuring that livelihood training is inclusive of persons with intellectual disabilities, and providing information in easy read formats, would increase access to livelihood opportunities for these individuals.

The voices of persons with disabilities facing intersectional discrimination must also be heard in climate decision-making. In this study, all genders overwhelmingly perceive poverty, agricultural productivity, and livelihood as high threats, with males providing a slightly higher response. Gender responsive and disability-inclusive local solutions must be developed to ensure that climate solutions meet the needs of all genders by undertaking consultations with disability organizations that recognize underlying power dynamics and develop safe spaces [

3]. Women and girls with disabilities, for instance, benefit from well-lighted and accessible public spaces, and separate accessible toilets and sleeping spaces in internally displaced persons and related camps [

60].

Disability stigma and discrimination are barriers to livelihood and financial inclusion which must be addressed through cultural attitude change campaigns [

2]. Success stories demonstrating that persons with disabilities can earn livelihoods and educational qualifications can break down cultural and structural barriers. Training programs for key stakeholders on disability rights will advance implementation of the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018, enabling the enshrined rights to be realized [

34]. Importantly, persons with disabilities and their representative organizations must be empowered to meaningfully participate in climate-related decision-making as mandated by the CRPD [

2,

3,

37].

Persons with disabilities in Abia State and across Nigeria face barriers to healthcare equity such as a scarcity of assistive devices, which are costly and mostly available in cities; the out-of-pocket cost of disability-related healthcare and medicine; inaccessible infrastructure, equipment, and information; and a lack of training among healthcare workers [

57]. Disability equity must be advanced in healthcare by developing climate-related disability-inclusive policies; assuring the accessibility of infrastructure in (re)construction projects; undertaking disability rights and awareness training and multisectoral engagement with organizations of persons with disabilities; heightening the availability of assistive devices and medicine; and ensuring the inclusivity of digital health and climate information and technology [

11]. Co-designing and locally producing assistive technology may increase both the availability, accessibility, and effectiveness of such technology. These climate measures require inclusive budgeting and must be supported through international cooperation and technology transfer [

37].

Migrants with disabilities experience overlapping barriers and nuanced social marginalization, disparate water and food insecurity, violence, inaccessible water, sanitation, and hygiene, shelter, and transportation, along with enhanced opportunities [

3,

65]. Moreover, internal displacement due to the nexus of climate change and conflict can led to injury, torture, and disability. Nigeria’s National Policy on Internally Displaced Persons addresses internally displaced persons with disabilities, including their right to a modified physical environment, assistive devices, specialist medical care, and priority in water and food distribution; however better implementation is required, which would be enabled by further resources, attitudinal change, and capacity building [

65,

66]. Inclusive concrete climate measures can promote disability-inclusive livelihood diversification, accessible infrastructure, land-use planning, and mitigate gender-based violence. These climate solutions are particularly required in Abia North. Further assessments and research are required to identify highly affected communities, including in Abia South, and to identify how communities are benefiting from and affected by climate-induced migration challenges.

Urbanization can catalyze the inclusion of persons with disabilities. International commitments such as SDG 11 seek to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable” [

39]. In Banjarmasin, Indonesia an urban accessible community space for educating children, healthcare services, and activism, was co-designed through collaboration with organizations of persons with disabilities [

60].

Participants with disabilities in this study identified disability-inclusive locally led climate adaptation and mitigation as a key climate priority. In Abia State and across Sub-Saharan African, disability groups face significant barriers to climate resources and decision-making. Inclusive locally led adaptation funding would empower these groups to advance climate resilient development within their communities.

Social protection is a vital tool for addressing climate-related shocks, poverty, and inequity, including disability inequity [

3]. Implemented responsive social protection would enable individuals with disabilities in Abia State to adapt and respond to climate change. Positively, Nigeria’s updated Nationally Determined Contribution specifies that social protection coverage should extend to persons with disabilities [

36]. There is growing recognition by international institutions and national policymakers of the importance of climate-related social protection [

61]. Inclusive social protection is mandated by the CRPD to ensure an adequate standard of living for persons with disabilities [

3,

37]. Internationally, disability spending has been growing in the social protection sector, for instance, countries such as Zambia have scaled up cash transfers [

60].

