How Directors with Green Backgrounds Drive Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from China

Abstract

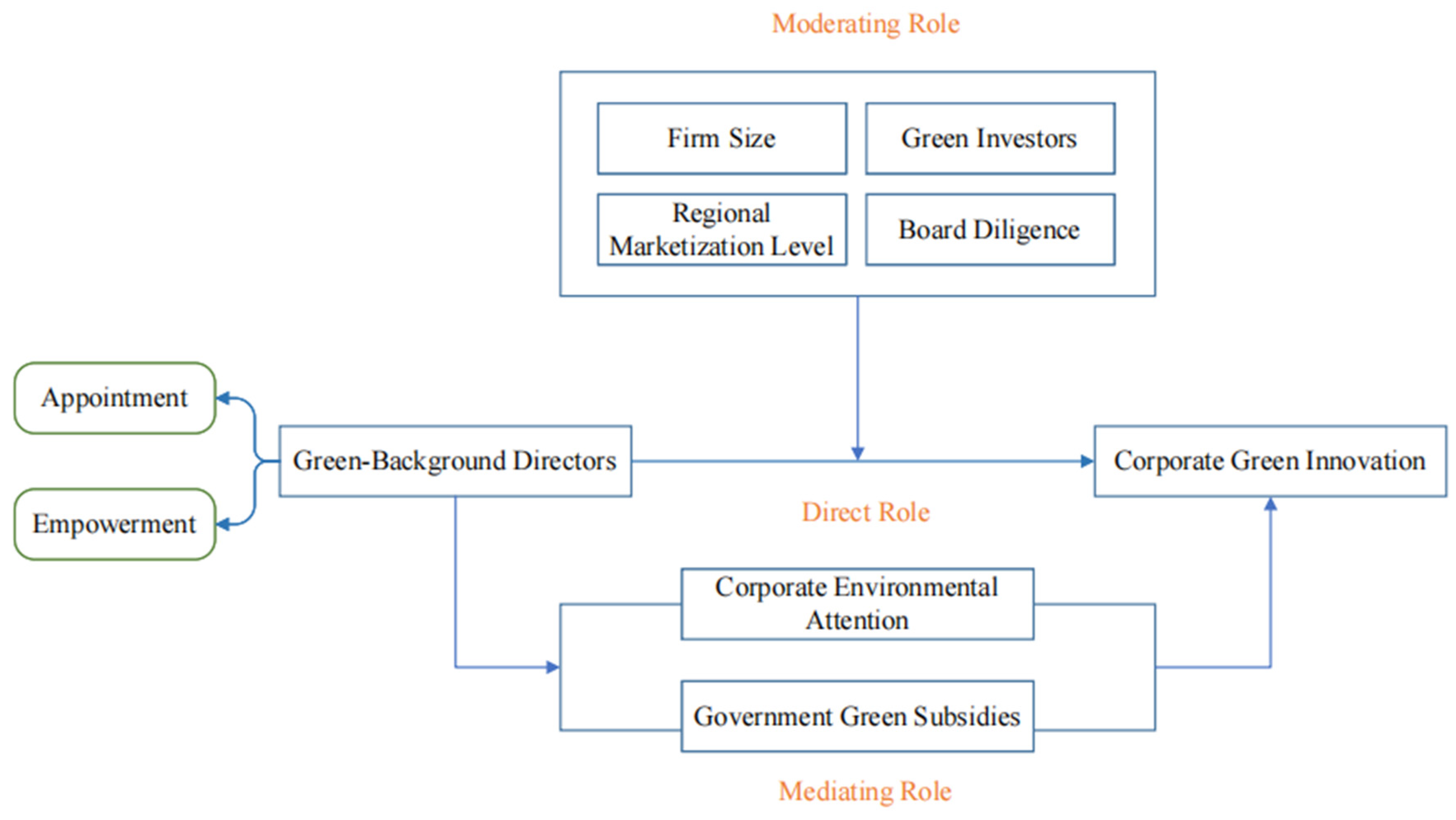

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. The Impact of Green Innovation on Enterprise Performance

2.1.2. The Influencing Factors of Corporate Green Innovation

2.1.3. The Impact of Managers’ Characteristics on Enterprise Performance

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Main Effect: Green-Background Directors and Corporate Green Innovation

2.2.2. Moderating Effects Analysis

2.2.3. Mediating Effects Analysis

3. Methodology

3.1. Variable Descriptions and Sample Selection

3.1.1. Dependent Variable

3.1.2. Independent Variables

3.1.3. Moderating Variables

3.1.4. Mediating Variables

3.1.5. Control Variables

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Models

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.2. Basic Results Analysis

4.2.1. The Influence of the Appointment of Green-Background Directors on the Corporate Green Innovation

4.2.2. The Influence of the Power of Green-Background Directors on Corporate Green Innovation

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Changing the Measurement of Green-Background Directors and Their Power

