Servitization as a Circular Economy Strategy: A Brazilian Tertiary Packaging Industry for Logistics and Transportation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

2.1. The Imperative of Transitioning to Sustainable and Circular Business Models

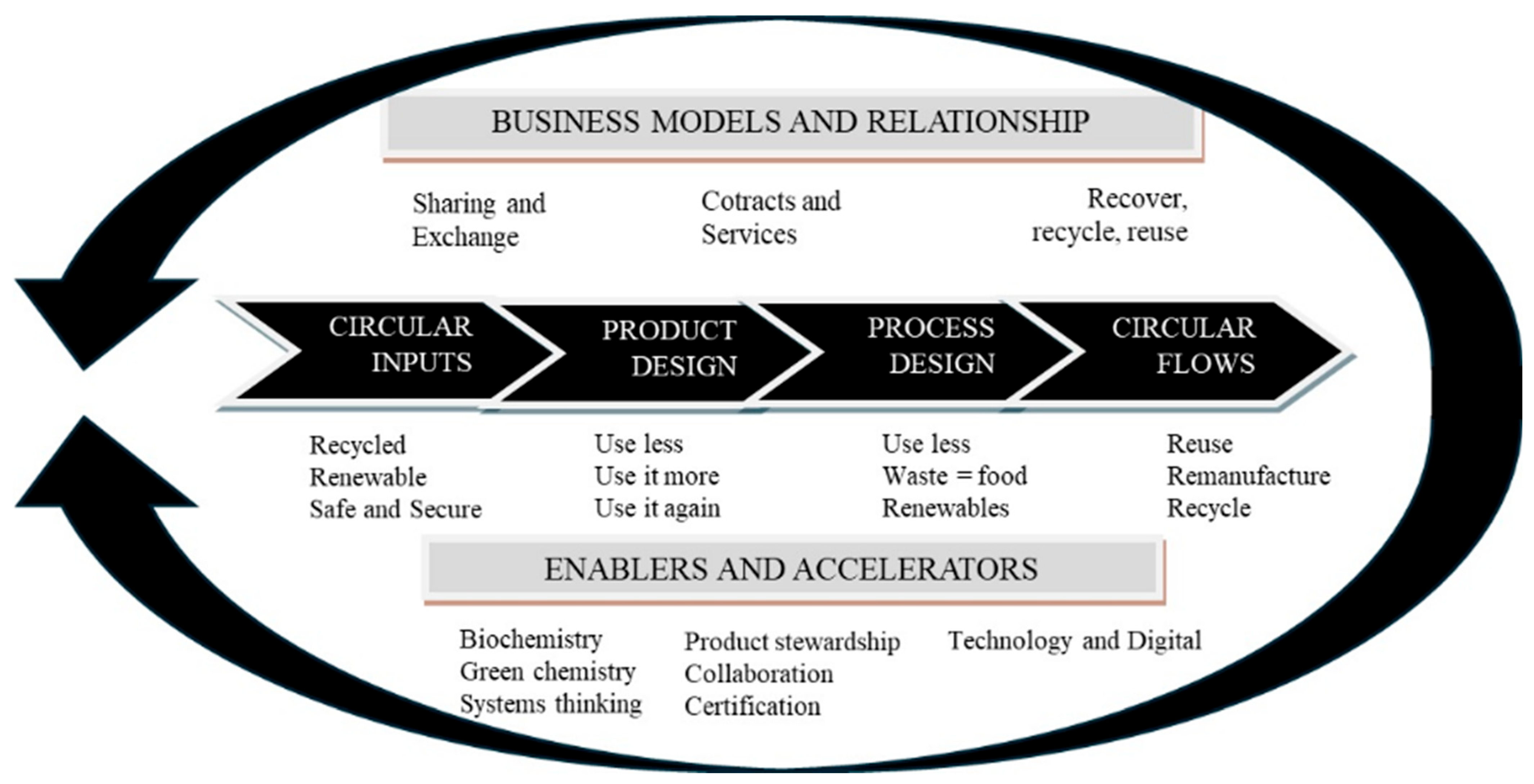

2.2. Processes and Guidelines for Sustainable and Circular Business Models

2.3. Frameworks for the Implementation of the Transition to a Circular Economy Business Model

3. Methodological Procedures

3.1. Approaching the Business Model Design on the Firm Level

- Circular Economy Design: product and system design requires different approaches to enable product reuse, recycling, and “cascading” (destruction of one process becoming input to another).

