A Scale Development Study on Green Marketing Mix Practice Culture in Small and Medium Enterprises

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Gap in Literature and Purpose of Research

1.2. Limiting the Scope to 4Ps

1.3. The “People” Dimension as a Separate Field

1.4. Providing a Foundational Measurement Instrument

- It can offer detailed information about the status of SMEs regarding their GMMPC and assist in making assessments; it can also provide data for determining businesses’ green marketing strategies.

- It can enable comparative analyses among firms of different sizes operating in various industry sectors across different regions.

- It can play a supportive role in evaluating the effectiveness of green marketing practices and providing a scientific basis for research.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptualizing Green Marketing Mix Practice Culture

2.2. Green Marketing Orientation

2.3. Green Marketing Mix

2.3.1. Green Product

2.3.2. Green Price

2.3.3. Green Place/Distribution

2.3.4. Green Promotion

3. Method

4. Scale Development Study on Green Marketing Mix Practice Culture

4.1. Study 1

- Pre-test analysis

- Stages 1 & 2: Creation of the item pool and submission for expert review

- Stage 3: Calculation of Content Validity Ratios (CVR)

- NE = Number of experts rating the item as “Necessary”

- N = Total number of experts

- Stage 4:

4.2. Study 2

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Statements | Expert Opinions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Experts Who Said “Not Necessary” | Number of Experts Who Said “Should be Corrected | Number of Experts Who Said “Necessary” | ||

| 1 | We design products to save energy with reduced materials. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 2 | Choosing packaging materials from biodegradable products is effective in increasing the sales of the enterprise. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 3 | With the green packaging approach, our materials are less damaged (such as breakage, deterioration). | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 4 | The green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 5 | Green packaging practices make our products even lighter. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 6 | Green packaging practices reduce costs. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 7 | We use recycled materials in our products. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 8 | We consider environmental issues in distribution. | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 9 | We consider the environment when designing the product. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 10 | We use ecological green materials in production. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 11 | Our suppliers’ products are recyclable. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 12 | We advertise our green products. | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| 13 | We use renewable energy sources in production. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 14 | Our company offers innovative green products to the market. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 15 | Green products provide our company with the opportunity to differentiate. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 16 | The raw materials we use are safe for the environment. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 17 | We try to use less material in packaging. | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 18 | Our company produces environmentally friendly products. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 19 | Environment is the main criterion for supplier selection. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 20 | We support the green environmental components of the product. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 21 | A separate unit that monitors environmental costs has been established in our organization. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 22 | The use of recycled materials in the enterprise reduces costs. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 23 | Customers are willing to pay higher prices for green products. | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 24 | Our customers are willing to pay high prices for green products. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 25 | We take environmental factors into account in price policy. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 26 | We use local products to reduce transport costs. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 27 | Green packaging practices make our products lighter. | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 28 | We cover the additional cost of an environmentally friendly product. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 29 | We consider environmental issues in distribution. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 30 | We encourage the use of e-commerce as it is more environmentally friendly. | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 31 | The environmental damage of our distribution channel is minimized. | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| 32 | We use electronic information systems in green transport. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 33 | Thanks to green transport, we use less fuel. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 34 | Thanks to green transport, we can reduce costs by saving time on the delivery route. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 35 | We monitor emissions from the distribution of the product. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 36 | The environmental aspect of our products is at the forefront in marketing. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 37 | Our environmentally friendly practices are updated on our website. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 38 | Our company chooses packaging materials from degradable products. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 39 | The profit margin has increased because of material reduction in the provision of services. | 6 | 0 | 4 |

| 40 | Our business uses the environmentally friendly green label. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 41 | The labels contain information on recycling. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 42 | We prevent the use of dangerous substances in packaging. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 43 | The amount of goods is minimized to increase delivery flexibility. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 44 | The warehouse of our company is organizing environmentally friendly methods. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 45 | The use of environmentally friendly green labels is effective in increasing business sales. | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| 46 | We choose cleaner transport systems. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 47 | We use green arguments in marketing communication. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 48 | Our marketing communication reflects the company’s commitment to the environment. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 49 | Environmental claims in advertising are often met with criticism from the environment (competitors, consumer organizations, etc.). | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 50 | We support the green environmental components of the product. | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 51 | Environmental labelling is an effective promotional tool for our company. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 52 | We inform consumers about environmental management in the company. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 53 | We participate in sponsorship activities on environmental issues. | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 54 | We use specific environmental criteria for our suppliers. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 55 | We prevent the use of hazardous substances in the packaging of the product. | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| 56 | We implement paperless policies in our procurement as much as possible. | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 57 | We emphasize the image of “environmentally friendly business” in promotional activities. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 58 | Our company uses statements reflecting the reality of the product advertisements. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 59 | Our image as an environmentally friendly company gives us a competitive advantage. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 60 | We emphasize in our advertisements that our products are green. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 61 | The product packaging is colored green, which is identical to the environment. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 62 | Our product promotions include environmental protection activities. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 63 | We aim to minimize negative impacts on the environment throughout the product life cycle. | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| 64 | The use of Information Technologies in the enterprise reduces distribution costs. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 65 | We make sure that recycled materials are used in production. | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 66 | The production process in our enterprise is based on ISO 14001 certification. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 67 | Customers want the company to produce green products. | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| 68 | When promoting products, we prefer digital communication as it is more environmentally friendly. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 69 | It is normal for green products to be priced slightly higher than other products. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 70 | We use environmentally friendly technologies in the production process. | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 71 | We use recycled materials for packaging. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 72 | Our company tries to convince its customers to be environmentally conscious during direct sales. | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 73 | Our company tries to convince its customers to be environmentally sensitive during direct sales. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 74 | We utilize green vehicles in the distribution channel. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 75 | We can reduce our costs with green transport. | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| 76 | We design for remanufacturing so that waste can be recycled. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 77 | The enterprise uses minimal packaging materials. | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| 78 | We use integrated transport systems in distribution. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 79 | Our business is trying to reduce the use of packaging. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 80 | Producing green products increases costs. | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| 81 | The company co-operates with environmental groups to effectively promote a “green image”. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 82 | We minimize our waste in production. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

