Anthropocentric or Biocentric? Socio-Cultural, Environmental, and Political Drivers of Urban Wildlife Signage Preferences and Sustainable Coexistence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Anthropocentric vs. Biocentric Framings

1.3. Research Gap

1.4. Objectives and Contribution

2. Literature Review and Background

2.1. Urban-Wildlife Encounters in the Anthropocene Era

2.2. Wild Boars as an Urban Environmental Challenge

2.3. Environmental Morality Policies

2.4. Thinning of Invasive Species and Regulations Against Feeding Wild Animals

2.5. Anthropocentric vs. Biocentric Views

2.6. Urban Signage as a Political and Environmental Discourse

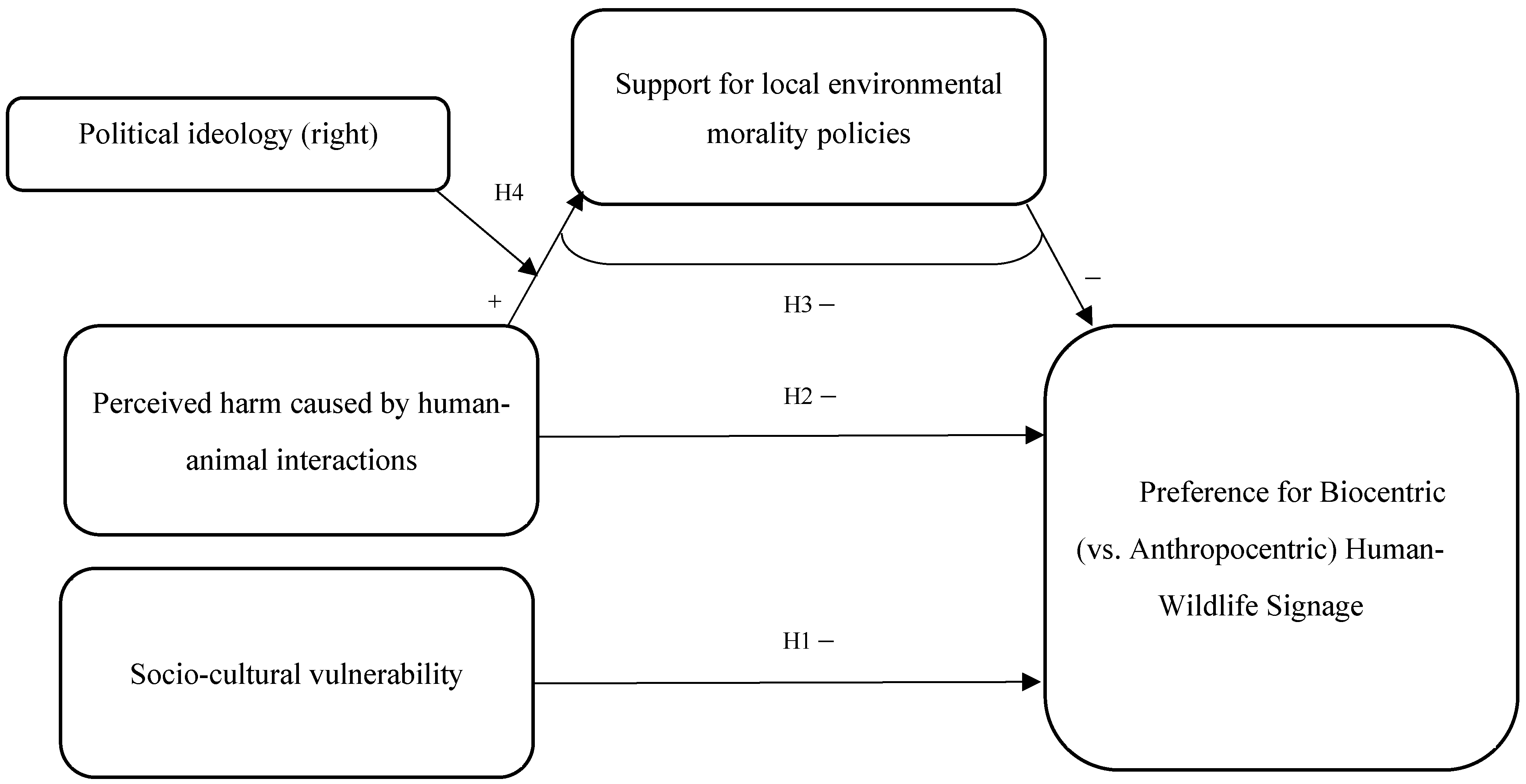

3. Developing Hypotheses: Socio-Cultural, Environmental, and Political Drivers of Anthropocentric vs. Biocentric Wildlife Signage

3.1. Socio-Cultural Factors and Preference for Anthropocentric vs. Biocentric Human–Wildlife Signage

3.2. Environmental Factors and Preference for Anthropocentric vs. Biocentric Human–Wildlife Signage

3.3. Political Factors: The Mediation Role of Environmental Morality Policies

3.4. Political Factors: The Moderation Role of Political Ideology

4. Method

4.1. Nesher Municipality and the Challenge of Sustainable Coexistence with Wild Boars

4.2. Wild Boars in Mount Carmel and Nesher: Environmental–Political Insights

4.3. Survey Design, Sample, Procedure and Ethics

5. Measures

- (i)

- Participants were asked to describe the primary content and message of a sign, assuming the Municipality of Nesher decides to install signage related to wild boars.

- (ii)

- The researcher analyzed the responses and categorized them into three groups: 1 = Anthropocentric—Participants who framed wild boars as a threat and emphasized warnings for pedestrians and drivers. Examples include: “Notice: Wild Boar Ahead;” “A red circle with a wild boar inside;” “Dangerous wild boars roam in the area, do not approach and report immediately.” 2 = Neutral—Participants who focused on appropriate human behavior to ensure the well-being of wild boars. Examples include: “Please do not leave trash or feed wild boars;” “Anyone caught will be severely punished;” “A surveillance camera is recording;” “Feeding animals is prohibited;” “Information on behavior guidelines for interacting with wild boars.” 