- Innovative business models to replace or exploit new opportunities: large companies can exploit their scale and vertical integration characteristics as a means of pushing the circular approach into the mainstream (what is considered standard or normal because it is conducted or accepted by the majority) of traditional businesses.

- Reverse cycles: new materials and products cascade, and the final return of materials to the environment or reintegration into the industrial production system requires careful perspectives and new approaches. These include logistics, storage, risk management, energy generation, and sometimes more specific actions (molecular biology, polymer chemistry, etc.).

- Enablers and favorable systemic conditions: new or renewed market mechanisms can encourage widespread reuse of materials and increase resource productivity. We included in this item, the role of eco-labelling and, specific to our context, the Brazilian National Waste Policy (PNRS).

3.2. Approaching the Business Model Design on the Organizational Level of Staff

4. Results

- Circular Economy Design: (a) The company operates in a traditional model of purchasing raw materials, processing, and selling the final product, without considering the reintegration of products into the production cycle after use; (b) there is no reference to ancillary services that could encompass the products’ useful life or their reuse; (c) the only initiative that touches on the circular economy is the sale of trimmings (production waste) for recycling, although this does not necessarily indicate a fully circular approach, it appears to focus more on waste management than on a circular design or production strategy;

- Innovative business models to replace or exploit new opportunities: (a) Comprehension of the concept of servitization and its use in operations has not been examined; (b) the product design does not include reuse, recycling, or cascading, and the products are described as “one-way”, intended for one-time use in the transportation of goods;

- Reverse cycles: (a) There is no indication of circular flow formation or input use in production processes or design initiatives that prioritize resource reuse or minimization; (b) despite a small initiative related to the sale of production waste for recycling, the company does not demonstrate a significant or integrated circular economy approach in its operation, focusing mainly on a linear production model;

- Enablers and favorable systemic conditions: (a) There is a developing Brazilian sectoral agreement on reverse logistics of packaging; (b) the legislation (PNRS) regarding solid waste management reinforcing transitions to the circular economy business model; (c) the possibility of environmental awareness and education of the employees.

