Abstract

Oil palm cultivation plays a critical role in rural livelihoods in Indonesia, yet previous research has often overlooked systematic institutional differences among smallholders. This study aims to analyze disparities in assets, strategies, and livelihood outcomes among three oil palm smallholder typologies—ex-Perkebunan Inti Rakyat (PIR) transmigrant smallholders who received land through government transmigration programs, independent smallholders who cultivate oil palm without formal partnerships, and plasma smallholders operating under corporate partnership schemes—in Central Mamuju Regency, West Sulawesi. A descriptive quantitative approach based on the sustainable livelihoods framework was employed, using chi-square analysis of data collected from 90 respondents through structured interviews and field observations. The results show that ex-PIR smallholders possess higher physical, financial, and social capital and achieve better income and welfare outcomes compared to independent and plasma smallholders. Independent smallholders exhibit resilience through diversified livelihood strategies, whereas plasma smallholders face asset limitations and structural dependency on partner companies, increasing their economic vulnerability. The study concludes that differentiated policy approaches are necessary to enhance the resilience of each group, including improving capital access, promoting income diversification, and strengthening institutions for plasma smallholders. Future research should expand geographical scope and explore factors such as technology adoption, gender dynamics, and intergenerational knowledge transfer to deepen understanding of sustainable smallholder livelihoods in tropical plantation contexts.

1. Introduction

Oil palm is a vital plantation commodity that significantly contributes to Indonesia’s economy, particularly for employment and foreign exchange revenue [1,2]. In West Sulawesi, specifically in the Central Mamuju Regency, the expansion of oil palm plantations has transformed the agricultural landscape and community livelihood structure, particularly following the initiation of the PIR transmigration program in the 1980s. This expansion has continued to evolve, increasing in scale and complexity to the present day [3,4]. The PIR program is a partnership framework between major enterprises and smallholders, wherein firms manage and cultivate plantation land, while smallholders administer a designated region and remit rent proportional to the managed expanse. This development has resulted in three distinct typologies of oil palm smallholder: ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders, independent smallholders, and plasma smallholders, each possessing unique characteristics facing specific challenges in improving livelihood resilience.

Previous studies on oil palm smallholders in Indonesia have primarily focused on technical aspects of production [1,5,6,7], environmental impacts [8,9,10], or policy analysis [11,12,13]. However, research examining livelihood differentiation among oil palm smallholders remains limited, with studies treating them as a homogeneous group despite evidence of systematic institutional and socio-economic variations. Studies on coconut smallholders in Gorontalo, Indonesia [14], and maize smallholders in South Sulawesi (Indonesia) [15] revealed that smallholders exhibit diverse characteristics in terms of resource availability and social networks. Furthermore, the role of historical institutional arrangements—such as transmigration programs and corporate partnership schemes—in creating distinct livelihood trajectories among smallholder typologies has received insufficient attention in the literature. Smallholders’ social capital—which includes bonding (relationships with fellow smallholders), bridging (networks with similar groups), and linking (connections with individuals of higher socio-economic status)—plays a crucial role in shaping their livelihood opportunities. Disparities in access to social capital affect smallholders’ ability to secure resources, participate in collective decision making, and reduce transaction costs in their agricultural activities. Yet, empirical evidence demonstrating statistically significant differences in asset portfolios, adaptive strategies, and economic outcomes across institutionally differentiated smallholder groups remains scarce.

Although the expansion of oil palm plantations has significantly transformed rural socio-economic structures in Indonesia, most previous studies tend to treat smallholders as a homogeneous group. This approach overlooks the critical variations in livelihood asset access, adaptive strategies, and economic outcomes across different smallholder typologies. In reality, distinctions among ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders, independent smallholders, and plasma smallholders have profound implications for household economic resilience, social inequality, and long-term livelihood sustainability. Therefore, a more focused analysis is necessary to understand how these typological differences shape livelihood systems.

To address this gap, this study contributes by providing empirical evidence with statistical validation of differences in livelihood assets, adaptive strategies, and livelihood outcomes among three oil palm smallholder typologies in the Central Mamuju Regency, West Sulawesi, using a descriptive quantitative approach grounded in the sustainable livelihoods framework. Through systematic measurement and chi-square analysis across multiple livelihood dimensions, this research demonstrates how historical institutional arrangements (PIR transmigration programs and plasma partnerships) create statistically significant disparities in asset accumulation, strategy implementation, and economic outcomes. It sheds light on how differential access to livelihood capitals and institutional arrangements (PIR programs and plasma partnerships) create distinct pathways of resilience or vulnerability, thereby enriching the academic understanding of livelihood dynamics in tropical plantation contexts with robust quantitative evidence of smallholder heterogeneity.

This study contributes by investigating disparities in livelihood asset attributes—including natural, human, social, physical, and financial capital—as well as livelihood strategies and outcomes among ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders, independent smallholders, and plasma smallholders in the Central Mamuju Regency. Specifically, this research seeks to determine how variations in ownership and access to livelihood capital influence the strategies and outcomes of different smallholder types through empirical measurement and comparative analysis.

This study integrates multiple theoretical perspectives to analyze livelihood dynamics among oil palm smallholders. While the sustainable livelihood framework developed by Chambers and Conway [16] provides the foundational structure, examining the interrelationships between assets, strategies, and outcomes, we enhance this framework through contemporary theoretical lenses. We integrate Scoones’ [17,18] more recent work on sustainable livelihoods, which emphasizes the role of political economies and power relationships in shaping resource access and livelihood trajectories. This integrated theoretical approach enables us to develop specific quantitative metrics and statistical testing procedures to systematically compare: (1) asset portfolios—measured through quantifiable indicators of land ownership patterns, physical capital quality, human capital development, social capital networks, and financial capital accumulation; (2) strategy implementation—assessed through quantified responses to market shocks, adaptation mechanisms, and accumulation approaches; and (3) livelihood outcomes—evaluated through measurable economic returns, sustainability indicators, and household welfare measures. This operationalization of theoretical concepts into measurable variables enables systematic comparison among the three smallholder typologies to reveal how institutional arrangements and historical contexts shape diverse livelihood trajectories within oil palm plantation communities.

2. Materials and Methods

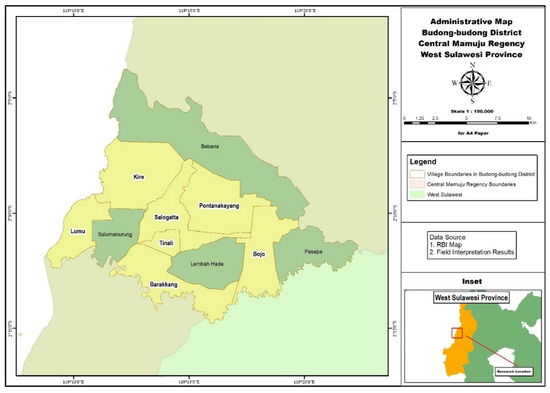

This research employs a quantitative descriptive approach to analyze variations in asset ownership, strategies, and livelihood outcomes among three typologies of oil palm smallholders in the Central Mamuju Regency [19]. The research location was selected through purposive sampling in Budong-Budong District, Central Mamuju Regency, West Sulawesi Province, encompassing seven villages: Salugatta, Tinali, and Pontanakayyang (representing ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders); Kire, Lumu, and Barakkang (representing independent smallholders); and Bojo Village (representing plasma smallholders) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research Location Map.