3 = Biocentric—Participants who emphasized wild boars’ rights, advocated for their respectful treatment, and accepted their presence in the urban environment. Examples include: “The boar is not an enemy, but a wild animal searching for food;” “Wild boars are an integral part of the city’s natural and environmental ecosystem—they are not our enemies;” “Wild boars in this area. Preserve urban nature and coexistence.”

- (iii)

- We examined the correlation between the coding of the signage descriptions and five additional questions related to signage attributes. Our findings indicate that a preference for biocentric signage (higher score) aligns with: A preference for installing signs rather than avoiding them; A preference for instructional or informational signs rather than warning or prohibition signs; A preference for light and soft colors (light blue, greenish, gray, purplish) rather than bright and vivid colors (red, orange, yellow, black); A preference for an illustration of a family of wild boars rather than a full-body or head-only depiction of a wild boar; A preference for a humorous illustration rather than a realistic depiction.

- (iv)

- We coded all six questions on a scale from 1 to 3 and averaged respondents’ answers, creating an index of human–wildlife signage preference, where higher values indicate a biocentric perspective, and lower values indicate an anthropocentric perspective. The choice to code design-oriented variables on a 1–3 scale was both theoretically and empirically motivated. From a theoretical standpoint, prior research on environmental worldviews often conceptualizes anthropocentric and biocentric orientations as categorical poles along a spectrum, with a neutral middle ground. From an empirical standpoint, our pilot test indicated that respondents consistently distinguished among these three categories, but finer gradations produced inconsistent responses. Using a 1–3 ordinal scale therefore provided a parsimonious and interpretable coding scheme, while subsequent reliability and factor analyses confirmed that the items cohered into a single construct.

