Abstract

This study aimed to determine the compliance of management practices instituted in a third sector entity based on governance guidelines established by Brazilian organizations. It was exploratory qualitative research. Data were collected through in-depth interviews and documentary analysis; data analysis was performed by content analysis. The researched entity has a structure that meets the compliance function composed of three axes: (a) normative, referring to the adoption and formalization of the integrity program from instances, mechanisms and procedures dealing with ethical conduct, internal controls, laws, rules, regulations and risk management to which the entity is exposed, with complete adherence to the guidelines; (b) commercial, referring to the adoption and formalization of mechanisms covering relationships with partners, customers and suppliers, such as the accountability of funds raised; however, contingencies arising from the COVID-19 pandemic required mechanisms not yet foreseen for the accountability of resources from private donations. This axis had low adherence to the guidelines: (c) organizational, referring to the adherence and commitment of senior management to the policies instituted with a view to preserving the net worth, a financial sustainability and corporate social responsibility with almost complete adherence to the tested guidelines. In conclusion, organizations that depend on resources need an institutionalized compliance structure to ensure high levels of adherence, because as they become more reliable, they will receive more credibility and legitimacy. This study, based on the perceptions of managers, contributes to demonstrate the relevance of governance and the establishment of a culture of compliance in the third sector.

1. Introduction

The effectiveness and efficiency of business operations require good corporate governance practices and the modernization of top management [1]. According to Associação Brasileira de Bancos Internacionais (ABBI) and Federação Brasileira de Bancos (Febraban) [2] they highlight that compliance practices integrated with the other pillars of corporate governance “are going to align processes, ensure compliance with standards and procedures and, mainly, preserve the company’s image before the market” [2] (p. 4).

The emergence of corruption cases in Brazil motivated the creation of Anti-Corruption Law No. 12846/2013 [3], which provides for administrative and civil liability of legal entities for administrative misconduct and poor corporate governance practices, also affecting the third sector. According to Halbouni, Obeid and Garbou [4], the emergence of corruption cases indicates poor corporate governance practices.

Non-profit organizations around the world have been faced with a growing demand for greater transparency and accountability. An example is the fact that the entities’ financial reports are no longer an exception, but a rule. This demonstrates the concern existing with the quality of information for decision making brought by studies such as those by Bromley and Powell [5], Haack and Schoeneborn [6], Ko and Liu [7] and, consequently, with the legitimacy and reputational value of these entities [8,9,10,11,12].

In this logic, efforts have been directed towards creating a culture of compliance in the third sector and, thus, greater efficiency in the management practices adopted. Accordingly, Haack and Schoeneborn [6] add that the economic, political and social contexts are immersed in constant changes and that these transformations bring the need for mechanisms of prevention and regulation in the scenario of economic activities. These changes in the structural and managerial development of private and public companies also extend to third sector organizations that, in recent years, have undergone major changes in the structuring and management control [5,13]. Accordingly, Nawawi and Salin [14] stress that the implementation of internal controls plays a significant role in mitigating fraud in an organization.

For ABBI and Febraban [2] (p. 24), the “Compliance Officers”, as a tool for creating “internal control procedures, training people and monitoring, with the objective of helping business areas to have the effective supervision” has been adopted as a factor of protection and improvement of the reputational value of non-profit entities. The fact that they act as allies of the State in meeting public needs has diverse relationships and are subjected to the most diverse operational risks, which requires behavior guided by guidelines that seek compliance and contribute to their credibility and permanence [5,13].

Controllership and corporate governance models are needs of the third sector that expand and modify in the same proportion of the growth and importance that these entities represent for social development. Such changes demand improvement and scientific studies that contribute with quality indicators of the instituted practices and, in this context, indicate the status quo of the compliance culture in this sector [15]. It starts from the premise that the management of most philanthropic organizations is still precarious, giving rise to management models and controls, especially in fundraising and accountability [16,17].

The adoption of management practices, based on compliance guidelines, brings greater transparency, trust and seriousness to third sector entities [17]. These perceptions motivated this study and the formulation of the following research question: What is the compliance of management practices instituted in a third sector entity based on corporate governance guidelines established by Brazilian organizations—Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance (IBGC), the Comptroller General of the Federation (CGU) and the Brazilian Association of Fundraisers (ABCR)?

In view of the above problem, the general objective was to determine the compliance of management practices instituted in a third sector entity based on governance guidelines established by Brazilian organizations.

The integrity of management practices established in organizations, in particular in third sector entities, is considered to contribute to “mitigate” sanctions in cases of condemnation of organizations involved in corrupt or fraudulent practices. In this line of thought, it is hoped that this study will contribute to a greater understanding of the topic in question and to better prepare third sector entities and their leaders. The adoption of compliance practices and the establishment of a compliance culture in the third sector presents itself as a viable path to corporate social responsibility and organizational sustainability.

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Institutional Theory

Institutional theory has been used to analyze social phenomena (particularly organizational), and their constructs assist in the perception of “the social world as significantly composed of institutions that establish conditions for action” [18] (p. 1). Institutions are inserted in the social order and determine the flow of social life and actions. Deviations are automatically identified by social controls that make the infraction costly [18]. These controls are at the service of compliance, risk management, costs and increased legitimacy [18]. This point of view is also defended by Fachin and Mendonça [19] (p. 36) when they highlight, based on the evolution of institutional theory, that environmental pressures are considered to be “environmental forces, condition, organizational action in an effort to perpetuate itself, survive and, fundamentally, institutionalize”.

Based on these ideas, this study adopts the definition of institutionalism as “those repetitive social behaviors that are, to a greater or lesser extent, considered to be true, supported by normative systems and cognitive understandings that provide meanings for social exchanges and thus enable self-reproduction of the social order” [20] (pp. 4–5). In this line of thought, Scott [21] (p. 48) characterizes the institutions by saying that “they are composed of regulatory, normative and cultural-cognitive elements that, together with associated activities and resources, provide stability and meaning for social life”.

This statement highlights the influence of institutions in regulating the activities of individuals and organizations in view of the norms and standards of behavior to be followed. Accordingly, Meyer and Rowan [22] already warned that, in the face of environmental uncertainties, the competition of organizations turns both towards the search for resources and consumers, as well as the search for institutional legitimacy, making organizational practices increasingly homogeneous and isomorphic, thus resulting in less variety and institutional instability.

Coercive Pressures and Organizational Behavior

For Powell and DiMaggio [23], organizations need to comply with the social rules, norms and social values prevailing in their organizational field to obtain legitimacy. Under the logic of institutional isomorphism, DiMaggio and Powell [24] identify three types of institutional pressure: mimetic, coercive and normative, which can be used as a norm for non-profit organizations.

Similar to the resource-dependence theory, the new institutional theory applied to the third sector can explain the pressures of their environments in view of the perpetual search for resources. Andersson and Self [25] and Dey and Teasdale [26] defend the presence of commercial activity in the third sector and argue that the sustainability of these entities is increasingly linked to compliance with rules, norms and social values.

