Abstract

A university’s reputation is a key indicator of the quality of its education, the competitiveness of its alumni, its institutional influence in society, and its degree of global recognition, including its ranking and rating among higher education institutions (HEIs) around the world. This not only enhances institutional standing and secures positions in international rankings but also promotes sustainable education practices. In addition, students, their parents, and their partners select universities due to their trust in the reliability of a university’s public reputation and ranking. This study proposes a model to assess a university’s reputation based on specific factors. In this research, the dependent variable is university reputation, the mediating variable is university social responsibility, and the independent variables include the teacher reputation, alumni reputation, research and innovation, and cooperation. A survey of 5902 respondents—including alumni, employers, and parents—offers diverse perspectives on university reputation. Data were analyzed using structural equation modeling tools (Smart PLS 4.1 and SPSS 25.0). The findings confirm that social responsibility has a strong and positive influence on university reputation. Furthermore, faculty and alumni reputation, research and innovation, and external collaboration directly enhance universities’ social responsibility. This suggests that social responsibility serves as a key mediating variable in the relationship between institutional capacity and reputation. This study represents the first empirical assessment of university reputation in Mongolia, addressing a notable gap in the literature. By incorporating context-specific insights and stakeholder perspectives, the research offers both theoretical contributions and practical implications. The results provide a foundation for developing regionally responsive strategies to improve the quality of higher education and advance sustainable development goals.

1. Introduction

A critical aspect of ensuring the sustainable growth of a higher education institution (HEI) is its reputation. Reputation is a reflection of quality, and at the same time, the quality of education is one of the key goals of sustainable development. In recent years, educational institutions have been placing greater emphasis on strengthening their reputation at both the national and international levels. HEIs must carefully manage their reputation by focusing on the quality of their education, research, and community engagement while also responding to challenges that could undermine their public image. A strong reputation enables universities to thrive, attract top talent, and contribute positively to society [1]; it also allows them to recruit top research and teaching staff, improves financial and competitive performance, and increases media visibility and investment opportunities.

Recently, the Government of Mongolia has been actively implementing projects and programs aimed at aligning educational and training standards with international benchmarks [2]. For instance, the long-term strategic plan for sustainable development of the country includes the goal of improving the quality of universities by establishing their rankings and promoting their recognition internationally. As a part of this goal, it has become important to assess the reputation of universities via the participation of their external stakeholders, such as alumni, parents, and employers. In other words, alumni can determine the reputation of their own universities, parents can assess the institutions where their children study, and employers can evaluate the universities where their employees graduated from based on an institution’s professional behavior, career advantages, and overall competence. Additionally, under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Mongolia has set an objective to support at least four universities in achieving international rankings. University rankings are influenced not only by direct collaboration between the institution and ranking organizations but also by the assessments of other stakeholders [3].

Every university strives to improve its competitive standing in the education market, making it important to examine theories surrounding university reputation and the factors that affect it [4,5].

However, currently, there is a lack of clear policies or strategic frameworks on how to ensure sustainable development at the planning and operational level of universities, and there are no established indicators or criteria to evaluate it. This study aims to address that gap by identifying university reputation as a critical indicator of sustainable development, exploring the factors that influence it, and creating an evaluation model grounded in stakeholder input and participation.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify an important indicator of sustainable development, namely, university reputation, identify the factors affecting it, and develop an evaluation model based on stakeholder evaluation and participation. In order to achieve this goal, we addressed the following research questions (RQs):

- How can HEIs contribute to sustainable development through social responsibility?

- What factors influence the increase in university social responsibility?

- How does the social responsibility of an HEI affect a university’s reputation based on external stakeholder perspectives?

Organizational learning theory suggests that universities are perceived more favorably when they contribute to sustainable development and social welfare through effective knowledge transfer, which in turn boosts their reputation [6]. Furthermore, the achievements of university faculty and alumni directly enhance the reputation of the university [7,8]. Universities collaborate with various organizations and individuals to generate, share, and apply knowledge as well as to foster innovation—efforts that directly strengthen their reputation [9]. Evaluation factors for UR may encompass social responsibility, teacher and alumni reputation, research and innovation outcomes, and collaborative reputation [10,11]. This approach recognizes that HEIs engage in numerous socially oriented activities centered on knowledge creation and distribution. To accurately and comprehensively assess a UR, the involvement of multiple different stakeholders is essential [12,13]. In this study, we believe that employers, alumni, and parents can offer valuable perspectives on the university’s reputation. Alumni, for instance, can provide insightful feedback on the quality of education, acquired knowledge and skills, campus environment, faculty, and program content. Employers have firsthand knowledge of graduates’ workplace readiness. Parents, meanwhile, often have a strong understanding of the university’s societal impact, its community involvement, and their children’s capabilities and attitudes [14]. The research results suggest that universities should enhance their social responsibility, promote faculty achievements in teaching and research, and strengthen their activities in education, research, and community outreach to secure a stronger societal standing. HEIs, specifically, can foster numerous partnerships with faculty, staff, and students to further their social responsibility initiatives [15,16].

