Identifying How E-Service Quality Affects Perceived Usefulness of Online Reviews in Post-COVID-19 Context: A Sustainable Food Consumption Behavior Paradigm

Abstract

1. Introduction

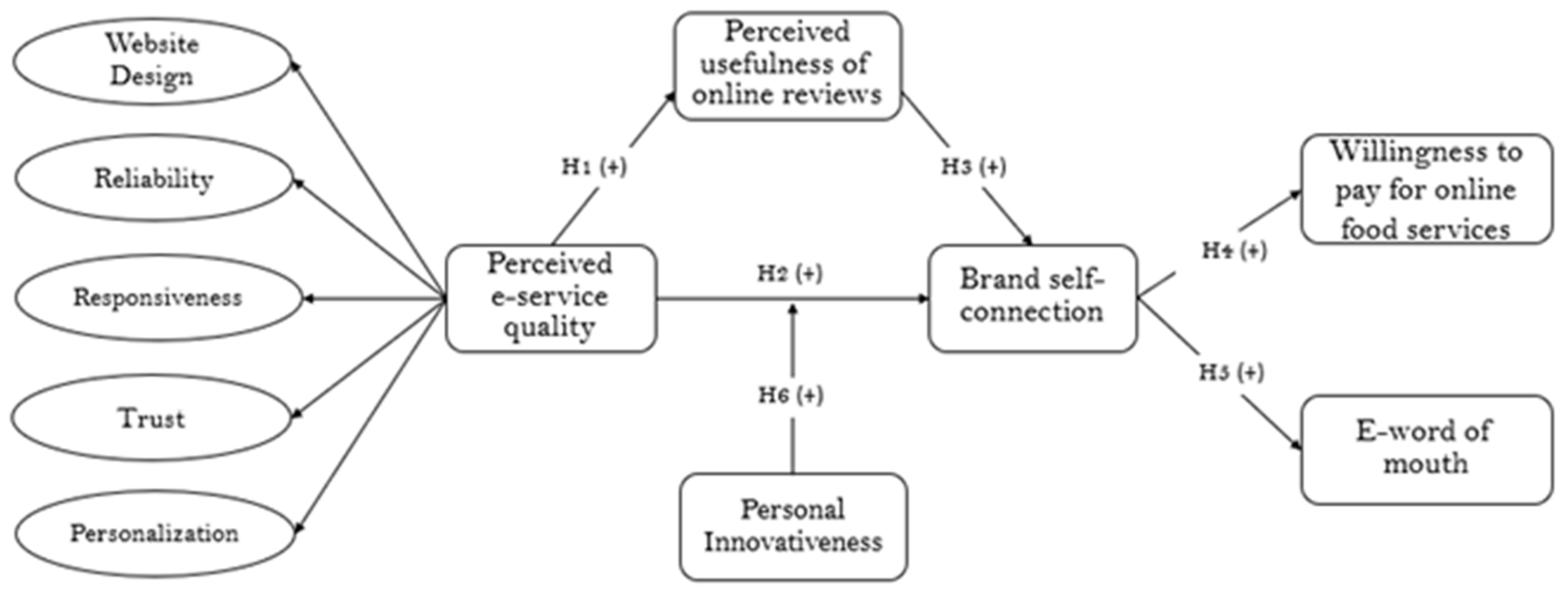

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Quality of Online Food Services in the Post-COVID-19 Period

