Abstract

The main purpose of this study is to explore the impact of internal and external corporate social responsibility perception (CSRP) on organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and the mediating effect of person–corporate social responsibility fit (P-CSR Fit) among staff members in Saudi Arabia’s banking industry. The existing literature offers limited exploration of mechanisms that enhance CSR effectiveness in influencing OCB. This study explores the mediating impact of P-CSR Fit on OCB, particularly within the developing country context of Saudi Arabia. A sample of 200 employees from banks in Saudi Arabia was surveyed to investigate these relationships, utilizing a structured questionnaire. Both SPSS and AMOS were utilized to assess the relationships and test the hypotheses within structural equation modeling. The study findings reveal that P-CSR Fit fully mediates the relationship between internal CSRP and OCB. However, external P-CSR Fit does not mediate the relationship between external CSRP and OCB. The discussion includes theoretical and practical implications, as well as study limitations.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is an organizational critical tool leveraged to attain sustainability. Edwards [1] argued that firms need to account for the social and environmental impacts of their business practices, along with organizational goals. Earlier research has explored the beneficial impacts of CSR on organizations and their diverse stakeholders. It has been associated with customer satisfaction [2], brand image [3], and employee engagement [4]. These benefits can lead to competitive advantages and improved performance [5].

Past studies [6,7] highlighted the need to understand how CSR leads to positive employee outcomes. In this context, positive CSR perception (CSRP) is linked to expectations of stakeholder value and employee motivation [8]. Aligned with the Saudi Vision 2030 for Sustainability, the Saudi economy and its constituent elements are expected to reflect and incorporate sustainability–CSR principles. To elaborate, the Saudi 2030 vision underscores important social responsibility initiatives targeting the environment, community, and individuals. More specifically, the socially responsible initiatives include sustainability, social infrastructure supporting families, education, and social care systems [9].

CSR can be an indicator of uniqueness and appeal for prospective employees. CSR activities involve voluntary efforts by organizations for the benefit of key stakeholders, especially when they perceive it to be valuable [8]. There are different classifications of CSR; most Asian studies use the internal/external classification system [10,11]. Internal CSR has a self-directed focus and is linked to the support and welfare of employees. It focuses on policies and practices that enhance the physical and psychological working environment for employees and organizational success [12]. Internal CSRP is related to providing financial and nonfinancial employee benefits, such as respect and appreciation. Research indicates that internal CSR positively influences employee attitudes and behaviors [13]. The external CSR is other-focused and underscores environmental and societal goals [13,14]. The external CSRP is linked to societal and cultural norms of community and environmental contribution, which enhance public image [15]. Enhancing the awareness of the external CSR can contribute to positive outcomes for stakeholders [16].

Based on the stakeholder theory, CSR initiatives can build a good reputation for a company and induce employee alignment with the organization [17]. Person–organization (P-O) fit can be defined as the alignment between organizational and employees’ values. Previous studies show that alignment between employees’ values and organizational values leads to more positive work attitudes [18]. Furthermore, P-O fit perception is shown to be linked to CSR initiatives [19]. A second-order construct called CSR P-O fit links employee CSR values to organizational CSR values. The organizational CSR efforts promote positive perception of job fit among employees, which leads to positive employee work outcomes. Furthermore, employees assess organizations based on values and traits reflected in their CSR policies and practices, and their personal alignment [18].

Culture can affect the CSRP of employees, and this has been called for future studies [20]. More specifically, stakeholders pressure organizations to adopt CSR initiatives. In Asian countries, there are high expectations placed on organizations due to the region’s collectivistic culture [21]. Ethical predisposition demands and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) for employees have been evaluated in past studies [13,22]. OCB is related to performing voluntary job tasks above and beyond what is required of employees. Therefore, the current study incorporates the CSR P-O fit, which includes Saudi culture-embedded predispositions in employees’ ethical decision-making [23].

This study adds to the existing body of knowledge by combining insights from generalized exchange theory, social identity theory, and congruence theory within the context of the banking industry. Its purpose is to explore how both internal and external CSR perceptions influence employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB), with a focus on the mediating effect of person–CSR fit. This approach broadens the scope of research on employee-centered corporate social responsibility.

The banking sector’s adoption of CSR and its implications are vital for many reasons. First, a fundamental expectation is that banks demonstrate social responsibility by compensating society for their use of resources in supporting lending activities that rely more on deposits than shareholder equity. Additionally, as “too big to fail” institutions, banks benefit from government bailouts [24]. Secondly, reputational risks and negative stakeholder opinions pose a significant challenge for financial institutions, which can be addressed through the implementation of strong CSR practices [25,26]. Lastly, bank lending is essential for driving sustainable development, as it enables investments and a transition in the real economy away from unethical activities [27]. In Saudi Arabia’s banking industry, the CSR fit between employees and organizations is often implicit.

