Abstract

This study investigates the relationships between entrepreneurial leadership skills (ELSs), ethical entrepreneurial leadership (EEL), corporate sustainable development (CSD), and competitive advantage (CA) in SMEs. Drawing on resource-based view theory, we examine whether entrepreneurial capabilities and ethical practices jointly contribute to sustainability and competitive positioning. Data from 312 SME leaders across manufacturing, services, technology, and trading sectors were analyzed using PLS-SEM. Results reveal that ELSs foster EEL (β = 0.684, p < 0.001) and enhance CSD (β = 0.453, p < 0.001). EEL significantly affects CSD (β = 0.527, p < 0.001) and partially mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial skills and sustainability (indirect effect = 0.361). CSD strongly enhances CA (β = 0.612, p < 0.001). The findings demonstrate that integrating entrepreneurial capabilities with ethical leadership creates foundations for sustainable development and CA in resource-constrained environments. This research extends entrepreneurial leadership theory by showing complementarity between entrepreneurial and ethical orientations, advances sustainability theory by revealing ethical leadership’s mediating role, and enriches RBV by demonstrating how intangible leadership capabilities generate CA when traditional resources are scarce. Practical implications include developing integrated leadership programs and sustainability frameworks for emerging economy SMEs.

1. Introduction

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) constitute the backbone of Jordan’s economy, representing over 98% of all registered businesses and contributing approximately 40% to the country’s GDP while employing nearly 60% of the private sector workforce [1,2]. Globally, micro- and small-sized enterprises play a key role in developing emerging countries’ economies, representing more than 95% of registered businesses worldwide and contributing significantly to national income (over 35%) and employment (near to 50%) in the developing world [3]. These enterprises serve as crucial catalysts for job creation, poverty reduction, and economic development, particularly vital in developing countries like Jordan [4,5]. Moreover, SMEs provide essential economic flexibility, dynamism, and innovation capacity during periods of environmental turbulence, making them critical foundations for economic resilience and adaptive capacity in emerging economies [3]. However, Jordan’s unique contextual challenges significantly impact SME sustainability and survival. The modern business landscape increasingly demands the integration of sustainable practices and ethical leadership as fundamental drivers of organizational success and longevity [6]. Organizations worldwide are recognizing that sustainable development and ethical conduct are no longer optional but essential for maintaining competitive advantage (CA) and stakeholder trust [7,8]. This paradigm shift has become particularly critical in emerging economies where businesses must balance rapid growth aspirations with responsible practices [9]. Ethical practices encompass business policies and behaviors guided by principles of integrity, transparency, fairness, and social responsibility that consider the welfare of all stakeholders [10]. Jordan has pursued ambitious economic modernization through initiatives like Vision 2025, emphasizing entrepreneurship and sustainable development as key pillars of economic transformation [11]. Nevertheless, Jordanian SMEs continue to experience alarmingly high failure rates, with studies indicating that approximately 70% of SMEs fail within their first five years of operation, a challenge primarily attributed to the lack of sustainable practices and ethical leadership frameworks adapted to the local context [12,13,14].

The severity of this challenge is exacerbated by Jordan’s resource-constrained environment. The country faces severe resource scarcity, ranking as the second most water-scarce country globally, while also grappling with limited energy resources that result in high operational costs for businesses [15,16]. These resource constraints are compounded by pressing economic pressures including unemployment rates exceeding 23% and the ongoing challenge of integrating over 1.3 million Syrian refugees, which has strained infrastructure and intensified competition for limited resources [2,17]. Such conditions make sustainable business practices not merely desirable but critical for SME survival and growth. The inability of SMEs to adopt ethical leadership and sustainable practices in this challenging environment not only threatens individual business survival but also undermines Jordan’s broader economic development goals and its ability to attract international partnerships that increasingly demand Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) compliance.

Entrepreneurial leadership frameworks have emerged as promising approaches for enhancing SME performance, emphasizing innovation, risk-taking, and opportunity recognition as key drivers of business success [18]. These frameworks suggest that entrepreneurial leaders who demonstrate creativity, passion, and analytical thinking can better navigate competitive markets and drive organizational growth. Concurrently, corporate sustainability models focusing on the triple bottom line—balancing economic, social, and environmental performance—have gained traction as essential for long-term business viability [19]. Additionally, ethics-based leadership approaches have been shown to foster organizational integrity, enhance stakeholder trust, and improve overall performance [20]. These frameworks provide valuable insights but often lack contextualization for resource-constrained environments like Jordan.

To address the complex challenges facing Jordanian SMEs, researchers have investigated various dimensions of entrepreneurship and sustainability in this unique context. Recent studies identified persistent barriers including limited access to finance, inadequate digital transformation capabilities, and insufficient managerial competencies hindering SME growth [21]. Jordanian SMEs demonstrate innovation potential but exhibit conservative risk-taking behaviors due to political instability and resource constraints [22]. Traditional leadership approaches prevalent in family-owned businesses often clash with contemporary requirements for ethical governance and sustainable practices [23]. Moreover, environmental and social responsibility initiatives remain nascent among Jordanian SMEs, constrained by limited resources and insufficient awareness of sustainability benefits [24]. While these studies illuminate specific challenges, they reveal a critical gap in understanding the mechanisms through which Jordanian SMEs can simultaneously achieve entrepreneurial success and sustainable development within their resource-constrained environment. This raises a fundamental question for both researchers and practitioners:

How can Jordanian SMEs integrate entrepreneurial leadership with ethical practices to achieve sustainable competitive advantage in a resource-constrained environment?

This intersection reveals a critical void: while entrepreneurial and ethical leadership are recognized as essential for SME success, no existing framework demonstrates how Jordanian SME leaders can balance these with sustainability imperatives in their resource-constrained environment [25,26]. This gap is particularly urgent given Jordan’s Vision 2025 emphasis on sustainable entrepreneurship, increasing ESG requirements from international partners, and the lack of practical frameworks adapted to Jordan’s unique challenges [11].

To address this void, this study develops an integrated theoretical framework that explicates how entrepreneurial leadership skills (ELSs), when combined with ethical practices, can drive corporate sustainable development (CSD) and CA in Jordanian SMEs. This framework provides a practical roadmap for SME leaders to balance profit pressures with sustainability imperatives. The theoretical model is empirically validated through survey data collected from 312 SME leaders across Jordan, using structural equation modeling to test the proposed relationships and demonstrate the framework’s real-world applicability.

