Augmenting Sustainable Fashion on Instagram

Abstract

:1. Introduction

SF includes the variety of means by which a fashion item or behaviour could be perceived to be more sustainable, including (but not limited to) environmental, social, slow fashion, reuse, recycling, cruelty-free and anti-consumption and production practices.

Instagram as a Platform for Augmenting Fashion

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Which Aspects of Sustainable Fashion Are Being Augmented through Instagram?

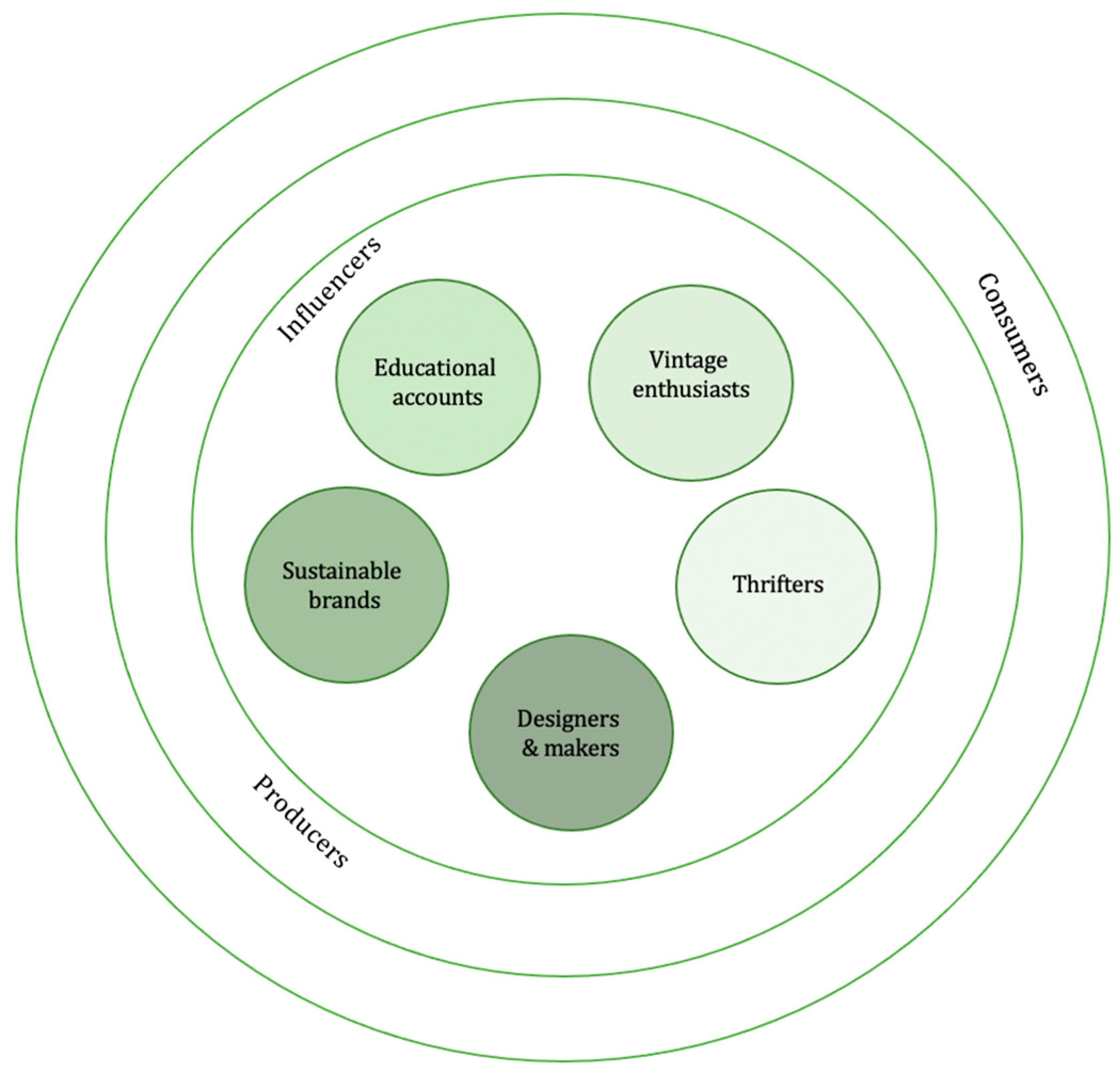

3.2. Who Are the Stakeholders Augmenting Sustainable Fashion on Instagram?

3.3. How Are These Stakeholders Augmenting Sustainable Fashion Using Instagram?

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- BBC. Fashion’s Dirty Secrets. 2018. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0bn6034 (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Greenpeace. The UK’s Fast Fashion Habit Is Getting Worse and It’s Destroying the Planet. 2022. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/news/the-uks-fast-fashion-habit-is-getting-worse-and-its-destroying-the-planet/?gclid=Cj0KCQjwkOqZBhDNARIsAACsbfIA7w59DKpgFYZplw6SL2UvRKTRw2kmY03npavHG0FOYdWQtWq1pzIaAkg-EALw_wcB (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Evans, S.; Peirson-Smith, A. The sustainability word challenge: Exploring consumer interpretations of frequently used words to promote sustainable fashion brand behaviours and imagery. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. 16 Things Everyone Should Know about Sustainable Fashion. Vogue. 2022. Available online: https://www.vogue.co.uk/fashion/article/sustainable-fashion (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Goldstone, P. The Best Online Vintage Clothing Stores to Shop More Sustainably This Autumn. Marie Claire. 2022. Available online: https://www.marieclaire.co.uk/fashion/best-online-vintage-stores-128388 (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Henninger, C.E. What is sustainable fashion? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairtrade International. Eight Years Later: From Rana Plaza to a Sustainable FASHION future. 2021. Available online: https://www.fairtrade.net/news/eight-years-later-from-rana-plaza-to-a-sustainable-fashion-future (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- British Fashion Council, Fashion and Environment. 2019. Available online: https://www.britishfashioncouncil.co.uk/uploads/files/1/NEW%20Fashion%20and%20Environment%20White%20Paper.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Fashion Revolution. About. 2022. Available online: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/about/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Hakovirta, M.; Denuwara, N. How COVID-19 redefines the concept of sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 12, 3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A. The Clean Clothes Campaign Launches “Pay Your Workers”. Fashion United. 2020. Available online: https://fashionunited.uk/news/business/the-clean-clothes-campaign-launches-pay-your-workers/2020092851099 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- McMaster, M.; Nettleton, C.; Tom, C.; Xu, B.; Cao, C.; Qiao, P. Risk management: Rethinking fashion supply chain management for multinational corporations in light of the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, P.R.S.; Kumar, A.; Choudhary, N.A.; Mangla, S.K. Modelling resilient fashion retail supply chain strategies to mitigate the COVID-19 impact. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelikánová, R.M.; Němečková, T.; MacGregor, R.K. CSR statements in international and Czech luxury fashion industry at the onset and during the COVID-19 pandemic—Slowing down the fast fashion business? Sustainability 2021, 13, 3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukendi, A.; Davies, I.; Glozer, S.; McDonagh, P. Sustainable fashion: Current and future research directions. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 54, 2873–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamkiewicz, J.; Kochańska, E.; Adamkiewicz, I. and Łukasik, R. Greenwashing and sustainable fashion industry. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 38, 100710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge Dictionary. Augment. 2022. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/augment (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Moatti, V.; Abecassis-Moedas, C. How Instagram Became the Natural Showcase for the Fashion World. Independent. 2018. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/fashion/features/instagram-fashion-industry-digital-technology-a8412156.html (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Hoffower, H. 4 Gen Z Fashion Trends Revived on TikTok in Response to the Pandemic. Insider. 2022. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/gen-z-fashion-trends-y2k-indie-sleaze-old-money-twee-2022-1?r=US&IR=T (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Ahmed, O. How Instagram transformed the fashion industry. i-D Magazine. 2021. Available online: https://i-d.vice.com/en/article/bj9nkz/how-instagram-transformed-the-fashion-industry (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Allen, C. Style surfing: Changing parameters of fashon communication—Where have they gone? In Proceedings of the 1st global conference: Fashion exploring critical issues, Mansfield College, Oxford, UK, 25–27 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rocamora, A. Personal fashion blogs: Screens and mirrors of digital self-portraits. Fash. Theory 2011, 15, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. Visibility labour: Engaging with influencers’ fashion brands and #OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media Int. Aust. 2016, 161, 86–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, P. Consumer attitude towards sustainability of fast fashion products in the UK. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocamora, A. Hypertextuality and remediation in the fashion media. J. Pract. 2011, 6, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, K. Just use what you have: Ethical fashion discourse and the feminisation of responsibility. Aust. Fem. Stud. 2019, 33, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoose, F.; Rosenbohm, S. Tension between autonomy and dependency: Insights into platform work of professional (video) bloggers. Work Glob. Econ. 2022, 2, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Johnson, B.K. Are they being authentic? The effects of self-disclosure and message sidedness on sponsored post effectiveness. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 30–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K. Shoppers take to TikTok to complain about Molly-Mae Hague’s PrettyLittleThing Line. Independent. 2021. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/fashion/prettylittlething-molly-mae-hague-tiktok-b1914235.html (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Douglass, R. eBay’s Love Island Collaboration Causes Surge in Pre-Loved Popularity. Fashion United. 2022. Available online: https://fashionunited.uk/news/culture/ebay-s-love-island-collaboration-causes-surge-in-pre-loved-popularity/2022071164035 (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Marroncelli, R. Love Island ditches fast fashion: How reality celebrities influence young shoppers’ habits. The Conversation. 