Population Aging and Economic Competitiveness in Polish Small Towns

Abstract

1. Introduction

- −

- Constructing a synthetic measure for the progression of aging processes among inhabitants of small towns;

- −

- Identifying types of relationships between the level of economic competitiveness and the measure of population aging for inhabitants of small towns.

2. Population Aging and the Economic Dimension of Competitiveness

3. Materials and Methods

- For economic competitiveness of small towns, the formula is as follows:

- For the measure of population aging in small towns, the formula is as follows:

4. Results

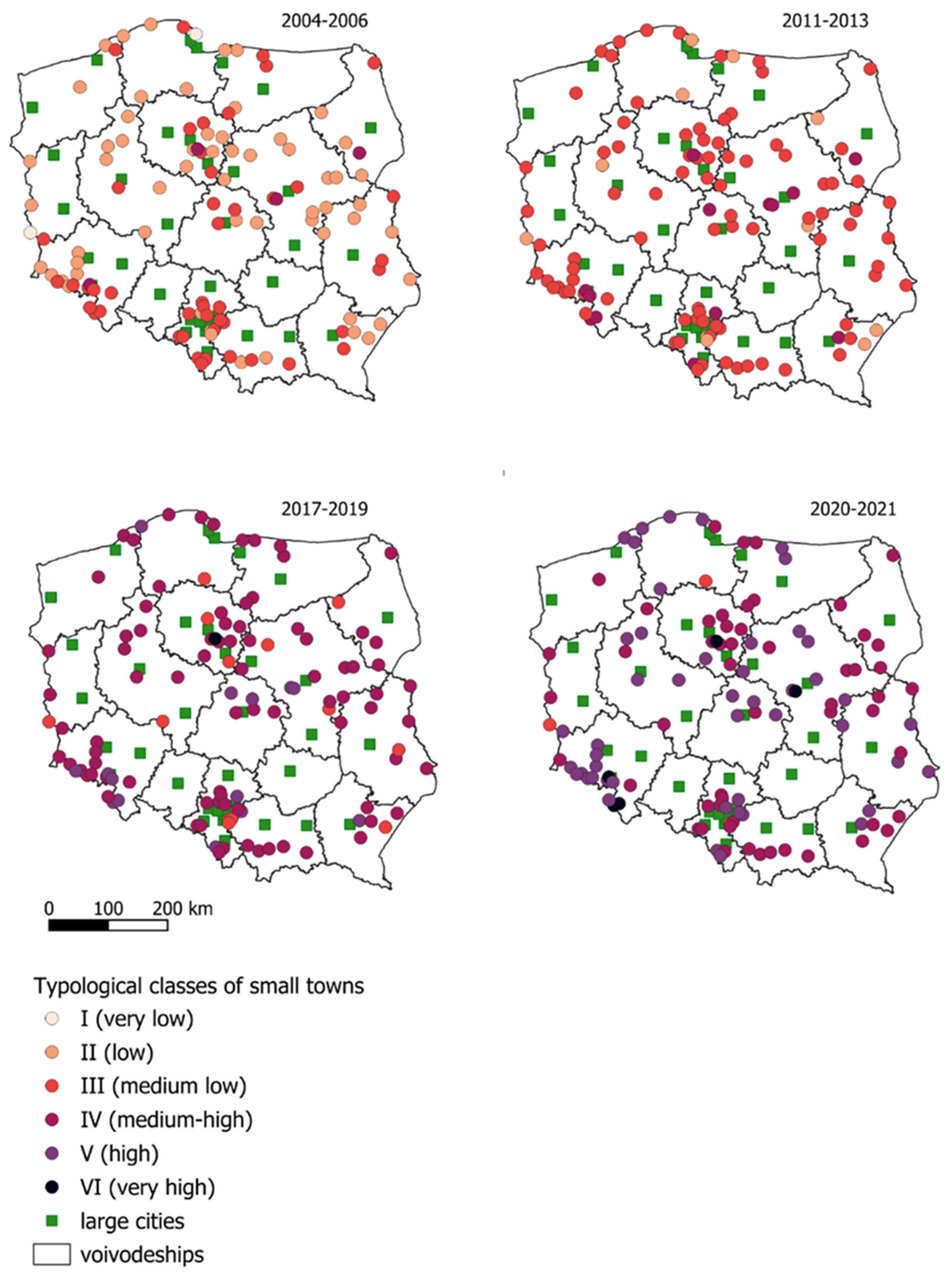

4.1. Measure of Population Aging in Polish Small Towns

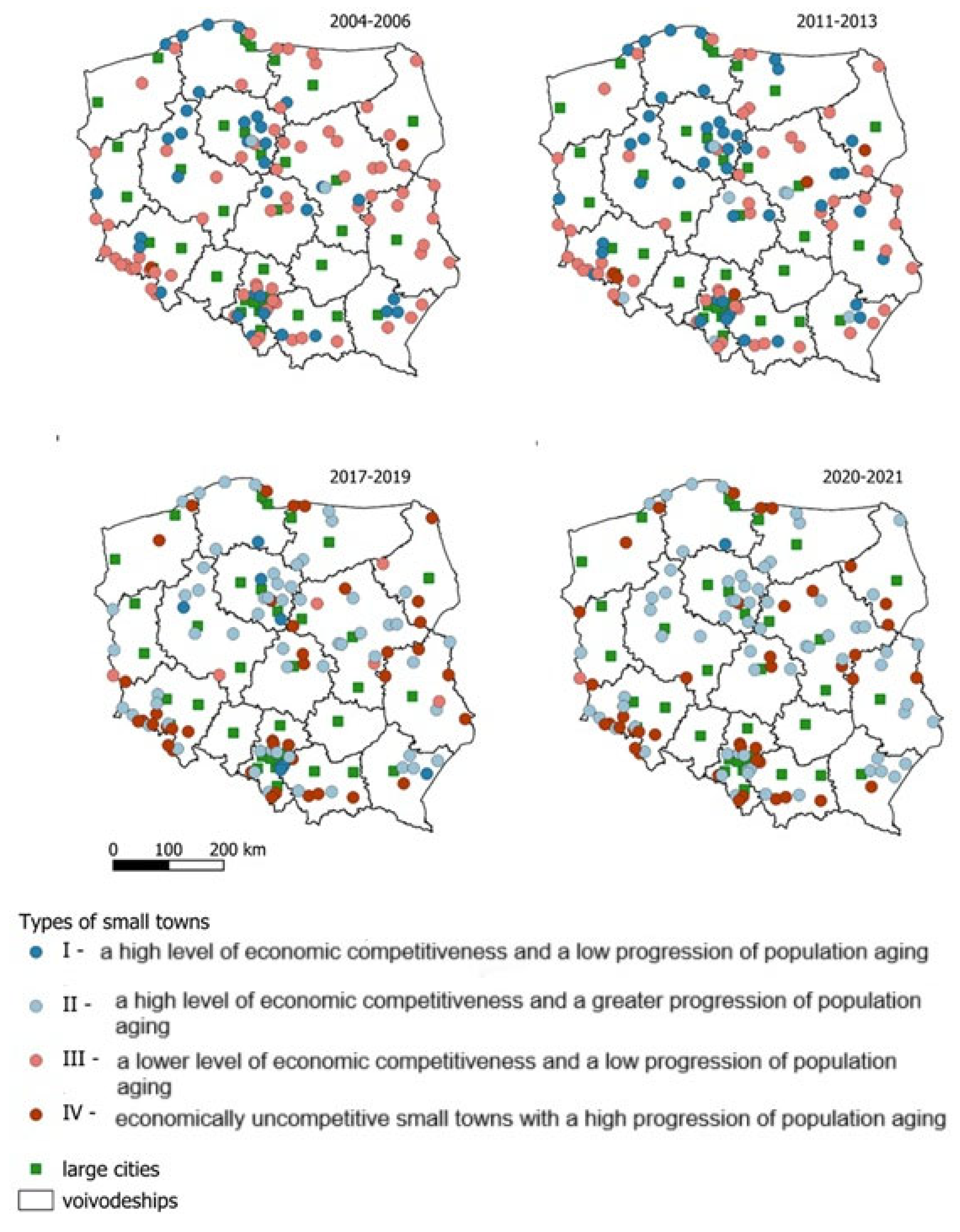

4.2. Population Aging of Small Towns and the Level of Economic Competitiveness

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richert-Kaźmierska, A. Polityka Państwa Wobec Starzenia się Ludności w Polsce; Wydawnictwo CeDeWu: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, S. Population ageing research from a geographical perspective-methodological approach. Bull. Geography. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2007, 8, 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wasilewska, E.; Pietrych, Ł. Starzenie się społeczeństwa a wzrost gospodarczy w krajach Unii Europejskiej. Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2018, 18, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M. Skutki społeczno-ekonomiczne starzenia się społeczeństwa. Wybrane Aspekty Eur. Reg. 2015, 13, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, Z.; Rachwał, T. Starzenie się ludności w dużych miastach Polski na tle pozostałych ośrodków i obszarów wiejskich. Pr. Geogr. 2000, 209, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bank Danych Lokalnych, Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/start (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Janiszewska, A. Starzenie się ludności w polskich miastach. Space–Society–Economy 2019, 29, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafranek-Stefaniuk, E. Procesy demograficzne w miejskich obszarach funkcjonalnych w Polsce. Czas. Geogr. 2024, 95, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, B.; Kwiatek-Sołtys, A.; Kurek, S. Does the process of shrinking concern also small towns? Lessons from Poland. Quaest. Geogr. 2019, 38, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójtowicz, M.; Kurek, S.; Gałka, J. Proces starzenia się ludności miejskich obszarów funkcjonalnych (MOF) w Polsce w latach 1990–2016. Stud. Miej. 2020, 33, 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, A. Procesy starzenia się w środowisku wielkomiejskim w Polsce na początku XXI wieku. Wymiar demograficzny i społeczny. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. W Krakowie 2017, 3, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józefowicz, K. Differences in Economic Competitiveness between Small Towns in Poland. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2024, XXVIΙ, 142–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestas, N.; Mullen, K.J.; Powell, D. The Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth, the Labor Force, and Productivity. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2023, 15, 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Chen, Y.; Xu, S.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. The Role of Population Aging in High-Quality Economic Development: Mediating Role of Technological Innovation. Sage Open 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Mazlan, N.S.; Mohamed, A.B.; Mhd Bani, N.Y.B.; Liang, B. Regional impact of aging population on economic development in China: Evidence from panel threshold regression (PTR). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temsumrit, N. Can aging population affect economic growth through the channel of government spending? Heliyon 2023, 9, e19521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh Trong, N.; Thi Dong, N.; Thi Ly, P. Population aging and economic growth: Evidence from ASEAN countries. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, V. Ageing Population and Economic Growth in Developing Countries A Quantile Regression Approach; Emerging Markets Finance and Trade: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D.; Canning, D.; Fink, G. Implications of population aging for economic growth. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2010, 26, 583–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.L.; Yip, T.M. The role of older workers in population aging–economic growth nexus: Evidence from developing countries. Econ. Change Restruct. 2022, 55, 1875–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buresch, J.M.; Medgyesi, D.; Porter, J.R.; Hirsch, Z.M. Understanding how population change is associated with community sociodemographics and economic outcomes across the United States. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2024, 6, 1465218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, L. The nonlinear effects of population aging, industrial structure, and urbanization on carbon emissions: A panel threshold regression analysis of 137 countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, C.; Liu, C.; Teng, X.; Lv, R.; Cai, Y. The Bilateral Effects of Population Aging on Regional Carbon Emissions