This research contributes to the existing literature in three ways. First, it extends entrepreneurial leadership theory by demonstrating how entrepreneurial competencies can be integrated with ethical considerations in resource-constrained environments, specifically addressing the Jordan context. Second, it advances corporate sustainability theory by revealing how ethical entrepreneurial leadership (EEL) serves as a critical mediator between entrepreneurial skills and sustainable development outcomes in developing economy SMEs. Third, it enriches the resource-based view by showing how the combination of entrepreneurial and ethical leadership capabilities creates sustainable CA even when traditional resources are scarce.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature and develops the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the methodology and data collection. Section 4 presents the empirical results and hypothesis testing. Section 5 discusses the findings, theoretical contributions, and practical implications. Section 6 concludes with limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Resource-Based View Theory

The resource-based view (RBV) is a managerial framework used to determine the strategic resources a firm can exploit to achieve sustainable CA [27,28]. Originally proposed by Wernerfelt (1984) [28] and later developed by Barney (1991) [27], RBV proposes that firms are heterogeneous because they possess heterogeneous resources, meaning that firms can adopt differing strategies because they have different resource mixes. A major premise of the resource-based theory is that CA is a function of the resources and capabilities of the firm [27], shifting focus from external industry structure to internal firm resources as the primary source of sustained CA.

For resources to hold potential as sources of sustainable CA, they should be valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable and organized (VRIO criteria) [27]. The VRIO framework asks four critical questions: (1) Is this resource valuable to the firm? (2) Is control of the resource limited? (3) Is there a significant cost disadvantage to obtaining or developing the resource? (4) Is the firm organized to exploit the resource? [27] Resources are valuable if they help organizations increase the value offered to customers by increasing differentiation or decreasing production costs [27]. Rarity occurs when a firm has a valuable resource that is unique among current and potential competitors, while imitability refers to whether there is a significant cost disadvantage for competitors to obtain or develop similar resources.

The resource-based theory seems to fit well the needs of owners and executives of SMEs [29], particularly in resource-constrained environments where traditional competitive strategies may be limited. For SMEs, RBV highlights the process toward achieving sustainable CA and offers insight into how different resources operate within smaller organizational contexts. The RBV approach helps firms understand how to achieve and sustain CA through resource building as well as leveraging existing resources, where a firm is viewed as a bundle of resources and routines that influence growth [27]. This theoretical lens is particularly relevant for understanding how SMEs can leverage their unique combination of ELSs, ethical practices, and sustainability initiatives to create CAs that larger competitors cannot easily replicate.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Leadership Skills

The dynamic and complex global business environment of the 21st century necessitates leadership approaches that move beyond traditional hierarchical structures and command-and-control management styles [30].

Drawing upon both management and entrepreneurship theories, researchers propose a multi-faceted understanding of entrepreneurial leadership. Kuratko and Hornsby [18] define it as a style of leadership that incorporates skills to enable employees to take the initiative and create innovative solutions to business problems. As such, scholars have identified several leadership skills that are important for ethical leadership, and as such there are several skills that an entrepreneurial leader must possess. Among these are (1) creativity [31], (2) risk taking [32], (3) innovativeness [33], and (4) passion and motivation [34].

Ethical leadership acts as a guide in organizations to increase ethical behavior and decision-making [10]. It is important for any individual that will lead the organization to become honest, have integrity, and be transparent during the process of making decisions [35,36]. Therefore, ethical leadership can positively affect organizational decisions.

Furthermore, entrepreneurial leaders show ethical conduct, meaning, their actions are honest, truthful, and trustworthy [37]. This honesty and trustworthiness are communicated not only through words but also through actions [38]. Through their ethical conduct, entrepreneurial leaders send a powerful signal to their followers, establishing a culture of integrity within the organization [39]. Therefore, I hypothesize the following:

H1.

Entrepreneurial leadership skills foster ethical entrepreneurial leadership.

2.3. Ethical Entrepreneurial Leadership

While entrepreneurial leadership emphasizes innovation and value creation, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential for unethical behavior in pursuit of these goals [40]. Ethical leadership serves as a critical foundation, ensuring that entrepreneurial endeavors are guided by principles of integrity, fairness, and social responsibility [10]. EEL goes beyond mere compliance; it involves proactively integrating ethical values into organizational culture and decision-making processes [41].

EEL has not always been of much importance, but given that customers, employees, and other stakeholders are expecting this kind of leadership, this theory has emerged [42]. As such, researchers have identified several components in ethical leadership. These components include (1) fairness [43], (2) morality [44], and (3) responsibility [27].

The visionary and proactive characteristics of entrepreneurial leaders make them adept at recognizing and capitalizing on opportunities to enhance CSD [45]. Entrepreneurial leadership, particularly within top management teams (TMTs), is widely recognized in the literature as a critical driver of a company’s global competitiveness [46,47,48]. These initiatives can enhance an organization’s CA by identifying and capitalizing on entrepreneurial opportunities that foster innovation and competitiveness [49].

Furthermore, innovative and creative mindsets enable entrepreneurial leaders to develop novel solutions to sustainability challenges, while their risk-taking propensity encourages them to experiment with uncharted strategies [50,51]. By embracing these entrepreneurial attributes, leaders create a conducive environment for CSD to flourish within their organizations, improving both internal and external success for business and community, and foster a culture of creativity and change to drive innovation and competitiveness [52]. The resource-based view (RBV) stresses the need for human and social capital for CA sustainability [53]. Consequently, I hypothesize the following:

H2.

Entrepreneurial leadership skills enhance corporate sustainable development.

2.4. Corporate Sustainable Development

In an increasingly resource-constrained and environmentally conscious world, CSD has become a strategic imperative for organizations seeking long-term viability and CA [28,54]. CSD encompasses the integration of environmental, social, and economic considerations into an organization’s business model and operational practices [55]. This holistic approach recognizes that businesses have a responsibility to minimize their negative impacts and contribute to the well-being of society and the environment [8].

A plethora of researchers have identified various concepts that are important when dealing with the topic of CSD. These consist of topics like (1) resource utilization [7], (2) environmental conservation [56], (3) long-term sustainability [57], (4) employee care [58], and (5) social governance [59].

As ethical leadership promotes honest business behavior and decisions, the organizations improve the engagement with their social activities. This leadership is often identified with entrepreneurial leadership [60]. This leadership is often identified with entrepreneurial leadership [60]. When a leader engages in proactive entrepreneurial behavior by optimizing risk, innovating to take advantage of opportunities, taking personal responsibility, and managing changes in the environment, this certainly has an impact on CA for businesses [61].

Therefore, improved operational efficiencies, reduced risks, and stronger stakeholder relationships directly contribute to CA [62]. For instance, leaders help employees to achieve a firm’s strategic goals, including utilizing CA [46]. Moreover, ethical leaders can help their company implement an organizational culture, knowledge sharing, and organizational innovation. They encourage change and create a setting that supports creativity and new ideas [63]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

Ethical entrepreneurial leadership promotes corporate sustainable development.