Statistical Procedures

6. Findings

6.1. H1: Socio-Cultural Factors

6.2. H2: Environmental Factors

6.3. Political Factors: H3 & H4

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Measurement Tool

| Perceived harm caused by wild boars (1 = Totally disagree to 5 = Totally agree) |

| The wild boar phenomenon in Nesher damaged me personally. The phenomenon of wild boars in Nesher damaged my family & friends. The phenomenon of wild boars in Nesher damaged the quality of life of the Nesher community as a whole. |

| Political ideology (1 = far left to 7 = far right) |

| Many people talk about left and right in politics. Please indicate where you would place yourself on the left-right spectrum |

| Support for local environmental morality policies |

| Please indicate the extent of your support or opposition to the described policy, ranging from −4 = completely opposed to +4 = completely supportive |

| Support for Thinning To address the wild boar issue, the Nesher Municipality should approve the culling of wild boars by shooting; … cull rogue wild boars that enter the urban area; … also cull wild boar piglets; …also cull pregnant and nursing wild boar. |

| Support for Regulation Against Wild-Animal Feeders |

| To address the wild boar issue, the Nesher Municipality should increase supervision of those feeding wild boars; … raise fines for those feeding wild boars; … encourage resi-dents to report wild boar feeders to the 106 hotline; lead a campaign against feeding wild boars. |

| Preference for biocentric (vs. anthropocentric) human–wildlife signage |

| If the Municipality of Nesher decides to install signs related to wild boars, what do you think should be the primary content and message of the sign(s)? What should be written or illustrated on them? Please elaborate as much as possible. _______________ What is your opinion regarding the placement of signs related to wild boars in Nesher? A. I prefer that signs related to wild boars be installed in Nesher. B. I prefer that signs related to wild boars not be installed in Nesher. Which type of sign would you prefer? A. Instructional sign (typically a blue circle) B. Warning and caution sign (typically a red triangle) C. Prohibition and restriction sign (typically a red circle) D. Informational and guidance sign (typically a rectangular shape) E. Warning sign (typically a yellow diamond) What do you think would be the most appropriate color scheme for the sign? A. Bright and vivid colors: red, orange, yellow, black B. Light and soft colors: light blue, greenish, gray, purplish Which illustration do you think should appear on the sign? A. A family of wild boars B. A full-body depiction of a wild boar (from head to foot) C. A wild boar’s head What do you think should be the illustration style of the sign? A. Realistic illustration (most similar to reality) B. Humorous illustration |

