1. Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is made up of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—a roadmap for global development efforts to 2030 [

1]. Some argue that the SDGs, while ambitious, are too broad and are “senseless, dreamy, and garbled”, making prioritization and measurement of progress difficult [

2]. So how can we balance global and local sustainability goals and actions?

Our world’s coral reefs have reached a crisis point and in the last three decades alone, we have lost more than half of the world’s corals, including large swaths of the iconic Great Barrier Reef [

3]. Protecting the Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral reef, is not a feat that can be achieved single-handedly or by the government alone. Paradoxically, Australia is a world leader in marine protected areas [

4] and one of the worst in the world, assessed as ‘insufficient’ and ‘critically insufficient’ [

5] and ranked 52 out of 67 countries for climate action [

6]. Sometimes it takes an innovative idea or a leader to inspire the community to take action. Without taking action, coral reefs as we know them today—and their associated services, food production, shoreline protection, tourism, economic resources, and cultural values—could be one of the first major ecosystems in this century to collapse under the weight of climate change and subsequent anthropogenic impacts [

7].

The intersection of art and sustainability can be a source of controversy, with debates arising around issues like greenwashing, the ethical sourcing of materials, and the impact of art on the environment [

8]. Our opinion in this article is that environmental art is an innovation that has costs and benefits, and the positives include raising awareness about environmental issues, promoting sustainable lifestyle practices, fostering a connection with nature, and encouraging creative expression and engagement of communities with ongoing ecological problems. Underwater museums originated in 2006 and generally take the form of a series of immersive sculptures that are installed directly onto the seabed. Presently there are eight underwater museums worldwide, which include the Museum of Underwater Art (MOUA) located on the central region of the Great Barrier Reef. These new forms of underwater museums promote an aesthetic experience in an oceanic context while raising awareness of marine biodiversity and the importance behind its preservation [

9,

10]. These underwater museums are strongly connected to the theoretical framework of sustainable tourism which has been defined as an approach considering the environmental, social, and economic influence and impacts on the present and future [

11]. The underwater museums also introduce a critical dimension of cultural policy and preservation, bringing a unique opportunity to explore, preserve, and educate visitors about the local cultural heritage [

11].

MOUA Ltd. (Townsville, QLD, Australia), the Not-for-Profit company and charity was established in 2017. MOUA’s vision is to provide a submerged experience that inspires reef conservation and engages the local community in the cultural land and sea stories regarding how to better conserve, protect, and restore the reef for future generations [

12].

Museums generally rely on a mix of funding sources, including government grants, private donations, corporate supporters, and earned income. Museums operate with significant costs, including buildings, exhibits, staff, insurance, and technical equipment. To build income, the reliance on hosting exhibitions and events is a method that aims to increase local visitor activities and involvement.