2.2. Perceived E-Service Quality and Perceived Usefulness of Online Reviews

2.3. Perceived E-Service Quality and Self-Brand Connection

2.4. Perceived Usefulness of Online Reviews and Self-Brand Connection

2.5. Self-Brand Connection and E-Word of Mouth

2.6. Self-Brand Connection and Willingness to Pay More

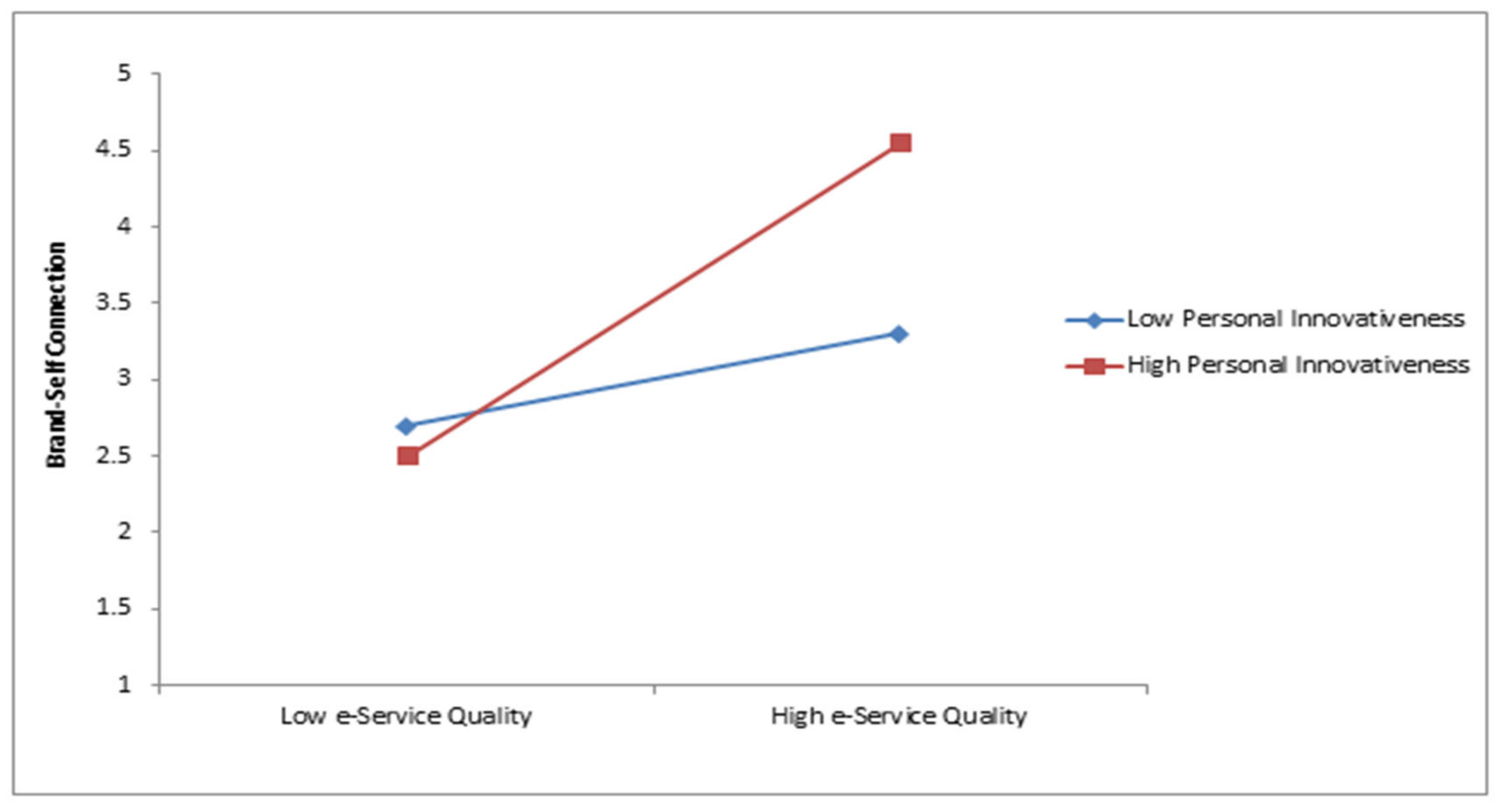

2.7. The Moderating Role of Personal Innovativeness

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures and Validation

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Validation

4.2. Reliability Analysis

4.3. Multicollinearity

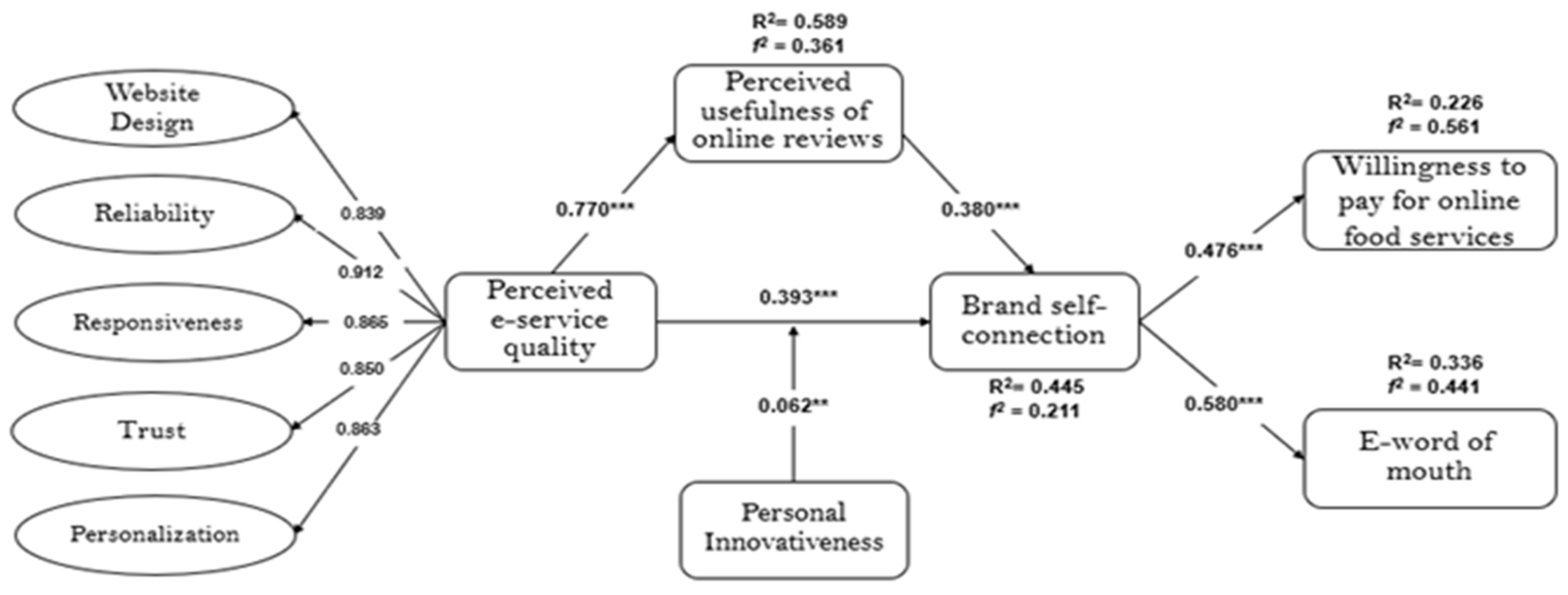

4.4. Structural Model and Hypothesis Outcomes

4.5. Second-Order Construct

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implication

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guerreiro, J.; Rita, P. How to predict explicit recommendations in online reviews using text mining and sentiment analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D. Unraveling the interplay of review depth, review breadth, and review language style on review usefulness and review adoption. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Choi, H.H.; Choi, E.K.C.; Joung, H.W.D. Factors affecting customer intention to use online food delivery services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Park, S. What makes a useful online review? Implication for travel product websites. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R. Customer engagement and online reviews. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khalid, N.; Javed, H.M.U.; Islam, D.M.Z. Consumer Adoption of Online Food Delivery Ordering (OFDO) Services in Pakistan: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Situation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, X. Comparative study of deep learning models for analyzing online restaurant reviews in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Mirosa, M.; Bremer, P. Review of Online Food Delivery Platforms and their Impacts on Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrolia, S.; Alagarsamy, S.; Solaikutty, V.M. Customers response to online food delivery services during COVID-19 outbreak using binary logistic regression. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 45, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunden, N.; Morosan, C.; DeFranco, A. Consumers’ intentions to use online food delivery systems in the USA. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1325–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Ø.; Hansen, K.V. Consumer values among restaurant customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhi, G.e.R.; Mohamadali, N.A. Antecedents of Overall E-service Quality and Brand Attachment in the Banking Industry. SEISENSE J. Manag. 2020, 3, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, M.Á.; Monferrer-Tirado, D.; Estrada-Guillén, M. Consequences of customer engagement and customer self-brand connection. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventre, I.; Kolbe, D. The Impact of Perceived Usefulness of Online Reviews, Trust and Perceived Risk on Online Purchase Intention in Emerging Markets: A Mexican Perspective. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020, 32, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Shin, D.H.; Cohen, J. Understanding trust and perceived usefulness in the consumer acceptance of an e-service: A longitudinal investigation. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 36, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubaishat, A. Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of electronic health records among nurses: Application of Technology Acceptance Model. Inform. Heal. Soc. Care 2018, 43, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Ahmad, M. Relating consumers’ information and willingness to buy electric vehicles: Does personality matter? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 100, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Ahmad, M.; Mohsin, M.; Dagar, V.; Hao, Y. Prioritizing and overcoming biomass energy barriers: Application of AHP and G-TOPSIS approaches. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 177, 121524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lari, L.A.D.A.; Iyanna, S.; Jabeen, F. Islamic and Muslim tourism: Service quality and theme parks in the UAE. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casidy, R. Linking Brand Orientation with Service Quality, Satisfaction, and Positive Word-of-Mouth: Evidence from the Higher Education Sector. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2014, 26, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. The acceptance of augmented reality tour app for promoting film-induced tourism: The effect of celebrity involvement and personal innovativeness. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2021, 12, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, W. Investigating motivated consumer innovativeness in the context of drone food delivery services. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, J.; Djakasaputra, A.; Pramono, R.; Bernarto, I. Observational Learning and Word of Mouth Against Consumer Online Purchase Decision during the Pandemic COVID-19. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 751–758. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Chi, X.; Baek, H.; Lee, K.S. Impact of environmental CSR, service quality, emotional attachment, and price perception on word-of-mouth for full-service airlines. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xie, K.L.; Zhang, Z. The effects of consumer experience and disconfirmation on the timing of online review: Field evidence from the restaurant business. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.Y.; Jackson, V.P. The Effect of E-SERVQUAL on e-Loyalty for Apparel Online Shopping. J. Glob. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 19, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J. An analysis of the e-service literature: Towards a research agenda. Internet Res. 2006, 16, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Ali, M.H.; Tan, K.H.; Sjahroeddin, F.; Kusdibyo, L. Loyalty toward online food delivery service: The role of e-service quality and food quality. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigatto, G.; Machado, J.G.d.C.F.; Negreti, A.d.S.; Machado, L.M. Have you chosen your request? Analysis of online food delivery companies in Brazil. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.; Papagiannidis, S.; Alamanos, E.; Bourlakis, M. The role of brand attachment strength in higher education. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3049–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Gregor, S.; Lin, A. Biophilia and biophobia in website design: Improving internet information dissemination. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Fatma, M.; Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. Brand engagement and experience in online services. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathi, P.; Abu-Shanab, E.A. Customer Satisfaction with Online Food Ordering Portals in Qatar. Int. J. E-Serv. Mob. Appl. 2020, 12, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. You Are What They Eat: The Influence of Reference Groups on Consumers’ Connections to Brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floh, A.; Koller, M.; Zauner, A. Taking a deeper look at online reviews: The asymmetric effect of valence intensity on shopping behaviour. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 646–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, V.; Page, K.L.; Gürhan-Canli, Z. “My” brand or “our” brand: The effects of brand relationship dimensions and self-construal on brand evaluations. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuskej, U.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K. The role of consumer-brand identification in building brand relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.; Mattila, A.S. The Effect of Self–Brand Connection and Self-Construal on Brand Lovers’ Word of Mouth (WOM). Cornell Hosp. Q. 2015, 56, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, L.M. Brand loyalty: Exploring self-brand connection and brand experience. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. What drives customers’ willingness to pay price premiums for luxury gastronomic experiences at michelin-starred restaurants? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbedweihy, A.M.; Jayawardhena, C.; Elsharnouby, M.H.; Elsharnouby, T.H. Customer relationship building: The role of brand attractiveness and consumer-brand identification. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2901–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Priester, J.R.; MacInnis, D.J. The connection-prominence attachment: (CPAM): A conceptual and methodological exploration of brand attachment. In Handbook of Brand Relationships; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009; pp. 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, R.; Srivastava, M. Adoption readiness, personal innovativeness, perceived risk and usage intention across customer groups for mobile payment services in India. Internet Res. 2014, 24, 369–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.D.; Yi, M.Y.; Park, J.S. An empirical test of three mediation models for the relationship between personal innovativeness and user acceptance of technology. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianlin, W.; Qi, D. Moderating effect of personal innovativeness in the model for e-store loyalty. In Proceedings of the International Conference on E-Business and E-Government, ICEE, Guangzhou, China, 7–9 May 2010; pp. 2065–2068. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, N.; Yoo, Y.; Heo, T.Y. Moderating effect of personal innovativeness on mobile-RFID services: Based on Warshaw’s purchase intention model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2009, 76, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Akhtar, N.; Ahmad, M.; Shahzad, F.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Wu, H.; Yang, C. Assessing public willingness to wear face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic: Fresh insights from the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanveer, A.; Zeng, S.; Irfan, M. Do Perceived Risk, Perception of Self-Efficacy, and Openness to Technology Matter for Solar PV Adoption? An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Energies 2021, 14, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.H.; Zhongfu, T.; Ahmad, B.; Irfan, M.; Razzaq, A.; Ameer, W. Influencing factors of consumers’ buying intention of solar energy: A structural equation modeling approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobanoglu, C.; Cobanoglu, N. The effect of incentives in web surveys: Application and ethical considerations. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.G.; Lin, H.F. Customer perceptions of e-service quality in online shopping. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2005, 33, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Macinnis, D.J.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Iacobucci, D. Brand Attachment and Brand Attitude Strength: Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation of Two Critical Brand Equity Drivers. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Qu, H.; Kim, Y.S. A study of the impact of personal innovativeness on online travel shopping behavior—A case study of Korean travelers. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Cantallops, A.; Ramon-Cardona, J.; Salvi, F. The impact of positive emotional experiences on eWOM generation and loyalty. Spanish J. Mark. ESIC 2018, 22, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Irfan, M.; Mukeshimana, M.C.; Rehman, A.; Jabeen, G.; Li, H. Modeling heterogeneous dynamic interactions among energy investment, SO2 emissions and economic performance in regional China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 2730–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobuervable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.K.-K. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Strupeit, L.; Palm, A. Overcoming barriers to renewable energy diffusion: Business models for customer-sited solar photovoltaics in Japan, Germany and the United States. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.E. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 490. [Google Scholar]

