1. Introduction

Along with the gradual increase of uncertainties in the business environment, such as the China–US trade war, all walks of life worldwide generally suffered from industrial chain disruption, raw material price fluctuation and logistics cost rises, which leads to production and retailing plans invalidating and further results in the resource waste and inefficiency, especially for manufacturing enterprises and retailers. However, presale and other business strategies can reduce the waste of resources caused by improper production plan or excessive inventory, so as to improve the efficiency and sustainability. To this effect, considering the consumer strategic behavior’s impact on enterprises, formulating practicable and effective production and retailing plans is of key importance to all industry parties for sustain developing and enhancing efficiency purpose in these circumstances.

Among various effective commercial strategies for formulating production and retailing plan purposes, ascribing to its features of basing sales on production and providing refernce of the sustainable operation plan and implementation, the presale strategy has gained increasing popularity for enhancing company’ sustainability and efficiency in recent decades. For the presale strategy, it is a new product sales strategy in which a product or service starts accepting orders from customers before the official sale or typical sales season; that is, the target product of a new presale is a new product that will be available soon [

1]. The presale model was first used in the service industry, such as with airline tickets, tickets to tourist attractions, and hotel rooms. In recent years, it has been gradually applied to the retail industry with the popularity of online sales. The industry has also innovated various presale models according to different product characteristics and sales scenarios, such as the presale of new products [

2], the presale of customized products, and the presale of perishable products. However, the most widely used, most influential, and most influential online promotion presale models are initiated by sizeable online shopping platforms, such as Tmall, Jingdong, and Vipshop [

3,

4]. Take Tmall “Double 11” as an example, in 2018, the presale amount was 70.9 billion yuan, and the number of products participating in presale activities exceeded 500,000, including consumer electronics, apparel, beauty care, food, and wine, involving all aspects of clothing, food, housing, and transportation. Single products with transactions exceeding 10 million were about 100 models, which fully illustrates the success of the promotional presale models.

The presale model stretches consumers’ purchase time from one day to a week to a month, continuing to create a buzz and to repeatedly stimulate consumers’ potential purchase demand. The price of products in the presale stage is considerably lower than the price in the stock stage, and consumers only need to pay a small deposit to reserve products, which greatly reduces the purchase threshold of consumers and further induces consumers to spend. At the same time, the additional preferential strategies, such as “deposit expansion,” “full discount coupons,” and “limited-time gifts,” attached to the presale activities, further enhances consumers’ desire to purchase. E-commerce platforms can give full play to their platform advantages to pool traffic [

5] and can enhance advertising revenue. In detail, retailers can unify production and delivery according to orders after the presale ends, which reduces production, storage, and distribution costs to a certain extent; moreover, the demand data obtained from the presale stage can help retailers better plan an inventory for the spot period [

6,

7,

8]. Retailers decide whether to conduct presale, and determine the appropriate deposit ratio, pricing, and inventory arrangements in line with the expected valuation of consumers. Simultaneously, consumers can obtain larger discounts than usual purchase discounts and can acquire good value for their desired goods in a wide range of active categories. Considering consumers’ tendency to cancel or their return behavior, however, when the cancel rate or return rate is high, the sales volume and profit of the enterprise are bound to be affected, and the reduction is the main trend, which contradicts the main intention of presale strategies, and is facilitated by the sustainable operation plan and implementation of companies. At this time, businesses need to carefully study whether the products are worthy of presale or further continuous promotion in the market. Similarly, when considering the merchant’s presale strategy, a reasonable presale strategy can continuously stimulate the needs of consumers, maintain customer loyalty, continuously create new customer value and make the retailer operation plan sustainable.

A typical feature of the presale model is that consumer payment behavior occurs before the consumption behavior, and a certain time interval exists between the two. The separation of the consumer purchase behavior from the consumption behavior causes the generation of consumer valuation uncertainty. In service industry presales, consumer valuation uncertainty during the presale period stems mainly from uncertainty about the future state or the environment of their consumption [

9]. In retailing, consumer valuation uncertainty stems primarily to concern uncertainties relating to the attributes of new products [

10,

11,

12], as well as from a high or low comparison of the valuation achieved according to the receipt of the consumers [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Studies have focused on the premise that all consumer valuations influencing the post-purchase distribution is the same. However, Logunova et al. [

17] divided their customers into experienced and inexperienced customers. Nevertheless, no difference is observed between high and low valuation sizes. New products are more suitable for presale than old products due to the difference in the uncertainty of the valuation of goods [

18].

Researchers have also conducted a large number of studies around strategic consumer behavior in the field of presales, and scholars are currently discussing retailers’ optimal presale decision behavior mainly in a monopolistic setting. For example, Mersereau and Zhang [

19] studied the effect of strategic consumers on retailers’ price-reduction sales strategies when the total number of consumers is unknown. Aviv and Pazgal [

20] investigated how strategic consumers affect retailers’ optimal pricing and optimal profits when consumers’ valuation of a product is negatively related to market time. Moreover, Mao et al. [

21] assumed that all consumers are strategic consumers and comparatively analyzed the difference in a retailer’s optimal returns under a single presale strategy and a combined presale and buyback strategy. The linear demand diffusion effect was addressed based on the theory of anticipated utility in Xu et al. [

22] when assuming that short-sighted and strategic customers’ simultaneous market participation was considered. Lim and Tang [

23], in addition to classifying consumers as short-sighted and strategic, also included speculative consumers who aim to make a profit by reselling after purchase. Their results showed that strategic and theoretical consumers make the same purchase decisions regardless of whether the consumer valuation increases or decreases over time. Shu et al. [

24] distinguished from the above scholars and explored retailers’ presell strategies in a competitive environment by classifying consumers in the market into two categories.

Generally, on the one hand, existing presale studies have mentioned promotional presale models that have a profound effect on e-tailing. However, in practice, significant differences exist between promotional presale and new product presale in terms of the selection of target products and the sales process [

25,

26]. Moreover, systematically classifying and sorting out the characteristics of existing presale models are necessary to develop appropriate presale strategies for different presale models in terms of literature and retailers’ references of the sustainable implementation. On the other hand, the “deposit + final payment” sales model indicates that the retailers’ problem has changed from the optimal refund ratio to the optimal deposit ratio when consumers withdraw their orders, which is often the case in existing presale withdrawal-related studies. The present study incorporates new product presales and online promotional presales into the overall consumer behavior assessment while considering how different deposit ratio levels affect product yield and sales volume.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the literature review.

Section 3 provides the decision model for retailer nonparticipation in presales. We construct a decision model for retailer participation in presales in

Section 4 and then analyze and compare the different decision results in

Section 5. In

Section 6, numerical analyses are performed. Finally, we conclude our study in

Section 7.

2. Literature Review

The topic of this work falls in the design of the presale’s deposit and pricing of the product. Generally, the current research can be grouped into three categories: design decision and pricing of presale in supply chain contexts; deposit of presale when the consumer cancels the order; and how to decide to handle the deposit while the consumer is returning the product to the seller.

2.1. Presale and Pricing

Setting the best price to attain the most profit is a critical decision faced by every retailer, and the same is true in the presale field [

27]. On the basis of the relative size of spot sale period and presale price, presales can be divided into three modes: premium, discount, and equivalent presales. Particularly, premium presale refers to the mode where the presale price is higher than the regular sales period price, whereas discount presale is the opposite. Equivalent presale, as the name implies, refers to the presale mode in which the presale price is equal to the spot price [

28]. In real life, when customers obtain additional psychological satisfaction from buying goods in advance or the production of goods is limited, retailers often adopt a premium presale model. To attract more consumers to purchase in the presale stage, they tend to adopt the discount presale model.

After sorting out, the existing presale research, under different constraint conditions (e.g., diffusion effect, proportion of different types of consumer, and presale duration), mainly considers the corresponding retailers’ optimal ordering and pricing strategies. For example, Zeng [

13] believed that experienced consumers’ existence is why retailers implement premium presales. Nocke et al. [

29] separately analyzed consumers’ early purchase with or without discounts during the presale phase. They found that customers with high expectations of product value would buy when discounts are available for early purchase, whereas customers with a lower valuation of product value would choose to buy from stock. A series of academics have analyzed whether retailers should participate in presales and the applicable conditions corresponding to different degrees of discounts when participating in presales [

30,

31,

32]. Xie [

3] analyzed the capacity thresholds for the five cases of retailer nonparticipation in presales, discounted presales (with capacity limits), discounted presales (without capacity limits), premium presales (without capacity limits), and equal presales. Li [

33] also studied the effects of capacity restrictions on retailers’ presale strategies, who believe that whether consumers are willing to pay a presale price higher than the spot price for purchase depends on the consumers’ attitude. Zhou [

34] quantified the presale length and compared the retailers’ optimal profit with and without the presale volume limit. The results showed that the retailers can gain more profit with the presale volume limit.