The mediation role of EEL in the relationship between ELSs and CSD finds theoretical support in social learning theory and stakeholder theory. Leaders serve as role models whose behaviors are observed and emulated by organizational members, suggesting that entrepreneurial skills alone may not directly translate into sustainable practices without the ethical framework that guides their application [64]. Ethical leadership provides the moral compass necessary to channel entrepreneurial capabilities toward socially responsible outcomes rather than purely profit-maximizing activities [65]. Furthermore, sustainable development requires balancing the interests of multiple stakeholders [66], which necessitates the ethical judgment and moral reasoning that EEL provides. Ethical leadership acts as a critical mechanism through which various leadership competencies are transformed into organizationally beneficial outcomes, particularly in contexts requiring long-term thinking and stakeholder consideration [67].

Empirical evidence supports the mediating role of EEL in driving sustainable development outcomes. Ethical leadership mediates the relationship between leader characteristics and organizational outcomes, particularly those related to social responsibility and environmental stewardship [68]. Ethical leadership serves as conduct through which entrepreneurial competencies are channeled toward sustainable business practices, as it provides the moral framework necessary for long-term value creation [69]. The mediation mechanism operates because entrepreneurial skills (such as innovation and risk-taking) require ethical guidance to ensure they are directed toward sustainable rather than exploitative opportunities [70]. Without EEL as a mediating mechanism, entrepreneurial skills may lead to short-term gains at the expense of long-term sustainability, whereas the integration of ethical considerations ensures that entrepreneurial capabilities are leveraged for sustainable development purposes [71]. Therefore, we conclude that EEL serves as a critical mechanism in the relationship between ELSs and CSD.

H4.

Ethical entrepreneurial leadership mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership skills and corporate sustainable development.

2.5. Competitive Advantage

In the context of increasing global competition and rapidly changing markets, CA remains a central objective for businesses striving to achieve long-term success [72]. CA refers to an organization’s ability to create superior value for its customers relative to its competitors, leading to increased market share, profitability, and overall performance [73]. The resource-based view (RBV) suggests that a firm’s unique resources and capabilities are the primary drivers of CA [28]. The RBV framework emphasizes the importance of developing and leveraging distinctive competencies that are difficult for competitors to imitate [74].

Several researchers have found the competitive edge through various methods. These methods to achieve the edge in an organization can be found below: (1) customer retention [75], (2) product innovation [76], (3) cost leadership [77], and (4) operational efficiency [78].

By implementing the principles and components of CSD, a company can create a CA for the business and get the business to differentiate their products or services [79]. The RBV stresses the need for human and social capital for CA sustainability [53].

Leaders help employees to achieve a firm’s strategic goals, including utilizing CA [46]. Leaders in the manufacturing sector are also looking for entrepreneurs who can manage the integration of innovative ideas into a complicated manufacturing system [80]. Furthermore, rapid innovation, as seen in the speed of introducing new goods, facilitates agile adaptation to changing conditions, reducing time and costs and ultimately enhancing overall organizational performance [47]. Consequently, the following is hypothesized:

H5.

Corporate sustainable development enhances competitive advantage.

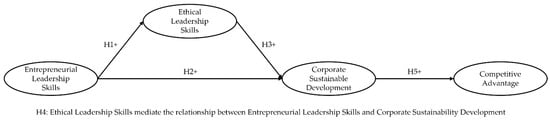

2.6. Proposed Research Model

The resource-based view theory provides the theoretical foundation for understanding how the four constructs in our model interact to create sustainable CA in resource-constrained environments. As illustrated in Figure 1, ELSs serve as the foundational resource capability that triggers a cascading process of value creation. The RBV framework explains how these skills, being rare and difficult to imitate, enable SME leaders to develop EEL practices (H1) while simultaneously driving CSD initiatives (H2). The theory further elucidates how EEL acts as a critical mechanism that enhances CSD (H3), with this ethical leadership serving as a mediator in the relationship between ELSs and CSD (H4). Finally, the integrated model demonstrates how CSD, as the culmination of resource orchestration where combined entrepreneurial and ethical capabilities are leveraged, generates CA for the organization (H5). This theoretical lens reveals how RBV theory supports the sequential and interconnected nature of these relationships, showing that sustainable CA emerges not from isolated resources, but from the dynamic interaction and integration of entrepreneurial skills, ethical practices, and sustainability initiatives that ultimately drive superior organizational performance within the same theoretical framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership skills, ethical entrepreneurial leadership, corporate sustainable development, and competitive sources: developed by the author based on the literature review.

3. Research Method

This study targeted SMEs operating in Jordan, defined as enterprises employing between 10 and 250 employees according to international standards. The sample frame consisted of registered SMEs in the Amman Chamber of Industry database. Using stratified random sampling, 750 SMEs were selected from various sectors to ensure representative coverage across different industries. The final sample comprised 312 responses from SME leaders (CEOs and senior managers), representing a response rate of 41.6%. This response rate aligns with academic standards, as research indicates that the average online survey response rate in published studies is 44.1% [81], and response rates between 40 and 75% are considered acceptable across different disciplines [82].

To ensure the validity and reliability of measurements, a structured questionnaire was developed based on validated scales from previous research. ELSs were measured using items adapted from Razzaque et al. (2024) [83], including dimensions of innovation (5 items), creativity (4 items), analytical thinking (4 items), emotional intelligence (5 items), and passion and motivation (4 items). EEL was measured using 6 items adapted from Sarmawa et al. (2020) [84], while CSD was assessed using 7 items from Ercantan et al. (2024) [85]. CA was measured using 5 items from Farhan (2024) [86]. All items utilized a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) to capture the intensity of responses. The complete list of measurement items and their sources is provided in Appendix A (Table A1).

Data collection occurred between February 2024 and September 2024 using the Qualtrics platform to facilitate online survey administration. Initial invitation emails were sent to SME leaders identified through the sampling frame, followed by two reminder emails at one-month intervals to maximize response rates. To minimize common method bias, a temporal separation strategy was employed whereby the collection of independent and dependent variables was separated by a two-week time lag. This approach helps reduce the potential for same-source bias that could inflate correlations between constructs.

The collected data were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS 4.1.0.9 software. This analytical approach was selected due to its suitability for complex models with multiple constructs and its predictive research objectives, particularly when dealing with relatively smaller sample sizes compared to covariance-based SEM techniques [87]. PLS-SEM also provides robust results when normality assumptions may be violated and is well-suited for exploratory research contexts like the current study.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Analysis of the sample demographics reveals important characteristics of both the respondents and their organizations. Among the 312 SME leaders who participated in the study, 68% were male and 32% were female. The age distribution shows that most leaders (66%) were between 30 and 49 years old, with a mean age of 42.3 years (SD = 8.7). Educational attainment was notably high, with 92.6% of respondents holding at least a bachelor’s degree, including 28.5% with master’s degrees and 7% with doctorates. In terms of leadership experience, 78.5% of respondents had five or more years of experience, with the largest group (39.7%) having 5–10 years of leadership experience.