Therefore, the primary goal of this research is to determine the impact of person–CSR fit on the link between CSRP and employee OCB. This lack of explicit CSR fit can lead to a misalignment in values, which can impact employees’ OCB [28]. Therefore, given the importance of CSR, organizations should prioritize understanding the role of personal values in shaping these key organizational elements.

This research addresses several important gaps. Firstly, person–CSR fit is a topic that has been called for further exploration [29]. Therefore, this research investigates the mediating role of CSR fit in predicting Saudi bank employees’ organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Workplace CSR fit is crucial for achieving beneficial outcomes in organizational performance. Secondly, there is a scarcity of research on this phenomenon, particularly within the developing country context of Saudi Arabia. By conducting research in Saudi Arabia, this study also contributes to filling this contextual gap. While studies exploring CSR fit remain limited, there has been little exploration of the Saudi Arabian context. Therefore, this paper attempts to address a prevailing gap in the literature by providing empirical evidence on the role of internal and external CSRP in predicting employee OCB through person–CSR fit in the banking sector of Saudi Arabia, a context of significant and growing interest. It addresses the gaps in terms of enhancing the effectiveness of CSR activities. More specifically, a mechanism of a refined employee individual predisposition route is the CSR P-O fit. It is linked to a general ethical organizational predisposition route, being CSRP with internal and external classification.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility

CSR is defined as the organizational actions and policies implemented with stakeholders’ considerations, taking into account economic, social, and environmental considerations [30]. It highlights the inherent responsibility that profit organizations have to society. While the primary goal of for-profit entities is financial gain, there can be conflicts between managerial and shareholder views on CSR. This discrepancy can create challenges when shareholders perceive CSR as a misallocation of resources, while managers view it as beneficial for organizational performance [31]. The increasing interest in CSR in recent years has spurred greater research and debate on the topic.

Carroll’s [32] CSR concept framework includes legal, economic, ethical, and discretionary aspects. The latter involves responsibilities beyond the economic, legal, and ethical realms. This model posits that organizations should pursue economic objectives while respecting legal constraints and adhering to societal ethical norms. Furthermore, they should voluntarily undertake discretionary activities addressing social expectations. While this definition, popularized by Carroll and Shabana [33], has been a cornerstone of CSR research for over three decades, measuring CSR remains a significant challenge. This challenge stems from the fact that legal, economic, and ethical expectations evolve over time, and discretionary expectations are even more fluid. Zink [34] emphasizes stakeholder expectations in sustainable CSR.

Micro-level studies have linked CSR to positive effects on employee outcomes, such as performance, commitment, OCB, engagement, and the quality of employee relationships [22,35,36,37]. While micro-level research on CSR has grown, our understanding of its direct impact on employees remains limited [38]. This limitation is due, in part, to the common use of aggregated CSR measures derived from external assessments that primarily capture highly visible activities such as charitable giving and philanthropy. These external assessments often fail to account for internal CSR initiatives that may be less visible but equally important to employees [39].

Capturing these internal CSR activities through the perceptions of internal stakeholders, namely employees, is critical for understanding employee attitudes, behaviors, and job performance. The domain of CSR is complex and presents challenges in defining its scope and distinguishing it from business ethics [40]. However, examining employee perceptions provides a valuable lens for understanding its impact on those within the organization. A systematic review on CSR and employee outcomes has shown that CSR is complex to measure [29]. It can be measured according to perception with different dimensions, being stakeholder based [41], internal and external [14], intrinsic and extrinsic attribution [42], embedded and peripheral [30], substantive and symbolic [43], strategy fit [44], and authenticity [45]. Employees further classify internal and external CSRP based on whether it benefits the self or others [8].

This study will utilize the internal/external CSR dimension because of its direct relevance to organizational attitudes and behavior. This differentiation is critical for understanding how employees perceive CSR. The perceived external CSR (focused on society, the environment, and customers) encompasses the organization’s activities that benefit external stakeholders, while perceived internal CSR (focused on employees) pertains to self-oriented activities designed to benefit internal stakeholders. Most Asian studies use the internal and external classifications of CSRP in determining employees’ decision-making. For example, CSRP has been linked to employee emotional labour strategy choice [10,11]. Furthermore, OCB employee behavior is especially important for frontline bank employees who face customers. Therefore, it is vital to understand the ethical predisposition mechanisms for inducing this behavior.

Employees’ impact is vital, since they benefit from internal CSR efforts and also play a role in the external initiatives. Thus, how employees perceive the two kinds of CSR is likely to develop through personal processes and have varied effects on behaviors. Furthermore, there are calls for studies to investigate mechanisms by which CSR affects employee outcomes [46,47].