References

- Acuto, M.; Parnell, S.; Seto, K.C. Building a global urban science. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeri, I. The Effect of Environmental and Political Factors on Support for Local Environmental Morality Policies: Thinning, Trap–Neuter–Return and Regulation Against Wild-Animals’ Feeders. City Environ. Interact. 2025, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.; Brownlow, A.; Lassiter, U. Constructing the animal worlds of inner-city Los Angeles. In Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations; Philo, C., Wilbert, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bourban, M. Eco-Anxiety and the Responses of Ecological Citizenship and Mindfulness. In The Palgrave Handbook of Environmental Politics and Theory; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, V.E.; Thornton, A. Animal cognition in an urbanised world. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 633947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeri, I.; Sadetzki, Y.; Hirsch-Matsioulas, O. Non-human political agency: Human-wild animal interactions and urban conflict. Public Adm. Rev. 2024, 85, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassiola, J.J. The Environmental Political Role of Counter-Hegemonic Environmental Ethics: Replacing Human Supremacist Ethics and Connecting Environmental Politics, Environmental Political Theory and Environmental Sciences. In The Palgrave Handbook of Environmental Politics and Theory; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J. Animals in the study of public administration. Public Adm. Rev. 2022, 82, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apfelbeck, B.; Jakoby, C.; Hanusch, M.; Steffani, E.B.; Hauck, T.E.; Weisser, W.W. A conceptual framework for choosing target species for wildlife-inclusive urban design. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, N. Cities and Nature: Conceptualizations, Normativity and Political Analysis. In The Palgrave Handbook of Environmental Politics and Theory; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M.K.; Magle, S.B.; Gallo, T. Global trends in urban wildlife ecology and conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 261, 109236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterba, J. Nature Wars: The Incredible Story of How Wildlife Comebacks Turned Backyards into Battlegrounds; Crown: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, R.H.; Gonçalves, J.E.; Slingerland, G.; Kleinhans, R.; Prang, H.; Brazier, F.; Verma, T. Cities for citizens! Public value spheres for understanding conflicts in urban planning. Urban Stud. 2024, 61, 1327–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beeri, I. Who Suffers the Most? Wild Boars, Perceived Harm, and Local Politics: Governance Challenges in Urban Human-Wildlife Conflicts. Cities 2025, 165, 106083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.R.; Hobbs, R.J. Conservation where people live and work. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 16, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.L.; Zavattaro, S.M.; Battaglio, R.P.; Hail, M.W. Global reflection, conceptual exploration, and evidentiary assimilation: COVID-19 viewpoint symposium introduction. Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 80, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, R. Wildlife conservation and the moral status of animals. Environ. Politics 1994, 3, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, K.; Nair, S.; Ahamad, A. Studying light pollution as an emerging environmental concern in India. J. Urban Manag. 2022, 11, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinga, J.; Murúa, M.; Gelcich, S. Exploring perceptions towards biodiversity conservation in urban parks: Insights on acceptability and design attributes. J. Urban Manag. 2024, 13, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moesch, S.S.; Jeschke, J.M.; Lokatis, S.; Peerenboom, G.; Kramer-Schadt, S.; Straka, T.M.; Haase, D. The frequent five: Insights from interviews with urban wildlife professionals in Germany. People Nat. 2024, 6, 2091–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, B. Boar Wars: How Wild Hogs Are Trashing European Cities; The Guardian: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/30/boar-wars-how-wild-hogs-are-trashing-european-cities (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Salazar, G.; Satheesh, N.; Ramakrishna, I.; Monroe, M.C.; Mills, M.; Karanth, K.K. Using environmental education to nurture positive human–wildlife interactions in India. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2024, 6, e13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catlaw, T.J.; Holland, T.M. Regarding the animal: On biopolitics and the limits of humanism in public administration. Adm. Theory Prax. 2012, 34, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philo, C.; Wilbert, C. Animal spaces, beastly places: An introduction. In Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations; Philo, C., Wilbert, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, L.A.; Remer, K.M. Best practices in local animal control ordinances. State Local Gov. Rev. 2017, 49, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. A review on political factors influencing public support for urban environmental policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 75, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Hughes, K. Using front-end and formative evaluation to design and test persuasive bird feeding warning signs. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, A.; Milfont, T.L. Who cares? Measuring environmental attitudes. In Research Methods for Environmental Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Marchini, S. Who’s in conflict with whom? Human dimensions of the conflicts involving wildlife. In Applied Ecology and Human Dimensions in Biological Conservation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Crutzen, P.J.; McNeill, J.R. The Anthropocene: Are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature? AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2007, 36, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissenburg, M. The rapid reproducers paradox: Population control and individual procreative rights. Environ. Politics 1998, 7, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, P.; Brooks, A. Animals and urban gentrification: Displacement and injustice in the trans-species city. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 45, 1490–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, J. Who owns the future city? Phases of technological urbanism and shifts in sovereignty. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 1732–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.L.; Rosales Chavez, J.B.; Brown, J.A.; Morales-Guerrero, J.; Avilez, D. Human—Wildlife interactions and coexistence in an urban desert environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch-Matsioulas, O. Homo Homini Canis Est—Human-Canine Relations and Politics of Belonging on a Greek Island. Ph.D. Thesis, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheba, Israel, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Treichler, J.W.; VerCauteren, K.C.; Taylor, C.R.; Beasley, J.C. Changes in wild pig (Sus scrofa) relative abundance, crop damage, and environmental impacts in response to control efforts. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 4765–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórski, T.; Lusseau, D.; Scandura, M.; Sönnichsen, L.; Jȩdrzejewska, B. Long-lasting, kin-directed female interactions in a spatially structured wild boar social network. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisselquist, R.M. Good Governance as a Concept, and Why This Matters for Development Policy. In Foreign Aid: Research and Communication (Recom); Working Paper No. 2012/30; FIN; United Nations University: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cimpoca, A.; Voiculescu, M. Patterns of human–brown bear conflict in the urban area of Brașov, Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Building sustainable habitats for free-roaming cats in public spaces: A systematic literature review. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2023, 26, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J. Why Did the Turtle Cross the Street? An examination of herpetofauna habitat road fragmentation. In Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning; University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries: Amherst, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Masilkova, M.; Ježek, M.; Silovský, V.; Faltusová, M.; Rohla, J.; Kušta, T.; Burda, H. Observation of rescue behaviour in wild boar (sus scrofa). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Luque-Ayala, A.; McFarlane, C.; MacLeod, G. Enhancing urban autonomy: Towards a new political project for cities. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euchner, E.M. Morality Politics in a Secular Age: Strategic Parties and Divided Societies in Comparative Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, C.Z. The Public Clash of Private Values: The Politics of Morality Policy; Chatham House Publishers: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, J.K. Contraceptive vaccines for the humane control of community cat populations. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011, 66, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.C.; Pei, D.; Kotcher, J.E.; Myers, T.A. Predicting responses to climate change health impact messages from political ideology and health status: Cognitive appraisals and emotional reactions as mediators. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 1095–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, R.L. The ethics of species eradication. In The Ethics of Species: An Introduction; Sandler, R.L., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 154–178. [Google Scholar]

