The Role of Organizers in Advancing Sustainable Sport Tourism: Insights from Small-Scale Running Events in Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Small-Scale Sport Events and Sustainable Tourism Development

2.2. Organizer Perceptions and Attitude in Tourism

2.3. The Growth of Running Events in Greece

3. Materials and Methods

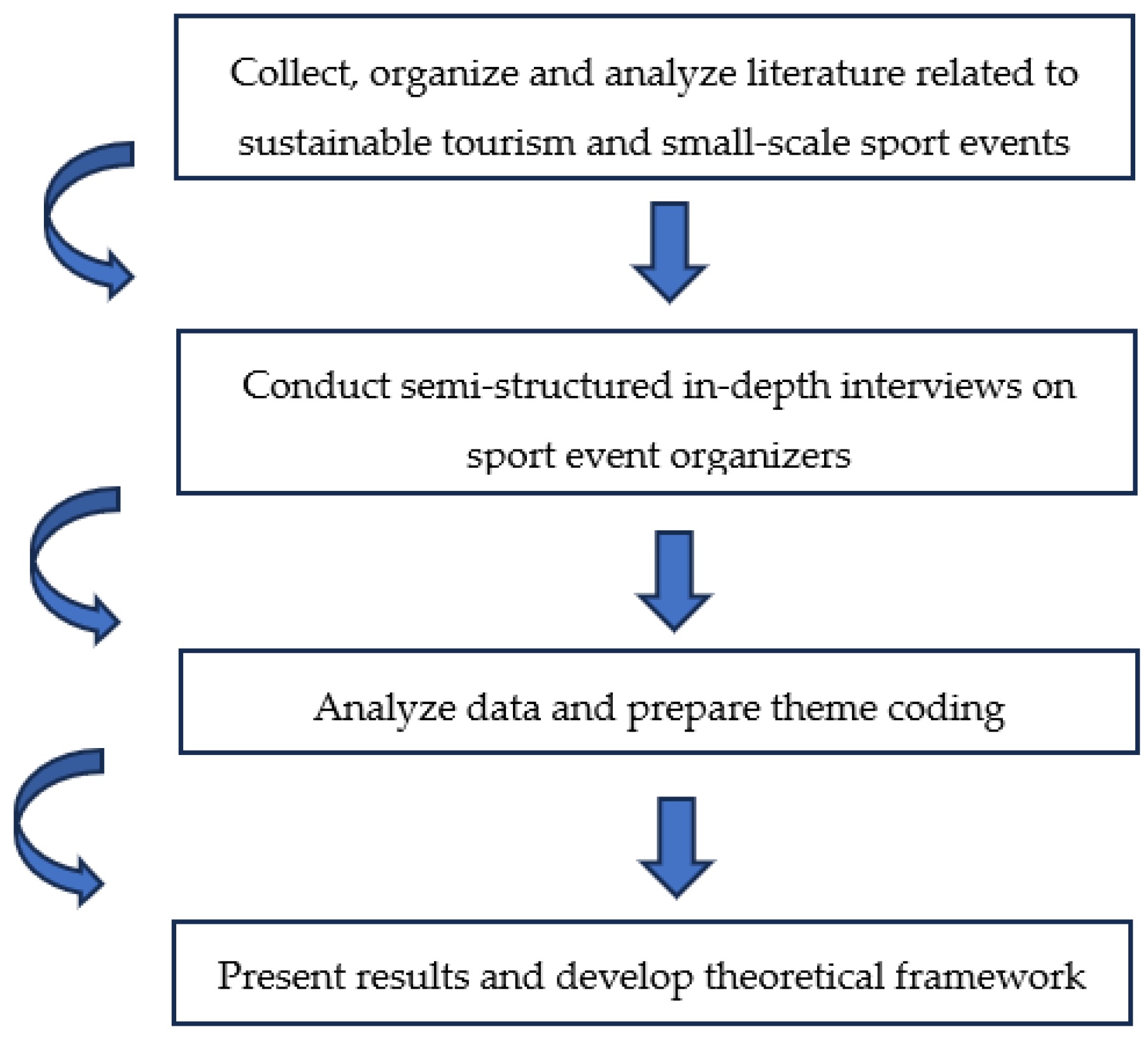

3.1. Research Procedure

3.2. Qualitative Research

3.3. Study Location

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

3.5.1. Open Coding

3.5.2. Axial Coding

3.5.3. Selective Coding

4. Findings

4.1. Economic Impact

“The economic effect is only positive for local businesses. They open at least three weeks earlier than they had planned in order to serve the athletes and their escorts. Consequently, the tourism season starts earlier because they do not close again. Also, if the weather is fine, there are visitors during the weekends”, Organizer 2.