- Lucianetti, L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Gunasekaran, A.; Latan, H. Contingency factors and complementary effects of adopting advanced manufacturing tools and managerial practices: Effects on organizational measurement systems and firms’ performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 200, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Nicolau, J.L.; Tang, L. The Impact of Restaurant Innovativeness on Consumer Loyalty: The Mediating Role of Perceived Quality. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 1464–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satti, Z.W.; Babar, S.F.; Parveen, S.; Abrar, K.; Shabbir, A. Innovations for potential entrepreneurs in service quality and customer loyalty in the hospitality industry. Asia Pacific J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 14, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.F.; Lee, T.Z. The influence of trust and usefulness on customer perceptions of e-service quality. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2011, 39, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.C.; Chou, P.Y.; Wen-Chien, L. Evaluation of satisfaction and repurchase intention in online food group-buying, using Taiwan as an example. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hwang, J. Who is an evangelist? Food tourists’ positive and negative eWOM behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 34, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.M.; Lee, S.; Jeong, M. Perceived corporate social responsibility and customers’ behaviors in the ridesharing service industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satti, Z.W.; Babar, S.F.; Ahmad, H.M. Exploring mediating role of service quality in the association between sensory marketing and customer satisfaction. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 32, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Lin, S.; Li, J. Public perceptions and acceptance of nuclear energy in China: The role of public knowledge, perceived benefit, perceived risk and public engagement. Energy Policy 2019, 126, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 287 | 67.8 |

| Female | 136 | 32.1 |

| Age | ||

| 20 years or younger | 79 | 18.6 |

| 21–30 | 172 | 40.6 |

| 31–40 | 89 | 21.0 |

| 41–50 | 52 | 12.2 |

| 51–60 | 31 | 7.32 |

| Education | ||

| High school | 15 | 3.5 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 210 | 49.6 |

| Master | 154 | 36.4 |

| PhD | 44 | 10.4 |

| Income | ||

| <5000 | 6 | 1.4 |

| 5001–8000 | 121 | 28.6 |

| 8001–10,000 | 161 | 38.1 |

| 10,001–13,000 | 79 | 18.7 |

| 13,001–15,000 | 46 | 10.9 |

| Above 15,000 | 10 | 2.4 |

| Profession | ||

| Teacher | 101 | 23.9 |

| Businessmen | 111 | 26.2 |

| Government Job | 59 | 13.9 |

| Proprietor | 144 | 34.0 |

| Doctor | 8 | 1.9 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSC | 0.808 | |||||

| PRI | 0.180 | 0.857 | ||||

| PUO | 0.689 | 0.070 | 0.777 | |||

| WPO | 0.476 | 0.081 | 0.556 | 0.879 | ||

| ESQ | 0.692 | 0.069 | 0.764 | 0.575 | 0.712 | |

| e-WOM | 0.580 | 0.050 | 0.625 | 0.765 | 0.664 | 0.803 |

| Constructs | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived e-service quality | 0.925 | 0.935 | 0.507 |