Ji and Sun [

35] calculated the optimal profit when retailers adopt three strategies of no presale, discount presale, and premium presale. They also provided the optimal feasible domain under the corresponding strategies concerning price simultaneous existence effects, capacity constraints, and consumer heterogeneity. Zhai [

36] considered the effect of consumer search costs in addition to the uncertainty of consumer valuation. The results showed that only when the unit product cost meets certain conditions can the discount presale strategy be the best choice for retailers in the spot strategy. Wan et al. [

37] proposed a new price mechanism; that is, manufacturers do not disclose the specific price of the spot period during the presale period. Nevertheless, they assured consumers that the spot price is higher than the presale price. Numerical verification proved that this special price mechanism will significantly affect manufacturers’ decision making of production quantity, presale price, regular price, expected profit, and consumer behavior.

Some scholars have combined perishable products with presales. Zhao et al. [

38] considered the effects of consumers’ strategic buying behavior and product demand diffusion effects. They used prospect theory and expectation effect theory to study the premium presale problem of perishable goods. Although the focus of the two theories is different, the optimal presale prices calculated do not differ considerably. Some scholars have focused on the influence of retailer repurchase strategy in the context of discounted presales of perishable products, whereas some have focused on the effect of product substitution on retailers’ pricing decisions [

21,

39].

Although scholars have numerous entry points, they have mainly focused on addressing the questions of whether retailers should participate in presales, whether they should take premium or discount presales when participating in presales, and the corresponding degree of discounts. In this study, we focus on promotional presales, and as the name implies, we will take discount presales as the premise to demonstrate how the size of the deposit ratio affects retailers’ optimal presale price.

2.2. Presale Deposit and Cancellation

After sorting through the studies, we find that the existing studies related to presale cancellation (order cancellation) are mainly focused on the service industry and often link consumers’ withdrawal behavior to the presale length and inventory cost [

40,

41], which are determined by the characteristics of their products. First, most consumers who have preordered a product are highly uncertain about their future consumption status, such as health status and other unexpected conflicts before consumption. Second, most service-based products can only be consumed when they are produced, which indicates that the value of unsold or mid-order backorders will be completely lost after a certain period. Thus, ignoring this phenomenon may result in amiss inventory and pricing decisions. In the service industry, the main links between presales and consumer cancellation behavior are You [

42] and Dye and Hsieh [

43]. They assumed that the probability of consumers’ order cancellation during the presale phase decreases as the presale period draws to a close, and they studied the optimal pricing and ordering strategies of retailers under this assumption. However, the expressions for the change in the probability of consumers’ order cancellation over the presale period in both assumptions were slightly different. According to Mo et al. [

44], as the likelihood of withdrawal increases, the retailers’ optimum selling price and the market penalty for canceling a reservation decreases. You [

45] assumed that the proportion of consumers canceling orders during the presale period is constant, and when the retailers provide partial refunds for this part of customers, the demand function for consumers is linear and exponential. The optimal spot price, the optimal presale price, and the optimal order frequency were solved. Xie and Gerstner [

46] conducted a comparative analysis on whether consumers who canceled the presales offer refunds. The results showed that providing a partial refund strategy can obtain more profit than not providing a refund strategy; that is, to reduce consumer refunds—the cost of ordering rather than increasing the consumers’ cost of unsubscribing. Some scholars, based on providing refunds, have focused on the problem of the optimal refund ratio when consumers cancel [

47,

48].

In presale research in the retail industry, consumers’ cancellation behavior is often linked to inventory costs. Chen [

49] used a two-level supply chain composed of a monopolistic manufacturer and a retailer as the background. The author also analyzed the maximum and partial presales when the manufacturer allows cancellation. In view of an optimal price strategy and ordering strategy, the results showed that compared with not allowing cancellation, allowing cancellation can make manufacturers more profitable. The work is consistent with that of Xu et al. [

50] Zhang [

51] studied the optimal presale strategy for deteriorating goods that allows consumers to cancel and assumed that the probability of consumers’ cancellation in the presale stage and the deteriorating rate of spot goods are constant. However, the study did not conduct a detailed analysis of how consumers’ cancellation behavior affects retailers’ presale strategies.

Given that promotional presales are often conducted in the form of deposit + final payment, how the deposit size affects the retailers’ promotional presale decision and the consumers’ purchase decision when the consumer cancels in the presale stage is also an important issue. At present, the research on presale deposit and consumer cancellation behavior is mainly concentrated in China. One of the main studies is that of Tang and Ang [

52], who took new products as the research object, with consumers who did not participate in the presale, and deposit presale and full-price presale for retailers. A comparative analysis of the optimal pricing, optimal sales, and optimal profit under this strategy showed that the optimal price for full-price presale is the lowest; the optimal sales volume under the deposit presale mode is higher than that of a full-price presale; and the deposit presale can obtain more profits than the other two sales strategies. Yin and Wang [

53] used promotions, such as Tmall’s Double 11, as a background and investigated the influence of the value-added deposit model, which is widely used in presale practices, on retailers’ optimal presale strategies. Their study showed that retailers’ adoption of presale deposit value-added strategies can effectively alleviate consumers’ waiting behavior and can increase sales profits. Chu and Zhang [

54] studied the issue of deposit appreciation in presale but came up with different results. They argued that deposit appreciation is not suitable for goods with lower prices and less profitability in the product. The reason for this is because deposit appreciation is a form of retailer concession, and room is available only for giving price concessions when the selling price is higher, and the retailer is more profitable. Sun et al. [

55] concluded that when uncertainty exists in the supply of a new product, an increase in the presale deposit will lead to a decrease in the optimal retail price. This finding is consistent with the results of the present study. J. Chen and H. Chen [

56] transformed the size of the deposit into the acceptance of the presale model of the deposit, which is reflected in the influence on the expected residual utility. At present, only Xu and Ma [

50] linked the presale deposit ratio with consumers’ cancellation behavior. They assumed that the probability of consumers paying the final payment is a linear function of the presale deposit ratio. The results showed that the retailer can perform refunds and that order presale strategy is better than nonrefundable presale strategy. A full refund is better than a partial refund strategy. However, this study does not consider the influence of consumers’ return behavior on retailers’ inventory and pricing.

2.3. Presale and Return

Research on the combination of presale and return is also abundant. The focus, under the conditions of allowing returns, is similar to the field of presale cancellation, mainly focusing on solving the problems of whether retailers allow returns, the optimal price, and the optimal refund ratio.

Although the focus of the scholars’ studies is slightly different, a common conclusion can be observed regardless of the retailers’ optimal pricing decision. Reducing the probability of consumer returns, which is also consistent with the reality that returns always cause different levels of losses for consumers and retailers, is always beneficial for the retailers. Zhou et al. [

57] focused on whether retailers allow returns. Wang et al. [

58] assumed that the return behavior is only for consumers who purchase in the presale stage and analyzed the retailers’ nonparticipation and participation in presale. The optimal pricing strategy under the condition indicated that the sale is allowed to be returned. Wang et al. [

59] studied the two scenarios of allowing and disallowing returns when retailers participate in presales based on the background of strategic consumers and short-sighted consumers in the market. Li and Choi [

60] focused on the optimal refund ratio and examined retailers’ optimal pricing and refund strategies under three presale strategies of not offering presale, offering a partial refund return service, and offering a full refund return service, assuming that retailers allow consumers to preorder fashion products before the start of the actual sales season. Li et al. [

61] also investigated the changes in consumers’ purchasing behavior and retailers’ profits under these presale strategies and obtained the same results as Li and Choi. That is, the optimal strategy is accepting partial refund returns in presale, which can attract consumers to reserve products and reduce retailers’ risks. Shan et al. [

62] constructed a return mix model based on refund and return cost-sharing in an integrated model of presale and average sales. They concluded that retailers should adopt different return refund strategies for low-, high-, and intermediate-priced goods.

In addition, Mao et al. [

63] believed that the reasons for consumer returns in the presales of conventional and new products are not the same, and different repurchase strategies should be developed to increase the profits of the retailers. The uncertainty of consumer valuation caused the psychological changes of consumers. At present, only Sun et al. [

64] considered the presale deposit ratio and the influence of consumers’ return behavior on the retailers’ optimal presale strategy. In the present study, we assume that consumer acceptance of the deposit presale model is negatively related to the deposit ratio. We translate it into an effect on expected utility, which shows that a higher presale deposit ratio results in a lower presale price for the retailer and reduces its optimal profit. The similarity with the aforementioned article is that consumers are assumed to obtain a full refund when they return the goods. Consumers and businesses need to bear the corresponding losses for the return behavior.

