Abstract

Our research was intended to find out whether social networking is recognized and experienced as leisure or should be considered liquid leisure because its borders are fluid. This aim was connected to the broader question of whether there are still clear borders between work, leisure, and other life aspects. The research was designed as a cross-sectional ex-post-facto study. The survey examined data collected through a structured questionnaire completed and returned by 3451 respondents aged 15+ selected from the general population of the Czech Republic. The statistical significance of hypotheses was tested using χ2 statistics for two-way (C × R) and three-way (C × R × L) contingency tables. Only 752 (21.79%) respondents reported not having or using an online social network account. Even though there is no reason why social networking should not be considered leisure, there was a considerable discrepancy between those who considered social media a leisure activity (8.2%) and those who did not (78.21%). Therefore, this kind of leisure activity is conceptualized in this paper as a specific liquid leisure.

1. Introduction

Online social networks (OSNs) are web-based tools that allow users around the world to connect with their friends, families, professional groups, and social circles through social interaction and the sharing of common interests. The significance of social networking has risen, especially in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic when in person social contact was limited [1]. The global response of governments (including the Czech Republic) during the COVID-19 pandemic included nationwide (or regional) shutdowns, border closings, and the restriction of people’s movement [2]. As a result, leisure opportunities were severely limited to more individualized, restricted forms (e.g., exercise at home and walking in a limited form). Any form of leisure that brought people into close contact, from amusement parks to museums, was closed in physical form to the public. Even some professional and recreational sports have been postponed or canceled altogether.

OSNs have allowed individuals to remain emotionally connected despite social distancing. At the same time, prolonged time spent on OSNs has raised concerns related to their impacts on physical and mental health. The most used OSNs, which have millions of daily active users, include Facebook (2910), YouTube (2562), WhatsApp (2000), Instagram (1478), Weixin/WeChat (2263), and TikTok (1000) [3]. The conscious and regulated use of social networking sites is associated with well-being, but excessive time is reportedly associated with a range of negative mental health consequences, such as psychological problems, low emotional stability, and a higher risk of depression or anxiety [4,5,6]. Negative consequences often arise when digital technology use is impulsive, compulsive, unregulated, or addictive [7].

Social media is both physically and psychologically addictive [7,8,9,10]. Thus, behavioral addictions such as OSN addiction can be viewed from a biopsychosocial perspective [11]. Social media addiction is defined as a psychological state of dependence of individuals on social media use that can be demonstrated through an indulgent paradigm of social media search and that interferes with other normal activities [9]. OSN addiction includes mood alteration, saliency, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, conflict, and relapse [9,10].

It is important to note that OSNs are easily accessible and thus very commonly used on smartphones. Here, young people lose track of time, which results in tasks being not completed on schedule [12]. People move between two worlds, i.e., the physical world and cyberspace. The existence of these worlds is parallel but disjointed. Das states that “with the proliferation of digital technologies in our everyday lives and the increased usage of networking sites, these two realms are slowly converging into one another” [13].

New technologies have also changed the experience of leisure in families and homes, bringing new experiences and control into these experiences [14]. Household members do not have to experience leisure activities homogeneously (watching TV together); instead, they have more freedom in their choice of leisure activities, e.g., they do not have to be tied to specific content, time, and people. Furthermore, they can flexibly engage in their leisure activities through OSNs with anyone from anywhere [15].

Leisure consists of activities in which individuals participate during their free time outside of compulsory time such as work, school, and sleep. Leisure is an activity based on open awareness, free choice, and self-determination, and it includes activities such as reading, sports, climbing, social activities, chatting, and shopping [16,17]. Stebbins [18] defines leisure as an unforced activity that is set in a particular context and that is realized in free time. People want to participate in this activity using their resources and abilities because the activity satisfies or fulfills them. Kaplan [19] reported that leisure includes activities and experiences that people perceive as bringing pleasure in anticipation or memories, providing opportunities for recreation, personal growth, and service to others. Leisure can be objectively viewed as a period in which activities are realized, and it can be viewed subjectively as representing a state of mind. The subjective perception of leisure is not necessarily related to objective leisure [20]. A psychological state of mind occurs in existential equilibrium, which is achieved when an individual perceives a balance between the challenges associated with life and their ability to face or solve these challenges. When an individual asserts and expands their competencies, they can experience a state of deep engagement in which they become comfortably immersed in the chosen behavior. This is an experience of flow, a term developed by Csikszentmihalyi as a metaphor for a process that seemingly needs no conscious intervention on the part of the individual [21,22]. Flow is generally understood as a deeply pleasurable psychological state in which complete absorption in a given task leads to a range of positive experiential qualities. This experience usually occurs when an individual is confronted with a task that they are able to accomplish and on which he or she is also able to fully concentrate. Novak and Hoffman presented flow as a state occurring while navigating a network, characterized by a fluid sequence of responses facilitated by the interactivity of the machine that is perceived as intrinsically pleasurable, accompanied by a loss of self-awareness, and ultimately empowers the self. To experience flow in an activity, users must perceive a balance between their skills and the challenges associated with the activity. However, it is important that their skills and challenges are above a critical threshold [23].

Leisure activities can improve the physical and mental health of individuals, and they are important for regulating the body and mind, relieving life stress, and providing enjoyable experiences [24,25]. The benefits of leisure activities include stress reduction, relaxation through participation in pleasurable experiences, and the creation of new social relationships [26]. New information and communication technologies have had major impacts on individuals’ leisure time. Accordingly, an increasing number of studies are considering the digital leisure activities offered by new media [27,28]. Leisure researchers have examined the digital leisure engagement of not only young adults [29,30,31] but also older adults [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

Contact limitations have forced people to use new ways of staying in touch and spending leisure time with family and friends [40,41]. The age of media users is related to their use of digital media for communication [42,43,44]. Czaja et al. [45] found that younger people adopt new technologies faster than older people. In addition, younger people were shown to more frequently use social media for communication purposes than older generations [44,46]. In contrast to age, the relationship between gender and media use has shown mixed results. Though some studies have shown no gender differences in the intensity of media use [47], other studies have shown that men use media more frequently and intensively than women [48]. However, other studies have shown that women prefer and use text messaging, social media, and online video chatting more frequently than men [49]. Despite these mixed results, age and gender may have played significant roles in the use of OSNs the during lockdown situation [40]. Social media allows new mothers to engage in personal leisure and gain a sense of belonging. In addition, new mothers tend to combine personal and family leisure activities, and they rely on social media for information about these activities [50].

