Abstract

This study aims to understand how the characteristics of the luxury brand influencer and consumer need satisfaction positively affect the self-brand connection. It also attempts to understand the relationship between self-brand connection and word-of-mouth intention. This study also investigates the moderating effect of self-identification and product fit as control variables. The hypothesis and research model in this study are established through a literature review. Furthermore, 500 consumers who use the Internet and social networking services participated in this study. The statistical package and structural equation analysis program were used to test the hypothesis. The results from analyzing the hypothesis established in this study are as follows: The influencer’s characteristics, such as attractiveness, expertise, and reliability were found to have a positive effect on the self-brand connection. The study also investigated that autonomy, as a component of consumer need satisfaction, did not positively affect the self-brand connection. However, relatedness and competence positively affected the self-brand connection. The self-identification and product fit have moderating effects when influencers’ characteristics and consumer need satisfaction affect the self-brand connection. It was confirmed that there was an interaction effect between the high and low groups for all modulating variables. The implications of the study were mentioned from a sustainability perspective in the implications at the end of the paper.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, social networking services (SNS) have been commercialized in a way that has seen the original purpose of interpersonal networking transformed into a major platform for brand content [1]. Many brands use media influencers to introduce new products and announce special promotions. Media influencers recommend products using their SNS pages and share links to shopping websites [2]. The influencer tests whether fashion brand advertisers can have discriminatory effects when they appear as human models on advertising brands’ official Instagram profiles. A social media influencer is a popular SNS user who has established a considerable following. An influencer has one or more activated Internet or SNS accounts and a considerable number of followers. Media influencers are active across various brands (fashion, beauty, and lifestyle), and they are reliable and appealing to followers [3,4,5].

Fashion brands typically use fashion influencers who have numerous followers. These influencers present audiences who follow and perceive them favorably with reliable explanations of fashion brands and opinions on products [6,7]. Users can devise a fashion brand strategy to see brand-related content embedded in popular influencers’ daily stories and posts [8]. Influencer marketing has become such an essential feature of fashion and beauty brands that brands and agencies employ influencer experts and online services with the sole purpose of recruiting and verifying effective influencers [9,10]. The branding results of social media posts by fashion influencers have been the subject of many studies aimed at identifying the content characteristics of such posts (compared to social media posts by commercial fashion brands), as well as the psychological mechanisms explaining why people respond favorably to social media fashion influencers [9].

The development of information technology and advances in social media content production tools have also brought about many changes with respect to marketing communication methods. Among them, an important change is influencer marketing: a marketing activity using digital media creators. From a corporate perspective, influencer marketing is actively used to improve the corporate image and brand awareness in line with the social painting cultural trend.

Marketing using influencers is a digital marketing strategy that attracts attention because it can create solid relationships with potential customers and produce further marketing content to develop trust among consumers. An influencer is an ordinary person; however, based on their knowledge and expertise with respect to a specific topic, they have built trust-based relationships with many social media audiences. Influencers exert significant sway on decisions made by the general public, as well as their followers [6]. Forming a steady relationship with an influencer can help to harmonize a product’s branding with the influencer, in turn affecting the brand’s organic exposure within the content. In particular, the prevalence of marketing activities using YouTube influencers is steadily increasing. YouTube is evaluated as having marketing effects in that, not only does it include interactive and bidirectional SNS, but it can also diversify services and channels and appeal to users through audio–visual content.

As the role of influencers in the market grows, many companies are expanding their investment in influencer marketing, and related studies are also appearing with increasing frequency. Previous studies have mainly revealed factors that affect consumer responses to influencers and the associated content [6,7,8,9]. Although practical applications of social media (e.g., SNS, etc.) are multiplying, specific research on how brand communication marketing activities utilize such media is insufficient. Marketers expect famous influencers to positively influence consumer behavior and attitude formation such as revisits and purchases; however, research on the situations and factors that affect consumers when they make strategic decisions is lacking [9]. With the recent increase in interest in influencers, several related studies have been conducted. Previous studies have been focused on the effect of influencers. However, the casual relationship between influencers’ characteristics and consumer behavior has not been investigated by applying the SOR model.

Thus, the aim of this study is to break from the existing research framework and examine the relationship between influencers and consumer responses by applying constructs such as self-brand connection, word-of-mouth intention, self-identification, and product fit. With this study, we aim to understand the relationship between the characteristics of famous luxury brand influencers, the self-brand connection, and consumer need satisfaction. In addition, we intend to understand the relationship between the self-brand connection and the recommendation intention. Furthermore, with this study, we seek to examine the moderating effect by setting self-identification and product fit as control variables. Grasping this causal relationship will make it possible to present meaningful implications with respect to which marketing strategies companies should establish in the future to build strong consumer relationships through social media influencers.

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Use and Gratification Theory and SOR Model

The relationship between media use and gratification has long been employed in several media vehicles in order to predict how readers and viewers use the news presented to them via different media outlets (i.e., television, radio, the Internet, etc.). Some scholars have pointed out that use and gratification is a media use paradigm derived from mass communication research that guides the assessment of consumer motivations for media usage and access. Scholars have also emphasized that use and gratification is one of the essential theories used to understand consumer motivations for media use and has been applied to identify and profile audience motivations for the use of radio and early television media [11]. Several studies have been conducted on the relationship between media usage and the motivations of users, which include social escapism, transactional security and privacy, information, interactive control, socialization, non-transactional privacy, economic motivation, interpersonal utility, pastime motivation, information seeking, convenience, and entertainment [12,13]. Consequently, Internet users have a tendency to recognize the Internet medium as an outlet for socialization, self-expression, information seeking, entertainment, and personal business. These elements of motivation may be applied to social media user behavior.