Overall, this study aims to contribute to the presale literature by studying a new presale–deposit design and business pricing decisions. However, given that the complexity of consumers behavior in the real business environment, to avoid the interference caused by other potential factors which is irrelevant to the question we are concerned with, the decision tree model is employed in this study due primarily to its ability in simplifying the consumers’ decision, and can facilitate in abstracting the research question from the complicated real environment. Meanwhile, considering consumers’ behavior of cancellation and return influence on the sellers’ strategies, three situations of consumer decision-making model and retailers’ profit optimization model are established: retailers do not participate in presales, participate in presales (loss on return orders is less than the loss on returns), and join in presales (loss on return orders is greater than the loss on returns). We focus on how the probability of consumer returns and deposit ratio affect the retailers’ presale strategies.

3. Basic Model

This study analyzes the effect of consumer returns on retailer pricing decisions when retailers do not participate in presale activities; that is, during in-stock sales. Retail price is an essential tool in demand management and marketing. Thus, we consider retail price to be an important decision variable [

65]. We assume that the number of consumers in the entire market is 1, the commodity price is

, and that the unit cost is

. The consumer’s valuation of the commodity is

, and each consumer’s psychological valuation of the product is different, and is a random variable that follows a uniform distribution in the interval [0,1]. Its cumulative distribution function is

,

the critical psychological valuation of consumers does not exceed the highest valuation of the distribution interval. Assuming that the returned goods do not affect the retailer’s secondary sales, the retailer will give a full refund, and the consumer will bear the return shipping fee and time cost. The retailer’s loss caused by the consumer’s return is

greater than the loss of the consumer,

.

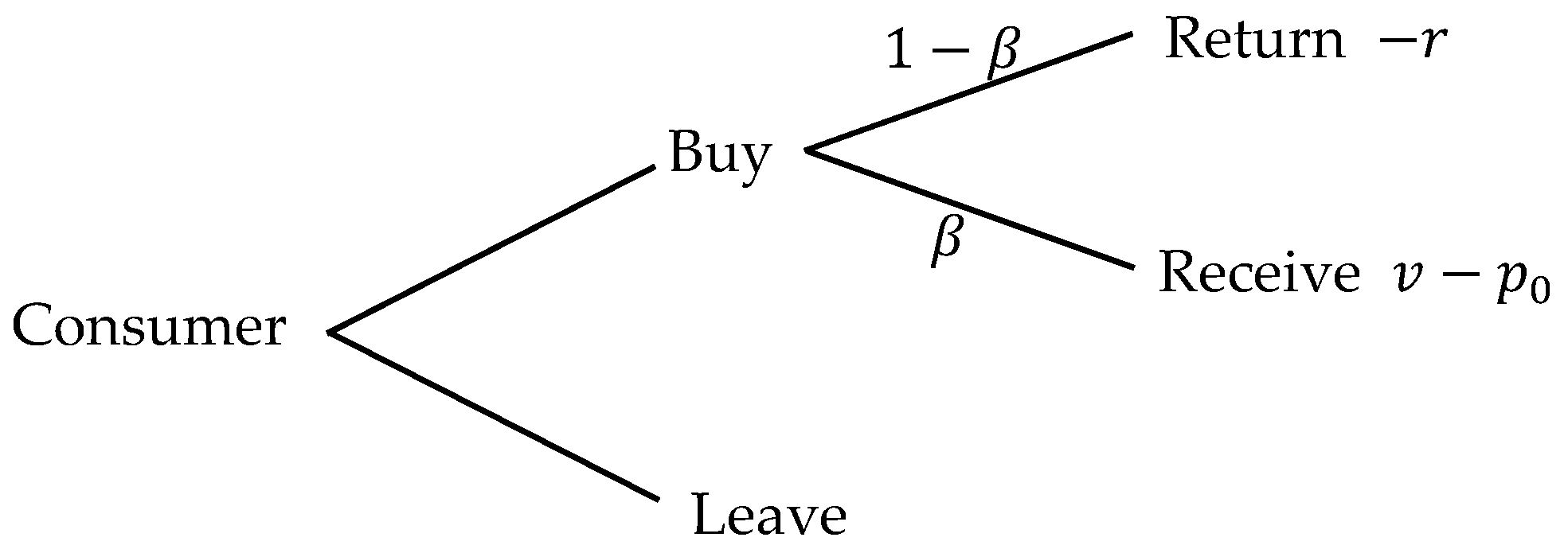

When retailers do not participate in presales, consumers face two choices: buy or leave, as shown in

Figure 1. The probability of not returning the product after purchase is

, and the utility obtained by the consumer is

. The probability of returning the product after purchase is

, and the consumer shall bear the loss

caused by the return, including their time cost, energy, and freight.

Therefore, the expected utility that consumers can obtain when buying a product in a spot sales period can be expressed as follows:

Only when (i.e., ) will the consumer choose to buy the product, and the probability is ; otherwise, the consumer will leave the market. The consumer demand for goods is and . We obtain . Therefore, when , consumers will leave the market and give up buying; when , consumers will buy the goods.

The profit function of the retailer can be expressed as

When the retailer does not participate in the presale and meets the condition , the best price of the product is , the optimal sales volume is , and the optimal retailer’s profit is .

4. Presale Decision Model

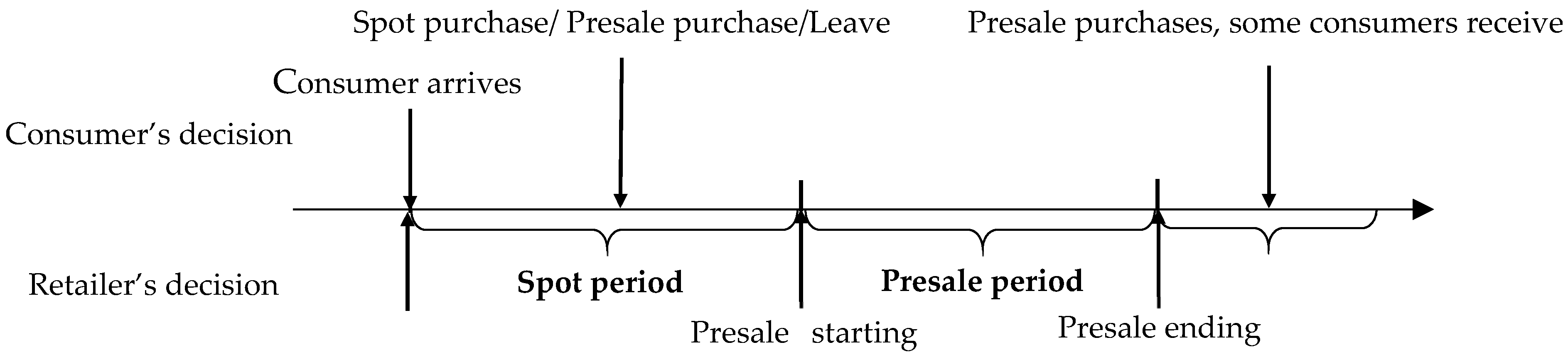

Presale refers to a marketing activity in which the retailer attracts consumers to pay a deposit utilizing deposit + final payment. No shortage of stock exists during the entire sales period, and the inventory cost of the product is ignored. The period is divided into two stages, the spot and presale periods, as shown in

Figure 2.

The consumers’ decision-making process includes whether to buy, cancel the subscription, and return the product. Particularly, whether to buy includes three choices: spot purchase, presale period purchase, and abandon purchase. Therefore, the key to consumers’ decision making is the cancellation loss ratio to the return loss. For the convenience of description, when the cancellation loss is less than or equal to the return loss, it is briefly described as “low deposit strategy;” when the cancellation loss is greater than the return loss, it is briefly described as “high deposit strategy.”

At the beginning of the spot period, the retailer publishes the price of at spot period as ; the price of in presale period is , the presale deposit ratio is and in order to attract consumers to place orders in presale activities, the retailer will give consumers a certain discount; that is to say, the merchant not only sells the products at the normal price, but also gives discounted prices for the products in the presale stage by way of a deposit, and so the spot selling price is higher than the presale selling price, namely , , , means a low deposit strategy and a high deposit strategy, respectively.