DiMaggio and Powell [24] highlight that organizations are shaped by the surrounding institutional environment, the growing changes and complexity of the external environment on isomorphic pressures. On coercive isomorphism, O’Rourke [27] states that it stems from legal and government sources. DiMaggio and Powell [24] (p. 150) assert that this “results from political influence and the problem of legitimacy. This fact also stems from pressures on the organization by other organizations on which the first depends”. Given that non-profit organizations depend on the government in terms of funding [28], government policies and decisions are mechanisms of coercive pressure. However, in addition to the government, other bodies act as sources of pressure, such as society, national and international bodies, companies, individuals, etc. [29]. Regarding mimetic isomorphism, DiMaggio and Powell [24] (p. 150) define it as “the process in which organizations deal with uncertainty or ambiguity in ‘copying’ other organizations, stems from standard responses to uncertainty”. In addition, O’Rourke [27] (p. 15) claims that mimetic isomorphism refers to “the adoption of best practices” by organizations in the same field in which they operate.

Thus, in the face of complex problems, an organization can model its response in line with organizations in the same field of activity perceived as “successful”, that is, copying similar organizations within their field of activity. For Subramony [30], this stems from organizations’ natural instinct to imitate each other as a heuristic device to find the most effective technological solution. The mimetic behavior of organizations in view of market pressures is explained by Neves and Gómez-Villegas [31] when they point out that organizations that operate in the same sector end up imitating each other due to pressures from the internal and external environment. They explain that the fundamental axis of institutional theory is the belief “that organizations that share the same environment will use similar practices and, therefore, will become isomorphic with each other” [31] (p. 17).

Regarding normative isomorphism, Suykens et al. [32] (p. 16) say that this arises from professionalization. Formal education and professional networks lead to a proliferation of insights, models and normative rules. For DiMaggio and Powell [24] (p. 15), these “epistemic communities” emerge mainly from normative isomorphism as a result of professionalization, where individuals or similar organizations come together and organize themselves to establish, promote and practice cognitive models to legitimize their activities. On professionalization in the third sector, Suykens et al. [32] (p. 16) say that normative isomorphism derives from cultural and professional expectations; they are, therefore, educational processes and that the “networks of professionals shape a particular logic of adequacy in professionals”. For these authors, entrepreneurial education can be treated as the development of business models, which increasingly, through courses in social entrepreneurship taught at universities, find space in the third sector.

For Aguiar and Silva [33], organizational studies based on institutional theory seek in sociology the concepts to consider organizations as systems, therefore subject to uncertainties, interdependencies and environmental pressures. The consideration and importance of cognitive systems and symbolic meaning for the study of organizations that the institutionalism approach took on, starting in the 1970s, Hoque [34] highlights that institutional theory involves qualitative methodology and has a focus on understanding specific accounting practices, a fact that allows the researcher to better understand the institutional sector, including how accounting practices are developed, experienced and/or abandoned. From the perspective, Bueno, Angonese and Gomes [35] accrescent that institutionalism has caused a break with the conventional way of thinking about the organizational structure, it requires consideration of the influence of the environment and the role of culture in the formation, improvement and similarity of organizations. Institutional theory has been used to explain accounting from a management perspective and “presents a different approach to studies on changes in management accounting” [36] (p. 8). Further, Burns and Scapens [37] (p. 1) emphasize that it is “from the institutional economy that the complex and continuous relationship between actions and institutions is explored, and demonstrates the importance of organizational routines and institutions in the formation of management processes of the accounting change”.

From the perspective that management practices adopted at the entity must respect the norms and direct it to degrees of production that ensure its survival, Guerreiro et al. [38] (p. 33) say that the institutional environment “is characterized by the elaboration of rules, practices, symbols, beliefs and normative requirements that individuals and organizations need to conform to in order to receive support and legitimacy”. This statement denotes the new perspective of the institutional environment brought by institutional theory. Its focus is on beliefs, rules and norms in the search for legitimacy, which affects the behavior of organizations. From this point of view, in the institutionalization process the values, beliefs, knowledge and actions are highlighted; this is a counterpoint to the classic theory of scientific administration permeated by the technical requirements of the execution of a task. In this sense, Fashola [39] highlights that the focus on beliefs, values and culture is opposed to the strictly rational and mechanistic view of the theory of scientific administration. The restructuring of organizations with the implementation of models of corporate governance and management control are attempts to improve their reputation and gain legitimacy. The culture of compliance within organizations requires alignment of organizational values, attitudes and beliefs with the principles of normative, organizational and commercial conformity.

2.2. Corporate Governance in the Third Sector

The third sector has an expressive participation in the economy, the activities performed fill government gaps or act “where the government cannot” [40] (p. 31), so the continuity of these organizations is extremely necessary. This sector has its own characteristics and, depending on its structure and performance, it operates with scarce resources from third parties [41]. Slomski et al. [42] explain this sector from the three-sector chain, in which each of the sectors plays a specific role in the economy based on its characteristics, namely: (a) in the first sector “there is the state and its political agents acting for public purposes”; (b) in the second sector “there is the market and its private agents acting for private purposes”; (c) in the third sector “there are private agents acting for public purposes” [42] (p. 4).

Third sector entities can operate in several areas; Olak and Nascimento [43] (pp. 23–24) say that “These organizations develop activities of a beneficent, philanthropic, charitable, religious, cultural, educational, scientific, artistic, literary, recreational, environmental protection, sporting nature, in addition to other services, always aiming at achieving social ends”. However, the social, economic and cultural changes that have emerged have demanded from this service area reinvention and new configuration based on principles of corporate governance and control and management tools. This need is due to the fact that these entities face challenges, among which sustainability stands out, mainly due to the dependence on resources, either by the government or by the private sector, from international organizations [44]. From this point of view, organizations that depend on government resources are under institutional pressure and are more inclined to act in accordance with the legislative apparatus to which they are exposed and to adopt internal and external regulations imposed on their activities [45]. The changes that have been implemented are due to changes resulting from laws, norms, as well as the creation of statutes and instruments that legalize and support donors and users of information, thus favoring and optimizing this sector of economy. In this context, institutional pressures cause the third sector to establish their own management models and adopt concepts and principles of management science. The State, as a regulatory agent, supports and encourages the development of the third sector based on norms and procedures, asserting its function of inspection, incentive and planning [8].

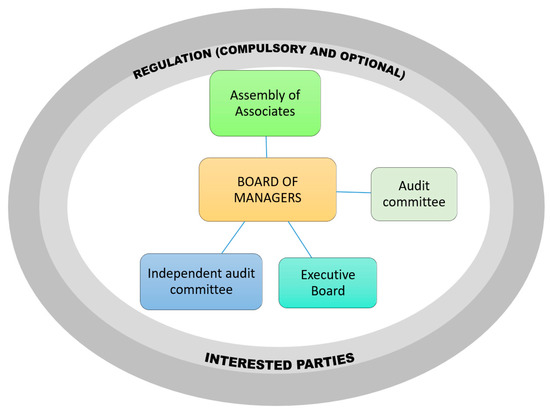

Governance is the “system by which companies are run, monitored and encouraged, involving the relationships between partners, the board of managers, the board of directors, supervisory and control bodies and other interested parties” [46] (p. 20). It should be noted that the legal institution of a private non-profit entity occurs through an association or foundation. This research was carried out in an association qualified by the Ministry of Justice as a social organization (SO). For Gomes [47] (p. 39), the qualification as SO is the process in which the public administration “grants a title to a private, non-profit entity, so that it can receive certain benefits from the Government (budget allocations, tax exemptions, etc.), to accomplish its purposes, which must necessarily be of interest to the community”. The governance structure of an association is usually composed of an assembly of associates, a board of managers, an audit committee, an executive board and an independent audit committee [46] (p. 19), as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Governance structure in the third sector. Source: Adapted from Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance (BICG) [46].