“The economic impact is significant. People from 38 different countries visit us and they stay for more days after the event ends”, Organizer 4.

“The running event significantly contributes to the economic boost of the region. Apart from the race days, when hotels are full of visitors, athletes frequently come here for training. Some stay at hotels while others set up their own tents. As long as the race continues to exist, more athletes and their families will come during other seasons, not just for the race”, Organizer 5.

“Hosting, for example, a two-day running event, can significantly benefit the local economy. Many visitors would come to our island, including parents with their children, athletes, and spectators. They will certainly have coffee or lunch”, Organizer 9.

“We should bear in mind that the financial footprint of the event benefits the local economy. Because, as you understand (and this happens for every event, not just ours), during most events, the local community receives the financial benefits. There is very little income from sports activity for the organizers”, Organizer 12.

“The event results in a large number of visitors to the area. It is an important advertisement, and every year we see even more visitors who may initially come for the race but then return with their families for a vacation. This has a significant impact on businesses and their revenue. The event takes place before the beginning of the tourist season, and it serves as a test for businesses to ensure that they are ready in terms of staff and facilities before the peak tourist season”, Organizer 14.

“Certainly, our race is a kind of “injection” for the local economy. The increased tourist presence contributes to the extension of the tourist season and has a positive impact on the income of the locals, strengthening their finances for the rest of the year. The race financially affects the community to a great extent, as it is organized during an off-season weekend when local entrepreneurs do not expect to work because they are already closed. Therefore, it is an extra and very important income for them, ensuring a positive economic closure for the winter. In addition, jobs are created or existing employment contracts are extended with extra workforce in order to provide better services to visitors who come to the island” Organizer 1.

“During the days of the event, many local professionals hire extra staff to meet their needs”, Organizer 23.

4.2. Socio-Cultural Impact

“Society definitely comes closer thanks to the running event because everyone works and collaborates, I dare to say, voluntarily, in order to get the best possible result and a strong image of our island to the public”, Organizer 1.

“The impact on society is greater than the economic impact. Participation in our race can be done individually, but most run as groups. In fact, they usually train as a team weeks before the race. This is how relationships develop among the individuals in a group. However, relationships between residents and visitors cannot be cultivated in just one day”, Organizer 7.

“Sports generally help people. Through the race, relationships are strengthened”, Organizer 13.

“The race engaged locals who showed interest and decided to participate. Thus, we achieved our first goal: to involve all locals and attract people from other regions”, Organizer 19.

“In our small communities, events like our race are celebrations. Many people gather in our village, creating a very pleasant and festive atmosphere. The entire village meets in the square for the start and finish, watches the awards and the whole local community participates”, Organizer 24.

In addition, these events inspire the local youth and highlight the importance of sporting.

“Some people have taken up running thanks to the event. In this remote but beautiful region something unique is being implemented”, Organizer 13.

“From the very first race we held, 2–3 people began running. Sometimes, imitation is a positive phenomenon. Anyone who gradually develops a running consciousness is a benefit to society”, Organizer 22.

“Because the local community is involved, volunteers, along with women and elderly ladies, prepare local delicacies. Therefore, they are working together, and are active citizens of our society. This event brings something new to our region, which makes them happy.”, Organizer 8.

“Local associations prepare traditional food and showcase the culinary heritage of our region. This provides a wonderful opportunity for every athlete and visitor to experience the unique flavors of our region”, Organizer 25.

Inclusivity

“While the events are popular, they are not accessible to everyone. Older residents and people with disabilities often find it difficult to participate or even spectate”, Organizer 5.

“Almost all residents of all ages help, support or applaud the athletes. The race is their top event of the year. In this context, with full resident and local society support, social cohesion, cooperation and communication among locals are achieved”, Organizer 13.

“The race successfully engaged locals who showed their interest and actively participated. Thus, we achieved our first goal: to involve all locals and attract people from other regions, fostering foster inclusivity, bringing together people from different backgrounds and creating a welcoming atmosphere for all participants”, Organizer 19.