The research involved a total of 90 respondents, with 30 respondents representing each oil palm smallholder typology. Respondent selection was conducted using purposive sampling based on established inclusion criteria [20]. This sample size is consistent with recommendations for research employing comparative descriptive analysis in rural livelihood studies [21,22]. For ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders, the criteria used were farmers who own oil palm land as a result of the PIR transmigration program and have managed such land for a minimum of 10 years. For independent smallholders, the criteria used were farmers who own and manage oil palm land independently without formal partnerships with companies. As for plasma smallholders, the criteria used were farmers affiliated with the partnership scheme of PT. Wahana Karya Sejahtera Mandiri (PT WKSM). To ensure representativeness, respondents were selected considering variations in land ownership size, crop age, and land location in each village.

Primary data collection was conducted through structured interviews using questionnaires that covered livelihood capital variables (natural, physical, human, social, and financial), livelihood strategies, and livelihood outcomes [16,23]. Direct observation was also conducted to observe land conditions, settlements, and farmers’ socio-economic activities [24].

Data were analyzed descriptively by calculating frequency distributions and percentages to illustrate differences in livelihood capital characteristics, livelihood strategies, and livelihood outcomes among the three farmer typologies. To validate the observed descriptive patterns, chi-square tests of independence were conducted to examine whether differences in categorical variable distributions across smallholder typologies were statistically significant [25,26]. Livelihood capital was assessed based on quantity, quality, and accessibility, while livelihood strategies were evaluated from aspects of risk management, adaptation, and accumulation. Livelihood outcomes were evaluated from economic income, sustainability, and household welfare. To maintain data validity, cross-checking between information sources was conducted through simple triangulation techniques [21,27].

3. Results

Oil palm is a key plantation crop and a vital source of income for communities in the Central Mamuju Regency, West Sulawesi Province, particularly in Budong-Budong District. Initially, oil palm plantations were integrated into the PIR transmigration program, which established several transmigration settlement units (TSUs) in 1993, including those in Budong-Budong District, such as TSUs Salugatta, Pontanakayyang, and later, Tinali Village. Following the socio-economic benefits derived from oil palm cultivation in these transmigrant villages, nearby communities in Kire, Lumu, and Barakkang, which observed these transformations, began independent oil palm farming in 1998, primarily involving local residents. Subsequently, communities from outside Budong-Budong District and the Central Mamuju Regency engaged in oil palm cultivation through plasma schemes in collaboration with PT Wahana Karya Sejahtera Mandiri (PT WKSM). Under this scheme, local smallholders allocated portions of their land for management by the company. This historical trajectory led to the emergence of three distinct typologies of oil palm smallholders in Budong-Budong District, each characterized by differences in livelihood assets, strategies, and outcomes, as outlined in the following section.

3.1. Livelihood Assets

The livelihood assets of smallholders in the Central Mamuju Regency vary significantly across three typologies: ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders, independent smallholders, and plasma smallholders. All smallholders fall within the productive age range of 26 to 60 years, with a male predominance across all categories. Notably, plasma smallholders account for only 16.7% of total smallholder participation, particularly within the Mandar ethnic minority, which adheres to the Siwalli Parri cultural principle—emphasizing equitable responsibilities between spouses in sustaining the household. Educational attainment also varies across groups. Ex-PIR transmigrant and independent smallholders generally have higher education levels, with 20% and 10% university graduates, respectively, and 43.3% and 66.7% high school graduates. In contrast, plasma smallholders exhibit lower educational attainment, with 50% having only completed elementary school. These differences significantly impact farming management skills and access to resources.

Material well-being further reflects these disparities. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders report higher welfare levels, with 60% owning permanent residences and 73.3% possessing automobiles and motorcycles. These findings highlight income inequality and uneven access to productive resources among the three smallholder groups.

3.1.1. Natural Capital

Natural capital plays a crucial role in assessing the quality and quantity of natural resource stocks utilized by communities for their livelihoods. In Budong-Budong District, land ownership patterns among oil palm smallholders differ significantly across the three typologies: Ex-PIR transmigrant, independent, and plasma smallholders. These differences are detailed in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 and elaborated below.

Table 1.

Average Oil Palm Land Ownership in Budong-Budong District (Source: Field Interview Results).

Table 2.

Average Non-Oil Palm Agricultural Land Ownership in Budong-Budong District (Source: Field Interview Results).

Table 3.

Average Non-Agricultural Land Ownership in Budong-Budong District (Source: Field Interview Results).

The land ownership patterns of oil palm producers in Budong-Budong District demonstrate distinct characteristics. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders benefit from land allocations under the government’s transmigration program, receiving 3 hectares per household (Table 1): 2 hectares of primary farmland, 0.75 hectares for secondary agriculture, and 0.25 hectares for residential yards. Among them, 50% own 1–2 hectares of oil palm land, 20% own 2–4 hectares, 10% own 4–6 hectares, 13.3% own 6–8 hectares, and 6.7% own more than 8 hectares. Statistical analysis confirmed that these land ownership distribution patterns differ significantly across the three smallholder typologies (χ2 = 27.099, df = 12, p = 0.007).

Independent smallholders, mostly indigenous to Budong-Budong District, acquired their land by cultivating public land that was subsequently acknowledged as privately owned. Data indicate that 40% possess 1–2 hectares of oil palm land, 23.3% own 2–4 hectares, 16.7% have 0.5–1 hectares, 10% control 4–6 hectares, 6.7% possess 6–8 hectares, and 3.3% own land over 8 hectares.

Next, plasma smallholders in the Bojo community, which is an expansion community from Tinali Village, demonstrate different land ownership patterns from the other two groups of smallholders: 50% of plasma smallholders own oil palm land measuring 0.5–1 hectares, 40% own 1–2 hectares, and 10% hold 2–4 hectares. No plasma smallholders possess oil palm land over 4 hectares, signifying a reduced business scale relative to ex-PIR transmigrant and independent smallholders.

Unlike other smallholder groups, ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders no longer possess non-oil palm agricultural land (Table 2). This signifies their specialization plan on oil palm agriculture, perceived as more lucrative than crop diversification. This decision seems to stem from their observation of substantial welfare enhancements resulting from oil palm yields, thereby motivating them to maximize the cultivation of this crop on all their owned property.

In contrast to ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders, independent smallholders continue to uphold land diversification by allocating spaces for non-oil palm production. Data indicate that 33.3% possess less than 0.5 hectares of non-oil palm land, 26.7% possess 0.5–1 hectares, 10% possess 1–2 hectares, and 30% possess more than 2 hectares. This area is utilized for cultivating many commodities, including corn, bananas, coconuts, and cocoa, exemplifying a crop diversification strategy to mitigate the risk of reliance on a singular item.

Regarding non-oil palm land ownership, 30% of plasma smallholders possess less than 0.5 hectares, 40% own between 0.5 and 1 hectare, and 10% own between 1 and 2 hectares. This property is utilized for the cultivation of commodities including corn, bananas, and oranges. This crop diversification pattern demonstrates a technique to sustain supplementary revenue sources in conjunction with oil palm production. The observed differences in non-oil palm agricultural land ownership patterns among the three groups were statistically significant (χ2 = 106.200, df = 8, p < 0.001), confirming the distinct diversification strategies employed by each smallholder typology.

Housing land ownership among ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders also reflects favorable conditions (Table 3), with 56.7% owning 150–200 m2, 26.7% owning 100–150 m2, and 16.7% possessing more than 200 m2. The prevalence of extensive land ownership suggests stronger economic capacity and investment in residential properties. This pattern underscores their adaptation strategy, prioritizing oil palm cultivation over other land uses to maximize economic returns.