- Simberloff, D. Biological invasions: What’s worth fighting and what can be won? Ecol. Eng. 2014, 65, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzluff, J.M.; Angell, T. The Company of Crows and Ravens; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lippert, R.; Sleiman, M. Ambassadors, business improvement district governance and knowledge of the urban. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contalbrigo, L.; Normando, S.; Bassan, E.; Mutinelli, F. The welfare of dogs and cats in the European Union: A gap analysis of the current legal framework. Animals 2024, 14, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobetska, N.; Danyliuk, L. Implementation of the provisions of the European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals in Ukraine: Theoretical and applied aspects. Stud. Iurid. Lublinensia 2022, 31, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Prugh, L.R. Predators in Our MidstUrban Carnivores: Ecology, Conflict, and Conservation; Gehrt, S.D., Riley, S.P.D., Cypher, B.L., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulos, G. Diagrammatics of spatial justice: Neoliberalisation, normativity, and the production of space. Antipode 2022, 54, 1986–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syse, K.V.L. Stumbling over animals in the landscape: Methodological accidents and anecdotes. NJSTS 2014, 2, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, A.I.C. Local ecological knowledge about human-wildlife conflict: A Portuguese case study. Port. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 18, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo; Routledge and Keegan Paul: Oxfordshire, UK, 1966; pp. 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenborn, B.R.P.; Bjerke, T.; Nyahongo, J. Living with problem animals—Self-reported fear of potentially dangerous species in the Serengeti Region, Tanzania. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2006, 11, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Shelby, L.B.; Needham, M.D. Animal-Related Risk Perception and Management in Human-Wildlife Interactions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hitzhusen, G.E.; Tucker, M.E. The potential of religion for Earth Stewardship. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K. Remaking more-than-human society: Thought experiments on street dogs as “nature”. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2019, 44, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, R. A view from the concrete jungle: Diverging environmentalisms in the urban Caribbean. New West Indian Guide 2006, 80, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Miller, C.A.; McLean, H.E.; Jaebker, L.M. Beliefs, perceived risks and acceptability of lethal management of wild pigs. Wildl. Res. 2020, 48, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, W.J.; de Boer, F.W. The historical dynamics of social–ecological traps. Ambio 2014, 43, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treves, A.; Karanth, K.U. Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.; Chen, X.; Geng, Y.; Yang, K. Does regional collaborative governance reduce air pollution? Quasi-experimental evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, C.M. Pastoral, Progressive, and Postmodern Ideas in Environmental Political Thought: Restoring Agency to Nature. Adm. Theory Prax. 2001, 23, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Pattberg, P. Global Environmental Governance: Taking Stock, Moving Forward. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008, 33, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M.; Dunlap, R.E. Challenging global warming as a social problem: An analysis of the conservative movement’s counter-claims. Soc. Probl. 2000, 47, 499–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dispensa, M.J.; Brulle, R.J. Media’s social construction of environmental issues: Focus on global warming—A comparative study. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2003, 23, 74–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS). Regional Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/publications/Pages/2025/Local-Authorities-Statistical-Abstract-of-Israel-2025-No-76.aspx (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- State Comptroller of Israel. The Challenges of Local Authorities in Coping with Wild Boars and Jackals in Urban Areas; State Comptroller Report No. 402; State Comptroller’s Office: Jerusalem, Israel, 2025.