Figure 1 reveals that the institutional environment is governed by values, ethical conduct, legality, organizational compliance, enabling the “identification of vulnerabilities or risks for the legal entity” [48] (p. 72). The establishment of a culture of compliance in the third sector is a condition of sustainability, as it is a sector that depends on third-party resources, which allows the entities make the necessary efforts so that the activities they develop have high levels of compliance. Moreover, Colombo [49] states that philanthropic entities can use corporate governance, as do other sectors, to implement incentive and monitoring mechanisms, essential for achieving effective results.

For IBGC [50] (p. 20), good governance practices become “objectivity, alignment of interests that aim to preserve and optimize the entity’s long-term economic value” in such a way that they facilitate “access to resources and contributing to the quality of management, its longevity and the common good, they are: (a) transparency; (b) equity; (c) accountability; (d) corporate responsibility”. Explained as follows:

- (a)

- Transparency is the provision of information to interested parties “not just those imposed by provisions of laws or regulations”. In other words, it is necessary “not to be restricted to economic-financial performance, also considering the other factors (including intangibles) that guide management action and that lead to the preservation and optimization of the organization value” [50] (p. 20);

- (b)

- The principle of Accountability deals with the responsibility of corporate governance agents regarding the rendering of accounts “of their performance in a clear, concise, understandable and timely manner, fully assuming the consequences of their acts and omissions and acting with diligence and responsibility within the scope of their roles” [50] (p. 20). In accordance with these principles, the Brazilian Association of Fundraisers—ABCR [51]—has made efforts in favor of the quality of information and accountability from the third sector. The entity developed guidelines that guide philanthropic entities towards complying with norms, rules and instructions regarding the fundraising process. The Code of Ethics for the Fundraiser is a document that is available on the entity’s website, and its guidelines guide the conduct of people and the institution in the exercise of their activities, they are: 1st, Legality; 2nd, The remuneration of fundraising professionals; 3rd, Confidentiality and loyalty to donors; 4th, Transparency of information; 5th, Conflicts of interest; 6th, The donor’s rights; 7th, The relationship of the fundraiser with the organizations for which it mobilizes resources [51]. These guidelines were part of the data collection instruments of this research (interview script and document analysis), which can be better viewed in the results section.

- (c)

- Equity refers to the “fair and equal treatment of all partners and other interested parties (stakeholders), taking into account their rights, duties, needs, interests and expectations” [50] (p. 20).

- (d)

- Regarding Corporate Responsibility, it is important to note that governance agents must ensure the economic and financial viability of organizations, reduce the negative externalities of their businesses and operations and increase the positive ones, taking into account, in their business model, the various capitals (financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social, environmental, reputational, etc.) in the short-, medium- and long-terms [50] (p. 20). Management practices based on corporate governance criteria increase the entity’s social value and improve its performance.

According to Oliveira [52], it is from the maintenance of good practices and the foundation of actions that third sector entities perpetuate partnerships, covenants, donations and fundraising necessary for the maintenance and continuity of their social causes. This study is based on the corporate governance guidelines issued by the IBGC [50] (p. 13). These guidelines were part of the data collection instruments of this research (interview script and document analysis), which can be better viewed in the results section. Aiming at risk management, internal controls and conformity (compliance), the following guidelines were developed:

- (a)

- Actions related to risk management, internal controls and the conformity (compliance) system must be based on the use of ethical criteria reflected in the organization’s code of conduct;

- (b)

- The Board of Directors is responsible for approving specific policies for the establishment of acceptable limits for the organization’s exposure to these risks;

- (c)

- Compliance with external and internal laws, regulations and norms must be guaranteed by a process of monitoring conformity (compliance) of all activities of the organization;

- (d)

- Board of Directors and Board of Managers must develop a risk discussion agenda;

- (e)

- In addition to identifying risks, the board must be able to assess the probability of their occurrence and the consolidated financial exposure to these risks, including intangible aspects;

- (f)

- The Audit Committee, through the internal audit work plan, must verify and confirm the adherence by the Board to the risk and conformity policy (compliance) approved by the Board;

- (g)

- The Board of Directors, assisted by the control bodies linked to the Board of Directors (audit committee) and by the internal audit, must establish and operate an effective system of internal controls for monitoring operational and financial processes, including conformity (compliance);

- (h)

- The system of internal controls should not focus exclusively on monitoring past facts, but also include a prospective view in anticipating risks [50] (pp. 91–92).

According to these principles, the so-called governance agents are fundamental pieces for the development of good corporate governance practices in philanthropic entities. It is up to the manager of these entities to create conditions of continuity in the provision of social services, “in addition to seeking quality and timeliness that society requires” [40] (p. 145). For IBGC [50] (p. 91), corporate governance has the function of implementing and formalizing policies that ensure the conformity of the conduct and decisions of the entire organization. The conformity (compliance) system within the entity allows “the compliance with laws, regulations and external and internal norms, must be guaranteed by a process of monitoring conformity (compliance) of all the activities of the entity”. Accordingly, ABBI and Febraban [2] (p. 8) complement this, saying that “to be in compliance is to be in compliance with internal and external laws and regulations”. This means that the legislative apparatus to which third sector entities are submitted over time encompasses numerous actions, objectives and interests according to the needs of each entity.

2.3. Role of Internal Controls in the Management Process

The adoption and formalization of effective internal controls depends on the degree of knowledge of the manager regarding the particularities and needs of the entity. It is up to the manager to establish control mechanisms considering the integralities and externalities of the entity [53]. According to Slomski [40] (p. 15), it is necessary to build information systems that allow managers to monitor the performance of the entity’s activities, they must reflect the real needs and, thus, guidance on the best decisions so that they do not happen based on “guessing”. In this sense, knowledge of the management process of an entity requires the collection of information by internal controls (these are management mechanisms) so that they allow following “and criticizing the performance of activities, protecting assets, disciplining the relationship of the agents of execution with activities and guide the preparation of reliable information, is usually called control” [54] (p. 87).

The role of internal controls in third sector organizations is explained by the IBGC and the Group of Institutes, Foundations and Companies—GIFC [55]—when they say that the chief executive, assisted by the other control bodies linked to the Board, must monitor the fulfillment of the operational and financial processes, as well as the risks of non-compliance. It also suggests that the effectiveness of such systems be “reviewed at least annually”, and that “These systems of internal controls should also encourage the management bodies in charge of monitoring and inspecting to adopt a preventive, prospective and proactive attitude in minimizing and anticipating risks” [55] (p. 56). This statement demonstrates that internal controls subsidize decision making, knowledge of an entity’s management process and access to information by internal controls. The monitoring of activities within the entity aims to “protect assets, discipline the relationship between enforcement agents and activities and guide the preparation of reliable information, it is usually called control” [54] (p. 87). In this sense, internal controls are processes conducted by the structure of governance, management and other professionals of the entity whose purpose is “the identification of problems, failures and errors found through deviations, making the results obtained closer to the expected, verifying whether strategies and policies are generating the expected results and provide periodic information” [56] (p. 4).

In search of organizational integrity, Law 12,846/2013 [3], Anti-Corruption or Clean Record Law was instituted, which discusses the need to develop an integrity program, explained as a set of internal mechanisms and procedures for integrity, auditing and encouraging the reporting of irregularities and the effective application of codes of ethics and conduct, policies and guidelines with the aim of detecting and remedying deviations, fraud, irregularities and illegal acts practiced against the public administration. In view of the fulfillment of the legal framework, the Comptroller General of the Union [57] (pp. 6–25) elaborated five pillars explained in the Compliance and/or Integrity Program, namely: “1st Commitment and support from top management; 2nd Instance responsible for the Integrity Program; 3rd Analysis of profile and risks; 4th Structuring of rules and instruments; and 5th Strategies for continuous monitoring”. These guidelines were part of the data collection instruments of this research (interview script and document analysis), which can be better viewed in the results section.

