Using System Thinking to Identify Food Wastage (FW) Leverage Points in Four Different Food Chains

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Which FW leverage points are found across the four food chains and chain links?

- -

- Which change in behavioural patterns, structures and mental models could be effective in reducing FW across all food chains?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systems Thinking Approaches

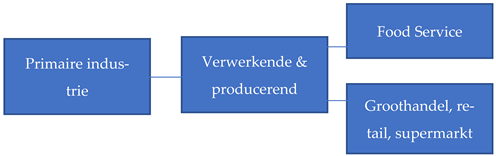

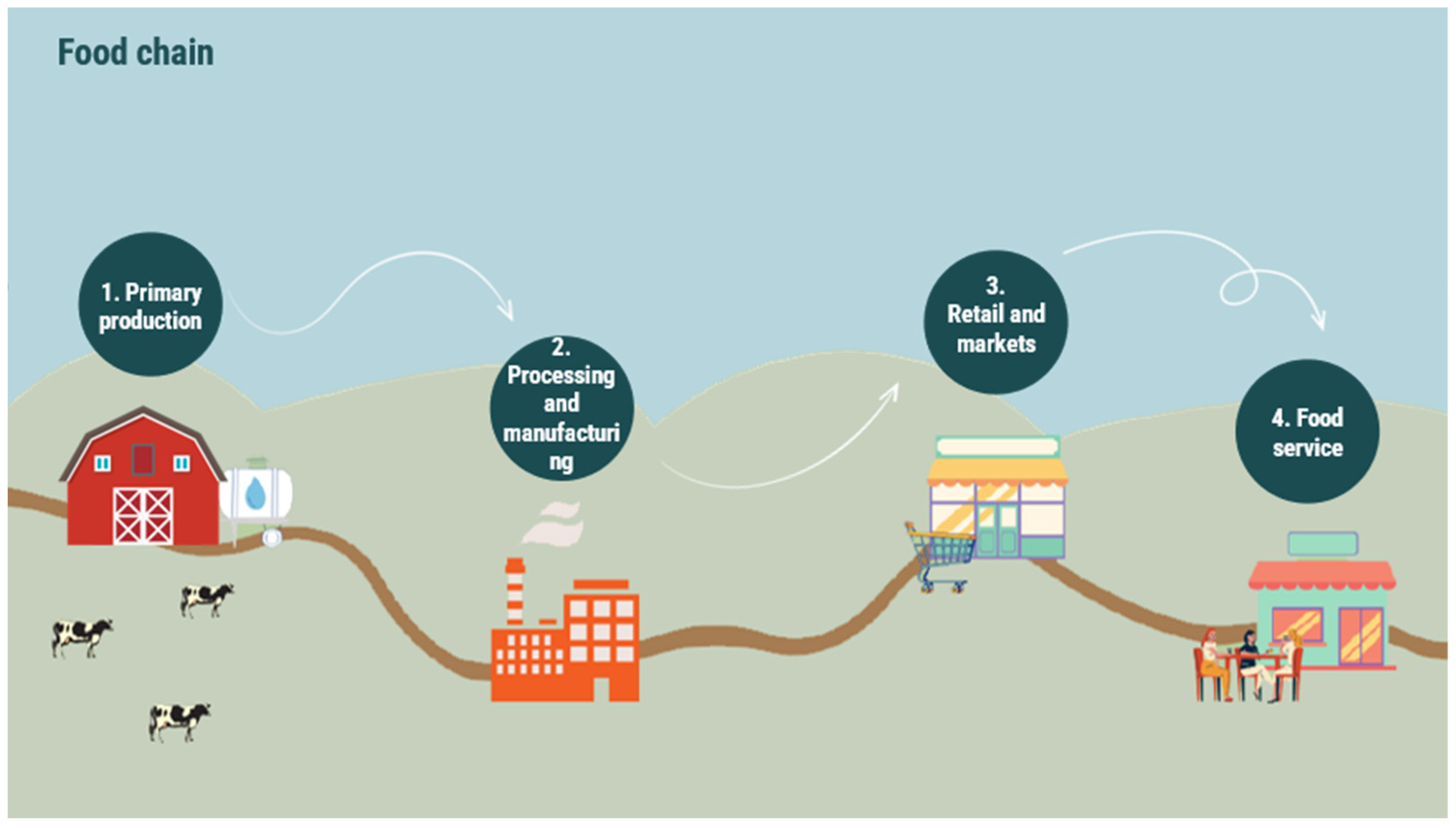

2.2. Food Chains

- (a)

- Relevance to key economic agri-food sectors within the Netherlands;

- (b)

- Existing collaborative relationships between the selected chains and universities of applied sciences;

- (c)

- Representation of both animal-based and plant-based food products that constitute a typical daily diet, acknowledging that animal protein chains have historically exhibited lower levels of food waste due to the relatively higher economic value of animal protein;

- (d)

- The total number of chains included was constrained by limitations in budget and time.