| Brand self- connection | 0.733 | 0.849 | 0.652 |

| Perceived usefulness | 0.782 | 0.859 | 0.604 |

| Personal innovativeness | 0.748 | 0.846 | 0.735 |

| e-word of mouth | 0.816 | 0.879 | 0.644 |

| Willingness to pay more | 0.852 | 0.911 | 0.772 |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Website design | WEBD1 | 0.836 | 2.218 |

| WEBD2 | 0.886 | 2.775 | |

| WEBD3 | 0.819 | 2.318 | |

| Reliability | RLB1 | 0.788 | 2.282 |

| RLB2 | 0.816 | 2.234 | |

| RLB3 | 0.821 | 2.646 | |

| RLB4 * | - | - | |

| Responsiveness | RSP1 | 0.807 | 2.540 |

| RSP2 | 0.875 | 2.021 | |

| RSP3 | 0.762 | 1.923 | |

| Trust | TRST1 | 0.903 | 1.184 |

| TRST2 | 0.870 | 2.187 | |

| Personalization | PLSN1 | 0.807 | 2.690 |

| PLSN2 | 0.875 | 2.327 | |

| PLSN3 | 0.762 | 2.454 | |

| Brand self-connection | BSC1 | 0.768 | 1.415 |

| BSC2 | 0.814 | 1.480 | |

| BSC3 | 0.839 | 1.647 | |

| BSC4 * | - | - | |

| Perceived usefulness of online reviews | PUO1 | 0.746 | 1.500 |

| PUO2 | 0.783 | 1.654 | |

| PUO3 | 0.859 | 1.845 | |

| PUO4 | 0.713 | 1.488 | |

| Personal innovativeness | PI1 | 0.821 | 1.225 |

| PI2 | 0.866 | 1.458 | |

| PI3 | 0.907 | 1.393 | |

| PI4 | 0.803 | 1.369 | |

| E-word of mouth | eWOM1 | 0.815 | 1.836 |

| eWOM2 | 0.815 | 1.732 | |

| eWOM3 | 0.772 | 1.594 | |

| eWOM4 | - | - | |

| eWOM5 | 0.807 | 1.639 | |

| Willingness to pay | WPO1 | 0.905 | 2.446 |

| WPO2 | 0.875 | 2.201 | |

| WPO3 | 0.856 | 1.870 |

| Hypotheses | Beta | p Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: ESQ → PUO | 0.770 *** | 0.01 | Accepted |

| H2: ESQ → BSC | 0.393 *** | 0.01 | Accepted |

| H3: PUO → BSC | 0.380 *** | 0.01 | Accepted |

| H4: BSC → WPO | 0.476 *** | 0.01 | Accepted |

| H5: BSC → e-WOM | 0. 580 *** | 0.01 | Accepted |

| H6: ESQ × PRI → BSC | 0.062 ** | 0.05 | Accepted |

| Second-Order Construct | First-Order Constructs | Weights | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESQ | Web site design | 0.839 *** | 0.000 |

| ESQ | Reliability | 0.912 *** | 0.000 |

| ESQ | Responsiveness | 0.865 *** | 0.000 |

| ESQ | Trust | 0.850 *** | 0.000 |

| ESQ | Personalization | 0.863 *** | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xin, Y.; Irfan, M.; Ahmad, B.; Ali, M.; Xia, L. Identifying How E-Service Quality Affects Perceived Usefulness of Online Reviews in Post-COVID-19 Context: A Sustainable Food Consumption Behavior Paradigm. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021513

Xin Y, Irfan M, Ahmad B, Ali M, Xia L. Identifying How E-Service Quality Affects Perceived Usefulness of Online Reviews in Post-COVID-19 Context: A Sustainable Food Consumption Behavior Paradigm. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021513

Chicago/Turabian StyleXin, Yongrong, Muhammad Irfan, Bilal Ahmad, Madad Ali, and Lanqi Xia. 2023. "Identifying How E-Service Quality Affects Perceived Usefulness of Online Reviews in Post-COVID-19 Context: A Sustainable Food Consumption Behavior Paradigm" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021513

APA StyleXin, Y., Irfan, M., Ahmad, B., Ali, M., & Xia, L. (2023). Identifying How E-Service Quality Affects Perceived Usefulness of Online Reviews in Post-COVID-19 Context: A Sustainable Food Consumption Behavior Paradigm. Sustainability, 15(2), 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021513