These pillars, if followed and monitored, can guide conduct and practices in the entities, ensuring that the regulation, whether mandatory or not, is complied with. In search of compliance, Law 12846/2013 [3] imposes administrative and civil responsibilities on legal entities that come to practice illegal, fraudulent and corrupt acts in their own interest or benefit against the national or foreign public administration. According to CGU [57], it was from the Anti-Corruption Law that institutions began to take greater care in combating corruption due to “the possibility of taking severe sanctions within the scope of an administrative accountability process” [57] (p. 5).

2.4. Compliance Practices in Organizations

Compliance is “a set of rules, standards, ethical and legal procedures, once implemented, will be the guideline that will guide the institution’s behavior in the market in which it operates, as well as the attitude of their employees” [58] (p. 454). For Durães and Ribeiro [48] (p. 72), when well-structured and developed within an entity, compliance enables the “identification of vulnerabilities or risks for the legal entity”. Therefore, the compliance culture needs to be installed in organizations, the conformity function responds to institutional pressures and materializes with the creation and implementation of effective internal control mechanisms and risk management systems inherent to the management practices in the entity [59].

As one of the pillars of “Corporate Governance”, compliance is defined by the IBGC [50] (p. 20) as “a system by which companies and other organizations are managed, monitored and encouraged, involving the relationships between partners, the board of directors, management, inspection and control bodies and other interested parties”. Thus, “compliance is the process that investigates the application of internal policies and procedures, as well as laws, regulations, norms and agreements” [60] (p. 2), which can be established from three axes: the normative, the commercial and the organizational. The normative axis seeks to ensure compliance with rules, laws and norms to which the organization is subject. The commercial axis aims to meet the requirements of the business, covering commercial relations with partners, employees, customers and suppliers, etc. The organizational axis deals with organizational issues, driven by different factors such as the need to preserve the entity’s net worth to comply with corporate social responsibility. Responding to these needs is what makes compliance a critical concern for organizations. Therefore, it is “fundamental to understand, accept and follow the legislation” [60] (p. 2). Accordingly, Haes and Van Grembergen [45] say that compliance is also related to the duty to comply, be in compliance and apply internal and external regulations imposed on the entity’s activities. Clara et al. [61] (p. 225) add that “compliance means acting according to current rules and regulations”.

This research sought to adapt the management practices instituted by the studied entity in view of compliance guidelines in response to institutional pressures; the establishment of a compliance culture in the third sector is a condition of sustainability, as are the other organizations, as they suffer from external pressures because they depend on third party financing sources. In agreement, Verbruggen, Christiaens, and Milis [62] (p. 27) add that “when organizations understand that government subsidies, public or private donations depend on compliance, they will make the necessary efforts to reach maximum levels of compliance”.

2.5. Studies on Compliance in the Third Sector

Non-profit organizational behavior has been the subject of recent national and foreign research [9,48,49,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] that highlight integrity as a compliance principle of business ethics and corporate governance. Such investigations are based on institutional theory and resource dependence and have been used as theoretical structures to explain several aspects of organizational structure and performance. In this logic, studies [15,16,17,32,71,72] indicate that non-profit entities lack the adoption of good corporate governance practices in view of the achievement of their objectives and the fulfillment of their missions.

Lacruz [70] (p. 2) investigated the adoption and formalization of management practices based on corporate governance and concludes that the adoption of compliance practices makes these organizations “to be considered more attractive to donors and, consequently, receive more resources in donation”. For Senno et al. [68] (p. 225), compliance “is the principle of corporate governance that gives sustainability to relations, enabling and favoring that all stakeholders are respected”. In agreement, Candeloro, Rizzo and Pinho [58] (p. 454) define compliance as “a set of rules, standards, ethical and legal procedures, which, once defined and implemented, will be the main line that will guide the institution’s behavior in the market in which it operates, as well as the attitude of their employees”. According to Durães and Ribeiro [48] (p. 72), when well-structured and developed within an entity, compliance enables the “identification of vulnerabilities or risks for the legal entity”. Thus, in order to create efficient management mechanisms, effective internal controls and risk-management systems inherent to the management practice in organizations, it is necessary to adopt compliance guidelines.

In the same vein, governmental and non-governmental bodies, such as the Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance [50], the Comptroller General of the Federation [57] and the Brazilian Association of Fundraisers [51], have developed guidelines that encourage the effective use of management practices supported by compliance criteria, integrity program and adoption of principles of responsible and ethical performance. These bodies guide good practices, point out guidelines regarding the sustainable management of organizations, business improvement and improvements in the environment for fundraising.

According to Oliveira [52] (p. 13), integrity is set as “the shaping principle of business ethics and corporate governance” and without it “business ethics is broken and corporate governance is broken” [48] (p. 71). In this way, management and performance practices in the third sector demand a greater “level of professionalization of these institutions, enabling the adoption of corporate governance concepts and practices” [73] (p. 1). In the last few decades, third sector organizations have made considerable progress in generating their own resources, in fundraising from third parties and, therefore, in the development of management mechanisms [74]. Therefore, the increase in the volume of financial resources, public and private, as well as the need for measures of corporate responsibility have demanded a higher level of professionalism encompassed in corporate governance practices within these institutions [73], since fraud cases in this sector caused damage to the image and disbelief in the donor of resources [8].

In a scenario where third sector organizations leave a model of total dependence on third-party resources and start to generate their own resources, it is conducive to adopt management practices that helps them in this new performance dynamic [48]. In this study, we sought to understand the current scenario of the management of third sector entities, specifically to check how much the instituted practices are adhering to guidelines aimed at compliance. Although research [15,16,17,32,71,72] discuss management practices in the third sector, there are still few studies addressing the importance of the compliance culture in organizational sustainability in third sector entities, as well as meeting their social responsibility.

3. Research Methodology

This research aimed to determine the compliance of management practices instituted in a third sector entity based on governance guidelines established by Brazilian organizations. The understanding of how the entity structures the compliance function in response to institutional pressures is in line with the objectives of qualitative research of an exploratory nature given the need to “achieve insights and familiarity with the subject for further investigation” [75] (p. 24).

The research was limited to a social health organization (OSS). The study took place in its headquarters, located in the city of São Paulo. The cryptic was to working in the health area in several Brazilian states and municipalities; by and large, the entity has more than 50,000 employees, maintains active management agreements and contracts with the State Department of Health (SES), a sector that receives a considerable amount of public resources. The manager responsible for the controllership and accounting area was selected for interview. Data were collected through in-depth interviews and archival data. The interview script was prepared based on the study by Melo [8] (pp. 91–101), which used 20 compliance guidelines. Of these, 8 were proposed by IBGC [50] (pp. 91–92), 7 by ABCR [51] and 5 by CGU [57] (p. 7).