Appendix B

| No | Items | Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | We design products to save energy with reduced materials. | |

| 2 | We design for remanufacturing so that waste can be recycled. | |

| 3 | With the green packaging approach, our materials are less damaged (such as breakage, deterioration). | Green Packaging |

| 4 | The green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste. | Green Packaging |

| 5 | Green packaging practices make our products even lighter. | Green Packaging |

| 6 | Green packaging practices reduce costs. | |

| 7 | We use recycled materials in our products. | |

| 8 | We use recycled materials for packaging. | |

| 9 | We consider the environment when designing the product. | |

| 10 | We use ecological green materials in production. | |

| 11 | Our suppliers’ products are recyclable. | |

| 12 | We minimize our waste in production. | |

| 13 | We use renewable energy sources in production. | |

| 14 | Our company offers innovative green products to the market. | |

| 15 | Green products provide our company with the opportunity to differentiate. | |

| 16 | The raw materials we use are safe for the environment. | |

| 17 | The production process in our enterprise is based on ISO 14001 certification. | |

| 18 | Our company produces environmentally friendly products. | |

| 19 | Environment is a key criterion for supplier selection. | |

| 20 | We support the green environmental components of the product. | |

| 21 | A separate unit monitoring environmental costs has been established in our organization. | |

| 22 | The use of recycled materials in our business reduces costs. | |

| 23 | It is normal for green products to be priced slightly higher than other products. | |

| 24 | Our customers are willing to pay high prices for green products. | |

| 25 | We take environmental factors into account in our price policy. | |

| 26 | We use local products to reduce transportation costs. | |

| 27 | The use of Information Technologies in the enterprise reduces distribution costs. | |

| 28 | We cover the additional cost of a green product. | |

| 29 | We consider environmental issues in distribution. | |

| 30 | Our company tries to persuade its customers to be environmentally conscious during direct sales. | |

| 31 | We utilize green vehicles in the distribution channel. | Green Distribution |

| 32 | We use electronic information systems in green transportation. | |

| 33 | We use less fuel thanks to green transportation. | Green Distribution |

| 34 | Thanks to green transportation, we can reduce costs by saving time on the shipment route. | |

| 35 | We monitor emissions from the distribution of the product. | Green Distribution |

| 36 | The environmental aspect of our products is at the forefront in marketing. | |

| 37 | Our environmental practices are updated on our website. | |

| 38 | Our company chooses packaging materials from degradable products. | |

| 39 | Our business is trying to reduce the use of packaging. | |

| 40 | Our business uses environmentally friendly green labels. | |

| 41 | The labels contain information on recycling. | |

| 42 | We prevent the use of hazardous substances in packaging. | |

| 43 | The amount of handling of goods is minimized to increase delivery flexibility. | |

| 44 | The warehouse of our business is organized with environmentally friendly methods. | |

| 45 | We use integrated transportation systems in distribution. | |

| 46 | We choose cleaner transportation systems. | Green Distribution |

| 47 | We use green arguments in marketing communication. | |

| 48 | Our marketing communications reflect the company’s commitment to the environment. | |

| 49 | Environmental claims in advertising are often met with criticism from the environment (competitors, consumer organizations, etc.). | |

| 50 | The company cooperates with environmental groups to effectively promote a “green image”. | |

| 51 | Environmental labeling is an effective promotional tool for our company. | |

| 52 | We inform consumers about environmental management in the company. | Environmental Promotion |

| 53 | We participate in sponsorship activities on environmental issues. | Environmental Promotion |

| 54 | We use specific environmental criteria for our suppliers. | Environmental Promotion |

| 55 | When promoting our products, we prefer digital communication as it is more environmentally friendly. | |

| 56 | We implement paperless policies in our procurement as much as possible. | |

| 57 | We emphasize the image of environmentally friendly businesses in promotional activities. | Environmental Promotion |

| 58 | Our company uses factual statements in product advertisements. | |

| 59 | Our image as an environmentally friendly company gives us a competitive advantage. | |

| 60 | We emphasize in our advertisements that our products are green. | Environmental Promotion |

| 61 | Green, identical to the environment, dominates the product packaging. | |

| 62 | Our product promotions include environmental protection activities. |

References

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 1998; ISBN 978-0-86571-392-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pooja, T.; Sujata, A.S.A.K. Sustainability Marketing: A Literature Review From 2001–2022. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Holappa, P. Sustainable Marketing in Micro and Small Enterprises. Master’s Thesis, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Halme, M.; Korpela, M. Responsible Innovation Toward Sustainable Development in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Resource Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Gangwar, V.P.; Dash, G. Green Marketing Strategies, Environmental Attitude, and Green Buying Intention: A Multi-Group Analysis in an Emerging Economy Context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.-K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M. Green Marketing Orientation: Conceptualization, Scale Development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masocha, R. Green Marketing Practices: Green Branding, Advertisements and Labelling and Their Nexus with the performance of SMEs in South Africa. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2020, 16, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziriri, E.; Chinomona, E. Modeling the Influence of Relationship Marketing, Green Marketing and Innovative Marketing on the Business Performance of Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises (SMMES). J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2016, 8, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, B.J.; Soule, C.A.A. Green Demarketing in Advertisements: Comparing “Buy Green” and “Buy Less” Appeals in Product and Institutional Advertising Contexts. J. Advert. 2016, 45, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.A.; Mishra, A.S.; Tiamiyu, M.F. Application of GREEN Scale to Understanding US Consumer Response to Green Marketing Communications. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the World through GREEN-Tinted Glasses: Green Consumption Values and Responses to Environmentally Friendly Products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravcikova, D.; Krizanova, A.; Kliestikova, J.; Rypakova, M. Green Marketing as the Source of the Competitive Advantage of the Business. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A. Green Marketing and Perceived SME Profitability: The Meditating Effect of Green Purchase behaviour. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 33, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Martínez, E.; Matute, J. Green Marketing in B2B Organisations: An Empirical Analysis from the Natural-resource-based View of the Firm. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2013, 28, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Yang, C.-H. Applying a Multiple Criteria Decision-Making Approach to Establishing Green Marketing Audit Criteria. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyadat, A.A.; Almuhana, M.; Al-Bataineh, T. The Role of Green Marketing Strategies for a Competitive Edge: A Case Study about Analysis of Leading Green Companies in Jordan. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Dangwal, R.; Raina, S. Conceptualisation, Development and Validation of Green Marketing Orientation (GMO) of SMEs in India: A Case of Electric Sector. J. Glob. Responsib. 2014, 5, 312–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaite-Vaitone, N.; Skackauskiene, I.; Díaz-Meneses, G. Measuring Green Marketing: Scale Development and Validation. Energies 2022, 15, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Rosenberger, P.J. Reevaluating Green Marketing: A Strategic Approach. Bus. Horiz. 2001, 44, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.H.; Mehraj, D. Identifying the Factors of Internal Green Marketing: A Scale Development and Psychometric Evaluation approach. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 43, 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, B.; Dauda, M.; Sani, S.A. Green Marketing Strategy and Its Effect on the Performance of Small and Medium Business Enterprises (SMEs). Int. J. Account. Financ. Adm. Res. 2024, 1, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sathana, V.; Velnampy, T.; Rajumesh, S. The Effect of Competitive and Green Marketing Strategy on Development of SMEs. J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hart, S.L. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-Based Theories of Competitive Advantage: A Ten-Year Retrospective on the Resource-Based view. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afum, E.; Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Baah, C.; Asamoah, G.; Kusi, L.Y. Green Market Orientation, Green Value-Based Innovation, Green Reputation and Enterprise Social Performance of Ghanaian SMEs: The Role of Lean Management. J. Bus. Amp. Ind. Mark. 2023, 38, 2151–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green Marketing”: An Analysis of Definitions, Strategy Steps, and Tools through a Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckwitz, A. Toward a Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2002, 5, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.C. The Concept of Routines Twenty Years After Nelson and Winter (1982) A Review of the Literature. Camb. J. Econ. 2003, 29, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S.G. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-674-04143-1. [Google Scholar]