2.3. Interviews

2.4. Validation and Co-Creation of a Preferred Future

3. Results

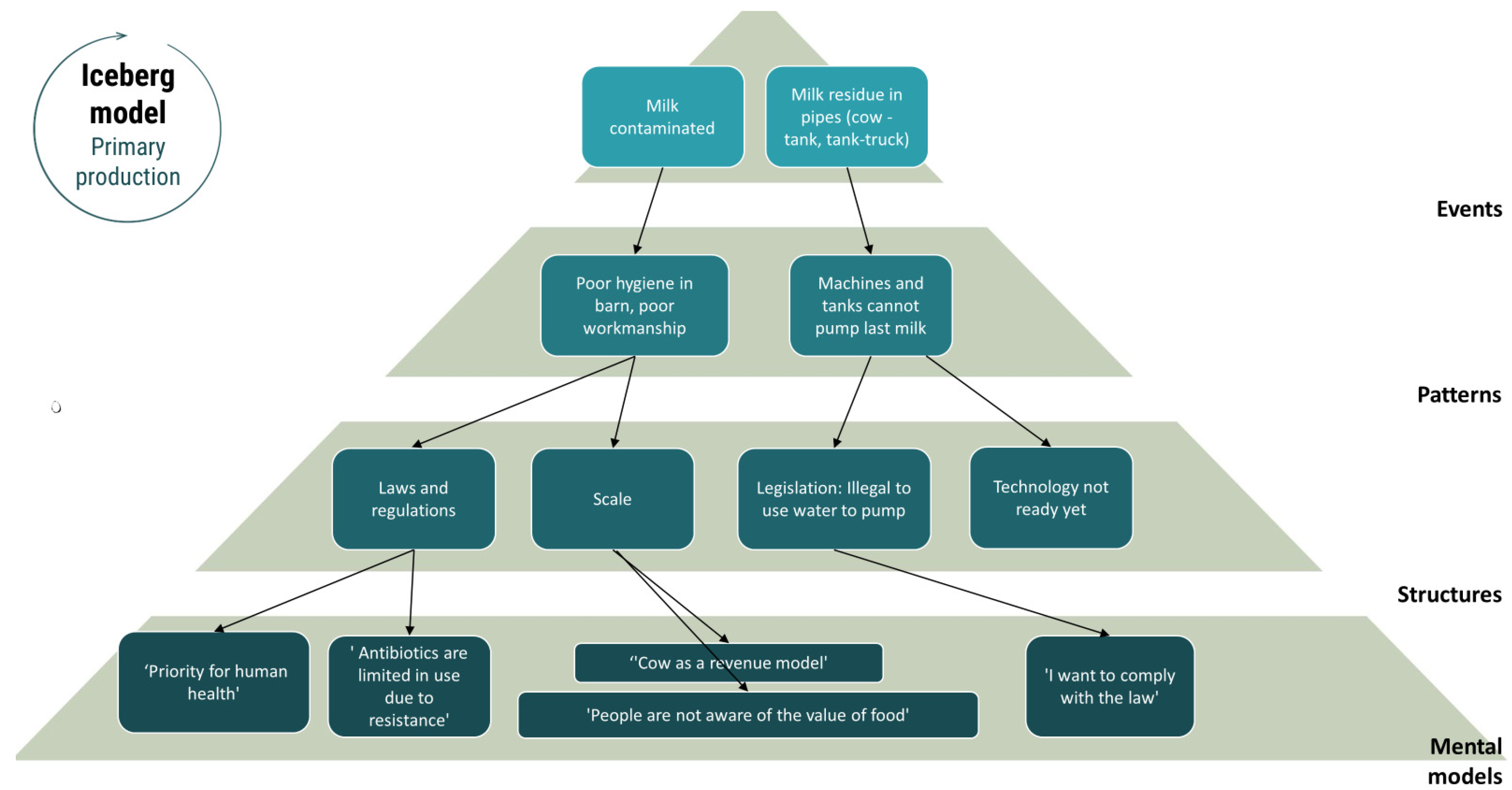

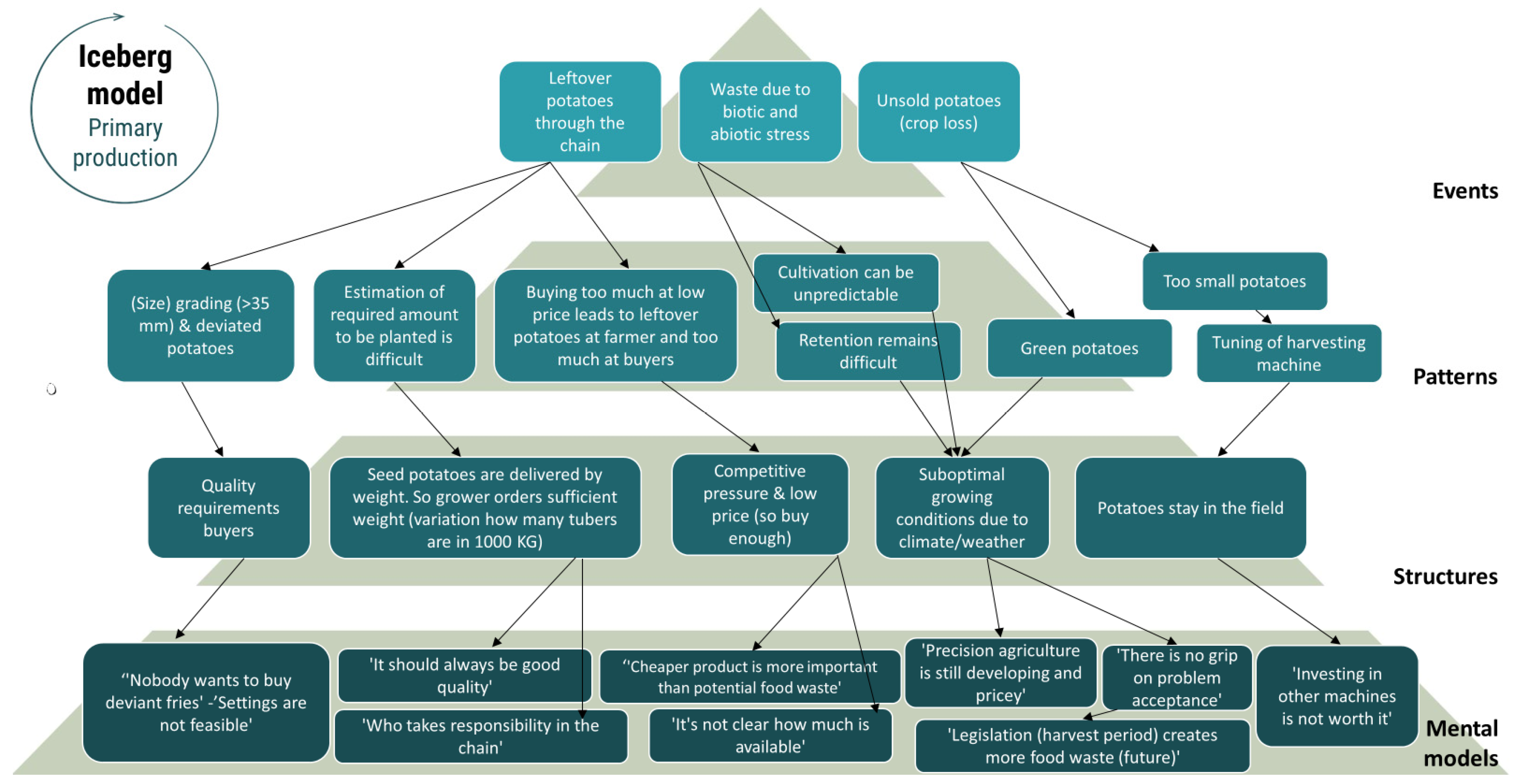

3.1. Primary Production Food Waste Leverage Points

- Damaged starting materials (animals, eggs, seeds);

- Contaminated animals or products due to diseases/pests/control or protection agents;

- Residual flows resulting from the shortcomings of technical processing (cuts from cleaning with water/damaged harvesting machines/machine harvest of unripe or overly small crops).