The research instrument consisted of 3 parts, totaling 23 questions; of these, 3 are structured and 20 are semi-structured, namely: (a) part I aimed to identify management practices linked to rules, norms and laws to which the entity is subject to (axis of normative compliance) based on themes and sub-themes such as fostering an ethical culture and disseminating laws and regulations, adoption of a manual of conduct, existence of cases of irregular practices and measures adopted, compliance sector practices, internal controls, mechanisms for monitoring and reviewing the instituted policies, management functions. This part of the script was composed of 9 questions covering the 9 compliance guidelines, and of these, 6 were proposed by IBGC [50] and 3 by CGU [57] described in Table 1; (c) part II aimed to identify management practices linked to the entity’s relationship with partners, customers, employees and suppliers (axis of commercial compliance) based on themes and sub-themes such as formalization of partnerships, existence of a donor bill of rights, employee remuneration, conflict of interest in the fundraising sector, confidentiality of donor information, disclosure of the destination of the funds raised, evaluation of the fundraising process. This part of the script is composed of 7 compliance guidelines proposed by ABCR [51] described in Table 2; (d) part III aimed to identify management practices related to corporate social responsibility and the need to preserve the company (axis of organizational compliance) based on themes and sub-themes such as harmful acts and fraud in the fundraising process, risks inherent to the activities carried out by the entity, policies that institute risk management, existence of an audit committee, etc. This part of the script is composed of 4 guidelines and their subcategories, proposed by ABCR [51], described in Table 3.

In order to validate the instrument and seek greater data reliability, a pre-test was carried out with a professor–researcher in the third sector area and with a researcher and consultant working in non-profit entities. After this stage, data collection started in September of 2020—this phase was subdivided into three stages: (a) pre-invitation; (b) invitation; (c) interview and signing the informed consent form. The interview took place via Skype, according to the employee’s availability and lasted 2 h and 10 min. It was transcribed and sent to the interviewee for consent, correction and validation.

The analysis of documents aimed at the triangulation of the data obtained in the interview. The documents analyzed were: (a) Manual of Administrative Compliance, Policies and Principles of Integrity; (b) Compliance and Integrity Report; (c) Financial reports for the 2018 financial year. The form prepared for the analysis of documents was based on the 20 compliance guidelines contained in the interview script and its application was based on a qualitative scale of Adherence to Guidelines (AG) of 5 points, where: 0—No Adherence to Guidelines (NAG); 1—Minimum Adherence to Guidelines (MAG); 2—Partial Adherence to Guidelines (PAG); 3—Satisfactory Adherence to Guidelines (SAG); 4—Almost Total Adherence to Guidelines (ATAG); 5—Total Adherence to Guidelines (TAG). For this classification, excerpts of the documents were identified that contained keywords and themes of each guideline in order to determine the adequacy of the established management practices; that is, topics of each compliance guideline were translated into policies and practices enunciated by the entity in each document, described in Table 4.

Table 4.

Adequacy of Management Practices to the Research Compliance Guidelines in document analysis.

Data were analyzed through content analysis according to Bardin [75] (pp. 125–131) and through the interpretation of meanings according to Gomes [76] (pp. 100–101), which proposes: “(a) to seek the internal logic of facts, reports and observations; (b) to situate facts, reports and observations in the context of the actors; (c) to produce an account of the facts in which its actors recognize themselves” [76] (pp. 91–92).

4. Results and Discussions

The results are derived from the interview data and the analysis of the archival data. Through the organization, tabulation and initial interpretation of the data, themes and sub-themes were identified, which were reorganized and reinterpreted. From these analysis and interpretation procedures, the following categories emerged: (a) adequacy of management practices regarding the normative compliance axis; (b) adequacy of management practices regarding the organizational compliance axis; (c) adequacy of management practices regarding the commercial compliance axis; (d) compliance of management practices according to archival data as follows.

4.1. Adequacy of Management Practices Regarding the Normative Compliance Axis

This part consists of nine guidelines, six of which were proposed by the IBGC [50] (pp. 91–92) and 3 by the CGU [57] (p. 7). As described in Table 1, this axis indicate that the researched entity has implemented policies and practices, such as: (a) dissemination of the ethical culture, laws, norms and regulations with the adoption based on a manual of conduct; (b) developed mechanisms for the identification of irregular practices and measures adopted; (c) created the compliance, internal controls and risk-management sector; (d) developed mechanisms for monitoring and evaluating the instituted policies; (e) counted on the support and commitment of the top management in the instituted policies and practices, as follows.

Table 1.

Normative Compliance Axis.

Table 1.

Normative Compliance Axis.

| Management Practices Instituted | Guidelines/Bodies/Interview/Document Analysis |

|---|---|

| Implementation and dissemination of laws, regulations and the adoption of the ethical conduct manual. | Guideline 01—IBGC—Actions related to risk management, internal controls and the compliance system must be based on the use of ethical criteria reflected in the organization’s code of conduct. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Adoption of mechanisms guiding irregular practices such as the application of sanctions and/or dismissals in cases that have occurred. | Guideline 02—IBGC—Procedures and measures to be adopted in cases of irregular practices and misconduct within the entity. |

| |

| “Almost Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—4 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Implementation of the compliance sector and the Integrity program. | Guideline 03—CGU—Practices and procedures adopted by the compliance sector or Integrity Program adopted by the entity. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| The adoption of internal controls by the entity’s compliance committee and supervisory bodies. | Guideline 04—IBGC—Functions and procedures of the internal controls adopted for risk management in the entity. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Monitoring and reviewing the instituted policies. | Guideline 05—CGU—Mechanisms for monitoring and reviewing policies instituted by the compliance sector or the Integrity Program. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Formulation of parameters for the instituted policies so that they do not put the entity at risk. | Guideline 06—IBGC—Formulation of parameters and monitoring of the management practices adopted and policies instituted by the entity. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Action by the Board regarding the policies instituted so that they do not put the entity at risk. | Guideline 07—IBGC—Development by the Board of policies that establish the entity exposure limits to general risks and in the fundraising process. |

| |

| “Almost Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—4 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Adherence and support from top management in fostering an ethical culture and dissemination of laws and regulations within the entity. | Guideline 08—CGU—Top management commitment to foster ethical culture and dissemination of laws and regulations within the entity. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Adoption and Formalization of corporate governance structures. | Guideline 09—IBGC—Role that is the responsibility of the management, the board and the internal audit sector in the entity. |

| |

| “Almost Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—4 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

Source: research data.

Data in Table 1 indicated that the Normative axis (legality) showed complete adherence to the guidelines the researched entity adopts and formalizes compliance practices in accordance with what the nine analyzed compliance guidelines propose. This is in line with Fashola [39], Slomski [40], Slomski et al. [42], Santos, Negrão and Saboya [44], and Haes and Van Grembergen [45], who emphasize that compliance practices are key elements for the achievement of reliability and legitimacy. With regard to the analysis of documents, the Almost Total Adherence to Guidelines (ATAG) adequacy of the management practices adopted in this compliance axis was found, with 42 out of the 45 points of the proposed scale representing a 93% disclosure.

Accordingly, Durães and Ribeiro [48] say that integrity is one of the structuring principles of business ethics and corporate governance. Maciel and Moura [12] also highlight efficiency, stability, reputation and their impacts on the fundraising process in non-profit organizations. According to these results, O’Rourke [27], Neves and Gómez-Villegas [31], Suykens et al. [32], and Bueno, Angonese and Gomes [35] explain the behavior of organizations from the perspective of institutional theory and highlight the market pressures and the tendency for companies to act according to the norm. In this logic, Andersson and Self [25] and Dey and Teasdale [26] conclude that the sustainability of non-profit entities is increasingly linked to compliance with rules, norms and social values. The role of internal controls in decision making is explained by Costa and Santos [53] and by IBGC and GIFE [55] as a way to monitor, inspect and predict risks. In Brazil, the compliance function is part of a legislative apparatus in response to the Brazilian commitment assumed before the international community to implement legal rules to fight corruption.