The unit cost of the product is at the spot period and at the presale period. During the presale period, that mass production can obtain scale advantages (i.e., ). Consumers can buy in the spot or presale period, and no difference exists in the valuation of the goods. If the consumer cancels, then the deposit he paid is not refunded; that is, the cancellation loss is . If the consumer returns after paying the balance, then the return loss is . As for the retailer, if the deposit is extremely low, it will not be able to make up for the loss caused by the consumer’s cancellation. Otherwise, if the deposit is extremely high, then the consumer will pay the balance and return the goods after recieving the receipt, such that the retailer will lose more in return. Therefore, retailers should decide on the presale deposit ratio reasonably.

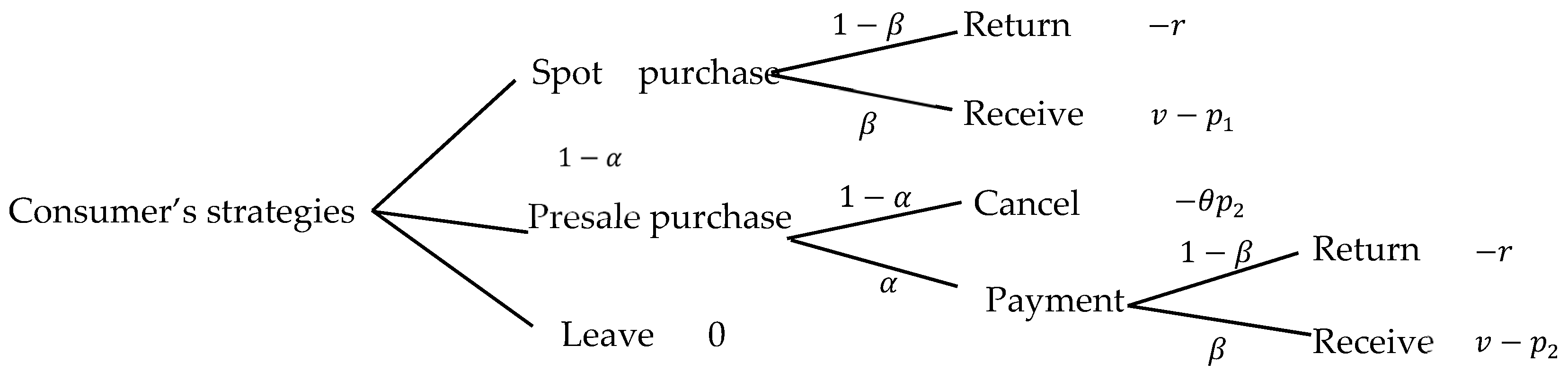

4.1. Low Deposit Strategy

When consumers are dissatisfied with the product and when the cancellation loss is less than the return loss, they will cancel the order and lose the deposit. During the presale period, the probability of consumers paying the final payment is

; that is, the probability of cancellation is

. At the same time, set

, where

,

.

represents the probability that the consumer will not unsubscribe when the presale does not pay the deposit, and the consumer’s order is reserved for the sensitivity coefficient of probability to the presale deposit ratio, the consumer’s decision-making process can be see in

Figure 3.

The utility of consumers buying goods in the spot period can be defined as

The utility of consumers buying goods during the presale period can be expressed as

Take

and

. The following conditions must be met:

,, . Then, let

When

,

. Consumers will buy in the presale period, and the purchase probability is

When

,

. Consumers will buy in the spot period, and the purchase probability is

In other cases, consumers will leave the market.

The retailer’s net profit over the whole sales cycle at this time is the amount of the profit in the spot, and the profit in the presale era is as follows:

When the following conditions are met:

,

,

, the optimal of product price in the two stages is:

Then, the optimal sales volume is

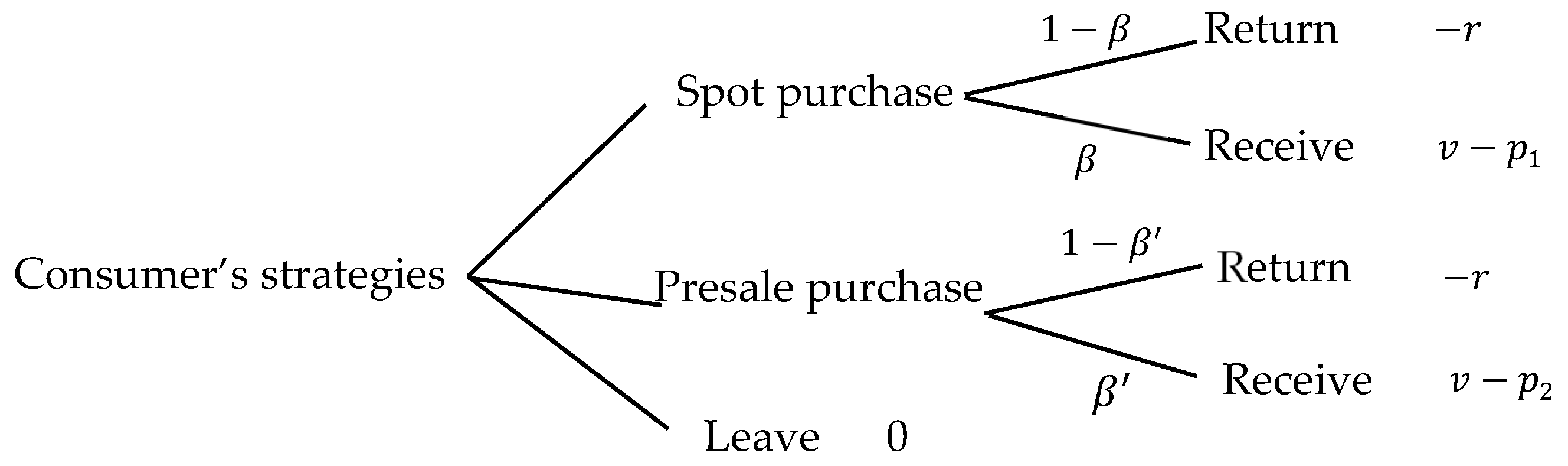

4.2. High Deposit Strategy

When the cancellation loss is greater than the return loss, consumers will return the goods to avoid cancellation loss. The probability of a consumer’s return is set to

. The return includes the return of the consumer due to the consumer’s own reasons and the return converted from the cancellation activity, which should satisfy

, that is,

(see in

Figure 4).

The utility of consumers buying in the spot period can be expressed as

The utility of consumers buying goods during the presale period can be defined as

Take

and

. The following conditions must be met:

,

,

. Then, let

Consumers whose valuation of the product is within the range of

will choose to purchase during the presale period. The purchase probability is

When

,

. Consumers will buy in the spot period, and the purchase probability is

The total retailer profit is

When

,

,

. The optimal product price is

Then, the optimal sales volume is

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Effect of Return Rates (Retailer Nonparticipation in Presales)

Hypothesis 1 (H1). When the retailer does not participate in the presale, the consumer’s willingness to return () and the optimal selling price () decrease.

When the retailer does not participate in the presale, the best-selling price is . At this time,. That is, holding other parameters constant, decreases with increasing . As increases, the probability of consumer return decreases. The expression shows that the smaller the return loss consumers may face at this time, the greater the willingness to buy. In contrast, the retailer may face a reduction in the return loss. When the retailer’s optimal sales and profits remain unchanged, the retailer can reduce the loss to consumers in the form of lower prices.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). When the retailer does not participate in the presale, the retailer’s optimal sales volume () and optimal profit () increase as the consumer’s willingness to return () decreases.

When the retailer does not participate in the presale, the optimal sales volume and the optimal profit are ,0,,.

Each factorization of is greater than zero, which yields ; that is, and increase with . From another perspective, the profit per unit product when the retailer obtains the maximum profit can be expressed as . The profit per unit product will also increase. When the unit product’s expected profit and sales volume increase, the total profit must be increased. Whether for consumers or businesses, the influence of the return behavior is always negative and will face corresponding losses, which is why retailers in real life often take many measures to reduce the probability of consumers returning goods. Reducing the likelihood of consumers returning goods can improve consumer satisfaction and increase the sales volume and sales profits of the retailers, which can achieve a win–win effect.

5.2. Effect of Return Rates (Retailer Participation in Presales)

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The retailer’s optimal spot price is not affected by the presale deposit and decreases asincreases.

, and . The optimal spot price decreases as increases. When increases, that is, when the consumer’s return probability decreases, the return loss faced by the retailers who sell the same number of goods will be reduced. This part of the loss is reduced while keeping the total sales profit unchanged, and the retailers can reduce the product’s price, thereby giving profits to consumers.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). When the retailer adopts the low presale deposit strategy,decreases with the increase of. When the retailer adopts the high presale deposit strategy,decreases with the increase of.