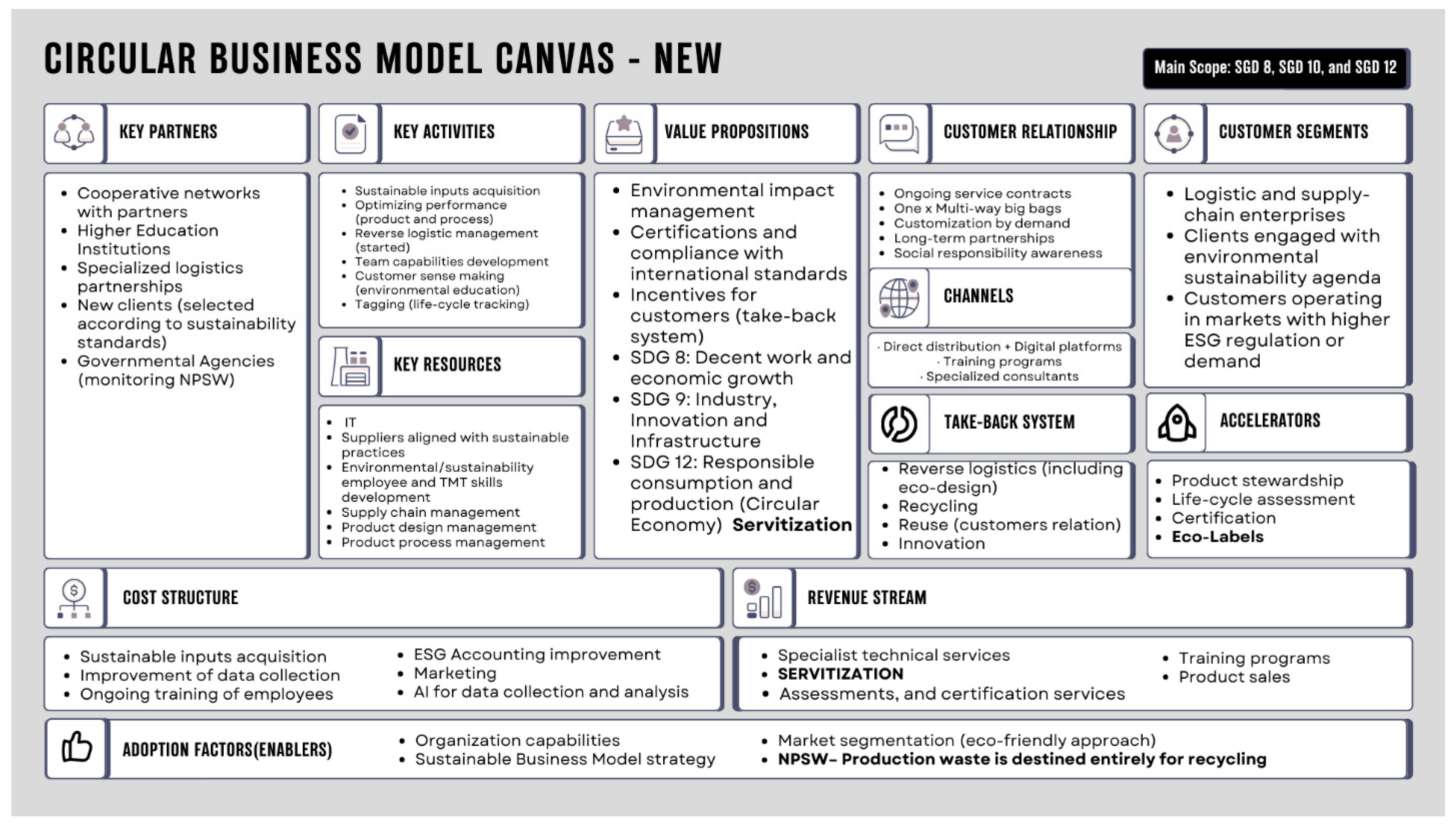

- Take-Back System (reverse logistics);

- Adoption Factors (internal and external).

5. Discussion

- Business model as usual: If there are no alterations to the elements of the BMs.

- Business model adjustment: If some modifications to one element of the BMs occur.

- Business model innovation: If major BM transformations are implemented.

- Business model redesign: If a thorough reevaluation of an organization’s BM components leads to entirely new value propositions.

6. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABRE | Associação Brasileira de Embalagem |

| BM | Business Model |

| CBMC | Circular Business Model Canvas |

| CE | Circular Economy |

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| CETESB | Companhia Ambiental do Estado de São Paulo |

| CLSCs | Closed-Loop Supply Chains |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicators |

| PNRS | Brazilian National Policy on Solid Waste |

| PR | Participatory Research |

| SBM | Sustainable Business Model |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises |

| TLBMC | Triple-Layered Business Model Canvas |

| TLT | Top Leadership Team |

Appendix A

Top Leadership Team Interview Script

- Current Business and Relationship Models

- What is the business and relationship model of the company?

- Does the company engage only in transactional relationships (buying and selling)?

- What types of contractual arrangements are commonly used?

- Is there operational infrastructure sharing with other stakeholders?

- Is there an operational exchange or symbiosis (e.g., industrial symbiosis) in the production chain?

- Recovery, Recycling, and Reuse as ongoing Practices

- Are there relational initiatives focused on the recovery, recycling, or reuse of materials or products?

- Do circular flows in the product or process enable reuse?

- Do circular flows in the product or process enable remanufacturing?

- Do circular flows in the product or process enable recycling?

- Use of Circular Product Design Principles

- Are there circular design initiatives at the origin of the product (design for circularity)?

- Is the product designed from the outset to enable reuse, recycling, or cascading (becoming input for another product)?

- Is the product designed according to the “use less” principle (e.g., resource efficiency or dematerialization)?

- Is the product designed according to the “use longer” principle (e.g., durability, reparability)?