- Amstutz, L.J. Invasive Species; ABDO Publishing: North Mankato, MN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sapir-Hen, L.; Meiri, M.; Finkelstein, I. Iron Age pigs: New evidence on their origin and role in forming identity boundaries. Radiocarbon 2015, 57, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda, E. Are you being served? The responsiveness of public administration to citizens’ demands: An empirical examination in Israel. Public Adm. 2000, 78, 165–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling. 2012. Available online: https://imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/statswiki/FAQ/SobelTest?action=AttachFile&do=get&target=process.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Crawford, R. Signs and wayfinding in urban public spaces: The role of standardization in communication. Urban Des. Int. 2020, 25, 317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, A.; Sorensen, A.; Jacobsen, K. Do not feed the animals: The effectiveness of wildlife signage in shaping visitor behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 113964. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behavior: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, L.; Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A.; Bellert, A. Still “minding the gap” sixteen years later: Restorying pro-environmental behavior. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 34, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, O. “If you eat dogs, you’ll eat people”—Otherising on a Greek island in economic crisis. In The Anthropology of Fear—Cultures Beyond Emotions; Boscoboinik, A., Horakova, H., Eds.; LIT Verlag: Munster, Germany, 2014; pp. 69–84. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2p9bfn7s (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Asibey, M.O.; Yeboah, V.; Poku-Boansi, M.; Bamfo, C. Exploring the use, behaviour and role of urbanites towards management and sustainability of Kumasi Rattray Park, Ghana. J. Urban Manag. 2019, 8, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E.; Rizzo, F. Small projects/large changes: Participatory design as an open participated process. CoDesign 2011, 7, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S. Growing biodiverse urban futures: Renaturalization and rewilding as strategies to strengthen urban resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (female) | |||||||||||||

| 2. Age | −0.071 | ||||||||||||

| 3. Religion | 0.018 | 0.139 * | |||||||||||

| 4. Religiosity | −0.085 | 0.076 | −0.039 | ||||||||||

| 5. Residency in Nesher in years | 0.021 | 0.386 ** | 0.122 * | 0.090 | |||||||||

| 6. Marital status (married/in a relationship) | −0.026 | 0.114 | 0.050 | 0.025 | −0.036 | ||||||||

| 7. Children (under 18) | 0.097 | −0.317 ** | 0.030 | 0.017 | −0.169 ** | 0.260 ** | |||||||