, and .

Then, , and , thereby proving Hypothesis 4.

Combining the results of Hypothesis 3 and 4, for consumers, the smaller the probability of return is, the more advantageous it will be. The optimal spot and presale prices are proportional to the likelihood of return.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). When the retailer adopts the low presale deposit strategy,increases with. When the retailer adopts the high deposit strategy,increases with. When the retailer adopts the low presale deposit ratio, the optimal total sales amount.

During the entire sales period, , and . In the same manner, when the retailer adopts the strategy of high presale deposit ratio, the optimal total sales of the entire sales period is , and . Thus, Proposition 5 is proved.

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Regardless of whether the deposit is high or low,andincrease with β.

Then, . Similarly, we can obtain , ; that is, and increase with . The effect of return behavior is negative for consumers and retailers. Thus, when increases, the probability of return of consumers decreases. At this time, not only will the sales volume increase, but the retailer will also sell unit products. The available profits will also increase, and the total profit will inevitably increase.

In summary, regardless of whether the retailer adopts a high or a low deposit strategy, the lower the probability of consumers returning the goods is, the lower the retailer’s two-phase selling price, the greater the optimal sales volume, and the greater the total profit will be.

6. Numerical Analysis

The returns rate () and deposit ratio () are key factors influencing the decision of consumers and retailers, combined with the previous model and results analysis, this section will use numerical analysis to verify the results of the above model, so as to more intuitively understand the impact of and changes on consumer purchasing decisions and retailer optimal prices, optimal sales, and optimal profits. Scenario 1 analyzes the situation when the deposit rate remains unchanged, and the retailer sales strategy is mainly affected by the return rate; that is, the influence of on the optimal prices, optimal sales volume and optimal profits. Similarly, in Scenario 2, the impact of the deposit rate on these three is considered in turn, under the condition that the return rate remains constant. The first two scenarios are analyzed in consideration of the retailers participation in the presale, but do they have to participate in the presale? Scenario 3 compares and analyzes the optimal sales volume and profit when the retailers participates in the presale or does not participate in the presale.

6.1. Effect of Return Rate

6.1.1. Effect on Optimal Price

Let

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

. When the retailer adopts a low presale deposit strategy,

. When the retailer adopts a high presale deposit strategy,

.

and

vary with

, and

and

vary with

, as shown in

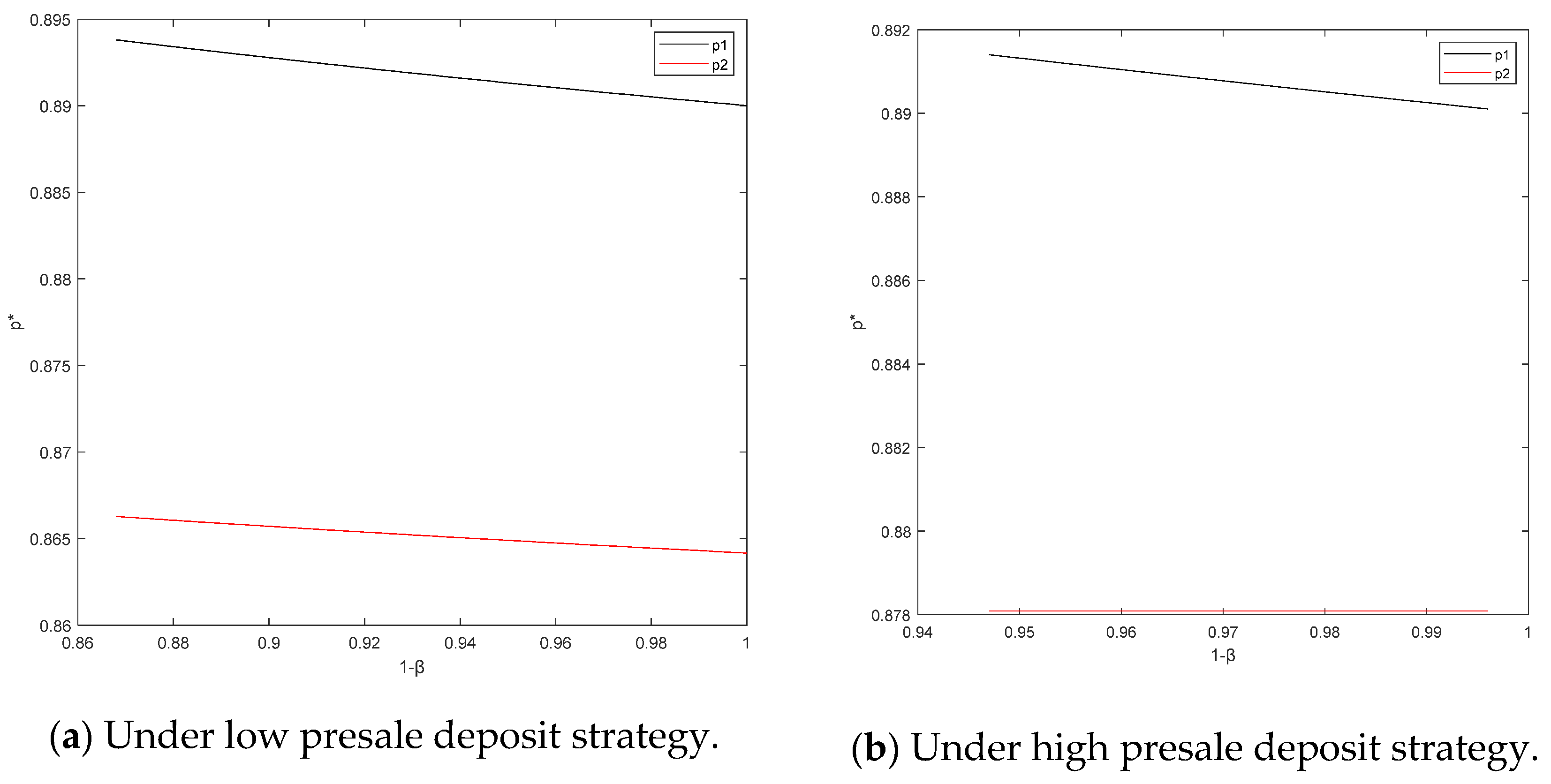

Figure 5.

and

vary with

; and

and

vary with

, as shown in

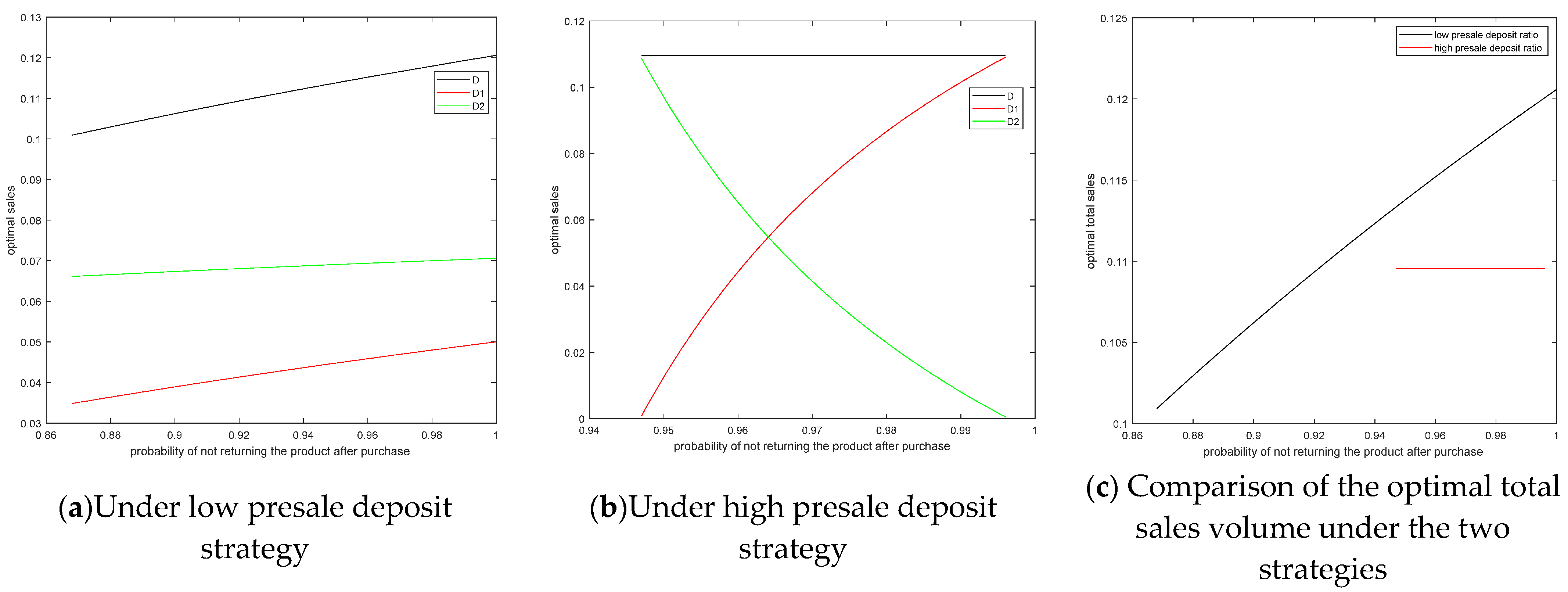

Figure 6. The effect of

changes on

and

, as shown in

Figure 7.