in China: Promotion or Inhibition Effect? Sustainability 2023, 15, 16165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożek, J.; Szewczyk, J.; Jaworska, M. Poziom rozwoju gospodarczego województw w ujęciu dynamicznym. Rozw. Reg. I Polityka Reg. 2021, 14, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowy, K. Miasto—Gospodarka. Zarządzanie. Wyzwania. Tom I Podstawy Ekonomiki Miasta—Wprowadzenie; SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, G. The migration accelerator: Labor mobility, housing, and demand. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2020, 12, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntele, I.; Istrate, M.; Horea-Șerban, R.I.; Banica, A. Demographic resilience in the rural area of Romania. A statistical-territorial approach of the last hundred years. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fala, A. The first and second demographic dividends in Moldova. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 2, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsham, N.; Rowe, F. The Demographic Causes of European Sub-National Population Declines. Eur. J. Popul. 2025, 41, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshof, H.; Van Wissen, L.; Mulder, C.H. The self-reinforcing effects of population decline: An analysis of differences in moving behaviour between rural neighbourhoods with declining and stable populations. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 36, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkal, J. On the Analysis of a Set of Characteristics. Appl. Math. 1960, 5, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Męczyński, M.; Konecka-Szydłowska, B.; Gadziński, J. Poziom Rozwoju Społeczno-Gospodarczego i Klasyfikacja Małych Miast w Wielkopolsce; Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Konecka-Szydłowska, B. Zróżnicowanie małych miast województwa wielkopolskiego ze względu na poziom rozwoju społeczno–gospodarczego. Stud. Miej. 2012, 8, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Uglis, J. Ocena poziomu rozwoju społeczno-gospodarczego gmin wiejskich województwa wielkopolskiego. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2013, 281, 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, H.; Waśniewska, A. Application of the Perkal method for assessing competitiveness of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Oeconomia Copernic. 2017, 8, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revko, A.; Butko, M.; Popelo, O. Methodology for Assessing the Influence of Cultural Infrastructure on Regional Development in Poland and Ukraine. Comp. Econ. Research. Cent. East. Eur. 2020, 23, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawiak, A. Analiza atrakcyjności małych miast województwa łódzkiego pod względem rozwoju lokalnej przedsiębiorczości. Przedsiębiorczość-Eduk. 2022, 18, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józefowicz, K. Starość demograficzna miast województwa wielkopolskiego w latach 1995–2018. Rozw. Reg. I Polityka Reg. 2019, 48, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, A. Postrzeganie srebrnej gospodarki w kontekście wyzwań związanych ze starzejącą się populacją w ujęciu lokalnym. Stud. przypadku. Ekon. Wroc. Econ. Rewiew 2020, 26, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ja’afar, R. Demographic transition and economic potential: Malaysia. SCMS J. Indian Manag. 2020, XVII, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowska-Kmon, A. O nowych miarach zaawansowania procesu starzenia się ludności. Stud. Demogr. 2011, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kowaleski, J.T. Kwestie Metodologiczne w Badaniu Procesu Starzenia się Ludności. In Procesy Demograficzne u Progu XXI Wieku. Polska a Europa; Strzelecki, Z., Ed.; RRL: Warszawa, Poland, 2003; pp. 306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Travassos, G.F.; Coelho, A.B.; Arends-Kuenning, M.P. The elderly in Brazil: Demographic transition, profile, and socioeconomic condition. Rev. Bras. Estud. Popul. 2020, 37, e0129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlke, P. Samorząd Terytorialny w Procesie Kształtowania Rozwoju Gospodarczego Regionu na Przykładzie Województwa Wielkopolskiego. In Wydawnictwo Państwowej Wyższej Szkoły Zawodowej im; Stanisława Staszica w Pile: Piła, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kamińska, W.; Ossowski, W. Wieloaspektowa ocena procesów starzenia się ludności na obszarach wiejskich w Polsce. Biul. KPZK 2017, 267, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, A. Rozwój wsi i Rolnictwa w Polsce. Aspekty Przestrzenne i Regionalne; IRWiR: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sobala-Gwosdz, A.; Janas, K.; Jarczewski, W.; Czakon, P. Hierarchia Funkcjonalna Miast w Polsce i jej Przemiany w Latach 1990–2020; Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Warszawa–Kraków, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Perdał, R.; Churski, P.; Herodowicz, T.; Konecka-Szydłowska, B. Cities in polarised socio-economics space of Poland. Stud. Miej. 2020, 34, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, R.; Mazur, M.; Śleszyński, P.; Szejgiec-Kolenda, B. Wpływ Zmian Demograficznych w Polsce na Rozwój Lokalny = Impact of Demographic Changes in Poland on Local Development; IGiPZ PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; Volume 274. [Google Scholar]