2.2. Theoretical Foundation

CSRP can be understood as an individual’s ethical decision-making and their predisposition. Ethical predisposition is defined as the cognitive framework for moral decision-making [48]. It can be divided into two paths, namely utilitarianism and formalism. The utilitarianism path underscores the consequences of actions as being ethical, while formalism focuses on the ethicality of actions themselves. CSRP can fall into the formalism framework, where it subscribes to a set of actions and principles to guide behavior [48]. Employees with strong formalist CSRP would value firms with strong CSR reporting and initiatives. On the other hand, employees with a strong utilitarian view have a negative CSRP. They stress high economic performance and care about the consequences of ethical actions, similar to remuneration as motivation for employees [49]. Furthermore, culture plays a vital role in ethical predisposition, where it can influence it significantly. More specifically, in Saudi Arabia, cultural community service in terms of financial support, etc., is highly regarded as virtuous and good. Therefore, Saudi employees would view firms with high external CSR investments as having positive CSRP. This would promote public image, as well as support from internal stakeholders and employees [50].

The concept of reciprocity between the employee and the organization is initiated with firms’ investment in positive values and societal concerns. It leads to employees reciprocating with increased loyalty, engagement, or productivity [51]. More specifically, the concept of giving back to the community is highly virtuous in Saudi culture and among employees [50]. Eventually, it positively affects the firm by inducing employee OCB. Therefore, being strongly oriented toward ethical formality CSRP, and employees valuing external CSRP, can be linked to a strong CSR P-O fit. The CSR P-O fit is an individualized CSR ethical predisposition that is shared and aligns with the organization’s CSR values.

According to the congruence theory [52], individuals maintain consistent internal beliefs when faced with new information through mechanisms. Holland [53] expanded this theory to analyze the impact of individuals’ interactions with their environment. The theory posits that people can have varying attitudes toward their surroundings based on their evaluations. Although these attitudes are distinct, they can connect when an event links them, leading one attitude to inform the other. For example, when two parties share a positive perspective on an event, they experience agreement and joy. Conversely, conflicting views can create discomfort or conflict, as the new information challenges existing attitudes. Therefore, it is posited that when both CSRP and CSR P-O fit for an employee and an organization are aligned and congruent, it leads to positive work outcomes and OCB.

Social Exchange Theory suggests that the relationship between CSR and OCB is influenced by reciprocity. Employees who perceive they are valued by their organization are more likely to participate in voluntary behaviors [54]. Employees proactively interpret organizational practices, which shapes their attitudes and behaviors. The perception of fairness within the organization is also a critical factor [55].

The psychological needs-satisfaction paradigm suggests that employees’ needs for social connection, belonging, security, and status influence their responses to organizational practices. Many researchers suggest a positive link between employees’ heightened CSR awareness and beneficial work-related outcomes [8,41,56]. This results in emotional engagement and community connection, which enhance employee OCB [54].

The generalized exchange theory may explain how internal/external CSRP initiatives influence employee OCB. Work engagement serves as an intermediary between CSRP and employee OCB. Generalized exchange involves the transfer of resources, social capital, or assistance among groups and communities, serving as a key driver for prosocial behavior, OCB, and positive organizational outcomes [57]. These constructs, in turn, are linked to improved member performance, coworker identification, and OCB [58].

Two primary mechanisms govern exchange systems within organizations: generalized reciprocity and indirect reciprocity. In generalized reciprocity, individuals who have been the beneficiaries of assistance are motivated to extend help to others by gratitude, thereby creating a cycle of reciprocal support. In contrast, indirect reciprocity involves individuals gaining a positive reputation through their helpful actions, leading to subsequent assistance from third parties [57,59]. These theoretical distinctions are supported by empirical research examining prosocial behavior in organizational settings. This paper employs a similar approach to Hu et al. [60] by implementing socially responsible practices that are focused internally and externally within an organizational context. Therefore, external CSR practices benefit stakeholders such as the community, consumers, suppliers, and shareholders, whereas internal CSR initiatives primarily benefit employees [61].

Drawing on generalized exchange theory, this research posits that employees are inclined to reciprocate the advantages they receive from internal CSR initiatives within the bank, including employee education programs, work training, and the provision of safe working environments [7]. This fosters a sense of symbiosis between employees and employers, positively influencing trust and perceived organizational support [62]. Furthermore, indirect reciprocity is triggered when employees perceive their bank as committed to some practices concerning social responsibilities within the local community and the natural environment. External CSR initiatives enhance an organization’s reputation among employees, leading to increased esteem, trust, and influence [63]. This positive perception encourages employees to engage in beneficial actions and promotes OCB.

2.3. Internal Corporate Social Responsibility Perception (CSRP) and Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)

Internal CSRP addresses its responsibility toward internal stakeholders, primarily its employees [64]. Internal CSRPs are not confined to cultural expectations or meeting basic legal standards [8] and ethical formalism. While external CSR benefits stakeholders outside the organization, internal CSR specifically addresses the interests of current employees [65].