Regarding organizational characteristics, the sampled SMEs displayed considerable variation in size and age. The average number of employees was 45.2 (SD = 23.8), with 45.5% of firms employing 26–50 people. The mean organizational age was 12.4 years (SD = 6.2), with 67.3% of firms operating for 5–15 years. The sample represented diverse industry sectors, with services (39.7%) and manufacturing (28.5%) comprising the largest segments, followed by technology (17.9%) and trading (13.8%). In terms of financial scale, half of the organizations (50%) reported annual revenues between JOD 1 and 5 million, while 25% reported revenues below JOD 1 million (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of sample characteristics (N = 312).

Table 2 provides a comprehensive breakdown of the specific industries represented within each major sector of the SME sample. The manufacturing sector encompasses traditional Jordanian industries such as textiles and garments (7.4%) and food processing (6.7%), alongside higher value-added activities including pharmaceuticals (5.8%) and chemical products (4.8%). Within the services sector, business consulting emerges as the most prominent industry (9.9%), followed by retail trade (9.0%) and tourism and hospitality (7.7%), reflecting Jordan’s growing service-oriented economy. The technology sector is primarily dominated by software development firms (8.0%), with telecommunications (5.8%) and IT services (4.2%) also well-represented. Finally, the trading sector consists mainly of import/export businesses (8.3%) and wholesale distribution companies (5.4%), highlighting Jordan’s strategic position as a regional trading hub. This diverse industry representation strengthens the generalizability of our findings across different business contexts and operational environments within the Jordanian SME landscape.

Table 2.

Detailed industry distribution of SME sample (N = 312).

4.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

The measurement model was evaluated through a comprehensive assessment of reliability and validity measures. The results, as shown in Table 3, demonstrate strong psychometric properties across all constructs and their dimensions.

Table 3.

Measurement model assessment—reliability and validity results.

Internal consistency reliability was established through both Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) values. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.867 to 0.912, well above the recommended threshold of 0.70 [88], indicating strong internal consistency. Similarly, composite reliability values ranged from 0.909 to 0.934, exceeding the critical value of 0.70 [87], further confirming the reliability of our measures.

Convergent validity was assessed through factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE). All factor loadings were statistically significant (p < 0.001) and ranged from 0.812 to 0.889, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.70 [87]. The lowest factor loading was observed for INNO3 (0.812), while the highest was recorded for ANTH2 (0.889). The AVE values for all constructions exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.50 [89], ranging from 0.665 for CSD to 0.739 for analytical thinking, demonstrating strong convergent validity.

For the ELS dimensions, innovativeness showed strong reliability (α = 0.892, CR = 0.921) with an AVE of 0.701. Creativity demonstrated similar robust properties (α = 0.874, CR = 0.913, AVE = 0.724), as did analytical thinking (α = 0.883, CR = 0.919, AVE = 0.739), emotional intelligence (α = 0.901, CR = 0.927, AVE = 0.718), and passion and motivation (α = 0.867, CR = 0.909, AVE = 0.714).

Discriminant validity was confirmed by comparing the square root of AVE values with inter-construct correlations [89]. The square root of AVE values (ranging from 0.815 to 0.860) exceeded the corresponding inter-construct correlations, providing evidence of discriminant validity.

The high t-values (ranging from 22.89 to 30.12) for all factor loadings further support the statistical significance of the measurement indicators. These results collectively indicate that our measurement model demonstrates strong reliability and validity, providing a solid foundation for testing the structural relationships hypothesized in our research model.

4.3. Structural Model Evaluation and Hypothesis Testing

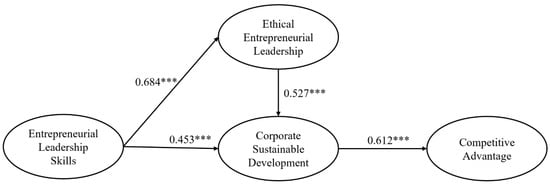

The structural model analysis, as summarized in Table 4, reveals significant relationships between the constructions under investigation. ELSs demonstrated a strong, positive association with EEL (β = 0.684, t = 18.456, p < 0.001), thereby supporting Hypothesis 1. This finding suggests that the development of entrepreneurial competencies—such as creativity, risk-taking propensity, and innovativeness—positively influences the ethical orientation of leaders within Jordanian SMEs. In other words, leaders who exhibit entrepreneurial traits are more likely to prioritize integrity, fairness, and social responsibility in their leadership approach.

Table 4.

Structural model results and hypothesis testing.

The relationship between ELSs and CSD was also found to be statistically significant (β = 0.453, t = 12.789, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2. This outcome implies that leaders with strong entrepreneurial skills are more inclined to integrate environmental, social, and economic considerations into their business models and operational practices. This emphasizes the role of proactive leadership in driving corporate sustainability initiatives.

EEL exhibited a positive and significant impact on CSD (β = 0.527, t = 14.234, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 3. This result reinforces the importance of ethical leadership in fostering sustainable business practices. SME leaders who prioritize integrity, transparency, and ethical decision-making are more likely to cultivate environmentally responsible policies, socially equitable practices, and economically viable strategies within their organizations (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results of structural model testing with standardized path coefficients. (Note: *** p < 0.001.)

To test Hypothesis 4, which proposed that EEL mediates the relationship between ELSs and CSD, a bootstrapping mediation analysis was conducted with 5000 bootstrap samples. The results revealed a significant indirect effect (β = 0.361, t = 11.892, p < 0.001) with a 95% bootstrap confidence interval of [0.298, 0.424] that does not include zero, supporting H4.

The mediation analysis indicates partial mediation, as the direct effect remained significant (β = 0.453) while the indirect effect accounted for 44.3% of the total relationship (VAF = 44.3%). This finding demonstrates that EEL serves as a critical mediating mechanism through which entrepreneurial skills are channeled toward sustainable development practices, while also confirming that entrepreneurial skills maintain a direct influence on CSD.

Ultimately, CSD demonstrated a significant and positive influence on CA (β = 0.612, t = 16.567, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 5. This finding indicates that SMEs that actively integrate sustainable development practices into their operations are better positioned to achieve a competitive edge. By implementing sustainable initiatives, organizations can improve their operational efficiency, reduce risks, strengthen stakeholder relationships, and ultimately differentiate themselves in the market.