Among non-agricultural landowners, namely in dwellings, 50% of independent smallholders possess 100–150 m2 of land, 20% possess 150–200 m2, and 30% possess more than 200 m2. Among non-agricultural landowners, namely in dwellings, 50% of independent smallholders possess 100–150 m2 of land, 20% possess 150–200 m2, and 30% possess more than 200 m2. Additionally, several farmers maintain fish ponds as supplementary non-agricultural assets. Among the three farmer typologies, only independent smallholders possess fish ponds, with 26.7% owning ponds of 0.5–1 hectare in size and 16.7% owning ponds larger than 1 hectare. Meanwhile, 56.7% of independent smallholders do not own fish ponds. None of the plasma smallholders possess fish ponds, and neither do any of the ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders. This varied land ownership pattern illustrates independent smallholders’ adaptive strategies for sustaining several revenue sources and enhancing household economic resilience.

In terms of non-agricultural land ownership, specifically houses, the majority (66.7%) of plasma smallholders possess land ranging from 100 to 150 m2, whereas 16.7% own land extending between 150 and 200 m2, and another 16.7% own land beyond 200 m2. Data indicates that none of the plasma smallholders has fish ponds, in contrast to independent smallholders who partially own fish ponds as supplementary revenue sources. Chi-Square analysis validated that residential land ownership patterns also differ significantly among the three smallholder groups (χ2 = 16.254, df = 4, p = 0.003).

The land ownership attributes of plasma smallholders are intrinsically linked to their status as newcomers who cultivated new land and formed partnerships with PT WKSM. This collaboration framework grants them access to oil palm plantation growth but within a more restricted area. Nevertheless, they continue to practice agricultural diversification by employing non-oil palm land, demonstrating an understanding of the significance of alternate revenue streams and family food security.

The choice to sustain this land diversification seems to be shaped by their experience as indigenous inhabitants who recognize the significance of avoiding dependence on a singular commodity. This technique offers them adaptability in responding to oil palm price volatility and evolving market conditions while ensuring family food security through the cultivation of food crops.

3.1.2. Physical Capital

Physical capital across the three groups of oil palm growers in Budong-Budong District exhibits notable disparities (Table 4), especially regarding dwelling quality and car ownership. Research indicates that ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders possess superior living circumstances, with 60% residing in permanent structures, 30% in semi-permanent dwellings, and merely 10% in non-permanent or stilt buildings. This advantage signifies their superior economic capacity to invest in enhancing housing quality. In contrast, independent smallholders have a more equitable distribution of housing conditions, comprising 40% permanent buildings, 26.7% semi-permanent houses, and 33.3% non-permanent or stilt houses. Plasma smallholders exhibit the lowest percentage of permanent residences at 36.7%, with 20% classified as semi-permanent, and the highest percentage of non-permanent or stilt dwellings at 43.3%. These disparities signify a divergence in economic capacity and investment objectives among the three agricultural groups.

Table 4.

Physical Capital Ownership in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

In terms of vehicle ownership, a comparable trend is evident. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit the highest vehicle ownership, with 73.3% possessing both motorcycles and cars, while 26.7% own only motorcycles. Independent smallholders occupy a median position, with 53.3% owning both motorcycles and cars and 46.7% owning solely motorcycles. Plasma smallholders demonstrate the lowest ownership, with only 36.7% owning both motorcycles and cars, while the majority (63.3%) possess only motorcycles.

These disparities in physical capital ownership reflect differences in welfare levels and economic capabilities among the three smallholder groups. This also illustrates how variations in resource access and asset management strategies can influence the standard of living and socio-economic mobility of each smallholders group in Budong-Budong District. Statistical analysis indicated that while differences in living conditions approached significance (χ2 = 8.783, df = 4, p = 0.067), vehicle ownership patterns showed similar distributional trends across the three smallholders typologies.

3.1.3. Human Capital

The human capital of the three groups of oil palm smallholders in Budong-Budong District exhibits notable disparities in educational attainment and training (Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7).

Table 5.

Education Level of the Head of Neighborhood Association of Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

Table 6.

Education Level of the Children of Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

Table 7.

Training Attended by Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders possess the highest educational attainment, with 10% holding university degrees, 40% having completed high school, 20% graduating from junior high school, and 30% finishing elementary school (Table 5). This elevated educational attainment correlates with their income levels, which surpass those of other agricultural groups.

Independent smallholders include a smaller percentage of university graduates (6.7%) but exhibit the highest proportion of high school graduates at 43.3%, followed by 40% of junior high school graduates and merely 10% of elementary school graduates. In Bojo Village, plasma smallholders have diminished educational attainment, with merely 3.3% holding university degrees, 33.3% having completed high school, 40% possessing junior high school diplomas, and 23.3% achieving elementary school education. Lower educational attainment correlates with various characteristics, including age, reluctance to pursue formal education, and geographical barriers to educational institutions. However, statistical analysis revealed that educational differences among household heads were not statistically significant (χ2 = 6.747, df = 6, p = 0.345), suggesting similar educational foundations across the three groups.

Data indicate major disparities among groups regarding children’s schooling (Table 6). Offspring of ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit the highest educational attainment, with 26.7% holding university degrees, 40% completing high school, and 33.3% finishing junior high school. Independent smallholders exhibit a same trend, albeit with a reduced proportion of university graduates (10%), alongside 50% high school graduates, 33.3% junior high school graduates, and 6.7% elementary school graduates.

The most distinct situation is observed among the offspring of plasma smallholders, with none attaining higher education; 33.3% are high school graduates, 30% are junior high school graduates, 16.7% are elementary school graduates, and 20% are not enrolled in school. Chi-square analysis confirmed that these differences in children’s educational attainment were statistically significant (χ2 = 27.434, df = 8, p = 0.001), indicating distinct educational trajectories emerging among the next generation of smallholder families.

The training component reveals notable disparities across the three cohorts of oil palm growers (Table 7). In Bojo Village, plasma smallholders exhibit the highest training attendance rate, with 100% attending maintenance and fertilization training as well as fire handling training, while 56.7% engaged in further training. The elevated participation indicates a more organized mentoring framework provided by their partner company, PT WKSM.

Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit significant training engagement rates, with 100% attending maintenance and fertilization training, 86.7% engaging in fire management training, and 33.3% partaking in further training. The significant participation is a result of the transmigration program, which was specifically created with an extensive mentorship structure.

Independent smallholders have reduced training participation rates, with merely 56.7% attending maintenance and fertilization training, 6.7% engaging in fire management training, and none partaking in additional training. This limited engagement may stem from their status as independent smallholders, unencumbered by government initiatives or corporate affiliations.

These training programs address multiple technical facets of oil palm farming, encompassing the selection of quality oil palm seedlings, differentiation between ripe and unripe oil palm fruit, appropriate fertilization methods, and the sanitation of plants and planting zones.

Variations in training intensity can eventually influence the quality of plantation management and the productivity of each farming group. These observed differences in training participation patterns reflect the distinct institutional support systems available to each smallholder typology, with plasma smallholders benefiting from corporate-sponsored programs, ex-PIR transmigrants accessing government-facilitated training, and independent smallholders relying primarily on self-directed learning approaches.

3.1.4. Social Capital

The social capital among the three groups of oil palm smallholders in Budong-Budong District exhibits varied patterns (Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10).

Table 8.

Mutual Assistance Between Groups of Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

Table 9.

Membership in Organization of Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

Table 10.

Networking in Business of Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit the highest levels of social capital, especially in collaborative endeavors and mutual assistance (Table 8). Data indicate complete participation in mutual help among groups, with full involvement in community cooperation activities and smallholder group meetings (100%), highlighting the community’s robust tradition of solidarity. Participation rates in religious activity meetings are notably high at 76.7%, whereas engagement in family savings groups or harmony meetings is comparatively lower at 33.3%.

