Abstract

Substantial evidence shows that the current level of children’s physical activity (PA) is insufficient. Schools along with academic lessons can offer an effective avenue to increase children’s physical activity and decrease sedentary time. Teacher training in movement integration (MI) has been emphasized as an important strategy in facilitating less sedentary and more physically active lessons. The aim of this study was to explore the design process for developing a teacher training module for MI and its implementation within the comprehensive, school-based, physical activity program. Flexible co-creation methods with teachers were applied. Process evaluation was conducted through individual feedback surveys, observations in schools, evaluating the teacher’s MI mapping timetable, group feedback, and a follow-up study. The two-day module, a practical and flexible approach, ready-to-use resources, allocated time and autonomy for practice, communication with other teachers, and a whole school approach aligned with teachers’ needs are identified as key elements. A follow-up study after the training showed significant changes in teachers’ practices regarding the use of MI in the classroom. The study offers important insights into the design process and its successes and failures. The lessons learnt, a final model of designed seminars, and a toolbox of materials are presented.

1. Introduction

Substantial evidence shows that physical activity (PA) is fundamental for children’s health and development [1]. Worldwide, overall PA has rapidly declined and sedentary behavior has increased [2,3,4], and the pandemic situation over the last few years has had additional negative effects on children’s PA levels [5,6,7]. Population-based studies indicate that one-third of school-aged children achieve the WHO recommended 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA) per day to accrue health benefits [8]. In Estonia, only one-fourth of school children meet the recommendation to spend at least 60 min in MVPA a day [9]. It is essential to provide children and adolescents various opportunities for physical activity (PA) throughout their childhood, including in the formal educational system [10]. Although schools are potentially powerful agents to support changes to children’s PA levels [11], PA promotion is not an inherent part of their existing agenda and PA in schools is often sparse and restricted to physical education lessons [12].

Therefore, there is the need to prioritize the development of comprehensive, school-level interventions to support PA opportunities throughout the school day [13]. It has been advised that students should accumulate a minimum of 30 min of MVPA at school [14], which is roughly 50% of their daily PA requirements. However, it has also been reported that children spend most of the school day seated and the estimated sedentary time in school is ca. 76% in grades 1–3 and up to 87% in grades 7–9 [15].

Studies indicate that PA has a positive effect on children’s academic behavior [16,17,18]. There are several ways to increase children’s PA during the school day (e.g., active breaks, physical education classes, PA before and after school [19]). One way to increase children’s PA that has recently received more attention is to integrate PA into the academic lessons where most of this sedentary time is accumulated. Movement integration (MI) can be defined as the inclusion of physical activity of any intensity level into academic lessons [20,21]. Previous studies have shown that integrating PA into traditional lessons could break up or reduce sedentary time (especially prolonged sitting) and can increase academic benefits (such as motivation, the enjoyment of learning [22], or paying attention to a task [23]). Furthermore, integrating PA into some specific subjects (e.g., mathematics or language learning) could have beneficial effects on children’s academic performance [22,24,25]. In addition, students themselves have pointed out the values of physically active methods in contrast to the conventional and “boring way of learning” [26]. Studies have shown they prefer to be more physically active during academic lessons and believe that PA can prevent school-day tiredness [27].

Various opportunities for MI have been highlighted, such as (a) brain breaks, which are short, fun breaks from sitting and mostly do not involve curriculum-focused physical activities; (b) subject-based activities, where the acquisition of the content of the subject takes place through physical activity; and (c) incidental movement, which is based on a teacher’s instructions, agreements with students, and the classroom environment [27,28,29,30,31,32]. However, these kinds of changes require the ability of teachers to incorporate or integrate PA into their everyday teaching methods. Teachers often perceive barriers to this approach, including a lack of time due to competing pressures (e.g., academic testing and accountability) [33], lack of perceived MI competence [34], and a lack of support [35]. Martin and Murtagh [22] have indicated that the provision of lesson ideas, resources, and training to implement active academic lessons would increase teachers’ interest in using active methods in their lessons. Therefore, teacher training in MI should be an integral part in the implementation of comprehensive school-level interventions. Furthermore, it has been emphasized that research should focus on developing training, resource and equipment support, and identifying means of optimizing teacher and school buy-in—particularly for those teachers and heads of school who see little benefit in MI [36].