“The event unites people from diverse cultures. People from other cities and countries gather, increasing social contacts and locals learn how to provide services”, Organizer 21.

4.3. Environmental Impact

“As an organization, in cooperation with the sponsors, we use environmentally friendly materials to enhance the environmental awareness of participants”, Organizer 1.

“Athletes are people who are environmentally conscious. Events of this nature do not burden the environment through noise and garbage, so they are not an environmental burden; on the contrary, thanks to the events, the paths are maintained every year and then a beautiful well-worked network of trails remains that can be used by hikers or just ordinary tourists”, Organizer 8.

“Although there is a mass influx of people in our island on race day, traffic congestion is not a major issue. To promote sustainable environmental behavior, we include leaflets in the athletes’ bags, aiming to prevent vandalism and other environmental concerns”, Organizer 9.

“We are very strict in this issue, and we always point up that if someone grows garbage in the route, they will be excluded from the race and will not be able to participate again”, Organizer 10.

“In my view, sports contribute to environmental awareness. Athletes try to keep the space clean. Beyond our specific race, sports broadly help us become better. We are committed to ensuring our events do not negatively impact the environment”, Organizer 15.

“We actively collaborate with the municipality to ensure the city’s cleanliness is maintained to a high standard after the race”, Organizer 16.

“There are no environmental problems. At the end of the race there is a service which cleans the whole space, and the environment remains as it was before. Occasionally, the event results in enhanced area cleanliness and road improvements. This motivates us to continually strive for betterment”, Organizer 17.

“Runners are also environmentalists. We instruct participants to maintain area cleanliness, and consequently, the environment is cleaner after the race”, Organizer 22.

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO]. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/envir_e/sust_dev_e.htm (accessed on 17 March 2025).[Green Version]

- Jiang, Y.; Lyu, C.; Chen, W.; Wen, J. Following mega sports events on social media impacts Gen Z travelers’ sports tourism intentions: The case of the 2022 Winter Olympic Games. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2025, 50, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Poczta, J. A small-scale event and a big impact—Is this relationship possible in the world of sport? The meaning of heritage sporting events for sustainable development of tourism—Experiences from Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwell, T.C.; Danzey-Bussell, L.A.; Shonk, D.J. Managing Sport Events; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Priporas, C.V.; Vassiliadis, C.A.; Stylos, N.; Fotiadis, A.K. The effect of sport tourists’ travel style, destination and event choices, and motivation on their involvement in small-scale sports events. Event Manag. 2018, 22, 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliadis, C.A.; Fotiadis, A. Different types of sport events. In Principles and Practices of Small-Scale Sport Event Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 20–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gkarane, S.; Gianni, M.; Vassiliadis, C. Running toward sustainability: Exploring off-peak destination resilience through a mixed-methods approach—The case of sporting events. Sustainability 2024, 16, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkarane, S.; Vassiliadis, C.A.; Gianni, M. Exploring professionals’ perceptions of tourism seasonality and sports events: A qualitative study of Kissavos Marathon Race. Enlightening Tour. A Pathmaking J. 2022, 12, 24–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Kim, K.; Uysal, M. Perceived impacts of festivals and special events by organizers: An extension and validation. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, R.; Van Rheenen, D.; Sobry, C. Sport Tourism Events and Local Sustainable Development: An Overview. In Small Scale Sport Tourism Events and Local Sustainable Development; Melo, R., Sobry, C., Van Rheenen, D., Eds.; Sports Economics, Management and Policy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rheenen, D.; Sobry, C.; Melo, R. Running Tourism and the Global Rise of Small Scale Sport Tourism Events. In Small Scale Sport Tourism Events and Local Sustainable Development; Melo, R., Sobry, C., Van Rheenen, D., Eds.; Sports Economics, Management and Policy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzanella, F.; Schnitzer, M.; Peters, M.; Bichler, B.F. The role of sports events in developing tourism destinations: A systematized review and future research agenda. J. Sport Tour. 2023, 27, 77–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poczta, J.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E. Modern running events in sustainable development—More than Just taking care of health and physical condition (Poznan Half Marathon Case Study). Sustainability 2018, 10, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L. Stakeholder participation in tourism destination planning another case of missing the point? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2009, 34, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maditinos, Z.; Vassiliadis, C.; Tzavlopoulos, Y.; Vassiliadis, S.A. Sports events and the COVID-19 pandemic: Assessing runners’ intentions for future participation in running events—Evidence from Greece. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J. Active sport tourism: Who participates? Leisure Stud. 1998, 17, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.; Hinch, T. Sport Tourism Development; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 84. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzanella, F.; Peters, M.; Schnitzer, M. The perceptions of stakeholders in small-scale sporting events. J. Convent. Event Tour. 2019, 20, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J.; Kaplanidou, K.; Kang, S.J. Small-scale event sport tourism: A case study in sustainable tourism. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J. Sport tourism destinations: Issues, opportunities and analysis. In Sport Tourism Destinations; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hautbois, C.; Djaballah, M.; Desbordes, M. The social impact of participative sporting events: A cluster analysis of marathon participants based on perceived benefits. Sport Soc. 2020, 23, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Camacho, D.; González-García, R.J.; Alonso-Dos-Santos, M. Social impact of a participative small-scale sporting event. Sport Bus. Manag. 2021, 11, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig-Lewis, N.; Collins, A.; McCullough, B.P. The game is on!–Sports (events) as a driving force for sustainability. In The Routledge Companion to Marketing and Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2025; pp. 331–345. [Google Scholar]