4.2. Adequacy of Management Practices Regarding the Commercial Compliance Axis

This part consists of seven guidelines proposed by ABCR [51], data obtained in this axis indicate that the researched entity adopts management practices such as: (a) establishment of partnerships; (b) employee remuneration policy; (c) mechanisms that allow transparency in the fundraising process and in the disclosure of the destination of the funds raised. However, it is still in the process of adopting and formalizing policies related to the fundraising process: (a) the donor bill of rights; (b) mechanisms to identify conflicts of interest; (c) mechanisms to maintain the confidentiality of donor information; (d) instruments for assessing the fundraising process. The data in Table 2 illustrate the brief summary of the findings on the business compliance axis.

Table 2.

Commercial Compliance Axis.

Table 2.

Commercial Compliance Axis.

| Management Practices Instituted | Diretrizes/Órgãos/Entrevista/Análise de Documentos |

|---|---|

| Implementation of the project sector with advice from the internal and external legal area to create partnerships with the public sector. | Guideline 10—ABCR—Formalization of the partnership process. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| The institutionalization of a Donor Bill of Rights or any other documentation was not identified. | Guideline 11—ABCR—Adherence to the Donor Bill of Rights. |

| |

| “No Evidence” of Compliance with this guideline—Score—0 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| No compensation policy for employees in the project area was identified. | Guideline 12—ABCR—Remuneration of employees in the project area. |

| |

| “No” adherence to this guideline—Score—0 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Procedures and measures to mitigate conflict of interest in the entity fundraising process. | Guideline 13—ABCR—Control of conflicts of interest in the entity fundraising process. |

| |

| “Almost Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—4 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Policy and mechanisms for protecting entity donor data. | Guideline 14—ABCR—Mechanisms adopted regarding the confidentiality of donor information. |

| |

| “Almost Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—4 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Accountability for the fundraising process. | Guideline 15—ABCR—Rendering of accounts of the destination of the funds raised. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| There are no specific mechanisms for evaluating the fundraising process. | Guideline 16—ABCR—Mechanisms for evaluating the fundraising process. |

| |

| “No” adherence to this guideline—Score—0 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

Source: research data.

Data in Table 2 indicated that the axis commercial compliance (relationships with partners, customers and suppliers) showed almost complete adherence to the guidelines. These results indicate that the researched entity seeks to act according to the norm, however there are still inadequacies and policies to be instituted, especially with regard to the process of raising funds from individuals, a process that has recently started at the entity. From the analysis of documents, a satisfactory 51% disclosure of the adequacy of management practices to the compliance guidelines of this commercial axis was identified, 18 out of the 35 points contemplated were obtained.

These results corroborate caveats by Santos, Negrão and Saboya [44], Valência, Queiruga and González-Benito [63], Hasnan et al. [64], and Charles and Kim [65] when they emphasize that organizational decision making needs to consider the entity’s reputation and sustainability. In agreement, Andersson and Self [25], Dey and Teasdale [26], and Veríssimo [59], say that the function of internal controls is to prevent, identifying acts of corruption, so that the sustainability of non-profit entities is increasingly linked to compliance with rules, norms and social values. Studies [44,77] emphasize that the fundraising process must be a well-planned activity within the entity. In agreement, Azevedo [9] and Dall’Agnol et al. [78] investigated remuneration policies for professionals in third sector entities and Lacruz et al. [69] focused on measures to address conflict of interest and donor rights.

Such studies defend the search for organizational integrity by complying with what the Anti-Corruption or Clean Record Law proposes, which discusses the need for the elaboration of an integrity program, explained as a set of internal integrity mechanisms and procedures with the objective of detect and remedy deviations, fraud, irregularities and illegal acts against the public administration.

4.3. Adequacy of Management Practices Regarding the Organizational Compliance Axis

This part is composed of four guidelines, three of which were proposed by the IBGC [50] (pp. 91–92) and one by the CGU [57] (p. 7), data on this axis indicate that the researched entity adopts the following management practices: (a) mechanisms to inhibit harmful acts and fraud in the fundraising process; (b) mitigation of risks inherent to the activities carried out; (c) risk management; (d) work of the external auditors. However, the adoption and formalization of an audit committee has not been identified. The following Table 3 data illustrate the brief summary of the findings on the organizational compliance axis.

Table 3.

Organizational Compliance Axis.

Table 3.

Organizational Compliance Axis.

| Management Practices Instituted | Diretrizes/Órgãos/Entrevista/Análise de Documentos |

|---|---|

| Forecasting and adopting risk prevention mechanisms that may threaten the assets. | Guideline 17—CGU—Forecasting mechanism for harmful acts and fraud in the fundraising process at the entity. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Mitigation and prevention of risks that may threaten the assets. | Guideline 18—IBGC—Risk mitigation and control mechanisms inherent to the entity activities. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Implementation of software and programs that help timely information that helps risk management and decision making. | Guideline 19—IBGC—Measures and strategies adopted, policies instituted, monitoring and validation regarding risk management in the entity. |

| |

| “Total” adherence to this guideline—Score—5 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

| Failure to adopt an audit committee at the entity because it has external audits and an internal audit area. | Guideline 20—IBGC—Existence of an Audit Committee and Internal Audit within the entity, their function and the implications and actions resulting from the opinions issued by these sectors in general and in the fundraising process. |

| |

| “Partial” adherence to this guideline—Score—2 (Analysis of documents, 2020). | |

Source: research data.

Data in Table 3 indicated that the axis organizational compliance (net worth and corporate social responsibility) had low adherence to the guidelines. These results demonstrate the behavior of the researched entity and its compliance structure with a view to mitigating risks that may threaten its continuity, as well as an available information system that helps in decision making. From the analysis of documents, it was found an 85% disclosure of the adequacy of the management practices instituted to the compliance guidelines in this axis, reaching 17 out of the 20 points of the scale.

These results are corroborated by authors such as França and Leismann [79] (p. 132) who, in relation to harmful acts, say that in “knowing and accepting the risks of each area it is possible to plan preventive acts”. Other studies [11,48,49,68] identified positive relationships between the audit committee, information symmetry and decision optimization. In agreement, the study by Azevedo [9], Valência, Queiruga and González-Benito [63], Hasnan et al. [64], Charles and Kim [65], Yeo, Chong and Carter [66], Hommerová and Severová [67] and Lacruz et al. [69] found that the increase in donation levels resulted from corporate governance, internal controls and compliance practices.

4.4. Compliance of Management Practices Established in a Third Sector: What Do the Documents Say?

Table 4 shows that the company studied is adequate (76%) to the 20 compliance guidelines of the study by the analysis of documents. The guidelines were defined with basis of practices recommended by the CGU; IBGC and ABCR. For this classification, the following qualitative scale was used: 0—No Evidence of Care (NEA); 1—Minimum Attendance Disclosure (EMA); 2—Partial Evidence of Care (EPA); 3—Satisfactory Evidence of Care (ESA); 4—Almost Total Evidence of Care (EQTA); 5—Total Attendance Disclosure (ETA), as follows.

According to data in Table 4, the Normative axis—legislation—showed complete adherence to the 9 governance guidelines, followed by the Commercial axis—relationship with third parties—which had low adherence to the 7 guidelines of the study and the Organizational axis—financial sustainability and social responsibility—with almost complete adherence to the 5 tested governance guidelines. Therefore, the Commercial axis is at greater risk for not meeting the good governance practices discussed in this work.