4.3.2. Changing the Measurement of Corporate Green Innovation

4.3.3. Changing the Regression Model

4.3.4. Relieving Endogenous Factors

4.4. Moderating Effect Test

4.4.1. Moderating Effect of Firm Size

4.4.2. Moderating Effect of Local Marketization Level

4.4.3. Moderating Effect of Board Diligence

4.4.4. Moderating Effect of Green Investors

4.5. Mediating Effect Test

4.5.1. Mediating Effect of Corporate Environmental Attention

4.5.2. Mediating Effect of Government Green Subsidies

4.6. Further Discussions

4.6.1. The Influence of Green-Background Directors on the Quality of Corporate Green Innovation

4.6.2. The Influence Continuity of Green-Background Directors on Corporate Green Innovation

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Tilcsik, A. Imprinting: Toward a Multilevel Theory. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 195–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snihur, Y.; Zott, C. The Genesis and Metamorphosis of Novelty Imprints: How Business Model Innovation Emerges in Young Ventures. AMJ 2020, 63, 554–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dass, N.; Kini, O.; Nanda, V.; Onal, B.; Wang, J. Board Expertise: Do Directors from Related Industries Help Bridge the Information Gap? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2014, 27, 1533–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiederig, T.; Tietze, F.; Herstatt, C. Green Innovation in Technology and Innovation Management—An Exploratory Literature Review. RD Manag. 2012, 42, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Jiang, P.; Murshed, M.; Shehzad, K.; Akram, R.; Cui, L.; Khan, Z. Modelling the Dynamic Linkages between Eco-Innovation, Urbanization, Economic Growth and Ecological Footprints for G7 Countries: Does Financial Globalization Matter? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J. Determinants of Environmental Innovation—New Evidence from German Panel Data Sources. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 63, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Wan, H.; Jiang, D. Financial Agglomeration and Regional Green Innovation Efficiency from the Perspective of Spatial Spillover. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The Influence of Green Innovation Performance on Corporate Advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M. The Effect of Environmental Regulation on Firms’ Competitive Performance: The Case of the Building & Construction Sector in Some EU Regions. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Lin, F. Does Global Diversification Promote or Hinder Green Innovation? Evidence from Chinese Multinational Corporations. Technovation 2024, 129, 102905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Belgacem, S.b.e.n.; Najam, H.; Abbas, J. Role of Environmental Regulations, Green Finance, and Investment in Green Technologies in Green Total Factor Productivity: Empirical Evidence from Asian Region. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qi, S.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X. Green Credit Policy, Government Behavior and Green Innovation Quality of Enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable Business Model Innovation: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; He, P. Can Public Participation Constraints Promote Green Technological Innovation of Chinese Enterprises? The Moderating Role of Government Environmental Regulatory Enforcement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Wu, Z.; Xu, J.; Shan, B. Environmental Justice and Green Innovation: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the Establishment of Environmental Courts in China. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 205, 107700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Shen, N.; Ying, H.; Wang, Q. Can Environmental Regulation Directly Promote Green Innovation Behavior?—— Based on Situation of Industrial Agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Qi, S.; Chen, Y. Using Green Technology for a Better Tomorrow: How Enterprises and Government Utilize the Carbon Trading System and Incentive Policies. China Econ. Rev. 2023, 78, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Yu, Y.; Du, K.; Zhang, N. How Does Environmental Regulation Promote Green Technology Innovation? Evidence from China’s Total Emission Control Policy. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 219, 108137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, M.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, B. Voluntary Environmental Regulation and Firm Innovation in China. Econ. Model. 2020, 89, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Chen, X.; Yi, N.; Zhang, L.; Li, D. Does Institutional Pressure Foster Corporate Green Innovation? Evidence from China’s Top 100 Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Nakaishi, T.; Kagawa, S. Neighbor’s Profit or Neighbor’s Beggar? Evidence from China’s Low Carbon Cities Pilot Scheme on Green Development. Energ. Polic. 2024, 195, 114318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Z.; He, Y.; Hao, Y. How Does the Green Credit Policy Affect the Technological Innovation of Enterprises? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2022, 113, 106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y. Does Environmental Regulation Spur Innovation? Quasi-Natural Experiment in China. World Dev. 2023, 168, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, M.D.; Bennedsen, M. Corporate Governance and Green Innovation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2016, 75, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the Mother of “green” Inventions: Institutional Pressures and Environmental Innovations. Strategy Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, S.; Lanoie, P. Does It Pay to Be Green? A Systematic Overview. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2008, 22, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkebsee, R.; Habib, A.; Li, J. Green Innovation and the Cost of Equity: Evidence from China. China Account. Financ. Rev. 2023, 25, 368–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xing, C.; Wang, Y. Does Green Innovation Mitigate Financing Constraints? Evidence from China’s Private Enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennings, K. Redefining Innovation—Eco-Innovation Research and the Contribution from Ecological Economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; He, F. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Performance and Green Innovation: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 48, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Qiao, F.; He, Y. Strategic Deviation and Corporate Green Innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 54, 103806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Bai, Y. Strategic or Substantive Innovation?—The Impact of Institutional Investors’ Site Visits on Green Innovation Evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, B.; Tian, X. Political Connections and Green Innovation: The Role of a Corporate Entrepreneurship Strategy in State-Owned Enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Z. Green Process Innovation, Green Product Innovation and Its Economic Performance Improvement Paths: A Survey and Structural Model. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Latan, H.; Sohal, A.S. Stakeholder Pressure, Green Innovation, and Performance in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: The Role of Green Dynamic Capabilities. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, B.; Fu, Q.; Tang, W.; Fatima, T. Impact of CEOs’ Environmental Experience on Corporate Green Innovation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 3290–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, W. The Role of Interlocking Directorates and Managerial Characteristics on Corporate Green Innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 74, 106818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Zhang, X. The Driving Path of Green Entrepreneurial Orientation from a Configuration Perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 380, 125064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Zhu, R.; Ye, Q. Managers’ Overconfidence, Institutional Investors’ Shareholding, and Corporate ESG Performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 72, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L. Senior management’s academic experience and corporate green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Zhao, Z. Overseas Exposures, Global Events, and Mutual Fund Performance. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 91, 848–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Wang, F.; Usman, M.; Ali Gull, A.; Uz Zaman, Q. Female CEOs and Green Innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Drivers of Green Innovations: The Impact of Export Intensity, Women Leaders, and Absorptive Capacity. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, M.C.; Fitza, M.A. Do board chairs matter? The influence of board chairs on firm performance. Strategy Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, O.; Ioannou, I. Mind the Gap: The Interplay Between External and Internal Actions in the Case of Corporate Social Responsibility. Strategy Manag. J. 2016, 37, 2569–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, J.L.; Berrone, P. The Power of One to Make a Difference: How Informal and Formal CEO Power Affect Environmental Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Montes-Sancho, M.J. An Institutional Perspective on the Diffusion of International Management System Standards: The Case of the Environmental Management Standard ISO 14001. Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.B.; Hermalin, B.E.; Weisbach, M.S. The Role of Boards of Directors in Corporate Governance: A Conceptual Framework and Survey. J. Econ. Lit. 2010, 48, 58–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S. Power in Top Management Teams: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 505–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyck, A.; Lins, K.V.; Roth, L.; Wagner, H.F. Do Institutional Investors Drive Corporate Social Responsibility? J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 131, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N. Green Innovation and Financial Performance: An Institutional Approach. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strategy Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. Do Environmental Management Systems Improve Business Performance in an International Setting? J. Int. Manag. 2008, 14, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Vafeas, N. Board Meeting Frequency and Firm Performance. J. Financ. Econ. 1999, 53, 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureli, S.; Del Baldo, M.; Lombardi, R.; Nappo, F. Nonfinancial Reporting Regulation and Challenges in Sustainability Disclosure and Corporate Governance Practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2392–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pástor, Ľ.; Stambaugh, R.F.; Taylor, L.A. Sustainable Investing in Equilibrium. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 550–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. The Price of Sin: The Effects of Social Norms on Markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Starks, L.T. Corporate Governance Proposals and Shareholder Activism: The Role of Institutional Investors. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 57, 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an Attention-Based View of the Firm. Strategy Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Vredenburg, H. Proactive Corporate Environmental Strategy and the Development of Competitively Valuable Organizational Capabilities. Strategy Manag. J. 1998, 19, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why Companies Go Green: A Model of Ecological Responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinski, N.; Bansal, P. Short on Time: Intertemporal Tensions in Business Sustainability. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Van Reenen, J.; Zingales, L. Innovation and Institutional Ownership. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm: Fifteen Years After. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate Green Bonds. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 142, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechezleprêtre, A.; Neumayer, E.; Perkins, R. Environmental regulation and the cross-border diffusion of new technology: Evidence from automobile patents. Res. Polic. 2015, 44, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G.; Xu, A.; Zhu, Y. Substantive green innovation or symbolic green innovation? The impact of ER on enterprise green innovation based on the dual moderating effects. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wei, J. Does CEOs’ Green Experience Affect Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility? Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 79, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.; Turkiela, J. The Powers That Be: Concentration of Authority within the Board of Directors and Variability in Firm Performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 60, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.R.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J. Whose Call to Answer: Institutional Complexity and Firms’ CSR Reporting. AMJ 2017, 60, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanacker, T.; Collewaert, V.; Zahra, S.A. Slack Resources, Firm Performance, and the Institutional Context: Evidence from Privately Held European Firms. Strategy Manag. J. 2016, 38, 1305–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Ahuja, G. Does It Pay to Be Green? An Empirical Examination of the Relationship Between Emission Reduction and Firm Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1996, 5, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Keim, G.D.; Schuler, D. Corporate Political Activity: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.; Graves, S. The Corporate Social Performance-Financial Performance Link. Strategy Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Qian, C. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in China: Symbol or Substance? Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, S.; He, C. How Do Environmental Regulations Affect Industrial Dynamics? Evidence from China’s Pollution-Intensive Industries. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.; Ma, D.; Rawski, T.G. From Divergence to Convergence: Reevaluating the History behind China’s Economic Boom. J. Econ. Lit. 2014, 52, 45–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Annual Report 2000 Marketization Index for China’s Provinces. China World Econ. 2001, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.C. Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Gam, Y.K.; Gupta, P.; Im, J.; Shin, H. Evasive shareholder meetings and corporate fraud. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barko, T.; Cremers, M.; Renneboog, L. Shareholder Engagement on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 777–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Fowler, H.R.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Johnson, J.L. The Role of Board Environmental Committees in Corporate Environmental Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Dong, Y.; Vagnani, G.; Liu, P. Green Innovation and the Stock Market Value of Heavily Polluting Firms: The Role of Environmental Compliance Costs and Technological Collaboration. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 4938–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, R.; Liu, T. How Does Government Attention Matter in Air Pollution Control? Evidence from Government Annual Reports. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Min, B. Green R&D for Eco-Innovation and Its Impact on Carbon Emissions and Firm Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D.W. Reputation Acquisition in Debt Markets. J. Political Econ. 1989, 97, 828–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, L.; Poncet, S. Environmental Policy and Exports: Evidence from Chinese Cities. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 68, 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Sharma, S. A Contingent Resource-Based View of Proactive Corporate Environmental Strategy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Humphery-Jenner, M.; Sautner, Z.; Suchard, J.-A. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions: The role of private equity firms. Strategy Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1688–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-W. State Ownership and Corporate Governance in China: An Executive Career Approach. Columbia Bus. Law Rev. 2014, 2013, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, J.D.; Fredrickson, J.W. Who Directs Strategic Change? Director Experience, the Selection of New CEOs, and Change in Corporate Strategy. Strategy Manag. J. 2001, 22, 1113–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Cannella, A.A.; Paetzold, R.L. The Resource Dependence Role of Corporate Directors: Strategic Adaptation of Board Composition in Response to Environmental Change. J. Manag. Stud. 2000, 37, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottenrott, H.; Peters, B. Innovative Capability and Financing Constraints for Innovation: More Money, More Innovation? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2012, 94, 1126–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D. Resource Orchestration to Create Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1390–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessein, W. Incomplete Contracts and Firm Boundaries: New Directions. J. Law Econ. Organ. 2014, 30, i13–i36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Abu-Allan, A.J.; Alshdaifat, S.M. Board Effectiveness and Carbon Emission Disclosure: Evidence from ASEAN Countries. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, J.D.; Bednar, M.K. The Symbolic Management of Strategic Change: Sensegiving via Framing and Decoupling. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 49, 1173–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, K.T.; Hillman, A. The Effect of Board Capital and CEO Power on Strategic Change. Strategy Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1145–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, M. Varieties of Power in Transnational Labor Alliances: An Analysis of Workers’ Structural, Institutional, and Coalitional Power in the Global Economy. Labor Stud. J. 2013, 38, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, R.A.; You, J. Governance Monitors or Market Rebels? Heterogeneity in Shareholder Activism. Strategy Organ. 2019, 17, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lin, K.; Wang, H. Does Local Green Governance Promote Corporate Green Innovation? A New Perspective from Green Officials. Empir. Econ. 2025, 68, 1861–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M. CEO Power and Open Innovation: Evidence from China. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2025, 28, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, M.; Nath, S.; Sengupta, D. The Race for Net-Zero: Assessing the Role of Energy Efficiency and Conversion Technologies. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2024, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H. Digital Transformation, Employee and Executive Compensation, and Sustained Green Innovation. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 97, 103873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, J.; Henningsson, S. Developing Ecological Sustainability: A Green IS Response Model. Inf. Syst. J. 2016, 26, 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J. Trust and Corruption. In The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust; Uslaner, E.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Green-background directors | GD | Dummy variable, which equals 1 for firms with at least one green-background director in a given year, and 0 otherwise. |

| Power of green-background directors | GP | Aggregate standardized value of GPOWER |

| Corporate green innovation | GPAT | Natural logarithm of the number of green patent applications per firm-year |

| Firm size | Size | Natural logarithm of total assets at year-end |

| Regional marketization level | Market | Marketization level of the province where the company is located |

| Board diligence | BD | Natural logarithm of the number of board meetings held by the company |

| Green investors | GI | Dummy variable, which equals 1 if the company has green investors, and 0 otherwise |

| Corporate environmental attention | EA | Number of environmental keywords in annual report |

| Government green subsidies | EP | Dummy variable, which equals 1 if the company received a government environmental subsidy that year, and 0 otherwise |

| Board size | Board | Natural logarithm of the number of board members |

| Proportion of independent directors | Indep | Number of independent directors divided by total directors |

| CEO–chair duality | Dual | Dummy variable, which equals 1 if the CEO also serves as the board chair, and 0 otherwise |

| R&D investment | RD | Natural logarithm of the R&D investment |

| Leverage ratio | Lev | Total liabilities divided by total assets at year-end |

| Return on assets | ROA | Net profit relative to total assets |

| Revenue growth rate | Growth | (Current year revenue/previous year revenue) − 1 |

| Cash flow ratio | Cash | Operating cash flow scaled by total assets |

| Business years | BY | Natural logarithm of the firm’s operating history |

| Tobin’s Q | TobinQ | (Market value + non-tradable shares × net asset per share + liabilities)/total assets |

| Institutional investor holding percentage | Inst | Shares held by institutional investors divided by total tradable shares |

| Shareholding concentration | Top10 | Shareholding ratio of the top 10 shareholders |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GD | 4368 | 0.361 | 0.480 | 0 | 1 |

| GP | 4368 | 0.065 | 0.123 | 0 | 0.611 |

| GPAT | 4368 | 0.970 | 1.110 | 0 | 4.443 |

| Size | 4368 | 22.24 | 1.267 | 20.15 | 26.00 |

| Market | 4368 | 9.086 | 1.791 | 0.647 | 11.49 |

| BD | 4368 | 2.283 | 0.342 | 0 | 3.638 |

| GI | 4252 | 0.442 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 |

| RD | 4368 | 17.99 | 1.369 | 14.20 | 21.37 |

| EA | 4368 | 4.483 | 5.414 | 0 | 48 |

| EP | 4252 | 0.393 | 0.489 | 0 | 1 |

| Board | 4368 | 2.137 | 0.188 | 1.609 | 2.639 |

| Indep | 4368 | 0.372 | 0.0510 | 0.333 | 0.571 |

| Dual | 4368 | 0.280 | 0.449 | 0 | 1 |

| Lev | 4368 | 0.383 | 0.192 | 0.060 | 0.844 |

| ROA | 4368 | 0.0520 | 0.0570 | −0.127 | 0.210 |

| Growth | 4368 | 0.150 | 0.299 | −0.408 | 1.662 |

| Cash | 4368 | 0.0610 | 0.0610 | −0.105 | 0.223 |

| BY | 4368 | 2.847 | 0.297 | 1.386 | 3.714 |

| TobinQ | 4368 | 1.989 | 1.209 | 0 | 7.230 |

| Inst | 4368 | 0.377 | 0.240 | 0 | 0.870 |

| Top10 | 4368 | 0.594 | 0.147 | 0.254 | 0.902 |

| Variables | GPAT | GD | GP | RD | Lev | Cash | Growth | Indep | Board | Top10 | TobinQ | Inst | BY | Dual | Roa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAT | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| GD | 0.136 *** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| GP | 0.146 *** | 0.700 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| RD | 0.391 *** | 0.0131 | −0.0236 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Lev | 0.320 *** | 0.070 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.203 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Cash | 0.072 *** | 0.009 | −0.033 ** | 0.168 *** | −0.140 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| Growth | 0.065 *** | 0.051 *** | 0.054 *** | 0.107 *** | −0.002 | 0.015 | 1 | ||||||||

| Indep | −0.020 | −0.057 *** | 0.011 | 0.0159 | 0.002 | −0.036 ** | 0.007 | 1 | |||||||

| Board | 0.217 *** | 0.064 *** | −0.013 | 0.132 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.042 *** | −0.033 ** | −0.586 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Top10 | 0.066 *** | −0.023 | −0.018 | 0.104 *** | −0.109 *** | 0.116 *** | 0.140 *** | 0.047 *** | −0.005 | 1 | |||||

| TobinQ | −0.218 *** | −0.057 *** | −0.072 *** | −0.181 *** | −0.320 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.017 | 0 | −0.109 *** | −0.068 *** | 1 | ||||

| Inst | 0.277 *** | −0.019 | −0.006 | 0.276 *** | 0.254 *** | 0.105 *** | −0.007 | −0.026 * | 0.203 *** | 0.269 *** | 0.044 *** | 1 | |||

| BY | 0.071 *** | 0.035 ** | 0.047 *** | 0.0615 *** | 0.147 *** | 0.013 | −0.055 *** | −0.007 | 0.079 *** | −0.196 *** | −0.058 *** | 0.138 *** | 1 | ||

| Dual | −0.190 *** | −0.041 *** | −0.026 * | −0.0624 *** | −0.129 *** | 0.004 | 0.039 *** | 0.084 *** | −0.166 *** | 0.080 *** | 0.068 *** | −0.202 *** | −0.065 *** | 1 | |

| Roa | −0.040 *** | −0.020 | −0.054 *** | 0.147 *** | −0.459 *** | 0.446 *** | 0.288 *** | −0.042 *** | −0.047 *** | 0.232 *** | 0.242 *** | −0.062 *** | −0.074 *** | 0.099 *** | 1 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | |

| GD | 0.315 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.232 *** | 0.124 *** |

| (9.082) | (8.270) | (4.769) | (7.536) | (4.274) | |

| RD | 0.214 *** | 0.272 *** | 0.206 *** | 0.264 *** | |

| (18.293) | (21.577) | (16.104) | (20.772) | ||

| Lev | 1.034 *** | 0.511 *** | 1.071 *** | 0.554 *** | |

| (10.931) | (5.753) | (11.245) | (6.182) | ||

| Cash | 0.553 ** | 0.027 | 0.577 ** | 0.057 | |

| (2.048) | (0.106) | (2.146) | (0.224) | ||

| Growth | 0.114 ** | 0.107 ** | 0.090 | 0.078 | |

| (2.213) | (2.128) | (1.621) | (1.506) | ||

| Indep | 1.588 *** | 1.275 *** | 1.603 *** | 1.289 *** | |

| (4.449) | (3.842) | (4.380) | (3.912) | ||

| Board | 0.783 *** | 0.580 *** | 0.800 *** | 0.599 *** | |

| (7.842) | (5.937) | (7.405) | (6.152) | ||

| Top10 | 0.089 | −0.146 | 0.022 | −0.198 * | |

| (0.797) | (−1.425) | (0.203) | (−1.923) | ||

| TobinQ | −0.093 *** | −0.046 *** | −0.098 *** | −0.048 *** | |

| (−7.002) | (−3.880) | (−7.736) | (−3.877) | ||

| Inst | 0.539 *** | 0.507 *** | 0.579 *** | 0.540 *** | |

| (7.500) | (7.343) | (7.920) | (7.784) | ||

| BY | −0.031 | −0.065 | −0.094 * | −0.126 ** | |

| (−0.613) | (−1.345) | (−1.774) | (−2.460) | ||

| Dual | −0.260 *** | −0.170 *** | −0.261 *** | −0.172 *** | |

| (−7.838) | (−5.903) | (−8.720) | (−6.023) | ||

| Roa | 0.607 * | 0.610 * | 0.664 * | 0.644 ** | |

| (1.724) | (1.858) | (1.940) | (1.970) | ||

| Constants | 0.856 *** | −5.624 *** | −5.715 *** | −5.313 *** | −5.427 *** |

| (41.123) | (−14.553) | (−14.912) | (−12.791) | (−14.092) | |

| Year FE | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 |

| R2 | 0.019 | 0.280 | 0.378 | 0.286 | 0.383 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | |

| GP | 1.320 *** | 1.088 *** | 0.685 *** | 1.028 *** | 0.623 *** |

| (9.776) | (8.979) | (5.226) | (7.798) | (4.766) | |

| RD | 0.219 *** | 0.274 *** | 0.210 *** | 0.265 *** | |

| (18.741) | (21.699) | (16.514) | (20.875) | ||

| Lev | 1.014 *** | 0.509 *** | 1.053 *** | 0.552 *** | |

| (10.750) | (5.723) | (11.086) | (6.160) | ||

| Cash | 0.611 ** | 0.073 | 0.636 ** | 0.102 | |

| (2.273) | (0.290) | (2.392) | (0.405) | ||

| Growth | 0.105 ** | 0.101 ** | 0.078 | 0.070 | |

| (2.042) | (2.015) | (1.407) | (1.365) | ||

| Indep | 1.528 *** | 1.245 *** | 1.547 *** | 1.264 *** | |

| (4.298) | (3.759) | (4.240) | (3.842) | ||

| Board | 0.831 *** | 0.611 *** | 0.846 *** | 0.629 *** | |

| (8.348) | (6.286) | (7.906) | (6.492) | ||

| Top10 | 0.086 | −0.142 | 0.018 | −0.195 * | |

| (0.774) | (−1.390) | (0.167) | (−1.893) | ||

| TobinQ | −0.090 *** | −0.045 *** | −0.095 *** | −0.048 *** | |

| (−6.768) | (−3.838) | (−7.487) | (−3.829) | ||

| Inst | 0.522 *** | 0.498 *** | 0.563 *** | 0.533 *** | |

| (7.289) | (7.211) | (7.738) | (7.672) | ||

| BY | −0.040 | −0.070 | −0.105 ** | −0.131 ** | |

| (−0.797) | (−1.430) | (−1.984) | (−2.557) | ||

| Dual | −0.262 *** | −0.171 *** | −0.263 *** | −0.174 *** | |

| (−7.922) | (−5.975) | (−8.788) | (−6.089) | ||

| Roa | 0.625 * | 0.625 * | 0.678 ** | 0.657 ** | |

| (1.781) | (1.905) | (1.988) | (2.013) | ||

| Constants | 0.884 *** | −5.740 *** | −5.777 *** | −5.421 *** | −5.484 *** |

| (47.075) | (−14.899) | (−15.074) | (−13.107) | (−14.233) | |

| Year FE | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 |

| R2 | 0.021 | 0.285 | 0.380 | 0.292 | 0.385 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | |

| GDN | 0.242 *** | 0.183 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.175 *** | 0.095 *** |

| (12.389) | (10.711) | (5.592) | (9.261) | (5.217) | |

| Constants | 0.847 *** | −5.443 *** | −5.612 *** | −5.149 *** | −5.335 *** |

| (43.900) | (−14.154) | (−14.664) | (−12.495) | (−13.874) | |

| Year FE | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Control variables | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 |

| R2 | 0.034 | 0.287 | 0.380 | 0.293 | 0.385 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | |

| GUNIND | 0.174 *** | 0.131 *** | ||

| (4.781) | (2.806) | |||

| GC | 0.198 *** | |||

| (3.887) | ||||

| GIND | 0.049 | |||

| (1.324) | ||||

| RD | 0.265 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.266 *** | 0.254 *** |