Table 5 presents the effect sizes and explains variance for the endogenous constructs in the model. The R2 values indicate the amount of variance in each endogenous construct that is explained by its predictors. EEL had an R2 of 0.468, indicating that 46.8% of its variance was explained by ELSs. CSD had an R2 of 0.521, meaning that 52.1% of its variance was explained by ELSs and EEL. Finally, CA had an R2 of 0.454, indicating that 45.4% of its variance was explained by CSD. The adjusted R2 values are similar to the R2 values, taking into account the number of predictors in the model. The f2 values provide a measure of the effect size of each predictor on its respective endogenous construct.

Table 5.

Effect sizes and explained variance.

Table 6 displays the model fit indices, providing an assessment of the overall fit of the structural model. An SRMR below 0.08 is considered a great result. As such, the SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) value was 0.052, below 0.08, indicating a good fit between the model and the data. The NFI (Normed Fit Index) value was 0.912, exceeding the threshold of 0.90, further supporting the model fit. The Chi-square/df ratio was 2.345, below the threshold of 3.00, also indicating an acceptable model fit. These results collectively suggest that the structural model provides a reasonable representation of the relationships among the constructions.

Table 6.

Model fit indices.

Table 7 presents the total effects analysis, which decomposes the overall relationships between constructs into their direct and indirect components. The results reveal that ELSs exert their strongest total effect on CSD (0.814), with nearly half of this influence (0.361) operating indirectly through EEL. Notably, ELSs influence CA entirely through indirect pathways (0.498), emphasizing the critical mediating roles of ethical leadership and sustainable development practices in translating entrepreneurial capabilities into competitive outcomes. Table 7 presents the total effects analysis, which decomposes the overall relationships between constructs into their direct and indirect components. The results reveal that ELSs exert their strongest total effect on CSD (0.814), with nearly half of this influence (0.361) operating indirectly through EEL. Notably, ELSs influence CA entirely through indirect pathways (0.498), emphasizing the critical mediating roles of ethical leadership and sustainable development practices in translating entrepreneurial capabilities into competitive outcomes.

Table 7.

Total effects.

5. Findings and Discussion

This study examined relationships between ELSs, EEL, CSD, and CA within Jordanian SMEs. The first hypothesis (H1) proposed that ELSs foster EEL. This hypothesis was supported, indicating that leaders demonstrate creativity, innovativeness, analytical thinking, emotional intelligence, and passion engage in ethical leadership practices. This aligns with research emphasizing ethical leadership through honesty, integrity, fairness, and respect [90]. The relationship is significant given the MENA region’s emphasis on trust-based business relationships [91] and Generation Z’s demands for leadership ethics [92]. This contradicts concern that entrepreneurial orientation leads to unethical behavior, instead demonstrating enhanced capacity for ethical reasoning.

The second hypothesis (H2) posited that ELSs enhanced CSD. This was supported, confirming that entrepreneurial capabilities enable leaders to recognize sustainability opportunities. This supports insights emphasizing how entrepreneurial leadership creates mindsets focused on turning problems into economic and social value opportunities [93]. Within the MENA region, where only 14 Arab countries have achieved a single SDG goal [94], this relationship is critical. Jordan faces severe water scarcity and energy constraints, making entrepreneurial approaches essential, particularly as SMEs contribute 60–70% of global industrial emissions [95].

The third hypothesis (H3) suggested EEL promotes CSD. This was supported, demonstrating ethical considerations as fundamental sustainability drivers. This finding aligns with 2024 research showing that ethical leadership positively impacts employee behavior and organizational justice [96]. EEL provides moral frameworks for genuine stakeholder-focused sustainability initiatives, relevant as 2025 trends emphasize moving from goal setting to implementation [42,97].

The fourth hypothesis (H4) proposed that EEL mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial skills and sustainable development. This was supported, revealing that 44.3% of entrepreneurial skills’ influence on sustainability operates through ethical leadership pathways. This supports research indicating ethical leadership as a psychological mechanism shaping organizational outcomes [90]. This mediation is crucial where ethical leadership has become core for sustainable operations [95]. In Jordan’s cultural context, EEL ensures that innovative capabilities create inclusive value rather than exploitative practices, aligning with values-based leadership approaches [98].

The fifth hypothesis (H5) proposed CSD enhances CA. This was supported, confirming sustainability initiatives create tangible business value through enhanced brand reputation, cost savings, and customer loyalty [99]. Research shows “triple outperformers” on profit, growth, and ESG are twice as likely to achieve 10%+ revenue growth [100]. For SMEs in emerging economies, sustainability becomes essential for market access, as 84% report needing additional funding for emissions-reduction efforts [95].

The findings must be interpreted within Jordan’s cultural context, where business principles emphasizing stewardship and social responsibility strengthen alignment between entrepreneurial capabilities and ethical leadership [98]. The concept of public interest supports integrating sustainable development with CA. Jordan’s stakeholder-inclusive decision-making enhances ethical leadership’s mediating role [91]. Family-owned SMEs’ prevalence influences perceptions, as family businesses consider long-term perspectives and reputational impacts [94].

The sectoral diversity strengthens generalizability across manufacturing, services, technology, and trading firms facing distinct sustainability challenges, as SMEs increasingly adopt green practices driven by environmental concerns and business opportunities [101]. Organizational size variation demonstrates relationships hold across resource levels; significant given management commitment mediates sustainability drivers and environmental performance [101]. International and domestic market orientations validate findings regardless of market focus, though international exposure may amplify competitive advantages due to higher ESG expectations [102]. Generational diversity shows positive relationships reflect fundamental leadership principles rather than trends [103]. Jordan’s challenging economic environment strengthens findings by demonstrating that even under survival pressures, ethical entrepreneurial leaders pursue sustainable development, highlighting framework resilience as MENA poverty increased from 12.3% in 2010 to 18.1% in 2023 [94].

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes three distinct theoretical contributions that advance our understanding of entrepreneurial leadership, ethical leadership, and CSD. First, it extends entrepreneurial leadership theory by demonstrating how entrepreneurial competencies systematically integrate with ethical considerations rather than competing with them. Our findings reveal that entrepreneurial skills—creativity, innovativeness, analytical thinking, emotional intelligence, and passion—serve as antecedents to ethical leadership through three specific mechanisms: cognitive enhancement (analytical thinking enables better assessment of ethical implications), emotional competence (emotional intelligence facilitates stakeholder understanding), and motivational alignment (passion drives long-term value creation). This challenges the implicit assumption that entrepreneurial orientation and ethical behavior exist in tension, instead showing how entrepreneurial capabilities enhance leaders’ capacity for ethical reasoning, particularly relevant in resource-constrained environments where leaders must balance survival pressures with moral obligations.