2022. Available online: https://theconversation.com/love-island-ditches-fast-fashion-how-reality-celebrities-influence-young-shoppers-habits-183771 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- McKeown, C.; Shearer, L. Taking sustainable fashion mainstream: Social media and the institutional celebrity entrepreneur. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.F.; Alanadoly, A.B. Personality traits and social media as drivers of word-of-mouth towards sustainable fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, D.S.; Bakhshian, S.; Eike, R. Engaging consumers with sustainable fashion on Instagram. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 25, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanesi, M.; Kyrdoda, Y.; Runfola, A. How do you depict sustainability? An analysis of images posted on Instagram by sustainable fashion companies. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcella-Hood, M.; Marcella, R. Purposive and non-purposive information behaviour on Instagram. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2022. online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.M.; Corbin, J. Grounded Theory in Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Instagram. #SustainableFashion. 2022. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/sustainablefashion/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Barthes, R. Image/Music/Text; Editions du Seuil: Paris, France, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Patagonia. Earth Is Now Our Only Stakeholder. 2022. Available online: https://eu.patagonia.com/gb/en/ownership/ (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Textile Consult. Why Donating Your Unwanted Clothes Isn’t Always the Sustainable Solution. 2019. Available online: https://www.textileconsult.co.uk/2019/04/12/why-donating-your-unwanted-clothes-isnt-always-the-sustainable-solution/ (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Ehlers, K. Micro-Influencers: When Smaller Is Better. Forbes. 2021. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2021/06/02/micro-influencers-when-smaller-is-better/?sh=109846b4539b (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Lim, H.; Childs, M.L. Brand Storytelling on Instagram: How Do Pictures Travel to Millennial Consumers’ Minds? In International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings; Iowa State University Digital Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2016; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, R. The humanisation of media? Social media and reformation of communication. Commun. Res. Pract. 2015, 1, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra-Gant, M. Pictures or it Didn’t happen: Photo-nostalgia, iPhoneography and the representation of everyday life. Photogr. Cult. 2016, 9, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, H.; Cook, J. Formations of belonging in Australia: The role of nostalgia in experiences of time and place. Popul. Space Place 2019, 25, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassinger, C.; Thelander, Å. Co-creation constrained: Exploring gazes of the destination on Instagram. In The Routledge Companion to Media and Tourism; Månsson, M., Buchmann, A., Cassinger, C., Eskilsson, L., Eds.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kádár, B.; Klaniczay, J. Branding Built Heritage through Cultural Urban Festivals: An Instagram Analysis Related to Sustainable Co-Creation, in Budapest. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. Fashion Ethics; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bedat, M. Unravelled: The Life and Death of a Garment; Penguin: New York City, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Denoted meaning | Barthes describes this as the first level of meaning—the literal meaning that is immediately obvious to a viewer |