- Felin, T.; Foss, N.J. Organizational Routines and Capabilities: Historical Drift and a Course-Correction Toward Microfoundations. Scand. J. Manag. 2009, 25, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Organizational Culture: Can It Be a Source of Sustained Competitive Advantage? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Combining Institutional and Resource-Based Views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayworth, T.; Leidner, D. Organizational Culture as a Knowledge Resource. In Handbook on Knowledge Management 1: Knowledge Matters; Holsapple, C.W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 235–252. ISBN 978-3-540-24746-3. [Google Scholar]

- Donate, M.J.; Guadamillas, F. The Effect of Organizational Culture on Knowledge Management Practices and Innovation. Knowl. Process Manag. 2010, 17, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.K.; Choudhury, D.; Rao, K.S.V.G. Impact of Strategic and Tactical Green Marketing Orientation on SMEs Performance. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2019, 9, 1633–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, S.; Matarazzo, M. Linking Green Marketing and SMEs Performance: A Psychometric Meta-Analysis. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2025, 63, 1063–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A. Facing the Backlash: Green Marketing and Strategic Reorientation in the 1990s. J. Strateg. Mark. 2000, 8, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Towards Sustainability: The Third Age of Green Marketing. Mark. Rev. 2001, 2, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Kaur, G. Green Marketing: An Attitudinal and Behavioural Analysis of Indian Consumers. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2004, 5, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, A.; Bañegil, T.M. Green Marketing Philosophy: A Study of Spanish Firms with Ecolabels. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, K.; Batubara, H.M.; Rosalina, R.; Evanita, S.; Friyatmi, F. Effect of Green Marketing Mix on Purchase Intention: Moderating Role of Environmental Knowledge. J. Apresiasi Ekon. 2024, 12, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, T.O. Impact of Green Marketing Mix on Purchase Intention. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2018, 5, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Prabhakar, G.; Luo, X.; Tseng, H.-T. Exploring Generation Z Consumers’ Purchase Intention towards Green Products During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. e-Prime—Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 8, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jave-Chire, M.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Guevara-Zavaleta, V. Footwear Industry’s Journey through Green Marketing Mix, Brand Value and Sustainability. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdrolia, E.; Zarotiadis, G. A Comprehensive Review for Green Product Term: From Definition to Evaluation. J. Econ. Surv. 2019, 33, 150–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-H.; Lin, G.-Y.; Zheng, Y.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, P.-Z.; Su, Z.-C. Exploring the Effect of Starbucks’ Green Marketing on Consumers’ Purchase Decisions from Consumers’ Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.R.; da Costa, M.F.; Maciel, R.G.; Aguiar, E.C.; Wanderley, L.O. Consumer Antecedents towards Green Product Purchase Intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Reinventing Marketing to Manage the Environmental Imperative. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya, P.; Sivakoti Reddy, M. Analyzing the Effect of Product, Promotion and Decision Factors in Determining Green Purchase Intention: An Empirical Analysis. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustini, M.; Baloran, A.; Bagano, A.; Tan, A.; Athanasius, S.; Retnawati, B. Green Marketing Practices and Issues: A Comparative Study of Selected Firms in Indonesia and Philippines. J. Asia-Pac. Bus. 2021, 22, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, A.; Bandara, V.; Silva, A.; De Mel, D. Impact of Green Marketing Mix on Customers’ Green Purchasing Intention with Special Reference to Sri Lankan Supermarkets. South Asian J. Mark. 2020, 1, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Crane, A. Green Marketing: Legend, Myth, Farce or Prophesy? Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2005, 8, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthey, B.K. Impact of Green Marketing Practices on Consumer Purchase Intention and Buying Decision with Demographic Characteristics as Moderator. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2019, 6, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.K.; Garg, A.; Ram, S.; Gajpal, Y.; Zheng, C. Research Trends in Green Product for Environment: A Bibliometric Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukonza, C.; Swarts, I. The Influence of Green Marketing Strategies on Business Performance and Corporate Image in the Retail Sector. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer Banzhaf, H. Green Price Indices. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2005, 49, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E. Addressing Climate Change Through Price and Non-Price Interventions. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2019, 119, 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, N.A. “Greening” the Marketing mix: Do Firms Do It and Does it Pay Off? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Rethinking Marketing: Shifting to a Greener Paradigm. In Greener Marketing; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-1-351-28308-3. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo, A.; Arroyo, P.; Carrete, L. Do Environmental Practices of Enterprises Constitute an Authentic Green Marketing Strategy? A Case Study from Mexico. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davari, A.; Strutton, D. Marketing Mix Strategies for Closing the Gap Between Green Consumers’ Pro-Environmental Beliefs and Behaviors. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önem, Ş.; Selvi, M.S. Scale Development on the Effect of Social Media Influencers on Purchase Intention. MAKU IIBFD 2024, 11, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, B. The Impact of Green Marketing Mix Elements on Green Customer Based Brand Equity in an Emerging Market. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022, 15, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novela, S.; Novita; Hansopaheluwakan, S. Analysis of Green Marketing Mix Effect on Customer Satisfaction Using 7p Approach. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2018, 26, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Soelton, M.; Rohman, F.; Asih, D.; Saratian, E.T.P.; Wiguna, S.B. Green Marketing That Effect the Buying Intention Healthcare Products. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, S.O. Unveiling Willingness to Pay for Green Stadiums: Insights from a Choice Experiment. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Jiang, Z. Willingness to pay a premium price for green products: Does a Reference Group Matter? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 8699–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Wang, Y.; Hou, C.; Liu, B. Will the Public Pay for Green Products? Based on Analysis of the Influencing Factors for Chinese’s Public Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Green Products. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 61408–61422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelderman, C.J.; Schijns, J.; Lambrechts, W.; Vijgen, S. Green Marketing as an Environmental Practice: The Impact on Green Satisfaction and Green Loyalty in a Business-to-Business Context. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2061–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavar, T.; Kubeš, V.; Baran, D. Willingness to Pay for Eco-Friendly Furniture Based on Demographic Factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meet, R.K.; Kundu, N.; Ahluwalia, I.S. Does Socio Demographic, Green Washing, and Marketing Mix Factors Influence Gen Z Purchase Intention Towards Environmentally Friendly Packaged Drinks? Evidence from Emerging Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Seidu, A.S.; Tweneboah-Koduah, E.Y.; Ahmed, A.S. Green Marketing Mix and Repurchase Intention: The Role of Green Knowledge. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2024, 15, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yi, S. Pricing Policies of Green Supply Chain Considering Targeted Advertising and Product Green Degree in the Big Data Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, K.; Yavari, M. Pricing Policies for a Dual-Channel Green Supply Chain Under Demand Disruptions. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 127, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, P.J.; Uchida, T.; Conrad, J.M. Price Premiums for Eco-friendly Commodities: Are ‘Green’ Markets the Best Way to Protect Endangered Ecosystems? Environ. Resour. Econ 2005, 32, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J.A.; Stafford, E.R.; Hartman, C.L. Avoiding Green Marketing Myopia: Ways to Improve Consumer Appeal for Environmentally Preferable Products. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2006, 48, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Yang, J. Is Green Place-Based Policy Effective in Mitigating Pollution? Firm-Level Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 83, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Streimikiene, D.; Qadir, H.; Streimikis, J. Effect of Green Marketing Mix, Green Customer Value, and Attitude on Green Purchase Intention: Evidence from the USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 11473–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, T.; Ibrahim, S.; Hasaballah, A.H.; Bleady, A. The Influence of Green Marketing Mix on Purchase Intention: The Mediation Role of Environmental Knowledge. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2017, 8, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.; Akdemir, M.A.; Kara, A.U.; Sagbas, M.; Sahin, Y.; Topcuoglu, E. The Mediating Role of Green Innovation and Environmental Performance in the Effect of Green Transformational Leadership on Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Pu, X.; Li, Y. Green Manufacturing Strategy Considering Retailers’ Fairness Concerns. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavo, J.U.; Trento, L.R.; de Souza, M.; Pereira, G.M.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Borchardt, M.; Zvirtes, L. Green Marketing in Supermarkets: Conventional and digitized marketing Alternatives to Reduce Waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Majali, M.; Tarabieh, S. Effect of Internal Green Marketing Mix Elements on Customers’ Satisfaction in Jordan: Mu’tah University Students. Jordan J. Bus. Adm. 2020, 16, 411–434. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-López, L.E.; Álamo-Vera, F.R.; Ballesteros-Rodríguez, J.L.; De Saá-Pérez, P. Socialization of Business Students in Ethical Issues: The Role of Individuals’ Attitude and Institutional Factors. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, E.C.; Banterle, A.; Stranieri, S. Trust to Go Green: An Exploration of Consumer Intentions for Eco-Friendly Convenience Food. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 148, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, U.; Bentley, Y.; Pang, G. The role of collaboration in the UK Green Supply Chains: An Exploratory Study of the Perspectives of Suppliers, Logistics and Retailers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 70, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhou, Y.; Bian, J.; Lai, K.K. Optimal Channel Structure for a Green Supply Chain with Consumer Green-Awareness Demand. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 324, 601–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaysoy, O.; Topcuoglu, E.; Ozgen-Cigdemli, A.O.; Kaygin, E.; Kosa, G.; Turan-Torun, B.; Kobanoglu, M.S.; Uygungil-Erdogan, S. The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction in the Effect of Green Transformational Leadership on Intention to Leave the Job. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1490203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaibhav, R.; Bhalerao, V.; Deshmukh, A. Green Marketing: Greening the 4 Ps of Marketing. Int. J. Knowl. Res. Manag. E-Commer. 2015, 5, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.K.; Yazdanifard, R. The Concept of Green Marketing and Green Product Development on Consumer Buying Approach. Glob. J. Commer. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 3, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Arseculeratne, D.; Yazdanifard, R. How Green Marketing Can Create a Sustainable Competitive Advantage for a Business. Int. Bus. Res. 2013, 7, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbes, C.; Beuthner, C.; Ramme, I. How Green is Your Packaging—A Comparative International Study of Cues Consumers use to Recognize Environmentally Friendly Packaging. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Lei, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. The Influence of Green Packaging on Consumers’ Green Purchase Intention in the Context of Online-to-Offline Commerce. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2021, 23, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.S.; Bait Ali Sulaiman, M.A.; Hasan Al-Kumaim, N.; Mahmood, A.; Abbas, M. Green Marketing Approaches and Their Impact on Consumer Behavior towards the Environment—A Study from the UAE. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonysamy, K.; Paulraj, G. Examining the Effects of Green Attitude on the Purchase Intention of Sustainable Packaging. Sustain. Agri Food Environ. Res. Discontin. 2023, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; Choudhary, S.; Kumar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Khan, S.A.R.; Panda, T.K. Do Altruistic and Egoistic Values Influence Consumers’ Attitudes and Purchase Intentions Towards Eco-Friendly Packaged Products? An Empirical Investigation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Noh, J.; Oh, Y.; Park, K.-S. Structural Relationships of a Firm’s Green Strategies for Environmental Performance: The Roles of Green Supply Chain Management and Green Marketing Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.P. Consumers’ Purchase Behaviour and Green Marketing: A Synthesis, Review and Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.; Ali, N.A. The Impact of Green Marketing Strategy on the Firm’s Performance in Malaysia. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, W.; Xu, E.; Xu, X. Pricing and Green Promotion Decisions in a Retailer-Owned Dual-Channel Supply Chain with Multiple Manufacturers. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2023, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.S. Green Marketing Strategies: How Do They Influence Consumer-Based Brand Equity? J. Glob. Bus. Adv. 2017, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Rahman, M.d.S. Measuring the Impact of Green Marketing Mix on Green Purchasing Behavior: A Study on Bangladeshi Consumers. Comilla Univ. J. Bus. Stud. 2018, 5, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P. State of Green Marketing Research over 25 years (1990–2014): Literature Survey and Classification. Mark. Intell. Amp. Plan. 2016, 34, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-H.; Malek, K.; Roberts, K.R. The Effectiveness of green Advertising in the Convention Industry: An Application of a Dual Coding Approach and the Norm Activation Model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, K.C.; Nguyen-Viet, B.; Phuong, V.H.N. Toward Sustainable Development and Consumption: The Role of the Green Promotion Mix in Driving Green Brand Equity and Green Purchase Intention. J. Promot. Manag. 2023, 29, 824–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.; Gani, A.; Taufan, R.; Syahnur, H.; Basalamah, J. Green Marketing Practice In Purchasing Decision Home Care Product. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 893–896. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Su, W.; Hahn, J. How Green Transformational Leadership Affects Employee Individual Green Performance—A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, S.B.; Martínez, M.P.; Correa, C.M.; Moura-Leite, R.C.; Silva, D.D. Greenwashing Effect, Attitudes, and Beliefs in Green Consumption. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-T.; Niu, H.-J. Green Consumption: Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Consciousness, Social Norms, and Purchasing Behavior. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, S. “I Buy Green Products for my Benefits or Yours”: Understanding Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Green Products. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 34, 1721–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.; Woolley, M. Green Marketing Messages and Consumers’ Purchase Intentions: Promoting Personal Versus Environmental Benefits. J. Mark. Commun. 2014, 20, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F.-M.; Peattie, K. Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-119-96619-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen–Viet, B.; Nguyen Anh, T. Green Marketing Functions: The Drivers of Brand Equity Creation in Vietnam. J. Promot. Manag. 2022, 28, 1055–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Sha, Y.; Ji, H.; Fan, J. What Affect Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Green Packaging? Evidence from China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Masani, S.; Dasgupta, T. Packaging-Influenced-Purchase Decision Segment the Bottom of the Pyramid Consumer marketplace? Evidence from West Bengal, India. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2022, 27, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, R.; Altunışık, R.; Bayraktaroğlu, S.; Yıldırım, E. Research Methods in Social Sciences: SPSS Applications, 8th ed.; Sakarya Publishing: Sakarya, Türkiye, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, A.C.; Bush, R.F. Marketing Research; Pearson/Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-13-228035-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSTİM OSTİM Hakkında. Available online: https://www.ostim.org.tr/sizin-fabrikaniz-ostim (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Yazıcıoğlu, Y.; Erdoğan, S. SPSS Uygulamalı Bilimsel Araştırma Yöntemleri, 4th ed.; Detay Yayıncılık: Ankara, Türkiye, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sekeran, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, G.D. Determining Sample Size. Available online: https://www.gjimt.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2_Glenn-D.-Israel_Determining-Sample-Size.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. Ten Steps in Scale Development and Reporting: A Guide for Researchers. Commun. Methods Meas. 2018, 12, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeele, V.V.; Spiel, K.; Nacke, L.; Johnson, D.; Gerling, K. Development and Validation of the Player Experience Inventory: A Scale to Measure Player Experiences at the Level of Functional and Psychosocial Consequences. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2020, 135, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulard, J.; McGehee, N.; Knollenberg, W. Developing and Testing the Transformative Travel Experience Scale (TTES). J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 923–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önem, Ş.; Selvi, M.S. General Attitude Scale for Social Media Influencers. MMI 2024, 15, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A Quantitative Approach to Content Validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, C.; Scally, A.J. Critical Values for Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2014, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E.; Gyimóthy, S. Too afraid to Travel? Development of a Pandemic (COVID-19) Anxiety Travel Scale (PATS). Tour. Manag. 2021, 84, 104286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytras, M.D.; Visvizi, A.; Chopdar, P.K.; Sarirete, A.; Alhalabi, W. Information Management in Smart Cities: Turning End Users’ Views into Multi-Item Scale Development, Validation, and Policy-Making Recommendations. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.P.; Chatterjee, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Akter, S. Understanding Dark Side of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Integrated Business Analytics: Assessing firm’s Operational Inefficiency and Competitiveness. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2022, 31, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing Validity: New Developments in Creating Objective Measuring Instruments. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Cai, R.; Gursoy, D. Developing and Validating a Service Robot Integration Willingness Scale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, C.W.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-292-02190-4. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992; p. 442. ISBN 978-0-8058-1062-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck, R.; O’Dell, L.L. Applications of Standard Error Estimates in Unrestricted Factor Analysis: Significance Tests for Factor Loadings and Correlations. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Arizmendi, C.; Gates, K.M. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) Programs in R. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2019, 26, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.L. A Rationale and Test for the Number of Factors in Factor Analysis. Psychometrika 1965, 30, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.-J.; Cheng, C.-P. Parallel Analysis with Unidimensional Binary Data. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2005, 65, 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-321-05677-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Elo, S.; Pölkki, T.; Miettunen, J.; Kyngäs, H. Testing and Verifying Nursing Theory by Confirmatory Factor Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottem, E. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the WPPSI for Language-Impaired Children. Scand. J. Psychol. 2003, 44, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yaşlıoğlu, M.M. Factor Analysis and Validity in Social Sciences: Using Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses. J. Istanbul Univ. Fac. Bus. Adm. 2017, 46, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, T.A.; Worthington, R.L. Item Response Theory in Scale Development Research: A Critical Analysis. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 44, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, D.; Bozman, C.; McPherson, M.; Valente, F.; Zhang, A. Information Entropy and Scale Development. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 2021, 9, 1183–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Miles, J.N.V.; Davies, M.N.O.; Walker, S. Coefficient alpha: A Useful Indicator of Reliability? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2000, 28, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuhadar, I.; Yang, Y.; Paek, I. Consequences of Ignoring Guessing Effects on Measurement Invariance Analysis. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 2021, 45, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akude, D.N.; Akuma, J.K.; Kwaning, E.A.; Asiama, K.A. Green Marketing Practices and Sustainability Performance of Manufacturing Firms: Evidence from Emerging Markets. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2025, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-P.; Lee, L.; Chou, C.J. Correlations among Product Development, Product Innovation, and Green Marketing in Healthcare Industry. RCIS 2024, 85, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.-H.; Song, J. Effect of Eco-friendly Management of Golf Clubs on Golfers’ Behavioral Intention to Return: Green Image, Perceived Quality as Meditator and Green Marketing as Moderator 2025. Available online: https://sciety.org/articles/activity/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5906138/v1?utm_source=sciety_labs_article_page (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Szabo, S.; Webster, J. Perceived Greenwashing: The Effects of Green Marketing on Environmental and Product Perceptions. J Bus Ethics 2021, 171, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. A ‘Business Opportunity’ Model of Corporate Social Responsibility for Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Representative Item (Translated from the Original Pool) | Primary Literature Sources for Item Generation |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Promotion | “We emphasize the “eco-friendly business” image in our promotional activities.” | Grounded in the communication of environmental efforts and credibility. Key concepts were derived from the works on green advertising, brand image, and sponsorships [6,77,106,112]. |