- Ambinakudige, S.; Parisi, D. A spatiotemporal analysis of inter-county migration patterns in the United States. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2017, 10, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, M.; Cividino, S.; Turco, R.; Salvati, L. Population age structure, complex socio-demographic systems and resilience potential: A spatio-temporal, evenness-based approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fothergill, S.; Houston, D. Are big cities really the motor of UK regional economic growth? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2016, 9, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Clayton, N.; Tochtermann, L.; Hildreth, P.; Marshall, A.; Brown, H.; Barnett, S. City Relationships: Economic Linkages in Northern City-Regions; One North East on Behalf of The Northern Way: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.; Gardiner, B.; Tyler, P. The Evolving Economic Performance of UK Cities: City Growth Patterns, 1981–2011; Working Paper, Foresight Programme on the Future of Cities; UK Government Office for Science: London, UK, 2014.

- Turok, J.; Mykhnenko, V. The Trajectories of European Cities, 1960–2005. Cities 2007, 24, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.M.; Lichter, D.T. Rural depopulation: Growth and decline processes over the past century. Rural Sociol. 2019, 84, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotschy, R.; Bloom, D.E. Population Aging and Economic Growth: From Demographic Dividend to Demographic Drag? NBER Working Paper; NBER: Cambridge, UK, 2023; p. 31585. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Lv, L.; Failler, P. The impact of population aging on economic growth: A case study on China. AIMS Math. 2023, 8, 10468–10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedwab, R.C.; Pereira, D.; Roberts, M. Cities of Workers, Children, or Seniors? Age Structure and Economic Growth in a Global Cross-Section of Cities. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume No. 9040, Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3485924 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Vîlcea, C.; Popescu, L.; Clincea, A. Does Shrinking Population in Small Towns Equal Economic and Social Decline? A Romanian Perspective. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszke, M.; Oleńczuk-Paszel, A.; Sompolska-Rzechuła, A.; Śpiewak-Szyjka, M. Demographic Change and the Housing Stock of Large and Medium-Sized Cities in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. Golden Age Index; PwC: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Flaszyńska, E.; Męcina, J. Aktywne starzenie się jako wyzwanie dla rynku pracy w Polsce i w pozostałych krajach Europy. Ubezpieczenia Społeczne Teor. Prakt. 2021, 150, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Indicator | Definition | Source | Variable Nature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | old-age rate | The percentage of individuals of post-working age (60 years and older in the case of women and 65 years and older for men) in the total population (%) | [33,38,39,40] | D |

| X2 | old-age dependency ratio | The ratio of individuals of post-working age per 100 individuals of working age (persons) | [8,10,15,34,41] | D |

| X3 | parent support ratio | The number of individuals aged 85 and older per 100 individuals aged 50–64 years (persons) | [41] | D |

| X4 | Potential support ratio (inverse old-age dependency ratio) | The ratio of working-age individuals to individuals of post-working age (persons) | [42] | S |

| X5 | Dependency ratio | The ratio of the number of children (aged 0–14 years) and older people (aged 65 years and older) to the number of individuals aged 15–64 years (persons/100 working-age people) | [10,12,43] | D |

| Type | Aspect | Types of Small Towns | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | PA | |||

| I | + | + | Economically competitive and relatively young | A high level of economic competitiveness and a low progression of population aging |

| II | + | − | Economically competitive and aging | A high level of economic competitiveness and a high progression of population aging |

| III | − | + | Economically uncompetitive and relatively young | A lower level of economic competitiveness and a low progression of population aging |

| IV | − | − | Economically uncompetitive and aging | A lower level of economic competitiveness and a high progression of population aging |

| Type | Stage of Population Aging | Values of Metrics | 2004–2006 | 2011–2013 | 2017–2019 | 2020–2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| I | very low | above 2.000 | 2 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| II | low | 1.001 to 2.000 | 58 | 52.7 | 11 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| III | medium-low | 0 to 1.000 | 46 | 41.8 | 86 | 78.2 | 13 | 11.8 | 3 | 2.7 |

| IV | medium-high | −0.999 to 0 | 4 | 3.6 | 13 | 11.8 | 82 | 74.5 | 54 | 49.1 |

| V | high | −2.000 to −0.100 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 12.7 | 48 | 43.6 |

| VI | very high | below −2.000 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 5 | 4.5 |

| Type | Aspect | Types of Small Towns | Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | PA | 2004–2006 | 2011–2013 | 2017–2019 | 2020–2021 | ||

| I | + | + | Economically competitive and relatively young | 31.8% | 40.0% | 6.4% | 1.8% |

| II | + | − | Economically competitive and aging | 1.8% | 6.4% | 52.7% | 60.0% |

| III | − | + | Economically uncompetitive and relatively young | 64.5% | 48.2% | 3.6% | 0.9% |

| IV | − | − | Economically uncompetitive and aging | 1.8% | 5.5% | 37.3% | 37.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Józefowicz, K. Population Aging and Economic Competitiveness in Polish Small Towns. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4619. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104619

Józefowicz K. Population Aging and Economic Competitiveness in Polish Small Towns. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4619. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104619

Chicago/Turabian StyleJózefowicz, Karolina. 2025. "Population Aging and Economic Competitiveness in Polish Small Towns" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4619. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104619

APA StyleJózefowicz, K. (2025). Population Aging and Economic Competitiveness in Polish Small Towns. Sustainability, 17(10), 4619. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104619