| Connoted meaning | Barthes describes this as the second level of meaning—suggested or symbolic meanings including ideas and feelings |

| Contextual meaning | Contextual parameters within which the post can be interpreted and understood, i.e., Instagram and sustainable fashion |

| RQ1: Which aspects of sustainable fashion are being augmented through Instagram? | RQ2: Who are the stakeholders augmenting sustainable fashion on Instagram? | RQ3: How are these stakeholders augmenting sustainable fashion using Instagram? |

| The imperative | Educational accounts | Consistency |

| News | Vintage enthusiasts | Story telling |

| Sustainable brands and products | Thrifters and second-hand consumers | Nostalgia |

| Vintage fashion | Sustainable designers and makers | Co-creation |

| Upcycling | Sustainable brands | Inclusivity |

| Sub-genres of fashion | Positivity |

| RQ1: Which aspects of sustainable fashion are being augmented through Instagram? | |

| The imperative | Denoted: A photograph of a garment factory with text overlay stating “reasons why [named fast fashion brand] is the devil ”Connoted: This photograph connotes fast fashion’s association with unethical supply chains, poor working conditions, unfair pay, and calls this out as unacceptable. Positioning this brand as “the devil” connotes the idea that they represent the very worst example of all that is wrong with fast fashion. Context: The named brand is a global online retailer that is recognised as an extreme example of fast fashion and cheap clothing production. The post is shared by an informational account and is designed to educate followers about unethical business practice and presumably encourage consumers to boycott fast fashion. The combination of photography and text aligns visually with other content produced by this account, where a consistent font style is used. |

| News | Denoted: A photograph of a man sitting at a desk, pen poised and looking directly at the camera/audience. The words “breaking news: Patagonia founder gives away company to fight climate change” appear as text overlay. Connoted: This photograph connotes the reproduction of a current news story. The “breaking news” headline is attention grabbing and the man’s pose and gaze suggest action and invite the viewer to engage. Whilst the background setting of the image is homely and relaxed, the man looks serious. The named brand, individual founder, and headline are the signifiers in this post. Context: The brand is known and recognised in this context as a sustainable fashion brand [35]. The caption reveals the story around its founder gifting his company to the Earth, in what could be considered an act of generous philanthropy and a rejection of capitalist motivations and aspirations for the business. This story had been shared numerous times across the data set during the period of data collection (by individual users, sustainable brands, etc.), but in this particular example is being shared by a sustainable lifestyle account that describes itself as “the home of sustainability”. Its purpose appears to be to inform its followers on how to live more sustainably across a variety of topics from fashion to food. Its motivation towards sharing this story is likely to be to further engage followers on the topic of sustainability, but also to establish itself as a key source of current news. The account applies a consistent aesthetic across its posts, which are not exclusively fashion-related but always relate to sustainable topics. Much of the content offers specific tips and advice. |

| Sustainable brands and products | Denoted: A photograph of a fashion garment modelled by a young woman. Connoted: The garment and model are at the forefront of the image and can be considered the main signifiers. The background is an indoor winter-garden setting with visible cacti and foliage. The model poses in a way that draws attention to the garment. She looks directly at the camera, engaging the viewer. This could be considered an aspirational image in that the styling of the garment and model appears intentional and formal. Although the image alone connotes fashion more so than any obvious message about sustainability, the background foliage combined with the use of sustainable fashion hashtags reminds the viewer of earth and nature as driving factors of sustainability. Context: The denoted brand describes itself specifically as “slow fashion” and is based in Madrid, Spain. The brand produces and sells new garments in a particular and consistent style that does not appear to be trend-led, e.g., ethnic influences are referenced and cited, such as a Japanese kimono-style design. The account is curated using a consistent design aesthetic, alternating between fashion photographs and interesting, attractive locations. The prominence of physical place aligns with the idea of slow fashion. |

| Vintage fashion | Denoted: A still-life photograph denoting five long women’s dresses hanging on a rail underneath a shelf with a plate and vases of dried flowers. Connoted: The image represents an “edit” (i.e., curated selection) of five dresses, which have been selected from a wider group of garments. The dresses are positioned in a pattern of complementary colours, prints, and fabrics in earthy natural tones—green, brown and cream. The dresses coordinate in that they are all of a similar style and length. The post is shared by a vintage retailer who presumably is attempting to engage customers. The accompanying post is long and personal, telling/reminding followers that this is part of a regular “edit” and encouraging them to engage with future upcoming content. More information about the dresses is indicated using hashtags, e.g., #70sstyle, #70sdress, and #prairiedress. The garments as a set are the signifiers and this is reinforced by the accompanying captions. The positioning of the shelf and objects is intentional and in keeping with the 1970s, e.g., dried grass. Context: The account is a vintage retailer that specialises in women’s dresses and produces consistent content, e.g., weekly edits and product and lifestyle posts. A similar colour scheme is used in posts and many of the images are styled carefully in ways similar to the current example. |

| Upcycling | Denoted: A brown and beige hooded top with a duck motif is photographed on a hanger, against a background of a weathered wooden fence. Connoted: The garment is constructed in a patchwork design, which is suggestive of the fact it is handmade by the poster. The garment is the signifier in the image as there are no other objects visible and the background is unremarkable, perhaps adding further to the homemade, casual tone of the post. There is no attempt to complement or distract from the garment with additional styling elements. The photograph is part of a carousel of images, where additional photographs reveal further details by showing the garment from different angles. The caption provides further information about the materials used and sizing, alerting the viewer to the fact that it can be purchased. Context: The post is shared by a designer who makes clothing using vintage material, e.g., this particular piece was made using fabric from an old beach towel, a textile which is used in a number of other designs that are shared by the user. Designs and posts follow a consistent style and the particular styles and patterns that are used have a familiar and retro/nostalgic feel. |

| Sub-genres of fashion | Denoted: A photograph of children’s clothing styled into an entire outfit, and laid out flat on a surface with a text overlay naming the business/store. Connoted: The garment and store are the key signifiers within this image. The clothing is colourful and a selection of prints are positioned together, i.e., hedgehog, rainbow, and hearts—all of which individually have connotations of nature, kindness, love, compassion, etc. The address of the store is included, which promotes the call to action to visit. The garments are new but are advertised as using organic cotton as a more environmentally friendly material. Context: This is a promotional image, which presumably aims to attract customers, encouraging people to visit the shop and buy the products. It is in keeping with other posts on the feed, all of which feature similar styles of children’s clothing. The feed alternates between close-up shots, such as the current example, and further away pictures of the store. |

| RQ2: Who are the stakeholders augmenting sustainable fashion on Instagram? | |

| Educational accounts | Denoted: A graphic image containing an illustrated squirrel on a yellow background with the words “progress is making gradual steps forward” and a logo. Connoted: This image connotes the idea of progress in relation to sustainable fashion. The squirrel represents the significance of small but continuous effort and work, and the sunshine yellow background suggests warmth and positivity. The logo for this account appears on the image suggesting ownership over the creative and intellectual output, i.e., the illustration and the message. The squirrel illustration is retro in style, connoting nostalgia but also nature and the environment. Context: The account comprises a consistent set of imagery that always contains typography and usually retro/vintage illustrations in an array of vibrant colours. This account could be described as educational/informational, with the apparent aim of educating followers about issues of sustainability and ethics relating to fashion. The account appears professional in its approach and promotes a podcast on this same subject. The messages are proactive but often very specific and targeted at particular audiences. The messages are inclusive, using the words “we”, “us”, etc. |