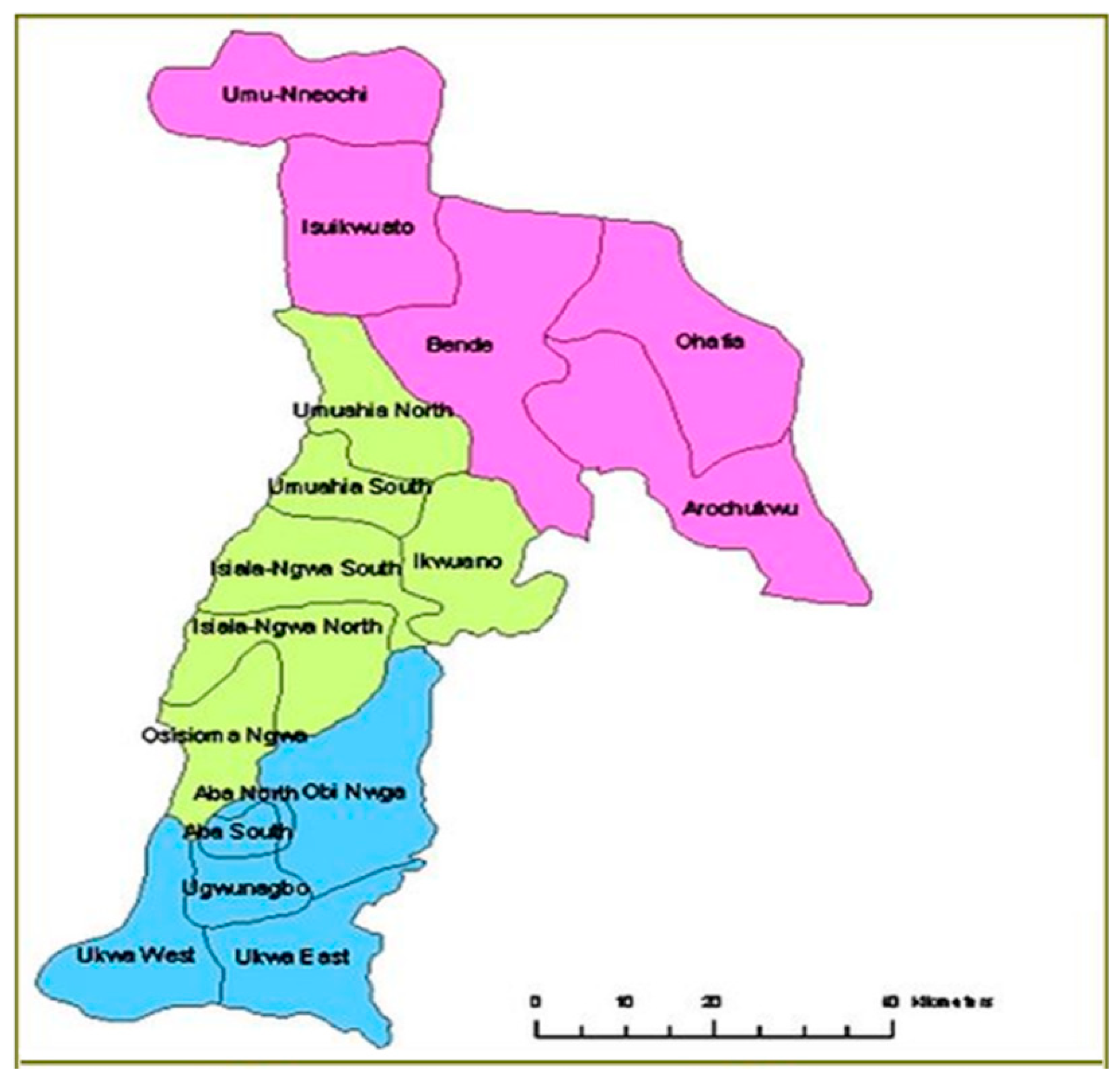

Heightening inclusive climate finance in Abia State, particularly in the Abia North and Abia Central senatorial zones, that significantly enhances the implementation of inclusive climate measures such as early warning systems, disaster preparedness plans, livelihood training, village cooperatives, and ecosystem restoration initiatives, would contribute to the region’s inclusive climate resilient development. Furthermore, inclusive climate finance would promote collaboration among stakeholders, empowering intersectionally marginalized groups, and advancing social equity.

Moving forward, the government must ensure that climate plans, policies, and programs respect, protect, and fulfill disability human rights. In a twin-track approach to inclusive climate action, persons with disabilities are included in climate interventions across all sectors equally, while targeted solutions respond to the unique challenges faced by this group [

3]. Fully utilizing the meaningful participation and leadership of persons with disabilities and their representative organizations in climate adaptation and mitigation planning, policies, and responses will combat climate-related human rights harms [

2]. Advancing implementation of inclusive climate approaches in line with domestic and international law necessitates inclusive climate financing. This is ultimately less costly than exclusionary measures that subsequently require retrofitting in order to reach highly impacted communities [

2]. Inclusive monitoring, evaluation, and learning are vital to enhancing inclusive climate action [

3]. Importantly this enables stakeholders, including government agencies and community leaders, to be held accountable for their actions or inactions in addressing disability-inclusive climate action, fostering transparency and accountability in inclusive climate response efforts. Inclusive locally led climate adaptation and mitigation catalyze community involvement and can promote innovative culturally appropriate solutions. We urge key stakeholders to precipitate a paradigm shift that empowers persons with disabilities, promotes disability equity, and advances inclusive climate justice.