Ethical Perceptions and Trust in Green Dining: A Qualitative Case Study of Consumers in Missouri, USA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

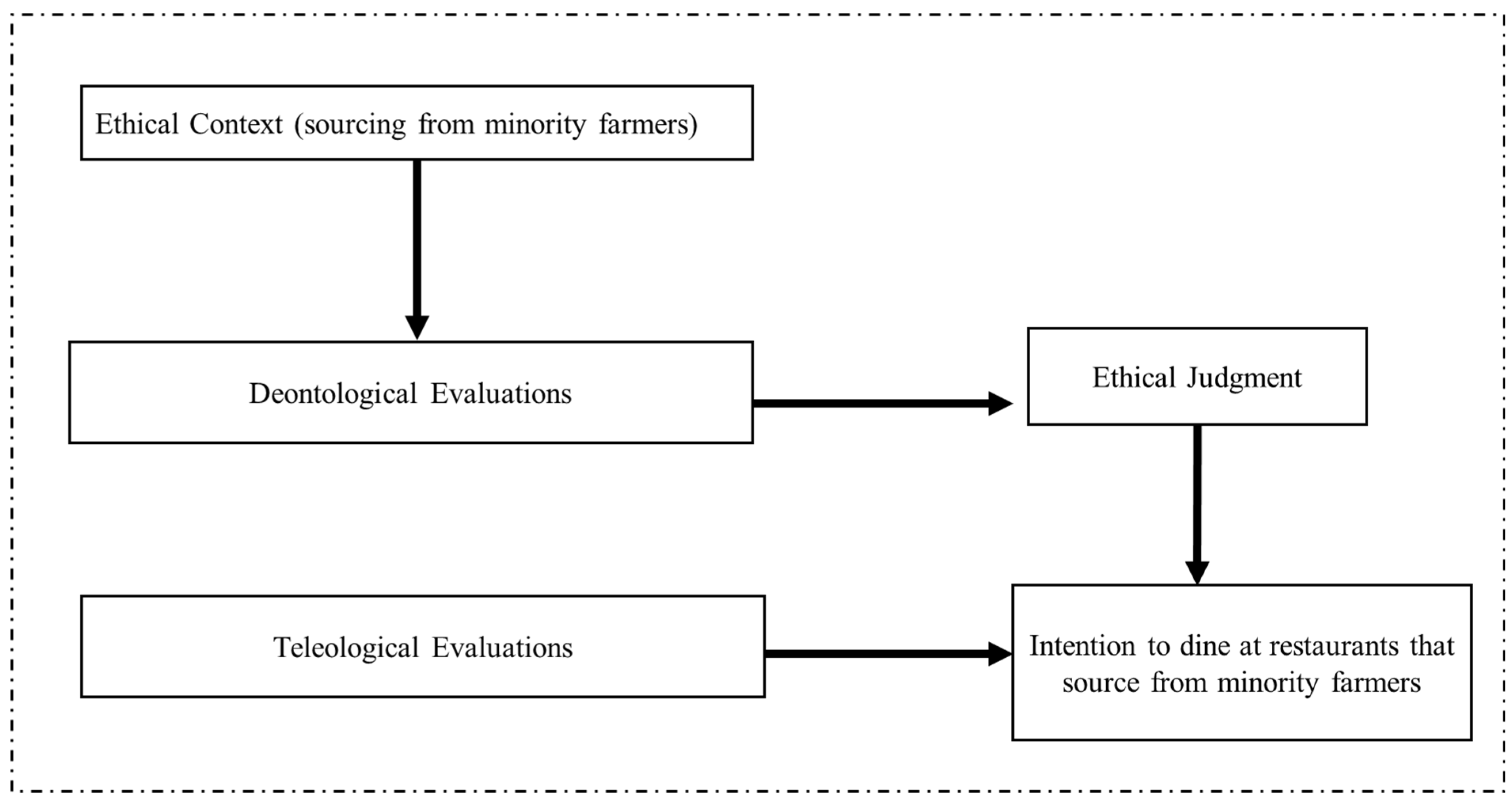

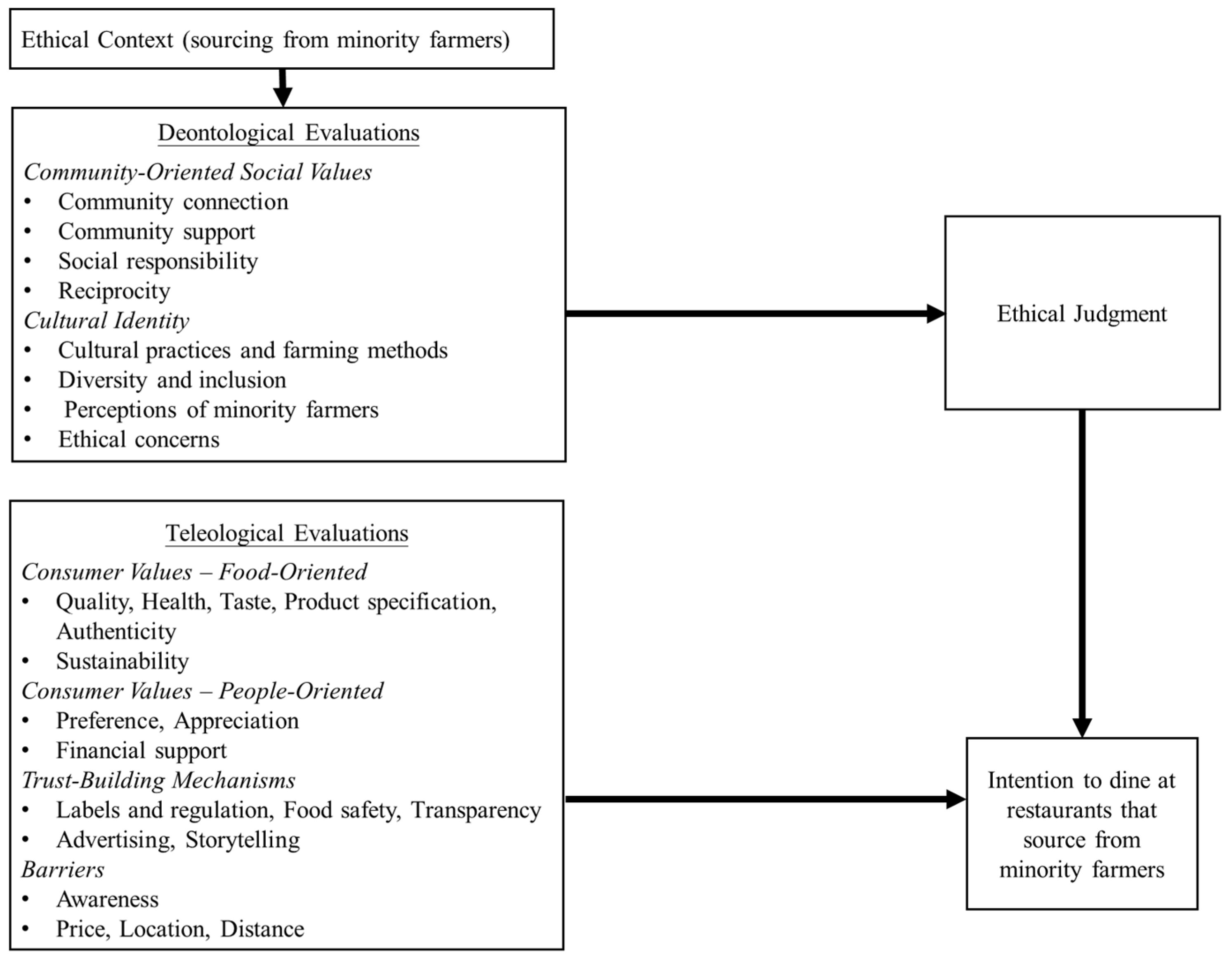

2.1. Theoretical Approach

2.2. Minority Farmers and Consumers’ Moral Obligations

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Recruitment of Participants

3.2. Development of Interview Questions

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

4.2. RQ1-Results for Consumers’ Deontological Evaluations: Social and Cultural Factors Influencing Consumers’ Ethical Judgment