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

Higher education institutions (HEIs) build their reputation and demonstrate social responsibility through actions that reflect their value and quality. This approach can be explained through multiple theoretical lenses, including signaling theory, institutional theory, stakeholder theory, and corporate social responsibility (CSR). According to signaling theory [17], universities engage in actions that send credible signals to the external environment regarding their academic and social value. These signals include accreditation, international rankings, high-profile research output, and global partnerships, all of which shape stakeholder perceptions and institutional reputation. Institutional theory suggests that universities must align with socially accepted norms, values, and expectations to maintain legitimacy and survive in a competitive environment [18]. From this perspective, universities enhance their reputation not only through academic performance but also by conforming to institutionalized structures and behaviors, such as ethical conduct, environmental responsibility, and community engagement. Stakeholder theory [19] emphasizes that institutions must create value for multiple stakeholders beyond shareholders, such as students, parents, employers, policymakers, and society at large. Universities that meet the expectations of these diverse groups by offering inclusive education, employable graduates, and societal contributions tend to build strong reputational capital. CSR theory further posits that organizations, including universities, are responsible for contributing to the welfare of society through ethical, environmental, and social actions [20,21]. In this context, the level of university social responsibility (USR) is determined by how effectively the institution fulfills its commitments to its stakeholders, including teaching excellence, research relevance, sustainable practices, and community partnerships. Together, these theoretical perspectives frame the university reputation (UR) as a multifaceted construct influenced by performance, legitimacy, stakeholder trust, and perceived social value. HEIs have three core functions: teaching, research, and social service [22]. While international studies have explored these areas in various contexts, there remains a research gap in understanding how university reputation and social responsibility intersect in Mongolia. It appeared in the research that Mongolian higher education, perhaps focusing only on teaching and research, does not take sufficient action to fulfill the social responsibility obligations of universities and to assess and improve their social reputation [23].

2.1. University Reputation (UR)

Reputation is widely regarded as a long-term, external evaluation of an organization by third parties, which influences both strategic behavior and organizational identity [24]. In the context of HEIs, reputation serves as a critical indicator of educational quality and institutional effectiveness. University reputation (UR) is a fundamental indicator of a university’s quality and effectiveness. Therefore, it is more appropriate to base our research on institutional and stakeholder theories because these emphasize not only organizational performance but also the degree to which institutions gain acceptance from society. In HE, such prominence is often shaped by sustained performance, stakeholder trust, innovation output, and alignment with societal expectations. Stakeholders assess reputation based on multiple factors, such as the quality of graduates [25], faculty prestige [26], and the university’s contribution to innovation and technology transfer [27]. The reputation of a university can impacts student selection of the university [28], the knowledge held by stakeholders [29], the evaluation and rating of the university [9], and its research experience and teaching quality [30]. Consequently, it is important to understand the variables that contribute to reputation management of HEIs [31] because a reputation management framework grounded in institutional and stakeholder theories provides a comprehensive lens to explore how universities build and maintain legitimacy, visibility, and societal value.

2.2. University Social Responsibility (USR)

The role of the university social responsibility (USR) is the main strategic component in shaping institutional reputation. USR as a university’s commitment to recognizing the interests of society and performing in a way that improves the well-being of its members through the provision of quality educational services [32]. Universities that actively engage in social responsibility initiatives positively influence students’ perceptions of their reputation, highlighting the importance of USR in reputation management [33]. Institutional theory suggests that universities must align with socially accepted norms, values, and expectations to maintain legitimacy and survive in a competitive environment [18]. From this perspective, universities enhance their reputation not only through academic performance but also by conforming to institutionalized structures and behaviors, such as ethical conduct, environmental responsibility, and community engagement. Stakeholder theory [19] emphasizes that institutions must create value for multiple stakeholders beyond shareholders, such as students, parents, employers, policymakers, and society at large. Vasilescu [20] emphasizes that USR activities contribute to the overall performance and reputation of higher education institutions by fostering trust and credibility among stakeholders. In this context, the level of USR is determined by how effectively the institution fulfills its commitments to its stakeholders, including teaching excellence, research relevance, sustainable practices, and community partnerships. Together, these theoretical perspectives frame the UR as a multifaceted construct influenced by performance, legitimacy, stakeholder trust, and perceived social value. According to Bat-Erdene J. & Otgonbaatar B., Mongolian higher education institutions, perhaps focusing only on teaching and research, do not take sufficient action to fulfill the social responsibility obligations of universities and to assess and improve their social reputation [23]. Universities can make a meaningful contribution to the SDGs through the implementation of socially responsible initiatives.

2.3. Teacher Reputation (TR) and University Social Responsibility (USR)

Teacher reputation (TR) is a key indicator of the quality of an educational institution. The knowledge and expertise of teachers often influence parents and students in selecting a specific profession or school. The ability of teachers to support students in reaching their goals, combined with their accomplishments in teaching and research, is instrumental in shaping a university’s reputation [34]. Students’ perceptions of TR are measured in three main dimensions: teachers’ teaching methods and classroom management; teachers’ attitudes and personalities; and teachers’ performance and status in society [35]. From the perspective of reputation theory, a university’s reputation is not solely shaped by its institutional brand but is also strongly influenced by the professional image and recognition of its faculty members [36]. According to stakeholder theory, faculty members are considered the primary interface between the university and its key stakeholders. Students, parents, and alumni tend to interact more frequently with faculty than with institutional leadership, making teachers the most visible and influential representatives of the university [19,37]. Through this lens, the reputation of an institution is often shaped by the conduct, competence, and academic presence of its educators. Moreover, students are more inclined to enroll in institutions with reputable and high-performing faculty. Teachers’ professional achievements and research outputs often contribute substantially to societal development and innovation. Based on prior research, faculty reputation is not only crucial for academic excellence but also plays an integral role in strengthening the USR. By serving as role models and actively engaging in community-related activities, respected faculty members enhance the university’s social legitimacy and commitment to societal well-being [35,38].