The Artist and the Sculptures

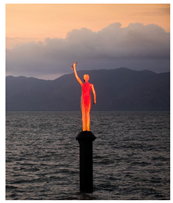

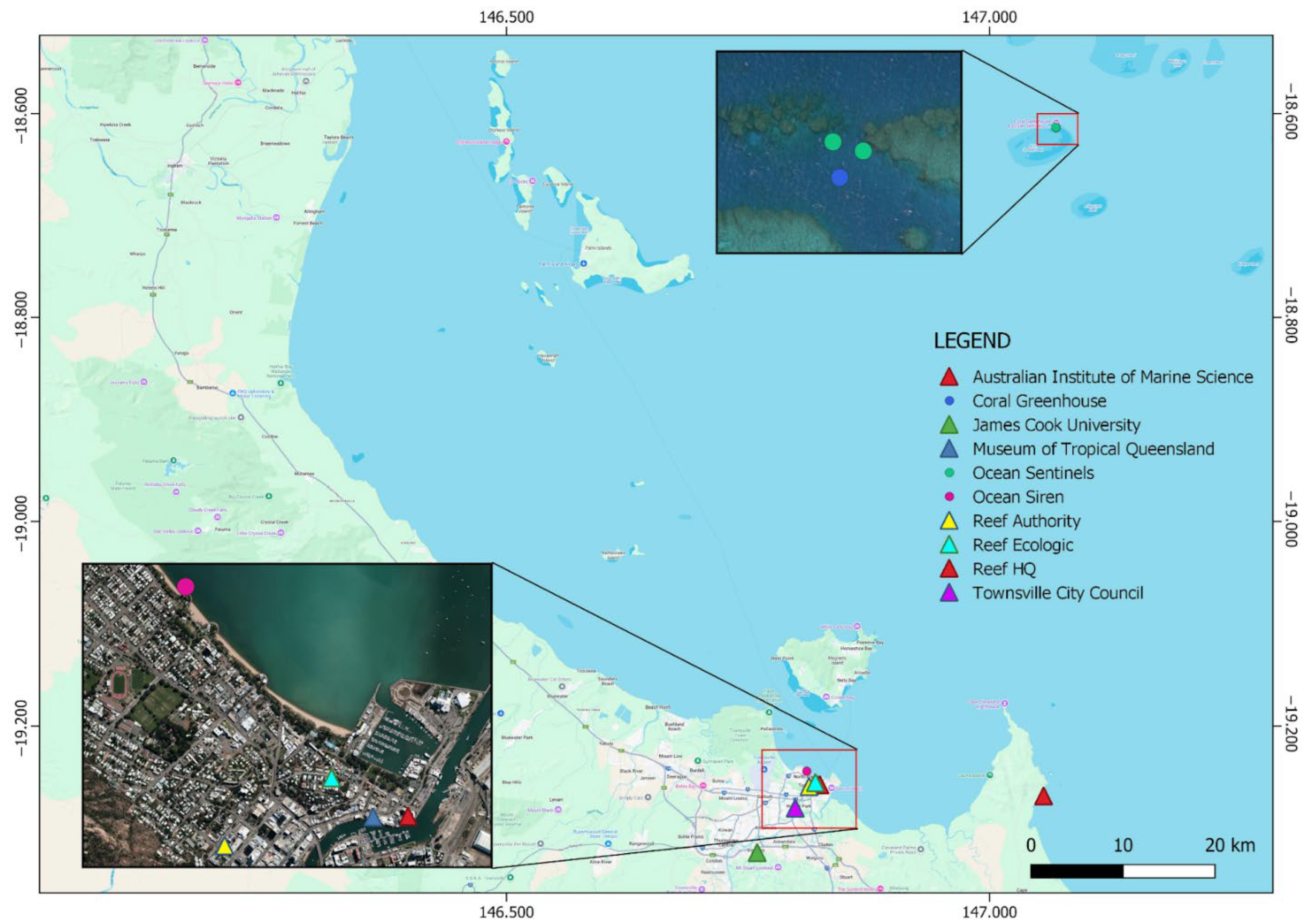

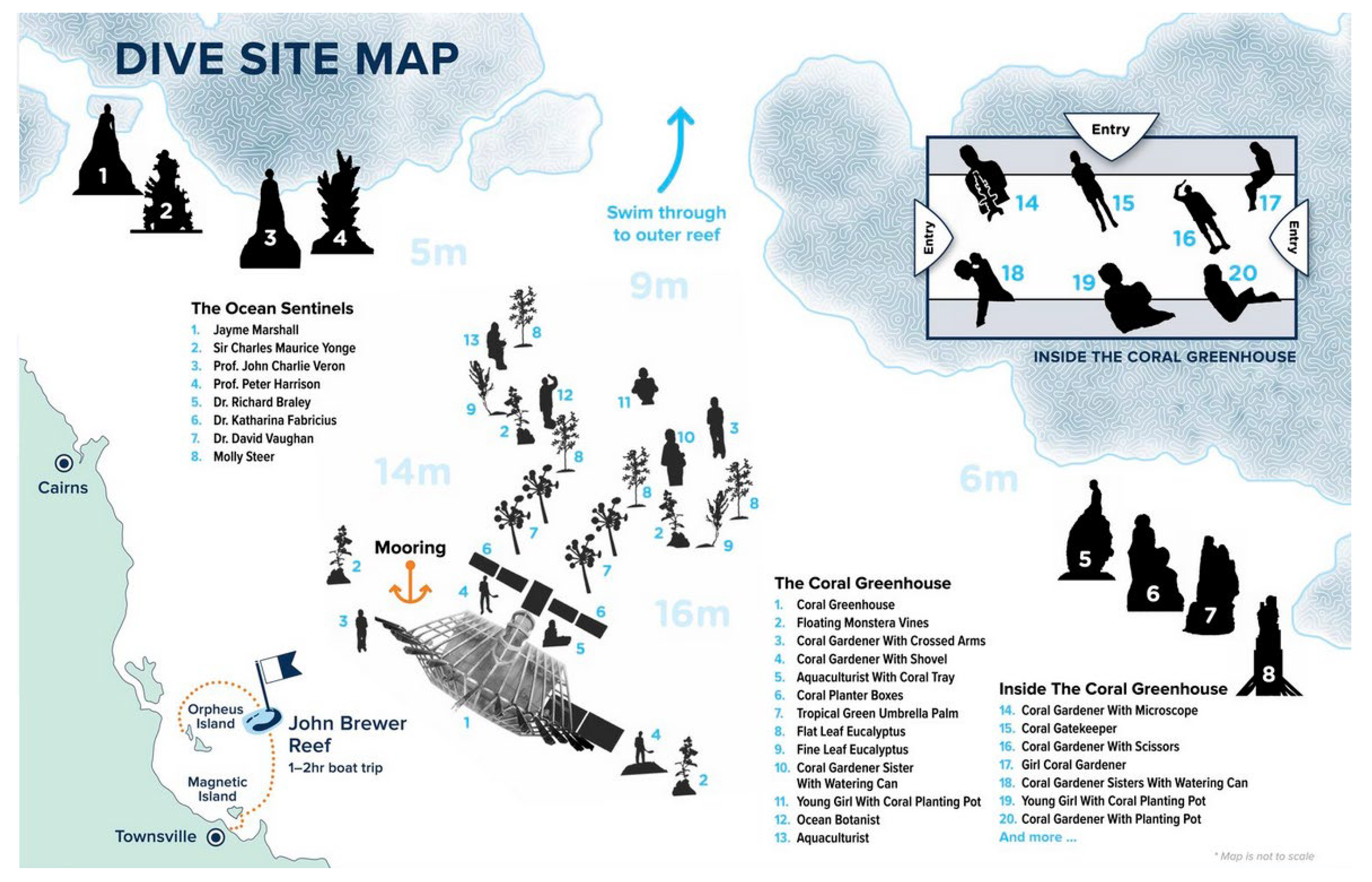

Award-winning sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor was commissioned by the MOUA to create three series of sculptures in and adjacent to Townsville and the Great Barrier Reef between 2017 and 2023 (

Figure 1). The three series of sculptures inspire a new perspective for the Great Barrier Reef and particularly focus on the fusion of art and science to communicate reef story-telling regarding changing climates represented by the Ocean Siren, coral reef restoration constituted by the Coral Greenhouse, and inspirational people who have contributed to the field of marine science research and ocean conservation by the Ocean Sentinels (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Core functions of the three series of sculptures that represent the Museum of Underwater Art.

Table 1.

Core functions of the three series of sculptures that represent the Museum of Underwater Art.

| | Ocean Siren | Coral Greenhouse | Ocean Sentinels |

|---|

| Location | The Strand, Townsville, Australia | John Brewer Reef, Central Great Barrier Reef—Australia | John Brewer Reef, Central Great Barrier Reef—Australia |