| 8. Salary | −0.203 ** | 0.147 * | 0.163 ** | −0.018 | 0.099 | 0.286 ** | 0.148 * | ||||||

| 9. Voted for mayor | 0.001 | 0.065 | −0.002 | −0.027 | 0.092 | −0.073 | 0.007 | −0.014 | |||||

| 10. Political Ideology (right) | −0.129 * | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.297 ** | 0.059 | 0.016 | −0.001 | −0.075 | −0.079 | ||||

| 11. Perceived harm caused by human–animal interactions | 0.057 | −0.006 | 0.097 | 0.098 | 0.042 | −0.180 ** | −0.003 | 0.054 | −0.011 | −0.032 | |||

| 12. Support for Local Environmental Morality Policies | −0.039 | 0.148 * | 0.066 | 0.221 ** | 0.042 | 0.000 | −0.014 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.147 * | 0.342 ** | ||

| 13. Preference for biocentric (vs. anthropocentric) human–wildlife signage | −0.071 | −0.013 | −0.038 | −0.134 * | 0.153 ** | 0.201 ** | 0.067 | 0.146 * | −0.096 | −0.064 | −0.214 ** | −0.329 ** | |

| Mean | 0.58 | 47.41 | 0.95 | 3.34 | 22.70 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 2.83 | 1.28 | 4.58 | 1.91 | 5.20 | 1.77 |

| SD | 0.49 | 15.05 | 0.21 | 2.43 | 15.52 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 1.22 | 0.66 | 1.58 | 1.04 | 2.03 | 0.53 |

| Min | 0.00 | 18.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Max | 1.00 | 90.00 | 1.00 | 10.00 | 75.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 | 8.00 | 3.00 |

| Alpha Cronbach | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.56 |

| Dependent Variable = Preference for Biocentric (vs. Anthropocentric) Human–Wildlife Signage R2 = 0.172; F = 6.049 *** | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | β | T | ||||

| Constant | 1.944 | 9.469 *** | ||||

| Perceived harm caused by wild boars | −0.032 | −0.873 | ||||

| Support for local environmental morality policies | −0.078 | −4.810 *** | ||||

| Religiosity | −0.012 | −0.914 | ||||

| Gender (F) | −0.080 | −1.278 | ||||

| Marital status (married/in a relationship) | 0.167 | 2.379 * | ||||

| Children (under 18) | −0.002 | −0.037 | ||||

| Education | 0.009 | 0.925 | ||||

| Salary | 0.037 | 1.334 | ||||

| Voted for mayor | −0.003 | −0.069 | ||||

| Conditional indirect effect of perceived harm caused by wild boars on support for local environmental morality policies with simple slopes for political ideology (right) | ||||||

| Political ideology (right) | β | LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Left (liberal)-3 | −0.078 | −0.114 | −0.045 | |||

| Center-4 | −0.069 | −0.101 | −0.040 | |||

| Right (conservative)-6 | −0.050 | −0.080 | −0.026 | |||

| Index for moderated mediation: β = 0.009 * LLCI= 0.002; ULCI= 0.017 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beeri, I.; Segev, O. Anthropocentric or Biocentric? Socio-Cultural, Environmental, and Political Drivers of Urban Wildlife Signage Preferences and Sustainable Coexistence. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209231

Beeri I, Segev O. Anthropocentric or Biocentric? Socio-Cultural, Environmental, and Political Drivers of Urban Wildlife Signage Preferences and Sustainable Coexistence. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209231

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeeri, Itai, and Onna Segev. 2025. "Anthropocentric or Biocentric? Socio-Cultural, Environmental, and Political Drivers of Urban Wildlife Signage Preferences and Sustainable Coexistence" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209231

APA StyleBeeri, I., & Segev, O. (2025). Anthropocentric or Biocentric? Socio-Cultural, Environmental, and Political Drivers of Urban Wildlife Signage Preferences and Sustainable Coexistence. Sustainability, 17(20), 9231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209231