- Edible but unknown/unloved part of product is wasted (e.g., vegetables, animal parts);

- Damage to product due to suboptimal handling;

- Higher volume produced than demanded.

- Edible but unknown/unloved part of product is wasted (e.g., vegetables, animal parts);

- Product does not meet buyer’s quality requirements;

- Laws sometimes unintentionally force the creation of more FW.

- The product always needs to meet the highest quality standards;

- The consumer would like to have perfect products;

- I am not primarily responsible for prevention of FW;

- Investing in better techniques is not profitable;

- It is more important to offer a competitive price than to prevent food waste;

- Food waste is not seen as a way to reduce energy, water and CO2 emissions;

- Food waste is seen as part of the process;

- Speed of working is more important than prevention of FW.

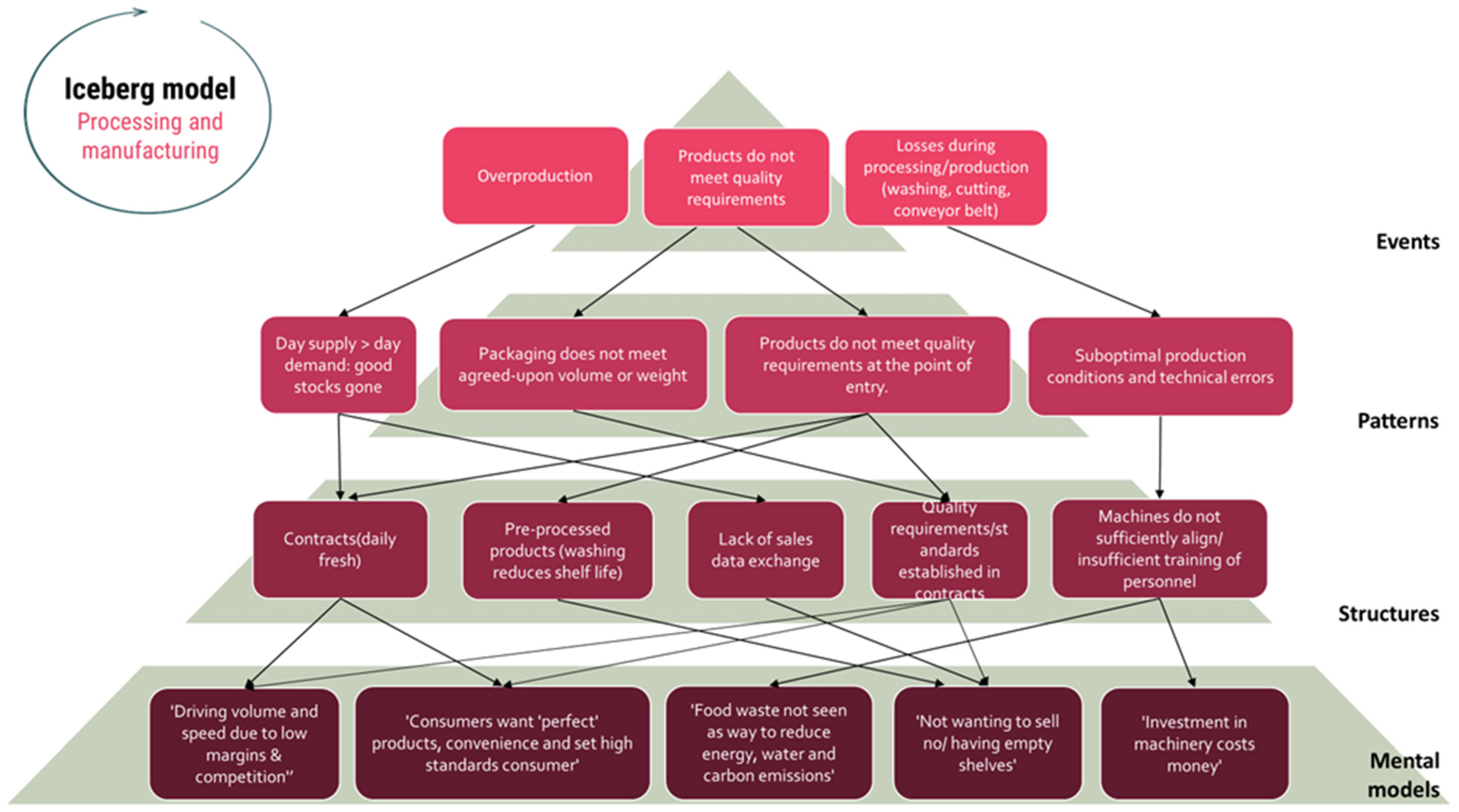

3.2. Processing and Manufacturing Food Waste Leverage Points

- Product rejected—damaged during primary production or during transport;

- Wrong filling volume in packaging.

- Sampling for quality control;

- Product falls off the line;

- Rejection due to spoilage because of insufficient hygiene or storage measures;

- (Packaged) product is not sold due to logistical reasons (incomplete pallet, breach of contract, stored too long);

- Product is not sold because of overproduction;

- Product is produced but not cleared for market.

- Edible but unknown/unloved part of product is wasted (vegetables/meat);

- Product does not meet buyer’s quality requirements;

- Innovation product (product is not sold due to unmet quality standards, proprietary knowledge or risk of image loss);

- Insufficiently trained/skilled personnel.

- There is no priority to invest in alternative technologies;

- FW is seen as part of the process;

- There is pressure to meet quality and consumer standards;

- Reducing FW is not seen as a way to reduce energy, water and CO2 emissions;

- Volumes need to be high enough to meet customer demand;

- Production should be as efficient as possible.

3.3. Retail and Markets

- Products are past their due date;

- Wrong delivery due to wrong order or different product than expected;

- Damage due to transport/spilling or dropping;

- Unsold product.

- Rejection due to spoilage by insufficient hygiene or storage measures (temperature, first-in-first-out principle)—could be summarized as incorrect product handling behaviours;

- Product unsold due to incorrect labelling;

- Unpredictable consumer buying patterns;

- Throwing away products that are past due date;

- Higher volume than demand.

- Product loss is not qualified as FW;

- Insufficient training for employees;

- Forecasting techniques are limited;

- Contractual agreements with regard to high quality.

- Reducing food waste is not a priority;

- Inability to find trained personnel;

- Desire to please customers;

- Oversupply is the norm.

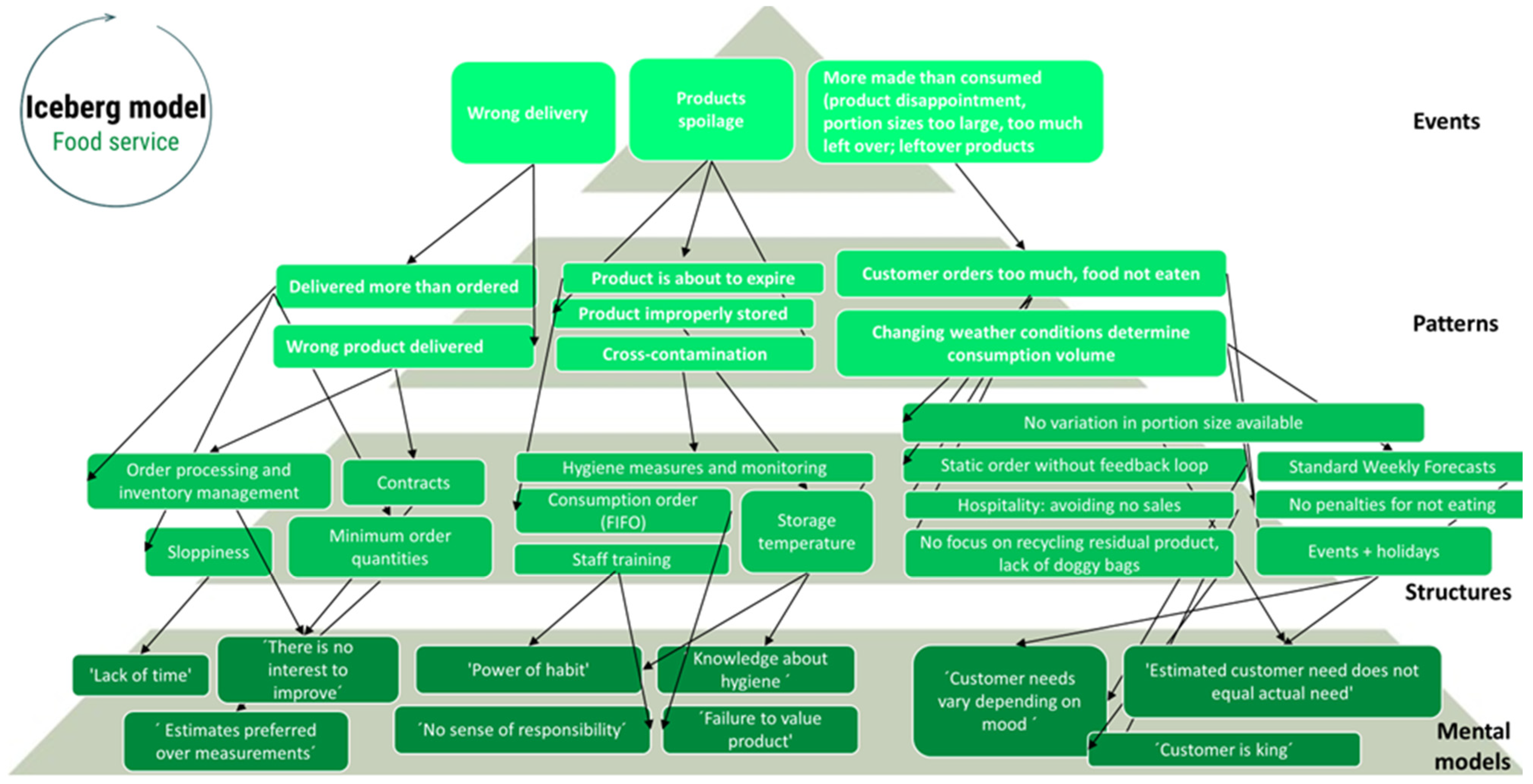

3.4. Food Service

- Wrong delivery/order;

- Product spoilage;

- Product leftovers (on plates).

- Wrong delivery/order;

- Incorrect product handling behaviours (storage measures such as temperature, first-in-first-out principle);

- Varying customer needs;

- (Cutting) waste during preparation—obsolete parts are cut away;

- Customers order too much or refuse product (ordered too much, not tasty, too large a portion).

- HACCP rules lead to product rejection (in Netherlands, product needs to be discarded/not allowed to be stored after 2 h without cooling);

- Demand and volume do not match;

- Limited consequences for the customer when food is not eaten;

- Limited recycling possibility of FW;

- Forecasting techniques are limited.

- There are a lack of possibilities to reduce food waste (such as time, knowledge, tools);

- Customer wishes are set as a priority;

- Acting out of habit rather than taking responsibility to reduce FW.

3.5. Summary Overview of Four Food Chains

4. Discussion

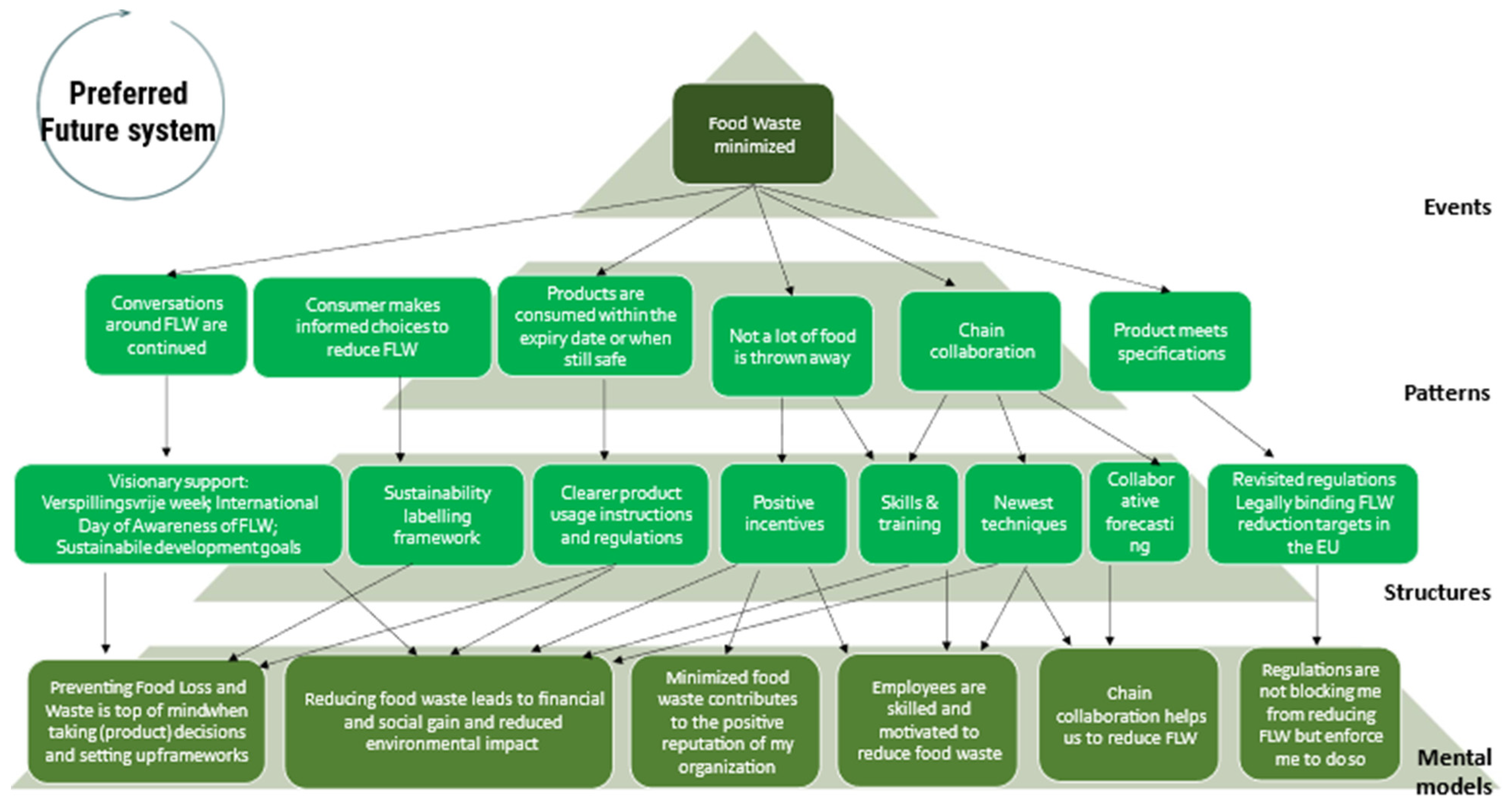

5. Conclusions

- Damaged products;

- Oversupply;

- Regulations and standards that limit product use;

- Lack of prioritization of FW reduction.

- Make food waste a priority by setting rules and regulations but also by showing the advantages in terms of financial, social and environmental value and by creating more awareness of food waste in specific business or chain settings;

- Setting sustainability benchmarks and KPIs for food chains as a shared responsibility;

- Setting standards of best practice and sharing best practices in food chains, combined with training food professionals in food waste reduction within companies;

- Creating new mental models in food service by providing just enough instead of too much;

- Revising food quality standards and regulations where possible with the aim of reducing food waste instead of increasing food waste;

- Stimulating cooperation in food chains by organizing co-creation sessions with food chain representatives in order to start coalitions of willing companies to reduce FW.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide

| Vraag | |||||||||||

| I | INTRO | Namens een onderzoekssamenwerking tussen diverse hogescholen ben ik vandaag bij u. Mijn naam is… Mijn functie is… Wij zijn geïnteresseerd in het in kaart brengen van de zuivel/vlees/AGF keten (de voedsel- en de reststromen). We zijn blij dat u wilt meewerken aan ons onderzoek. | |||||||||

| 1 | U bent aan ons toegewezen voor het in kaart brengen van de voedings- en reststromen binnen het bedrijf. Zou u uzelf willen voorstellen? Hoe kunnen we gedurende dit proces het beste contact onderhouden? Naam en functie: …………………………… Contactgegevens: …………………………… Afspraken:……………………………………........................................................ ……………………………………......................................................................... ……………………………………......................................................................... | ||||||||||

| II | 1 | In hoeverre bent u op de hoogte van het project? | |||||||||

| toelichting | De hogescholen Aeres, Inholland, HAS, HZ en MBO Lentiz hebben als doelstelling om voor de AFG, Zuivel- en vleesketen beter inzicht te krijgen in de voedselverspilling binnen de diverse ketenschakels. We werken nauw samen met de stichting samen tegen voedselverspilling die meewerkt aan het wereldwijde doel om de voedselverspilling te halveren in het jaar 2030 ten opzichte van 2015. Steeds meer bedrijven zetten doelen, meten en verminderen hun voedselverspilling. U als bedrijf neemt deel aan de keten zuivel/vlees/groente en fruit. | ||||||||||

| 2 | Zou u de informed consent kunnen ondertekenen? | ||||||||||

| toelichting | (indien er nog geen contact is geweest in een eerder gesprek) Kies informed consent op basis van interesse Mogelijke onderdelen:

| ||||||||||

| III | 1a | Kunt u in de bijgevoegde schets aangeven waar u bent verbonden met andere schakels in de keten? | |||||||||

| 1b | Van welke type organisaties/bedrijven neemt u af en aan welke type organisaties/bedrijven levert u? | ||||||||||

| 1c | Welke voedselproducten, bijproducten en reststromen worden uitgewisseld? | ||||||||||

| Toelichting 1a/b/c | Afbakenen welke processen en productielocaties in kaart gebracht worden tijdens dit interview. Na het vaststellen van de keten wordt er gekeken naar voedselproducten, bijproducten en reststromen en of deze worden gevaloriseerd. Ook retouren van andere ketenschakels in dit gesprek meenemen. | ||||||||||

| 2a | Hoe definieert u voedselverspilling binnen uw organisatie? | ||||||||||

| Consortium definitie van voedselverspilling: Al het voedsel dat bedoeld is voor menselijke consumptie, maar dat niet door mensen wordt geconsumeerd (Soethoudt & Vollebregt, 2023 [22]) Uitgangspunt hierbij is dat niet de uiteindelijke benutting maar het oorspronkelijke doel (van het voedsel) centraal staat bij de bepaling of er sprake is van verspilling of niet. 2 voorbeelden noemen:…sinaasappelschillen zijn onderdeel van het voedsel en dus verspilling. | |||||||||||

| 2b | Hoe hoog acht u de mate van verspilling binnen uw bedrijf/organisatie? | ||||||||||

| 1. geen verspilling | 2. weinig verspilling | 3. matige verspilling | 4. veel verspilling | 5. erg veel verspilling | |||||||

| Toelichting | Vraag door: kunt u hierop een toelichting geven? Waarom? | ||||||||||

| 2C | Hoe hoog acht u de mate van verspilling binnen uw gehele keten? | ||||||||||

| 1. geen verspilling | 2. weinig verspilling | 3. matige verspilling | 3. veel verspilling | 5. erg veel verspilling | |||||||

| Toelichting | Vraag door: kunt u hierop een toelichting geven? Waarom? Definitie keten: zie Terminologie | ||||||||||

| 3a | Hoe relevant is het terugdringen van voedselverspilling voor uw bedrijf? | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| 3b | Welke doelstelling heeft u als bedrijf op het gebied van het terugdringen van voedselverspilling? | ||||||||||

| 4a | Kunt u opnoemen welke voedsel- en reststromen het meest verspild worden (en welke mogelijk actie vereisen)? Benoem waar in de keten of in het bedrijfsproces deze voedselverspilling ontstaat =verspillingshotspot | ||||||||||

| toelichting | Let op! Deze verspilling kan zowel binnen de ketenschakel als tussen ketenschakels plaatsvinden | ||||||||||

| 4b | Kunt u per verspillingshotspot een inschatting maken hoe hoog deze verspilling is? | ||||||||||

| 1. geen verspilling | 2. weinig verspilling | 3. matige verspilling | 4. veel verspilling | 5. erg veel verspilling | |||||||

| toelichting | |||||||||||

| 4c | Hoe kan deze verspilling worden gedefinieerd? | ||||||||||

| (a) Bijproducten/(b) potentieel vermijdbaar/(c) onvermijdbaar | |||||||||||

| toelichting | Zie begrippenlijst | ||||||||||

| 4d | Wat is de economische waarde van deze verspilling? wat betekent dit concreet: in % van een stroom of financiële waarde | ||||||||||

| Hoge waarde | Lage waarde | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| toelichting | |||||||||||

| 4e | Vindt deze verspilling constant of incidenteel plaats? | ||||||||||

| toelichting | |||||||||||

| 5 | Waardoor wordt volgens u de verspilling veroorzaakt? | ||||||||||

| 6 | Welke interventie is er mogelijk al toegepast? | ||||||||||

| Indien Ja, wat was het resultaat, welke aanpak was effectief? Indien Nee, waarom nog niet en welke interventie zou u willen zien? | |||||||||||

| toelichting | |||||||||||

| 7a | Wat denkt u eruit te kunnen halen door te investeren in het terugdringen van voedselverspilling? | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| 7b | Hoeveel bent u bereid te investeren in het terugdringen van voedselverspilling? | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| 8 | Als we teruggaan naar de verspillingspunten die we in kaart hebben gebracht. Moeten we dan nog meer partijen/mensen benaderen om de verspillingshotspots beter in kaart te brengen. Zo ja, Wie kunnen we benaderen om dit verspillingspunt verder in kaart te brengen? | ||||||||||

| toelichting | Toelichting maak specifiek welke samenwerkingsverbanden nodig zijn binnen de ketenschakel en tussen de ketenschakels, en welke contactpersonen daarvoor benaderd moeten worden Toelichting mogelijkheid WP1? | ||||||||||

| 9 | Welk verspillingspunt zou u als bedrijf als eerste willen aanpakken? | ||||||||||

| toelichting | We willen u hartelijk danken voor uw deelname aan dit interview. Wij zullen een samenvatting maken van uw positionering ten behoeve van voedselverspilling en de inventarisatie van voedselverspillingshotspots. Dit document zal ter verificatie naar u opgestuurd worden en vormt de basis van onze keten analyse die we tijdens de co-creatiesessies delen. | ||||||||||

| Question | |||||||||||

| I | INTRO | On behalf of a research collaboration between several applied, I am with you today. My name is… My job title is… We are interested in mapping the dairy/meat/fresh produce chain (the food and residual streams). We are glad you would like to participate in our research. | |||||||||

| 1 | You are assigned to us for mapping the food and residual streams within the company. Would you like to introduce yourself? How can we best maintain contact during this process? Name and position: …………………………… Contact details: …………………………… Agreements: ……………………………………..................................................... ……………………………………......................................................................... ……………………………………......................................................................... | ||||||||||

| II | 1 | To what extent are you aware of the project? | |||||||||

| explanation | The universities of applied sciences Aeres, Inholland, HAS, HZ and MBO Lentiz aim to gain better insight into food waste within the various chain links for the fresh produce, dairy and meat chain. We are working closely with the Foundation Together Against Food Wastage on the global goal of halving food waste by the year 2030 compared to 2015. More and more companies are setting goals, measuring and reducing their food waste. You as a company participate in the dairy/meat/fruit and vegetable chain. | ||||||||||

| 2 | Could you please sign the informed consent? | ||||||||||

| explanation | Choose informed consent based on interest Possible components:

| ||||||||||

| III | 1a | Can you indicate in the attached sketch where you are connected to other links in the chain? | |||||||||

| 1b | What type of organizations/companies do you purchase from and what type of organizations/companies do you supply to? | ||||||||||

| 1c | What food products, by-products and residual streams are exchanged? | ||||||||||

| Explanation 1a/b/c | Delineate which processes and production sites will be mapped during this interview. After defining the chain, look at food products, by-products and residual streams and whether they are valorized. Also include returns from other chain links in this interview. | ||||||||||

| 2a | How do you define food waste within your organization? | ||||||||||

| Consortium definition of food waste: All food intended for human consumption but not consumed by humans (Soethoudt & Vollebregt, 2023). The premise here is that it is not the final utilization but the original purpose (of the food) that is central in determining whether it is wasted or not. Citing two examples: …orange peels are parts of food and are therefore wasted. | |||||||||||

| 2b | How high do you consider the level of waste within your company/organization? | ||||||||||

| 1. No waste | 2. Little waste | 3. Moderate waste | 4. Lots of waste | 5. A very large amount of waste | |||||||

| Explanation | Can you comment on this? Why? | ||||||||||

| 2C | How high do you consider the level of waste within your entire supply chain? | ||||||||||

| 1. No waste | 2. Little waste | 3. Moderate waste | 4. Lots of waste | 5. A very large amount of waste | |||||||

| Explanation | Can you comment on this? Why? Definition chain: see Terminology | ||||||||||

| 3a | How relevant is reducing food waste to your business? | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| 3b | What goal do you have as a company in terms of reducing food waste? | ||||||||||

| 4a | Can you list which food and residual streams are most wasted (and which may require action)? Name where in the chain or business process this food waste occurs, i.e., a food waste hotspot? | ||||||||||

| Explanation | Note! This waste can occur both within the chain link and between chain links | ||||||||||

| 4b | For each food waste hotspot, can you estimate how high this waste is? | ||||||||||

| 1. No waste | 2. Little waste | 3. Moderate waste | 4. Much waste | 5. A very large amount of waste | |||||||

| Explanation | |||||||||||

| 4c | How can this waste be defined? | ||||||||||

| (a) By-products/(b) potentially avoidable/(c) unavoidable | |||||||||||

| Explanation | See glossary | ||||||||||

| 4d | What is the economic value of this wastage? What does this mean specifically: in % of a stream or financial value | ||||||||||

| High value | Low value | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Explanation | |||||||||||

| 4e | Does this waste occur constantly or occasionally? | ||||||||||

| Explanation | |||||||||||

| 5 | What do you think causes food waste? | ||||||||||

| 6 | What intervention may have been used already? | ||||||||||

| If Yes, what was the result, what approach was effective? If No, why not yet and what intervention would you like to see? | |||||||||||

| Explanation | |||||||||||

| 7a | What do you think you can gain by investing in reducing food waste? | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| 7b | How much are you willing to invest in order to reduce food waste? | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| 8 | If we go back to the food waste hotspots we have mapped, should we then approach more parties/people to better map the food waste hotspots. If yes, who can we approach to further map this waste point? | ||||||||||

| Explanation | Explanation: be specific about which partnerships are needed within the chain link and between the chain links and which contacts should be approached for this purpose. Explanation possibility WP1? | ||||||||||

| 9 | Which food waste hotspot would you, as a company, want to address first? | ||||||||||

| Explanation | We would like to thank you very much for participating in this interview. We will produce summary of your positioning regarding food waste and food waste hotspots. This document will be sent to you for verification and will form the basis of our chain analysis shared during the co-creation sessions. | ||||||||||

References

- World Health Organization. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: Safeguarding Against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019; p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021|UNEP—UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Sustainability Pathways: Food Loss and Waste. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nr/sustainability/food-loss-and-waste/en/ (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Scherhaufer, S.; Moates, G.; Hartikainen, H.; Waldron, K.; Obersteiner, G. Environmental Impacts of Food Waste in Europe. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fight Climate Change by Preventing Food Waste|Stories|WWF. Available online: https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/fight-climate-change-by-preventing-food-waste (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Thyberg, K.L.; Tonjes, D.J. Drivers of Food Waste and Their Implications for Sustainable Policy Development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, M.K.; Birney, C.; Cuéllar, A.; Finn, S.M.; Freeman, M.; Galloway, J.N.; Gee, I.; Gephart, J.; Jones, K.; Low, L.; et al. A Systems Approach to Assessing Environmental and Economic Effects of Food Loss and Waste Interventions in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagherzadeh, M. A Food Systems’ Approach to Food Loss and Waste Open Forum on Resilience in Agriculture. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/about/programmes/co-operative-research-programme/Morvarid%20Bagherzadeh_A%20food%20systems%20approach%20to%20food%20loss%20and%20waste.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Van Berkum, S.; Ruben, R. The Food Systems Approach: Sustainable Solutions for a Sufficient Supply of Healthy Food. Available online: https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/the-food-systems-approach-sustainable-solutions-for-a-sufficient- (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Caldeira, C.; De Laurentiis, V.; Corrado, S.; van Holsteijn, F.; Sala, S. Quantification of Food Waste per Product Group along the Food Supply Chain in the European Union: A Mass Flow Analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canali, M.; Amani, P.; Aramyan, L.; Gheoldus, M.; Moates, G.; Östergren, K.; Silvennoinen, K.; Waldron, K.; Vittuari, M. Food Waste Drivers in Europe, from Identification to Possible Interventions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priefer, C.; Jörissen, J.; Bräutigam, K.R. Food Waste Prevention in Europe—A Cause-Driven Approach to Identify the Most Relevant Leverage Points for Action. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voedselverspilling in Nederlandse Ziekenhuizen—PDF Gratis Download. Available online: https://docplayer.nl/57513681-Voedselverspilling-in-nederlandse-ziekenhuizen.html (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- About FUSIONS. Available online: http://eu-fusions.org/index.php/about-fusions#work-structure (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Monat, J.P.; Gannon, T.F. What Is Systems Thinking? A Review of Selected Literature Plus Recommendations. Am. J. Syst. Sci. 2015, 2015, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maani, K.; Cavana, R.Y. Systems Thinking, System Dynamics: Managing Change and Complexity; Pearson Prentice Hall: Rosedale, New Zealand, 2007; p. 278. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System—The Donella Meadows Project. Available online: https://donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Dorninger, C.; Abson, D.J.; Apetrei, C.I.; Derwort, P.; Ives, C.D.; Klaniecki, K.; Lam, D.P.M.; Langsenlehner, M.; Riechers, M.; Spittler, N.; et al. Leverage points for sustainability transformation: A review on interventions in food and energy systems. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 171, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lectoraatgroep Future Food Systems—HAS Green Academy. Available online: https://www.has.nl/onderzoek/lectoraten/lectoraatgroep-future-food-systems/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Efficient Food Loss & Waste Protocol. Available online: https://sites.google.com/iastate.edu/phlfwreduction/home/efficient-food-loss-waste-protocol (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Kok, M.G.; Castelein, R.B.; Broeze, J.; Snels, J.C.M.A. The EFFICIENT Protocol: A Pragmatic and Integrated Methodology for Food Loss and Waste Quantification, Analysis of Causes and Intervention Design; Wageningen Food & Biobased Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soethoudt, J.M.; Vollebregt, H.M. Monitor Voedselverspilling: Update 2009–2020; (Rapport Wageningen Food & Biobased Research; No. 2403); Wageningen Food & Biobased Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B.; Bokelmann, W. The Significance of Avoiding Household Food Waste—A Means-End-Chain Approach. Waste Manag. 2018, 74, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Bruggen, A.; Nikolic, I.; Kwakkel, J. Modeling with Stakeholders for Transformative Change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, P. A Paradigm Shift in Sustainability: From Lines to Circles. Acta Innov. 2020, 5–16. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343126980_A_Paradigm_Shift_in_Sustainability_from_Lines_to_Circles (accessed on 15 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nicholes, M.J.; Quested, T.E.; Reynolds, C.; Gillick, S.; Parry, A.D. Surely You Don’t Eat Parsnip Skins? Categorising the Edibility of Food Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 147, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Food Loss and Waste Reduction|United Nations. Retrieved 7 July 2023. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/observances/end-food-waste-day (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Xue, L.; Liu, G.; Parfitt, J.; Liu, X.; Van Herpen, E.; Stenmarck, Å.; O’Connor, C.; Östergren, K.; Cheng, S. Missing Food, Missing Data? A Critical Review of Global Food Losses and Food Waste Data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6618–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermindering Voedselverspilling|Voeding|Rijksoverheid.Nl. Available online: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/voeding/vermindering-voedselverspilling (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Food Waste Reduction Targets. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/food-waste/eu-actions-against-food-waste/food-waste-reduction-targets_en (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Verspillingsvrije Week|Samen Tegen Voedselverspilling. Available online: https://samentegenvoedselverspilling.nl/verspillingsvrijeweek (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste—European Commission. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/food-waste/international-day-awareness-food-loss-and-waste_en (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Cattaneo, A.; Federighi, G.; Vaz, S. The Environmental Impact of Reducing Food Loss and Waste: A Critical Assessment. Food Policy 2021, 98, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramyan, L.; Grainger, M.; Logatcheva, K.; Piras, S.; Setti, M.; Stewart, G.; Vittuari, M. Food Waste Reduction in Supply Chains through Innovations: A Review. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2021, 25, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, T.; Bazigou, K.; Katsigianni, A.; Fotiadis, M.; Chroni, C.; Manios, T.; Daliakopoulos, I.; Tsompanidis, C.; Michalodimitraki, E.; Lasaridi, K. The “A2UFood Training Kit”: Participatory Workshops to Minimize Food Loss and Waste. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Reducing Food Waste Behavior among Hospitality Employees through Communication: Dual Mediation Paths. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1881–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser-Amundson, A. A Multi-Stakeholder Partnership to Fight Food Waste in the Hospitality Industry: A Contribution to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 12 and 17. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 30, 2448–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, L.; Reinikainen, A.; Katajajuuri, J.M.; Silvennoinen, K.; Hartikainen, H. Elements Affecting Food Waste in the Food Service Sector. Waste Manag. 2016, 56, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennchen, B. Knowing the Kitchen: Applying Practice Theory to Issues of Food Waste in the Food Service Sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Taheri, B.; Giritlioglu, I.; Gannon, M.J. Tackling Food Waste in All-Inclusive Resort Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, L.; Pak, N.; Potts, M.D. Tackling the Issue of Food Waste in Restaurants: Options for Measurement Method, Reduction and Behavioral Change. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, V.; Holweg, C.; Teller, C. What a Waste! Exploring the Human Reality of Food Waste from the Store Manager’s Perspective. J. Public Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, C.; Holweg, C.; Reiner, G.; Kotzab, H. Retail Store Operations and Food Waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksoz, C.; Mansouri, S.A.; Bourlakis, M. Collaborative Forecasting in the Food Supply Chain: A Conceptual Framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 158, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Information to Consumers—Legislation—European Commission. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/labelling-and-nutrition/food-information-consumers-legislation_en (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Jaeger, S.R.; Machín, L.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Antúnez, L.; Harker, F.R.; Ares, G. Buy, Eat or Discard? A Case Study with Apples to Explore Fruit Quality Perception and Food Waste. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 69, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chain Segment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Chain | Primary Production | Processing and Manufacturing | Retail and Markets | Food Service |