4.2.1. Community-Oriented Social Values

4.2.2. Cultural Identity

4.3. RQ2-Results for Consumers’ Teleological Evaluations: Consumer Values Influencing Dining at Restaurants That Source Local Food

4.3.1. Consumer Values-Food-Oriented

4.3.2. Consumer Values—People-Oriented

4.4. RQ3-Results for Consumers’ Trust-Building Mechanisms and Barriers Influencing Dining at Restaurants That Source Local Food

4.4.1. Trust-Building Mechanisms

4.4.2. Barriers

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitation and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, A.; Jolly, P.M.; Chiles, R.M.; DiPietro, R.B.; Jaykumar, A.; Kesa, H.; Monteiro, H.; Roberts, K.; Saulais, L. Principles of foodservice ethics: A general review. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwart, H. A short history of food ethics. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2000, 12, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frash, R.E., Jr.; DiPietro, R.; Smith, W. Pay more for McLocal? Examining motivators for willingness to pay for local food in a chain restaurant setting. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, R.; Dharmesti, M.; Arcodia, C.; Mahshi, R. UK consumers’ ethical beliefs towards dining at green restaurants: A qualitative evaluation. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J. From big to small: The significance of smallholder farms in the global food system. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.; Qi, R. Ethical labels and conspicuous consumption: Impact on civic virtue and cynicism in luxury foodservice. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1573–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksena, M.J.; Okrent, A.M.; Anekwe, T.D.; Cho, C.; Dicken, C.; Effland, A.; Elitzak, H.; Guthrie, J.; Hamrick, K.; Jo, Y.; et al. America’s Eating Habits: Food Away from Home; United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, R.Y.; Wong, Y.H.; Leung, T.K. Applying ethical concepts to the study of “green” consumer behavior: An analysis of Chinese consumers’ intentions to bring their own shopping bags. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 79, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.C.; Chang, H.H.; Chang, A. Consumer personality and green buying intention: The mediate role of consumer ethical beliefs. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.W.; Chan, R.Y. Why and when do consumers perform green behaviors? An examination of regulatory focus and ethical ideology. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, L.; Mattila, A.S. Consumer response to organic food in restaurants: A serial mediation analysis. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Moon, J.; Strohbehn, C. Restaurant’s decision to purchase local foods: Influence of value chain activities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Cassia, F. Sustainability implementation in restaurants: A comprehensive model of drivers, barriers, and competitiveness-mediated effects on firm performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, A.M.; Green, J.J. Expanding the marketing opportunities and sustainable production potential for minority and limited-resource agricultural producers in Louisiana and Mississippi. J. Rural Soc. Sci. 2008, 23, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hmong American Farmers Association. About HAFA: Our Story. Available online: https://www.hmongfarmers.com/about-hafa/ (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Liu, P.; Eaton, T.E. Barriers to training Hmong produce farmers in the United States: A qualitative study. Food Control 2023, 147, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermann, M.A.; Bartz, P.; Shutske, J.M.; Moua, M.; Vue, P.C.; Lee, T.T. Orphan boy the farmer: Evaluating folktales to teach safety to Hmong farmers. J. Agromed. 2008, 12, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G. Investigating the agricultural techniques used by the Hmong in Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. UW-L J. Undergrad. Res. 2009, XII, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, I.; Balázsné Lendvai, M.; Beke, J. The importance of food attributes and motivational factors for purchasing local food products: Segmentation of young local food consumers in Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. Locally sourced restaurant: Consumers willingness to pay. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, J.J.; Bitto, A.; Brant, G. Core Conservation Practices: Adoption Barriers Perceived by Small and Limited Resource Farmers; Bulletin 646; Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station, Auburn University: Auburn, AL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, H. Connecting farmers’ markets to foodservice businesses: A qualitative exploration of restaurants’ perceived benefits and challenges of purchasing food locally. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2024, 25, 602–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Hall, C.M.; Ballantine, P.W. Connecting local food to foodservice businesses: An exploratory qualitative study on wholesale distributors’ perceived benefits and challenges. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landon, A.; Rosol, M. Overcoming the local trap through inclusive and multi-scalar food systems. Local Environ. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, E.; Mori, K.; Fernandez, S.; Seyyedin, B.; Chinedu-Asogwa, N.; Kapfunde, D. Cultural relevance of food security initiatives and the associated impacts on the cultural identity of immigrants in Canada: A scoping review of food insecurity literature. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2025, 8, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitch, S.; McGregor, J.; Mejía, G.M.; El-Sayed, S.; Spackman, C.; Vitullo, J. Gendered and racial injustices in American food systems and cultures. Humanities 2021, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Vitell, S. A general theory of marketing ethics. J. Macromarketing 1986, 6, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Vitell, S.J. The general theory of marketing ethics: A retrospective and revision. Ethics Mark. 1993, 26, 775–784. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.D.; Vitell, S.J. The general theory of marketing ethics: A revision and three questions. J. Macromarketing 2006, 26, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. Ethical eating as experienced by consumers and producers: When good food meets good farmers. J. Consum. Cult. 2022, 22, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bussel, L.M.; Kuijsten, A.; Mars, M.; Van‘t Veer, P. Consumers’ perceptions on food-related sustainability: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, S.J.; Singhapakdi, A.; Thomas, J. Consumer ethics: An application and empirical testing of the Hunt-Vitell theory of ethics. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.M.; Miah, M.; Biswas, S.; Rahman, S.M. The impact of deontological and teleological variables on the intention to visit green hotel: The moderating role of trust. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.P.L. The effects of emotional self-regulation, ethical evaluations and judgments on customer food waste reduction behaviors in restaurants. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.; Sirgy, M.J.; Bird, M.M. How do managers make teleological evaluations in ethical dilemmas? Testing part of and extending the Hunt-Vitell model. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 26, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satpathy, A.; Samal, A.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S.; Manoharan, G.; Karthikeyan, M.; Sharma, S. To study the sustainable development practices in business and food industry. Migr. Lett. 2024, 21, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcavoy, K. Ethical sourcing: Do consumers and customers really care. Accessed May 2016, 10, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mboga, J. Ethical sourcing to ensure sustainability in the food and beverage industry and eliciting millennial perspectives. Eur. J. Econ. Financ. Res. 2017, 2, 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Batat, W. Consumers’ perceptions of food ethics in luxury dining. J. Serv. Mark. 2022, 36, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.M.; Wu, K.S.; Huang, D.M. The influence of green restaurant decision formation using the VAB model: The effect of environmental concerns upon intent to visit. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8736–8755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Choi, Y.G.; Liu, P.; Lee, Y.M. Food safety training needed for Asian restaurants: Review of multiple health inspection data in Kansas. J. Foodserv. Manag. Educ. 2012, 6, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P. Food Safety Knowledge and Practice in Low-income Families in the United States: An Exploratory Study. Food Prot. Trends 2020, 40, 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, W.D. Concentration of ownership and control in agriculture. In Hungry for Profit: The Agribusiness Threat to Farmers, Food, and the Environment; Monthly Review Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 61–76. Available online: https://search.gesis.org/publication/csa-sa-200110202 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noy, C. Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertaux, D. From the life-history approach to the transformation of sociological practice. In Biography and Society: The Life History Approach in the Social Sciences; Sage: London, UK, 1981; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, H.; Cousins, R.; Young, C. Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: Development and refinement of a codebook. Compr. Psychol. 2014, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Cowley, J. The relevance of stakeholder theory and social capital theory in the context of CSR in SMEs: An Australian perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhu, C.; Fong, L.H.N. Exploring residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards sustainable tourism development in traditional villages: The lens of stakeholder theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, C. Social capital in its place: Using social theory to understand social capital and inequalities in health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J.M. Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. Can business afford to ignore social responsibilities? Calif. Manag. Rev. 1960, 2, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M., Jr. Social support research in community psychology. In Handbook of Community Psychology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, R.; Nair, A.; Griffith, D.A.; Arlbjørn, J.S.; Bendoly, E. Lock-in situations in supply chains: A social exchange theoretic study of sourcing arrangements in buyer–supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.E.; Berdahl, J.L.; Arrow, H. Traits, expectations, culture, and clout: The dynamics of diversity in work groups. In Diversity in Work Teams; Jackson, S.E., Ruderman, M.N., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mor Barak, M.E.; Cherin, D.A.; Berkman, S. Organizational and personal dimensions in diversity climate: Ethnic and gender differences in employee perceptions. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1998, 34, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D.; Glozer, S.; Spence, L.J. Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarso, E.; Bolisani, E. Trust-building mechanisms for the provision of knowledge-intensive business services. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 9, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Liechti, O.; Sumi, Y. Awareness and the WWW. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2002, 56, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieizadeh, K.; Tao, C.W.W. How does a menu’s information about local food affect restaurant selection? The roles of corporate social responsibility, transparency, and trust. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, L.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Ruggieri, R.; Gorelova, I. Is buying local food a sustainable practice? A scoping review of consumers’ preference for local food. Sustainability 2022, 14, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, J.; Prandota, A.; Rejman, K.; Halicka, E.; Tul-Krzyszczuk, A. Certification labels in shaping perception of food quality—Insights from Polish and Belgian urban consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, A.; Mesias, F.J.; Escribano, M. Perception of Spanish consumers towards environmentally friendly labelling in food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkoff-Zern, L.A. Race, immigration and the agrarian question: Farmworkers becoming farmers in the United States. J. Peasant Stud. 2018, 45, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Memery, J. Tourists, local food and the intention-behaviour gap. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Say Gouda, say cheese: Travel narratives of a food identity. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 22, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choe, J.Y.; Lee, S. How are food value video clips effective in promoting food tourism? Generation Y versus non-Generation Y. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.; King, B.; Mackenzie, M. Restaurant customers’ attitude toward sustainability and nutritional menu labels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 846–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S.S. Effects of restaurant green practices on brand equity formation: Do green practices really matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Questions |