| Vintage enthusiasts | Denoted: A photograph of a woman sitting on a garden bench looking at the camera. Connoted: The woman is wearing an interesting and unique ensemble (turtle-neck jumper, frilly prairie-style dress, suit jacket, lace-up ankle boots, visible frilly socks, bowler hat). She is further adorned with beaded necklaces, large earrings, broaches and badges, and wears large round glasses. The style is recognisable as “maximalist” and eclectic, i.e., with lots of layers, prints/textures and accessories teamed together in a way that looks thrown together but might actually be carefully curated. Her legs are crossed and her hands are clasped in what could be described as a dignified pose. The woman is the key signifier but her style is a focal aspect on the post as her whole outfit is visible and details are further revealed in a carousel of additional images, with detailed close up shots of the clothing from a variety of angles. More information about the vintage garments and 1970s style is revealed in the caption, including the fact that she adapted/upcycled parts of this herself. The post is long and written in a personal manner, suggesting her and her followers are on a journey together and that she has shared a lot with them in the past. Additional hashtags, such as #sewoverageism and #styleatanyage, reveal further personal details about the wearer. Although she is alone in the photograph, she is not alone in real life as someone is taking her photo. Context: This poster can be described as a vintage enthusiast/upcycler who uses the platform as a personal style journal. Her posts almost always involve a picture of herself and this post represents a signature style of photography where she is sitting on an iron bench in what appears to be a cobbled yard with some greenery spilling from pots in the background. Her personal style is consistent across her feed but she is often also pictured out and about in indoor and outdoor settings, often with historic aspects, e.g., cobbles, walls, antiques, etc. Someone is taking her photo but they do not appear on the feed. |

| Thrifters and second-hand consumers | Denoted: A photograph of a woman sitting on a doorstep posing and looking down at her clothing. Connoted: The woman’s pose connotes clothing as the main signifier. The top of her face is not pictured in the image. The outfit is bold in colour but casual, consisting of light-wash jeans, a bright-red top and black-patent boots. The caption further highlights the outfit as a focal point of the post, revealing the wearer’s love of second-hand clothing and her thrill/enjoyment when shopping for this. Context: The poster’s profile is a documentary of her personal style and most of the content could be described as fashion-related, with some lifestyle aspects. She describes herself as a “charity shop fiend”, which emphasises this user’s sustained enthusiasm. |

| Sustainable designers and makers | Denoted: A photograph of a man’s torso wearing a hoody picturing a popular cartoon character. Connoted: The hoody is the focal point of the image and the obvious signifier. The wearer’s head is not visible in the photograph. The cartoon emblem is retro in style, which will have nostalgic resonance as well as current appeal to audiences. The garment appears handmade and has been repurposed, although there is no information about the origins of the original material that was used to construct it. The caption gives more information about sizing and the call to action is to “grab it tomorrow at 8pm”. This is all suggestive of a loyal audience who are being reminded of this information rather than being told for the first time. Context: The purpose of the account appears to be business orientated but personalised to an individual rather than a company or brand identity. The post alludes to a weekly “drop” of new items, which is a recognised scarcity marketing technique within the fashion industry, in particular amongst niche streetwear brands. The profile consists entirely of garment posts, all of which are upcycled and most of which include vintage/retro cartoons. These appear gender neutral but are often advertised using a men’s sizing classification. Sometimes the garments are photographed in flat lay style format but mostly they are photographed on someone, and the face of the wearer is almost never shown. Occasionally the individual poster is pictured on the feed. |

| Sustainable brands | Denoted: A photograph of a bag. Connoted: The photograph is high-resolution and camera quality, which suggests a professional approach. The product is a utilitarian style bag in mint-green colour, shown against a corresponding (rather than contrasting) background; the styling of the image suggests that design software has been used to create the background colour and, therefore, the photo has likely been taken in a studio. The bag is the signifier as there are no other objects or distractions within the photo. The product is branded with the company’s logo, which is clearly visible and stands out as a grey patch on the bag. The caption is descriptive and highlights further product attributes, particularly relating to sustainability using hashtags including #recycledfashion and #sustainablenewiconicbag. Context: The profile is that of a brand, which specialises in one concept product in a variety of colours. The profile is colourful (e.g., pinks, greens, blues, yellows, oranges) and engaging, using a combination of graphics and illustrations. The profile feed comprises close-up product shots against plain backgrounds and more vibrant shots with lifestyle details including people and illustrations. The purpose of the account appears to be mostly promotional, designed to attract new customers and engage with existing customers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marcella-Hood, M. Augmenting Sustainable Fashion on Instagram. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043609

Marcella-Hood M. Augmenting Sustainable Fashion on Instagram. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043609

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarcella-Hood, Madeleine. 2023. "Augmenting Sustainable Fashion on Instagram" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043609

APA StyleMarcella-Hood, M. (2023). Augmenting Sustainable Fashion on Instagram. Sustainability, 15(4), 3609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043609