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Teacher reputation has a positive effect on university social responsibility.

2.4. Alumni Reputation (AR) and University Social Responsibility (USR)

An important measure of a university’s educational efficacy is the knowledge and skills acquired by its graduates. In recent years, universities’ quality assurance criteria and ranking assessments have increasingly emphasized the achievements and contributions of their graduates, particularly in terms of academic excellence and research impact [39]. Within the ranking system, universities proactively manage their reputation by highlighting the accomplishments of their alumni. In higher education, the ranking and reputation of universities are determined by multiple factors, and the success of their graduates and students is an essential aspect. The time it takes for graduates to find employment after completing their studies and their career achievements serves as indicators of the quality of education offered by the university. Successful graduates enhance the reputation of their educational institutions [40,41]. In addition, parents choose a university for their children’s future education not only based on quality, location, and tuition fees but also on the success and career growth of its graduates. This is related to their children’s future professional success, and they believe that if a university’s graduates work at an advanced level and have an impact on society, the university will provide the same opportunities for future graduates. Fostering ongoing relationships with alumni and implementing collaborative programs that enable current students to learn from the success of their predecessors is a robust strategy for enhancing a university’s reputation [42,43]. This strategy improves the institution’s rankings and attracts top-tier students and faculty while expanding partnerships with industry.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Alumni reputation has a positive effect on university social responsibility.

2.5. Research and Innovation (R&I) and University Social Responsibility (USR)

Universities contribute to a nation’s social, economic, and technological advancement, ultimately strengthening its global standing [34]. The scope of the USR is multifaceted, including concepts such as providing equal and accessible higher education, supporting regional development, ensuring sustainable development, and enlightening the public. USR should be a fundamental strategic objective of the university rather than a routine activity organized for the good of society [44]. Thus, research output, innovative activities, and university social responsibility play a vital role in building a strong UR. According to the stakeholder theory [19], university R&I can create impact and value not only for students but also for professionals, industries, businesses, and partner organizations. In particular, R&I by academics and faculty fosters collaboration with social stakeholders.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The research and innovation of an HEI has a positive effect on its social responsibility.

2.6. Cooperation (CO) and University Social Responsibility (USR)

The joint initiatives of leading universities and their departments are essential in facilitating knowledge exchange and advancing research while also boosting the reputation of HEIs through innovation [45,46]. By strengthening partnerships with both domestic and international educational institutions, research organizations, and industries, universities can greatly elevate their reputation and contribute to creating tangible economic benefits. Moreover, cooperation between universities and industries establishes a framework for learning by offering workforce education and skills training. Involving learners in future workplace scenarios [47], with support from both academic faculty and business professionals [48], can enhance knowledge retention and foster skill development [49]. To enhance research and development activities and attract highly skilled professionals at the regional level, HEIs must strengthen their collaborative efforts with industry, government, and society. This involves establishing and co-creating collaborative laboratories that unite academia and enterprises to drive knowledge and technology transfer toward practical solutions. These efforts should target areas critical to enhancing the region’s or country’s innovative capacity [50]. Over the past few decades, fostering collaboration among leading universities has remained a considerable challenge. Researchers have focused on identifying the key factors for success, including attracting international students, preparing them for academic integration, and promoting interactions with foreign universities and educators [51].

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

University cooperation has a positive effect on university social responsibility.

2.7. University Social Responsibility (USR) and University Reputation (UR)

Universities serve as major influencers in society, and their commitment to social responsibility is essential for promoting societal development [52]. Universities that actively participate in local community development, such as providing educational programs, health services, and economic support, build strong, positive relationships with the community. The role of social responsibility (SR) in HEIs is not only restricted to the provision of education but also to attain a certain standard of performance that satisfies the emerging needs of the social setup [53]. The integration of SR into a university’s operations significantly bolsters its reputation. By committing to community engagement, sustainability, ethical governance, impactful research, and philanthropy, universities not only fulfill their moral and civic duties but also attract talent, secure funding, enhance public perception, and achieve higher rankings [54]. Social responsibility refers to context-specific organizational actions and policies that respond to stakeholder expectations and aim to generate economic, social, and environmental value [55].

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

University social responsibility has a positive effect on university reputation.

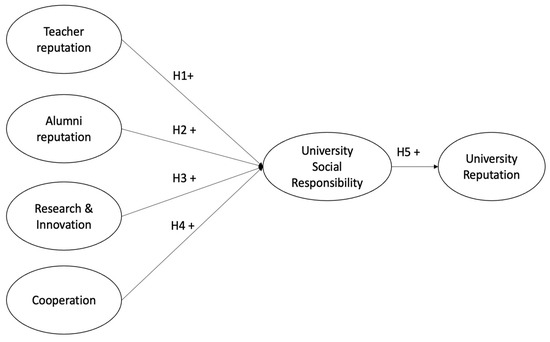

Based on the hypotheses and theories proposed by prior researchers [17,18,19,20,21], we identified the main factors that influence university social responsibility: teacher reputation, alumni reputation, research and innovation, and internal/external cooperation. For university stakeholders, the activities and outcomes of teaching and research are seen as the services and responsibilities the university provides to society. For instance, the professional contributions of teachers and alumni play a vital role in shaping society, organizations, individuals, and governments. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that reputable teachers and alumni enhance a university’s overall social responsibility. Furthermore, internal and external cooperation, along with innovative initiatives, are viewed as key factors of a university’s responsibility to society. By engaging in partnerships with industry, government, other academic institutions, and the broader public, universities can play an active role in addressing social and economic challenges. Based on this theoretical perspective, we present the following hypothetical model for our study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed model of university reputation.