|---|---|

| Deontological evaluation | Do you feel that restaurants have a responsibility to support minority farmers as part of their broader social and ethical commitments? |

| How important is it to you that restaurants think about all their stakeholders, like minority farmers, when deciding where to source their food? | |

| How important is it to you that restaurants share the benefits of supporting minority farmers with their customers? | |

| Teleological evaluation- Personal consequences | Does your trust in a restaurant increase when you know they have strong, transparent relationships with local minority farmers? |

| How does a restaurant’s involvement in its community and social networks influence where you choose to dine? | |

| Does knowing that a restaurant has long-term, trust-based relationships with minority farmers make you more confident about the safety and quality of the food? | |

| Would learning more about a minority farmer’s cultural practices and farming methods through the restaurant make you more likely to eat there? | |

| How does the idea of supporting minority farmers influence your dining choices? | |

| Teleological evaluation- Social consequences | How does a restaurant’s involvement in its community and social networks influence where you choose to dine? |

| How do you balance your appreciation for cultural diversity with your expectations for food safety and quality at restaurants? |

| Frequency (n) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 6 | 40 |

| Female | 9 | 60 |

| Age | ||

| 19–29 | 1 | 6.7 |

| 30–44 | 6 | 40 |

| 45–60 | 4 | 26.7 |

| 61 or older | 4 | 26.7 |

| Education level | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 9 | 66.7 |

| Master’s degree | 4 | 26.7 |

| Doctoral degree | 1 | 6.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 12 | 80 |

| Asian | 3 | 20 |

| Household income (annually) | ||

| ≤USD 50,000 | 2 | 13.3 |

| USD 50,001–USD 80,000 | 3 | 20 |

| ≥USD 100,000 | 9 | 60 |

| Prefer not to disclose | 1 | 6.7 |

| Frequency of dining out at a restaurant | ||

| Frequently (3 or more times per week) | 7 | 46.7 |

| Occasionally (1–2 times per month) | 6 | 40 |

| Monthly (1–4 times per month) | 2 | 13.3 |

| Frequency of making purchases from farmers markets | ||

| Frequently (1–3 times per week) | 4 | 26.7 |

| Occasionally (1–3 times per month) | 6 | 40 |

| Infrequently (1–3 times per year) | 2 | 13.3 |

| Rarely (more than 3 times per year but not monthly) | 1 | 6.7 |

| Never | 2 | 13.3 |

| Frequency of making purchases from minority farmers | ||

| Frequently (1–3 times per week) | 3 | 20 |

| Occasionally (1–3 times per month) | 4 | 26.7 |

| Infrequently (1–3 times per year) | 2 | 13.3 |

| Rarely (more than 3 times per year but not monthly) | 1 | 6.7 |

| Never | 5 | 33.3 |

| Beliefs | Example Quotation |

|---|---|

| Deontological Evaluations | |

| Community-Oriented Social Values | |

| Social responsibility (n = 15) | “I think the restaurant has the responsibility to support the minority farmers because it’s showing that they care about the community. (P1)” |