Second, this research advances corporate sustainability theory by revealing how EEL serves as a critical mediating mechanism between entrepreneurial skills and sustainable development outcomes. The mediation analysis (β = 0.361, VAF = 44.3%) demonstrates that ethical leadership provides the “missing link”, explaining how leader characteristics translate into organizational sustainability outcomes through moral framing (channeling innovation toward sustainable opportunities), stakeholder integration (incorporating multiple perspectives in decision-making), and long-term orientation (moderating short-term profit focus). This contribution is particularly significant for developing economies, where ethical leadership ensures entrepreneurial capabilities serve broader societal goals rather than purely economic objectives, explicating the previously unclear psychological and behavioral mechanisms through which leadership drives sustainability initiatives.

Third, this study enriches the RBV by demonstrating how the combination of entrepreneurial and ethical leadership capabilities creates sustainable CA even when traditional resources are scarce. The integrated framework shows that sustainable CA (R2 = 0.454) emerges through resource orchestration (creating meta-capabilities for leveraging limited resources), dynamic capability development (continuously reconfiguring resources for sustainability challenges), and stakeholder resource access (ethical leadership enhances trust and partnerships that supplement resource constraints). This theoretical insight extends classical RBV beyond tangible resources to show how intangible leadership capabilities interact to create CA in resource-constrained contexts, providing a novel integrated framework that demonstrates how entrepreneurial leadership can be ethically grounded and sustainability-oriented for responsible business leadership in emerging markets.

5.2. Practical Implications

Based on the significant relationship between ELSs and EEL, Jordan’s policymakers should develop integrated leadership training programs that simultaneously build entrepreneurial competencies and ethical reasoning capabilities. Since EEL mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial skills and sustainable development, the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Supply should establish certification programs combining the five entrepreneurial dimensions (innovativeness, creativity, analytical thinking, emotional intelligence, and passion) with ethical decision-making frameworks, while creating incentive structures that reward SMEs demonstrating both entrepreneurial innovation and ethical governance practices.

For SME leaders, the strong relationship between EEL and CSD indicates that organizations must systematically integrate ethical considerations into their entrepreneurial activities. Leaders should develop the specific entrepreneurial skills identified in this research through innovation workshops, creative problem-solving sessions, and emotional intelligence training, while establishing ethical frameworks including stakeholder consultation mechanisms and transparency reporting systems. Since CSD significantly enhances CA, SMEs should prioritize sustainability initiatives encompassing resource utilization, environmental conservation, employee care, and social governance as identified in the research model.

To operate these findings, both policymakers and SME leaders need measurement and monitoring systems based on the validated constructions from this research. The Jordan Department of Statistics should develop assessment frameworks that measure the five entrepreneurial leadership dimensions, and six ethical leadership components identified in this study, enabling systematic tracking of SME leadership development and its impact on sustainability and competitive outcomes. Professional development programs should focus on the specific relationships demonstrated in the research: building entrepreneurial skills as a foundation for ethical leadership, using ethical leadership as a pathway to sustainability, and leveraging sustainability for CA. Implementation should follow the sequential model validated in this research, where entrepreneurial skill development leads to enhanced ethical leadership capacity, which then drives sustainable development practices that ultimately create CA. Success should be measured using the same constructs and relationships established in this study, with regular assessments of leadership capabilities, ethical practices, sustainability performance, and competitive positioning to ensure evidence-based policy and management decisions.

6. Conclusions

This research makes unique theoretical and practical contributions by developing and validating an integrated framework that demonstrates how ELSs, when channeled through EEL, drive CSD and CA in resource-constrained environments. The study’s unique theoretical contribution lies in revealing the mediating role of EEL, which bridges the gap between entrepreneurial capabilities and sustainability outcomes—a relationship previously unexplored in developing economy contexts. Practically, this research provides Jordan’s policymakers and SME leaders with an evidence-based roadmap for simultaneously pursuing economic success, ethical conduct, and environmental stewardship through specific leadership development strategies grounded in the validated five-dimensional entrepreneurial skills framework and six-component ethical leadership model.

Several limitations affect the validity and generalizability of these findings. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference validity and restricts generalizability to longitudinal contexts where leadership development evolves over time. The single-country focus on Jordan constrains external validity and generalizability to other cultural and economic contexts, particularly developed economies with different resource availability. Self-reported measures introduce common method bias concerns that may inflate correlations, affect construct validity and limiting generalizability to multi-source assessment contexts. The focus on SMEs limits generalizability to larger enterprises with different leadership dynamics, while emphasis on formal leadership excludes informal leadership influences, restricting generalizability to organizations with distributed leadership structures.

Future research should employ longitudinal studies spanning 3–5 years to establish temporal causality, incorporating quarterly leadership assessments and annual sustainability measures. Qualitative research using in-depth interviews with ethical entrepreneurial leaders and employee focus groups can explore psychological mechanisms underlying the mediation effects. Cross-cultural comparative studies should test this framework across developing and developed economies to assess cultural boundary conditions. Future investigations should examine moderating variables including leader gender, organizational governance structures (family-owned versus professionally managed), industry characteristics, and environmental uncertainty levels. Mixed methods approaches combining surveys with case studies can provide deeper implementation insights, while experimental designs could test specific interventions for developing EEL capabilities.

Ultimately, this research demonstrates that sustainable competitive advantage in resource-constrained environments emerges through the systematic integration of entrepreneurial capabilities, ethical leadership practices, and sustainability initiatives, providing a foundation for responsible business leadership that balances economic prosperity with social and environmental stewardship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.; Methodology, T.A.; Software, T.A.; Validation, T.A.; Investigation, T.A.; Resources, S.P.; Data curation, S.P.; Writing—original draft, T.A.; Writing—review & editing, S.P.; Supervision, S.P.; Funding acquisition, T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia. Grant No. [KFU252317].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of King Faisal University (No. KFU-2025-ETHICS2805; date: 6 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement items and sources.

Table A1.

Measurement items and sources.

| Variables and Dimensions | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Leadership Skills | [83] | |

| Innovativeness | - Frequently try new ideas | |

| - Seeks novel solutions to problems | ||

| - Initiates innovative practices | ||

| - Experiments with new approaches | ||

| - Encourages innovative thinking | ||

| Creativity | - Generates original solutions | |

| - Thinks outside conventional boundaries | ||

| - Develops creative strategies | ||

| - Promotes creative problem-solving | ||

| Analytical Thinking | - Systematically analyzes issues | |

| - Makes data-driven decisions | ||

| - Evaluates alternatives thoroughly | ||

| - Demonstrates logical reasoning | ||

| Emotional Intelligence | - Understands others’ emotions | |

| - Manages your own emotions effectively | ||

| - Shows empathy in interactions | ||

| - Builds strong relationships | ||

| - Handles conflict constructively | ||

| Passion and Motivation | - Shows enthusiasm for work | |

| - Inspires team members | ||

| - Demonstrates strong commitment | ||

| - Maintains high energy levels | ||

| Ethical Entrepreneurial Leadership | - Acts with integrity | [84] |

| - Demonstrates transparency | ||

| - Shows concern for stakeholders | ||

| - Makes ethical decisions | ||

| - Promotes ethical conduct | ||

| - Takes responsibility for actions | ||

| Corporate Sustainable Development | - Implements sustainable practices | [85] |