The present study contributes new data to the growing area of research of systematically developed school-based PA programs. Our findings are based not only on the theoretical paradigm of individual behavior change, but also on the vaster and more systemic view of changing school culture as a whole on the basis of social practice theory [37]. The main aim of this paper is to present the design process and implementation of teacher training modules—‘Active Lessons’ (AL)—to facilitate MI into academic lessons as part of the comprehensive school-based PA intervention program [38]. The study offers important insights into the design process and its successes and failures, describing the development stages of training modules and the material toolbox throughout the co-creation process with teachers. The follow-up study presents teachers’ evaluations of their MI practices after the seminars and adds further information regarding the use of teacher training to facilitate MI implementation.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Context

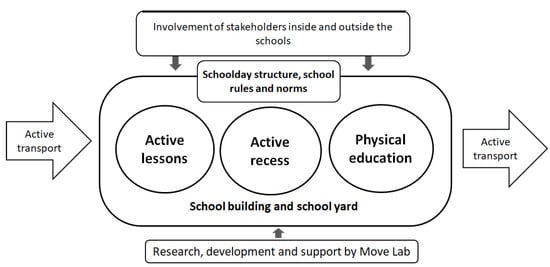

The development and implementation of the AL teacher training module was one of the focuses of the school-based multicomponent PA intervention program, Schools in Motion (SIM), in Estonia (for further information see Mooses et al. [38]). The main purpose of the intervention program was to decrease sedentary time and increase PA during the school day through changes in whole school culture and practices. Intervention and development modules were focused on the involvement of students, teachers, and the school board to promote AL, active breaks, active transport, and the school’s physical environment supporting PA during the school day (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schools in Motion’s general model (Mooses et al. [38]).

In 2016, 10 comprehensive schools began to participate in a 4-year pilot period. The pilot schools’ participation was based on their own motivation and the agreement of the principal. The entire development and implementation process was based on co-creation, with the schools giving important input for changes and eliciting new social practices [38], which are considered a preliminary condition for a change in general school culture. In 2021, the program has scaled up and 148 schools have joined the network out of the 512 comprehensive schools in Estonia.

2.2. Study Design and Participants

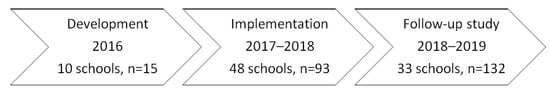

The general model of the study process, timeline, and participants is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Timeline, schools, and teachers’ participation in development, implementation, and follow-up study.

2.2.1. Theoretical Framework

During the development process of the teacher training modules, special attention was given to choosing theoretical frameworks to help support teachers’ readiness and skills to integrate opportunities for PA into academic lessons. Development was based on two theoretical frameworks: self-determination theory [39] and social change practice theory [37]. Self-determination theory is used to support teachers’ capabilities and individuals’ motivation via three basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness [39]. Due to the above, teachers had the flexible opportunity to plan their own lessons and select MI methods supported by a practical approach and the introduction of new MI methods.

The social change practice (SCP) theory-based approach emphasizes that the change we need in planning is to not focus only on individuals’ capabilities for change, but also to consider the wider socio-material environment, including meanings, existing practices and skills, traditions, supportive tools (e.g., materials and the physical environment), and social networks [37]. Support for change is needed in the following elements: (1) changing the meaning of PA in the learning context (e.g., PA during lessons not seen as a waste of time, but a supporter of the learning process and academic achievement) [40]; (2) developing the teachers’ skills and self-efficacy for MI [41]; (3) providing supportive tools (e.g., practical materials and ideas) [41]; and (4) supporting changes in school culture as a whole, including school administrators [36,42] and social networks.

Our task to design teacher training seminars involves multifaceted action research and ensuring that the new practices work in real-world school settings [43]. Based on theoretical frameworks, a general model of teacher training seminars and materials was planned and developed.

2.2.2. Development Process: Design and Piloting

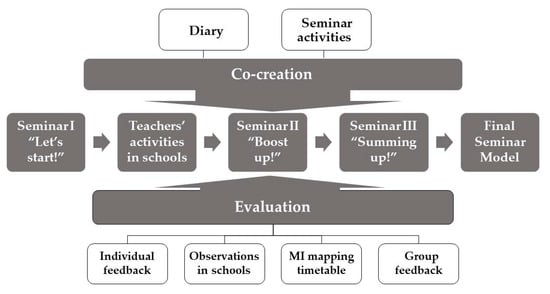

As part of the whole school intervention, teachers from all 10 SIM pilot schools were invited to take part in the development process of designing and piloting AL teacher training seminars. The invitations were sent by e-mail. Fifteen female teachers from nine schools gave their consent to participate in the pilot phase in 2016. The development phase consisted of planning and carrying out seminars, co-creation with teachers, evaluation, and finalizing the seminars model. The development and implementation process were monitored and evaluated (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phases of the design process for the teacher training seminars in the Schools in Motion program.

While the focuses of the first seminar were to increase awareness and provide skill development for MI, the second seminar focused more on feedback and exchanging experiences, as well as empowering and motivating the teachers. Examples of some of the MI methods and activities used both indoors and outdoors are presented in Supplementary Materials File S1. A third seminar with teachers was planned in order to evaluate and summarize the whole design process of the teachers’ seminars after two meetings and a practical period in schools. In addition, school principals also participated in this seminar, where they focused on how as leaders they can support a more physically active school culture. The importance of the principals’ support has been emphasized by previous studies [44].

