The Impact of VR/AR-Based Consumers’ Brand Experience on Consumer–Brand Relationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR vs. AR)

2.2. Brand Experience

2.3. Consumer–Brand Relationships

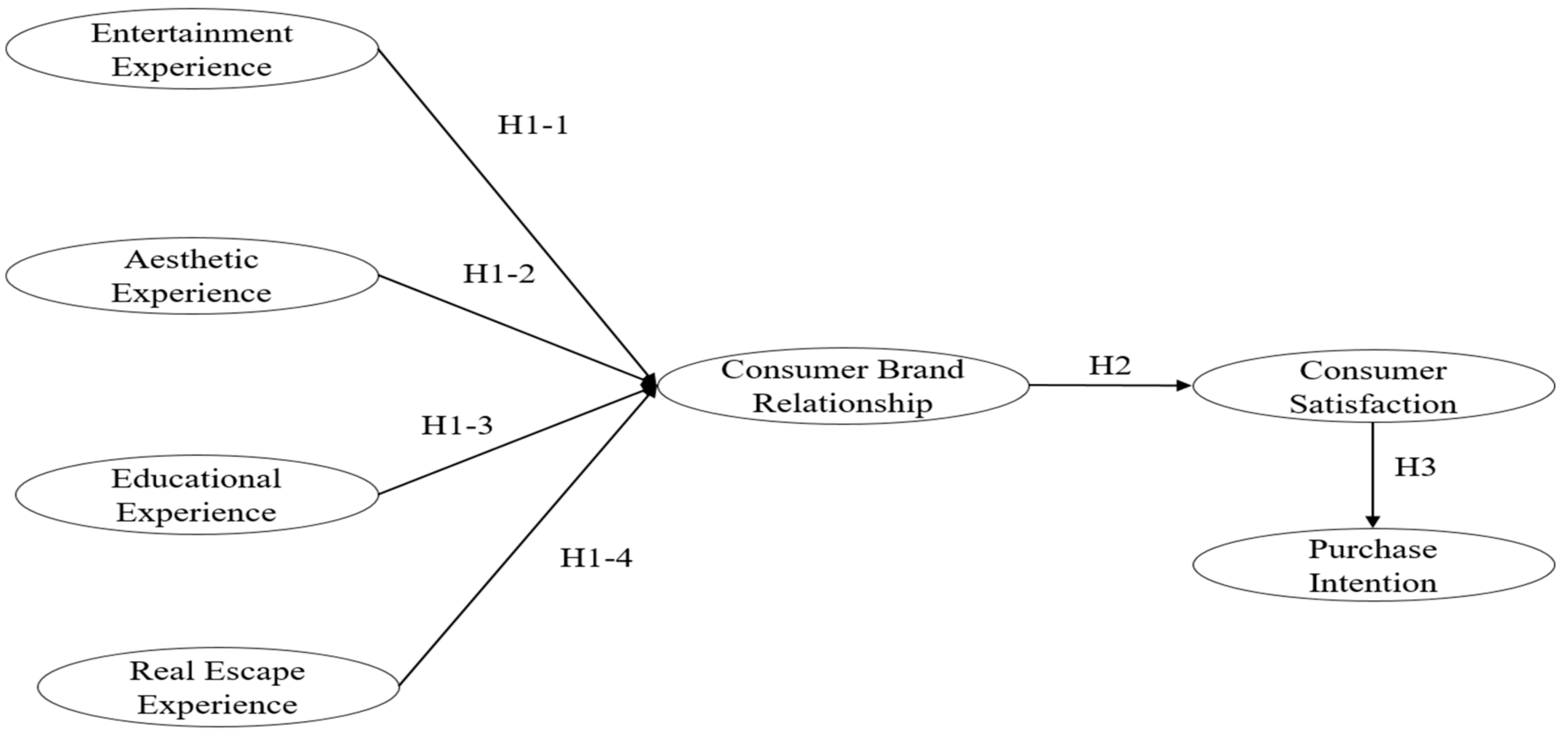

3. Hypotheses and Theoretical Model

3.1. Hypotheses

3.2. Research Model

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Operational Definitions and Variable Measures