Subsequently, independent smallholders exhibit moderate patterns of social participation in mutual assistance activities. Only 30% participate in community mutual assistance, while 56.7% attend smallholder group meetings. Participation in religious activities stands at 46.7%, indicating significant engagement in communal spiritual dimensions. Their participation in family gatherings or harmony meetings is minimal at just 6.7%.

Plasma smallholders have distinct traits of social engagement. In formal activities, 63.3% participate in smallholder group meetings, although only 33.3% are affiliated with oil palm smallholder associations. They exhibit considerable involvement in family savings groups (36.7%), suggesting robust informal social networks. Nonetheless, engagement in mutual cooperation (16.7%) and religious activities (6.7%) is comparatively minimal. Statistical analysis confirmed that these participation patterns in mutual assistance activities differ significantly across the three smallholder typologies, with all measured social activities showing statistically significant differences: family gatherings (χ2 = 8.527, df = 2, p = 0.014), community mutual assistance (χ2 = 48.113, df = 2, p < 0.001), religious activities (χ2 = 30.136, df = 2, p < 0.001), and smallholder group meetings (χ2 = 16.705, df = 2, p < 0.001).

Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit considerable engagement levels inside formal organizations (Table 9). Approximately 80% are affiliated with oil palm smallholder associations, indicating their recognition of the significance of professional organizations in facilitating their agricultural endeavors. Over fifty percent (53.3%) actively participate as administrators in harmony/religious organizations, underscoring their significant contribution to the community’s social and spiritual fabric. Despite being smaller in number, their engagement in social organization and political party management (16.7%) and village administration (3.3%) indicates participation in local political and governmental matters.

Independent smallholders show strong participation in certain formal organizations, with 86.7% belonging to oil palm smallholder associations, demonstrating their focus on industry-specific networks. However, they have limited engagement in other organizational roles, with only 10% involved in community organizations or political parties, 6.7% serving on boards of harmony/religious organizations, and 6.7% holding village official positions.

Plasma smallholders have more limited organizational participation. Only 33.3% are affiliated with oil palm smallholder associations, significantly lower than the other two groups. Their participation as board members of harmony/religious organizations is also low at 13.3%, and none participate in community organizations or political parties. Their village official participation matches ex-PIR transmigrants at 3.3%. Chi-square analysis revealed significant differences in organizational membership patterns, particularly in oil palm smallholder associations (χ2 = 22.800, df = 2, p < 0.001) and harmony/religious organizations (χ2 = 26.110, df = 2, p < 0.001), while differences in community/political organization participation approached significance (χ2 = 5.213, df = 2, p = 0.074). Village official participation showed no significant differences (χ2 = 0.523, df = 2, p = 0.770) across groups.

The business network of ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders demonstrates effective diversification (Table 10). A majority (63.3%) participate in independent business groups/micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), indicating their inclination to pursue economic activity beyond oil palm cultivation. Nearly half (46.7%) are members or administrators of cooperatives, demonstrating their recognition of the significance of microfinance institutions in facilitating economic operations. Participation in oil palm transportation services (23.3%), however modest, demonstrates their commitment to engaging in the oil palm industry value chain.

Independent smallholders show a focused business networking strategy. They have significant engagement in oil palm transportation services (70%), reflecting their business specialization within the oil palm value chain. However, they show no participation (0%) in cooperatives or independent business groups/MSMEs, suggesting they prioritize direct service provision in the oil palm sector rather than diversified business activities or formal cooperative structures.

Plasma smallholders demonstrate a strong dependence on cooperative structures, with 86.7% serving as members or administrators of cooperatives, underscoring the crucial importance of formal organizations within their plasma system. However, they show no participation (0%) in independent business groups/MSMEs or palm oil transport services, indicating their reliance on structured partnerships rather than independent business ventures. Statistical analysis confirmed highly significant differences in all business networking activities across the three groups: members/board of cooperative membership (χ2 = 45.720, df = 2, p < 0.001), independent business groups/MSMEs (χ2 = 48.169, df = 2, p < 0.001), and palm oil transport services (χ2 = 34.895, df = 2, p < 0.001).

These disparities indicate distinctions in the social framework and adaptive methods of each group. Ex-PIR smallholders, as transmigrant communities, particularly from the Javanese ethnic group, embody robust traditions of mutual collaboration and solidarity. This is essential for establishing and sustaining social networks that enhance their economic and social well-being in the context of transmigration. Independent smallholders prioritize networks directly associated with oil palm productivity and commercialization, evidenced by their significant participation in oil palm smallholder associations and transportation services. Concurrently, plasma smallholders are increasingly aligned with formal entities like cooperatives that link them to partner enterprises.

These varying involvement patterns demonstrate how each group formulates survival strategies via social networks. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders typically preserve conventional social capital while establishing contemporary economic networks. Independent smallholders enhance networks that bolster their autonomy, whereas plasma smallholders depend more on official frameworks that facilitate cooperation with corporations. The statistical significance of these differences across multiple dimensions of social capital confirms that each smallholder typology has developed distinct social strategies that align with their historical origins, institutional arrangements, and livelihood objectives.

3.1.5. Financial Capital

The financial capital of the three types of oil palm smallholders in Budong-Budong District exhibits diversity (Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13).

Table 11.

Monthly Income of Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

Table 12.

Loan Amounts of Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

Table 13.

Savings of Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit the most robust financial status (Table 11), with 66.7% earning between IDR 4–8 million monthly, 20% earning between IDR 8–12 million, and 10% earning beyond IDR 12 million. Merely 3.3% earn between IDR 1–4 million monthly, indicating a significantly high income distribution within this cohort. Independent smallholders exhibit a diminished income distribution, with 50% earning IDR 1–4 million, 33.3% earning IDR 4–8 million, 10% earning IDR 8–12 million, and 6.7% earning in excess of IDR 12 million. Simultaneously, plasma smallholders have the lowest income levels, with the majority (83.3%) earning between IDR 1–4 million and the remainder (16.7%) earning between IDR 4–8 million, with no individuals exceeding an income of IDR 8 million. Statistical analysis confirmed that these income disparities among the three smallholders groups were highly significant (χ2 = 40.068, df = 6, p < 0.001), demonstrating substantial differences in earning capacity across the different smallholder typologies.

Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders have the highest loan levels (Table 12), with 83.3% possessing loans exceeding IDR 20 million, 13.3% holding loans between IDR 10–20 million, and 3.3% maintaining loans ranging from IDR 1–10 million. Independent smallholders exhibit more moderate borrowing behaviors, with 53.3% possessing loans ranging from IDR 10–20 million, 26.7% holding loans between IDR 1–10 million, and 13.3% without any loans. Plasma smallholders possess 50% with debts ranging from IDR 10–20 million, 26.7% with loans between IDR 1–10 million, and 20% without any loans. Chi-square analysis revealed highly significant differences in borrowing patterns (χ2 = 58.465, df = 6, p < 0.001), indicating that each smallholder group has developed distinct debt management strategies aligned with their financial capabilities and institutional access.

Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit the most robust savings profile (Table 13), with 60% possessing savings over IDR 20 million, 23.3% holding savings between IDR 10–20 million, and 16.7% maintaining savings of IDR 1–10 million. Independent smallholders possess savings as follows: 40% have between IDR 10–20 million, 33.3% have above IDR 20 million, and 26.7% have between IDR 1–10 million. Currently, the predominant proportion of plasma smallholders (53.3%) possess no savings, 40% have savings ranging from IDR 1–10 million, and merely 6.7% have savings between IDR 10–20 million. Statistical testing confirmed highly significant differences in savings accumulation patterns across the three groups (χ2 = 59.531, df = 6, p < 0.001), reflecting the varying financial security levels and wealth accumulation capabilities among different smallholder typologies.