| - Balances stakeholder interests | ||

| - Considers environmental impact | ||

| - Promotes social responsibility | ||

| - Ensures economic viability | ||

| - Develops long-term strategies | ||

| - Engages in sustainable innovation | ||

| Competitive Advantage | - Maintains market leadership | [86] |

| - Achieves cost efficiency | ||

| - Delivers superior quality | ||

| - Shows strong differentiation | ||

| - Demonstrates adaptability |

References

- Jordan Economic Monitor, Fall 2020: Navigating Through Continued Turbulence. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/jordan/publication/jordan-economic-monitor-fall-2020 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Jordan In Figure 2022—Department of Statistics. Available online: https://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/product/jordan-in-figure2022/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Alshebami, A.S. Crisis Management and Customer Adaptation: Pathways to Adaptive Capacity and Resilience in Micro- and Small-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor-Aishah, H.; Ahmad, N.H.; Thurasamy, R. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Sustainable Performance of Manufacturing SMEs in Malaysia: The Contingent Role of Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahrouq, M. Success Factors of Small and Medium Enterprises: The Case of Jordan. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. 2010, 13, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Mousaco, B.G. How Can Leaders Change the Future?: The Role of Corporate Leadership in Sustainable Transitions from a Consultancy Perspective. Master’s Thesis, Department of Economics, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, L.S. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C. Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries as an Emerging Field of Study. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical Leadership: A Social Learning Perspective for Construct Development and Testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan 2025: A National Vision and Strategy; Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation: Amman, Jordan, 2015.