Co-creation and teachers’ collaboration have been identified as the most important supportive resources for MI sustainability [45]. For co-creation, two main methods were used: (1) to support teacher’s autonomy and expertise as creators, individual diaries were used to collect their experiences, with an aim to share their ideas with other participants; and (2) group work for creating ideas was used during seminars to support relatedness between the teachers.

Diaries for mapping teachers’ ideas and practices in real-life situations in the classroom using MI methods were developed by the AL team and were distributed in Seminar I. The use of diaries as a co-creation method was planned during the time period between the two seminars. Filling in the diary was a voluntary but suggested task that asked teachers for their expertise and collaboration. Two weeks were planned for filling in the diary. A reminder was sent to all participants at the beginning of both weeks.

Seminar group work for developing MI methods was planned to support teachers’ autonomy, expertise, relatedness, and ability to form and practice new skills. In both seminars, specific co-creation activities were planned for creating and sharing MI ideas using simple and sometimes recycled equipment like paper plates, playing cards, or Lego blocks.

2.2.3. Supporting Materials

The AL team developed easy-to-use MI materials for multifunctional and flexible use, the importance of which have been emphasized in previous studies [33,46]. Teachers were asked to give feedback on the possibilities for their usage. They were also asked for suggestions for changes, as teacher engagement has been highlighted as a more effective way to create practical materials [47]. All toolbox materials created were handed out at the end of both seminars as a motivational and accessory boost for the teachers. A brief description of the materials is presented in our supplementary material (Supplementary Materials File S2).

2.2.4. Evaluation of the Design Process

Individual feedback via an ‘Idea board’’ was planned at the end of each seminar. Teachers were asked: What was valuable in today’s seminar? What should be changed in the seminar? Which of the activities you practiced today will you definitely use for MI in your lessons? Describe your expectations for the next seminar.

Additionally, lesson observations after the first seminar were carried out by AL team members and all teachers who participated in the pilot phase. A personal agreement was made with every teacher and observations were planned at a time comfortable for the teachers. At least one 45 min lesson was observed.

The MI timetable poster was developed with the aim to obtain feedback, to serve as a reminder, to record teachers’ preference to conduct MI activities, and to also record the frequency that they are conducted (Supplementary Materials File S3). To spare teachers’ valuable time, the timetable was created as icon-based and was fillable with only a few marks. Teachers were asked to fill in the timetable based on their lesson plan and to mark down what kind of MI activities they used each day, including their approximate duration and the intensity of the PA.

Group feedback was planned to evaluate and summarize the entire design process after two meetings and the practice period (Figure 2). Supporting questions were provided during group feedback: (1) How many seminars per year should there be to support the sustainability of MI activities? Duration?; (2) What should the content and structure of the seminar be?; (3) Which materials would support MI in academic lessons? What kind of tools or materials should the toolkit for teachers contain?; (4) Is there any other way the AL team could support teachers?; and (5) Additional suggestions.

2.3. Implementation and Follow-Up Study

After designing and piloting the teacher training seminars in 2016, the final model was adopted in 2017–2018 as one of the key elements of the comprehensive school-based program (Mooses et al. [38]). By 2017, 13 schools participated in the SIM program, and by 2018 48 schools had joined. In addition to AL training seminars, several co-creative seminars and workshops with school principals and other school community members were held to implement the whole school approach.

At the end of 2018, after the AL seminars, a follow-up study was carried out. All teachers who had participated in seminars during this period (2016–2018), were invited to participate in the survey (n = 193). The final sample consisted of 132 (68.4%) teachers from 33 schools, who all were teaching in primary or middle school (7–16-years old students). Teachers’ self-reflections were used to examine: (1) teachers’ self-confidence in using MI and MI practices; (2) teachers’ attitudes towards MI in the learning process; and (3) teachers’ reflections about the format and toolbox materials of training seminars. The web-based, multiple-choice questionnaire was anonymous and completed between December 2018 and January 2019. Teachers evaluated their use of MI practices before and after the seminars retrospectively. The difference in the distribution of their answers was assessed using a Chi-Square Test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Development and the Design of the Teacher Training Model

As a result of development and the piloting process the final teacher training model was created. The content, methods, and schedule of both the pilot phase seminars and final model are presented in detail in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Content, methods, and schedule of teacher training seminar I “Let’s start!”

Table 2.

Content, methods and schedule of teacher training seminar II “Boost up!”.

In general, the overall structure, content, methods, and timeframe of the seminars remained as they were in the pilot seminars. However, some changes and adaptions were made to the final model.