- Walo, M.; Bull, A.; Breen, H. Achieving economic benefits at local events: A case study of a local sports event. Fest. Manag. Event Tour. 1996, 4, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, R.; Sobry, C.; Van Rheenen, D. Conclusion: Current Trends in Small Scale Sport Tourism Events and Local Sustainable Development. A Comparative Approach. In Small Scale Sport Tourism Events and Local Sustainable Development; Melo, R., Sobry, C., Van Rheenen, D., Eds.; Sports Economics, Management and Policy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taks, M.; Chalip, L.; Green, B.C. Impacts and strategic outcomes from non-mega sport events for local communities. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Smith, A. Events and sustainability: Why making events more sustainable is not enough. In Events and Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Campillo-Sánchez, J.; Borrego-Balsalobre, F.J.; Díaz-Suárez, A.; Morales-Baños, V. Sports and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Review of Their Contribution to the SDGs and Public Health. Sustainability 2025, 17, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chersulich Tomino, A.; Perić, M.; Wise, N. Assessing and considering the wider impacts of sport-tourism events: A research agenda review of sustainability and strategic planning elements. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, M.; Đurkin, J.; Wise, N. Leveraging small-scale sport events: Challenges of organising, delivering and managing sustainable outcomes in rural communities, the case of Gorski Kotar, Croatia. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshimi, D.; Yamaguchi, S. Leveraging strategies of recurring non-mega sporting events for host community development: A multiple-case study approach. Sport Bus. Manag. 2023, 13, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Mascarenhas, M.; Pereira, E. Exploring strategic multi-leveraging of sport tourism events: An action-research study. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 32, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Gámez, G.; Fernández-Martínez, A.; Biscaia, R.; Nuviala, R. Measuring Green Practices in Sport: Development and Validation of a Scale. Sustainability 2024, 16, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hou, T.; Matsuoka, H. The impact of recurring non-mega sport events on residents’ support intention. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2025, 16, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa-Hernández, M.; Farías-Torbidoni, E.I.; Seguí-Urbaneja, J. Sustainable practices in the organization of sporting events in protected and unprotected natural areas: A scoping review. Manag. Sport Leis. 2024, 29, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Sinwald, A. Perceived impacts of special events by organizers: A qualitative approach. Int. J. Event Fest. Manag. 2016, 7, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Oshimi, D.; Derom, I. How do event organizers and stakeholders collaborate to achieve the event’s strategic objectives? Leveraging the Tour de Okinawa. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2024, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, D.; Radmann, A. Keeping distance? Adaptation strategies to the Covid-19 pandemic among sport event organizers in Sweden. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2023, 8, 594–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Kerwin, S.; Karadakis, K. Understanding sport event success: Exploring perceptions of sport event consumers and event providers. J. Sport Tour. 2013, 18, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.; Mascarenhas, M.; Flores, A.; Chalip, L.; Pires, G. Strategic leveraging: Evidences of small-scale sport events. Int. J. Event Fest. Manag. 2020, 11, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, D.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; De Ridder, L.; Willem, A. Who participates in running events? Socio-demographic characteristics, psychosocial factors and barriers as correlates of non-participation—A pilot study in Belgium. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Vallejo, A.M.; Albahari, A.; Año-Sanz, V.; Garrido-Moreno, A. What’s behind a marathon? process management in sports running events. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandris, K. Testing the role of sport event personality on the development of event involvement and loyalty: The case of mountain running races. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2016, 7, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutrou, N.; Kohe, G.Z. Sustainability, the Athens Marathon and Greece’s sport event sector: Lessons of resilience, social innovation and the urban commons. Sport Soc. 2025, 28, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, C.; Neale, P. Conducting In-Depth Interviews: A Guide for Designing and Conducting In-Depth Interviews for Evaluation Input, 2nd ed.; Pathfinder International: Watertown, MA, USA, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Fotiadis, A.; Stylos, N.; Vassiliadis, C.; Huan, T.C. Advocation travel: Choice of events amongst amateur (non-professional) participants involved in small-scale sporting events. In Proceedings of the Global Marketing Conference, Hong Kong, China, 21–24 July 2016; pp. 1516–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.; Moser, T. The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. Int. Manag. Rev. 2019, 15, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, H.J.; Willming, C.; Holdnak, A. Small-scale event sport tourism: Fans as tourists. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.C.; Mascarenhas, M.V.; Flores, A.J.; Pires, G.M. Nautical small-scale sports events portfolio: A strategic leveraging approach. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duglio, S.; Beltramo, R. Estimating the economic impacts of a small-scale sport tourism event: The case of the Italo-Swiss mountain trail CollonTrek. Sustainability 2017, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L. Towards social leverage of sport events. J. Sport Tour. 2006, 11, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchandani, G.; Davies, L.E.; Coleman, R.; Shibli, S.; Bingham, J. Limited or lasting legacy? The effect of non-mega sport event attendance on participation. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, B.G.; Shapiro, D.R. People with disabilities and sport: An exploration of topic inclusion in sport management. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 21, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Dickson, T.J.; Benson, A.M. London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Including volunteers with disabilities—A podium performance? Event Manag. 2014, 18, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.J.; Darcy, S.; Johns, R.; Pentifallo, C. Inclusive by design: Transformative services and sport-event accessibility. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 532–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.R.M.; Gallego, R.M.; Mas, J.R.L. Effects of an inclusive running event on children’s attitudes toward disability students in physical education. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2024, 1056–1065. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9557887 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, E.; Kim, S.K. Understanding active sport tourist behaviors in small-scale sports events: A stimulus-organism-response approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022. 2022. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