- Al-Hyari, K.; Al-Weshah, G.; Alnsour, M. Barriers to Internationalisation in SMEs: Evidence from Jordan. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawadieh, Z.; Altinay, L.; Cetin, G.; Şimşek, D. The Interface between Hospitality and Tourism Entrepreneurship, Integration and Well-Being: A Study of Refugee Entrepreneurs. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jinini, D.K.; Dahiyat, S.E.; Bontis, N. Intellectual Capital, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Technical Innovation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Knowl. Process Manag. 2019, 26, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Water Strategy 2022–2040. 2022. Available online: https://www.mwi.gov.jo/EBV4.0/Root_Storage/AR/EB_List_Page/national_water_strategy_2023-2040.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Alrawadieh, Z.; Alrawadieh, Z. Exploring Entrepreneurship in the Sharing Accommodation Sector: Empirical Evidence from a Developing Country. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan: Operational Update January 2023. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/fr/documents/details/103579 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Negeri, D.D.; Wakijira, G.G.; Kant, S. Meta Analysis of Entrepreneurial Skill and Entrepreneurial Motivation On Business Performance: Mediating Role Of Strategic Leadership In Sme Sector Of Ethiopia. Int. J. Mark. Digit. Creat. 2023, 1, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Corbo, L.; Caputo, A. Fintech and SMEs Sustainable Business Models: Reflections and Considerations for a Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, G.J.; Hartnell, C.A.; Leroy, H. Taking Stock of Moral Approaches to Leadership: An Integrative Review of Ethical, Authentic, and Servant Leadership. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 1, 148–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatila, K.; Nigam, N.; Mbarek, S. Seeds of Change: Nurturing Entrepreneurial Ecosystems for Sustainable Enterprises in Lebanon and Jordan. J. Entrep. 2024, 33, 897–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Shboul, M.A. Better Understanding of Executive Managers’ Features Effect on Small- and Medium-Sized Service Firms’ Risk-Taking Using Multiple Factors as Control Variables: Fresh Insights from Emerging Markets. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2327100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, O. Ethical Leadership and Sustainable Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises in South Africa. J. Glob. Bus. Technol. 2020, 16, 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhasoneh, O.M.; Jamaludin, H.; Zahari, A.R.B.; Al-Sharafi, M.A. Web-Based Social Networks as an Enabler for Sustainable Growth in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A PLS-SEM Approach. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Mirshak, R. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Theory and Practice in a Developing Country Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.; Paul, S.; Burnard, K. Entrepreneurial Leadership in Retail Pharmacy: Developing Economy Perspective. J. Workplace Learn. 2016, 28, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangone, A. A Resource-Based Approach to Strategy Analysis in Small-Medium Sized Enterprises. Small Bus. Econ. 1999, 12, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Marion, R.; McKelvey, B. Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting Leadership from the Industrial Age to the Knowledge Era. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghely, I.P.; Julien, P.A. Are Opportunities Recognized or Constructed?: An Information Perspective on Entrepreneurial Opportunity Identification. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M. The Proactive Personality Scale as a Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intention. Management 1996, 34, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The Promise of Enterpreneurship as a Field of Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Wincent, J.; Singh, J.; Drnovsek, M. The Nature and Experience of Entrepreneurial Passion. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebe, L.; Laura, T.; Hartman, P.; Brown, M. Moral Person and Moral Manager: How Executives Develop A Reputation For Ethical Leadership. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Maak, T.; Pless, N.M. Ethics: The Heart of Leadership. In Responsible Leadership; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2005; pp. 17–32. ISBN 9780203002247. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, G.; Luu, T.T.; Du, T.; Nguyen, T.T. Can Both Entrepreneurial and Ethical Leadership Shape Employees’ Service Innovative Behavior? J. Serv. Mark. 2023, 37, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Khatoon, A.; Cheema, A.U.; Ashraf, Y. How Does Ethical Leadership Enhance Employee Work Engagement? The Roles of Trust in Leader and Harmonious Work Passion. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 2090–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; Musa, S. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Leadership on Innovation Management and Its Measurement Validation. Int. J. Innov. Sc. 2017, 9, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; Brown, M.E. Managing to Be Ethical: Debunking Five Business Ethics Myths. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2004, 18, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; General Learning Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, L.; Lund, H.F. S&P Global’s Top 10 Sustainability Trends to Watch in 2025|S&P Global. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/esg/insights/2025-esg-trends (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Greenleaf, R.K. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness; Paulist Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Sendjaya, S.; Sarros, J.C.; Santora, J.C. Defining and Measuring Servant Leadership Behaviour in Organizations. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Millar, V.E. How Information Gives You Competitive Advantage Harvard Business Review. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1985, 60, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Leitch, C.M.; Volery, T. Entrepreneurial Leadership: Insights and Directions. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hsu, C.H.C. Linking Customer-Employee Exchange and Employee Innovative Behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 56, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, C.M.; Harrison, R.T. The Evolving Field of Entrepreneurial Leadership: An Overview; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781783473762. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V.; MacMillan, I.C.; Surie, G. Entrepreneurial Leadership: Developing and Measuring a Cross-Cultural Construct. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, H.; Gustafsson, A.; Witell, L. Competitive Advantage through Service Differentiation by Manufacturing Companies. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, D.V.R.; Tripathy, A. Innovation through Intrapreneurship: The Road Less Travelled. Vikalpa 2006, 31, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palalic, R. The Phenomenon of Entrepreneurial Leadership in Gazelles and Mice: A Qualitative Study from Bosnia and Herzegovina. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 13, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, M. Discourse Structure and Discourse Interpretation. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities And Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Roy, M.-J. Sustainability in Action: Identifying and Measuring the Key Performance Drivers. Long. Range Plann 2001, 34, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the s Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multilevel Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; Allen, D.B. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Value Creation among Large Firms: Lessons from the Spanish Experience. Long. Range Plann 2007, 40, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Business Performance: Effect of Organizational Innovation and Environmental Dynamism. South. Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 8, 348–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilke, O. On the Contingent Value of Dynamic Capabilities for Competitive Advantage: The Nonlinear Moderating Effect of Environmental Dynamism. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L. Value, Rareness, Competitive Advantage, and Performance: A Conceptual-Level Empirical Investigation of the Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiercz, P.M.; Lydon, S.R. Entrepreneurial Leadership in High Tech Firms: A Field Study. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2002, 23, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhi, W.; Fang, Y. Ethical Leadership, Organizational Learning, and Corporate ESG Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 98, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Islam, T.; Sadiq, M.; Kaleem, A. Promoting Green Behavior through Ethical Leadership: A Model of Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Knowledge. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Phillips, R.; Sisodia, R. Tensions in Stakeholder Theory. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mahmood, M.; Uddin, M.A.; Biswas, S.R. Ethical Leadership for Better Sustainable Performance: Role of Employee Values, Behavior and Ethical Climate. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhadra, W.A.; Khawaldeh, S.; Aldehayyat, J. Relationship of Ethical Leadership, Organizational Culture, Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Performance: A Test of Two Mediation Models. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2023, 39, 737–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S. Effects of Key Leadership Determinants on Business Sustainability in Entrepreneurial Enterprises. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 15, 885–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, H. The Impact of Ethical Leadership on Employees’ Green Innovation Behavior: A Mediating-Moderating Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 951861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Leadership Practices: Examine How Entrepreneurial Leaders Incorporate Sustainability into Their Business Models and the Leadership Traits Facilitating This Integration. J. Entrep. Bus. Ventur. 2025, 5, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Strategic Factor Markets: Expectations, Luck, and Business Strategy on JSTOR. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteraf, M.A. The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-based View. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J.H. Strategic Assets and Organizational Rent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utterback, J.M. Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 0-875-84342-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ghemawat, P. Sustainable Advantage. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1986, 64, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, M.A.; Keats, B.W.; DeMarie, S.M. Navigating in the New Competitive Landscape: Building Strategic Flexibility and Competitive Advantage in the 21st Century. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1998, 12, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.; Elangeswaran, C.; Wulfsberg, J. Industry 4.0 Implies Lean Manufacturing: Research Activities in Industry 4.0 Function as Enablers for Lean Manufacturing. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2016, 9, 811–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasi, H.; Fettke, P.; Kemper, H.G.; Feld, T.; Hoffmann, M. Industry 4.0. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2014, 6, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.J.; Zhao, K.; Fils-Aime, F. Response Rates of Online Surveys in Published Research: A Meta-Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 7, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sataloff, R.T.; Vontela, S. Response Rates in Survey Research. J. Voice 2021, 35, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, A.; Lee, I.; Mangalaraj, G. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Leadership Traits on Corporate Sustainable Development and Firm Performance: A Resource-Based View. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2024, 36, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmawa, I.W.G.; Widyani, A.A.D.; Sugianingrat, I.A.P.W.; Martini, I.A.O. Ethical Entrepreneurial Leadership and Organizational Trust for Organizational Sustainability. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1818368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercantan, K.; Eyupoglu, Ş.Z.; Ercantan, Ö. The Entrepreneurial Leadership, Innovative Behaviour, and Competitive Advantage Relationship in Manufacturing Companies: A Key to Manufactural Development and Sustainable Business. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2407V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, B.Y. Visionary Leadership and Innovative Mindset for Sustainable Business Development: Case Studies and Practical Applications. Res. Glob. 2024, 8, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaidan, H. Ethical Leadership in Action: Understanding the Mechanism of Organizational Justice and Leaders’ Moral Identity. Hum. Sys Manag. 2025, 44, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, A.A.; Sarif, S.M.; Ismail, Y. Islamic Leadership for Sustainability: A Systematic Literature Review Using PRISMA. OJIMF 2022, 2, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, V. What Is Ethical Leadership and Why Is It Important? Available online: https://professional.dce.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-ethical-leadership-and-why-is-it-important/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Mitchel, H. Entrepreneurial Leadership: A Complete Guide for 2025. Available online: https://www.edstellar.com/blog/entrepreneurial-leadership (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Abulenein, H. SDIM24: Driving MENA’s Sustainable Development Goal Progress|World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/09/mena-middle-east-north-africa-progress-sdg-sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Unlocking Opportunities for the Green Transition of SMEs. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/blog/unlocking-opportunities-green-transition-smes (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ughulu, J. Ethical Leadership in Modern Organizations: Navigating Complexity and Promoting Integrity. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2024, 08, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E. Sustainable Corporate Social Responsibility in 2025 vs. 2024. Available online: https://www.winssolutions.org/corporate-social-responsibility-csr/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Fisher Thornton, L. Ethical Leadership Development: Preparing Leaders For the Future—Leading in Context. Available online: https://leadingincontext.com/2024/03/06/ethical-leadership-development-preparing-leaders-for-the-future/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Sustainability as a Competitive Advantage. Available online: https://theintactone.com/2025/03/12/sustainability-as-a-competitive-advantage/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Fendri, M.; Lefevre, A.; Zhong, X. SMEs Should Link Growth with Environmental Sustainability|World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/09/net-zero-environmental-sustainability-smes-benefits/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Madrid-Guijarro, A.; Duréndez, A. Sustainable Development Barriers and Pressures in SMEs: The Mediating Effect of Management Commitment to Environmental Practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keelson, S.A.; Cúg, J.; Amoah, J.; Petráková, Z.; Addo, J.O.; Jibril, A.B. The Influence of Market Competition on SMEs’ Performance in Emerging Economies: Does Process Innovation Moderate the Relationship? Economies 2024, 12, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Gambetta, N. Technology-Driven Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2025, 35, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).