3. Materials and Methods

Social sciences have relied on complex models that examine the relationships between observed and latent variables through covariance analysis for decades. However, in recent years, there has been a growing shift toward the use of the PLS-SEM (partial least squares structural equation modeling) approach, as highlighted by Hair et al. [56], because PLS-SEM provides the ability to analyze complex causal models and conduct path analysis. In addition, PLS-SEM is very suitable for exploratory research with secondary data, as it offers the flexibility needed for interplay between theory and data [57]. Akter et al. noted that most prior research on sample size requirements in PLS-SEM overlooked the fact that the method also proves valuable for analyzing large quantities [58]. Indirect stakeholders’ evaluation is important in assessing the quality of education. We used external stakeholders in our research to determine the UR. UR is a representation of how stakeholders—such as alumni, employers, and parents—evaluate a university. In Mongolia, there is limited research on this topic, and studies have yet to explore UR and USR through the perspective of these three stakeholders.

3.1. Measures

Our survey questionnaire contains six scales to measure AR, TR, R&I, CO, USR, and UR that were modified based on previous studies [59], taking into account the specific characteristics of the educational system in Mongolia. According to the hypotheses of this study, four independent variables were considered to affect UR through the mediating variable of USR. The participants of the survey included alumni, employers, and parents who were asked for their opinions about the four factors that influence the UR and USR. The questions were measured using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.2. Data Collection

A total of 66 higher education institutions (HEIs) are currently engaged in providing higher education in Mongolia. As part of efforts to rank Mongolian universities in line with Sustainable Development Goal 4, a university reputation survey was conducted for the first time, with evaluations based exclusively on input from external stakeholders. To ensure accessibility, inclusiveness, and reliability, the survey employed a convenience sampling method and was administered online via the platform https://high.eec.mn (accessed on 14 September 2023). Respondents included alumni, parents, and employers who were registered at the participating universities. The representation of parents was extended to include not only the student’s mother and father but also older siblings or guardians who are responsible for the student. This adjustment was made in consideration of the fact that herder families in rural areas often face challenges in accessing and participating in system-based surveys.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Respondents

The objective of gathering initial factual data on UR is to aggregate information from three targeted segments. This includes analyzing information related to UR and considering the factors influencing it. In this study, we used a preliminary model to gather data from stakeholders such as employers, alumni, and parents.

We structured the collection of data on UR and its factors by considering organizational reputation based on fundamental principles. These include the general responsibility of the institution, the reputation of its graduates and teachers, international and domestic collaborations, and academic research and innovation.

In Mongolia, there is a demand to gather data from three specific stakeholders’ groups and conduct an analysis of university reputation, as there has been no previous extensive research or analysis of data regarding university reputation. The sample size for this study was determined using a double random sampling approach. The data were collected through the academic affairs offices of higher education institutions, targeting their key stakeholders.

We collected the survey data in collaboration with the academic departments of higher education institutions, with their support in engaging key stakeholders. A stratified sampling method was employed, with sample sizes varying depending on the number of students, graduates, and employers at each institution. In total, 7240 responses were initially collected.

After filtering out incomplete and erroneous entries, 5902 valid responses were retained for the final analysis. These valid responses represented employers, graduates, and parents from 66 universities in Mongolia and included responses from 1903 graduates, 638 employers, and 3361 parents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Respondents’ characteristics.

4.2. Measurement Model

For the hypotheses proposed in this study, we assessed the measurement model by establishing the construct’s reliability and validity. In the measurement model analysis, construct reliability was established through Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). These two types of analysis were conducted using two main methods. First, a hypothetical model of university social responsibility and university reputation was estimated for all samples. Second, a comparative study was conducted for each group of alumni, employers, and parents using the hypothesized model. Table 2 presents a measurement analysis based on the raw data collected from 5902 study participants. Construct reliability and convergent validity for the complete sample are presented in Table 3. Cronbach’s Alpha values ranged from 0.750 to 0.916, AVE values ranged from 0.653 to 0.751, and CR values were from 0.857 to 0.929 by the constructs.

Table 2.

Construct reliability and validity by all samples.

Table 3.

Reliability and convergent validity.

Table 3 shows that the measurement model analysis results for the study participant groups are within acceptable ranges.

4.3. Validating Formative Construct

The validating formative construct is an important step in structural equation modeling (SEM) when constructs are formative. In this study, partial least squares structural equation modeling (Smart PLS, version 4.1) was used to analyze data [60]. To validate the constructs, first, multicollinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). If VIF values are less than or equal to 10, that indicates no multicollinearity [61]. There is no multicollinearity issue (Table 2 and Table 4).

Table 4.

Construct validation (university reputation).

4.4. Structural Model

After the analysis of the measurement model, a structural model analysis was performed through which we determined the direct relationships between the latent variables. In addition, the proposed hypotheses were tested. The results of this study show that all hypotheses are supported and statistically significant (Table 5 and Table 6). As can be concluded from Table 5, the results of the data for each group are consistent with the results of the total data. The results of each group from all samples are essentially consistent for the total sample.

Table 5.

Path coefficients by complete data.

Table 6.

Direct relationships by groups.

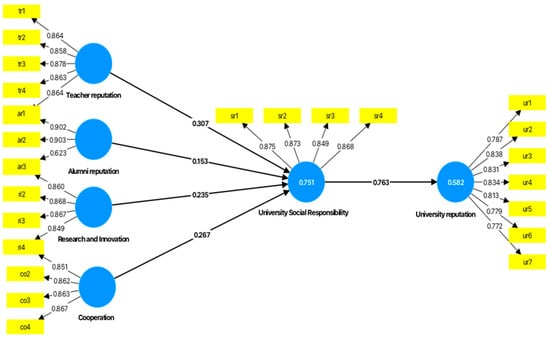

The analysis of the structural model estimated an R2 value of 0.75 for the university social reputation construct, indicating that 75% of the variance was university social responsibility. This indicates that the model fits well (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM algorithm results of the university reputation model (total sample).

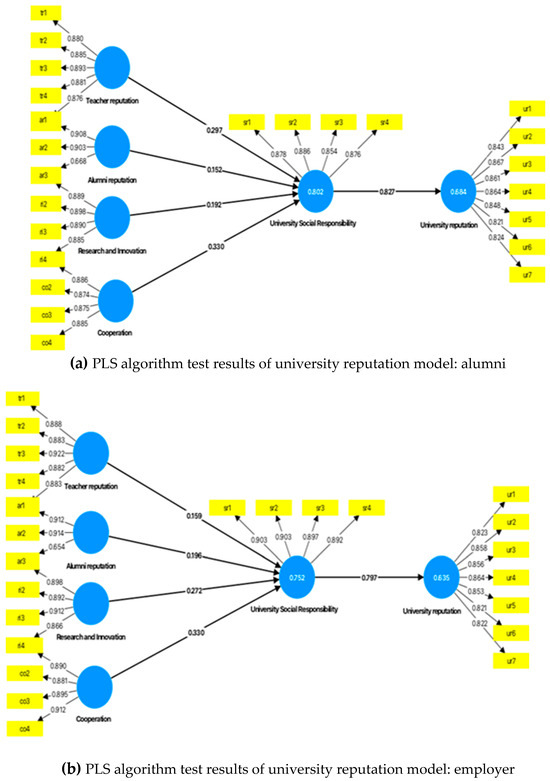

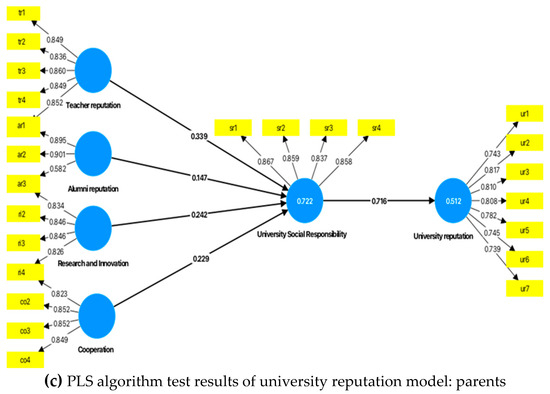

Based on the study results, we were able to answer the second research question as follows. For the total sample, the following factors showed a positive and statistically significant influence on university social responsibility (USR): teacher reputation (TR: β = 0.307), alumni reputation (AR: β = 0.153), research and innovation (R&I: β = 0.235), and cooperation (CO: β = 0.267). This finding was consistent across stakeholder groups: TR→USR (H1): alumni (β = 0.297), employers (β = 0.159), parents (β = 0.339). This suggests that graduates and parents have a closer relationship with teachers than employers and therefore perceive a stronger influence from teacher-related factors. AR→USR (H2): alumni (β = 0.152), employers (β = 0.196), parents (β = 0.147). The results show that administrative responsibility has a relatively similar level of influence across all stakeholder groups. R&I→USR (H3): alumni (β = 0.192), employers (β = 0.272), parents (β = 0.242). This indicates that research, development, and innovation activities have a stronger impact on employers and parents. It highlights the importance for universities to collaborate with industries and government bodies in order to boost their reputation and contribute more effectively to sustainable development. CO→USR (H4): alumni (β = 0.330), employers (β = 0.330), parents (β = 0.229). Internal and external collaboration is shown to be a significant factor for all stakeholders (Figure 3 a, b, c). Strengthening partnerships with domestic and international institutions, research centers, and industry players presents a valuable opportunity for universities to enhance their reputation and impact. In addition, the R-square values for each group (alumni, employers, and parents) are between 0.716 and 0.800 (Table 6). In addition, this study carried out a robustness check of the PLS-SEM model [62]. To evaluate the model’s predictive accuracy, we used the method introduced by Shmueli et al. [63], which applies PLS path modeling. Based on this approach, a PLS predict/CVAT analysis was conducted (Table 7). The results showed that both the coefficient of determination (R2) and the cross-validated predictive ability (Q2) were significantly greater than zero, suggesting that the proposed model demonstrates strong predictive capability.

Figure 3.

PLS algorithm test results of university reputation model.

Table 7.

PLS predict cross-validated predictive ability test (CVPAT) and coefficient of determination (R2).

4.5. Mediation Analysis

Mediation analysis was performed to assess the mediating role of USR in the relationship between independent variables and UR. The analysis confirmed the significant mediating role of USR between key factors (TR, AR, R&I, and CO) and UR across all stakeholder groups. All four hypotheses (H1–H4) were supported, with USR partially mediating the relationships significantly VAF (42–50%, p < 0.000), (Table 8).

Table 8.

Mediation analysis results.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the UR, which is an important factor in the sustainable development of HE. This study proposed two theoretical models. The first model proposed four hypotheses, H1–H4, which state that USR is influenced by the following factors: teacher reputation (H1), alumni reputation (H2), university research and innovation contributions to society (H3), and cooperation (H4). The second model was based on the hypothesis that the USR would increase the UR (H5). The results of this research showed that the above hypotheses were significantly supported by the structural measurement and structural models. This supports the research findings of Diana Escandon-Barbosa et al. [30,64] that the research experience, pedagogy, and quality of teachers affect the academic reputation of universities. In particular, USR is not measured solely by one-sided perceptions but rather by the participation of stakeholders in the institution. For example, research has been conducted on USR based on the perceptions of students and faculty [65,66,67]. This study highlights that universities that engage more in social responsibility initiatives tend to have better reputations. This is supported by the data showing that universities with higher USR scores also have a higher rank in reputation.

The structural model testing supported all five proposed hypotheses (H1–H5), demonstrating the significant role of university social responsibility (USR) both as a dependent and as a mediating construct. This effect was consistently strong across employers, alumni, and parents. This study concluded that both employers and alumni play a more substantial role in influencing USR. Overall, the R-squared value for the first model ranged from 0.716 to 0.800, indicating that AR, TR, CO, and R&I are all critical factors in enhancing social responsibility at universities.

This research shows that the main indicator of the sustainable development of higher education institutions is the reputation of the university, with SR serving as a critical factor in enhancing it. Parents prioritize the reputation of teachers and alumni, whereas employers focus on the university’s collaboration efforts and research innovation alongside alumni reputation. This analysis emphasizes that university administrators need to foster community-focused initiatives, promote faculty achievements, prioritize student learning outcomes and quality, and strengthen both internal and external cooperation and research innovation to address societal and organizational challenges. This study, grounded in institutional theory, signaling theory, and stakeholder theory, underscores the capacity of higher education institutions to actively contribute to sustainable development through the implementation of university social responsibility (RQ1). In particular, stakeholder and institutional theories are most compatible with university reputation research, as they demonstrate the need to focus on collaboratively implementing activities that meet the interests and needs of multiple stakeholders with whom universities are directly and indirectly involved.

The findings indicate that key drivers of USR include the scope and impact of research and innovation, the breadth of internal and external collaborations, and the social value created through faculty and alumni engagement (RQ2). These institutional factors shape how stakeholders assess a university’s social responsibility performance, which in turn significantly influences the university’s overall reputation (RQ3). Furthermore, it is crucial to highlight that this study goes beyond a single perspective by incorporating input from external stakeholders, including employers, alumni, and parents. This comprehensive approach results in more accurate and realistic conclusions.

The results of our research confirm that universities can increase their social standing and thereby enhance their reputation through the reputation of their teachers and alumni, the benefits of internal and external cooperation of the institution, and the research and innovation work of academics and researchers. Our study demonstrates that it is possible to systematically measure university reputation based on participatory evaluation of stakeholders and is characterized by the innovative use of PLS-SEM in the research methodology. Furthermore, it is important to establish basic evaluation indicators for assessing university reputation in order to determine the contribution of higher education institutions to the sustainable development of the country.

A limitation of this study is that it focuses solely on external stakeholders in examining UR. To address this, we suggest the following directions for future research: (1) Including both external and internal stakeholders of the university would offer a more comprehensive understanding of the UR and SR. (2) This study can be expanded by adding additional factors that influence USR, such as stakeholder satisfaction, relationship quality, university image, organizational culture, student reputation, values, and sustainable development indicators. (3) By considering the perspectives, evaluations, and feedback of stakeholders in HE, identifying and addressing their diverse needs, and applying these insights to university operations, the institution can enhance its contribution to sustainable development.

6. Conclusions

This study contributes to the theoretical understanding of how TR, AR, CO, R&I, USR, and UR value creation are perceived by external stakeholders, including employers, parents, and alumni. Although previous studies have examined UR and USR [30,64,68,69], few have employed structural equation modeling with active stakeholder involvement, highlighting a gap that this study addresses.

Structural equation modeling was employed in the UR study, with separate analyses conducted for both measurement and structural models. These analyses were performed for the overall survey results, encompassing employers, alumni, and parents, as well as for each group individually. Given the inclusion of USR as a mediating variable, a mediation analysis was conducted. The structural model analysis metrics, including Cronbach’s Alpha, CR, AVE, T-value, p-value, and R-square, demonstrated effectiveness.

Through education, academic training, and research, they contribute to social, economic, and environmental development, fulfilling their social responsibility [69,70]. This study highlights the importance of universities engaging with stakeholder perspectives and collaborating to effectively implement sustainable development policies and strategies. Additionally, it was stressed that administrators should prioritize enhancing social responsibility as well as fostering research, innovation, and collaboration in order to strengthen the position of their universities in society and enhance their reputation.

Based on these findings, several strategic recommendations are proposed to strengthen institutional engagement in reputation: first, universities should promote the application of academic research outcomes in industrial and societal contexts. Expanding international and domestic collaborations and engaging proactively in addressing social challenges can serve as key mechanisms to reinforce institutional legitimacy and social value. Second, building faculty research capacity and visibility is critical. Supporting academic leadership through continuous professional development and effective public communication may enhance the reputation of faculty members and increase the attractiveness of academic careers among students. Third, the adoption of key influencing factors as criteria for evaluating university reputation is recommended. These may include the following: teacher reputation (e.g., number of research publications, faculty with a high H-index, total citations), alumni reputation (e.g., employment rate, salary levels, job positions, career longevity), national and international collaboration (e.g., joint training and research projects, student exchanges, external funding), and socially driven innovations (e.g., solutions addressing social challenges, educational innovations, technological contributions, measurable social impact). Fourth, universities are encouraged to establish an institutional infrastructure such as a Sustainable Development Policy Unit that is dedicated to promoting quality education, stakeholder engagement, and long-term development strategies. Such a unit can facilitate alumni career support, improve graduate tracking systems, enhance community partnerships, and increase national and international collaboration.