Organizations also play a big role in the work/leisure balance, as leisure helps to increase work performance. Four constructs have emerged from research on perceived organizational leisure support that apply social exchange theory to organizations: instrumental leisure support, time-based leisure support, event-based leisure support, and community-based leisure support [51].

In addition to leisure, labor market changes in modern individualized societies are directly related to private, family, and partner lives [52]. These phenomena can have different impacts on different groups according to gender, age, profession, education, location, and social status [53,54].

Factors that manifest themselves in the labor market, such as globalization, new ways of organizing working time, unemployment, new forms of employment, and migration, are direct reflections of how people organize their private lives, e.g., cohabitation in partnerships and marriages, the birth and upbringing of children, leisure, and lifestyle. These changes have led to a new understanding of the relationship between the professional, public, and private domestic lives of individuals [53,54,55]. Most of these changes are a part of the concept of the work–life balance, which can be described as an evaluation of all the interrelated roles in working life. A successful work–life balance results from satisfaction with different life situations in accordance with one’s values [56]. Parker suggested that although work occupies only part of people’s lives, their leisure activities are undoubtedly conditioned by various factors associated with the way they work. People who work together at the same time and in the same space are focused on common goals or activities, which means they also share a common work experience, whether it is positive, negative, or neutral. It follows that for most people, leisure is shaped by how they respond to work, and its authority overrides other influences such as class and gender [57].

Blackshaw built on Csikszentmihalyi’s flow theory and then offered his own original theory of fluid leisure that considers some key questions regarding the present and future of leisure in people’s lives, as well as its implications for individuals’ ability to seize the opportunity for an authentic existence that is both magical and moral. In his analysis, he drew on the modernism of Zygmunt Bauman [58] and used his basic metaphor of fluid leisure to develop a number of relevant philosophical and socio-cultural ideas. Leisure time was examined in terms of its ability to create an authentic, artistic existence that is centered on bringing meaning into the life of the individual in a way that corresponds to the diversity and ambiguity of human experience [59]. In the concepts of liquid modernity and liquid leisure, it is the individual who has authority over their actions and engagement in leisure practices in modern society [57].

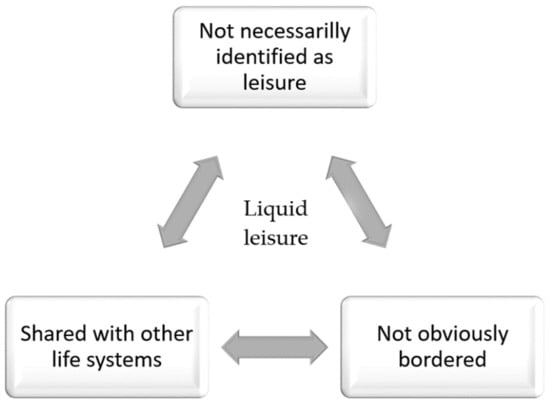

In the context of these definitions, it can be concluded that social networking fulfills almost all aspects of leisure activities. It is conducted outside compulsory time [39,60,61] and is relatively self-determined [62,63,64]. According to the literature, social networking satisfies or fulfills people’s needs for activities and/or experiences [65,66,67,68], brings pleasure [69,70], and provides opportunities for recreation [71], personal growth [72], and/or service [73]. Within this context, there are specific and widely discussed norms and constraints of behavior [74], and the relevant crucial questions considered in this study are: When social networking meets all these characteristics, why do people not recognize it as leisure time? If it is not leisure, what kind of time or experience is it? These questions are the logical results of the discrepancy in the results of data analysis. When we asked the respondents about their leisure activities, they often did not identify social networking as leisure because they apparently did not recognize it as such. However, when we asked whether they used OSNs, they often answered yes and were even able to describe the intensity and frequency of this activity. This discrepancy led us to the theoretical assumption that this kind of leisure is different in some ways from the classical understanding of leisure. Therefore, we suggest recognizing it as a specific kind of liquid leisure, which could be defined as an implicit leisure experience that is not framed by time and space, often shared with other activities, and not necessarily identified as explicit leisure (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schema of the conceptualization of liquid leisure.

Our research was intended to find out whether social networking is recognized and experienced as leisure or should be considered liquid leisure because its borders are fluid. This aim was connected with the broader question whether there are still clear borders between work, leisure, and other life aspects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The research was designed as a cross-sectional ex-post-facto study. This approach is used to measure and analyze influences of social factors on specific phenomena [75,76]. The investigation was conducted nationwide across the country. The studied context was part of a broader investigation that addresses issues of leisure and ICT skills, as well as examining key worldview issues, social threats, and deals with values research. The survey examined data collected through a structured questionnaire completed and returned by a total of 3451 respondents aged 15+ selected from the general population of the Czech Republic. The sample size was determined using the population proportions to achieve the proportional stratification of the sample [77]. Data collection was conducted via a questionnaire from September 2020 to January 2022. The questionnaire was delivered online using the Social Survey Project research instrument [78]. For respondents who were unable to complete the questionnaire online, face-to-face interviews or assisted completion were used. Due to the data collection method and the storage of the results on a database, we were unable to distinguish between online or paper entries, which is why we could not test for differences in the data collection methods. However, assisted filling did not exceed 10% of the collected questionnaires. Respondents were selected across the country using stratification sampling, with stratification criteria of gender, age, and community size; within stratification groups, the questionnaire was widely and randomly distributed to the population thanks to more than 200 volunteers who helped with questionnaire distribution. No inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied. The collected data can be considered representative according to Czech Statistical Office population reports [79] in terms of the gender and age of respondents, as well as the size of the municipality—in most stratification criteria, the difference between the population and the samples in the stratification criteria was less than 10%. The research was conducted using the internal Department of Christian Social Work Research Protocol for Quantitative Research.

2.2. Definition and Measurement of Variables

Gender (G) was identified by using a categorical closed scale consisting of the following categories: man (1682; 48.74%) and woman (1423; 52.72%).

The respondents’ age (A) was measured by using an open answer; consequently, age categories of 10-year lengths were created for the purposes of the survey: 15–24 (441; 12.78%), 25–34 (558; 16.17%), 35–44 (681; 19.73%), 45–54 (619; 17.94%), 55–64 (509; 14.75%), and 65+ (643; 18.63%).

The respondents’ education was measured by using a categorical closed scale consisting of the following categories: primary education (168; 4.86%), apprenticeship (633; 19.21%), secondary education (1335; 38.68%), and tertiary education (1173; 33.99%).

The last socio-demographic factorial variable used in our research was the field of work or study, which was measured by using a categorical closed scale consisting of the following categories: management and control (199; 5.77%); technique and technology (381; 11.04%); medicine and health (265; 7.68%); education and training (506; 14. 66%), business and economics, including accounting (199; 5.77%); engineering and technology (381; 11.04%); medicine and health (385; 11.16%); public administration, including clerk/official (218; 6.32%); information and communication technology (117; 3.39%); legal, social, or cultural (269; 7.79%); auxiliary and unskilled labor (96; 2.78%); service sector (391; 11.33%); security forces (123; 3.56%); and agriculture and livestock (155; 4.49). A total of 33 (0.96%) respondents did not respond.

Another group of factorial variables consists of those that measure usage of and behavior on OSNs. The first of these variables showed us whether the respondent had an account(s) on a social network(s) (SNE). This was measured using a categorical scale consisting of two options: yes, I have an account (2699; 78.21%); no, I do not have an OSN account (752; 21.79%). The second variable used for measuring behavior on social networks was dedicated to the average time spent on each visit (SND). We set three distinct time intervals: short—up to 15 min (1517; 56.46%); between 15 and 30 min (674; 25.08%); and over 30 min (496; 18.46%). The third factorial categorical variables measured the frequency of visits to social network(s) (SNF). In this case, we distinct four frequencies: never (764; 22.14%), occasionally (824; 30.67%), daily (1000; 37.22%), and multiple times per day (863; 32.12%).

The last important question we asked to measure behavior on OSNs was about addictive smartphone usage (ASPU) for checking social network updates and status (including emailing and messaging). The respondents were asked if they feel inconvenience in situations when they cannot use their smartphones. According to previous research [13,80], we assumed the accessibility of smartphone for checking OSN updates and/or messages and (especially) the feeling of inconvenience when smartphones are not available could be considered to be the secondary variables for confirmation that social networking is unwittingly experienced as an escaping or shared liquid leisure activity. The inconvenience of not being able to use a smartphone to update social media and read emails/messages was measured on a categorical scale consisting of the following options: I always feel strongly inconvenienced without OSN updates (89; 2.58%); I often feel inconvenienced without OSN updates (230; 6.66%); Sometimes I feel inconvenienced, but I can live without OSN updates (1805; 52.30%); I never feel inconvenienced, and I do not use mobile data (282; 8.17%); I never feel inconvenienced, I often do not carry my cell phone (548; 15.88%); and I do not use a smartphone (497; 14.40%). The respondents who answered that they do not use smartphones were not included when hypotheses Hmc, Hc2, and Hc1 were tested.

The only measured variable was dependent-social networking as a leisure activity (SNL). This special variable was measured using The Catalogue of Leisure Activities (CaLA) [81,82], which was created for the quality classification of different activities. It is a tool for leisure research across generations, and it provides a systematic breakdown of leisure activities based on a decimal classification by content focus and allows for the aggregation of sub-activities into larger units. The catalogue currently contains 9 main categories, 77 sub-categories, and 285 leisure sub-activities. The possibility of aggregating activities into larger units makes the catalogue a suitable tool for conducting research surveys in which leisure is represented as the dependent or independent variable. The measured occurrences of each activity are complemented by three secondary variables that provide information on the frequency of the respondent’s leisure activity, the degree of its popularity, and the way it is organized.

Leisure activities that can be considered leisure on OSNs are part of category 900, entitled “Virtual reality and social activities in virtual worlds”, subcategory 960—OSNs [82]. From the total of 3451 respondents, only 221 (6.40%) marked social networking as a leisure activity. The remarkable difference between the number of social network users (2699; 78.21%) and the number of those who marked these activities as leisure inspired us to rethink the role of social networking in work, life, and leisure, which led us to reconceive our hypotheses concerning this role.

The reliability and validity of leisure measurements using the CaLA were widely discussed in our paper concerning the CaLA [81].

2.3. Hypotheses and Statistical Procedures

At the beginning of our research, the main hypothesis Hm was formulated as follows: There is a difference between SNE and SNL. To test this hypothesis, we used the χ2 test of good fit [77]. The validity of the null hypothesis in this case was based on the assumption that activities on OSNs are considered leisure and people who are active users of OSNs are also experiencing these activities as leisure. To test the main hypothesis Hm, we used two binomial variables: SNE, which indicates whether the respondent is an active user of OSNs, and SNL, which indicates whether the respondent recognizes and identifies activities on OSNs as leisure activities. For the testing of Hm, the expected values were loaded from the binomial variable SNE because the null hypothesis assumed the SNE and SNL were distributed equally. The observed values were loaded from binomial variable SNL.

To test the integrity of our theory, we measured the tendency for the addictive behavior of using smartphones and used it as a control variable to complementize the behavior of those who recognized social networking as leisure and those who did not. Therefore, a control hypothesis Hmc was formulated: There is an association between SNL and ASPU.

Subsequently, the following hypotheses that elaborate on the control function of Hmc and show the structure of OSN users in more detail were formulated:

Hypothesis C1 (Hc1):

There is an association between SND and ASPU.

Hypothesis C1 (Hc2):

There is an association between SNF and ASPU.

For additional three-dimensional analysis, the following four hypotheses were formulated and tested in our research:

Hypothesis 1g (H1g):

There is an association between SNL, SND, and G.

Hypothesis 1a (H1a):

There is an association between SNL, SND, and A.

Hypothesis 2g (H2g):

There is an association between SNL, SNF, and G.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a):

There is an association between SNL, SNF, and A.

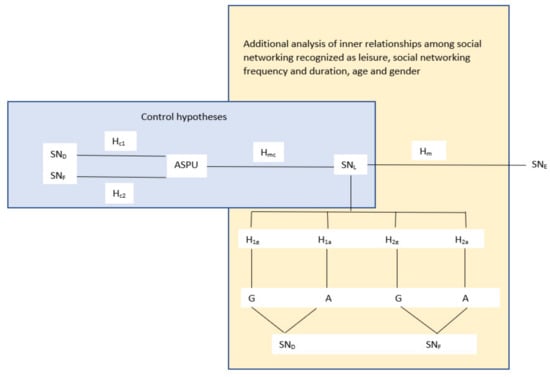

The system and relationships between hypotheses are illustrated in the Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schema of the conceptualization of hypotheses.

The statistical significance of hypotheses were tested using χ2 statistics and Pearson G2 statistics for two-way (C × R) and three-way (C × R × L) contingency tables, respectively [77,83]. For the better interpretation of the results, the adjusted residuals z in each cell were calculated. In the case of three-way tables, we used two calculations of z—one for the layer result (marked as L) and one for the three-way result. The degree of statistical dependence is expressed in tabled results by the asterisks (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). These variant calculations allowed us to extend the result interpretations and to discuss the influence of layer variable (marked as Layer in the tables) in more depth.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of OSN Users

In our research, we received data from 3451 respondents. Only 752 (21.79%) reported that they did not have or use an OSN account. Remarkably, only 221 (6.4%) reported networking as leisure. To better understand paper outcomes, we set socio-demographic hypotheses concerning the relationship between socio-demographic factors (age, gender, education, and field of work or study) as independent variables, and OSNs usage intensity, frequency, and recognition of social networking as leisure as dependent variables. We confirmed the dependence of OSN usage intensity on gender (p < 0.001); OSN usage frequency on gender (p < 0.001), age (p < 0.001), education (p < 0.001), and field of work or study (p < 0.001); and recognition of social networking as leisure on gender (p = 0.0025), age (p < 0.001), education (p < 0.001), and field of work or study (p < 0.001).

OSNs were often used intensively by 1969 (56.97%) users and occasionally or rarely by 733 (21.24%) users. The most used was Facebook (83%), which women used significantly more (z: 4.91 ***) than men, and the most frequent respondents of these networks were those with a university degree (z: 8.88 ***). The respondents also reported the usage of other OSNs with the following preferences: 1953 (72.36%) used Facebook Messenger, 1663 (61.62%) used WhatsApp, 1581 (58.58%) used YouTube, 1120 (41.5%) used Instagram, 520 (19.27%) used Pinterest, and 274 (10.15%) used Twitter. Less than 10% of respondents used other networks.

Women were more likely to refer to social networking as leisure (z: 3.02 **). People whose profession comprised operating machines did not consider social networking to be leisure (z: 2.65 **). In contrast, people employed in the legal, social, or cultural (z: 3.62 **); information and communication technology (z: 2.12 *); and education (z: 2.48 *) fields more often identified social networking as leisure. The tendency to consider social networking leisure was shown to decrease with growing age. Higher educated people considered social networking leisure more often (z: 3.80 ***) than those who achieved upper secondary education without direct access to tertiary education (z: 5.55 ***).

The usual frequency of visiting OSN sites (SNF) was daily or more (1863; 69.02%). Women, more than men, used OSNs once a day (z: 2.43 *) or more than once a day (z: 3.51 ***). Considering the respondents’ education, the most frequent users of OSNs were found to be university (z: 11.29 ***) and secondary school (z: 8.61 ***) students. Considering the field of study and work, the frequency of OSN use was highest among people working in the fields of law (z: 5.03***), education (z: 3.72 ***), and management and control (z: 4.59 ***). Regarding age, the younger respondents had a higher frequency of OSN use, e.g., 15–24 (z: 17.51 ***) and 25–34 (z: 13.39 ***).

3.2. Hypotheses Testing and Results

The good-fit-test (Table 1) strongly confirmed Hm (χ2 = 3558.669, df = 1, p < 0.001). This result allowed us to perform consequential analyses of both groups of OSN users: those who recognized these activities as leisure and those who did not. The detailed test results of hypotheses Hmc, Hc1, Hc2, H1g, H1a, H2g, and H2a can be found in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 1.

Hm hypothesis—the difference between SNE and SNL.

Table 2.

Relationship between social networking recognized as leisure and the inconvenience of not being able to use a smartphone to update social media and read emails/messages.

Table 3.

Relationship between average duration of a single period of social networking and the inconvenience of not being able to use a smartphone to update social media and read emails/messages.

Table 4.

Relationship between frequency of social networking and the inconvenience of not being able to use a smartphone to update social media and read emails/messages.

Table 5.

Relationship between perception of social networking as leisure, average duration of a single period of social networking, and gender.

Table 6.

Relationship between perception of social networking as leisure, average duration of a single period of social networking, and age.

Table 7.

Relationship between perception of social networking as leisure, frequency of social networking, and gender.

Table 8.

Relationship between perception of social networking as leisure, frequency of social networking, and age.

The main control hypothesis Hmc—“There is an association between SNL and ASPU”—was not confirmed: χ2(df = 4) = 5.7916, p = 0.215258, n = 2616 (Table 2). Therefore, the users of OSNs who recognize this activity as leisure were not connected with the possibly addictive behavior of using smartphones. Hence, we can say the specific leisure activity of ‘social networking’ does not involve the addictive behavior of using smartphones. On the contrary, the correlation between increasing frequency of OSNs use was generally found with the increasing inconvenience of not being able to check updates on smartphones.

The hypothesis Hc1—“There is an association between SND and ASPU”—was confirmed: χ2(df = 8) = 57.7871, p < 0.001, n = 2616 (Table 3). People who visited networks for over 30 min reported feelings of inconvenience (z: 5.11 ***).

The hypothesis Hc2—“There is an association between SNF and ASPU”—was confirmed: χ2(df = 8) = 206.6512, p < 0.001, n = 2616 (Table 4). People who visit networks more than once per day reported feelings of inconvenience (z: 7.04 ***).

The hypothesis H1g—“There is an association between SNL, SND, and G”—was confirmed: χ2(df = 7) = 18.8670, pχ2 = 0.0086, G2(df = 7) = 19.4937, pG2 = 0.0068, n = 2687 (Table 5). Men did not consider networking to be leisure if they reported visiting networks briefly, for up to 15 min (from: 4.06 **). Within the layers, we observed differences for respondents who did not consider networking to be leisure: men did not consider networking leisure if they reported visiting networks for a short period of up to 15 min (z(L): 2.72 **), and women did not consider networking leisure if they reported visiting networks for between 15 and 30 min (z(L): 2.15 *).

The hypothesis H1a—“There is an association between SNL, SND, and A”—was confirmed: χ2(df = 17) 90.3983, pχ2 < 0.001, G2(df = 17) = 89.6165, pG2 < 0.001, n = 2687 (Table 6). Young adults did not consider networking leisure if they reported visiting networks for over 30 min (z: 7.75 ***). In contrast, middle (z: 2.84 **) and older adults (z: 4.14 ***) did not consider networking leisure if they reported visiting networks for a short period of up to 15 min. Seniors did not consider networking leisure if they reported visiting networks between 15 and 30 min (z: 2.87 **).

The hypothesis H2g—“There is an association between SNL, SNF, and G”—was confirmed: χ2(df = 7) = 81.4000, pχ2 < 0.001, G2(df = 7) = 85.0454, pG2 < 0.001, n = 2687 (Table 7). Women considered networking leisure if they reported visiting more than once per day (z: 2.97 **). Within the layers, we observed differences for respondents who did not consider networking as leisure: while men did not consider networking to be leisure if they reported visiting networks occasionally (z(L): 4.09 ***), women did not consider networking to be leisure if they reported visiting networks more than once per day z(L): 2.34 *).

The hypothesis H2a—“There is an association between SNL, SNF and A”—was confirmed: χ2(df = 17) = 556.3326, pχ2 < 0.001, G2(df = 17) = 548.9166, pG2 < 0.001, n = 2687 (Table 8). Young (z: 14.69 ***) and middle (z: 4.33 ***) adults did not consider networking to be leisure if they reported visiting networks more than once per day. In contrast, older adults (z: 13.80 ***) and seniors (z: 20.87 ***) did not consider networking to be leisure if they reported visiting networking occasionally.

4. Discussion

Testing our main and control hypotheses (Hm and Hmc, respectively) confirmed our theoretical assumptions concerning the different characteristics of leisure on OSNs. The results suggest that social media activity is a specific type of leisure that is fluid and not bounded by time or space. Moreover, it is often intertwined with other activities. In this paper, using the example of OSNs, we tried to conceptualize this specific type of leisure that is manifested by blurred borders.

Testing Hc1 showed that people who spend more than 30 min on OSNs a day feel inconvenienced when not able to check their OSNs or emails. The results of the Hc2 can be similarly interpreted. Here, the same discomfort was shown in people who spend visited OSNs more than once a day. Yang et al. [80,84] highlighted that pleasurable experiences and the habitual use of OSNs can lead to high levels of addiction. Moreover, the presence of OSNs on mobile apps can be used to predict smartphone dependency [80].

H1g confirmed an association between gender, the average duration of a single period of social networking, and the perception of social networking as leisure. A separate gender analysis of relationships between duration and the perception of social networking as leisure showed that in this analysis, women did not perceive duration as a factor that influenced the perception of social networking as leisure. In contrast, a separate analysis of men’s attitudes showed that they considered networking to be leisure only when they spent between 15 and 30 min on these networks. They did not reconsider it to be leisure when the duration was shorter. These results seem to confirm our assumption that a shorter duration of social networking indicates either social networking as a part of work or simply an escape from work; it is an opportunity to take a short rest that does not meet the criteria of leisure for these respondents.

H2g was also confirmed, and the association between gender, frequency of social networking, and perception of social networking as leisure was proven. A detailed analysis showed that increasing frequency indicated the tendency to recognize social networking as leisure for both men and women. There was no significant relationship between frequency of use and the perception of social networking as leisure in the case of the daily (once per day) use of OSNs.

In contrast to some other studies [48], we found that women used OSNs more frequently than men. In addition, Karatsoli et al. [49] showed that women prefer and use text messaging, social media, and online video chatting more frequently than men. Our findings concerning women could partly confirm the findings of Ho and Cho [50] that new mothers tend to consider networking as both personal and family leisure. Unlike women, men tended not to consider social networking to be leisure. We presume that for men, OSNs could be more often seen as a part of the work process. Men may also consider that OSNs can be used to build personal brands. Moreover, people who intensively use OSNs can be attractive to employers [85] who are seeking people for positions in management and leadership, business and economics, or information and communication technologies. Unfortunately, these jobs are usually filled by men [86]. This assumption could also be supported by the work of Bartosik-Purgat and Jankovska [87], who reported that Chinese men posted information about their achievements on OSNs more than Chinese women, who more often searched for job offers through OSNs. However, Unger et al. [88] found that employees shifted their time resources to their personal lives to improve their relationships. Moqbel, Nevo, and Kock [89] found that the intensive use of social networking at work could help to balance work, home, and leisure time, thus increasing employee job satisfaction. In this way, employees can balance many hours spent at work and social relationships via social networking.

The need for different contacts and the diversity of environments that largely determine their behavior is crucial for the discussion of H1a and H2a, as this behavior manifests itself in different ways due to the age of the respondents. The H1a and H2a results showed that young people often use OSNs and spend a long time on them. We believe this demonstrates the tendency and strong need for young people to interact with peers, communicate, and share emotions and content with the community [90]. A second reason may be the opportunity to meet people from diverse backgrounds. This need is so strong that they fulfill it even when they cannot meet in person, and the easy availability of online OSNs helps them achieve this need [91]. However, this can then lead to a narrowing of social contacts to the online environment, which carries considerable risks (e.g., [92,93,94]).

The people of the middle generation have grown up and lived differently from the people of the young generation. They, therefore, meet their needs for social contact in other ways [95]. In contrast to the young, who spend almost all their time with a relatively stable group of adults and their peers, adults regularly meet more heterogeneous groups of people and have more varied social contact at work or in their private lives. They often meet people of different ages, from different environments, with different opinions and attitudes, etc. In addition, social attachments have been shown to improve mental health across age groups [96,97].

Similarly, older adults can fulfil their need for social contact from in another way—direct contact, which could be a guide to understanding their quite negative attitude toward OSNs [95,98] as leisure.

According to these previous analyses, we can describe the conditions when time spent on OSNs is recognized as leisure: high intensity and frequency of use in 15–30 min periods. However, our starting question was whether occasional online activities, usually shorter than 15 min, are considered a kind of leisure. We believe these activities meet almost meet all of criteria of leisure (an unforced activity that is set in a particular context and that is realized in subjective or objective free time, performed using people’s resources and abilities, brings pleasure in anticipation or memory, and provides opportunities for recreation, personal growth, and service to others [18,19]). The only unmet criterion is the recognition of this activity as leisure.

Many researchers have debated the false duality of work and leisure [99,100], which supposes that work and leisure are polar opposites; what is work cannot be leisure and what is leisure cannot be work. Beatty and Torber [99] suggested that work and leisure share key characteristics and could exist simultaneously. Communication technologies such as mobile/smart phones are blurring the boundaries between work and family life [101]. In the same way, our research suggests that the borders between work and leisure in the case of networking are fluid. The idea of fluid borders is related to Bauman’s concept of the liquid modernity [58]. Liquids move easily; unlike solids, they are not easily stopped because they flow around obstacles in their path, dissolve or carry others away with them, and allow others to seep through them. The extraordinary mobility of fluids is what links them to the idea of “lightness”. We believe that this consistency to Bauman’s concept could be useful in study of the conceptualization of leisure, as also considered by Blackshaw [57].

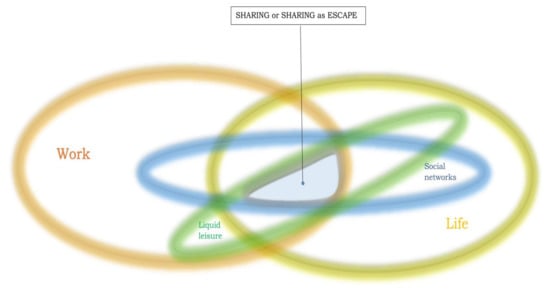

The idea of blurring the boundaries between work, life, and leisure as a starting concept for OSN use is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schema of the use of OSNs as liquid leisure.

Social networking permeates all areas of human life, both public and private. Due to the development of modern information technology in today’s postmodern society, networking is becoming an integral part of work. In some professions, networking can even comprise a major part of the working day. In personal life, networking helps one stay connected with friends and relatives near and far. In extreme cases, it can represent a form of the saturation of social ties. Networking can be considered to be a leisure activity when OSNs are used for the purpose of relaxation within life, as there are situations where information gained on OSNs in the context of work is transferable as enriching to life. The specific area we would like to highlight is the intersection of all three areas, i.e., work, life, and leisure. This intersection can take two forms: escape and/or sharing. Sharing in the intersection of work, life, and leisure is a classic case of multitasking. It can have positive effects for both work and life. However, it can also take the form of escape. Escape is a situation where someone escapes their workload; in a sense, it is a way for them to relax. Escape is typical for situations where work requires long, demanding, and intellectual concentration or represents a high stress load. Escape has several negative effects, such as impaired or lost concentration, procrastination, and the inability to understand/grasp a work task well.

5. Conclusions

Our research suggests that the borders between work, life, and leisure are fluid, and networking could be recognized as an example of liquid leisure. Although we have demonstrated the existence of liquid leisure in the case of social networking, it seems evident that it is not the only activity with similar attributes. This kind of leisure provides the same experience and satisfaction as any other kinds of leisure, but there are no obvious borders between it and other work or life systems. Liquid leisure can be subconsciously experienced, and the person experiencing it may not even be able to recognize that they are experiencing leisure. Except for the exact identification of this kind of time, all other criteria of leisure are met.

6. Limitation of Study

The results of this study are limited in several ways. The results are only valid for the population of The Czech Republic. However, we assume the relationship confirmed by the main hypothesis is strong enough that the results could be generally considered. There could also be several limitations regarding the reliability of the provided measurement. The concept of liquid leisure was only defined regarding social networking, and it should be considered in the future across the broad range of leisure activities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.O. and J.P.; methodology, J.P. and I.O.; software, J.P.; validation, J.P., I.O. and L.T.; formal analysis, I.O. and J.P.; investigation, J.P. and H.P.; resources, L.T. and H.P.; data curation, I.O. and J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.O., L.T. and J.P.; writing—review and editing, H.P.; visualization, I.O.; supervision, J.P.; project administration, H.P.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Palacký University, Olomouc, IGA_CMTF_2022_005. Values context of social functioning II.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to informed consent obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tkáčová, H.; Pavlíková, M.; Jenisová, Z.; Maturkanič, P.; Králik, R. Social Media and Students’ Wellbeing: An Empirical Analysis during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.J.; Widdop, P.; Cockayne, D.; Parnell, D. Prosumption, Networks and Value during a Global Pandemic: Lockdown Leisure and COVID-19. Leis. Sci. 2021, 43, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide as of January 2022, Ranked by Number of Monthly Active Users. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Allen, M.S.; Walter, E.E.; Swann, C. Sedentary Behaviour and Risk of Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 242, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Hoque, N.; Alif, S.M.; Salehin, M.; Islam, S.M.S.; Banik, B.; Sharif, A.; Nazim, N.B.; Sultana, F.; Cross, W. Factors Associated with Psychological Distress, Fear and Coping Strategies during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia. Global Health 2020, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, A.; Lodha, P. Social Connectedness, Excessive Screen Time During COVID-19 and Mental Health: A Review of Current Evidence. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Lopez-Fernandez, O. Internet Addiction and Problematic Internet Use: A Systematic Review of Clinical Research. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.M.; Soroush, A.; Khatony, A. The Relationship between Social Networking Addiction and Academic Performance in Iranian Students of Medical Sciences: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychology 2019, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Gong, M.; Yu, L.; Dai, B. Exploring the Mechanism of Social Media Addiction: An Empirical Study from WeChat Users. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1305–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Online Social Networking and Addiction—A Review of the Psychological Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3528–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. A ‘Components’ Model of Addiction within a Biopsychosocial Framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A.; Reinecke, L.; Meltzer, C.E. “Facebocrastination”? Predictors of Using Facebook for Procrastination and Its Effects on Students’ Well-Being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M. Using Social Networking Sites (SNS): Mediating Role of Self-Disclosure and Effect on Well-Being. Ir. Med. J. 2014, 6, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nimrod, G.; Adoni, H. Conceptualizing E-Leisure. Loisir Société Soc. Leis. 2012, 35, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sintas, J.; Rojas-DeFrancisco, L.; García-Álvarez, E. Home-Based Digital Leisure: Doing the Same Leisure Activities, but Digital. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 1309741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiotsalitis, K.; Stathopoulos, A. Demand-Responsive Public Transportation Re-Scheduling for Adjusting to the Joint Leisure Activity Demand. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2016, 5, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako-Tuffour, J.; Martínez-Espiñeira, R. Leisure and the Net Opportunity Cost of Travel Time in Recreation Demand Analysis: An Application to Gros Morne National Park. J. Appl. Econ. 2012, 15, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, R.A. The Idea of Leisure: First Principles; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, Canada, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4128-4272-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, M. Leisure: Theory and Policy; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1975; ISBN 978-0-398-04551-7. [Google Scholar]

- Neulinger, J. Value Implications of Denotations of Leisure. In Values of Leisure and Trends in Leisure Services; Venture: State College, PA, USA, 1983; pp. 19–29. ISBN 978-0-910251-05-1. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 978-94-017-9087-1. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper Perennial Modern Classics: New York, NY, USA; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-06-133920-2. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, T.P.; Hoffman, D.L.; Yung, Y.-F. Measuring the Customer Experience in Online Environments: A Structural Modeling Approach. Mark. Sci. 2000, 19, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Huang, W.-S.; Yang, C.-T.; Chiang, M.-J. Work–Leisure Conflict and Its Associations with Well-Being: The Roles of Social Support, Leisure Participation and Job Burnout. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkuba, M.; Hermenau, K.; Hecker, T. The Association of Maltreatment and Socially Deviant Behavior––Findings from a National Study with Adolescent Students and Their Parents. Ment. Health Prev. 2019, 13, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-J.; Wray, L.; Lin, Y. Social Relationships, Leisure Activity, and Health in Older Adults. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.S.; McKeown, J.K.L. Introduction to the Special Issue: Toward “Digital Leisure Studies”. Leis. Sci. 2018, 40, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallistl, V.; Nimrod, G. Media-Based Leisure and Wellbeing: A Study of Older Internet Users. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, M.; Millington, B.; Rich, E.; Bush, A. (Re-)Thinking Digital Leisure. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, G.; Ivan, L. The Dual Roles Technology Plays in Leisure: Insights from a Study of Grandmothers. Leis. Sci. Sept. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layland, E.K.; Peets, J.O.; Hodge, C.J.; Glaza, M. Sibling Relationship Quality in the Context of Digital Leisure and Geographic Distance for College-Attending Emerging Adults. J. Leis. Res. 2021, 52, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebblethwaite, S. Grandparents’ Reflections on Family Leisure: “It Keeps a Family Together”. J. Leis. Res. 2016, 48, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-R.R.; Schulz, P.J. The Effect of Information Communication Technology Interventions on Reducing Social Isolation in the Elderly: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Kong, S.; Jung, D. Computer and Internet Interventions for Loneliness and Depression in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2012, 18, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damant, J.; Knapp, M.; Freddolino, P.; Lombard, D. Effects of Digital Engagement on the Quality of Life of Older People. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 1679–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, A.K.; Nordmyr, J. Psychosocial Links Between Internet Use and Mental Health in Later Life: A Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2017, 36, 1471–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.E.; O’Brien, M.A.; Rogers, W.A.; Charness, N. Diffusion of Technology: Frequency of Use for Younger and Older Adults. Ageing Int. 2011, 36, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genoe, R.; Kulczycki, C.; Marston, H.; Freeman, S.; Musselwhite, C.; Rutherford, H. E-Leisure and Older Adults: Findings from an International Exploratory Study. Ther. Recreat. J. 2018, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiribuca, D.; Teodorescu, A. Digital Leisure in Later Life: Facebook Use among Romanian Senior Citizens. Rev. De Cercet. Si Interv. Soc. 2020, 69, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.V.; Noel, J.A.; Kaspar, K. Alone Together: Computer-Mediated Communication in Leisure Time During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosma, A.; Pavelka, J.; Badura, P. Leisure Time Use and Adolescent Mental Well-Being: Insights from the COVID-19 Czech Spring Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, G. Older Audiences in the Digital Media Environment. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, S.; Oinas, T.; Karhinen, J. Heterogeneity of Traditional and Digital Media Use among Older Adults: A Six-Country Comparison. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, D.; Leaman, C.; Tramposch, R.; Osborne, C.; Liss, M. Extraversion, Neuroticism, Attachment Style and Fear of Missing out as Predictors of Social Media Use and Addiction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S.J.; Charness, N.; Fisk, A.D.; Hertzog, C.; Nair, S.N.; Rogers, W.A.; Sharit, J. Factors Predicting the Use of Technology: Findings from the Center for Research and Education on Aging and Technology Enhancement (Create). Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, J.-L. Adult Attachment Orientations and Social Networking Site Addiction: The Mediating Effects of Online Social Support and the Fear of Missing Out. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshalawi, A.S. Social Media Usage Intensity and Academic Performance among Undergraduate Students in Saudi Arabia. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2022, 14, ep361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnjadat, R.; Hmaidi, M.M.; Samha, T.E.; Kilani, M.M.; Hasswan, A.M. Gender Variations in Social Media Usage and Academic Performance among the Students of University of Sharjah. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2019, 14, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatsoli, M.; Nathanail, E. Examining Gender Differences of Social Media Use for Activity Planning and Travel Choices. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2020, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-H.; Cho, Y.-H. Social Media as a Pathway to Leisure: Digital Leisure Culture among New Mothers with Young Children in Taiwan. Leis. Sci. Nov. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Chang, S.-Y.; Lien, W.-H. Work-Leisure Balance: Perceived Organizational Leisure Support. J. Leis. Res. 2021, 52, 202–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1990; ISBN 0-8047-1762-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dudová, R. Souvislosti Proměn Pracovního Trhu a Soukromého, Rodinného a Partnerského Života; Dudová, R., Ed.; Sociologický Ústav Akademie věd České Republiky: Prague, Czech Republic, 2007; ISBN 978-80-7330-119-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, G. Is Time a Problem? The Work-Life-Leisure Balance and Its Impact on Physical Activities: A Case Study in Denmark. Staps 2011, 94, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Bradley, L.; Lingard, H.; Townsend, K.; Ling, S. Labouring for Leisure? Achieving Work-Life Balance through Compressed Working Weeks. Ann. Leis. Res. 2011, 14, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wepfer, A.G.; Brauchli, R.; Jenny, G.J.; Hämmig, O.; Bauer, G.F. The Experience of Work-Life Balance across Family-Life Stages in Switzerland: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire-Based Study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackshaw, T. Leisure; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-135-14677-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; ISBN 0-7456-2410-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwer, J.; van Leeuwen, M. The Meaning of Liquid Leisure. In Routledge Handbook of Leisure Studies; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-203-14050-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vasco González, M.; Goig Martínez, R.; García Pérez, M. Percepción de Los Educadores Sociales Sobre El Ocio Digital Educativo Para La Inclusión de Los Jóvenes En Dificultad Social. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2020, 36, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parady, G.T.; Katayama, G.; Yamazaki, H.; Yamanami, T.; Takami, K.; Harata, N. Analysis of Social Networks, Social Interactions, and out-of-Home Leisure Activity Generation: Evidence from Japan. Transportation 2019, 46, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xue, S.; Shi, Y. Leisure Activities and Leisure Motivations of Chinese Residents. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, B.; Muffels, R. A Theory of Life Satisfaction Dynamics: Stability, Change and Volatility in 25-Year Life Trajectories in Germany. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 140, 837–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilka, G.C. Why Do Children and Adolescents Consume So Much Media? An Examination Based on Self-Determination Theory. Glob. Media J. 2018, 16, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, L.; Hoeber, O.; Snelgrove, R.; Hoeber, L. Computer Science Meets Digital Leisure: Multiple Perspectives on Social Media and ESport Collaborations. J. Leis. Res. 2019, 50, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athwal, N.; Istanbulluoglu, D.; McCormack, S.E. The Allure of Luxury Brands’ Social Media Activities: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Cirillo, C.; Diana, M. Activity Involvement and Time Spent on Computers for Leisure: An Econometric Analysis on the American Time Use Survey Dataset. Transportation 2018, 45, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H. In-Group and Out-Group Networks, Informal Social Activities, and Electoral Participation Among Immigrants in South Korea. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2017, 18, 1123–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, Q. Can Online Social Interaction Improve the Digital Finance Participation of Rural Households? China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlquist, E.; Prøitz, L.; Roen, K. Streams of Fun and Cringe: Talking about Snapchat as Mediated Affective Practice. Subjectivity 2019, 12, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Griffiths, M.D.; Yan, Z.; Xu, W. Can Watching Online Videos Be Addictive? A Qualitative Exploration of Online Video Watching among Chinese Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.I.; Ahmad, M. The Entrepreneur’s Quest: A Qualitative Inquiry into the Inspirations and Strategies for Startups in Pakistan. Pak. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2020, 58, 61–96. [Google Scholar]