This financial capital pattern illustrates how disparities in resource access and financial management practices influence the economic well-being of each group. The substantial debts incurred by ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders are offset by significant income and savings, demonstrating their capacity to handle productive debt well. Conversely, the minimal savings of plasma smallholders indicate their constraints in asset accumulation despite their comparatively high loan levels. The statistical significance across all three financial indicators—income, loans, and savings—confirms that these groups operate within fundamentally different financial ecosystems, with ex-PIR transmigrants demonstrating the highest financial capacity, independent smallholders showing moderate financial resilience, and plasma smallholders facing the greatest financial constraints despite institutional support structures.

3.2. Adaptive Strategies and Economic Behavior of Smallholders

The livelihood strategies of the three categories of oil palm smallholders in Budong-Budong District exhibit variations, especially with early planting approaches and methods for addressing price volatility. In the villages of Salugatta, Tinali, and Pontanakayyang, ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders first collaborated with the state-owned enterprise Nusantara Plantation Limited Company-19 (NPLC19), concentrating on rubber cultivation in business land 2. In 1994, a partnership transfer occurred between PT Surya Raya Lestari II and PT Bhadra Sukses, both subsidiaries of PT Astra Agro Lestari, due to poor results. This move signified a shift in commodities from rubber to oil palm, with all planting and maintenance expenses incurred by the corporations.

Following the expiration of the plants’ productive lifespan of 20 years, a replanting initiative was executed in 2019 for 200 hectares throughout these three communities, funded by the Oil Palm Plantation Fund Management Agency (OPPFMA) program.

Data indicate (Table 14) that 73.3% of ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders obtained this replanting subsidy. Nevertheless, not all smallholders were able to participate in this program due to several obstacles, including challenges in organizing smallholder groups, frequent instances of land transfers, and intricate bureaucratic procedures involving multiple stakeholders.

Table 14.

Initial Planting Livelihood Strategies of Oil Palm Smallholders (source: field interview results).

Smallholders without access to replanting funding devised other solutions, with 16.7% borrowing capital from intermediaries, 6.7% obtaining People’s Business Credit (PBC), and 3.3% leveraging social capital. In contrast, independent smallholders exhibited varied patterns, with 73.3% opting to collaborate with oil palm firms, while the remaining smallholders were divided among PBC (10%), intermediary loans (10%), and social capital (6.7%). Plasma smallholders exhibited the most consistent pattern, with 100% depending on collaboration with PT WKSM. Statistical analysis confirmed highly significant differences in initial planting strategies across the three smallholder groups (χ2 = 81.396, df = 8, p < 0.001), demonstrating that each group’s access to and preference for different financing mechanisms reflects their distinct institutional relationships and historical development pathways.

The discrepancies in initial financing strategies illustrate the intricate history of oil palm plantation development in the region and demonstrate the impact of government regulations, market dynamics, and the influence of large corporations on smallholders’ livelihood strategy decisions. The disparities in access to financial sources ultimately lead to variations in the development and viability of oil palm plantation enterprises among different smallholder groups.

In the face of price drops, the three groups exhibit distinct adaptation techniques (Table 15). Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders employ substantial measures for reducing production inputs in oil palm cultivation, with 73.3% opting against fertilization, 66.7% ceasing cleaning and pruning procedures, and 70% allowing oil palm fruits to remain unharvested. Only 26.7% decrease fertilizer use, while 30% persist in harvesting despite incurring losses.

Table 15.

Smallholders Cultivation Management Strategies in Response to Palm Oil Price Decline (source: field interview results).

Concurrently, plasma smallholders exhibit distinct patterns owing to their affiliations with partner companies. Despite a 90% reduction in fertilizer application, basic maintenance is necessary. Approximately 53.3% engage in minor cleaning, whereas 50% persist in harvesting despite incurring losses. Regarding labor, 80% depend on corporate workforce.

Independent smallholders exhibit analogous trends, albeit with more intensity in the decrease of production inputs. Approximately 86.7% refrain from fertilization (Table 16), 86.7% cease cleaning, and 93.3% do not harvest oil palm fruit. Only 13.3% decrease fertilizer use, while 6.7% persist in harvesting. Furthermore, 70% utilize their own or family labor, while 26.7% employ hired labor. Chi-square analysis revealed highly significant differences in labor utilization strategies (χ2 = 45.464, df = 4, p < 0.001), indicating that each smallholder group has developed distinct approaches to managing labor costs during economic downturns, with plasma smallholders uniquely benefiting from corporate labor support while ex-PIR transmigrants and independent smallholders rely predominantly on family-based labor strategies.

Table 16.

Labor Utilization Strategies by Palm Oil Smallholders in Response to Price Decline Declines (source: field interview results).

Each group demonstrates distinct techniques for financing daily living expenses (Table 17). Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders predominantly depend on savings (66.7%) as their primary source of finance. Other minor sources include farming and livestock (13.3%), assistance from family groups (6.7%), family members (3.3%), neighbors (3.3%), working as farm laborers (3.3%), and borrowing from traders (3.3%).

Table 17.

Management of Oil Palm Plants by Smallholders During Price Declines (source: field interview results).

Independent smallholders frequently engage in business diversification, with 66.7% opting for gardening, livestock farming, aquaculture, or managing micro-enterprises. Simultaneously, plasma smallholders frequently engage as agricultural laborers (26.7%) and perform business diversification (30%) to fulfill their daily requirements. Statistical testing confirmed highly significant differences in livelihood diversification strategies (χ2 = 60.602, df = 14, p < 0.001), demonstrating that each group has developed fundamentally different approaches to income generation during economic stress, with ex-PIR transmigrants relying on accumulated savings, independent smallholders emphasizing diversification, and plasma smallholders combining wage labor with modest diversification efforts.

The disparities in adaption tactics indicate variances in economic resilience and flexibility among each group when confronted with economic pressures. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders with substantial funds possess superior financial resilience, whereas independent smallholders depend on their capacity for business diversification, and plasma smallholders are more constrained by partnership models that restrict their adaptability.

As oil palm prices increase, techniques for allocating the supplementary money also differ (Table 18). Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit a pronounced inclination towards saving, with 53.3% opting to reserve their supplementary income. Furthermore, 20% allocate their income for home renovations, 16.7% for purchasing or servicing automobile loans, 6.7% for acquiring new oil palm land, and 3.3% for debt repayment. This trend demonstrates their long-term focus in financial management.

Table 18.

Oil Palm Smallholders’ Strategies During Price Increases (source: field interview results).

Independent smallholders exhibit varied priorities, with 40% allocating supplementary income towards home renovations, 30% towards debt repayment, 13.3% towards savings, 10.3% towards vehicle purchases or installment payments, and 3.3% towards acquiring oil palm property. The emphasis on home enhancement and debt settlement indicates their commitment to enhancing quality of life and alleviating financial strain.

Concurrently, plasma smallholders exhibit patterns akin to those of independent smallholders, albeit with varying percentages. Approximately 36.7% allocate supplementary income for home renovations, 26.7% for debt repayment, 26.7% for automobile purchases or installment payments, and 10% for savings. No plasma smallholders invest extra revenue in acquiring new oil palm land, perhaps due to financial constraints and their affiliations with current partnership agreements. Chi-square analysis revealed significant differences in income allocation strategies during price increases (χ2 = 25.653, df = 8, p = 0.001), confirming that each group’s spending priorities reflect their distinct economic positions and long-term development strategies.

These strategic disparities indicate variances in the economic and social priorities of each group. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders with enhanced economic capacity typically focus on asset accumulation and investing. Independent and plasma smallholders prioritize meeting fundamental infrastructure requirements and alleviating debt, highlighting disparities in welfare and economic capacity among the three smallholder categories.