| (20.923) | (19.073) | (20.883) | (18.477) | |

| Lev | 0.546 *** | 0.577 *** | 0.552 *** | 0.564 *** |

| (6.094) | (6.305) | (6.147) | (5.890) | |

| Cash | 0.101 | 0.309 | 0.085 | 0.248 |

| (0.399) | (1.170) | (0.334) | (0.888) | |

| Growth | 0.076 | 0.061 | 0.077 | 0.055 |

| (1.467) | (1.134) | (1.496) | (0.980) | |

| Indep | 1.326 *** | 1.465 *** | 1.341 *** | 1.279 *** |

| (4.043) | (4.336) | (4.083) | (3.606) | |

| Board | 0.602 *** | 0.599 *** | 0.632 *** | 0.499 *** |

| (6.211) | (5.834) | (6.501) | (4.586) | |

| Top10 | −0.201 * | −0.123 | −0.199 * | −0.141 |

| (−1.952) | (−1.156) | (−1.930) | (−1.272) | |

| TobinQ | −0.047 *** | −0.043 *** | −0.046 *** | −0.047 *** |

| (−3.801) | (−3.379) | (−3.716) | (−3.561) | |

| Inst | 0.532 *** | 0.506 *** | 0.529 *** | 0.451 *** |

| (7.649) | (7.057) | (7.624) | (5.940) | |

| BY | −0.125 ** | −0.139 *** | −0.137 *** | −0.071 |

| (−2.445) | (−2.600) | (−2.681) | (−1.251) | |

| Dual | −0.177 *** | −0.172 *** | −0.166 *** | −0.150 *** |

| (−6.175) | (−5.797) | (−5.762) | (−4.812) | |

| Roa | 0.624 * | 0.632 * | 0.598 * | 0.591 * |

| (1.918) | (1.871) | (1.828) | (1.663) | |

| Constants | −5.459 *** | −5.247 *** | −5.493 *** | −5.245 *** |

| (−14.193) | (−13.087) | (−14.204) | (−12.329) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 3932 | 4368 | 3483 |

| R2 | 0.384 | 0.378 | 0.383 | 0.355 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPP | GPP | GPP | GPP | |

| GD | 0.028 *** | 0.017 *** | ||

| (6.264) | (3.657) | |||

| GP | 0.166 *** | 0.121 *** | ||

| (9.509) | (5.335) | |||

| RD | −0.007 *** | −0.006 *** | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (−3.772) | (−3.413) | (−0.158) | (−0.082) | |

| Lev | 0.103 *** | 0.099 *** | 0.062 *** | 0.061 *** |

| (7.274) | (7.039) | (4.219) | (4.168) | |

| Cash | 0.030 | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.011 |

| (0.749) | (0.921) | (0.065) | (0.240) | |

| Growth | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| (1.017) | (0.774) | (0.798) | (0.538) | |

| Indep | −0.035 | −0.042 | −0.036 | −0.038 |

| (−0.663) | (−0.784) | (−0.740) | (−0.784) | |

| Board | 0.013 | 0.019 | −0.004 | 0.001 |

| (0.866) | (1.281) | (−0.323) | (0.097) | |

| Top10 | −0.038 ** | −0.039 ** | −0.044 ** | −0.043 ** |

| (−2.296) | (−2.329) | (−2.577) | (−2.522) | |

| TobinQ | −0.007 *** | −0.006 *** | −0.006 *** | −0.006 *** |

| (−3.497) | (−3.234) | (−3.008) | (−2.969) | |

| Inst | 0.030 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.032 *** |

| (2.819) | (2.671) | (2.910) | (2.832) | |

| BY | −0.005 | −0.007 | −0.007 | −0.007 |

| (−0.664) | (−0.878) | (−0.795) | (−0.877) | |

| Dual | −0.024 *** | −0.024 *** | −0.017 *** | −0.017 *** |

| (−4.905) | (−4.936) | (−3.608) | (−3.649) | |

| Roa | 0.117 ** | 0.120 ** | 0.100 * | 0.103 * |

| (2.223) | (2.295) | (1.803) | (1.870) | |

| Constants | 0.182 *** | 0.165 *** | 0.132 ** | 0.119 ** |

| (3.157) | (2.865) | (2.338) | (2.100) | |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 |

| R2 | 0.049 | 0.060 | 0.121 | 0.127 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | |

| GD | 0.405 *** | 0.259 *** | 0.240 *** | |||

| (8.188) | (5.065) | (7.576) | ||||

| GP | 1.791 *** | 1.328 *** | 1.012 *** | |||

| (9.508) | (6.131) | (9.277) | ||||

| 2015.year | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| (.) | (.) | |||||

| 2016.year | 0.263 *** | 0.261 *** | ||||

| (3.998) | (3.978) | |||||

| 2017.year | 0.298 *** | 0.305 *** | ||||

| (4.720) | (4.826) | |||||

| 2018.year | 0.317 *** | 0.327 *** | ||||

| (5.092) | (5.261) | |||||

| 2019.year | 0.190 *** | 0.198 *** | ||||

| (3.030) | (3.167) | |||||

| 2020.year | 0.290 *** | 0.291 *** | ||||

| (4.637) | (4.658) | |||||

| Constants | −8.980 *** | −9.121 *** | −9.250 *** | −9.328 *** | −5.186 *** | −5.325 *** |

| (−14.018) | (−14.280) | (−11.956) | (−12.121) | (−13.407) | (−13.715) | |

| var (e.GPAT) | 2.077 *** | 2.060 *** | ||||

| (32.274) | (32.278) | |||||

| sigma_u | 1.113 *** | 1.103 *** | ||||

| (29.670) | (29.613) | |||||

| sigma_e | 0.922 *** | 0.921 *** | ||||

| (58.477) | (58.497) | |||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | |

| GD | 0.126 *** | 0.095 *** | ||

| (4.316) | (2.639) | |||

| GP | 0.649 *** | 0.559 *** | ||

| (5.195) | (3.121) | |||

| Constants | −5.510 *** | −5.569 *** | 0.323 | 0.221 |

| (−13.763) | (−13.903) | (0.248) | (0.170) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year and Ind FEs | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Year and Code FEs | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4164 | 4164 | 4298 | 4298 |

| R-sq | 0.383 | 0.386 | 0.765 | 0.765 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | |

| GD | 0.132 *** | |

| (4.688) | ||

| GP | 0.654 *** | |

| (5.613) | ||

| Size | 0.321 *** | 0.321 *** |

| (14.320) | (14.358) | |

| Interact1 | 0.082 *** | |

| (3.519) | ||

| Interact2 | 0.343 *** | |

| (3.924) | ||

| Constants | −9.580 *** | −9.663 *** |

| (−21.044) | (−21.248) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | Yes | Yes |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 |

| R2 | 0.419 | 0.422 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | |

| GD | 0.124 *** | |

| (4.308) | ||

| GP | 0.647 *** | |

| (5.289) | ||

| market | −0.006 | −0.006 |

| (−0.788) | (−0.804) | |

| Interact3 | −0.064 *** | |

| (−4.273) | ||

| Interact4 | −0.296 *** | |

| (−4.322) | ||

| Constants | −5.364 *** | −5.446 *** |

| (−13.941) | (−14.127) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | Yes | Yes |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 |

| R2 | 0.385 | 0.388 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | |

| GD | 0.116 *** | |

| (4.030) | ||

| GP | 0.579 *** | |

| (4.616) | ||

| BD | 0.171 *** | 0.168 *** |

| (4.181) | (4.138) | |

| Interact5 | 0.105 | |

| (1.221) | ||

| Interact6 | 0.610 * | |

| (1.661) | ||

| Constants | −5.730 *** | −5.789 *** |

| (−14.753) | (−14.902) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | Yes | Yes |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 |

| R2 | 0.385 | 0.387 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | |

| GD | 0.126 *** | |

| (4.285) | ||

| GP | 0.677 *** | |

| (5.436) | ||

| GI | 0.146 *** | 0.148 *** |

| (4.720) | (4.792) | |

| Interact7 | 0.126 ** | |

| (2.102) | ||

| Interact8 | 1.032 *** | |

| (4.125) | ||

| Constants | −5.245 *** | −5.300 *** |

| (−13.190) | (−13.383) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | Yes | Yes |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4252 | 4252 |

| R2 | 0.386 | 0.390 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| EA | EA | |

| GD | 0.714 *** | |

| (4.190) | ||

| GP | 3.955 *** | |

| (4.585) | ||

| RD | 0.122 * | 0.128 * |

| (1.653) | (1.736) | |

| Lev | 1.400 ** | 1.382 ** |

| (2.519) | (2.491) | |

| Cash | 4.955 *** | 5.231 *** |

| (3.536) | (3.741) | |

| Growth | −0.034 | −0.081 |

| (−0.120) | (−0.292) | |

| Indep | 2.335 | 2.199 |

| (1.210) | (1.138) | |

| Board | 0.636 | 0.816 |

| (1.114) | (1.445) | |

| Top10 | −0.358 | −0.336 |

| (−0.633) | (−0.596) | |

| TobinQ | −0.305 *** | −0.300 *** |

| (−4.786) | (−4.728) | |

| Inst | 0.462 | 0.419 |

| (1.190) | (1.085) | |

| BY | −0.303 | −0.332 |

| (−1.107) | (−1.209) | |

| Dual | −0.683 *** | −0.693 *** |

| (−4.345) | (−4.385) | |

| Roa | 0.182 | 0.269 |

| (0.100) | (0.148) | |

| Constants | 0.659 | 0.288 |

| (0.292) | (0.127) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 |

| R2 | 0.193 | 0.197 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| EP | EP | |

| GD | 0.025 * | |

| (1.672) | ||

| GP | 0.099 * | |

| (1.649) | ||

| RD | −0.015 ** | −0.015 ** |

| (−2.406) | (−2.375) | |

| Lev | 0.206 *** | 0.206 *** |

| (4.161) | (4.169) | |

| Cash | 0.359 *** | 0.367 *** |

| (2.592) | (2.646) | |

| Growth | −0.008 | −0.008 |

| (−0.287) | (−0.319) | |

| Indep | 0.050 | 0.044 |

| (0.279) | (0.244) | |

| Board | −0.031 | −0.026 |

| (−0.600) | (−0.499) | |

| Top10 | −0.378 *** | −0.378 *** |

| (−6.619) | (−6.619) | |

| TobinQ | −0.034 *** | −0.034 *** |

| (−4.631) | (−4.610) | |

| Inst | 0.164 *** | 0.163 *** |

| (4.583) | (4.538) | |

| BY | 0.027 | 0.026 |

| (1.012) | (0.966) | |

| Dual | −0.033 ** | −0.034 ** |

| (−2.026) | (−2.062) | |

| Roa | −0.075 | −0.073 |

| (−0.430) | (−0.416) | |

| Constants | 0.775 *** | 0.769 *** |

| (3.797) | (3.766) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4252 | 4252 |

| R2 | 0.122 | 0.122 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GSub | GSym | GPAT | GSub | GSym | |

| GD | 0.124 *** | 0.066 *** | 0.094 *** | |||

| (4.274) | (2.621) | (3.839) | ||||

| GP | 0.641 *** | 0.273 ** | 0.559 *** | |||

| (5.170) | (2.509) | (5.217) | ||||

| RD | 0.264 *** | 0.202 *** | 0.182 *** | 0.265 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.183 *** |

| (20.772) | (17.536) | (16.578) | (20.875) | (17.563) | (16.682) | |

| Lev | 0.554 *** | 0.259 *** | 0.535 *** | 0.552 *** | 0.259 *** | 0.532 *** |

| (6.182) | (3.292) | (7.133) | (6.160) | (3.292) | (7.088) | |

| Cash | 0.057 | 0.071 | 0.103 | 0.102 | 0.092 | 0.141 |

| (0.224) | (0.318) | (0.499) | (0.405) | (0.413) | (0.688) | |

| Growth | 0.078 | 0.056 | 0.048 | 0.070 | 0.054 | 0.040 |

| (1.506) | (1.252) | (1.096) | (1.365) | (1.203) | (0.932) | |

| Indep | 1.289 *** | 1.467 *** | 0.949 *** | 1.264 *** | 1.452 *** | 0.932 *** |