The SOR (stimuli–organization–response) model is recognized as one of the key theories related to the study and explanation of user behavior. The SOR model has been applied in a variety of research contexts, including information systems, advertising, e-commerce, and education. This model is mainly applied to address user behavior, consumer behavior, and user opinion. In the SOR model, environmental incentives can stimulate an individual’s internal and physical state, which, in turn, can trigger behavioral responses. The SOR theory results in a tendency or avoidance to engage in consumer behavior (R) when an individual elicits an emotional or cognitive response (O) to the external environment (S). The SOR model has been widely applied to the prediction and interpretation of consumer behavior, such as in research on consumer purchase intention and purchase behavior [14,15].

The aim of this study is to introduce the influence of famous influencers and investigate the phenomenon whereby e-commerce platforms use social media to promote consumer consumption. By applying the aforementioned SOR model, we discuss the effect of online influencers on consumer behavior. This study represents an attempt to investigate how these variables affect self-brand connection and word-of-mouth intention by considering the characteristics of influencers and consumer need satisfaction as Poisson variables, and self-identification and product fit as moderating variables. Based on the SOR model, the aim of this study is to consider independent variables as external stimuli, that is, self-identification and product fit as moderating variables and self-brand connection as a consumer response variable, as well as word-of-mouth intention.

2.2. Social Media and Influencer Marketing

Social media has grown rapidly over the past decade and become an indispensable necessity for modern people. More than 3.8 billion people use social media worldwide, an increase of 321 million or 9% from 2019, accounting for 40% of the world’s population. Social media users are said to look for influential people—or influencers—to help them make decisions. Social media influencers are people who have gained fame due to their knowledge and expertise on a particular topic [16,17]. They regularly post on their favorite social media channels and maintain many enthusiastic fans who actively follow their content. Brand owners are attracted to social media influencers because they create trends and guide fans to purchase the products they promote. The term “online influencer” refers to an influencer who has many fans and is popular in the online world, and almost all social media platforms are flooded with such influencers. Currently, the definition of social media is subject to a certain degree of ambiguity. However, the main feature of social media is that it still gives users the ability to create and disseminate content. Users are content producers, consumers, and propagators.

For example, one can publish what one saw and heard on Facebook and write a product review. Social media is defined in several ways, and although there are differences in the methods of expression, there are common implications [16]. Social media refers to content production and exchange platforms based on user relationships on the Internet, representing a tool or platform used to share opinions, views, experiences, and perspectives among people. The main such social networking platforms are Weibo, WeChat, blogs, Facebook, and Twitter. The spread of information has become important for viewing the Internet, and traditional media is scrambling to stay abreast as issues arise in social life. Large social networks and voluntary transmission are the two main factors that constitute social media.

Social media marketing provides customized marketing information to consumers, and brands reach their followers directly by advertising through marketing accounts on social platforms such as Instagram [16,17]. When a consumer posts news of interest or demand for a product on a social platform, they are offered information about or discounts on the product in question. Companies can also target customers and potential customers, and through their status on the social media platform, they can track consumer tastes in real time so that content can be produced according to the target demographic. Most social media marketing users are rumored to be new customers after long customer sharing; therefore, trust costs are low. Therefore, more money must be spent on social media advertising than existing media marketing, and considerable cost savings can be achieved by using platforms through which companies and individuals can interact with low barriers to entry. In particular, social media marketing has become an increasingly popular choice for many brands in the global economic downturn. The status of companies and consumers on social media platforms is equal. Brands encourage consumers to actively provide feedback on their products, and consumers write reviews in response to marketing materials of brands, press the “like” button, and retweet content to their friends, leading to the development of closer connections with consumers, as well as increased brand satisfaction among consumers. The bidirectional nature of social media interactions also allows companies to develop improved products and services.

Social media has developed bases of public interest and technical support. As social media provides an appropriate environment to communicate with respect to issues of identity and taste and expand social relationships, ordinary individuals have become cultural capitalists with influence in the public sphere [16,17]. Influencers have sway with respect to the formation of public opinion online and drawing attention, and their influence on fashion trends is increasing rapidly, along with that of celebrities. Luxury fashion and beauty companies are actively considering influencer marketing activities, and various academic studies are underway regarding their impact on consumer perception and attitudes. An influencer with numerous followers can enter the fashion arena, become an expert in exercising capital, and lose social influence [18]. Influencers must attract new attention, as viewer response tends to decrease when the number of followers exceeds a certain threshold [16,17], and consumers trust sincere influencers.

Currently, many companies are attempting to spread brand services and products through social media. Brand information released by influential users on social media can make it easier for consumers to perceive the overall brand than information released by companies [17]. In terms of how the Internet affects consumers, traditional celebrities no longer have influence, and Internet celebrities can exert greater influence [16]. Therefore, many companies have also begun distributing their products through social media influencers. Influencers on social media are people who gain fame for their knowledge and expertise on specific topics. Famous influencers have a variety of followers. They regularly post videos, live broadcasts, photos, and articles on their favorite social media channels and recommend and review the quality of new products and services. Influencers participate passionately and actively to attract people who closely monitor their perspectives. They also have the ability to influence other people’s purchasing decisions.