The strategic disparities illustrate differences in resource accessibility, institutional affiliations, and risk management inclinations among the groups. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders with greater capital typically adopt long-term investment strategies, whereas independent smallholders exhibit greater flexibility in business diversification, and plasma smallholders are more constrained by partnership models with corporations. The statistical significance across all measured livelihood strategy dimensions—initial planting financing, cultivation management, labor utilization, daily expense management, and income allocation during price increases—confirms that these three smallholder typologies operate within fundamentally different livelihood systems. Each group has developed adaptive strategies that reflect their institutional embeddedness, with ex-PIR transmigrants demonstrating financial resilience and long-term planning, independent smallholders showing entrepreneurial flexibility and diversification capacity, and plasma smallholders exhibiting institutional dependence balanced with creative survival mechanisms.

3.3. Economic Outcomes and Welfare of Smallholder Households

The livelihood outcomes of the three groups of oil palm smallholders in Budong-Budong District exhibit considerable disparities across different income sources. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit a rather high and equitable income distribution, averaging IDR 186,200,000/month (Table 19). Fifty percent of the total ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders earn an income ranging from IDR 4 to 8 million per month, indicating a solid middle-income status. Additionally, certain groups achieve elevated incomes, with 16.7% of smallholders earning IDR 8–12 million/month and 3.3% exceeding an income of IDR 12 million per month. A mere 3.3% obtain between IDR 1–4 million/month.

Table 19.

Average Income of Oil Palm Smallholders in Budong-Budong District (source: field interview results).

This benefit is bolstered by substantial land ownership, with 50% possessing 1–2 hectares of oil palm land and some exceeding 4 hectares. Furthermore, they possess greater knowledge in administering oil palm estates due to their involvement in the transmigration program. They also implement land management efficiency by converting all land, including yards, into oil palm plantations.

This elevated income distribution is also evident in their capacity to save, as 60% of ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders own savings above IDR 20 million. This indicates that their wage level is adequate not only to satisfy daily necessities but also to facilitate the accumulation of financial assets. This income pattern indicates a superior level of welfare relative to other smallholder groups, as evidenced by their capacity to possess permanent housing (60%) and ownership of motorbikes and automobiles (73.3%).

Independent smallholders exhibit more varied income patterns across oil palm and non-oil palm yields, averaging IDR 141,264,000/month (Table 19). In the oil palm plantation industry, 36.7% of independent smallholders generate a monthly income of IDR 1–4 million, indicating that the majority belong to lower-middle income brackets within this sector. Simultaneously, 6.7% obtain an income of IDR 4–8 million and IDR 8–12 million, signifying that a limited fraction attains upper-middle income levels from oil palm.

This pattern illustrates the distinct traits of independent smallholders that cultivate non-oil palm land for diverse commodities. With an average non-oil palm land ownership of 1–2 hectares, they effectively generate substantial supplementary revenue sources. This technique enhances economic resilience amid fluctuations in oil palm prices and enables the optimization of land for diverse economically valuable crops. The significant income variation among independent smallholders reflects their adaptive capacity to diversify income sources, positioning them in an intermediate economic status between the capital-rich ex-PIR transmigrants and the institutionally constrained plasma smallholders.

Plasma smallholders earn less from the oil palm sector than the other two smallholder types, averaging IDR 11,840,000 month. Approximately 40% of plasma smallholders generate a monthly revenue of IDR 1–4 million from oil palm production, while hardly 3.3% attain an income of IDR 4–8 million. No plasma smallholders receive oil palm income greater than IDR 8 million monthly. The diminished income from oil palm is associated with a restricted land area, which spans only 0.5 to 2 hectares in collaboration with PT. WKSM.

Notably, their income diversification technique via non-oil palm plantations (Table 20) indicates that 23.3% of independent smallholders may produce supplementary income ranging from IDR 1 to 4 million from products including corn, bananas, coconuts, and cocoa. Furthermore, 6.7% of smallholders achieve an additional IDR 4–8 million, while 3.3% attain an additional IDR 8–12 million from the non-oil palm industry. This diversification method seems to be their adaptability as indigenous inhabitants who recognize the significance of not depending just on a single commodity.

Table 20.

Average Income from Non-Oil Palm Plantation and Non-Agricultural Sources (source: field interview results).

To offset the diminished revenue from oil palm, plasma smallholders cultivate alternative income sources from non-oil palm plants. Up to 33.3% of them earn an income of IDR 4–8 million from this industry, while 13.3% attain an income of IDR 8–12 million. Diversifying into non-oil palm crops like corn, bananas, and oranges enhances overall household income. Notably, revenue from the non-oil palm sector surpasses that from oil palm, indicating the effectiveness of their crop diversification policy, as illustrated in Table 10.

Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders exhibit superior diversification in income from alternative sources, including entrepreneurship and micro-businesses. Approximately 6.7% earn IDR 1–4 million, 10% earn IDR 4–8 million, 6.7% earn IDR 8–12 million, and 3.3% earn in excess of IDR 12 million from this industry. Independent smallholders generate only 16.7% of their income from entrepreneurship or micro-businesses, while a mere 3.3% of mainstream smallholders derive revenue from this industry.

Nonetheless, regarding revenue from alternative sources like entrepreneurship or micro-businesses, the involvement of plasma smallholders is markedly restricted, indicating their constraints in accessing or establishing enterprises beyond agriculture. This pattern suggests a substantial reliance on the agriculture industry, encompassing both oil palm and non-oil palm, as the primary source of income for most smallholders’ households.

The comprehensive analysis of livelihood assets, strategies, and outcomes reveals that the three oil palm smallholder typologies in Budong-Budong District operate within fundamentally different socio-economic systems. This confirms that these groups have developed distinct livelihood trajectories shaped by their historical origins, institutional frameworks, and resource access patterns.

These systematic differences extend beyond individual farmer capabilities to reflect the underlying institutional architectures that shape smallholder development pathways. Ex-PIR transmigrants benefit from government-facilitated infrastructure, standardized land allocation, and historical access to technical support, enabling capital accumulation and risk management through savings. Independent smallholders leverage indigenous knowledge systems and flexible land use strategies to maintain economic autonomy while pursuing diversified income streams. Plasma smallholders operate within corporate-mediated frameworks that provide technical support and market access but constrain land ownership and limit autonomous decision-making capacity.

The statistical significance of these differences across assets, strategies, and outcomes confirms that sustainable oil palm smallholder development requires typology-specific interventions rather than universal approaches. Policy frameworks must recognize that each group’s livelihood system reflects distinct adaptive strategies developed in response to different historical, institutional, and environmental contexts. The economic prosperity of smallholder households depends not solely on individual agricultural productivity but fundamentally on the institutional arrangements and resource access patterns that enable or constrain their capacity to build resilient, diversified livelihood systems within their specific socio-economic contexts.

4. Discussion

4.1. Livelihood Capital

Differences in ownership and access to livelihood capital among the three groups of oil palm smallholders demonstrate distinct patterns based on historical and structural contexts. Disparities in natural and physical capital ownership among oil palm smallholder typologies are rooted in historical agrarian policies and structural developments. Through the sustainable livelihoods framework developed by Scoones [18,28], we can understand how the PIR transmigration program in the 1980s provided initial advantages to ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders through wider land allocation (averaging 3 hectares per household) and technical support from nucleus companies, creating what is referred to as path dependency in oil palm development [6,29]. Recent studies confirm that historical differences in land acquisition models continue to influence smallholder welfare trajectories to the present day [6,18,28,30]

Scoones [18,28] emphasized that sustainable livelihoods must be able to cope with and recover from stresses and shocks, maintain or enhance capabilities and assets, and provide sustainable livelihood opportunities for the next generation. This is reflected in the different land ownership patterns among the three groups. In line with Scoones, Chambers and Conway [16,18,28] defined livelihood as a combination of capabilities, assets, and activities required for means of living—a concept that helps explain why initial differences in land ownership create long-term effects on livelihood trajectories. This indicates that these initial conditions create path-dependent trajectories that are difficult to change even with progressive policy interventions [11,31,32,33].