- Limba, T.; Šidlauskas, A. Secure Personal Data Administration in the Social Networks: The Case of Voluntary Sharing of Personal Data on the Facebook. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2018, 5, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spottswood, E.L.; Hancock, J.T. Should I Share That? Prompting Social Norms That Influence Privacy Behaviors on a Social Networking Site. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2017, 22, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.; Foster, L.; Sloan, L.; Bryman, A. Bryman’s Social Research Methods, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-19-879605-3. [Google Scholar]

- Black, T.R. Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistics; Sage: London, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-0-7619-5353-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sheskin, D. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures, 5th ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-00-008327-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pospíšil, J. Social Survey Project; ITTS, s.r.o.: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Czech Statistical Office Vývoj Obyvatelstva České Republiky-2018. Available online: https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/vyvoj-obyvatelstva-ceske-republiky-2018 (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Salehan, M.; Negahban, A. Social Networking on Smartphones: When Mobile Phones Become Addictive. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2632–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, J.; Pospíšilová, H.; Trochtová, L. The Catalogue of Leisure Activities: A New Structured Values and Content Based Instrument for Leisure Research Usable for Social Development and Community Planning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, J.; Pospíšilová, H.; Trochtová, L.S. Catalogue of Leisure Activities. Available online: https://www.leisureresearch.eu/ (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Azen, R.; Walker, C.M. Categorical Data Analysis for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-367-35274-5. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Wang, B.; Lu, Y. Exploring the Dual Outcomes of Mobile Social Networking Service Enjoyment: The Roles of Social Self-Efficacy and Habit. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.; Rae, A. Building a Personal Brand through Social Networking. J. Bus. Strategy 2011, 32, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křížková, A. Životní Strategie Podnikatelek a Podnikatelů na Přelomu Tisíciletí; Sociologický Ústav Akademie věd České Republiky: Praha, Czech Republic, 2004; ISBN 978-80-7330-060-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosik-Purgat, M.; Jankowska, B. The Use of Social Networking Sites in Job Related Activities: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2017, 5, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, D.; Niessen, C.; Sonnentag, S.; Neff, A. A Question of Time: Daily Time Allocation between Work and Private Life. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqbel, M.; Nevo, S.; Kock, N. Organizational Members’ Use of Social Networking Sites and Job Performance: An Exploratory Study. Inf. Technol. People 2013, 26, 240–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, W. The Peer Interaction Process on Facebook: A Social Network Analysis of Learners’ Online Conversations. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 3177–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, E. Challenges for Meaningful Interpersonal Communication in a Digital Era. HTS Theol. Stud. 2019, 75, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, F.; Bellmore, A. Connecting Online and Offline Social Skills to Adolescents’ Peer Victimization and Psychological Adjustment. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.M.S.; Cheung, V.I.; Ku, L.; Hung, E.P.W. Psychological Risk Factors of Addiction to Social Networking Sites among Chinese Smartphone Users. J. Behav. Addict. 2013, 2, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.F.; Wachs, S. Adolescents’ Cyber Victimization: The Influence of Technologies, Gender, and Gender Stereotype Traits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.-J. Relationship Between Internet Behaviors and Social Engagement in Middle-Aged and Older Adults in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hämmig, O. Health Risks Associated with Social Isolation in General and in Young, Middle and Old Age. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Nonaka, K.; Kuraoka, M.; Murayama, Y.; Murayama, S.; Nemoto, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Matsunaga, H.; Fujita, K.; Murayama, H.; et al. Influence of “Face-to-Face Contact” and “Non-Face-to-Face Contact” on the Subsequent Decline in Self-Rated Health and Mental Health Status of Young, Middle-Aged, and Older Japanese Adults: A Two-Year Prospective Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, S.T.M.; Luijkx, K.G.; Rijnaard, M.D.; Nieboer, M.E.; van der Voort, C.S.; Aarts, S.; van Hoof, J.; Vrijhoef, H.J.M.; Wouters, E.J.M. Older Adults’ Reasons for Using Technology While Aging in Place. Gerontology 2016, 62, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, J.E.; Torbert, W.R. The False Duality of Work and Leisure. J. Manag. Inq. 2003, 12, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.A. False Dichotomies and Leisure Research. Leis. Stud. 2006, 25, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, D.; van Duin, D.; Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Smartphone Use and Work-Home Interference: The Moderating Role of Social Norms and Employee Work Engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).