2.3. Influencer Characteristics

Recently, many companies and brands have begun conducting marketing activities using social media influencers to promote the sale of products and services; these new marketing tools have emerged in importance along with academia and practice [4,5]. Social media influencers have knowledge, expertise, opinions, or reliable taste in one or more areas. As leaders, they have a significant number of social network followers [2,6]. Therefore, modern companies strive to partner with such influencers, including by providing them with product testing opportunities or by paying for publicity so that their products can be widely promoted through these influencers. The fact that influencer marketing has emerged as a powerful and trendy marketing strategy is not irrelevant to the popularity and spread of social media. Consumers actively participate in electronic word-of-mouth (e-WOM) [19], such as by freely generating and distributing brand-related information through social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube and revealing their brand preferences.

An influencer is defined as an individual with many followers on SNS over whom they exert influence [16,17]. As their influence in the consumer market grows, many retailers are actively introducing influencer marketing. Influencer marketing works because of the characteristics of influencers. Followers feel close to influencers when they encounter content that consistently aligns with their interests on SNS, and a beloved influencer promoting a specific product can lead to a word-of-mouth effect as significant as that which propagates through acquaintances or family [16,17].

There are three main types of influencers [20] with social influence according to their role. The first type is mass media influencers (TV, radio, newspapers, magazines, Internet media, etc.), who have considerable impact. The second type is professional influencers (experts, celebrities, talents, advertising models, etc.) with social influence and experience or knowledge in a particular field with a considerable impact. The third type is personal influencers (the general public), who influence others through information divergence. In a study on the properties of existing influencers, influencers’ attributes were classified in various fields. In the purchase decision-making process, consumers use information on social media and seek more information and advice from other consumers. The information provided by influencers on social media becomes an important source of information that induces consumer behavior by more strongly influencing this consumer decision-making process [21,22,23]. In influencer marketing, the characteristics of influencers as an informant have been treated as a major leading variable of the persuasion effect. The following is a summary of the results of previous studies on the characteristics of influencers’ sources and consumer responses. Set as variables that affect consumer response were the reliability and attractiveness of influencers; the difference between influencer, famous celebrities, and the general public; and the expertise, reliability, and similarity of information sources [24,25]. Fashion and beauty influencers, who became famous through SNS, also served as representative brand models [9,10]. As the influence of influencers grew, many related studies were conducted, and the influencer characteristics commonly presented in previous studies included attractiveness, expertise, and reliability.

2.4. Consumer Needs Satisfaction

As society develops rapidly, “brands” often lead the quality of life. The theory of self-determination suggests that, basically, customers have three things [26,27]. According to Deci and Ryan, the psychological needs that influence consumers’ self-formation, self-integration, and self-control are defined as essential [26,27]. Psychological needs consist of the following: autonomy, competence, and relevance. The demand for autonomy is related to the possibility of a person who chooses to perform a task, and the demand for competence is related to the perception of the person who effectively brings the desired effect and outcome [26,27]. Furthermore, the demand for relevance is related to human beings and is necessary because intimacy and bonding with others [28] are related to the intrinsic motivation and psychological growth process for meeting basic needs. Competency is an important factor for intrinsic motivation. Previous studies have suggested that optimally challenging activities are related to competency awareness [28,29,30]. Based on the self-determination system, emotional bonds between customers and brands are possible when customers have autonomy, competency, and relevance.

These emotional bonds are expected to promote a high level of autonomy, competence and relevance, and positive customer emotions toward the brand [26,27]. Demand behavior for autonomy, competency, and relevance are conveyed through the level of consumer experience [31], practical thinking [32], and relationships [31]. Purchasing experience is related to the customer’s various sensory styles. According to Deci and Ryan, satisfaction, autonomy, competence, and relevance of basic psychological needs are related to intrinsic motivation [30]. Self-determination theory emphasizes the need to consider basic psychological needs for motivation, autonomy, and ability to understand humans [26,27,28,29,30]. Basic psychological demands for autonomy, ability, and relevance are related to the following: it affects the enhancement of intrinsic motivation and attachment.

3. Hypotheses and Theoretical Model

3.1. Hypotheses

What people consume in a particular brand leads to a brand alliance, which can be used to convey their self-concept to others. When this process occurs, the brand is integrated into an individual’s self-concept, called a self-brand connection [33]. Because brands are inherently symbolic, people’s use of a particular brand can reinforce the outward manifestation of their self-concept to others because the brand is used as a tool to convey their identity. The relationship between brands and consumers means that brands are integrated into their self-concept, so consumers also feel a threat to their self-concept when faced with a brand-threatening scandal [34]. Previous studies on self-brand connection have emphasized the role of self-verification or self-improvement in satisfying self-justification needs [34].

Achieving the psychological benefits of using brands is important in meeting such needs, such as social approval and self-expression. These interests take precedence over all other interests because they become basic elements of self-identification and expression. Existing studies show that when an individual has a strong self-brand relationship, negative brand information is interpreted as a personal failure.