| Green Packaging | “The green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste.” | Based on the product-centric dimension of the green marketing mix, focusing on tangible actions like material reduction, recyclability, and dematerialization (lighter products) [21,27,97,124]. |

| Green Distribution | “We select cleaner transportation systems to reduce our environmental impact.” | Stems from the “place” element of the marketing mix, focusing on logistics and supply chain. Items were inspired by literature on reducing the carbon footprint through cleaner transport, fuel efficiency, and emission monitoring [6,27,79]. |

| Panel Size | Proportion Agreeing Essential | CVR Critical Exact Values | One-Sided p Value | N Critical (Min. No. of Experts Required to Agree Item Essential) | N Critically Calculated from the CRITBINOM Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.031 | 5 | 4 |

| 6 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.016 | 6 | 5 |

| 7 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.008 | 7 | 6 |

| 8 | 0.875 | 0.750 | 0.035 | 7 | 6 |

| 9 | 0.889 | 0.778 | 0.020 | 8 | 7 |

| 10 | 0.900 | 0.800 | 0.011 | 9 | 8 |

| 15 | 0.800 | 0.600 | 0.018 | 12 | 11 |

| 20 | 0.750 | 0.500 | 0.021 | 15 | 14 |

| 25 | 0.720 | 0.440 | 0.022 | 18 | 17 |

| 30 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.049 | 20 | 19 |

| Item No | NE | CVR | Comment | Item No | NE | CVR | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 42 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 2 | 1 | −0.80 | Eliminated | 43 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 3 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 44 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 4 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 45 | 6 | 0.20 | Eliminated |

| 5 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 46 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 6 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 47 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 7 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 48 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 8 | 2 | −0.60 | Eliminated | 49 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 9 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 50 | 8 | 0.60 | Eliminated |

| 10 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 51 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 11 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 52 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 12 | 7 | 0.40 | Eliminated | 53 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 13 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 54 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 14 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 55 | 4 | −0.20 | Eliminated |

| 15 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 56 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 16 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 57 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 17 | 8 | 0.60 | Eliminated | 58 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 18 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 59 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 19 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 60 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 20 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 61 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 21 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 62 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 22 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 63 | 7 | 0.40 | Eliminated |

| 23 | 5 | 0,00 | Eliminated | 64 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 24 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 65 | 8 | 0.60 | Eliminated |

| 25 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 66 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 26 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 67 | 4 | −0.20 | Eliminated |

| 27 | 8 | 0.60 | Eliminated | 68 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 28 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 69 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 29 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 70 | 5 | 0.00 | Eliminated |

| 30 | 8 | 0.60 | Eliminated | 71 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 31 | 7 | 0.40 | Eliminated | 72 | 5 | 0.00 | Eliminated |

| 32 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 73 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 33 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 74 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 34 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 75 | 6 | 0.20 | Eliminated |

| 35 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 76 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 36 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained | 77 | 2 | −0.60 | Eliminated |

| 37 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 78 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 38 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 79 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained |

| 39 | 4 | −0.20 | Eliminated | 80 | 7 | 0.40 | Eliminated |

| 40 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 81 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| 41 | 10 | 1.00 | Remained | 82 | 9 | 0.80 | Remained |

| Variable | Group | n | % | Variable | Group | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 53 | 33.33 | Experience | Less than 5 years | 23 | 14.50 |

| Male | 106 | 66.67 | 6–10 years | 55 | 34.60 | ||

| Age | 30 and below | 43 | 27.00 | 11–15 years | 38 | 23.90 | |

| 31–40 years | 37 | 23.30 | 16–20 years | 22 | 13.80 | ||

| 41–50 years | 48 | 30.20 | 21 years and above | 21 | 13.20 | ||

| 51 and above | 31 | 19.50 | Position | Lower level manager | 39 | 24.50 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 92 | 57.90 | Middle manager | 61 | 38.40 | |

| Single | 67 | 42.10 | Senior executive | 45 | 28.30 | ||

| Educational Level | High school and below | 21 | 13.20 | Boss (business owner) | 14 | 9.80 | |

| Associate degree | 34 | 21.40 | |||||

| Undergraduate | 71 | 44.60 | |||||

| Postgraduate | 33 | 20.80 | |||||

| Scale | Kolmogorov–Smirnov | Central Tendency Measurements | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Mean | Median | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| GMMPC | 0.101 | 159 | 0.000 | 3.417 | 3.583 | −0.727 | 0.539 |

| Statements | Factor Load Value (SPSS) | Cron. Alfa (α) | Parallel Analysis Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ncases: 159; Nvar: 12; Ndataset: 100; Percent: 95; Brian Oc) | |||||

| Raw Data | Means | Percently | |||

| Dimension 1 | α = 0.869 | 6.147 | 1.473 | 1.584 | |

| % of Variance: 46.564; Eigenvalue: 6.147 | |||||

| GMMPC 52 | 0.730 | ||||

| GMMPC 53 | 0.760 | ||||

| GMMPC 54 | 0.820 | ||||

| GMMPC 57 | 0.645 | ||||

| GMMPC 60 | 0.601 | ||||

| Dimension 2 | α = 0.854 | 1.419 | 1.352 | 1.419 | |

| % Of Variance: 8940; Eigenvalue: 1419 | |||||

| GMMPC 3 | −0.666 | ||||

| GMMPC 4 | −0.982 | ||||

| GMMPC 5 | −0.704 | ||||

| Dimension 3 | α = 0.842 | 1.347 | 1.254 | 1.320 | |

| % Of Variance: 5325; Eigenvalue: 1347 | |||||

| GMMPC 31 | 0.764 | ||||

| GMMPC 33 | 0.815 | ||||

| GMMPC 35 | 0.608 | ||||

| GMMPC 46 | 0.510 | ||||

| No | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GMMPC 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | GMMPC 4 | 0.701 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | GMMPC 5 | 0.579 ** | 0.702 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | GMMPC 31 | 0.407 ** | 0.350 ** | 0.379 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 5 | GMMPC 33 | 0.326 ** | 0.420 ** | 0.340 ** | 0.637 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 6 | GMMPC 35 | 0.440 ** | 0.402 ** | 0.317 ** | 0.529 ** | 0.558 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 7 | GMMPC 46 | 0.466 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.560 ** | 0.623 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 8 | GMMPC 52 | 0.319 ** | 0.384 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.349 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.400 ** | 0.450 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 9 | GMMPC 53 | 0.445 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.344 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.530 ** | 0.560 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 10 | GMMPC 54 | 0.396 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.433 ** | 0.414 ** | 0.461 ** | 0.472 ** | 0.583 ** | 0.600 ** | 0.672 ** | 1 | |||||