4.2. Survey Procedure and Data Collection

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Measurement Validity

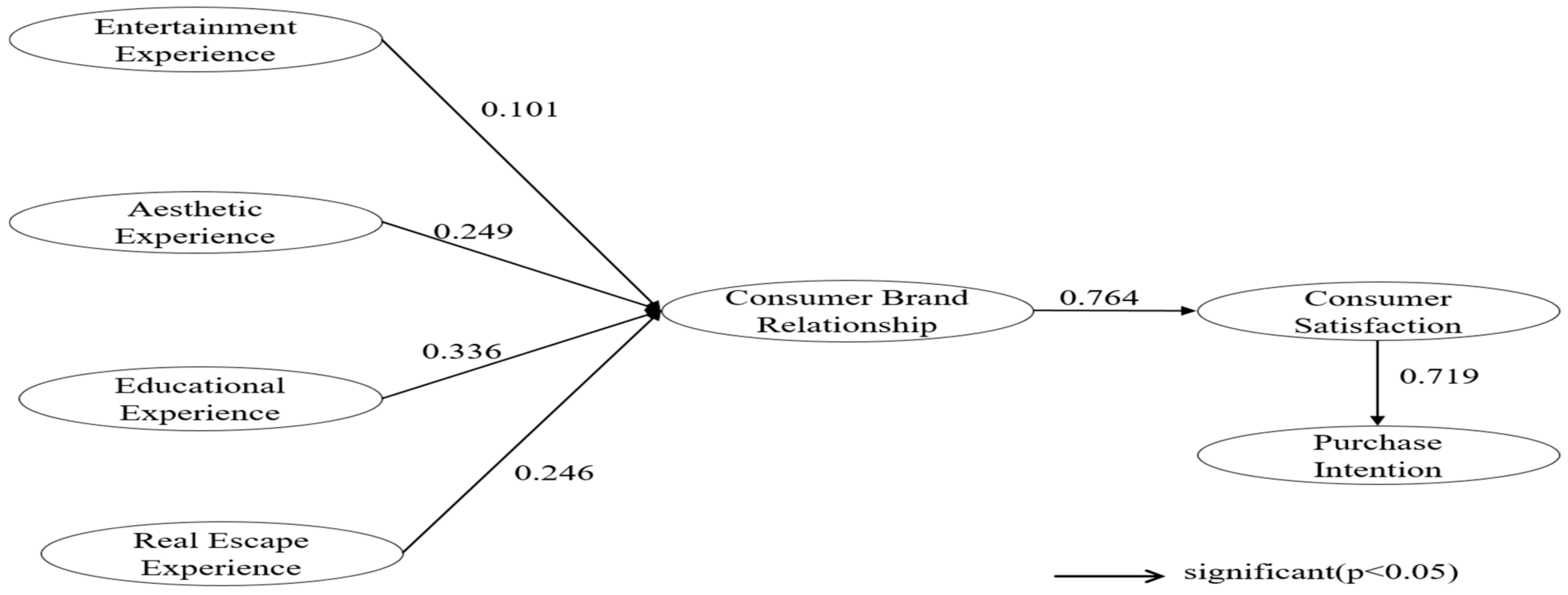

5.3. Hypothesis Testing

5.4. Moderating Effects of Authenticity

6. Conclusions and Discussion

7. Implications and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slater, M. Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behavior in immersive virtual environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Natl. Cent. Biotechnol. Inf. 2009, 364, 3549–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, S.S.; Xu, Q.; Bellur, S. Designing interactivity in media interfaces: A communications perspective. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010; ACM: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 2247–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrebroeck, H.V.; Brengman, M.; Willems, K. Escaping the crowd: An experimental study on the impact of a Virtual Reality experience in a shopping mall. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Green, T. Virtual reality: Low-cost tools and resources for the classroom. TechTrends 2016, 60, 517–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipresso, P.; Giglioli, I.A.C.; Raya, M.A.; Riva, G. The past, present, and future of virtual and augmented reality research: A network and cluster analysis of the literature. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipresso, P.; Serino, S.; Riva, G. Psychometric assessment and behavioral experiments using a free virtual reality platform and computational science. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markets and Markets. AR and VR Display Market. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5319533/ar-and-vr-display-market-by-device-type-ar-hmds#sp-pos-4 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Interactions Consumer Experience Marketing. The Impact of Augmented Reality on Retail. Available online: http://www.retailperceptions.com/wp-content/uploads/Retail_Perceptions_Report_2016_10.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Bonetti, F.; Warnaby, G.; Quinn, L. Augmented reality and virtual reality in physical and online retailing: A review, synthesis and research agenda. In Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality: Empowering Human, Place and Business; Jung, T., Dieck, M., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2018; pp. 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bailenson, J.N.; Yee, N.; Merget, D.; Schroeder, R. The effect of behavioral realism and form realism of real-time avatar faces on verbal disclosure, nonverbal disclosure, emotion recognition, and copresence in dyadic interaction. Presence 2006, 15, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biocca, F.; Harms, C.; Gregg, J. The networked minds measure of social presence: Pilot test of the factor structure and concurrent validity. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual International Workshop on Presence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 21–23 May 2001; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, M.; Sanchez-Vives, M.V. Enhancing our lives with immersive virtual reality. Front. Robot. AI 2016, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, R.; Baillot, Y.; Behringer, R.; Feiner, S.; Julier, S.; MacIntyre, B. Recent advances in augmented reality. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2001, 21, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyon, D.; Smyth, M.; O’Neill, S.; McCall, R.; Carroll, F. The place probe: Exploring a sense of place in real and virtual environments. Presence 2006, 15, 668–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.M. New method to measure end-to-end delay of virtual reality. Presence Teleoper. Virtual Environ. 2010, 19, 585–600. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, T.J.; Mohler, B.J.; Bülthoff, H.H. Talk to the virtual hands: Self-animated avatars improve communication in head-mounted display virtual environments. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirico, A.; Giovannetti, T.; Neroni, P.; Simone, S.; Gallo, L.; Galli, F.; Giancamilli, F.; Predazzi, M.; Lucidi, F.; De Pietro, G.; et al. Virtual reality for the assessment of everyday cognitive functions in older adults: An evaluation of the Virtual Reality Action Test and two interaction devices in a 91-year-old woman. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javornik, A. Augmented reality: Research agenda for studying the impact of its media characteristics on consumer behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G.; Wilson, A. Shopping in the digital world: Examining customer engagement through augmented reality mobile applications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 210–224. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Guerreiro, J.; Eloy, S.; Langaro, D.; Panchapakesan, P. Understanding the use of virtual reality in marketing: A text mining-based review. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Stangl, B. Augmented reality experiences and sensation seeking. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104023. [Google Scholar]

- Supriyadi, H. Augmented reality technology (AR) as alternative media for promotional product. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Brakus, J.J.; Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does It Affect Loyalty? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloza, A. Brand engagement and brand experience at BBVA, the transformation of a 150 years old Company. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2008, 11, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Silva, P.M.; Moutinho, V.M. The effects of brand experiences on quality, satisfaction and loyalty: An empirical study in the telecommunications multiple-play service market. Innovar 2017, 27, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambler, T.; Bhattacharya, C.; Edell, J.; Katherine, L.; Vikas, M. Relating brand and customer perspectives on marketing management. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 5, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeong, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.; Zehir, C.; Kitapçi, H. The effects of brand experience and service quality on repurchase intention: The role of brand relationship quality. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 11190–11201. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theater & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B. Customer Experience Management: A Revolutionary Approach to Connecting with Your Customers; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi, J.A.; Hite, R.E. Environmental color, consumer feelings, and purchase likelihood. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 9, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorn, G.J.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Yi, T.; Dahl, D.W. Effects of color as an executional cue in advertising: They’re in the shade. Manag. Sci. 1997, 43, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers-Levy, J.; Peracchio, L.A. Moderators of the impact of self-reference on persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, F.S.; Wang, C.C.; Lai, M.C.; Tung, C.H.; Yang, Y.J.; Tsai, K.H. Persuasiveness of organic agricultural products: Argument strength, health consciousness, self-reference, health risk, and perceived fear. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1289–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P. The effects of brand relationship norms on consumer attitudes and behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, N.H.A.; Tuhin, M.K.W. Consumer brand relationships. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2016, 6, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Lehmann, D.R. Brands and branding: Research findings and future priorities. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of brand personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I.; Taylor, D.A. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships; Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut, J.W.; Kelley, H.H. The Social Psychology of Groups. 1959. Available online: https://archive.org/details/socialpsychology00thib (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Skalski, P.; Tamborini, R. The role of social presence in interactive agent-based persuasion. Media Psychol. 2007, 10, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusbult, C.E. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 16, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior in Elementary Forms. A Primer of Social Psychological Theories; Brooks/Cole Publishing Company: Monterey, CA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Foa, U.G.; Foa, E.B. Societal Structures of the Mind; Charles C. Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Evard, Y.; Aurier, P. Identification and validation of the components of the person–object relationship. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 37, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yan, K.; Lu, S.; Jia, H.; Xie, D.; Yu, Z.; Guo, X.; Huang, F.; Gao, W. Part-aware progressive unsupervised domain adaptation for person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2020, 23, 1681–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.H.; Yoon, M.S.; Lee, J.Y. The influence of brand color identity on brand association and loyalty. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolao, L.; Irwin, J.R.; Goodman, J.K. Happiness for scale: Do experiential purchases make consumers happier than material purchases? J. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boven, L.; Gilovich, T. To do or to have? That is the question. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.L. Relationship marketing: A high-involvement product attribute approach. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 1998, 7, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential Marketing: How to Get Customers to Sense, Feel, Think, Act and Relate to Your Company and Brands; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Peterson, R.T. Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: The role of switching costs. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantenello, L.; Schmitt, B.H. Using the brand experience scale to profile consumers and predict consumer behavior. J. Brand Manag. 2000, 17, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F.F. The Loyalty Effect: The Hidden Force behind Growth, Profits and Lasting Value; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Witham, M. Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M.; Engen, M. Pine and Gilmore’s concept of experience economy and its dimensions: An empirical examination in tourism. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 12, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Towards understanding members’ general participation in and active contribution to an online travel community. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.; Morgan, M.; Hemmington, N. Online communities and the sharing of extraordinary restaurant experiences. J. Food Serv. 2008, 19, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, R.; Borovicka, M. Developing an Online Business Community: A travel Industry Case Study. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’06), Kauai, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Overby, J.W.; Lee, E.J. The effects of utilitarian and hedonic online shopping value on consumer preference and intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavine, H.; Sweeney, D.; Wagner, S.H. Depicting women as sex objects in television advertising: Effects on body dissatisfaction. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 25, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology 1979, 13, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W.; Cervera-Taulet, A.; Pérez-Cabañero, C. Exploring the links between destination attributes, quality of service experience and loyalty in emerging Mediterranean destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri, D.L. An Experience Economy Analysis of Tourism Development along the Chautauqua-Lake Erie Wine Trail; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Kandampully, J. The role of emotional aspects in younger consumer–brand relationships. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2012, 21, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloutsou, C.L.; Moutinho, L. Brand relationships through brand reputation and brand tribalism. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esch, F.R.; Langer, T.; Schmitt, B.H.; Geus, P. Are brands forever? How brand knowledge and relationships affect current and future purchases. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2006, 15, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S.; Alvarez, C. Research dialogue: Relating badly to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2013, 23, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawle, J.; Cooper, P. Measuring emotion: Lovemarks, the future beyond brands. J. Advert. Res. 2006, 46, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yim, M.Y. Exploring consumers’ attitude formation toward their own brands when in crisis: Cross-national comparisons between USA and China. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Sullivan, M. The antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction for firms. Mark. Sci. 1993, 12, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, M.M.; Karson, M.I. Analysis of Purchase Intent Scales Weighted by Probability of Actual Purchase. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, W.; Kalra, A.; Staelin, R.; Zeithaml, V.A. A dynamic process model of service quality: From expectations to behavioral intentions. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Monroe, K.B.; Krishnan, R. The effects of price-comparison advertising on buyers’ perceptions of acquisition value, transaction value and behavioral intentions. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bleize, D.; Antheunis, M.L. Factors influencing purchase intent in virtual worlds: A review of the literature. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.; Cudmore, B.; Hill, R. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Guihan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The effect of corporate social responsibility activities on companies with bad reputations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 15, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Suprawan, L. Metaverse Meets Branding: Examining Consumer Responses to Immersive Brand Experiences. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index (n = 518) | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 254 | 49.0 |

| Female | 264 | 51.0 | |

| Age | 20–29 years | 99 | 19.1 |

| 30–39 | 111 | 21.4 | |

| 40–49 | 98 | 18.9 | |

| Over 50 years | 121 | 23.4 | |

| Education Level | High school level | 89 | 17.2 |

| College students | 130 | 25.1 | |

| College level | 60 | 11.6 | |

| Graduate school level | 285 | 55.0 | |

| Monthly Income (in US$) | Below $2000 | 43 | 8.3 |

| $2000–$3000 | 194 | 37.5 | |

| $3000–$4000 | 127 | 24.5 | |

| $4000–$5000 | 76 | 14.7 | |

| Over $5000 | 55 | 10.6 | |

| Variables (Cronbach’s Alpha) | Items | Communality | Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Entertainment (0.928) | En1 | 0.785 | 0.837 | |||

| En2 | 0.818 | 0.853 | ||||

| En3 | 0.803 | 0.822 | ||||

| Aesthetic (0.806) | Es1 | 0.647 | 0.823 | |||

| Es2 | 0.732 | 0.724 | ||||

| Es3 | 0.733 | 0.663 | ||||

| Education (0.740) | Ed1 | 0.637 | 0.739 | |||

| Ed2 | 0.719 | 0.692 | ||||

| Ed3 | 0.640 | 0.718 | ||||

| Real Escape (0.792) | Re1 | 0.679 | 0.756 | |||

| Re2 | 0.726 | 0.718 | ||||

| Re3 | 0.687 | 0.736 | ||||

| Eigenvalues | 9.215 | 4.124 | 2.907 | 1.786 | ||

| % of variance | 51.79 | 9.369 | 7.560 | 6.549 | ||

| Total variance extracted | 22.54 | 40.41 | 58.2 | 75.3 | ||

| KMO = 0.905, Bartlett’s Sphericity Test χ² = 3643.1(df = 66, p = 0.000) | ||||||

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entertainment | 0.662 | ||||||

| Esthetic | 0.403 | 0.692 | |||||

| Education | 0.332 | 0.397 | 0.623 | ||||

| Real Escape | 0.345 | 0.349 | 0.333 | 0.675 | |||

| CBR | 0.381 | 0.307 | 0.338 | 0.282 | 0.698 | ||

| CS | 0.161 | 0.211 | 0.248 | 0.152 | 0.584 | 0.682 | |

| PI | 0.112 | 0.169 | 0.275 | 0.158 | 0.607 | 0.253 | 0.517 |

| H | Paths | Coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| H1-1 | Entertainment → CBR | 0.101 ** (0.091)/z = 1.997, p = 0.044 |

| H1-2 | Aesthetic → CBR | 0.249 *** (0.286)/z = 5.280 |

| H1-3 | Education → CBR | 0.336 *** (0.381)/z = 7.136 |

| H1-4 | Real Escape → CBR | 0.246 *** (0.267)/z = 5.260 |

| H2 | CBR → CS | 0.764 *** (0.703)/z = 26.87 |

| H3 | CS → PI | 0.719 *** (0.781)/z = 23.50 |

| Goodness of Fit: χ² = 9832.3, df = 543, p = 0.000, CFI = 0.936, GFI = 0.888, AGFI = 0.855, NFI = 0.906, NNFI = 0.907, RMSEA = 0.061 | ||

| H | Path | Path Coefficient | χ² Modification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | |||

| H3-1 | Entertainment → CBR | 0.269 (0.251)/z = 4.168 | 0.145 (0.106)/z = 1.895 | Δχ² = 8.169, p = 0.000 |

| H3-2 | Aesthetic → CBR | 0.248 (0.287)/z = 3.644 | 0.097 (0.092)/z = 1.331 | Δχ² = 9.609, p = 0.000 |

| H3-3 | Education → CBR | 0.272 (0.261)/z = 3.756 | 0.219 (0.203)/z = 2.756 | Δχ² = 12.87, p = 0.000 |

| H3-4 | Real Escape → CBR | 0.381 (0.445)/z = 5.243 | 0.119 (0.100)/z = 1.784 | Δχ² = 9.250, p = 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, J.-Y.; Xing, Y.; Jin, C.-H. The Impact of VR/AR-Based Consumers’ Brand Experience on Consumer–Brand Relationships. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097278

Zeng J-Y, Xing Y, Jin C-H. The Impact of VR/AR-Based Consumers’ Brand Experience on Consumer–Brand Relationships. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097278

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Jing-Yun, Yisitie Xing, and Chang-Hyun Jin. 2023. "The Impact of VR/AR-Based Consumers’ Brand Experience on Consumer–Brand Relationships" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097278

APA StyleZeng, J.-Y., Xing, Y., & Jin, C.-H. (2023). The Impact of VR/AR-Based Consumers’ Brand Experience on Consumer–Brand Relationships. Sustainability, 15(9), 7278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097278