According to the results of a study by Cheng et al., people with strong associations when exposed to negative brand information remained unchanged in brand attitude as well as low self-esteem [35]. The authors explain that consumers’ unchanging attitudes toward brands are driven by the need to protect themselves, not by brands, because, for people with strong self-brand connections, the brand is themselves and vice versa. Research results show that strong self-brand connections play an important role in suppressing the impact of negative brand connections after observing the brand’s prominent use. In these studies, people can see that a greater change in attitude after exposure is the result of activating an individual’s defense mechanism because their self-concept was threatened [36,37]. Many previous studies have shown that the attractiveness of information sources enhances persuasion when delivering messages. People are fond of attractive sources or models, which can lead to a positive attitude toward advertising or brands. Among the characteristics of influencers, attractiveness was the factor with the greatest positive effect on content attitudes. The perceived reliability of the information source is based on the provision of objective and unbiased information and the level of consumer perception regarding what knowledge or experience the information provider gives. Reliability can be viewed as a major variable affecting accepting messages from sources and having a positive attitude. The expertise of the source is at the level of perceiving whether the source has the knowledge or ability to convey accurate and correct messages [38]. Ohanian stated that the expertise of celebrity advertising models positively affects purchase intention [39].

Ryan and Grolnic confirmed that respecting individual autonomy in school or satisfying autonomy needs can lead to better performance than controlling individuals [40]. Previous studies suggested that consumers who formed relationships and bonds formed strong attachments to objects that made them feel such emotions so that they felt connected to others and maintained intimate relationships [26,27,28,29,30]. A study on performance and positive feedback by Fisher showed that positive feedback has a stronger influence on internal motivation when an individual feels that the need for competence has been met [41]. Therefore, this study can establish the following hypotheses to determine how influencers’ characteristics and consumer need satisfaction affects the self-brand connection:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Influencers’ characteristics (attractiveness: H1-1, expertise: H1-2, and reliability: H1-3) will have a positive (+) effect on self-brand connection.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The components of consumer need satisfaction (autonomy: H2-1, relatedness: H2-1, and competence: H2-3) will have a positive (+) effect on self-brand connection.

Personal word-of-mouth (PWOM) is an exchange of information between people who know each other. PWOMs are obtained through direct personal communication with the sender. Furthermore, the recipient is aware of the sender’s identity and is often aware of the sender’s taste and preferences arising from regular interactions with the sender. e-WOM or virtual word-of-mouth (WOM) refers to virtual communication using different electronic communication channels between people who have never met in real life. Satisfaction affects their willingness to perform WOM for the restaurants they visit [42]. Therefore, this study can establish the following hypothesis to find out how the self-brand connection affect word-of-mouth intention:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The self-brand connection will have a positive (+) effect on word-of-mouth intention.

In order for an individual to identify with another person or company, the relationship must provide a self-defined purpose for the individual or community [36,37]. In the marketing context, consumer–company identification is defined as follows. The degree to which consumers feel a bond with the company and the aspect of perceived organizational identity are self-repeating and self-justifiable to them. The concept of self plays an important role in brand identification research. When individuals receive negative information about a brand with a strong identity, they develop a resistant attitude toward information to maintain the self-justifiable attitude and belief that is now threatened. This reality is particularly important for people with strong identities because, for these individuals, the brand identity is integrated into the individual’s self-concept.

In summary, the above definition shows that the activation of the defense mechanism is a precursor to biased information processing. Research on brand identification has shown that identification plays an important role in buffering when a brand is involved in a crisis. Similar results are being observed concerning identification and motivational inference theory [43,44], demonstrating that people with low brand discrimination are motivated to achieve accurate conclusions and process information objectively. Concepts similar to consumer–business identification include self-brand connections that emphasize the role of self-concepts in addition to reference groups, which are the main agents that trigger their defense mechanisms when threats to brands are considered threats to self. Recognition suitability represents the similarity between the original and extended product categories. Past studies have found that consistently perceived suitability positively affects consumers’ attitudes toward brand expansion [36,37]. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses to investigate the moderating effect of self-identification and product fit:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The influence of sub-factors of influencers’ characteristics (attractiveness: H4-1, expertise: H4-2, reliability: H4-3) will affect self-identification through the moderating effect of self-identification.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The sub-factors of consumer need satisfaction (autonomy: H5-1, relatedness: H5-2, and competence: H5-3) will affect self-identification through the moderating effect of self-identification.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

The influence of sub-factors of influencers’ characteristics (attractiveness: H6-1, expertise: H6-2, reliability: H6-3) will affect self-identification through the moderating effect of product fit.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

The sub-factors of consumer need satisfaction (autonomy: H7-1, relatedness: H7-2, and competence: H7-3) will affect self-identification through the moderating effect of product fit.

3.2. Research Model

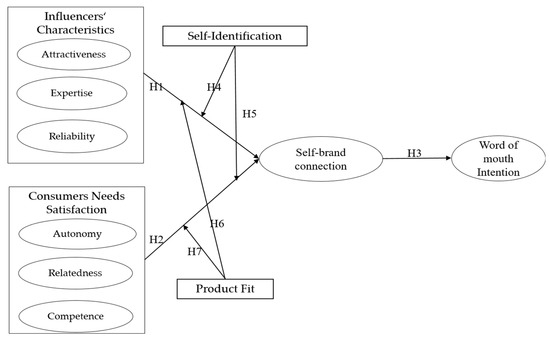

This study’s research model was designed based on the factors influencing the establishment of the self-brand connection by identifying sub-factors of luxury brand influencers’ characteristics and consumer need satisfactions, based on the previous discussions. It also attempts to understand the relationship between self-brand connection and word-of-mouth intention. This study also investigates the moderating effect of self-identification and product fit as control variables. Hypothesis 1 was established to understand how luxury brand influencers’ characteristics and consumer need satisfactions affect the self-brand connection. Hypothesis 2 was established to understand the effect of self-brand connection on word-of-mouth intention. As shown in Figure 1 below, a research model was presented to verify the purpose and hypotheses of this study.

Figure 1.

Suggested research model.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Operational Definition and Measurement of Variables

In this study, the components of the influencers’ characteristics were classified into attractiveness, expertise, and reliability based on the literature and research regarding influencer marketing. An influencer is defined as an individual with many followers and influences them on SNS [2,4,5,6]. In addition, the sub-factors of consumer need satisfaction were classified into autonomy, relatedness and competence based on the literature and research related to the self-determinant theory [26,27,30]. Based on previous research, the components of the influencers’ characteristics and consumer need satisfaction were composed of three items each, and a total of nine items were presented, respectively.

Consumer need satisfaction is a fundamental need of an individual, which may be argued as a universal psychological and consumer need. A total of nine items, three questions each, were presented by revising and supplementing the items used in the previous study [28,29,44]. In this study, “self-brand connection” is defined as the degree to which consumers project a brand into their own self-concept [33,34]. A total of three items were modified and supplemented to suit this study through the existing literature. Three measurement items used in existing studies were used to measure word-of-mouth intention [42].

The questions about self-identification and product fit, established to determine the moderating effect, were reorganized into three questions for the purpose of the study. It is defined as the degree to which the consumer’s self-image and brand image match or the degree to which the self-concept and brand match [45]. Product fit is defined as the extent to which influencers’ characteristics or descriptions conform to the brand [46]. Based on existing studies, it consisted of three items of self-identification and four items of product fit. An operational definition of variables was applied for the questionnaire used in this study.

4.2. Survey Procedure and Data Collection

An operational definition of variables was applied for the questionnaire used in this study. In addition, questionnaire items were extracted from previous studies, and the survey measurement was composed of a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “1” meaning very not, “3” meaning normal, and “5” indicating very yes. In other words, it can be said that the higher the score, the more positive the answer. First, the primary matters for demographic analysis were measured in four items. The measurement details comprised questions on gender, age, education, and income.

The samples were randomly extracted from a list of consumer panels registered with a global research company. In this survey, a survey was conducted on 500 social media influencer content users. For this study, the survey was conducted for about a month, from 15 March to 15 April 2021. A total of 518 people were confirmed to participate in this survey by contacting consumer panels in advance to check whether they participated in a related survey.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

As Shown in Table 1, the final sample consisted of 282 men and 218 women who completed 500 questionnaires. Respondents’ average monthly income was about $3000–4000. Almost all, or 75% of respondents, had college-level degrees. Furthermore, the 30s age group was the largest in the survey, at 24%. This group is the threshold of the demographic distribution of this survey.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

5.2. Measurement Validity

We tested the scales for dimensionality, reliability, and validity using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) before assessing the hypothesized relationships shown in Figure 1. Cronbach’s alpha was higher than 0.7 for all variables. The results of the factor loading, communality, and Cronbach’s alpha are provided in the following Tables. As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, the factor loadings of the items in the measures range from 0.690 to 0.851, demonstrating convergent validity at the item level. The results of the factor analysis for luxury brand influencers’ characteristics and consumer need satisfactions show that the 25 items fall into eight dimensions in Table 2. Eight factors extracted for brand experience were shown to explain 80.1% of the total variance.

Table 2.

Results of factor analysis.

Table 3.

Discriminant and convergent validity.

As shown in Table 3, discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the correlations of components with the average variance extracted (AVE). The AVE falls between 0.597 and 0.698, and the means of the squares of the correlation coefficients fall between 0.110 and 0.593. This result indicates that the AVE is higher than the means of the squares of the correlation coefficients (r2), and also satisfies the requirement of discriminant and convergent validity for research hypothesis model verification.

6. Hypothesis Testing

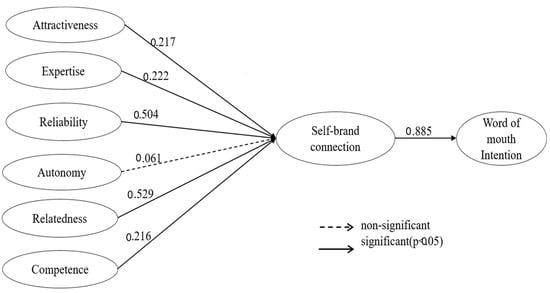

The hypothesized causal paths were estimated to test the structural relationships in the model. The results are shown in Table 4 and Figure 2, and indicate that the components of luxury brand influencers’ characteristics and consumer need satisfaction have positive effects on self-brand connections (γ = 0.217, p < 0.001 for attractiveness; γ = 0.222, p < 0.001 for expertise; γ = 0.504, p < 0.001 for reliability; γ = 0.529, p < 0.001 for relatedness; and γ = 0.216, p < 0.001 for competence). However, autonomy has no positive effects on self-brand connections (γ = 0.061, p = 0.278). Thus, H1-1, 1-2, 1-3, 2-2, and 2-3 were supported, but not 2-1. Additionally, the self-brand connection positively affects word-of-mouth intention (γ = 0.885, p < 0.001). Thus, H3 was supported.

Table 4.

Results of path analysis.

Figure 2.

Path Analysis.

Moderating Effects of Self-Identification and Product Fit

As shown in Table 5, the hypothesized model was estimated separately for each of the two groups (e.g., high and low self-identification and product fit). This study also investigates the moderating effect of self-identification and product fit as control variables. The values of selected fit indexes for the multi-sample analysis of the path model with equality-constrained direct effects are reported in Table 5, which shows the standardized solutions. Generally, standardized path coefficients are used to compare paths within groups. The tests show that the interactions between attractiveness, expertise, reliability, autonomy, relatedness, competence, and self-brand connection for the moderating effect of self-identification (Δχ2 = 1.676, p = 0.094 for attractiveness; Δχ2 = 3.149, p < 0.05 for expertise; Δχ2 = 5.963, p < 0.001 for reliability; Δχ2 = 1.172, p = 0.242 for autonomy; Δχ2 = 7.267, p < 0.001 for relatedness; and Δχ2 = 5.905, p < 0.001 for competence) were significant. The interaction between attractiveness, autonomy and self-brand connection for the moderating effect of self-identification (Δχ2 = 1.172, p = 0.242 for autonomy) was not significant. Thus, H4-1, 4-2, 4-3, H5-2, and 5-3 were supported, but not H5-1. Consumers report that influencers’ rich experience, truthful appearance, and charm affect the formation of intimacy with brands, depending on the degree of similarity in terms of the values and image of influencers. Self-identification can be said to play a moderating role in the relationship whereby the attractiveness, expertise, and reliability of influencers influence self-brand connectivity.

Table 5.

Results of moderating effects of self-identification and product fit.

The tests show that the interactions between attractiveness, expertise, reliability, autonomy, relatedness, competence, and self-brand connection on the moderating effect of product fit (Δχ2 = 4.379, p < 0.001 for attractiveness; Δχ2 = 7.465, p < 0.001 for reliability; Δχ2 = 12.15, p < 0.001 for relatedness; Δχ2 = 2.710, p < 0.05 for competence) were significant. The interactions between attractiveness, autonomy, and self-brand connection on the moderating effect of self-identification (Δχ2 = 0.916, p = 0.360 for expertise; and Δχ2 = 0.375, p= 0.708 for autonomy) were not significant. Thus, H6-1, 6-3, 7-2, and 7-3 were supported, but not H6-2 and H7-1. Among the variables of consumer satisfaction, self-identification and product fit were found to not play a moderating role in the relationship between autonomy and self-brand connectivity. Consumers are free to collect and communicate information in SNS environments, but these emotions do not affect their attitudes toward brands, which do not change depending on the degree of self-identification and product fit.

7. Conclusions and Implications

7.1. Conclusions

A summary of the results of the analysis of the hypotheses applied in this study is provided below. The components of influencers’ characteristics such as attractiveness, expertise, and reliability were found to have a positive effect on self-brand connection. Competence, as a component of consumer satisfaction needs, was found to positively affect self-brand connection. However, autonomy was not found to have a positive effect on self-brand connection, and the personal characteristics of influencers and the components of consumers’ needs satisfaction were determined to be closely related to self-brand connection. Self-brand connection was found to affect word-of-mouth intention.

In this study, we examined the characteristics of influencers and the impact on consumers’ self-brand connection. Consumers find common ground with brands introduced by influencers, as influencers are perceived as attractive and likable. In addition, the stronger the trust and belief in influencers, the more relatable consumers find brands. The reliability of influencers affects the formation of attitudes toward brands by consumers who feel that they provide true information in the SNS environment [24,25]. In previous studies, the expertise of information sources or advertising models was found to have a significant effect on the intention to purchase products [47]. However, in this study, we found that the richer the experience or professional intellectual ability or competence of influencers, the more consumers relate to and identify with brands. Among the variables of consumer satisfaction, autonomy was found to have a meaningless relationship with self-brand connection. Consumers can feel free emotions in an environment where they can access the information they want regardless of time and place and communicate in two directions; however, these emotions do not affect immersion, homogeneity, and similarity of the brand.

Therefore, it is necessary to develop entertainment elements and content that can actively communicate and encourage followers to make purchases and interact with influencers to satisfy the needs of the relationship. Consumers form relationships with influencers or other followers on SNS and experience competence through interaction, as manifested through faith and trust in influencers. In addition, in order to satisfy the desire for competence, a strategy is needed to induce a sense of achievement or challenge fulfilled through consumer efforts. A multisample analysis was conducted to determine the moderating effect of self-identification on product fit. Furthermore, self-identification and product fit were found to play a controlling role with respect to the effect of influencers’ characteristics and consumer need satisfaction on self-brand connection. The path coefficient of the group with low self-identification and product fit increased in the path coefficient of the group with high self-identification and product fit. As a result of the analysis, an interactive effect was discovered between the high/low separated groups for all moderating variables. A moderating effect was discovered on self-identification and product fit. The higher the self-identification with the influencer, the stronger the effect the influencer’s characteristics were found to have on self-brand connection. In addition, the higher the product fit with the influencer, the stronger the effect of the influencer’s characteristics on the self-brand connection. Therefore, the degree of similarity between self-image and the brand and the degree of product conformity with the influencer are important to connect consumers’ self-image with influencers and brands.

7.2. Implications

This study is significant because it provides various academic and practical implications that can be divided into two areas. First, regarding the academic implications, this study is considered meaningful in that it considers current trends in the media and consumer social and cultural environments. With the emergence of personalized media due to the development of social media, products and services can be released through single-person Internet broadcasting and various media platforms. In the context of this trend, media such as YouTube Internet broadcasts, in which ordinary people, celebrities, politicians, and sports stars are provided with products or services that they broadcast, are widespread. Currently, accurate research on influencers, who are active in such media, is also believed to contribute to the field.

First, it was discovered that the attractiveness of influencers affects the self-brand connection. Influencers can be said to receive attention from consumers only when they receive positive ratings in terms of attractiveness, favorability, refinement, and first impression. Not only do consumers like the content in which influencers have appeared, but in such cases, consumers feel close to the introduced brand. Influencers and brands with high levels of attractiveness are similar to the consumer’s ego and are homogeneous. Furthermore, it can be said that consumers hope that influencers have experience or expertise with respect to brands or services. Judging from influencers’ expertise and richness of experience, consumers also sympathize with them and brands that align with their egos. Human belief or trust in influencers is considered one of the most important factors according to which consumers evaluate influencers. The higher the level of trust or belief, the more favorable consumer attitudes are toward presented products or services. Additionally, consumers perceive brands introduced by the influencer in terms of high faith or trust, similar to an individual’s self-image, bearing a sense of homogeneity.

This study is also academically significant because it highlights the structure of consumers’ self-brand connection by applying consumer needs satisfaction theory. Autonomy, relationship, and competence were set as components to identify the causal relationship between the satisfaction of consumer needs and self-brand connection. In this study, autonomy, as a factor of consumer need satisfaction, was not found to be significantly related to self-brand connection, as it does not create a sense of agreement or homogeneity with brands in terms of seeking personal freedom by watching influencers’ content. Furthermore, autonomy, as a consumer satisfaction need, is not a decisive factor in promoting intimacy or image consistency that consumers feel towards brands. However, relatedness and competence are considered important factors in achieving self-brand connection. Through the brands and services introduced by influencers, consumers have a strong tendency to maintain information, intimacy with others, and relationships. Consumers feel competent and capable while watching YouTube or other content broadcast online. The greater this tendency, the stronger the propensity to find a self-image connection with a brand.

As social media and the Internet have become increasingly prevalent, the emergence of social media celebrities (influencers) has become commonplace as a general marketing tool. Therefore, new online service development brands and advertisers are increasingly using social media. It has become essential for brands to verify the efficacy of influencers. The results of research on influencer marketing as a means of promoting brand and sales show interesting trends, proving the effectiveness of this means of promoting immediate sales, although this strategy is less effective in increasing post-contract growth. This approach helps to ensure that consumers interact with advertisers to obtain appropriate information, in addition to providing information on consumers’ purchases and word-of-mouth intentions.

This study was conducted at a time when the frequency of social discussions on sustainability related to the environment and humans was increasing. Considering the current market economy situation, the use of marketing communication through social media is increasing. The influence of influencers’ activity on social media, with respect to topics related to sustainability, and the influence of consumers’ self-concept of various sustainable behaviors were identified in this study. Whereas research related to social media and influencers has received considerable attention at the practical level, the resulting theoretical development is slow. The impact of social media on sustainability was examined in this study, and we attempted to elucidate the impact of influencers and consumers’ self-concepts by deviating from existing perspectives to explain sustainable behavior. This work can contribute to the understanding of the causal relationship between the variables of social distance and quasi-social interaction. The fact that this study established the influence relationship between social media and influencers in predicting the sustainable behavior of consumers contributes to the field of sustainable marketing.

7.3. Limitations

Despite the significance of this study, it is subject to the following limitations. We believe that social media influencers can encourage brand loyalty and ensure repeat purchases. This is believed to be a factor that affects consumers when selecting and evaluating brands. We suggest that subsequent studies are conducted considering these factors. The inability to select various products is a limitation of the present study. Furthermore, the characteristics of influencers should be further developed and investigated according to various perspectives. The present study was conducted with a focus on the characteristics of influencers, such as expertise, attractiveness, and reliability. However, in studies dealing with the persuasion effect of message sources, characteristics such as identification should also be considered. Future studies should consider such factors in an integrated manner to determine which factors have the most influence on word-of-mouth intention and the persuasiveness of marketing messages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; methodology, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; software, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; validation, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; formal analysis, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; investigation M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; resources, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; data curation, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; writing—review and editing, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; visualization, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; supervision, M.L., J.Y. and C.-H.J.; project administration, M.L, J.Y. and C.-H.J.; funding acquisition, M.L., J.Y. and C.-H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Because of the nature of this study, no formal approval of the Institutional Review Board of the local Ethics Committee was required. Nonetheless, all subjects were informed about the study and participation was on a fully voluntary basis. Participants were ensured of confidentiality and anonymity of the information associated with the surveys. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Argyris, Y.A.; Monu, K. Corporate use of social media: Technology affordance and external stakeholder relations. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2015, 25, 140–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.J.; Phua, J.; Lim, J.; Jun, H. Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. J. Interact. Advert. 2017, 17, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, S.; Ang, L.; Welling, R. Self-branding, “micro-celebrity” and the rise of social media influencers. Celebr. Stud. 2016, 8, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; Kerviler, G.; Moulard, J. Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram influencers: Theimpact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Muqaddam, A.; Ryu, E. Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalo, L.V.; Flavian, C.; IbanezSanchez, S. Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R. M&C Saatchi Acquires Two Influencer Agencies and Unveils New Talent Business; The Drum: Glasgow, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.thedrum.com/news/2018/06/27/mc-saatchi-acquirestwo-influencer-agencies-and-unveils-new-talent-business (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Neff, J. How to Succeed with Influencers: Brand Playbook; Ad Age. 2019. Available online: https://adage.com/article/cmo-strategy/succeed-influencers/316313 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Stafford, F.T.; Stafford, M.R.; Lawrence, L. Determining Uses and Gratifications for the Internet. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.; Larose, R.; Eastin, M.S.; Lin, C.A. Internet Gratifications and Internet Addiction: On the Uses and Abuses of New Media. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2004, 7, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharissi, Z.; Rubin, A.M. Predictors of Internet Use. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2000, 44, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Aisihaer, N.; Aihemaiti, A. Research on the impact of live streaming marketing by online influencers on consumer purchasing intentions. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1021256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Liu, C.; Shi, R. How Do Fresh Live Broadcast Impact Consumers’ Purchase Intention? Based on the SOR Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, I.; Andreu, L.; Curras-Perez, R. Effects of the intensity of use of social media on brand equity: An empirical study in a tourist destination. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 27, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schivinski, B.; Dabrowski, D. The effect of social media communication on consumer perceptions of brands. J. Mark. Commun. 2016, 22, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocamora, A. Fields of Fashion: Critical insights into Bourdieu’s sociology of culture. J. Consum. Cult. 2002, 2, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, J.; Schramm, H.; Schallhorn, C.; Wynistorf, S. Good guy vs bad guy: The influence of parasocial interactions with media characters on brand placement effects. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 720–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsuya, H. Influencer Marketing. Management Spirit; YDM: Seoul, Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boerman, S.C.; Willemsen, L.M.; Van Der Aa, E.P. This post is sponsored: Effects of sponsorship disclosure on persuasion knowledge and electronic word of mouth in the context of Facebook. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 38, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanesh, G.S.; Duthler, G. Relationship management through social media influencers: Effects of followers’ awareness of paid endorsement. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 1017–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Wang, R.; Chan-Olmsted, S. Factors affecting YouTube influencer marketing credibility: A heuristic-systematic model. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2018, 15, 188–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.; Swaminathan, V.; Brooks, G. Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Personal. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, H.T.; Sheldon, K.M.; Gable, S.L.; Roscoe, J.; Ryan, R.M. Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 6, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Park, C.W. The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L. Consumer experience and experiential marketing: A critical review. Rev. Mark. Res. 2013, 10, 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, C.; Spiller, N.; Noci, G. How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer? Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. You are what they eat: The influence of reference groups on consumers’ connections to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisjak, M.; Lee, A.Y.; Gardner, W.L. When a Threat to the Brand Is a Threat to the Self: The Importance of Brand Identification and Implicit Self-Esteem in Predicting Defensiveness. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Govorun, O.; Tanya, C. Effect of Self-awareness on Negative Affect Among Individuals with Discrepant Low Self-esteem. Self Identity 2012, 11, 3304–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.; Fischer, E. When conspicuous consumption becomes inconspicuous: The case of the migrant Hong Kong consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, G.E. Social class, social self-esteem, and conspicuous consumption. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mccracken, G. Who Is the Celebrity Endorser? Cultural Foundations of the Endorsement Process. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguen, N.T. The Influence of Celebrity Endorsement on Young Vietnamese Consumers’ Purchasing Intention. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 951–960. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Grolnick, W.S. Origins and pawns in the classroom: Self-report and projective assessments of individual differences in children’s perceptions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.D. The effects of personal control, competence, and extrinsic reward systems on intrinsic motivation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1978, 21, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.H.; Kuo, C.C.; Tan, M.J.E. The Cause and Effects of Word of Mouth from Consumer Intention and Behavior Perspectives: A SEM Model Approach. J. Econ. Soc. Thought 2017, 4, 212–231. [Google Scholar]

- Einwiller, S.; Fedorikhin, A.; Allison, J.; Kamins, M. Enough is enough! When identification no longer prevents negative corporate associations. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 34, 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.C.; Wang, C.Y.; Wu, L.W. Moderators of the negativity effect: Commitment, identification, and consumer sensitivity to corporate social performance. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeff, T.R. Consumption situations and the effects of brand image on consumer’s brand evaluations. Psychol. Mark. 1997, 14, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Qing, P.; Jin, Y.J.; Yu, J.; Dong, M.; Huang, L. Competition or spillover? Effects of platform-owner entry on provider commitment. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 144, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. The impact of celebrity spokespersons’ perceived image on consumers’ intention to purchase. J. Advert. Res. 1991, 31, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).