- Is the product designed according to the “use again” principle (e.g., reuse, refurbishing)?

- Maturity of Circularity in the Production Processes

- Are there circular design initiatives in the production process?

- Do the adopted production processes create circular flows (e.g., closed-loop systems)?

- Do the production processes result in circular inputs (e.g., recycled or recovered materials)?

- Is the principle of “using less” applied in the production process?

- Are waste and by-products considered valuable inputs for the process (e.g., waste-to-resource)?

- Are renewable resources integrated into the production processes?

- Use of Circular and Safe Inputs

- Are circular inputs used that allow for recycling?

- Are circular inputs used that allow for renewability (e.g., bio-based materials)?

- Are circular inputs considered that promote safety and protection (e.g., non-toxic, compliant with CE standards)?

References

- Gomes, G.; Wojahn, R.M. Organizational learning capability, innovation and performance: Study in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMES). Rev. Adm. (São Paulo) 2017, 52, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L. Leadership and organizational learning culture: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2019, 43, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva, R.; Alegre, J.; Lapiedra, R. Measuring organisational learning capability among the workforce. Int. J. Manpow. 2007, 28, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, P.A. Introdução: Uma definição da PME. In O Estado da arte da Pequena e Média Empresa: Fundamentos e Desafios; Julien, P.A., Ed.; Editora da UFSC: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Memon, H.A.; Wang, Y.; Marriam, I.; Tebyetekerwa, M. Circular economy and sustainability of the clothing and textile industry. Mater. Circ. Econ. 2021, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Tsagarakis, K.P. An introduction to circular economy and sustainability: Some existing lessons and future directions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weetman, C. A Circular Economy Handbook: How to Build a More Resilient, Competitive and Sustainable Business; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.T.; Iyer-Raniga, U. Circular Business Model Value Dimension Canvas: Tool Redesign for Innovation and Validation through an Australian Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the business models for circular economy—Towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, S. The Four Steps to the Epiphany: Successful Strategies for Products That Win; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, C.A.; Den Hollander, M.C.; Van Hinte, E.; Zijlstra, Y. Products That Last: Product Design for Circular Business Models; TU Delft Library: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Revista de Administração Dom Alberto. 2014. Available online: https://revista.domalberto.edu.br/index.php/revistadeadministracao/issue/view/39 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Cardeal, G.; Höse, K.; Ribeiro, I.; Götze, U. Sustainable business models–canvas for sustainability, evaluation method, and their application to additive manufacturing in aircraft maintenance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Marfil, J.-A.; Arimany-Serrat, N.; Hitchen, E.L.; Viladecans-Riera, C. Recycling technology innovation as a source of competitive advantage: The sustainable and circular business model of a bicentennial company. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J.; Osmani, M.; Grubnic, S.; Díaz, A.I.; Grobe, K.; Kaba, A.; Ünlüer, Ö.; Panchal, R. Implementing a circular economy business model canvas in the electrical and electronic manufacturing sector: A case study approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 36, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staicu, D.; Pop, O. Mapping the interactions between the stakeholders of the circular economy ecosystem applied to the textile and apparel sector in Romania. Manag. Mark. Challenges Knowl. Soc. 2018, 13, 1190–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nations, U. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainability: Origins, present research, and future avenues. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, A.C. Overcoming the separation thesis: The needfor a reconsideration of business and society research. Bus. Soc. 1996, 35, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Cooperative, community-spirited and commercial: Social sustainability at Bendigo Bank. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2007, 14, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, M.V.; Salvador, R.; Prado, G.F.D.; de Francisco, A.C.; Piekarski, C.M. Circular economy as a driver to sustainable businesses. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, E. Towards the Circular Economy, Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur, E. The Virtuous Circle (Volume 7); European Investment Bank: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Bi, J.; Moriguichi, Y. The circular economy: A new development strategy in China. J. Ind. Ecol. 2006, 10, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J. Sustainability labelling schemes: The logic of their claims and their functions for stakeholders. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2003, 12, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendler, L. Sustainability Meta Labelling: An effective measure to facilitate more sustainable consumption and production? J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, A.; Taneja, S.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A. Hey, did you see that label? It’s sustainable!: Understanding the role of sustainable labelling in shaping sustainable purchase behaviour for sustainable development. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 2820–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Chiaroni, D.; Del Vecchio, P.; Urbinati, A. Designing business models in circular economy: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 1734–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S.; Sarkis, J.; Filho, M.G. Unlocking the circular economy through new business models based on large-scale data: An integrative framework and research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, L.; Hartley, K.; Dyakonov, I.; Gupta, H.; van Vuuren, D.; Kirchherr, J. Employee skills for circular business model implementation: A taxonomy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 410, 137027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Law No. 12.305, of August 2, 2010. Establishes the National Solid Waste Policy. Official Gazette of the Federal Executive. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2010/lei/l12305.htm (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Bhatia, M.S.; Kumar, S.; Gangwani, K.K.; Kaur, B. Key capabilities for closed-loop supply chain: Empirical evidence from manufacturing firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 208, 123717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Schuit, C.S.; Kraaijenhagen, C. Experimenting with a circular business model: Lessons from eight cases. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2018, 28, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forge, S. Business models for the computer industry for the next decade: When will the fastest eat the largest? Futures 1993, 25, 923–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boffa, E.; Maffei, A. Classification of Sustainable Business Models: A Literature Review and a Map of Their Impact on the Sustainable Development Goals. FME Trans. 2021, 49, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, C.A.G.; Holgado, M.; Rönnbäck, A.Ö.; Despeisse, M.; Johansson, B. Towards sustainable servitization: A literature review of methods and frameworks. Procedia CIRP 2021, 104, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, G.; Trunova, O. Are UN SDGs useful for capturing multiple values of smart city? Cities 2021, 114, 103193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, P.; Barrie, J. How the Circular Economy Can Revive the Sustainable Development Goals: Priorities for Immediate Global Action, and a Policy Blueprint for the Transition to 2050. Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House: 2024. Available online: https://chathamhouse.soutron.net/Portal/Public/en-GB/RecordView/Index/205377 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Ziegler, R.; Poirier, C.; Lacasse, M.; Murray, E. Circular economy and cooperatives—An exploratory survey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachiewicz, S.; Matejun, M.; Pietras, P.; Szczepańczyk, M. Servitization as a concept for managing the development of small and medium-sized enterprises. Management 2018, 22, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt Morales, C.M.; Sossa, J.W.Z. Circular economy in Latin America: A systematic literature review. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2479–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, D.; Minola, T.; Kalchschmidt, M. Shaping servitization in smes related research A systematic literature review and future research directions. Servitization: A Pathw. Towards A Resilient Product. Sustain. Future 2021, 10, 279. [Google Scholar]

- Salwin, M.; Nehring, K.; Jacyna-Gołda, I.; Kraslawski, A. Product-Service System design–an example of the logistics industry. Arch. Transp. 2022, 63, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J.K.; Teye, G.K.; Dinis, M.A.P. Barriers and challenges to waste management hindering the circular economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.A.C.; Takemoto, L.; Claro, S.R.C. Servitização: Aplicação e avaliação da metodologia TraPSS. Rev. Produção Online 2016, 16, 1393–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwich, E. Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Consumption and Production: Priority Products and Materials; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010; ISBN 978-92-807-3084-5. [Google Scholar]

- Portal da Indústria. Mapa Estratégico da Indústria 2018–2022 (Rev. e atual.). CNI. 2018. Available online: https://static.portaldaindustria.com.br/media/filer_public/ee/50/ee50ea49-2d62-42f6-a304-1972c32623d4/mapa_final_ajustado_leve_out_2018.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Pedrinho, G.C.; Miguel, P.A.C. Transição para servitização: Uma revisão estruturada da literatura. Rev. Produção Online 2021, 21, 518–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, P.; Cerqueira-Streit, J.A.; Batista, L.C. Reverse logistics and the sectoral agreement of packaging industry in Brazil towards a transition to circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaski, T.U.; Ribeiro, F.M.; Pereira, B.R.; Arteaga, L.P.S. Embalagem e Sustentabilidade: Desafios e Orientações no Contexto da Economia Circular; CETESB: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Valle, M.P.V.; Guarnieri, P.; Filippi, A.C.G. Adoção de embalagens plásticas sustentáveis agroalimentares: Um olhar na dinâmica da produção orgânica e sustentável em face da Economia Circular. Interações (Campo Gd.) 2023, 24, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.M.; Corona, B.; ten Klooster, R.; Worrell, E. Sustainability of reusable packaging–Current situation and trends. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. X 2020, 6, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.S.; Moreira, N.B.; Filho, J.M.D. Explorando a Economia Circular: Perspectivas Internacionais em Foco. Rev. Contab. UFBA 2022, 16, e2134. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, A.; Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagosh, J.; Macaulay, A.C.; Pluye, P.; Salsberg, J.; Bush, P.L.; Henderson, J.; Sirett, E.; Wong, G.; Cargo, M.; Herbert, C.P.; et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q. 2012, 90, 311–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, L.M.; Jacquez, F. Participatory research methods–choice points in the research process. J. Particip. Res. Methods 2020, 1, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Tucci, C.L. Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubscher, M.; Marinelli, T. Integration of circular economy in business. In Proceedings of the Conference: Going Green—CARE INNOVATION, Vienna, Austria, 17–20 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, G. Business model innovation to create and capture resource value in future circular material chains. Resources 2014, 3, 248–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Väisänen, J.-M. Digital technologies catalyzing business model innovation for circular economy—Multiple case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Evans, S.; Neely, A.; Greenough, R.; Peppard, J.; Roy, R.; Shehab, E.; Braganza, A.; Tiwari, A.; et al. State-of-the-art in product-service systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2007, 221, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.R. Service-Oriented Product Development Strategies: Product/Service-Systems (PSS) Development; DTU Management: 2010. Available online: https://orbit.dtu.dk/files/5177222/DTU-MAN_PhD-Afhandling_Adrian%20Tan.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Barquet, A.P.B.; de Oliveira, M.G.; Amigo, C.R.; Cunha, V.P.; Rozenfeld, H. Employing the business model concept to support the adoption of product–service systems (PSS). Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Sjödin, D.R.; Wincent, J.; Kohtamäki, M. Mastering the transition to product-service provision: Insights into business models, learning activities, and capabilities. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2014, 57, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Planing, P. Business model innovation in a circular economy reasons for non-acceptance of circular business models. Open J. Bus. Model Innov. 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, J.L.; Chiwenga, K.D.; Ali, K. Collaboration as an enabler for circular economy: A case study of a developing country. Manag. Decis. 2019, 59, 1784–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Environmental management and manufacturing performance: The role of collaboration in the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, Q. Supply chain collaboration: Impact on collaborative advantage and firm performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, R.T.; Alhaidan, H.; Al Halbusi, H.; Al-Swidi, A.K. Do organizations really evolve? The critical link between organizational culture and organizational innovation toward organizational effectiveness: Pivotal role of organizational resistance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gochhayat, J.; Giri, V.N.; Suar, D. Influence of organizational culture on organizational effectiveness: The mediating role of organizational communication. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, R. The Impact of Information Campaigns and Regulations on the Adoption of Reusable Packaging Systems: A Large-Scale Field Data Analysis of Intervention Effects in the Circular Economy. 2024. Available online: https://ebiltegia.mondragon.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.11984/6552/ID236_BURKHARDT_exabstract_The_Impact_of_Information_Campaigns_and.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Jacob, F.; Ulaga, W. The transition from product to service in business markets: An agenda for academic inquiry. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermerwe, S.; Rada, J. Servitization of business: Adding value by adding services. Eur. Manag. J. 1988, 6, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, C.; Gilomen, B. Business models for sustainability: Energy efficiency in urban districts. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, K.; Bjerre, M.; Bisgaard, T.; Høgenhaven, C.; Maria Almasi, A.; Damgaard Grann, E. Green Business Model Innovation: Empirical and Literature Studies; Nordic Council of Ministers: 2012. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:707242/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Batista, L.; Bourlakis, M.; Liu, Y.; Smart, P.; Sohal, A. Supply chain operations for a circular economy. Prod. Plan. Control. 2018, 29, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, B. Focusing on the effectiveness of knowledge transference and green innovation on biotechnology firm growth: The roles played by inspirational leadership and bioentrepreneurial capacity. J. Commer. Biotechnol. 2023, 2, 301. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Value propositions | Provided by circular products are opportunities for extending product life, implementing product–service systems, offering virtual services, and/or promoting shared consumption. Additionally, this element includes the incentives and rewards given to customers for returning used products. |

| 2. Customer segments | Closely related to the value proposition element. The match between the value proposition and the group of customers is shown by the value proposition design. |

| 3. Channels | Potentially virtualized by offering virtual value propositions and delivering them in a virtual manner, selling non-virtualized value propositions through virtual channels, and engaging with customers virtually. |

| 4. Customer relationships | Underlying production on order and/or what customers decide, and social-marketing strategies and relationships with community partners when recycling 2.0 is implemented. |

| 5. Revenue streams | Revenues can be derived from the value propositions, and include payments for a circular product or service, or payments based on the availability, usage, or performance of the product-related service provided. Additionally, revenues might also relate to the value of resources recovered from material loops. |

| 6. Key resources | Selecting suppliers that provide superior materials, virtualizing resources, utilizing materials that can regenerate and replenish natural capital, and/or acquiring resources from customers or third parties intended to be part of the material cycles (ideally closed loops). |

| 7. Key activities | The focus is on enhancing performance by implementing effective housekeeping, optimizing process control, modifying equipment, adopting new technologies, promoting sharing and virtualization, and refining product design to prepare it for material cycles and increase its environmental friendliness (lobbying). |

| 8. Key partnerships | By selecting and collaborating with partners throughout the value and supply chains that bolster the CE. |

| 9. Cost structure | Incorporating financial adjustments from other parts of the CBM, such as the valuation of customer incentives, requires the application of specific evaluation criteria and accounting standards. |

| 10. Take-back system | The structure of the take-back management system, encompassing the channels and customer interactions associated with it. |

| 11. Adoption factors 1 | The shift towards the CBMC requires backing from a range of organizational skills and external influences [PNRS; Brazilian sectoral agreement of reverse logistics of packaging]. |

| 12. Accelerators | Product stewardship, life-cycle assessment, certifications, [eco-labeling]. |

| Customers | Company |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Areas | Description | Degree of Execution | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sales model | A transition from product volume sales to service provision and the retrieval of products post-consumer use | Implemented | Servitization since 2024 |

| Product design/material composition | The modification pertains to the design and engineering of products to enhance the high-quality reuse of the product itself, along with its components and materials | Started | Conclusion in 2025 |

| Data management and IT | Resource optimization necessitates a critical competence: the ability to monitor products, components, and material data | Implemented | Since 2023 |

| Supply loops | Concentrating on optimizing the recovery of owned assets when it is profitable and improving the use of recycled materials and pre-owned components to extract additional value from the flow of products, components, and materials | Not started | In two years |

| Strategic purchases for internal operations | Building dependable partnerships and lasting relationships with both suppliers and customers, including joint creation | Implemented | Since 2023 |

| HR and incentives in human resources | A shift requires appropriate cultural adaptation and the development of capabilities, which can be improved through training programs and incentives | Implemented | At C-Level, for others, in two years |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andrade, A.F.; Hollnagel, H.C.; Santos, F.d.A. Servitization as a Circular Economy Strategy: A Brazilian Tertiary Packaging Industry for Logistics and Transportation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146492

Andrade AF, Hollnagel HC, Santos FdA. Servitization as a Circular Economy Strategy: A Brazilian Tertiary Packaging Industry for Logistics and Transportation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146492

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndrade, Alexandre Fernandes, Heloisa Candia Hollnagel, and Fernando de Almeida Santos. 2025. "Servitization as a Circular Economy Strategy: A Brazilian Tertiary Packaging Industry for Logistics and Transportation" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146492

APA StyleAndrade, A. F., Hollnagel, H. C., & Santos, F. d. A. (2025). Servitization as a Circular Economy Strategy: A Brazilian Tertiary Packaging Industry for Logistics and Transportation. Sustainability, 17(14), 6492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146492