Core

Functions | The Ocean Siren, installed in 2019 near a jetty on The Strand, is a 4 m-high sculpture modeled on Takoda Johnson, a young member of the Wulgurukaba tribe. It connects to a live feed from an Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) weather station on Davies Reef and features 202 multi-colored LED lights that change color based on sea surface temperature. The color fluctuations highlight the impact of warming sea surface temperatures and the risks to coral reefs, serving as a warning about the threat to the Great Barrier Reef. | The Coral Greenhouse, installed in 2019 at John Brewer Reef, is a 12 m (H) × 9 m (L) × 6 m (W) stainless steel and concrete structure (Figure 1). It holds the Guiness world record for the largest underwater art structure and is based at a depth of 16m and rises to 6m beneath the surface. It offers an immersive perspective on the Great Barrier Reef and its ecology by exploring marine science, coral gardening, art, and architecture with the inclusion of 25 sculptures throughout its perimeter. | The Ocean Sentinels, installed in 2023, are a collection of eight sculptures of marine scientists and conservationists within the field of marine science (Figure 2). Each sculpture stands at 2.2 m tall and weighs between 1 and 3 tons. The sculptures are a unique blend of human figures and marine elements that symbolize the fusion of art and science. The sculptures have changed over time due to colonization of marine life (Figure 3) |

| Image | ![Sustainability 17 08359 i001 Sustainability 17 08359 i001]() | ![Sustainability 17 08359 i002 Sustainability 17 08359 i002]() | ![Sustainability 17 08359 i003 Sustainability 17 08359 i003]() |

2. Materials and Methods

The methods focus on the assessment of MOUA using Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, and Threat (SWOT) analysis and a benchmarking comparison of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). SWOT analysis is a simple and flexible management tool and provides significant benefits, such as reviewing strategic planning by revealing internal strengths and weaknesses alongside external opportunities and threats, leading to better-informed decision-making, improved competitive advantages, proactive risk management, and fostered teamwork. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are quantifiable measures used to evaluate the success of an organization or individual’s performance against specific objectives. The benefits of using KPIs include improving decision-making through data-driven insights, providing clarity and focus for strategic plans, motivating employees by setting clear goals and tracking progress, and enabling effective communication by creating a shared understanding of success. We measured 23 potential KPI’s (Year founded, Staff, Volunteers, First nations staff-volunteers, Volunteer hours, Partners, Tourism operators, Ambassadors/Guardians, Master reef guides, Revenue, Number of sculptures, Visitors, Citizen science observations, Coral cover (%), Corals planted/relocated, People engaged, People trained, Project and events, Carbon neutral events, Website reach, Media reach, Scientific papers, and Greenhouse gas emissions) to compare the MOUA with three organizations: Reef Authority, Great Barrier Reef Foundation and Queensland Museum.

3. Results

The Museum of Underwater Art is a ‘niche’ museum market with terrestrial and underwater infrastructure. The terrestrial infrastructure is free and accessible and has significant appeal to a broad market of people. MOUA’s Ocean Siren sculpture, and the message of ‘warming’ ocean temperatures through the perspective of traditional owners reaches more than 1.5 m views annually. Since its installation in late 2019 it has influenced many millions of locals and visitors to Townsville. The underwater infrastructure, such as the Coral Greenhouse and Ocean Sentinels, requires visitors to have a baseline level of in-water snorkeling or diving competence. Since its launch in 2020, just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Coral Greenhouse has attracted 12,000 divers on commercial tourism vessels, an estimated further 12,000 divers on recreational vessels, and a media audience of 250 m through over 100 publications and television productions.

Similarly to other Australian Museums, MOUA has proven, through its reach into local and global audiences, that it has the ability to influence conversations involving the Great Barrier Reef and reef conservation. MOUA commenced a citizen science project at John Brewer Reef in 2023 utilizing iNaturalist, a global online platform where individuals can contribute images and information about the observations they make of plants and animals towards research and conservation efforts. This project has since involved 287 people with over 6800 observations of 605 species [

13] (

Table 2).

The Museum of Underwater Art has also had ongoing coral restoration, site monitoring, and assessment projects to maintain continuous monitoring of the area. As a result of ongoing surveillance, MOUA reports significant coral reef growth and fish aggregations within the immediate area of the underwater coral greenhouse, ocean sentinel sculptures, and the surrounding reef habitat at John Brewer Reef. Since the MOUA was installed in 2019, several coral restoration projects have been undertaken and monitored over time which have been implemented to assess coral survivability and health on the structures. In March 2020 there were 131 corals of opportunity or broken pieces of live corals that were transplanted onto the MOUA structures (

Figure 4). These corals exhibited a survivorship of 91.6% after 12 months [

14]. In addition to this, corals of opportunity have been transplanted onto the sculptures post cyclone Kirrily in February 2024 and onto David Vaughan’s sculpture in June 2025. Natural coral recruits were also monitored in February 2022 on the Coral Greenhouse and January 2025 on the Ocean Sentinels (

Figure 4). Coral monitoring efforts have also assessed natural hard and soft coral recruitment onto the coral greenhouse and surrounding structures. The MOUA structure shows considerable natural recruitment of hard and soft corals, encrusting invertebrates, and continues to be monitored [

14].

Researchers have reshared 66 traditional owner Wulguru words to facilitate use of multiple languages for common species and activities [

15] (

Table 2).

During the feasibility work for the establishment of the MOUA, it undertook a significant fundraising effort from numerous partners and agencies including private sector partnerships, philanthropic foundations, and government bodies. This led to raising more than

$4 m and enabled the installation of the three series of sculptures. The values of each set of sculptures were as follows: the Ocean Siren valued at

$500 k, the Coral Greenhouse at

$2 m, and Ocean Sentinels at

$1.5 m. The source of Government investment was primarily tourism infrastructure funding that supported ‘regional’ locations to build initiatives that would attract a greater share of the visitor economy. The projected economic multiplier for MOUA was

$42 M in regional economic activity and created 182 (direct and indirect) jobs annually for the Townsville North Queensland community. The flow-on tourism impacts of this project are most remarkable, increasing tourism in the region by 50,000 visitors per annum [

16].

Since MOUA’s origin, it has had a significant impact on the involvement of the local community through education, science, art, and tourism [

17]. We utilize a SWOT analysis to understand the areas of strengths and the need for improvement (

Table 3).

We have compared the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for the Museum of Underwater Art with the Reef Authority [

18], Great Barrier Reef Foundation [

19,

20] and Queensland Museum [

21] (

Table 4). It is interesting to note that only six KPIs (year founded, staff, volunteers, first nations staff/volunteers, partners, revenue) were available for all four organizations. Two KPI metrics (volunteer hours, scientific papers) were measured by three organizations. Twelve KPIs were measured by two organizations. There were gaps where KPI metrics were not readily available including differences in KPI measurements such as media reach.

4. Discussion

Sustainability challenges are complex because they involve deeply intertwined environmental, social, political, and economic systems that operate within dynamic, changing global contexts, requiring fundamental transformations and systemic, integrative approaches to achieve a sustainable and resilient path. Key challenges include political, business and individual commitments associated with climate change, biodiversity loss, resource depletion, pollution, and socio-economic issues [

22]. Tackling these challenges requires communication with people at local and global scales and an integrated action focused approach that addresses key aspects of sustainability. The Museum of Underwater Art is innovative, nimble, and proactive in leading and actioning sustainable initiatives associated with artificial reefs, coral planting, citizen science, indigenous training and carbon neutral events to demonstrate and influence other organizations of what is possible and necessary to be more sustainable. An example of sustainability practice is that MOUA measures greenhouse gas emissions and facilitates carbon neutral events, however the three other reef organizations we assessed do not.

There and benefits and limitations in using different tools such as SWOT and key Performance Indicator (KPI) analysis. The limitations of SWOT include its vulnerability to internal biases and blind spots. Limitations of KPI analysis include poor data quality leading to misinformed decisions, an overemphasis on easily measurable but less strategic metrics, a narrow focus that ignores important contextual or long-term factors and difficulty in comparing between organizations.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for ocean sustainability should focus on both environmental health and socioeconomic impacts [

23]. Examples include coral reef coverage, ocean acidification levels, plastic pollution, fishing pressure on specific species, and the health of human communities reliant on the ocean. Our review of KPIs (

Table 4) included four relevant environmental indicators: Coral cover (%), Corals planted/relocated, Carbon neutral events, and Greenhouse gas emissions and 15 relevant socio-economic indicators: Staff, Volunteers, First nations staff/volunteers, Volunteer hours, Partners, Tourism operators, Ambassadors/Guardians, Master reef guides, Revenue, Visitors, Citizen science observations, People engaged, People trained, Website reach and Media reach. It is interesting to note the difference between the small number of environmental and large number of socio-economic indicators associated with the MOUA, Reef Authority, Great Barrier Reef Foundation, and Queensland Museum (

Table 4). One of the recommendations of this opinion piece is collaboration and consistency between government, businesses, and community organizations to compare sustainability indicators and performance. Additionally, the inclusion of KPIs is recommended for organizations and institutions to implement due to KPI’s abilities to proactively measure the effectiveness of sustainability within a functioning group and highlight areas of improvement.

How does MOUA measure sustainability? Firstly, with economic revenue. MOUA has introduced a new tourism industry supporting between 2 and 4 local dive businesses and generating approximately

$1m in direct sales for dive trips per year and an estimated indirect benefit of

$10m per year for travel, accommodation, and meals [

24]. A small proportion (

$15 per passenger, 4%) of direct gross tourism revenue is provided to the Museum of Underwater Art and is allocated to management, maintenance costs, and local events.

How does MOUA measure its environmental sustainability? One measure is through greenhouse gas emissions (GGE). MOUA’s GGE is estimated to be 527 tonnes per year and the other three organizations mentioned do not report annual GGE or the number of carbon neutral events. The direct impact of the MOUA Board and annual events is approximately 20 tonnes of GGE and this is offset to achieve a scope 1 carbon neutral outcome. The MOUA is recognized as a low impact tourism site on the Great Barrier Reef, with a capped number of 100 guests at the site at any one time. All tourism operators provide a dive briefing to visitors discussing the importance of reducing physical contact being made with corals and other forms of marine life, while promoting photos and videos to be taken of their surroundings. When the MOUA site is close to maximum capacity, there are both snorkelers and SCUBA divers who see different parts of the reef. Snorkelers stay at the surface away from the reef, while divers can pass beneath the sloping region of the site. The sustainability of underwater museums aligns with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 14, ‘Life below water’, and number 13, ‘Climate Action’.

The coral coverage at the MOUA site at John Brewer Reef in 2024 was 30–50% [

25]. This metric is consistent with average coral cover for the Great Barrier Reef. However, multiple disturbances such as crown-of-thorns starfish (CoTS), cyclones, and coral bleaching have greatly reduced coral cover from measurements within the range of 75–100% in 2017 [

25]. The use of coral coverage as a KPI is challenging for MOUA as there are limited local opportunities for maintaining coral health impacted by global disturbances. To promote and maintain coral health, the MOUA participates in small-scale coral restoration activities and events to increase the chances of coral survival following disturbances from cyclones. These restoration projects focused on relocating corals that were previously broken off from the reef via storm surges and wave action, and planting them onto the MOUA structures, providing a new home and potential for continued growth. Our promising coral survivorship and recruitment data suggest that underwater museums, such as the MOUA, can support reef restoration while simultaneously increasing awareness of these issues to the local community, having a great impact.

While many people care about environmental issues and support action, trust in the government to address them can vary. Studies suggest that trust in government, particularly concerning climate change, is often low, with fewer than 50% of respondents trusting their national or provincial governments on these issues [

26]. Environmental legislation, policies, and actions aimed at mitigating climate change ultimately rely on public knowledge and support. In an ideal world, community knowledge and climate action for coral reefs involves a multi-pronged approach where communities, governments, and other organizations work together to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve water quality, and restore degraded reefs.

Underwater museums, like the Museum of Underwater Art (MOUA) on the Great Barrier Reef, can play a crucial role in fostering environmental sustainability by creating artificial reefs, attracting marine life, and raising awareness about climate change, coral bleaching and reef conservation. With a media reach of 22,181,875; project reach of 250 M; and artist reach of 1 billion, the MOUA has a much larger audience than government and other NGO’s associated with coral reefs.

Museums such as MOUA that actively engage with their local communities, addressing their needs, interests, and feedback can assemble strong relationships and encourage a sense of ownership. Significant financial management and diverse funding streams are crucial for long-term success. Museums that prioritize educational programs and contribute to research influence a wider understanding and involvement of history, culture, and science. MOUA has a primary focus in its backyard; the Great Barrier Reef with an immense history encompassing numerous stories of people, culture from various aboriginal and present-day groups, and decades of dynamic advances in science, art and conservation. MOUA has developed a stimulating reef story for the communities of Townsville, which historically have relied on James Cook University, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, and ReefHQ to inform the community and visitors about reef stories. Despite the small staff and funding in comparison to other organizing bodies, we demonstrate that the influence in media reach, citizen science, and cultural engagement at a smaller level has the potential to be scaled up at larger institutions. These stories have been focused on research, management, and tourism, albeit important topics to incorporate, however involving local communities, proactive steps necessitating sustainability, and the impact individuals can make on such an incredible ecosystem is vital in creating purposeful changes to confront environmental impacts on the reef.

5. Future Directions

Governments and NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations) both offer benefits, but their advantages lie in different areas. Governments, with their broad mandate and significant resources, can implement policy change and large-scale, long-term projects, while NGOs often excel at providing targeted services and adapting to specific community needs. Governments primarily rely on taxpayer funding, while NGOs depend on donations, grants, and sometimes private funding. Governments are inherently influenced by political agendas, while NGOs strive to remain independent and non-partisan. Government organizations such as the Reef Authority are the backbone of marine management, providing legislation, policies, permits, and compliance, while NGOs such as the Great Barrier Reef Foundation and MOUA are the dynamic, agile force that can address specific needs and innovate solutions, often working in collaboration with the government, business, and community to achieve broader social goals.

- 2.

Resources

The organizations that are well known in Great Barrier Reef research and education are relatively large with 55–419 staff and budgets of 66 to 112 million. In comparison the MOUA has finite resources and relies on volunteers and the local community. MOUA has the potential to grow their resources primarily by increasing the number of visitors in Townsville and obtain new partnerships and sponsorships with local businesses.

- 3.

Collaborative partnerships for reef sustainability

MOUA successfully collaborated with leading governments, traditional owners, science, community, business, and management organizations during the design and installation phase of the three series of structures. During the operational phase there are formal collaborations with tourism operations and Reef Ecologic for citizen science and monitoring. Future collaborations could leverage the easy access MOUA has to the John Brewer reef location. Short and simple scientific expeditions require OH&S compliance, expensive equipment, extensive planning, and dedicated resources; in contrast, tourism operators provide regular, cheap and safe transport options. Scientific work at the MOUA site is an easy access option for our scientific partners.

- 4.

Transition from tourism to education

MOUA’s reef experience is based on commercial vessels undertaking day trips with tourists from Townsville, Magnetic Island, and international influxes. A range of verbal and printed material is available on these commercial vessels, and there is a clear synergy between tourism and education. Successful tourism operators create positive experiences while engaging the local communities. Successful education results in providing individuals with useful knowledge, skills, and opportunities for their personal and professional growth. Trip Advisor indicates the satisfaction of the tourism experience as 4.4–4.8 out of 5 which is consistent with a social survey of 8.7 out of 10 [

14].

The MOUA innovation of partnering with traditional owners to share cultural knowledge on names of common species such as coral (dhambi), fish (guya), clam (gubiru), seaweed (bugurga), shark (bururu), and whale (dugara) has resulted in many co-benefits including knowledge, art, jobs, reports on the sea country, and scientific papers [

15,

27,

28].

- 5.

The influence of museums and their role in fostering environmental awareness

Museums have been a place of congregation by connecting ideas, preserving ecological organisms, expanding upon problems relating to societal topics, and showcasing other types of human collections to share history, culture, and intent of previous generations. Such influences of museums, both terrestrial and marine based, can be a place of influence for future generations [

29]. Museums provide an environment that permits visitors to experience and learn about concepts in a neutral manner. Such space allows for the development of environmental awareness, education for the masses, and interactive programs for students. The involvement of individuals and discussions amongst various problems and solutions for different fields of study can encourage headway towards communal and collective change [

30].

The role of an underwater museum is a unique interface between art and science and promoting marine conservation. While scientific methodologies grounded in empirical evidence provide the foundation for understanding ecological processes, emotional and cultural engagement are equally crucial in shaping conservation outcomes. By employing artistic expression in an underwater setting, the museum creates a platform where environmental awareness is not only informed by data but also inspired by aesthetic and spiritual experience.

Human beings interpret the world through both rational analysis and emotional intuition. Decisions—ranging from personal relationships to societal values—are often driven as much by feeling as by fact. Within environmental discourse, however, scientific narratives tend to dominate. While essential for identifying problems and proposing solutions, science alone may fail to motivate the emotional engagement needed for widespread behavioral change. Recognizing this, the underwater museum model leverages the complementary strengths of art and science. They can serve as cultural artifacts that connect individuals to the marine environment, rekindling a sense of reverence and responsibility toward nature.

The global shift toward industrialization, urban living and capitalist consumption has progressively distanced humans from the natural world. In parallel, digital technologies have reshaped the way people interact with reality, especially among younger generations. This detachment poses a challenge to conservation, which requires both ecological understanding and emotional investment.

Museums have long served as institutions for cultural transmission and collective memory. Terrestrial museums curate and elevate objects deemed valuable, conferring upon them a sense of worth and significance. Applying this same logic underwater, an aquatic museum reframes the marine environment as a sacred and culturally significant space. The underwater museum thus becomes more than an exhibition—it is a symbolic and experiential declaration that the ocean and its inhabitants are of irreplaceable value. Visitors often report feelings of awe, introspection, and inspiration after interacting with the installations. The figurative nature of the sculptures reinforces the idea that humans are not apart from nature but part of it—an important psychological reframing that aligns with holistic conservation ethics. Furthermore, by distilling complex ecological issues into accessible artistic narratives, the museum serves as an effective educational platform. It fosters not only awareness but also empathy, bridging the gap between scientific data and lived experience.

- 6.

The journey to sustainability

It is no longer enough for museums to simply serve as monuments to preservation—they must now focus on conservation, sustainability, and communication [

31]. Institutions such as MOUA now have a global responsibility for leadership in sustainability and climate mitigation and actions.

More broadly, MOUA has helped create a global network of museum-adjacent projects and as a result positions itself within a new vanguard of tourism experience which is centered on education and connection. These other projects can be found in Mexico, Museo Subacuático de Arte (MUSA); Spain, Museo Atlántico; Cyprus, Cyprus Museum of Underwater Sculpture Ayia Napa (MUSAN); France, Cannes Underwater Eco-Museum; and Miami, The Reef Line. New research and modeling [

32] predict that an ongoing “extinction of experience” with nature connectedness is now accepted as a key root cause of the environmental crisis, creating nature-based experiences that have been at the forefront of these networks of museums. It is increasingly recognized that threats to the oceans are global in scale, and that a worldwide network of museums is well placed to form alliances and tell a shared global story.

Siddig and Freundt [

11] reported that an underwater museum can foment a more profound connection between the Qatar community and tourists with the country’s marine environment while supporting economic diversification through sustainable tourism and contributing to the 2030 Qatar National Vision and the 14th United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) on life below water.

The first step for sustainability is to move from a vision to measuring the details (such as Greenhouse Gas emissions, waste), report it, and then take action to reduce and offset. There are limited carbon calculators for vessels, but the total volume and type of fuel is easy to calculate. A day trip vessel to MOUA uses between 700 and 1000 L of diesel fuel. MOUA’s Board is a leader in carbon neutral not-for-profit management as travel and events are purposefully measured and offset. A future local challenge is to ensure that tourism operators who travel to the MOUA site also measure and offset their impacts. We acknowledge that this is possible through voluntary carbon offsets by tourism businesses or future mandatory agreements between MOUA and certified tourism operators. MOUA has a strong relationship with Reef Ecologic who ensures that their travels, associated with individual or group citizen science activities, are carbon neutral and independently assessed by BCorp accreditation.