The first seminar started with the mapping of teachers needs and readiness for MI. Teachers’ previous practices and obstacles experienced while integrating PA into learning methods were also discussed (Table 1). The PA recommendations and an overview of children’s PA in Estonia were presented. In addition, since prolonged sedentary time is currently the dominant practice in Estonian schools [15], it was extremely necessary to focus on the links between learning and MI during academic lessons. As previous studies have shown, emphasizing the learning outcomes is more motivating for teachers than focusing on health outcomes alone [48].

Both seminar days consisted of plenty of ideas and practical experiences. The MI methods (brain breaks, academic-infused PA, incidental PA, etc.) were integrated into every part of the seminars, including group work, pair discussions, and reflective tasks. Several environments were used as well (hallways, stairs, outdoors). All of these MI methods were easily transferable to academic lessons on any kind of topic. In the feedback from the ‘Idea board’ at the end of the seminars (Supplementary Materials File S4), teachers strongly emphasized the importance of seminar practicality, which should be supported by theoretical background and knowledge. Additionally, the teachers reflected on the value of the wide range of methods. The variety (cross-curricular, universal, not age-specific) of shared MI methods remained one of the focuses in the final form of the seminar. These results are consistent with previous intervention studies that have shown that a practical approach (such as modelling and hands-on activities) plays a very important role in improving or acquiring skills [41,49].

An outdoor learning session was planned as part of both seminars. Despite the challenges of outdoor teaching practices such as uncertain weather conditions (rain, strong winds, low temperatures), the overall feedback after the seminars was overwhelmingly positive and expressed satisfaction for the opportunity to practice outdoors. As being outdoors was considered an important part of the seminars, adaptions were made related to the time allocated for outdoor learning issues. Therefore, the time to practice outdoors methods was increased for the final model.

As it was important to gain an overview of the teachers’ personal experiences of MI methods in real-life situations and to provide time for personal practice, a practice period was carried out between the two seminars. Observations in schools during the practice period between the two seminars were conducted by the AL team to examine practical issues, students’ motivation, and contentment with the MI methods. The school visits confirmed that the MI methods provided in the seminars are suitable among different age groups and subjects and can be conducted outside the classroom. In addition, many teachers also used their own MI methods, which was a high value experience for the AL team and significant input in the development process. Though observations were planned as an evaluation method in the beginning, they turned out to be a valuable co-creation tool, providing ideas and practical solutions for the AL team for activities and themes for seminars.

During the practice period, the MI timetable (Supplementary Materials File S3) for mapping teachers’ activities was used. As teachers clearly indicated that the MI timetable method was excessively time-consuming, there were too many focuses to follow (method, intensity, time), and it overlapped with their diary activities, this method failed. None of the teachers filled in the MI timetable as required; therefore, it was excluded from the final model.

Based on input from the observations, the practice period (4–5 weeks) in schools remained in the final model of the teacher training, as it appears to be an important element and provides the possibility to practice and reflect on the MI experiences. Additionally, due to previous studies which have highlighted the importance of feedback and the exchange of experience between teachers in increasing teachers’ competence and implementation in MI [48], the opportunity to share best practices and obtain new additional methods and ideas was created in the second seminar (Table 2). To provide a more in-depth discussion and further feedback on the practical period between the seminars, the respective timeframe was doubled in the final model.

The importance of ready-to-use materials for MI was strongly confirmed by the teachers’ feedback, in line with previous studies [22,41,46,48]. The teachers pointed out time and the workspace factor as the main barriers that affect their attitude towards using MI in their lessons [35,46]. Preparation for the AL can be time-consuming and the completion of the curriculum can be stressful [33,35,46,48,50]. In addition to shared materials (Supplementary Materials File S2), the teachers also outlined the importance of shared links to websites providing different physical activity methods, new ideas, and instructions for movement games. It was clearly noted that the personal toolkit would motivate and support teachers to use MI in their lessons more often. The need to provide a variety of ready-to-use materials was repeatedly emphasized as a necessary input for starting to use MI methods, and therefore these were incorporated in the final model.

For finalizing the design and piloting process, the third seminar was carried out in order to obtain group feedback. To form the final model of teacher training seminars, group discussions entitled ‘The dream MI seminar for teachers’ were conducted. In this study, the two-day seminar format was strongly favored by teachers and even more seminar days were preferred to support the sustainability of MI activities. Teachers also emphasized the importance of sharing experiences (both positive and negative). This differs from the study of van der Berg et al. [48] in which teachers did not express the need to have training courses, but instead preferred short workshops. The difference between the studies may lie in previous teaching practice; for example, it is common to use conventional methods in Estonia [15] and the acquisition of the new practices for MI may need more support. Considering the financial aspect of training, the two-day seminar framework was fixed and adapted as more realistic. According to the teachers, the ideal model should involve approximately four additional follow-up seminars per year (around 4–6 academic hours each) to keep them supported and motivated. This was taken into consideration by the AL team with the aim of planning and providing the in-service training system.

The need for additional ideas and games was mentioned often in both individual feedback and in the group feedback during the final seminar. Teachers’ motivation to try new methods can be clearly observed in the individual feedback at the end of seminars. Although each teacher had to indicate at least one activity from the seminar to test during the practice period, significantly more activities were usually listed. The need for new ideas and games was highlighted as an expectation for the next seminars. Based on the teachers’ input, a web-based, open-access “IdeaBank” was created using idea collections from the teachers’ diaries. Filling in the diary during the practice period provided an opportunity to supplement the “IdeaBank” and so it was used in the final model.

The directors also participated in the third seminar, where their feedback for teacher training and the whole school approach was collected. They pointed out that to promote a physically active school culture and AL it is important to have a whole school approach involving teachers, school leaders, and students. The importance of the input from a variety of teachers was additionally pointed out. Previous studies have also suggested a whole school approach [36,42] and teacher involvement in the early stages of intervention [51,52]. As for teacher training, they considered it to be useful and supported the teachers’ participation in the seminars. In their view, teacher training seminars could take place regularly as a one-day training event. They also emphasized the importance of a toolbox for teachers to include various games and supporting materials. This is in line with previous studies where school principals also recommended providing materials that require minimal preparation time from the teacher [21,48,53].

As the teacher training seminars were part of an SIM program, the need for a common channel of communication and information sharing such as Facebook was mentioned by participants of the third seminar. To support changes throughout social networks, and to share the ideas and practices of MI and a whole school approach, the SIM community group “Liikuma Kutsuv Kool” (Schools in Motion) was created on Facebook [54]. It is still viable and continually progressing, reaching more than 3800 members in 2022.

The main tips and lessons learnt from the development process of designing a teacher training program focusing on MI are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Main tips and lessons learnt from the development process.

3.2. Results of Implementation and Follow-Up Study

The piloted model was provided for AL training seminars for all SIM schools as a part of the general program. Between 2016 and 2018, 10 two-day seminars for teachers were carried out by the AL team in regional settings. After the seminars, in a follow-up study carried out in 2018–2019, the teachers’ readiness, practices, and attitude to MI were examined. Additionally, teachers’ reflections about format and toolbox materials of the training seminars were studied.

The AL seminar model could be a facilitative strategy for MI in academic lessons according to the teachers’ self-evaluations. Additionally, most of the teachers (96%) confirmed that after the training they feel more self-confident in integrating movement into their lessons. It is worth noting that 98% try to follow the principles of MI in their lessons so that students do not sit for 45 consecutive minutes. As the AL seminars emphasized practicality, the practice and exchange of experiences can be a suitable format to help support teachers’ self-confidence.

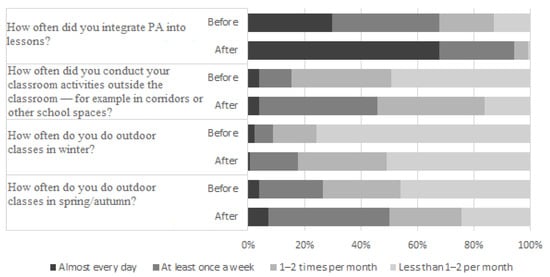

Teachers evaluated their use of MI practices before and after the seminars retrospectively on four different occasions. The distribution of evaluations of MI practices before and after the seminars were significantly different for all four questions (p < 0.05) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Teachers’ responses to the use of MI methods before and after AL seminars.

The proportion of teachers who reported using MI almost every day after the AL seminars was 68% compared to 30% before the AL seminars. In addition, the proportion of teachers who reported conducting their lessons at least once a week outside the classroom increased almost four times (42% after the AL seminars vs. 11% before the AL seminars). Similarly, teachers reported the use of outdoor teaching practices at least once a week more often after the AL seminars (for both the spring and winter periods). Results indicated that the daily use of MI, teaching outside the classroom, and outdoor learning were generally not common practices before the AL seminars.

Based on the teachers’ experience, the impact of MI on students’ lessons was evaluated. Similar to previous studies [22], almost all teachers (98%) agreed that the students enjoy MI during lessons as it makes the learning process more interesting. Almost 65% of the teachers found that students became restless when there was no MI during lessons. This is in accordance with the students’ experience, as students themselves have confirmed that prolonged sitting can be tiring during academic lessons [27]. It is important to emphasize that most of the teachers (88%) pointed out that students are more focused after using MI. However, 40% of teachers found that it can be difficult for students to calm down after these activities. This finding has important implications for developing calm-down activities and integrating them into seminars.

As in the pilot phase, the follow-up study also confirmed the need for a multi-stage teacher training model and for supportive materials. It is important to highlight that only 4% of participants considered that one day was sufficient for AL teacher training seminars. A total of 41% of teachers considered 2–3 days of training as important for acquiring the basic knowledge of MI and 34% noted that the training module should be even longer. The need for additional AL seminars should be also emphasized. A total of 71% of the teachers confirmed the necessity of additional trainings, and 85% thought they should take place 1–2 times a year.

As with previous studies [22,41,46,48] this research has strongly confirmed that ready-to-use materials are valuable supporting resources. In our study, 99% of the teachers agreed that the material delivered in seminars significantly contributed to them using MI during lessons. Additionally, 60% of the teachers were also using the web-based Ideabank for finding new ideas for MI. This highlights the need for AL seminars and MI supportive materials.

According to the results, 96% of teachers reported that they felt supported by school principals to introduce MI into their lessons and the school day, and emphasized the importance of a whole school approach [37]. Previous studies have also confirmed that involving school principals is important for promoting changes in school culture [42].

3.3. Strengths and Limitations

One of the strengths of this study includes the design methods—the co-creative approach and the iterative process ensure close cooperation with teachers in the formation of a training model that is in accordance with teachers’ needs and supports MI practice in real school situations. The second strength is the practical input—the practical implications of the design process are crucial to the implementation process and research. The limitations of this study design include a possible bias, as one of the analysis methods was reflections by the AL team which was based mainly on qualitative data. Therefore, some subjective interpretations may have influenced the results and conclusions. In addition, the results of the follow-up study should be interpreted with mild caution as 1/3 of the teachers did not respond to the e-mailed questionnaire. However, even with some bias, the results of the follow-up study still give valuable feedback to the teacher training modules.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a detailed description of the design and development process of a teacher training model to support teachers’ readiness and skills to integrate more MI methods into academic subjects. To design a feasible and sustainable model, flexible co-creation methods and an iterative process were used and supported by appropriate theoretical frameworks. Co-creation, piloting, and a follow-up study indicated that the supportive two-day training model, a practical and flexible approach, ready-to-use resources, and allocated time and autonomy for practice (supported by a whole school approach) are key elements in designing a teacher training framework that aligns with teachers’ needs. To support the use of MI methods by teachers, such trainings for qualified teachers should become readily available for continuing professional development. In addition, further studies should focus on investigating the incorporation of the training modules on MI into initial teacher-training curriculums. This study’s results can be used by researchers and practitioners to develop targeted interventions aimed at promoting teachers’ education of MI and thereby foster a more physically active school culture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su14095484/s1, File S1: Examples of MI methods used during teacher training seminars. File S2: Teachers toolbox materials (“Number cards”; “Alphabet cards”; “Bead cards”; “Alphabet poster”). File S3: Movement integration timetable poster. File S4: “Idea board” for individual feedback at the end of the seminars.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.K. (Merike Kull), M.K. (Maarja Kalma), K.M. (Kerli Mooses) and K.M. (Katrin Mägi); methodology: M.K. (Merike Kull), M.K. (Maarja Kalma), K.M. (Kerli Mooses) and K.M. (Katrin Mägi); formal analysis: M.K. (Merike Kull), M.K. (Maarja Kalma), K.M. (Katrin Mägi) and E.M.; investigation: M.K. (Merike Kull), M.K. (Maarja Kalma), K.M. (Kerli Mooses) and K.M. (Katrin Mägi); writing—original draft preparation: M.K. (Merike Kull), M.K. (Maarja Kalma) and K.M. (Katrin Mägi); writing—review and editing: E.M., M.K. (Merike Kull), M.K. (Maarja Kalma), K.M. (Katrin Mägi) and K.M. (Kerli Mooses); visualization: M.K. (Merike Kull), M.K. (Maarja Kalma) and E.M.; supervision: M.K. (Merike Kull). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

During the period from 2014 to 2019, program development was supported by the Research and Innovation Foundation of the University of Tartu, the Estonian Science Foundation program ‘TerVe’, the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Council of Gambling Tax, the Ministry of Education and Science, Tartu City, the association Sport for All and the Estonian Research Council, grant number IUT 20-58. Since 2020, the program has been supported by the project ‘Increasing the physical activity of schoolchildren’ funded by EEA grants (grant 2014-2021.1.05.20-0004), under the program ‘Local Development and Poverty Reduction’ co-financed by the Ministry of Social Affairs and the University of Tartu. The funders gave financial support for the development of the program. The funders were not involved in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or in writing the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu (approval no. 242/T-17).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the schools and partners participating in the Schools in Motion program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Guinhouya, B.C.; Samouda, H.; de Beaufort, C. Level of physical activity among children and adolescents in Europe: A review of physical activity assessed objectively by accelerometry. Public Health 2013, 127, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooses, K. Physical Activity and Sedentary Time of 7–13 Year-Old Estonian Students in Different School Day Segments and Compliance with Physical Activity Recommendations; University of Tartu Press: Tartu, Estonia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Verloigne, M.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Maes, L.; Yıldırım, M.; Chinapaw, M.; Manios, Y.; Androutsos, O.; Kovács, E.; Bringolf-Isler, B.; Brug, J.; et al. Levels of physical activity and sedentary time among 10- to 12-year-old boys and girls across 5 European countries using accelerometers: An observational study within the ENERGY-project. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunton, G.F.; Do, B.; Wang, S.D. Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in children living in the U.S. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.A.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Brussoni, M.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Ferguson, L.J.; Mitra, R.; O’Reilly, N.; Spence, J.C.; Vanderloo, L.M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: A national survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Kang, S.; Qiu, L.; Lu, Z.; Sun, Y. Association between physical activity and mood states of children and adolescents in social isolation during the COVID-19 epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Abdeta, C.; Abi Nader, P.; Adeniyi, A.F.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Andrade Tenesaca, D.S.; Bhawra, J.; Brazo-Sayavera, J.; Cardon, G.; et al. Global Matrix 3.0 physical activity report card grades for children and youth: Results and analysis from 49 countries. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, S251–S273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mäestu, E.; Kull, M.; Mooses, K.; Mäestu, J.; Pihu, M.; Koka, A.; Raudsepp, L.; Jürimäe, J. The results from Estonia’s 2018 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, S350–S352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.M.; Landry, M.J.; Gustat, J.; Lemon, S.C.; Webster, C.A. Physical distancing≠ physical inactivity. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, M.; Husson, H.; DeCorby, K.; LaRocca, R.L. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD007651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, D.; Corbin, C.B.; Dale, K.S. Restricting opportunities to be active during school time: Do children compensate by increasing physical activity levels after school? Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2000, 71, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Advocacy for Physical Activity (GAPA) the Advocacy Council of the International Society for Physical Activity and Health (ISPAH). NCD prevention: Investments [corrected] that work for physical activity. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 709–712. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pate, R.R.; Davis, M.G.; Robinson, T.N.; Stone, E.J.; McKenzie, T.L.; Young, J.C.; American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Physical Activity Committee); Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. Promoting physical activity in children and youth: A leadership role for schools: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Physical Activity Committee) in collaboration with the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and Cardiovascular Nursing. Circulation 2006, 114, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mooses, K.; Mägi, K.; Riso, E.M.; Kalma, M.; Kaasik, P.; Kull, M. Objectively measured sedentary behaviour and moderate and vigorous physical activity in different school subjects: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Greeff, J.W.; Bosker, R.J.; Oosterlaan, J.; Visscher, C.; Hartman, E. Effects of physical activity on executive functions, attention and academic performance in preadolescent children: A meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, K.I.; Hillman, C.; Stillman, C.M.; Ballard, R.M.; Bloodgood, B.; Conroy, D.E.; Macko, R.; Marquez, D.X.; Petruzzello, S.J.; Powell, K.E.; et al. Physical activity, cognition, and brain outcomes: A review of the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, R.A.; Kuzel, A.H.; Vaandering, M.E.; Chen, W. The association of physical activity and academic behavior: A systematic review. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, D.M.; Centeio, E.E.; Beighle, A.E.; Carson, R.L.; Nicksic, H.M. Physical literacy and comprehensive school physical activity programs. Prev. Med. 2014, 66, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, L.B.; Webster, C.A.; Beets, M.W.; Egan, C.; Weaver, R.G.; Harvey, R.; Phillips, D.S. Development of the system for observing student movement in academic routines and transitions (SOSMART). Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 44, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.A.; Russ, L.; Vazou, S.; Goh, T.L.; Erwin, H. Integrating movement in academic classrooms: Understanding, applying and advancing the knowledge base. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Murtagh, E.M. Teachers’ and students’ perspectives of participating in the ‘Active Classrooms’ movement integration programme. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, L.A.; Jowers, E.M.; Errisuriz, V.L.; Bartholomew, J.B. Physically active vs. sedentary academic lessons: A dose response study for elementary student time on task. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mullender-Wijnsma, M.J.; Hartman, E.; de Greeff, J.W.; Doolaard, S.; Bosker, R.J.; Visscher, C. Physically active math and language lessons improve academic achievement: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20152743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reed, J.A.; Einstein, G.; Hahn, E.; Hooker, S.P.; Gross, V.P.; Kravitz, J. Examining the impact of integrating physical activity on fluid intelligence and academic performance in an elementary school setting: A preliminary investigation. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, J.M.; MacPhail, A.; Dillon, M. “I want to do it all day!”—Students’ experiences of classroom movement integration. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 94, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uibu, M.; Kalma, M.; Mägi, K.; Kull, M. Physical Activity in the classroom: schoolchildren’s perceptions of existing practices and new opportunities. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Lambourne, K. Classroom-based physical activity, cognition, and academic achievement. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, S36–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, H.T.; Agergaard, S.; Stylianou, M.; Troelsen, J. Diversity in teachers’ approaches to movement integration: A qualitative study of lower secondary school teachers’ perceptions of a state school reform involving daily physical activity. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar, M.T.; Murphy, S.K.; Rowe, D.A.; Golden, J.; Shields, A.T.; Raedeke, T.D. Effects of a classroom-based program on physical activity and on-task behavior. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 2086–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, R.; Murtagh, E.M. An intervention to improve the physical activity levels of children: Design and rationale of the ‘Active Classrooms’ cluster randomised controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2015, 41, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, N.K.; Sutherland, R.L.; Hope, K.; McCarthy, N.J.; Pettett, M.; Elton, B.; Jackson, R.; Trost, S.G.; Lecathelinais, C.; Reilly, K.; et al. Implementation of a school physical activity policy improves student physical activity levels: Outcomes of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, T.L.; Hannon, J.C.; Webster, C.A.; Podlog, L. Classroom teachers’ experiences implementing a movement integration program: Barriers, facilitators, and continuance. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 66, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, J.B.; Jowers, E.M. Physically active academic lessons in elementary children. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, S51–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McMullen, J.M.; Martin, R.; Jones, J.; Murtagh, E.M. Moving to learn Ireland—Classroom teachers’ experiences of movement integration. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 60, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routen, A.C.; Johnston, J.P.; Glazebrook, C.; Sherar, L.B. Teacher perceptions on the delivery and implementation of movement integration strategies: The CLASS PAL (Physically Active Learning) Programme. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 88, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vihalemm, T.; Keller, M.; Kiisel, M. From Intervention to Social Change: A Guide to Reshaping Everyday Practices; Routledge/Ashgate Publishing Ltd: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mooses, K.; Vihalemm, T.; Uibu, M.; Mägi, K.; Korp, L.; Kalma, M.; Mäestu, E.; Kull, M. Developing a comprehensive school-based physical activity program with flexible design—From pilot to national program. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, H.E.; Beighle, A.; Morgan, C.F. Effect of a low-cost, teacher-directed classroom intervention on elementary students’ physical activity. J. Sch. Health 2011, 81, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.; Webster, C.A.; Weaver, R.G.; Stodden, D.F.; Brian, A.; Egan, C.A.; Michael, R.D.; Sacko, R.; Patey, M. Evaluation of a classroom movement integration training delivered in a low socioeconomic school district. Eval. Program Plan. 2019, 73, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.A.; Glascoe, G.; Moore, C.; Dauenhauer, B.; Egan, C.A.; Russ, L.B.; Orendorff, K.; Buschmeier, C. Recommendations for administrators’ involvement in school-based health promotion: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.S.; Salvo, D.; Ogilvie, D.; Lambert, E.V.; Goenka, S.; Brownson, R.C.; Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. Scaling up physical activity interventions across the globe: Stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet 2016, 388, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, S.; Pawlowski, C.S.; Skovgaard, T.; Pedersen, N.H.; Troelsen, J. Exploring implementation of a nationwide requirement to increase physical activity in the curriculum in Danish public schools: A mixed methods study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, L.S.; Bredahl, T.V.G.; Skovgaard, T.; Elf, N.F. Identification of usable ways to support and “scaffold” Danish schoolteachers in the integration of classroom-based physical activity: Results from a qualitative study. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 65, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, M.; Kulinna, P.H.; Naiman, T. “… because there’s nobody who can just sit that long”: Teacher perceptions of classroom-based physical activity and related management issues. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2016, 22, 390–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibbe, D.L.; Hackett, J.; Hurley, M.; McFarland, A.; Schubert, K.G.; Zchultz, A.; Harris, S. Ten Years of TAKE 10!®: Integrating physical activity with academic concepts in elementary school classrooms. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, S43–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, V.; Salimi, R.; de Groot, R.H.M.; Jolles, J.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Singh, A.S. “It’s a battle... You want to do it, but how will you get it done?": Teachers’ and principals’ perceptions of implementing additional physical activity in school for academic performance. J. Phys. Act. Health 2017, 14, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garet, M.S.; Porter, A.C.; Desimone, L.; Birman, B.F.; Yoon, K.S. What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2001, 38, 915–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quarmby, T.; Daly-Smith, A.; Kime, N. “You get some very archaic ideas of what teaching is…”: Primary school teachers’ perceptions of the barriers to physically active lessons. Education 2019, 47, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Kriemler, S. Reflections on physical activity intervention research in young people—Dos, don’ts, and critical thoughts. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christian, D.; Todd, C.; Davies, H.; Rance, J.; Stratton, G.; Rapport, F.; Brophy, S. Community led active schools programme (CLASP) exploring the implementation of health interventions in primary schools: headteachers’ perspectives. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMullen, J.; Kulinna, P.; Cothran, D. Chapter 5 physical activity opportunities during the school day: Classroom teachers’ perceptions of using activity breaks in the classroom. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2014, 33, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facebook Group of the School in Motion. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/liikumakutsuvkool (accessed on 17 March 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).