Independent smallholders, who are predominantly indigenous residents, experience different processes in acquiring land through claims on public land, implementing what Chambers and Conway [16] identified as diversification strategies by cultivating non-oil palm crops such as corn, bananas, coconut, and cocoa. Scoones [18] categorized this strategy as a form of resilient livelihoods that reduces vulnerability to single commodity market fluctuations. Meanwhile, plasma smallholders, who are newcomers, are compelled to accept restrictive partnership terms with PT WKSM, creating what Chambers and Conway [16] described as structural dependency, which limits their autonomy and adaptive capacity. Contemporary partnership models often generate new structural dependencies that reinforce power inequalities in the oil palm value chain [9,12,30,31,32,33].

These divergent historical pathways have created structural stratification in productive asset ownership that directly impacts the capacity for physical capital accumulation [31,34]. Within Scoones’ [18] framework, the higher vehicle ownership among ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders represents an example of productive bricolage—the ability to combine various productive assets to create broader livelihood opportunities. This confirms that initial differences in productive asset ownership influence households’ ability to accumulate additional capital, creating what is termed as cumulative advantage in social stratification theory [6,35,36].

Housing conditions of better quality reflect what Chambers and Conway [16] referred to as productive assets, namely resources that can help households improve their welfare. Conversely, the prevalence of non-permanent houses among plasma smallholders and limited vehicle ownership indicates serious asset constraints. This situation creates what is known as an asset-based poverty trap, a condition where households lack sufficient basic assets needed to escape poverty and improve their standard of living [18,37]. In other words, due to minimal assets—such as adequate housing, vehicles, or business capital—these households are trapped in stagnant economic conditions and unable to reach the starting point needed to begin upward economic mobility [18,37,38].

The role of institutions, particularly government and partner companies, not only shapes opportunities for access to livelihood capital but also creates structures of long-term dependency for farmers. The PIR transmigration program, although successful in improving the welfare of ex-transmigrants initially, indirectly limited their economic flexibility by encouraging single specialization in oil palm commodities. This has made ex-PIR smallholders more vulnerable to global price fluctuations. Meanwhile, the plasma partnership scheme exhibits a pattern of captive value chain, where partner companies control access to inputs, outputs, and prices, thus reducing plasma smallholders autonomy in determining adaptation strategies. This inequality reinforces dependency traps that hinder livelihood diversification and weaken farmers’ long-term adaptive capacity. Therefore, institutional interventions that are more transformative and strengthen farmer autonomy are needed to improve the sustainability of livelihood systems in this region.

Socio-cultural factors play a crucial role in shaping differences in social and human capital. The strong social capital of ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders, evidenced by their full participation in communal work (gotong royong) and farmer groups, is inseparable from their Javanese cultural background that emphasizes collectivism. In Scoones’ [18] typology, this represents an example of bonding social capital that can facilitate collective action and risk sharing. Previous studies have also demonstrated that ethnicity-based social networks remain important determinants in accessing resources and information in oil palm plantation areas [39,40].

Meanwhile, plasma smallholders with Mandar ethnic backgrounds and their Siwalli Parri tradition demonstrate different patterns of social participation, which according to Chambers and Conway [16] can function as social safety nets in different contexts. Woolcock and Narayan [41] explained that variations in the type and intensity of social capital influence access to information, resources, and negotiating power within formal institutions—an analysis that reinforces Scoones’ [18,28] framework regarding the importance of social capital in shaping collective capabilities. This confirms that social capital remains a key mediating variable that determines the ability of farmer households to access economic opportunities and navigate relationships with institutional actors [15,42,43].

Differences in human capital, such as ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders having university education compared to plasma smallholders, reflect what Chambers and Conway [16] identified as capability inequalities that affect households’ ability to access better livelihood opportunities. However, plasma smallholders demonstrate the highest participation in technical training for maintenance and fire management, indicating what Nonaka and Takeuchi [44] described as structured tacit knowledge transfer. Scoones [18] emphasized that both formal knowledge and tacit knowledge play important roles in shaping adaptive capability—the ability to respond to changes and uncertainties in livelihood contexts [18,44]. This indicates that technical training programs do improve productivity, but without enhancement of managerial capacity and market access, plasma smallholders remain vulnerable to structural dependency on partner companies [6,45,46].

Significant differences in financial capital reflect power relationship dynamics in the oil palm value chain. The higher savings capacity of ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders compared to plasma smallholders without savings reflects what Bowles et al. [47] identified as persistent inequality. Within Scoones’ [18] framework, this phenomenon exemplifies traps and thresholds—dynamics that create different patterns of asset accumulation among different livelihood groups. He emphasized that the ability to save and invest is an important component of livelihood security—the capacity to face shocks and stress without sacrificing long-term livelihoods [18,28]. Disparities in saving ability widen over time, confirming the existence of diverging trajectories in wealth accumulation among different oil palm farmer typologies [38,48].

This inequality is reinforced by unequal access to formal credit and market opportunities, with ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders having more diverse business networks, while plasma smallholders are limited to cooperative membership. This demonstrates that different models of integration into value chains create patterns of asymmetric dependency—ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders have greater autonomy in production and marketing decisions, while plasma smallholders are trapped in captive value chain relationships [11,49]. Recent studies have confirmed the persistence of captive governance structures in relationships between plasma smallholders and nucleus companies, which limit farmers’ ability to accumulate economic surplus and transform their position within the value chain [50,51,52].

Within Scoones’ [18] framework, these differences illustrate how varying combinations of capabilities, assets, and activities create different livelihood pathways—trajectories shaped by complex interactions between historical, institutional, and socio-ecological contexts. Chambers and Conway [16] emphasized that sustainable livelihoods depend not only on asset accumulation but also on capabilities to adapt, transform, and reproduce these assets in continuously changing contexts.

This comparative analysis thus demonstrates how PIR transmigration programs and plasma partnership models have created a structuration of livelihoods—patterns that are simultaneously shaped by and shape the broader socio-economic structures in the oil palm plantation areas of Central Mamuju.

4.2. Livelihood Strategy

The different livelihood strategies exhibited by the three groups of oil palm smallholders in Central Mamuju have demonstrated forms of interaction between resource access, capabilities, and institutional contexts. In the initial planting phase, ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders showed advantages in accessing OPPFMA funds, reflecting what Chambers and Conway [16] described as institutional capability—the ability to navigate formal systems and utilize government programs. When facing price declines, the consolidation strategy of ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders through the use of savings and input reduction aligns with Scoones’ [18] thinking that resource consolidation aims to maintain the asset base during crises. However, Bebbington [53] cautioned that prolonged use of liquid assets without adequate diversification can create a vulnerability trap—a condition where short-term resilience is achieved at the expense of long-term sustainability [53,54,55]. Previous studies have documented that farmers with larger savings are indeed more resilient in facing short-term price shocks but remain vulnerable to prolonged crises without adequate diversification strategies [17,56,57,58].