It revolves around organizational practices that promote employees’ well-being, such as safeguarding employee rights, healthcare benefits, career advancement opportunities, and equal treatment [15]. Past research has examined the influence of the proximity of CSRP on employees. Understanding the difference in proximity in CSRP is critical, as it can convey distinct internal organizational messages about values. Internal CSR reflects a commitment to the well-being and development of employees. These differing emphases can lead to varied employee attitudes and responses [15]. Internal CSRP develops perceived respect, indicating employees’ perception of how they are valued within the organization [66]. Both perceived prestige and respect, in turn, positively influence employee attitudes and organizational identification [66]. Supporting these findings, Farooq et al. [8] showed that different forms of organizational citizenship behavior are affected by differing forms of CSRP. Internal CSRP fosters a sense of respect among employees, as it signals that the organization values and supports its internal members. Based on the above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Internal CSRP is positively connected to employee OCB.

2.4. External Corporate Social Responsibility Perception (CSRP) and Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)

External CSRP encompasses an organization’s responsibility toward external stakeholders, including society, the environment, and customers [64]. It emphasizes environmental and social practices that enhance the organization’s image among societal audiences [67]. A focus on external CSR signals the organization’s commitment to the community, customers, and the environment, which can affect employee outcomes differently [15]. Analysis indicates that employees’ perceptions of external CSR positively influence their sense of organizational prestige, highlighting how they view their company’s reputation from the perspective of external stakeholders [66]. External CSRP can impact organizational citizenship behavior through mechanisms. Specifically, it enhances employees’ sense of organizational prestige, as it reflects the company’s positive image in the eyes of external stakeholders [8].

OCB can affect internal stakeholders, as well as external ones. It can enhance service delivery, customer satisfaction, or public image. Behaviors such as courteous service behaviors or advocacy for organizational values in public settings can be seen as externally oriented. Bavik et al. [68] extended this idea by proposing that OCB can target external groups like customers or the general public, especially in service-intensive industries where employee conduct significantly shapes stakeholder perceptions.

This broader understanding highlights that OCB may not only contribute to internal harmony and performance but also play a role in strengthening external stakeholder relationships and enhancing the organization’s reputation in the wider social context. Based on the above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

External CSRP is positively connected to employee OCB.

2.5. The Mediating Role of Person–CSR Fit

Under supplementary fit, an individual’s characteristics align with those of their environment, resulting in the individual fitting in with the existing conditions. The fit can also refer to the alignment of personality, values, attitudes, needs, preferences, goals, skills, and knowledge [69]. Person–organization (P-O) fit is conceptualized as the perceived congruence between an organization and an individual. This alignment stems from the reciprocal fulfillment of needs, the sharing of similar core values, or a combination thereof. Research in P-O fit links it to positive outcomes such as enhanced organizational commitment, job satisfaction, citizenship behavior, and improved performance. Simultaneously, a strong P-O fit mitigates adverse consequences, including employee deviance [70]. Therefore, the alignment between an individual’s CSR values and an organization’s CSR activities can be linked to person-environment compatibility. This conceptualization has implications for individual and organizational outcomes.

Similarly, Im et al. [69] expanded this framework to encompass a second-order construct: person–CSR fit. Rooted in the established psychological and organizational construct of “fit” [71], this conceptualization extends P-O fit to specifically address CSR alignment. Person–CSR fit denotes the congruence between an individual’s personal CSR values and an organization’s CSR values. The study proposes a mechanism of a refined employee individual predisposition route being the person–CSR fit.

Positive CSRP is linked to a positive perception of the organization [65]. As perceived stakeholder obligations are related to CSR activities, these actions affect external and internal stakeholders.

Glavas and Godwin [69] contended that individuals are more likely to seek employment with organizations demonstrating values alignment and providing opportunities consistent with their personal values. Greguras et al. [72] suggested that engaging employees in CSR initiatives can enhance alignment between their personal values and organizational values. Furthermore, Farooq et al. [46] found that employees’ perceptions of CSR influence their fit with the organization, emphasizing the role of perceived CSR alignment. Implementing supplementary fit in organizations is expected to improve work attitudes and motivation in employees [73]. Empirical evidence suggests that P-O fit mediates the relationships with job satisfaction, turnover, turnover intentions, job commitment, and performance [74]. Consistent with this, Oh et al. [20] and Kristof-Brown et al. [75] found that P-O fit, alongside other variables, predicts job attitudes, such as organizational commitment. This research suggests that employees’ perceptions of CSR (both internal and external) impact their sense of fit and identification with the organization [76]. Lee et al. [77] found that employees have a stronger connection to their organization when CSR practices are driven by intrinsic values rather than utilitarian goals. Therefore, the paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H3.

Person-CSR fit mediates the relationship between internal (H3a) and external (H3b) CSR perception and organizational citizenship behavior.

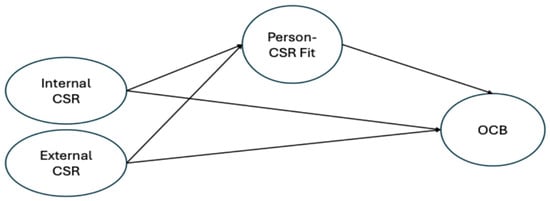

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed conceptual model, highlighting the key components and their interrelationships. As shown, the model emphasizes the interaction between internal and external CSR perception and organizational citizenship behavior and the mediating role of Person-CSR fit, this illustration helps to clarify the theoretical foundation of our study and guides the subsequent analysis.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the proposed conceptual model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach and Sample

This study employed a nonprobability convenience sampling method utilizing a self-administered online survey distributed in Saudi Arabia. The target population consisted of bank employees at various hierarchical levels within the institution. Participants were contacted via social media platforms and other communication channels with a request to complete and disseminate the survey within their respective working groups. The number of completed surveys was 200, from the period of 1 May to 15 May 2024. The banks in Saudi Arabia include 11 domestic and 23 foreign banks. The original scales were translated into Arabic using forward and backward translation [78]. The translation process began with a forward translation, conducted by a bilingual Saudi translator who converted the items into Arabic. The translator was provided with detailed information about the constructs being measured to ensure the original meaning was preserved. Subsequently, the research team reviewed the translated version to verify its consistency with the original instrument. Before proceeding to data collection, two bilingual experts in the business field assessed the face validity of the questionnaire. Only minor adjustments were suggested and subsequently implemented to refine the Arabic version.

3.2. Measures

This study employed a survey instrument comprising statements designed to evaluate employees’ perception of their bank’s CSR activities, P-O fit, and OCB. All items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale. Employees’ CSRPs, encompassing both internal and external dimensions, were measured using a ten-item scale adapted from Perez and Del Bosque’s [79] CSR assessment tool. This scale evaluates internal aspects, such as CSR toward employees, using four items. Additionally, it assesses external dimensions, including CSR toward customers, stakeholders, and society, using six items. P-O Fit was measured using a three-item scale adapted from Cable and DeRue [80].

3.3. Characteristics of the Study Sample

Table 1 summarizes the demographic attributes of the 200 respondents. The sample comprised 60.5% females and 39.5% males. Most respondents were under 30 years of age (68%) and held a bachelor’s degree (92.5%). The majority also had 1–5 years of experience within their organization (64.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants (n = 200).

3.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were analyzed using SPSS 29. To evaluate the measurement model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted with AMOS to estimate the model parameters. Subsequently, the research hypotheses were examined through structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 27.

3.4.1. Descriptive Analytics

Table 2 presents the descriptive analytics for the proposed model.

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation (SD), and correlation statistics.

3.4.2. Measurement Model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the validity of the hypothesized model, examining the relationships between the factors and their observed indicators. The CFA results indicated an acceptable model fit to the data [81], as shown in Table 3. Furthermore, the factor loadings were found to be acceptable, confirming that the observed variables are strongly associated with their respective latent constructs, as detailed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Model fit of confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 4.

CFA results.

Additionally, the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values were above the recommended thresholds of 0.70 and 0.50, respectively [82]. According to the guidelines outlined by Hair et al. [80], the composite reliability (CR) value should exceed the average variance extracted (AVE) value to ensure adequate construct reliability. In this analysis, this condition was satisfied, thereby confirming the constructs’ convergent validity.

3.4.3. Common Method Bias

When data are gathered at a single time point, the likelihood of encountering common method bias tends to increase. To evaluate this, three models—the unconstrained model, the equal loadings model, and the zero-to-equal loadings model—were constructed, each including a shared latent factor (CLF). The results indicated that the unconstrained model fit the data better than the nested alternatives, based on the p-value significance levels. This suggests that common method bias is present in the data. Of the three models, the unconstrained one provided the most optimal fit, justifying the decision to keep the CLF within the structural model. As a result, factor scores were used to generate the composite measures, helping to mitigate the bias.

3.4.4. Hypothesis Testing

Table 5 displays the findings related to the direct, indirect, and total impacts within the tested structural model. The results indicate that perceived external CSR has a positive and significant effect on OCB (β = 0.507, p < 0.00). Hence, H2 is supported. However, the results revealed that there is a negative and significant relationship between perceived internal CSR and OCB (β = −0.397, p < 0.00). Hence, H1 is rejected. The mediating effect of person–CSR fit on the relationship between perceived internal CSR and OCB was found to be significantly positive (β = 0.348, p < 0.001), indicating a full mediating role. Consequently, hypothesis H3a was supported. In contrast, the mediating effect of person–CSR fit on the relationship between perceived external CSR and OCB was not statistically significant (β = −0.005, p > 0.05), suggesting no mediating influence. Therefore, hypothesis H3b was rejected. The results of the structural model test are illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 5.

Structural model results.

Figure 2.

Hypothesized model and standardized estimate. Note: *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

This study primarily aims to explore how employees’ perceptions of both internal and external corporate social responsibility (CSR) influence organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), with a focus on the mediating role of person–CSR fit within the banking industry in Saudi Arabia. The results indicate that perceptions of external CSR have a direct and significant impact on OCB. However, the mediating effect of person–CSR fit in this relationship was not statistically significant. In contrast, the direct relationship between internal CSR perceptions and OCB was negative and unsupported, while the mediating role of person–CSR fit between internal CSR perceptions and OCB was positive and statistically significant.

These results contradict previous research that has suggested internal CSR perceptions lead to greater benefits for OCB than external CSR perceptions [83]. However, our findings align with those of Chou et al. [84], which indicate that internal perceptions significantly influence employee citizenship behaviors through the mediation of employee-company identification and value congruence. This underscores the necessity of cultivating a supportive internal CSR environment, which not only enhances employee engagement but also fosters a stronger alignment between employees’ values and those of the organization. The findings regarding the mediating role of person–CSR fit in the relationship between external CSR perceptions and OCB warrant further discussion. The lack of a significant mediation effect in this context may be influenced by cultural, contextual, or organizational factors specific to the Saudi banking sector. For instance, external CSR initiatives are often viewed by employees as primarily related to the organization’s reputation and societal image, which may not directly influence their sense of personal alignment or fit with the organization. Additionally, cultural norms and societal expectations within Saudi Arabia could shape employees’ perceptions of external CSR differently, potentially diminishing its impact on individual-level psychological constructs such as person–CSR fit.

Furthermore, aligning with our findings, a thorough meta-analysis of 140 studies indicates that CSR has a stronger link to employees’ psychological and emotional reactions—such as trust in and pride toward the organization—as well as their work attitudes like commitment. Conversely, the influence of CSR on work-related behaviors, particularly organizational citizenship behavior, seems to be comparatively weaker [50]. Our results offer empirical support that perceptions of internal CSR can affect organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) via the mediating influence of person–CSR fit. Consequently, this research advances the current body of knowledge by being among the first to empirically demonstrate the mediating role of person–CSR fit in the link between internal CSR perceptions and OCB.

5. Implications

This research offers several important theoretical contributions to the field. While prior studies have predominantly emphasized the influence of external CSR perceptions on fostering employees’ positive attitudes and behaviors, this study shifts the focus toward understanding the role of internal CSR perceptions [60,65]. This study enhances the current body of knowledge by offering a more comprehensive understanding of how person–CSR fit influences the link between internal CSR perceptions and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) in the banking industry of Saudi Arabia.

Moreover, the findings of this study hold significant implications for practitioners. Our findings suggest that a sole focus on external CSR practices is not sufficient; it is crucial to consider the personal relevance of CSR activities to employees. Managers can enhance employee engagement in CSR programs and increase awareness of relevant social issues. Therefore, Saudi bank managers should adapt to cultural norms and enhance them to resonate with employees’ individualistic ethical perceptions, in order to enhance organizational outcomes. The cultural side leans toward community and social giving, which emphasizes the external CSRP. Also, human resources have a vital job, which is selecting employees with CSR values that are in congruence with the organization, to enhance CSR effectiveness.

Furthermore, it is essential for managers to recognize the potential heterogeneity in employee preferences regarding CSR fit, especially in predominantly Islamic countries where external CSR initiatives, such as mandatory zakat contributions, carry significant cultural and religious importance. This paper advocates for careful consideration of these factors to ensure that CSR initiatives align with employee values and yield tangible benefits for the community.

Our research provides valuable insights for practitioners and contributes to the ongoing discourse on CSR in the banking sector.

6. Limitations

This study is constrained by specific limitations that necessitate consideration in subsequent inquiries. By increasing the survey sample size and incorporating qualitative data from interviews, more accurate estimates and a thorough analysis can be achieved. One limitation identified is the gender and age distribution within the sample, where more females participated in the survey than males. In addition, subsequent studies could explore the interplay between CSR fit, CSR perception, and organizational behavior across a broader spectrum of industries, extending beyond the banking sector. While the present study focused on employee CSR fit and perception within the banking context, future research could examine other sectors, such as service or manufacturing, to augment the general applicability of the results. Moreover, future studies could investigate different forms of CSR fit as well as explore additional mediating variables, like work-related attitudes, including work engagement or work commitment. Finally, the study’s cross-sectional design may introduce concerns regarding common method bias. To mitigate this limitation and enhance causal inference, conducting a longitudinal study would provide a more comprehensive perspective on the potential relationships between the underlying variables.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.D.; software, K.A.; validation, S.D.; formal analysis, K.A.; investigation, K.A.; data curation, K.A.; writing—original draft, K.A.; writing—review and editing, S.D.; supervision, S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the research supporting program (ORF-2025-1023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of King Saud University (No. KSU-HE-22-213; date: 22 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to participants’ privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Edwards, R.A. The Sustainability Revolution: Portrait of a Paradigm Shift; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, P.M. Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, H. The business case for CSR: Where are we? Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2003, 5, 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gürlek, M.; Tuna, M. Corporate social responsibility and work engagement: Evidence from the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Lee, J.H.; Byun, R. Does ESG performance enhance firm value? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, E.D.; Mallory, B.D. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.-P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, E.D.; Farooq, M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Qattan, A. Vision 2030 and Sustainable Development: State Capacity to Revitalize the Healthcare System in Saudi Arabia. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2021, 58, 46958020984682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, N.; Todres, M.; Janjuha-Jivraj, S.; Woods, A.; Wallace, J. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Social Enterprise. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.S.; Du, J.; Anwar, F.; Khan, H.S.U.D.; Shahzad, F.; Qalati, S.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Reciprocity Between Employee Perception, Perceived External Prestige, and Employees’ Emotional Labor. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility: A Scale Development Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Riaz, Z.; Arain, G.A.; Farooq, O. How Do Internal and External CSR Affect Employees’ Organizational Identification? A Perspective from the Group Engagement Model. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.-W.; Choi, W.-H. When are internal and external corporate social responsibility initiatives amplified? Employee engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives on prosocial and proactive behaviors. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing Business Returns to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of CSR Communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, S.T.; Yee, K.V.; Khor, K.S. Developing a Measurement Instrument for Perceived Corporate Citizenship Using Multi-Stakeholder, Multi-Industry and Cross-Country Validations. Qual. Quant. 2022, 57, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.A.; Mouro, C. Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility and Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Person-Organization Fit and Organizational Identification’s Sequential Mediation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, P.; Jiang, C. How and When Does Socially Responsible HRM Affect Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors Toward the Environment? J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-H.; Hwang, Y.; Kim, H. Is Deep Acting Prevalent in Socially Responsible Companies? The Effects of CSR Perception on Emotional Labor Strategies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, S.; Sadaf, R.; Popp, J.; Vveinhardt, J.; Máté, D. An Examination of Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Behavior: The Case of Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, Y.E.; Jung, H.; Park, I.-J. Psychological factors linking perceived CSR to OCB: The role of organizational pride, collectivism, and person–organization fit. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.A.; Lamya, A.-A.; Krishnan, K.S. Work Involvement and Ethics in Saudi Arabia. J. Transnatl. Manag. 2023, 28, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-W.; Shen, C.-H. Corporate social responsibility in the banking industry: Motives and financial performance. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 3529–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornett, M.M.; Erhemjamts, O.; Tehranian, H. Greed or good deeds: An examination of the relation between corporate social responsibility and the financial performance of US commercial banks around the financial crisis. J. Bank. Financ. 2016, 70, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Whysall, P. Performance, reputation, and social responsibility in the UK’s financial services: A post-‘credit crunch’interpretation. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 1991–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Sustainability benchmarking of European banks and financial service organizations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2005, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L. A qualitative analysis of corporate social responsibility in Saudi Arabia’s service sector-practices and company performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, Y.; Beckmann, M. CSR and employee outcomes: A systematic literature review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 75, 595–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. Embedded versus peripheral corporate social responsibility: Psychological foundations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 6, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziner, A. Corporative social responsibility (CSR) activities in the workplace: A comment on Aguinis and Glavas (2013). Rev. De Psicol. Del Trab. Y De Las Organ. 2013, 29, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Shabana, M.K. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, J.K. Stakeholder orientation and corporate social responsibility as a precondition for sustainability. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2005, 16, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassar, A.-N.; Yunis, M.M.; Alsagheer, A.; Tarhini, A.A.; Ishizaka, A. Effect of Corporate Ethics and Social Responsibility on OCB: The Role of Employee Identification and Perceived CSR Significance. In Management in the MENA Region; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- Luu, T.T. CSR and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in hotel industry: The moderating roles of corporate entrepreneurship and employee attachment style. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2867–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Ahmad, S.; Islam, T.; Kaleem, A. The nexus of corporate social responsibility (CSR), affective commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour in academia: A model of trust. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 42, 232–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.P. A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: Its evolutionary path and the road ahead. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Gusmerottia, N.M.; Corsini, F.; Passetti, E.; Iraldo, F. Factors affecting environmental management by small and micro firms: The importance of entrepreneurs’ attitudes and environmental investment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C. Managing a company crisis through strategic corporate social responsibility: A practice-based analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunda, M.M.; Ataman, G.; Behram, N.K. Corporate social responsibility and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of job satisfaction. J. Glob. Responsib. 2019, 10, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Akhouri, A. CSR Attributions, Work Engagement and Creativity: Examining the Role of Authentic Leadership. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Donia, M.B.L.; Ronen, S.; Sirsly, C.-A.T.; Bonaccio, S. CSR by any other name? The differential impact of substantive and symbolic CSR attributions on employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, P.; Aqueveque, C.; Duran, J.I. Do employees value strategic CSR? A tale of affective organizational commitment and its underlying mechanisms. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-M.; Yoon, S.-J. The effect of customer citizenship in corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on purchase intention: The important role of the CSR image. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Commitment: Exploring Multiple Mediation Mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, O.; Islam, J.U. Influence of CSR-Specific Activities on Work Engagement and Employees’ Innovative Work Behaviour: An Empirical Investigation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 3054–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, N.F. A Janus-Headed Model of Ethical Theory: Looking Two Ways at Business/Society Issues. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.H. A Formal Theory of the Employment Relationship. Econometrica 1951, 19, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.A.; Abdulrahman, A.-A. Corporate Social Responsibility in Saudi Arabia. Middle East Policy 2012, 19, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Nielsen, I.; Miao, Q. The Impact of Employee Perceptions of Organizational Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Job Performance and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Evidence from the Chinese Private Sector. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 1226–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, E.C.; Tannenbaum, P.H. The Principle of Congruity in the Prediction of Attitude Change. Psychol. Rev. 1955, 62, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, L.J. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Careers; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, S.M. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; Singh, R.K. Employee-level consequences of perceived internal and external CSR: Decoding the moderation and mediation paths. Soc. Responsib. J. 2023, 19, 38–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Sahay, A.; Arora, A.P.; Chaturvedi, A. A toolkit for designing firm level strategic corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Soc. Responsib. J. 2008, 4, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.N.Y.; Aprim, E.K. Do corporate social responsibility practices of firms attract prospective employees? Perception of university students from a developing country. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2018, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.-L.; Zhong, C.-B.; Organ, W.D. Organizational citizenship behavior in the People’s Republic of China. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.W.; Bulkley, N. Paying it forward vs. rewarding reputation: Mechanisms of generalized reciprocity. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 1493–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. The impact of employees’ perceived CSR on customer orientation: An integrated perspective of generalized exchange and social identity theory. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2345–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, D.J.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it pay to be good... and does it matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial per-formance. SSRN Electron. J. 2009, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, R. Groups reward individual sacrifice: The status solution to the collective action problem. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 74, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, A.D.; Tushman, M.L. A congruence model for organizational assessment. In Organizational Assessment: Perspectives on the Measurement of Organizational Behavior and the Quality of Work Life; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 261, p. 278. [Google Scholar]

- El Akremi, A.; Gond, J.-P.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K.; Igalens, J. How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 619–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y. The consequences of employees’ perceived corporate social responsibility: A meta-analysis. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavik, A.; Bavik, L.Y.; Tang, M.P. Servant leadership, employee job crafting, and citizenship behaviors: A cross-level investigation. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L.N. Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozes, M.; Josman, Z.; Yaniv, E. Corporate social responsibility organizational identification and motivation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, N.; Sliter, M.; Frost, C.T. What employees dislike about their jobs: Relationship between personality-based fit and work satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 71, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, W., Jr.; Bell, S.T.; Villado, A.J.; Doverspike, D. The use of person-organization fit in employment decision making: An assessment of its criterion-related validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Hartog, D.N.D.; Boselie, P.; Paauwe, J. The relationship between perceptions of HR practices and employee outcomes: Examining the role of person–organisation and person–job fit. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 138–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I.-S.; Guay, R.P.; Kim, K.; Harold, C.M.; Lee, J.-H.; Heo, C.-G.; Shin, K.-H. Fit happens globally: A meta-analytic comparison of the relationships of person–environment fit dimensions with work attitudes and performance across East Asia, Europe, and North America. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 99–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, W.R. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Piderit, S.K. How does doing good matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on employees. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2009, 36, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, A.; del Bosque, I.R. Measuring CSR image: Three studies to develop and to validate a reliable measurement tool. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, M.D.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekas, K.H.; Bauer, T.N.; Welle, B.; Kurkoski, J.; Sullivan, S. Organizational citizenship behavior, version 2.0: A review and qualitative investigation of OCBs for knowledge workers at Google and beyond. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Hansen, E.; Cai, J. Synthesizing and Comparing the Different Effects Between Internal and External Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Need Theory Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, E.-Y.; Liang, H.-Y.; Lin, J.-S.C. Believe to Go the Extra Mile: The Influence of Internal CSR Initiatives on Service Employee Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2021, 31, 845–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; Singh, R.K. Synthesizing the Affinity Between Employees’ Internal-External CSR Perceptions and Work Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 1053–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, J.S.; Nwachukwu, S.L.; Barnes, J.H. The Effects of Culture on Ethical Decision-Making: An Application of Hofstede’s Typology. J. Bus. Ethics 1993, 12, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).