| 11 | GMMPC 57 | 0.399 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.494 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.416 ** | 0.459 ** | 0.460 ** | 0.519 ** | 0.490 ** | 0.608 ** | 1 | ||||

| 12 | GMMPC 60 | 0.451 ** | 0.415 ** | 0.490 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.425 ** | 0.483 ** | 0.528 ** | 0.484 ** | 0.557 ** | 0.582 ** | 0.626 ** | 1 | |||

| 13 | GMMPC 1st dimension | 0.872 ** | 0.909 ** | 0.858 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.411 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.426 ** | 0.476 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.514 ** | 1 | ||

| 14 | GMMPC 2nd dimension | 0.499 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.812 ** | 0.830 ** | 0.827 ** | 0.824 ** | 0.463 ** | 0.566 ** | 0.587 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.575 ** | 0.537 ** | 1 | |

| 15 | GMMPC 3rd dimension | 0.495 ** | 0.492 ** | 0.525 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.567 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.787 ** | 0.812 ** | 0.856 ** | 0.798 ** | 0.795 ** | 0.573 ** | 0.667 ** | 1 |

| 16 | GMMPC | 0.694 ** | 0.700 ** | 0.675 ** | 0.680 ** | 0.682 ** | 0.722 ** | 0.763 ** | 0.674 ** | 0.731 ** | 0.775 ** | 0.729 ** | 0.753 ** | 0.784 ** | 0.865 ** | 0.904 ** |

| X2(df) | p | RMSEA | CFI | GFI | SRMR | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.468 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.977 | 0.930 | 0.028 | 0.589 | 0.967 |

| Scale and Sub-Dimensions | Kolmogorov–Smirnov | Central Tendency Measurements | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Mean | Median | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| GMMPC | 0.083 | 387 | 0.000 | 3.461 | 3.583 | −0.512 | 0.026 |

| Items | Factor Load Value (SPSS) | Cron. Alfa (α) | PA Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ncases: 387; Nvar: 12; Ndataset: 100; Percent: 95; Brian Oc) | ||||||

| Raw Data | Means | Percently | ||||

| 1st Dimension | α = 0.855 | 6.132 | 1.297 | 1.346 | ||

| % of Variance: 47,755; Eigenvalue: 6132 | ||||||

| GMMPC 52 | We inform consumers about environmental management within our company. | 0.819 | ||||

| GMMPC 53 | We participate in sponsorship activities related to environmental issues. | 0.726 | ||||

| GMMPC 54 | We utilize specific environmental criteria for our suppliers. | 0.847 | ||||

| GMMPC 57 | We emphasize the “eco-friendly business” image in our promotional activities. | 0.648 | ||||

| GMMPC 60 | We highlight that our products are green in our advertisements. | 0.491 | ||||

| 2nd Dimension | α = 0.858 | 1.334 | 1.217 | 1.265 | ||

| % Of Variance: 8450; Eigenvalue: 1334 | ||||||

| GMMPC 3 | Our materials sustain less damage (such as breakage, spoilage) due to our green packaging approach. | −0.793 | ||||

| GMMPC 4 | The green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste. | −0.946 | ||||

| GMMPC 5 | Green packaging practices make our products even lighter. | −0.690 | ||||

| 3rd Dimension | α = 0.876 | 1.208 | 1.158 | 1.200 | ||

| % Of Variance: 6437; Eigenvalue: 1208 | ||||||

| GMMPC 31 | We utilize green vehicles in our distribution channel. | 0.863 | ||||

| GMMPC 33 | We use less fuel thanks to green transportation. | 0.847 | ||||

| GMMPC 35 | We monitor emissions resulting from product distribution. | 0.611 | ||||

| GMMPC 46 | We select cleaner transportation systems. | 0.543 | ||||

| X2(df) | p | RMSEA | CFI | GFI | SRMR | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