Independent smallholders demonstrate what Scoones [18] categorized as adaptive diversification by shifting to non-oil palm enterprises when prices decline [18,59]. Such diversification can function as a buffer against shocks and create more resilient livelihood pathways [17,34]. However, without productive investment support in non-agricultural activities, this diversification remains defensive in nature [18,55,59,60,61]. Meanwhile, plasma smallholders with high dependency on corporate partnerships and limited coping strategies (working as farm laborers) exhibit what Chambers and Conway [16] identified as dependent security—a livelihood model that sacrifices adaptive autonomy for short-term security. This phenomenon was further explained by McCarthy [9] in his study of oil palm partnership schemes in Indonesia and Li [11] critiquing the power relationship inequalities in plantation expansion.

The responses to increased oil palm prices further clarify differences in long-term strategies. The accumulation strategy of ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders through savings and vehicle investment reflects what Scoones [18] referred to as productive reinvestment—a strategy that strengthens the asset base for future livelihoods. In contrast, the focus of independent smallholders and plasma smallholders on house renovation demonstrates what Chambers and Conway [16] identified as consumptive investment—improving quality of life without significantly strengthening productive capacity. This pattern, especially for plasma smallholders, may reinforce choices that prioritize short-term security at the expense of long-term adaptive flexibility [59,62,63,64].

This livelihood analysis confirms the arguments of Scoones [18] and Chambers and Conway [16] that livelihood sustainability depends not only on asset accumulation but also on the development of adaptive and transformative capabilities. The three farmer groups demonstrate path-dependent adaptations—adaptive strategies constrained by historical decisions and structural positions within the political ecology of oil palm plantations. As emphasized by Chambers and Conway [16], truly sustainable livelihoods require a balance between short-term resilience and long-term transformation—a balance that appears not yet fully achieved by the three farmer groups in Central Mamuju. These adaptation patterns necessitate policy interventions that focus not only on income stabilization but also on developing adaptive capabilities and transformative diversification appropriate to the specific context of each farmer group.

4.3. Livelihood Outcomes

Livelihood outcomes of the three oil palm smallholder typologies in Central Mamuju reflect differentiated livelihood outcomes formed through complex interactions between asset access, capabilities, and opportunity structures. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders with higher incomes illustrate sustainable livelihood—a condition where households are able to maintain or improve living standards without compromising their resource base [16]. This advantage can be termed a virtuous cycle of accumulation where larger land ownership facilitates economies of scale in oil palm cultivation [18,59], while experiential capital—long experience in oil palm cultivation—enhances production efficiency. Investment in children’s education reflects intergenerational sustainability—the capacity to transmit welfare and capabilities across generations. However, dependence on oil palm monoculture creates specialized vulnerability—vulnerability to single commodity shocks that may threaten long-term resilience [59,65,66].

Independent smallholders with more diverse income patterns demonstrate adaptive diversification—an adaptive response to market and ecological uncertainties [18]. Chambers and Conway [16] underscored that such diversification provides buffers against shocks and creates greater resilience to external disturbances. The strategic choice to maintain non-oil palm crops reflects a risk-hedging livelihood portfolio—a strategy that prioritizes security above profit maximization [18]. The use of additional income for house renovation among independent smallholders indicates a dimension of social sustainability—the capacity to maintain and enhance assets that contribute to social status and inclusivity [53].

Plasma smallholders with limited income from oil palm illustrate constrained livelihoods—livelihoods restricted by structural inequalities in access to resources and markets [18]. Chambers and Conway [16] explained that such inequalities create a vulnerability context that limits adaptive capacity. The asymmetrical plasma partnership model creates adverse incorporation—integration into markets on unfavorable terms [9]. However, the ability of 33.3% of plasma smallholders to generate income of IDR 4–8 million from non-oil palm sectors demonstrates capabilities in action—the capacity to develop alternative strategies amid structural constraints. The absence of higher education among plasma smallholders children illustrates what Scoones [18] described as an intergenerational capability trap—systemic barriers in capability development that persist across generations.

Variation in these non-monetary dimensions of well-being affirms the arguments of Scoones [18] and Chambers and Conway [16] that livelihood outcomes must be understood beyond income indicators, encompassing aspects of social justice, ecological sustainability, and capability development. As emphasized by Chambers and Conway [16], truly sustainable livelihoods require a balance between improving the living standards of the current generation and maintaining the capabilities of future generations—a balance not yet fully achieved by the three farmer groups in Central Mamuju. These findings underscore the need for policy approaches that are context-specific and differentiated in order to address structural barriers and strengthen pathways toward more sustainable and equitable livelihood outcomes.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the purposive sampling approach limits the statistical generalizability of findings beyond the studied communities in the Central Mamuju Regency. Second, reliance on self-reported data may introduce recall bias, particularly regarding income and asset information. Third, ex-ternal factors such as macro-economic policies, climate change impacts, and global market dynamics were not systematically analyzed, which may influence livelihood outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This research reveals significant differences in livelihood assets, strategies, and outcomes among ex-PIR transmigrant, independent, and plasma oil palm smallholders in the Central Mamuju Regency, based on purposive sampling within the research area. Ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders demonstrate stronger physical, financial, and social capital, achieving higher income and welfare indicators. Independent smallholders, though possessing intermediate resources, benefit from diversified income strategies that enhance their resilience. Plasma smallholders face the greatest structural limitations in terms of assets and autonomy, resulting in lower incomes and higher vulnerability. Given the non-probabilistic sampling design, these findings should be interpreted as illustrative of livelihood dynamics in the studied communities, without claims of statistical generalization to broader populations. The results emphasize heterogeneity among smallholder groups and stress the need for more differentiated development approaches.

Policy interventions must recognize the institutionally embedded nature of these livelihood differences and develop typology-specific approaches. For ex-PIR transmigrant smallholders, policies should focus on supporting livelihood diversification beyond oil palm to reduce dependency risks while leveraging their existing financial capital for sustainable investments. Independent smallholders would benefit from improved access to financial services and technical assistance to expand and enhance their diversified agricultural enterprises, building on their demonstrated capacity for crop diversification. Plasma smallholders urgently need empowerment strategies that increase their autonomy, including renegotiation of partnership terms, land tenure security, access to independent markets, and capacity development programs that address their limited land ownership and financial constraints. Concrete actions could include facilitating access to affordable replanting funds across all smallholder groups; developing targeted capacity-building programs focusing on business skills, digital technology use, and cooperative management; promoting inclusive cooperative models that increase bargaining power for plasma smallholders; and strengthening social safety nets and risk management tools for vulnerable groups.

Future research should expand geographical coverage to verify observed patterns across various oil palm landscapes. Furthermore, exploring the role of technology adoption, gender dynamics, and intergenerational knowledge transfer would provide richer insights into factors shaping smallholder resilience. Investigating the implications of climate change on livelihood strategies also remains essential for supporting long-term sustainability in the palm oil sector.

This research contributes by providing empirical evidence with statistical validation of how differences in access to livelihood capital and institutional arrangements shape diverse pathways of resilience or vulnerability among smallholder groups. The demonstrated statistical significance across multiple livelihood dimensions (assets, strategies, and outcomes) establishes a robust empirical foundation for understanding smallholder heterogeneity, providing important lessons for designing more inclusive and sustainable smallholder development policies that recognize the institutionally differentiated nature of smallholder livelihood systems.

Author Contributions

K.A. formulated the research concept, executed field data collecting and analysis, and composed the manuscript draft; H.N. offered methodological guidance, performed research assessment, and facilitated data analysis; D.S. contributed to the formulation of the theoretical framework, offered significant insights for the analysis of livelihood systems, and performed a thorough review of the manuscript’s scientific substance; A.N.T. contributed to the research concept formulation, interpreted research results, and aided in study evaluation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement