VFR Travel: A Sustainable Visitor Segment?

Abstract

1. Introduction

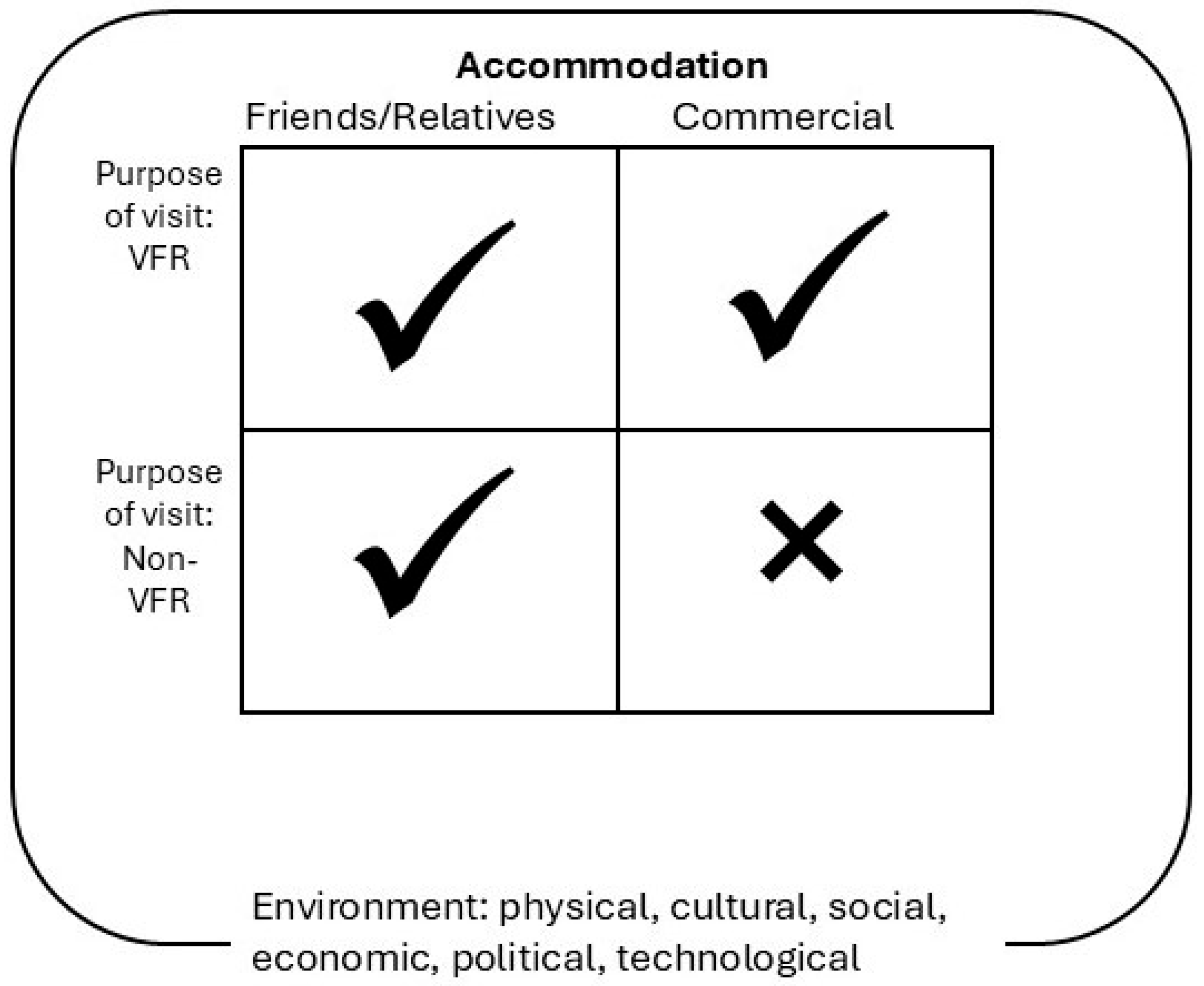

2. Literature Review

2.1. Climate Change and Tourism

2.2. Quality of Life

2.3. VFR Travel

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zentveld, E.; Labas, A.; Edwards, S.; Morrison, A.M. Now Is the Time: VFR Travel Desperately Seeking Respect. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable Tourism: A State-of-the-Art Review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The Impact of Tourism on the Physical Environment. Ann. Tour. Res. 1978, 5, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeril, M. Tourism and the Environment—Accord or Discord? Tour. Manag. 1989, 10, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, B.R. The Brundtland Report: “Our Common Future”. Med. War. 1988, 4, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Mehrotra, A.; Mishra, A.; Rana, N.P.; Nunkoo, R.; Cho, M. Four Decades of Sustainable Tourism Research: Trends and Future Research Directions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prerana, P.; Kapoor, D.; Jain, A. Sustainable Tourism and Its Future Research Directions: A Bibliometric Analysis of Twenty-Five Years of Research. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 541–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. Why Sustainable Tourism Must Address Climate Change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. Can Sustainable Tourism Survive Climate Change? J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Cavanagh, J.-A. Energy Efficiency Trend Analysis of the Tourism Sector; No. August; Landcare Research: Lincoln, New Zealand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Becken, S. An Integrated Approach to Travel Behaviour with the Aim of Developing More Sustainable Forms of Tourism; Landcare Research Internal Report LC0304/005, No. August; Landcare Research: Lincoln, New Zealand, 2003; pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, T. Visiting Friends and Relatives Tourism and Implications for Community Capital. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2013, 5, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Greene, D. Research for Environmentally Sustainable Tourism—All Talk, No Action? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 62, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.-P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The Carbon Footprint of Global Tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Analytics. Australia’s Massive Global Carbon Footprint Set to Continue with Fossil Fuel Exports. Available online: https://climateanalytics.org/press-releases/australias-massive-global-carbon-footprint-set-to-continue-with-fossil-fuel-exports (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Climate Analytics. Australia’s Global Fossil Fuel Carbon Footprint. 2024. Available online: https://ca1-clm.edcdn.com/publications/Aust_fossilcarbon_footprint.pdf?v=1723409920 (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Ukpanah, I. Can the Large Cruise Ships Drive Systemic Change in Maritime Sustainability? Green Match. Available online: https://www.greenmatch.co.uk/blog/maritime-sustainability (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Dolnicar, S.; Knezevic Cvelbar, L.; Grün, B. Changing Service Settings for the Environment: How to Reduce Negative Environmental Impacts without Sacrificing Tourist Satisfaction. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M. How Often Should You Wash and Change Your Towel? BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-66735226 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Gavin, R. Aussies Reveal How Often They Wash—And Hopefully Change—Their Sheets. Nine.com.au. Available online: https://honey.nine.com.au/living/how-often-do-people-wash-their-sheets-australia-exclusive-nine-poll/392a2c7f-2f0c-4319-9d2e-3ec5e5d85dd3 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Boyle, C.C. How Often Should You Wash Your Sheets? The Answer Might Surprise You. USA Today. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/health-wellness/2024/05/30/how-often-should-you-wash-your-sheets/73646184007/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Greene, D.; Zinn, A.; Demeter, C.; Dolnicar, S. “Hi, I’m Terri Towel. Please Reuse Me” Can Anthropomorphising Towels Prompt Tourists to Reuse Them? SocArXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. Understanding GSM in Towels: Your Guide to Buying the Best Bath Towel. Fine Linen & Bath. Available online: https://flandb.com/blogs/by-flandb/understanding-gsm-in-towels-your-guide-to-buying-the-best-bath-towel?srsltid=AfmBOoodtAxHuuOvNfVvlMu6gNwZFKuN-om5F1wo_qzRsl9MHt7qHETe (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- International Tourism Partnership. Water Stewardship For Hotel Companies; International Tourism Partnership: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Backer, E. VFR Travel: Do Visits Improve or Reduce Our Quality of Life. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Berbekova, A.; Kim, H. Designing for Quality of Life. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Önder, I.; Uysal, M. Smart Tourism Destination (STD): Developing and Validating an Impact Scale Using Residents’ Overall Life Satisfaction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 2849–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. Quality of Life (QOL) and Well-Being Research in Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S. Rating Places: A Geographer’s View on Quality of Life; Association of American Geographers: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U.; Koo, C. Smart Tourism Cities: A Duality of Place Where Technology Supports the Convergence of Touristic and Residential Experiences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebicki, M. Most Disliked Tourists by Country Revealed in New Research. The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 September 2019. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/traveller/reviews-and-advice/most-disliked-tourists-by-country-revealed-in-new-research-20190918-h1i4qq.html (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Zentveld, E.; Yousuf, M. Does Destination, Relationship Type, or Migration Status of the Host Impact VFR Travel? Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, A.G.; Ramirez, A.R.M. Influence of VFR Tourism on the Quality of Life of the Resident Population. J. Tour. Serv. 2020, 11, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Hunter, W.C.; Chung, N. Smart Tourism City: Developments and Transformations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Tung, V.W.S. Understanding Residents’ Attitudes towards Tourists: Connecting Stereotypes, Emotions and Behaviours. Tour. Manag. 2022, 89, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meis, S.; Joyal, S.; Trites, A. The US Repeat and VFR Visitor to Canada: Come Again, Eh! J. Tour. Stud. 1995, 6, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Becken, S.; Simmons, D.G.; Frampton, C. Energy Use Associated with Different Travel Choices. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.Y.; Morrison, A.M.; O’Leary, J.T. Does the Visiting Friends and Relatives’ Typology Make a Difference? A Study of the International VFR Market to the United States. J. Travel. Res. 2001, 40, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, A.; Palmer, C. Understanding VFR Tourism Behaviour: The First Five Years of the United Kingdom Tourism Survey. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, E. VFR Travel: Why Marketing to Aunt Betty Matters. In Family Tourism: Multidisciplinary Perspectives; Schänzel, H., Yeoman, I., Backer, E., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Beioley, S. Four Weddings, a Funeral and a Holiday—The Visiting Friends and Relatives Market. Insights 1997, 8, B1–B15. [Google Scholar]