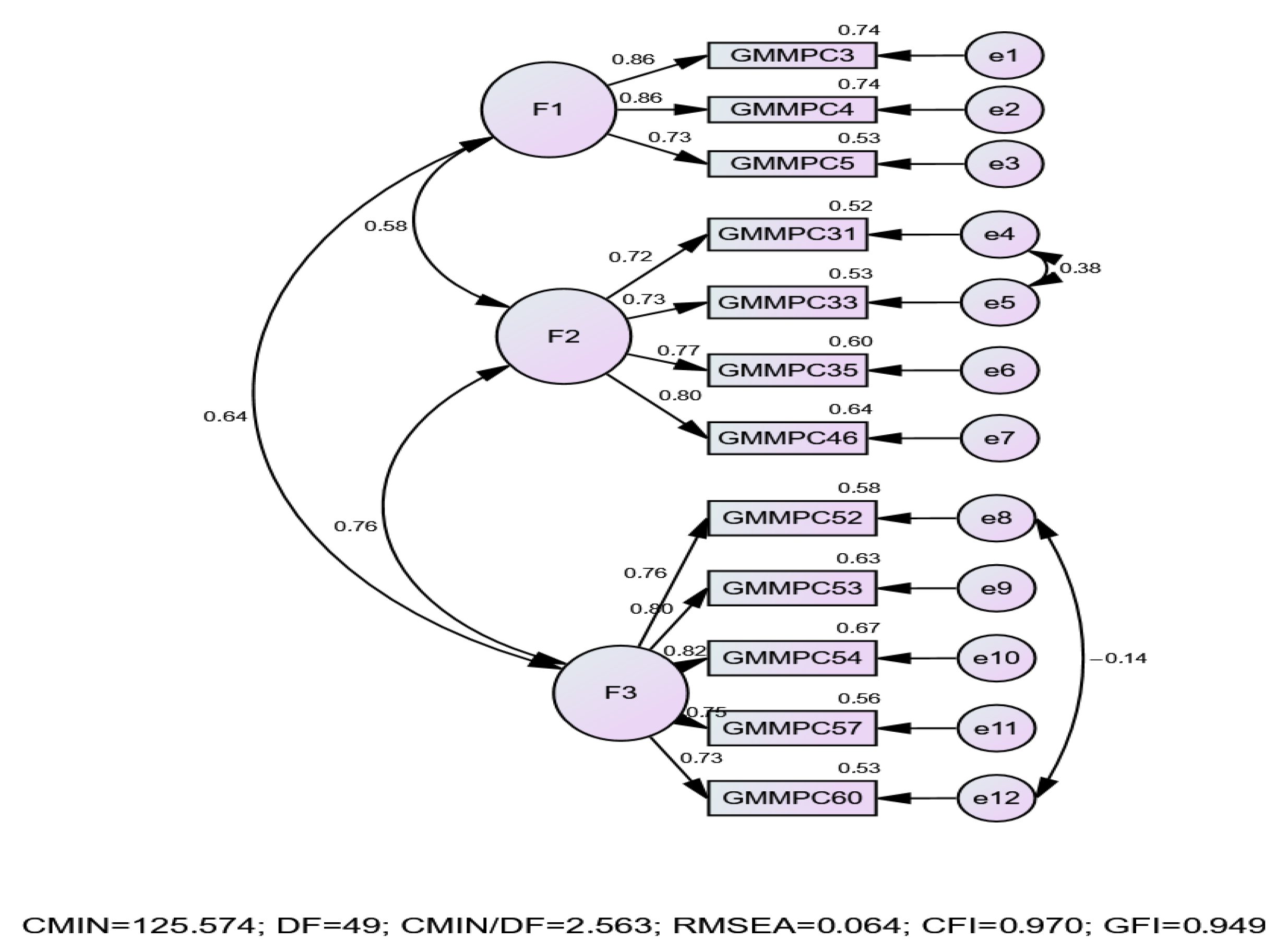

| 2.563 | 0.000 | 0.064 | 0.970 | 0.949 | 0.037 | 0.605 | 0.970 |

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMMPC 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| GMMPC 4 | 0.743 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| GMMPC 5 | 0.603 ** | 0.641 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| GMMPC 31 | 0.390 ** | 0.324 ** | 0.346 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| GMMPC 33 | 0.352 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.297 ** | 0.704 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| GMMPC 35 | 0.419 ** | 0.358 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.589 ** | 0.573 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| GMMPC 46 | 0.426 ** | 0.372 ** | 0.327 ** | 0.562 ** | 0.586 ** | 0.601 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| GMMPC 52 | 0.369 ** | 0.384 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.406 ** | 0.463 ** | 1 | |||||||

| GMMPC 53 | 0.468 ** | 0.375 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.455 ** | 0.442 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.547 ** | 0.599 ** | 1 | ||||||

| GMMPC 54 | 0.464 ** | 0.436 ** | 0.427 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.395 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.509 ** | 0.641 ** | 0.682 ** | 1 | |||||

| GMMPC 57 | 0.430 ** | 0.420 ** | 0.434 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.412 ** | 0.432 ** | 0.413 ** | 0.599 ** | 0.530 ** | 0.635 ** | 1 | ||||

| GMMPC 60 | 0.463 ** | 0.378 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.468 ** | 0.433 ** | 0.494 ** | 0.529 ** | 0.493 ** | 0.585 ** | 0.540 ** | 0.551 ** | 1 | |||

| GMMPC 1st dimension | 0.894 ** | 0.903 ** | 0.844 ** | 0.402 ** | 0.385 ** | 0.406 ** | 0.427 ** | 0.415 ** | 0.449 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.486 ** | 0.482 ** | 1 | ||

| GMMPC 2nd dimension | 0.474 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.853 ** | 0.851 ** | 0.831 ** | 0.815 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.581 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.574 ** | 0.483 ** | 1 | |

| GMMPC 3rd. dimension | 0.535 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.500 ** | 0.493 ** | 0.553 ** | 0.600 ** | 0.820 ** | 0.829 ** | 0.855 ** | 0.815 ** | 0.768 ** | 0.570 ** | 0.640 ** | 1 |

| GMMPC | 0.713 ** | 0.672 ** | 0.634 ** | 0.696 ** | 0.687 ** | 0.715 ** | 0.738 ** | 0.702 ** | 0.764 ** | 0.767 ** | 0.736 ** | 0.742 ** | 0.765 ** | 0.846 ** | 0.907 ** |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | SRMR | CFI | RMSEA | ∆χ2 | ∆df | ∆CFI | p-Value for ∆χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group1 | 71.927 | 49 | 1.468 | 0.028 | 0.977 | 0.054 | - | - | - | |

| Group2 | 125.574 | 49 | 2.563 | 0.037 | 0.970 | 0.064 | - | - | - | |

| Model 1: Configural | 197.501 | 98 | 2.015 | 0.037 | 0.972 | 0.043 | - | - | - | |

| Model 2: Weak (Metric) | 202.34 | 107 | 1.891 | 0.036 | 0.973 | 0.04 | 4.839 | 9 | 0.001 | 0.024 |

| Model 3: Scalar | 204.106 | 113 | 1.806 | 0.036 | 0.975 | 0.038 | 1.766 | 6 | 0.002 | 0.009 |

| Model 4: Strong | 214.827 | 127 | 1.692 | 0.037 | 0.976 | 0.036 | 10.721 | 14 | 0.001 | 0.050 |

| Model 5: Partial (GMMPC 3 − a1) | 198.481 | 99 | 2.005 | 0.037 | 0.972 | 0.043 | 16.346 | 28 | 0.004 | 0.082 |

| Factors (Sub-Dimensions) | GMMPC Scale Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Dimension: Environmental Promotion | We inform consumers about the environmental management within our company. | 0.819 |

| We participate in sponsorship activities related to environmental issues. | 0.726 | |

| We use specific environmental criteria for our suppliers. | 0.847 | |

| We emphasize the “eco-friendly business” image in our promotional activities. | 0.648 | |

| We highlight that our products are green in our advertisements. | 0.491 | |

| 2nd Dimension: Green Packaging | Our materials sustain less damage (such as breakage, spoilage) due to our green packaging approach. | 0.793 |

| The green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste. | 0.946 | |

| Green packaging practices make our products even lighter. | 0.690 | |

| 3rd Dimension: Green Distribution | We utilize green vehicles in our distribution channel. | 0.863 |

| We use less fuel thanks to green transportation. | 0.847 | |

| We monitor emissions resulting from product distribution. | 0.611 | |

| We select cleaner transportation systems. | 0.543 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özgün-Ayar, C.; Selvi, M.S. A Scale Development Study on Green Marketing Mix Practice Culture in Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6936. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156936

Özgün-Ayar C, Selvi MS. A Scale Development Study on Green Marketing Mix Practice Culture in Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6936. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156936

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzgün-Ayar, Candan, and Murat Selim Selvi. 2025. "A Scale Development Study on Green Marketing Mix Practice Culture in Small and Medium Enterprises" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6936. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156936

APA StyleÖzgün-Ayar, C., & Selvi, M. S. (2025). A Scale Development Study on Green Marketing Mix Practice Culture in Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability, 17(15), 6936. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156936