As a long-term outcome, this center can serve as a strategic hub, aligning institutional policies with the SDGs, fostering citizen empowerment through knowledge dissemination, and advancing inclusive participation in societal development. As such, universities should be positioned not only as centers of knowledge production but also as active agents of social transformation and civic advancement through science, innovation, and public engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and supervision, C.R.; methodology and analysis, C.R. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.P., A.A., and C.R.; writing—review and editing, N.P., A.A., and C.R.; resources and data collection, N.P., G.-O.D., and T.L.; project administration, E.N. and P.N.; funding acquisition, H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by “Capacity Building Project for School of Information and Communication Technology at Mongolian University of Science and Technology in Mongolia (Contract No. P2019- 00124) funded by KOICA (Korea International Cooperation Agency).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Articles 12.9 and 12.4 of the Higher Education Law of Mongolia mandate that external evaluations of higher education institutions be conducted with the involvement of key stakeholders, including parents, alumni, and employees, as part of the national institutional ranking and classification process. This study aims to assess university reputation and the factors influencing it. The survey questionnaire was developed by researchers from the Research Institute for Educational Quality and was reviewed and approved by the Institute’s Ethics Board to ensure the protection of participants’ personal information and safety. The survey was classified as “risk-free”. The data collection was conducted in collaboration between the Education Evaluation Center, affiliated with the Ministry of Education and Science, and the Research Institute for Educational Quality (NGO) via online (https://high.eec.mn accessed on 14 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the survey. Consent was obtained electronically, and only those who agreed to the study conditions were able to proceed with the questionnaire via online (https://high.eec.mn accessed on 14 September 2023).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Ministry of Education and Science of Mongolia, the Research Institute of Educational Quality of Mongolia (NGO), and the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) for their support, as well as to all the participants who contributed to the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HEI | Higher Education Institution |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UR | University Reputation |

| USR | University Social Responsibility |

| TR | Teacher Reputation |

| AR | Alumni Reputation |

| R&I | Research and Innovation |

| CO | Cooperation |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SPPS | Partial least squares structural equation modeling |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Amado, M.; Acosta, F. Reputation in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Front. Educ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Overview Analysis of Educational Policy of Mongolia. 2019. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373687_mon.locale=en (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Brankovic, J.; Hamann, J.; Ringel, L. The institutionalization of rankings in higher education: Continuities, interdependencies, engagement. High. Educ. 2023, 86, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Villar, B.; Alcaide-Pulido, P.; Carbonero-Ruz, M. Measuring a University’s Image: Is Reputation an Influential Factor? Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshtaria, T.; Datuashvili, D.; Matin, A. The impact of brand equity dimensions on university reputation: An empirical study of Georgian higher education. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2020, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, H.; Drysdale, L.; Gurr, D. What We Know about Successful School Leadership from Australian Cases and an Open Systems Model of School Leadership. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safón, V. Inter-Ranking Reputational Effects: An Analysis of the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) and the Times Higher Education World University Rankings (THE) Reputational Relationship. Scientometrics 2019, 121, 897–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli Palacio, A.; Díaz Meneses, G.; Pérez Pérez, P.J. The Configuration of the University Image and Its Relationship with the Satisfaction of Students. J. Educ. Adm. 2002, 40, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Castillo-Feito, C.; Blanco-González, A.; González-Vázquez, E. The Relationship between Image and Reputation in the Spanish Public University. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, R. Corporate Reputation: Meaning and Measurement. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.-G.; Yeo, C.-K.; Jang, M.-G. Corporate Social Responsibility in China: Consumers’ Attributions and Performance on CSR Activities. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 33, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Plewa, C.; Ho, J.; Conduit, J.; Karpen, I.O. Reputation in higher education: A fuzzy set analysis of resource configurations. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3087–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente-Ruiz-de-Sabando, A.; Forcada, J.; Zorrilla, P. The university image: A model of overall image and stakeholder perspectives. Cuad. Gest. 2018, 19, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L. Parents and the Role of University Social Responsibility in Shaping Student Identity and Attitudes. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Bringle, R.; Hatcher, J. Community-Based Partnerships for Social Responsibility: Engaging Faculty, Staff, and Students in Social Good Initiatives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1744. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Fostering Social Responsibility in Higher Education through Collaborative Partnerships. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6882. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- Vasilescu, R.; Barna, C.; Epure, M.; Baicu, C. Developing university social responsibility: A model for the challenges of the new civil society. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 4177–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Shafaei, A.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Daraei, M. Corporate social responsibility and universities: A study of top 10 world universities’ websites. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 440–447. [Google Scholar]