| Open Code | Categories | Concepts | Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|

| OC1 | Economic benefits | Increased local incomes | The road race positively affects our city. A large number of people come, they eat, they drink, they go from one place to another, they probably stay one night, and this means that 1000, 2000 or 5000€ come in the city. The more the events, the better for our community |

| (Organizer 10) |

| Axial Code | Categories | Concepts | Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC1 | Economic impact | Revenue increase | Local businesses, especially hotels and restaurants, increase their sales during the days of the race, Organizer 5 |

| Seasonality mitigation | Since the road race occurs during off-season period, it attracts tourists and provides a boost to our local economy, Organizer 7 | ||

| Indirect economic benefits | The road race puts our area in the map. It attracts visitors who discover our region and return for future visits, Organizer 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkarane, S.; Kavoura, A.; Vassiliadis, C.; Kotzaivazoglou, I.; Fragidis, G.; Vrana, V. The Role of Organizers in Advancing Sustainable Sport Tourism: Insights from Small-Scale Running Events in Greece. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146399

Gkarane S, Kavoura A, Vassiliadis C, Kotzaivazoglou I, Fragidis G, Vrana V. The Role of Organizers in Advancing Sustainable Sport Tourism: Insights from Small-Scale Running Events in Greece. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146399

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkarane, Sofia, Androniki Kavoura, Chris Vassiliadis, Iordanis Kotzaivazoglou, Garyfallos Fragidis, and Vasiliki Vrana. 2025. "The Role of Organizers in Advancing Sustainable Sport Tourism: Insights from Small-Scale Running Events in Greece" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146399

APA StyleGkarane, S., Kavoura, A., Vassiliadis, C., Kotzaivazoglou, I., Fragidis, G., & Vrana, V. (2025). The Role of Organizers in Advancing Sustainable Sport Tourism: Insights from Small-Scale Running Events in Greece. Sustainability, 17(14), 6399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146399

_Li.png)