| Community support (n =13) | “I think it makes the restaurant more appealing that they are supporting the local people. (P7)” |

| Community connection (n = 9) | “The restaurant should be supporting the local farmers…I just think it’s important because of the community and keeping out community together and close. (P7)” |

| Reciprocity (n = 4) | “I know that I’m helping the restaurant local owner. I’m helping the local farmers. I’m also giving back to my local area, so I think it’s very important. (P4)” |

| Cultural Identity | |

| Cultural practices and farming methods (n = 12) | “I’m always interested in learning different cultures and different ways of doing things. (P4)” |

| Diversity and inclusion (n = 11) | “So for me, I appreciate the cultural diversity that a restaurant incorporates or is involved in. (P1)” |

| Perception of minority farmers (n = 11) | “I think it’s important for all businesses to do what they can to support, certainly, you know their neighbors…but especially those people (minority farmers) who, for various reasons, have been historically disadvantaged. (P9)” |

| Ethical concerns (n = 2) | “What is the real benefit for those minority farmers? Do they really get fair treatment from the restaurant? (P1)” |

| Teleological Evaluations | |

| Consumer Values−Food-Oriented | |

| Quality (n = 15), Taste (n = 7), Health (n = 6), Product specification (n = 4), Authenticity (n = 1) | “Well, I mean… I’m still, you know, I want fresh food. Yeah, I don’t want stuff that’s been prepared and just sitting over here. (P10)” |

| Sustainability (n =12) | “I’ve seen their farms… their farm is pristine… it’s beautiful, and you know it’s organic. (P7)” |

| Consumer Values−People-Oriented | |

| Preference, Appreciation (n = 10) | “Again, any local farm or anything sourced locally—like, it would pretty dramatically persuade me to choose them. (P3)” |

| Financial support (n = 9) | “Because I know that I’m supporting the local economy. (P4)” |

| Trust-Building Mechanisms | |

| Labels and regulation (n = 5), Food safety (n =14), Transparency (n = 15) | “Things like health department inspections and licenses, things like that… there’s always that assumption that the farmers put a lot of time and effort into producing safe products, then the restaurant can use production practices and deliver me a meal that’s safe. (P9)” |

| Advertising (n = 13), Storytelling (n = 4) | “Social media has been a big thing. So it is kind of information getting… out there to the younger generation… that a lot of restaurants cater to. This younger generation getting that kind of information to them would really help. (P15)” |

| Barriers | |

| Awareness (n = 14) | “I don’t really, we have to think. What restaurants in the Joplin area actually qualify (restaurants sourcing minority farmers’ produce). I don’t know. (P11)” |

| Price, Location, Distance (n =10) | “I know that they (restaurants) have to consider price, distance, and location, and stuff like that. (P6)” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, L.-P.; Liu, P.; Zhu, Q. Ethical Perceptions and Trust in Green Dining: A Qualitative Case Study of Consumers in Missouri, USA. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6493. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146493

Lin L-P, Liu P, Zhu Q. Ethical Perceptions and Trust in Green Dining: A Qualitative Case Study of Consumers in Missouri, USA. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6493. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146493

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Lu-Ping, Pei Liu, and Qianni Zhu. 2025. "Ethical Perceptions and Trust in Green Dining: A Qualitative Case Study of Consumers in Missouri, USA" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6493. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146493

APA StyleLin, L.-P., Liu, P., & Zhu, Q. (2025). Ethical Perceptions and Trust in Green Dining: A Qualitative Case Study of Consumers in Missouri, USA. Sustainability, 17(14), 6493. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146493

_Li.png)