When the retailer adopts a low presale deposit strategy, the optimal spot price takes the values . The optimal presale price takes the values . When the retailer adopts a high presale deposit strategy, takes the values . is a constant, and its size is independent of . When , . When is equal, the optimal spot prices under the two strategies are the same. Given that the range of variation of under the two strategies is different, the corresponding optimal spot price value ranges are slightly different. When , ; thus, the a constant holds.

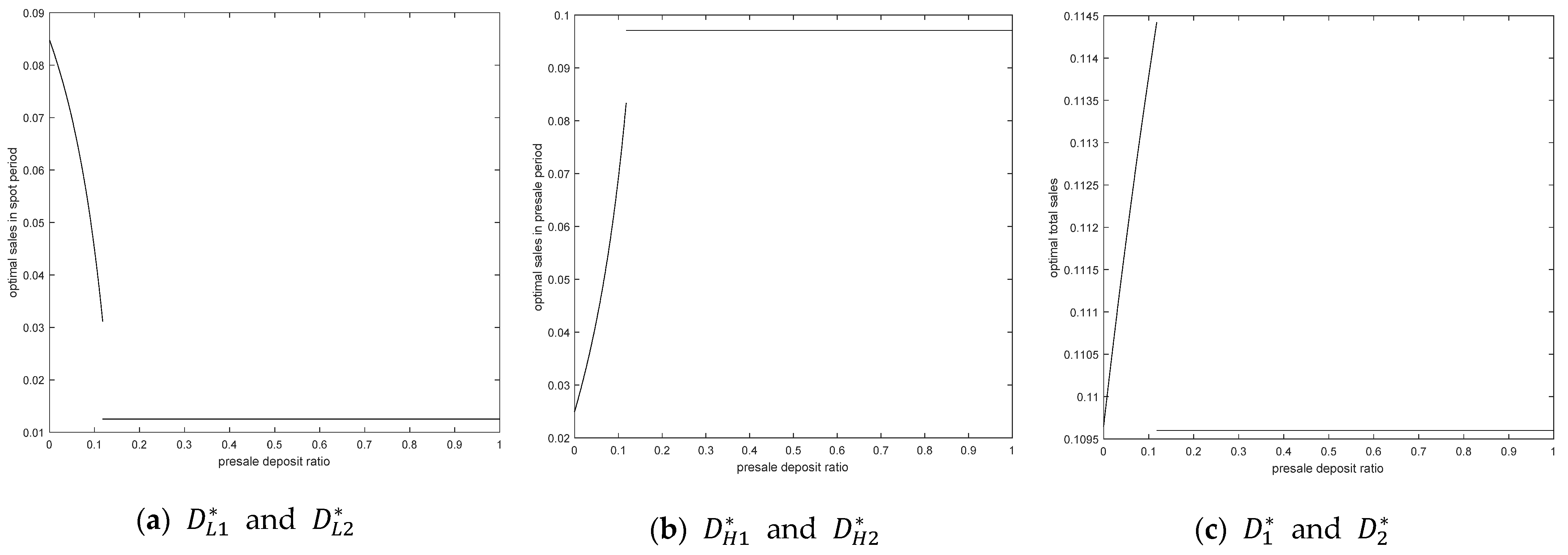

6.1.2. Effect on Optimal Sales Volume

When the retailer adopts the low presale deposit strategy within the constraint range, and all increase with . That is, when the probability of a consumer backorder decreases, the optimal sales volume of consumers can increase on the spot and presale periods simultaneously, and the total sales volume also increases. By comparing the optimal sales volume of the two phases, we can find that the optimal sales volume of the presale period is always more prominent than the spot period when varies within the constraint. Similarly, when the retailer adopts a high presale deposit strategy, increases with . The change of is precisely the opposite; decreases with the increase of when and only when , . Given that the changes in have the same and opposite effect on and , is constant at 0.1096 within the constraint range regardless of . When is within the range of , the total sales volume of the retailer using a low presale deposit strategy remains the same, even though the total sales volume increases. That is, when the return probability of consumers is low, the retailer taking a low presale deposit ratio strategy is better than a high presale deposit ratio.

6.1.3. Effect on Optimal Profit

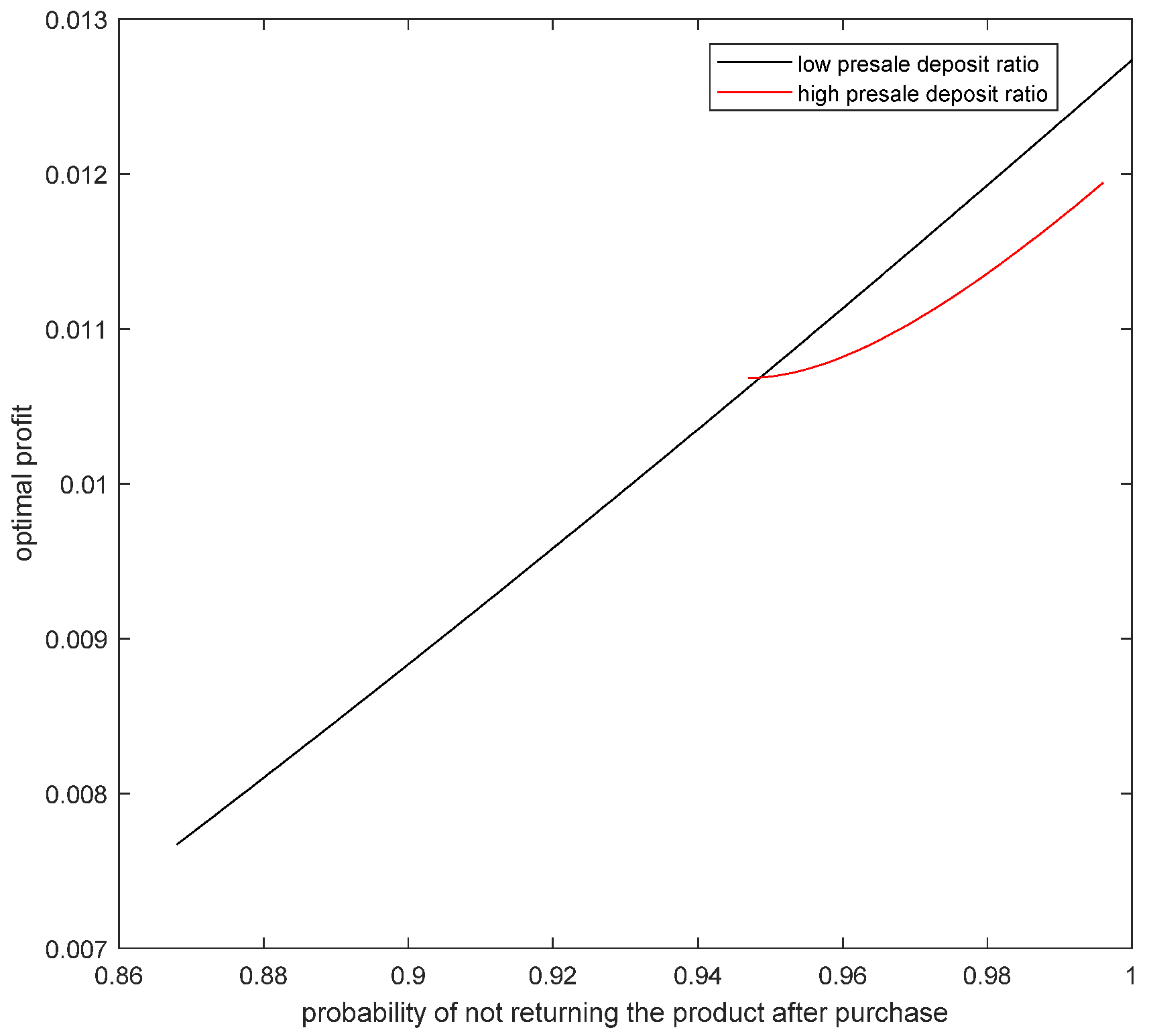

When the retailer participates in presales, taking

,

, the optimal profit obtained by retailer adopting a high presales deposit strategy is smaller than that of adopting a low presales deposit strategy. That is, the larger it is, the more profit the retailer can obtain by adopting a low presales deposit strategy, as shown in

Figure 7.