| (3.912) | (5.021) | (3.253) | (3.842) | (4.966) | (3.200) | |

| Board | 0.599 *** | 0.527 *** | 0.439 *** | 0.629 *** | 0.541 *** | 0.464 *** |

| (6.152) | (6.088) | (5.003) | (6.492) | (6.241) | (5.333) | |

| Top10 | −0.198 * | 0.000 | −0.060 | −0.195 * | 0.001 | −0.056 |

| (−1.923) | (0.005) | (−0.680) | (−1.893) | (0.010) | (−0.640) | |

| TobinQ | −0.048 *** | −0.023 ** | −0.036 *** | −0.048 *** | −0.023 ** | −0.036 *** |

| (−3.877) | (−2.185) | (−3.647) | (−3.829) | (−2.150) | (−3.606) | |

| Inst | 0.540 *** | 0.389 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.533 *** | 0.385 *** | 0.355 *** |

| (7.784) | (6.577) | (6.161) | (7.672) | (6.506) | (6.066) | |

| BY | −0.126 ** | −0.089 ** | −0.084 ** | −0.131 ** | −0.091 ** | −0.087 ** |

| (−2.460) | (−2.003) | (−1.975) | (−2.557) | (−2.061) | (−2.067) | |

| Dual | −0.172 *** | −0.111 *** | −0.121 *** | −0.174 *** | −0.112 *** | −0.122 *** |

| (−6.023) | (−4.508) | (−5.230) | (−6.089) | (−4.550) | (−5.295) | |

| Roa | 0.644 ** | 0.352 | 0.263 | 0.657 ** | 0.357 | 0.276 |

| (1.970) | (1.257) | (0.987) | (2.013) | (1.273) | (1.036) | |

| Constants | −5.427 *** | −4.671 *** | −3.941 *** | −5.484 *** | −4.690 *** | −3.996 *** |

| (−14.092) | (−13.500) | (−11.475) | (−14.233) | (−13.528) | (−11.655) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 | 4368 |

| R2 | 0.383 | 0.303 | 0.349 | 0.385 | 0.303 | 0.352 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | GPAT | |

| GD_lag1 | 0.113 *** | |||||

| (3.391) | ||||||

| GD_lag2 | 0.081 ** | |||||

| (2.067) | ||||||

| GD_lag3 | 0.047 | |||||

| (0.985) | ||||||

| GP_lag1 | 0.498 *** | |||||

| (3.387) | ||||||

| GP_lag2 | 0.349 ** | |||||

| (2.022) | ||||||

| GP_lag3 | 0.412 ** | |||||

| (2.062) | ||||||

| RD | 0.279 *** | 0.293 *** | 0.294 *** | 0.280 *** | 0.294 *** | 0.295 *** |

| (18.863) | (17.808) | (14.668) | (18.925) | (17.828) | (14.762) | |

| Lev | 0.567 *** | 0.626 *** | 0.714 *** | 0.569 *** | 0.626 *** | 0.713 *** |

| (5.410) | (5.010) | (4.783) | (5.430) | (5.016) | (4.796) | |

| Cash | 0.108 | 0.024 | 0.295 | 0.148 | 0.059 | 0.327 |

| (0.366) | (0.070) | (0.737) | (0.503) | (0.173) | (0.818) | |

| Growth | 0.094 | 0.073 | −0.008 | 0.087 | 0.069 | −0.012 |

| (1.596) | (1.046) | (−0.091) | (1.480) | (0.995) | (−0.140) | |

| Indep | 1.442 *** | 1.457 *** | 1.882 *** | 1.425 *** | 1.440 *** | 1.910 *** |

| (3.848) | (3.325) | (3.625) | (3.810) | (3.284) | (3.678) | |

| Board | 0.667 *** | 0.643 *** | 0.750 *** | 0.689 *** | 0.656 *** | 0.768 *** |

| (5.958) | (4.919) | (4.948) | (6.164) | (5.011) | (5.068) | |

| Top10 | −0.178 | −0.252 * | −0.475 *** | −0.174 | −0.247 * | −0.473 *** |

| (−1.438) | (−1.696) | (−2.599) | (−1.411) | (−1.661) | (−2.584) | |

| TobinQ | −0.050 *** | −0.060 *** | −0.052 ** | −0.049 *** | −0.060 *** | −0.050 ** |

| (−3.606) | (−3.217) | (−2.106) | (−3.570) | (−3.205) | (−2.023) | |

| Inst | 0.493 *** | 0.482 *** | 0.431 *** | 0.484 *** | 0.474 *** | 0.426 *** |

| (6.068) | (5.085) | (3.756) | (5.944) | (4.999) | (3.722) | |

| BY | −0.114 * | −0.108 | −0.149 | −0.118 * | −0.111 | −0.155 * |

| (−1.860) | (−1.467) | (−1.638) | (−1.928) | (−1.509) | (−1.706) | |

| Dual | −0.178 *** | −0.169 *** | −0.181 *** | −0.179 *** | −0.168 *** | −0.179 *** |

| (−5.350) | (−4.281) | (−3.795) | (−5.377) | (−4.267) | (−3.769) | |

| Roa | 0.263 | 0.283 | 0.257 | 0.268 | 0.269 | 0.227 |

| (0.706) | (0.647) | (0.502) | (0.719) | (0.615) | (0.443) | |

| Constants | −5.878 *** | −6.040 *** | −6.207 *** | −5.921 *** | −6.064 *** | −6.280 *** |

| (−13.347) | (−12.317) | (−10.825) | (−13.411) | (−12.320) | (−10.890) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ind FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3379 | 2496 | 1704 | 3379 | 2496 | 1704 |

| R2 | 0.399 | 0.410 | 0.422 | 0.400 | 0.410 | 0.424 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Dong, H.; Qi, L. How Directors with Green Backgrounds Drive Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156944

Liu L, Dong H, Qi L. How Directors with Green Backgrounds Drive Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156944

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Liyun, Huaibo Dong, and Lei Qi. 2025. "How Directors with Green Backgrounds Drive Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from China" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156944

APA StyleLiu, L., Dong, H., & Qi, L. (2025). How Directors with Green Backgrounds Drive Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 17(15), 6944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156944