- Backer, E. VFR Travel—An Examination of the Expenditures of VFR Travellers and Their Hosts. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, E.; Erol, G.; Düşmezkalender, E. VFR Travel Interactions through the Lens of the Host. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, M.; Backer, E. Hosting Friends versus Hosting Relatives: Is Blood Thicker than Water? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunlich, C.; Nadkarni, N. The Importance of the VFR Market to the Hotel Industry. J. Tour. Stud. 1995, 6, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Backer, E. Opportunities for Commercial Accommodation in VFR. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, E. VFR Travel: It Is Underestimated. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, T.; Nunkoo, R. Paid Accommodation Use of International VFR Multi-Destination Travellers. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, E. VFR Travel: Its True Dimensions. In VFR Travel Research: International Perspectives; Backer, E., King, B., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A.J.; Harris, N.G. Mode Choice for VFR Journeys. J. Transp. Geogr. 1998, 6, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington-Gray, L. Understanding the Domestic VFR Drive Market in Florida. J. Vacat. Mark. 2003, 9, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, E. VFR Travel: An Assessment of VFR versus Non-VFR Travellers. Ph.D. Thesis, Southern Cross University, Lismore, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L.; Seetaram, N.; Forsyth, P.; King, B. Is the Migration-Tourism Relationship Only about VFR? Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, M.; Backer, E. A Content Analysis of Visiting Friends and Relatives (VFR) Travel Research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2015, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, T. Research Note: A Content Analysis of Articles on Visiting Friends and Relatives Tourism, 1990–2010. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 781–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, L.; Choi, S. Place Attachment Expressed by Hosts and Guests Visiting Friends and Relatives and Implications for Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiper, N. The Framework of Tourism: Towards a Definition of Tourism, Tourist, and the Tourist Industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, E. VFR Travelers: How Long Are They Staying? Tour. Rev. Int. 2011, 14, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Kaspar, C.; Schmidhauser, H.; Keller, P.; Bieger, T. Editorial 80 Years of Tourism Review—Transformative and Regenerative Power of Smart Tourism. Tour. Rev. 2025, 80, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toli, A.M.; Murtagh, N. The Concept of Sustainability in Smart City Definitions. Front. Built Environ. 2020, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zentveld, E. VFR Travel: A Sustainable Visitor Segment? Sustainability 2025, 17, 5558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125558

Zentveld E. VFR Travel: A Sustainable Visitor Segment? Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125558

Chicago/Turabian StyleZentveld, Elisa. 2025. "VFR Travel: A Sustainable Visitor Segment?" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125558

APA StyleZentveld, E. (2025). VFR Travel: A Sustainable Visitor Segment? Sustainability, 17(12), 5558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125558