These results demonstrate the behavior of the researched entity and its compliance structure in view of risk mitigation that may threaten its continuity, as well as a timely information system that assists in decision making. According to research [16,17,32,71] highlight that the adoption of management practices, based on compliance guidelines, imprint greater transparency, trust and seriousness to third sector entities.

5. Conclusions

This research aimed to determine the compliance of management practices instituted in a third sector entity based on governance guidelines established by Brazilian organizations. We sought to identify how the entity is organized to respond to institutional pressures in order to preserve its image and reputational value. It was found that the management practices adopted proved to be adequate to the compliance guidelines proposed by the study. Such practices were classified based on three compliance axes, as follows:

- In the normative compliance axis (regulation and ethical conduct), the adoption of management practices was identified, such as: (a) implementation of the integrity program, ethical conduct, institutionalization of laws, norms and regulations; (b) implementation of the compliance sector, internal controls and risk management; (c) the creation of mechanisms to inhibit harmful acts and fraud in the fundraising process; (d) development of mechanisms for monitoring and evaluating the instituted policies. There was 93% adequacy of management practices adopted by the entity in line with the analyzed compliance guidelines, reaching 42 out of 45 points on the disclosure scale used in the analysis of documents on this axis.

- In the commercial compliance axis (relationship with third parties), the adoption of management practices was identified as: (a) establishment of public and private partnerships; (b) elaboration of the donor bill of rights; (c) establishment of an employee remuneration policy; (d) creation of mechanisms to identify and manage conflicts of interest in the fundraising process; (e) creation of mechanisms to maintain the confidentiality of donor information; (f) the creation of mechanisms that allow transparency in fundraising and in the dissemination of the destination of the funds raised; (g) elaboration of instruments for the evaluation of the fundraising process. It was possible to identify a 51% adequacy of management practices adopted by the entity to the analyzed compliance guidelines, reaching 18 out of the 35 points of the disclosure scale used in the analysis of documents of this axis.

- In the organizational compliance axis (protection of assets), it was possible to identify management practices, such as: (a) adherence and commitment by top management to the internal policies instituted; (b) implementation of a governance structure composed of a board of directors, a fiscal council, an audit committee, an executive board; (c) creation of control and risk management mechanisms inherent to the activities carried out; (d) implementation of an audit committee, the entity audited annually by an independent audit; (e) implementation of mechanisms and procedures for the transparency of information and accountability regarding the funds raised. It was possible to check an adequacy of 85% management practices adopted by the entity to the analyzed compliance guidelines, reaching 17 out of the 20 points of the disclosure scale used in the analysis of documents of this axis.

In accordance with these results, through the analysis of the documents, an adequacy of 76% management practices adopted by the entity was identified to the compliance guidelines used in this study, with the normative axis standing out with 93% adequacy of compliance with the guidelines. It is noteworthy that in this sector of the economy, the establishment of a compliance culture is an emergency, it is necessary to move towards management models and controls, especially in the processes of generation and fundraising. The third sector has been diversifying and growing over the years to the same extent and importance that it has for the development of the society. This change requires improvement and scientific studies that contribute with quality indicators of the instituted practices and, in this context, indicate the status quo of the compliance culture in this sector.

We infer that the conformity function contributes to the identification of vulnerabilities, to the mitigation of the entity’s exposure to risks and to the effective application of the resources destined to it; as they become more reliable, the information passed on in their reporting gains more credibility and legitimacy. It can be said, therefore, that organizations that depend on resources and understand that subsidies they receive, whether governmental, public or private donations, depend on an institutionalized compliance structure, will make the necessary efforts to ensure high levels of conformity.

Finally, this study, based on the perceptions of managers, contributes to demonstrate the relevance of governance and the adoption of compliance practices in the third sector. It also contributes to the adoption and improvement of management and control practices in the third sector, especially the awareness, on the part of management, about the importance of compliance for organizational sustainability and the achievement of corporate social responsibility.

Future research can better explore the “status quo” of the culture of compliance and corporate social responsibility established, through the compliance axes and guidelines established in this research. This will however, consider to a greater extent the number of organizations and diversity of areas of activity.