| Milk | 4 milk farmers (2 organic, 2 standard); 1 vet; 1 expert (applied research) | 1 medium milk industry partner (CEO) | 1 franchiser retailer (CEO) | 4 restaurant owners; 3 catering managers; 2 healthcare institutions (1 CEO, 1 nutrition expert); 1 meal box provider (nutrition expert) |

| Poultry | 2 poultry farmers 2 experts (academic research) | 1 large poultry industry professional; 1 large poultry slaughterhouse; 1 carcass processor; 1 expert (applied research) | 1 retailer (owner); 1 online retailer | 2 caterers (CEO); 2 restaurants (CEO) |

| Potato | 3 farmers; 2 potato seed traders | 1 large potato industry professional (R&D manager) | 1 retailer | 1 food service |

| Greenhouse-grown vegetables | 1 farmer | 1 packaging plant (CEO); 1 vegetable slicing/cutting plant (CEO) | - | - |

| Primary Production | Processing and Manufacturing | Retail and Markets | Food Service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  | |

| Event/ Food waste hotspots |

| x | |||

| x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||

| x | x | |||

| Patterns of behaviour |

| x | x | x | x |

| x | ||||

| x | x | |||

| x | x | |||

| x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | ||

| Structures |

| x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | |

| x | ||||

| Mental models |

| x | x | x | x |

| x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verspeek-van der Stelt, A.; Praasterink, F.; Westerink-Duijzer, E.; Spaapen, A.; Maijers, W.; Zuidberg, A. Using System Thinking to Identify Food Wastage (FW) Leverage Points in Four Different Food Chains. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146523

Verspeek-van der Stelt A, Praasterink F, Westerink-Duijzer E, Spaapen A, Maijers W, Zuidberg A. Using System Thinking to Identify Food Wastage (FW) Leverage Points in Four Different Food Chains. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146523

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerspeek-van der Stelt, Annelies, Frederike Praasterink, Evelot Westerink-Duijzer, Ayella Spaapen, Woody Maijers, and Antien Zuidberg. 2025. "Using System Thinking to Identify Food Wastage (FW) Leverage Points in Four Different Food Chains" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146523

APA StyleVerspeek-van der Stelt, A., Praasterink, F., Westerink-Duijzer, E., Spaapen, A., Maijers, W., & Zuidberg, A. (2025). Using System Thinking to Identify Food Wastage (FW) Leverage Points in Four Different Food Chains. Sustainability, 17(14), 6523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146523