- Zomer, A.; Benneworth, P. The Rise of the University’s Third Mission. In Reform of Higher Education in Europe; Enders, J., de Boer, H.F., Westerheijden, D.F., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bat-Erdene, J.; Otgonbaatar, B. Social responsibility activities and reputation of universities. Mong. Educ. Res. 2021, 12, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Heding, T.; Knudtzen, C.F.; Bjerre, M. Brand Management: Research, Theory and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, D.J.; Gates, S.M.; Goldman, C.A. In Pursuit of Prestige: Strategy and Competition in U.S. Higher Education; Transaction Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, B.R. The Higher Education System: Academic Organization in Cross-National Perspective, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente-Ruiz-de Sabando, A.; Zorrilla, P.; Forcada, J. A review of higher education image and reputation literature: Knowledge gaps and a research agenda. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 24, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, D. Analyzing reputation of Swiss universities on Twitter—The role of stakeholders, content and sources. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2020, 25, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandon-Barbosa, D.; Salas-Paramo, J.; Moreno-Gómez, J. Academic reputation quality and research: An analysis of Latin-American universities in the world higher education institution rankings from the perspective of organizational learning theory. J. Further. High. Educ. 2023, 47, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, W.; Abratt, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and Reputation: The Importance of Reputation and Its Effect on the Relationship Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Financial Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, K.F. Measuring university social responsibility: A comparative study of universities in Pakistan. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 140, 511–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, Y.; Park, J. University social responsibility and student perception: The mediating effect of perceived social impact. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136534. [Google Scholar]

- Bichi, A.A. Evaluation of Teacher Performance in Schools: Implication for Sustainable Development Goals. Northwest. J. Educ. Stud. 2017, 2, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gyasi, R.S.; Xi, W.B.; Owusu-Ampomah, Y. Perspective analysis of the reputation of public basic school teachers in Ghana through students: The case of Accra in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Van Riel, C.B.M. Fame & Fortune: How Successful Companies Build Winning Reputations; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsley-Brown, J.; Oplatka, I. Universities in a competitive global marketplace: A systematic review of the literature on higher education marketing. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2006, 19, 316–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zheng, X. Evaluating the Impact of Graduate Contributions on University Rankings and Quality Assurance Systems. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, A.; Sulaiman, Z.; Qureshi, M.I. Student’s Perceived University Image Is an Antecedent of University Reputation. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, R. Planning and Implementing Institutional Image and Promoting Academic Programs in Higher Education. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2004, 13, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, A.K. Creative teaching and its assessment. In Quality Innovations for Teaching and Learning, Proceedings of the 12th UNESCO-APEID International Conference, Paper Presentation. Bangkok, Thailand, 24–26 March 2009; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bondar, T.; Varava, O. Distance Education and Education Quality at HEIs in Ukraine During COVID-19. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economics, Law and Education Research (ELER 2021), Kyiv, Ukraine, 10–11 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Benneworth, P.; Jongbloed, B. Who matters to universities? A stakeholder perspective on humanities, arts and social sciences valorisation. High. Educ. 2010, 59, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, Z. Evaluating Higher Education Institutions through Stakeholder Contributions: Faculty, Students, and Administrative Staff. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro, E.d.M.; Leitão, J.; Alves, H. HEI efficiency and quality of life: Seeding the pro-sustainability efficiency. Sustainability 2021, 13, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanevenhoven, J.; Liguori, E. The impact of entrepreneurship education: Introducing the Entrepreneurship Education Project. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, C.J.; Gangeness, J.E. Business, leadership, and education: A case for more business engagement in higher education. Am. J. Bus. Educ. 2019, 12, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyryanova, V.A.; Goncharova, N.A.; Orlova, T.S. Developing a Model of Strategic University Reputation Management in the Digitalization Period in Education. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference “Digitalization of Education: History, Trends and Prospects” (DETP 2020), Yekaterinburg, Russia, 23–24 April 2020; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 726–732. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro, E.d.M.; Alves, H.; Leitão, J. In search of intangible connections: Intellectual capital, performance, and quality of life in higher education institutions. High. Educ. 2022, 83, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, A.; O’Connell, D. The Role of Universities in Addressing Global Social Challenges: Social Responsibility and the Future of Education. High. Educ. Q. 2021, 75, 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Aledo-Ruiz, M.D.; Martínez-Caro, E.; Santos-Jaén, J.M. The influence of corporate social responsibility on students’ emotional appeal in HEIs: The mediating effect of reputation and corporate image. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, L.; Valverde, G. Higher Education and Community Engagement: A Framework for Social Responsibility. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 210. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hair, J.F.; Proksch, D.; Sarstedt, M.; Pinkwart, A.; Ringle, C.M. Addressing endogeneity in international marketing applications of partial least squares structural equation modeling. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C. The use of partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in management accounting research: Directions for future theory development. J. Account. Lit. 2016, 37, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Fosso Wamba, S.; Dewan, S. Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality. Prod. Plan. Control. 2017, 28, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, Z.; Qazi, W.; Raza, S.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. The antecedents affecting university reputation and student satisfaction: A study in higher education context. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2022, 25, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Velasquez Estrada, J.M.; Shatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Evaluating the predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dima, A.; Vasilache, S.; Ghinea, V.; Agoston, S. A model of academic social responsibility. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2013, 9, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tetrevova, L.; Sabolová, V. University stakeholder management and university social responsibility. WSEAS Trans. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2010, 7, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-H.; Na-Songkhla, J.; Donaldson, J.A. University social responsibility (USR): Identifying an ethical foundation within higher education institutions. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2015, 14, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi, L.; Sassen, R. How universities’ social responsibility activities influence students’ perceptions of reputation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 137963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnell, T. Community Engagement in Higher Education: Trends, Practices and Policies (NESET Report); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Godonoga, A.; Sarrico, C.S. Civic and social engagement of higher education. In Oxford Bibliographies in Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).