Author Contributions

Resources: V.G.S., A.A.d.B. and V.S.; Project administration; V.G.S. and V.S.; Conceptualization: V.G.S., A.A.d.B. and V.S.; Methodology: V.G.S., A.A.d.B., V.S., L.F.L. and A.L.F.d.S.V.; Writing-original draft: V.G.S., A.A.d.B. and V.S.; Data curation: V.G.S., A.A.d.B. and V.S.; Formal analysis: V.G.S., A.A.d.B., V.S. and L.F.L.; Visualization: V.G.S., A.A.d.B., V.S., L.F.L., A.L.F.d.S.V. and J.O.I.; Writing-review & editing: V.G.S., A.A.d.B., V.S., L.F.L., A.L.F.d.S.V. and J.O.I.; Validation: V.G.S., A.A.d.B., V.S., L.F.L., A.L.F.d.S.V. and J.O.I.; Funding acquisition: V.G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The translation of the text in English and the APC of this research was finalised by the Graduate Program in Accounting Sciences (GPAS) of the University Center of the Álvares Penteado School of Commerce Foundation–Unifecap.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meyer, V., Jr.; Pascucci, L.; Mangolin, L. Gestão estratégica: Um exame de práticas em universidades privadas. Rev. Adm. Pública 2012, 46, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associação Brasileira de Bancos Internacionais—ABBI. Federação Brasileira de Bancos. Febraban. Função de Compliance; São Paulo, 2009. Available online: http://www.abbi.com.br/download/funcaodecompliance_09.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Lei n. 12.846, de 1 de Agosto de 2013. Dispõe Sobre A Responsabilização Administrativa e Civil de Pessoas Jurídicas Pela Prática de Atos Contra A Administração Pública, Nacional ou Estrangeira, e dá Outras Providências. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2013/lei/l12846.htm (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Halbouni, S.S.; Obeid, N.; Garbou, A. Corporate governance and information technology in fraud prevention and detection: Evidence from the UAE. Manag. Audit. J. 2016, 31, 589–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, P.; Powell, W.W. From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 483–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haack, P.; Schoeneborn, D. Is decoupling becoming decoupled from institutional theory? A commentary on Wijen. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.W.; Liu, G. The transformation from traditional nonprofit organizations to social enterprises: An institutional entrepreneurship perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 25, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.C. Conformidade no Processo de Captação de Recursos pelas Organizações do Terceiro Setor; Dissertação de Mestrado; Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie: São Paulo, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, S.U. Disclosure e Influência Social na Captação de Recursos em Organizações Sem Fins Lucrativos; Tese de Doutorado; Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, N.L. Sustentabilidade organizacional no terceiro setor: Uma revisão sistemática no período de 2008 a 2018. Estud. E Pesqui. Avançadas Do Terc. Set. 2019, 6, 357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, M.; Gomes, M.J.F.; Zaramello, P.N.; Cruz, C.V.O.A. Arrecadação de Recursos das Entidades do Terceiro Setor na Região Sul do Brasil: Análise da Variável Contingencial Tecnologia. In Proceedings of the Anais do Congresso UFSC de Controladoria e Finanças, Santa Catarina, Brasil, 7–9 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maciel, V.D.S.; Moura, A.A.F. A Relação entre Eficiência, Estabilidade e Reputação na Captação e Geração de Recursos nas Instituições do terceiro Setor. Ph.D. Thesis, Fundação Instituto Capixaba de Pesquisas em Contabilidade, Economia e Finanças, FUCAPE, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wijen, F. Means versus ends in opaque institutional fields: Trading off compliance and achievement in sustainability standard adoption. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 302–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawawi, A.; Salin, A.S.A.P. Internal control and employees occupational fraud on expenditure claims. J. Financ. Crim. 2018, 253, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Reporting Council—FRC. Corporate Culture and the Role of Boards. 2016. Available online: https://www.frc.org.uk/Our-Work/Publications/Corporate-Governance/Corporate-Culture-and-the-Role-of-Boards-Report-o.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Nemoto, M.C.O.; Silva, D.A.; Pinochet, L.H.C. Avaliação de aplicações das boas práticas na gestão de projetos sociais para instituições do terceiro setor. Rev. Gestão Proj. 2018, 9, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.R.; Carvalho, J.S.; da Vieira, F.C. Gerenciamento além dos lucros: Controle contábil em uma entidade sem fins lucrativos. Rev. Gestão Em Análise 2018, 7, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.; Shadnam, M. Institutional theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication; Donsbach, W., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fachin, R.C.; Mendonça, J.R. Selznick: Uma visão da vida e da obra do precursor da perspectiva institucional na teoria organizacional. In Organizações, Instituições e Poder no Brasil; Vieira, M.M.F., Carvalho, C.A., Eds.; Editora FGV: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2003; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, R.; Oliver, C.; Lawrence, T.B.; Meyer, R. Introduction: Into the Fourth Decade. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Greenwood, R., Oliver, C., Lawrence, T.B., Meyer, R., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; DiMaggio, P.J. O Novo Institucionalismo na Análise Organizacional; Imprensa da Universidade de Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, F.O.; Self, W. The social-entrepreneurship advantage: An experimental study of social entrepreneurship and perceptions of nonprofit effectiveness. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2015, 26, 2718–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Teasdale, S. The tactical mimicry of social enterprise strategies: Acting ‘as if’ in the everyday life of third sector organizations. Organization 2016, 23, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, P.P. How NPM-inspired-change impacted work and HRM in the Irish voluntary sector in an era of austerity. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 42, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustinx, L.; Verschuere, B.; De Corte, J. Organisational hybridity in a post-corporatist welfare mix: The case of the third sector in Belgium. J. Soc. Policy 2014, 43, 390–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.E.G. Gestão, legislação e fontes de recursos no terceiro setor brasileiro: Uma perspectiva histórica. Rev. Adm. Pública 2010, 44, 1301–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramony, M. Why organizations adopt some human resource management practices and reject others: An exploration of rationales. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 45, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.R.; Gómez-Villegas, M. Reforma contábil do setor público na América Latina e comunidades epistêmicas: Uma abordagem institucional. Rev. Adm. Pública 2020, 54, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Suykens, B.; George, B.; Rynck, F.de; Verschuere, B. Determinants of non-profit commercialism. Resource deficits, institutional pressures, or organizational contingencies? Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 1456–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, A.C.; Silva, C.E.G. Avaliação de Atividades no Terceiro Setor de Belo Horizonte: Da Racionalidade subjacente às Influências Institucionais. Organ. Soc. 2011, 18, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, Z. Methodological Issues in Accounting Research; Spiramus Press Ltd.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, M.E.A.F.; Angonese, R.; de Gomes, D.G. Institucionalização de novas práticas de controles de gestão: Forças que potencializam ou comprometem o processo nos pequenos empreendimentos. Rev. Contemp. Contab. 2019, 16, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.T.; Parisi, C.; Pereira, C.A. Evidências das forças causais críticas dos processos de institucionalização e desinstitucionalização em artefatos da contabilidade gerencial. Rev. Contemp. Contab. 2016, 13, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Scapens, R.W. Conceptualizing management accounting change: In institutional framework. Manag. Account. Res. 2000, 11, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, R.; Frezatti, F.; Lopes, A.B.; Pereira, C.A. O entendimento da contabilidade gerencial sob a ótica da teoria institucional. Organ. E Soc. 2005, 12, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fashola, O.I. Banking and the customer: A neo-institutional reconfiguration. Res. J. Financ. Account. 2014, 5. Available online: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/RJFA/artic%20le/view/14807 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Slomski, V. Controladoria e Governança na Gestão Pública; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, H.M.B.; Rickardo, L.A. O papel da controladoria na gestão das entidades do terceiro setor. Revista Observatorio de la Economía Latinoamericana. n. 232. 2017. Available online: https://www.eumed.net/cursecon/ecolat/br/17/controladoria-brasil.htm (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Slomski, V.; Rezende, A.J.; Cruz, C.O.A.; Olak, P.A. Contabilidade do Terceiro Setor: Uma Abordagem Operacional: Aplicável às Associações, Fundações, Partidos Políticos e Organizações Religiosas; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Olak, P.A.; Nascimento, D.T. Contabilidade para Entidades Sem Fins Lucrativos (Terceiro Setor); Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Y.D.; Negrão, K.R.; Saboya, S.M. Estratégias para captação de recursos no terceiro setor: Um estudo multicaso aplicado na APAE Belém e APAE Barcarena. Rev. Adm. Contab.-RAC 2018, 5, 175–213. [Google Scholar]

- Haes, S.; Van Grembergen, W. Enterprise Governance of Information Technology. In Featuring COBIT5, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa—IBGC. Guia das Melhores Práticas para Organizações do Terceiro Setor: Associações e Fundações; Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, C.F. Atuação das organizações sociais de saúde no Estado de Pernambuco. Rev. Digit. Direito Adm. 2020, 7, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durães, C.N.; de Fátima Ribeiro, M. O compliance no Brasil e a responsabilidade empresarial no combate à corrupção. Rev. Direito Em Debate 2020, 29, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, F.N. Governança no Terceiro Setor: Uma Proposta de Prestação de Contas e Transparência Para uma Entidade Filantrópica de Criciúma; Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso; Universidade do Extremo Sul Catarinense: Santa Catarina, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa—IBGC. Código de Melhores Práticas de Governança Corporativa; Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Associação Brasileira de Captadores de Recursos—ABCR. Código de Ética e Padrões da Prática Profissional. 2020. Available online: https://captadores.org.br/codigo-de-etica/ (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- Oliveira, L.G.M. Compliance e Integridade Aspectos Práticos e Teóricos; D’Plácido: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- da Costa, A.R.A.; Santos, F.K.G. Os efeitos econômico-financeiros da controladoria para o desenvolvimento das empresas. Ideias Inovação-Lato Sensu 2020, 6, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Conselho Federal de Contabilidade—CFC. Manual de Procedimentos Contábeis para Fundações e Entidades de Interesse Social. 2007. Available online: https://www2.mppa.mp.br/sistemas/gcsubsites/upload/56/entidadesdeinteressesocialeterceirosetor-100819051041-phpapp01(1).pdf (accessed on 26 July 2020).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa—IBGC; Grupo de Institutos, Fundações e Empresas—GIFE. Guia das Melhores Práticas de Governança para Fundações e Institutos Empresariais. 2014. Available online: https://www.fbb.org.br/images/Documentos/Guia_das_Melhores_Prticas.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Lunkes, R.J. Controle de Gestão: Estratégico, Tático, Operacional, Interno e de Risco; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]