6.2. Analysis of the Effect of Deposit Ratio

6.2.1. Influence on Optimal Price

When the retailer adopts a low presale deposit strategy,

, making

and

vary with

, as shown in

Figure 8. Let

and

, making

,

,

,

, and

vary with

, as shown in

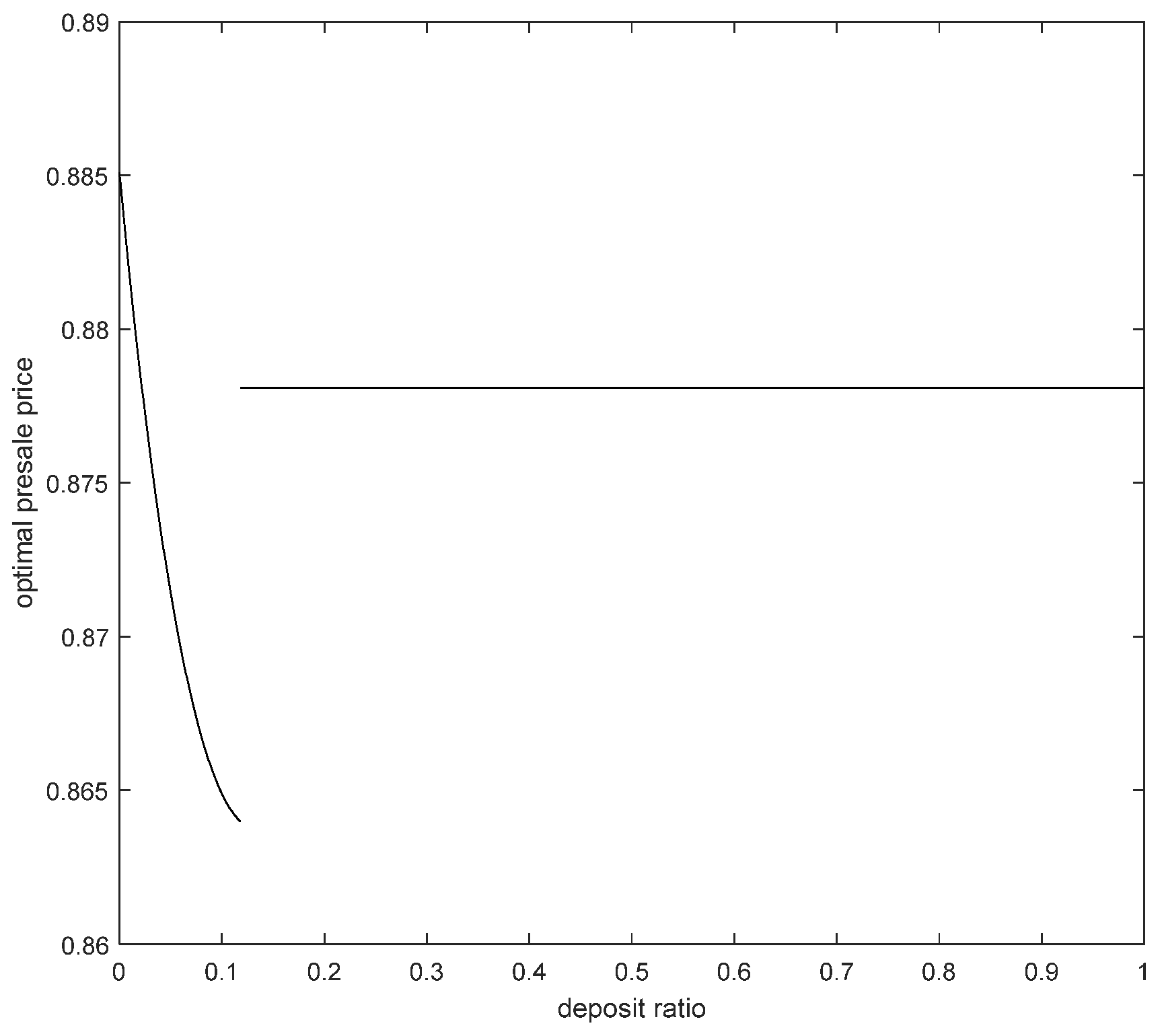

Figure 9.

Given that

is independent of

, when

, the presale price is constant at 0.8781. When

, the optimal presale price

decreases with the increase of

, as shown in

Figure 9. When

, the minimum value of the presale price is 0.864, and when

, the maximum value of the presale price is 0.8851. When

, the optimal presale price is equal in both cases, and it is 0.8781.

6.2.2. Effect on Optimal Sales Volume

decreases with the increase of when the retailer adopts a low presale deposit strategy. obtains the minimum value of 0.0311 when , . The trend of with is opposite to . When the retailer adopts a high presale deposit strategy, increases with , and the maximum value of is 0.08332. However, regardless of whether changes, . The results show that when is small, increasing the sales in the spot period is favorable, and when is large, increasing the sales in the presale period is favorable. For the total sales volume , which increases with , the optimal total sales volume takes the value . When the retailer adopts a high presale deposit strategy, is independent of the size of . When other parameters are constant, is constant at 0.1096; that is, it satisfies . When , the total retailer sales volume is the maximum.

6.2.3. Effect on Optimal Profit

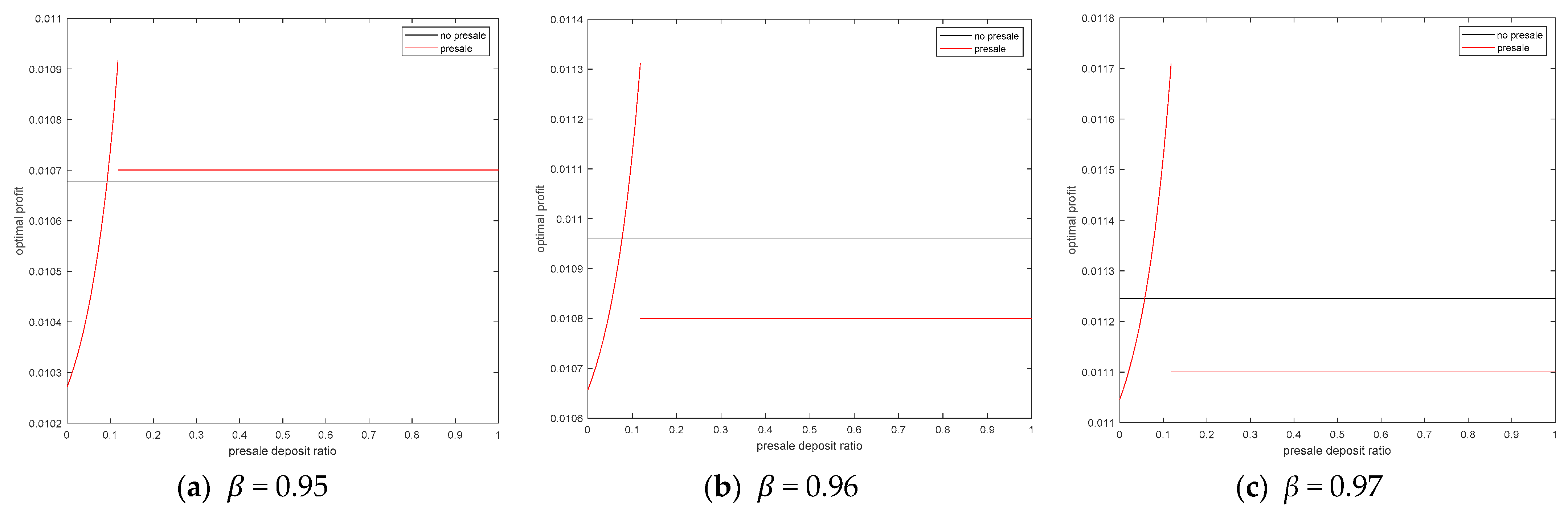

Keeping other parameters constant, let

,

, and

. The retailer’s total profit varies with the change of

, as shown in

Figure 10.

(1) Under the low presale deposit strategy, there exists Under the high presale deposit strategy, there exists a constant , indicating that the retailer’s optimal profit increases with . Therefore, reducing the consumer’s return rate to enhance profits is always beneficial.

(2) When and , neither an extremely high nor an extremely low deposit is optimal. When and only when is limited within a certain feasible domain will the optimal profit obtained by the retailer with a low deposit strategy be greater than that with a high deposit strategy.

(3) When , the optimal profit under the low presale deposit strategy is greater than that under the high presale deposit strategy. Thus, the lower the probability of consumer return is, the more advantageous it will be for the retailer to adopt the low presale deposit strategy.

(4) When the retailer adopts the low presale deposit ratio strategy, the optimal profit of the retailer always increases with in the three cases of , , and .

When keeping constant, reducing the probability of consumer returns is always advantageous for the retailer. Moreover, the lower the probability of a consumer returns is, the more beneficial it will be for the retailer to adopt the low presale deposit strategy. Reducing the likelihood of customers’ returns is beneficial to increase revenue and benefit during the whole sales process. The lower the possibility of buyer returns during the presale phase is, the more favorable the policy of a low presale payment ratio will be.

6.3. Comparative Analysis

6.3.1. Effect of Returns Rate

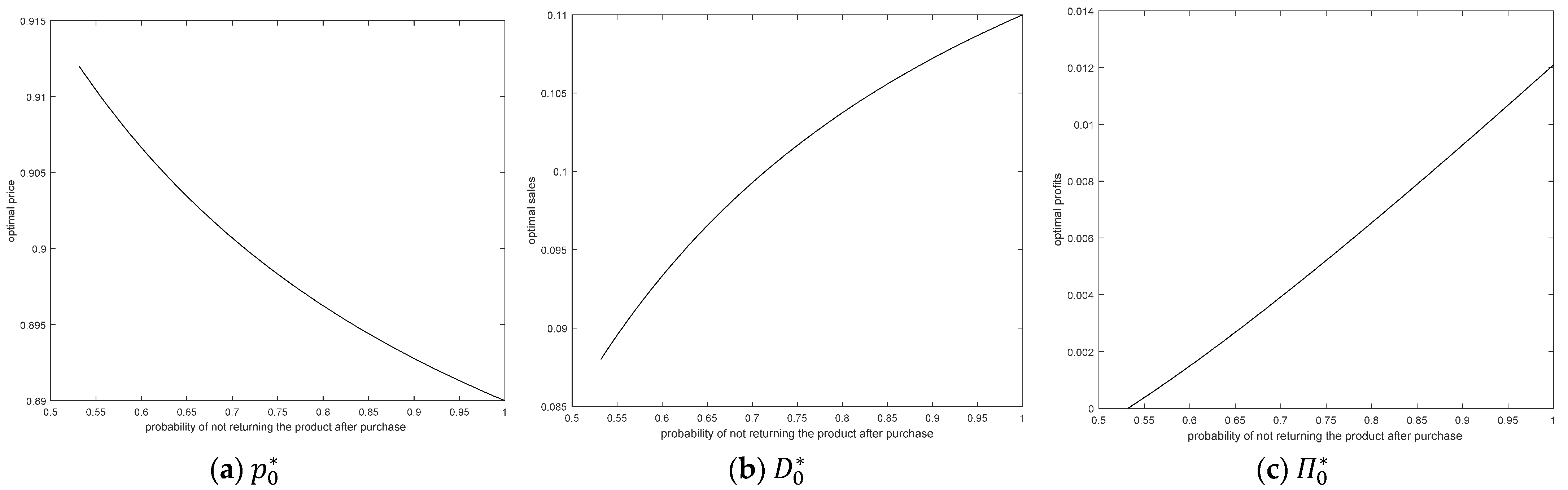

To observe the effect of the changes of on , , and under the scenario of a retailer not participating in presale more intuitively, let , , and . We can obtain and make the graphs of , , and as changes.

As shown in

Figure 11,

decreases monotonically as

increases, and

and

increase monotonically as

increases. When

, the retailer′s optimal price is maximum

. When the consumer’s return rate is high and keeping the optimal sales volume constant, the retailer needs to compensate for the increased return loss by increasing the price. When

,

, and the retailer’s optimal sales price is the lowest. The results show that reducing the probability of consumer returns can increase sales and boost profits. Consumer returns are more pronounced during promotional activities, and retailers should conduct a statistical analyses of the reasons for store returns to target the reduction of return probability.

6.3.2. Effect of Deposit Ratio

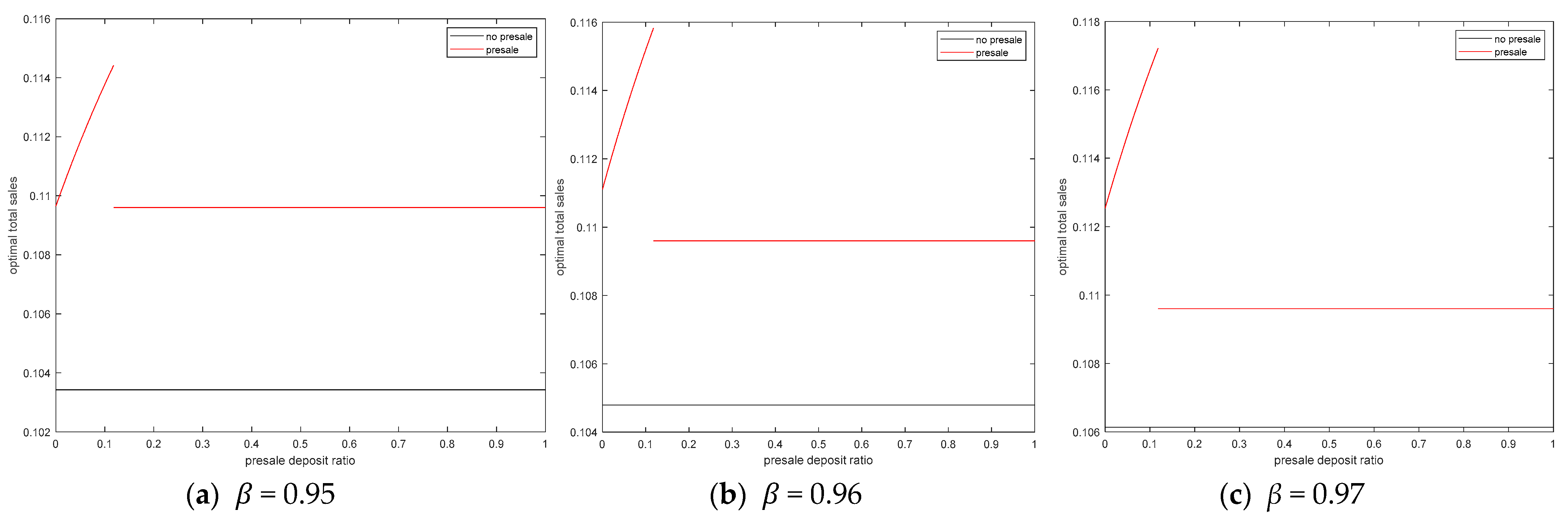

In view of many parameters, assessing the results of direct comparison of optimal sales and optimal profit is difficult if the retailers participate in the presale, as shown in

Figure 12.

Although the maximum profit that a retailer can earn when not participating in presales increases with , the total amount of sales when a retailer participates in presales is greater than not participating. Therefore, from the perspective of promoting sales, promoting sales when the promotional presale model is selected for conventional products that have already appeared is always practical.

Figure 13 shows that

when

,

when

,

when

, and the profit obtained by the retailer by participating in the presale is greater than the profit obtained by not participating in the presale when

.

when

,

when

,

when

, and the profit obtained by the retailer by participating in the presale is greater than the profit obtained by not participating in the presale when

.

when

,

when

,

when

, and the profit obtained by the retailer by participating in the presale is greater than the profit obtained by not participating when

.

In summary, from the perspective of profit maximization, whether a retailer participates in presales should be measured based on the combination of the presales deposit ratio and the probability of nonreturn of goods by consumers. If the probability of consumer return is the same, then retailer participating in presales will not affect the optimal price at the spot stage. Although retailers can obtain more sales by participating in presales, participating in presales is not optimal for retailers from the perspective of profit maximization. If and only if they adopt a low deposit presales strategy and and are limited to a certain range will the profit gained from participating in presales be better than the profit gained from not participating.

6.4. Discussion

Presale has been commonly used in the service industry, such as in air ticket reservations, hotel reservations and promotion activities launched by shopping platforms. However, the high cancellation rate and return rate of consumers are extremely prominent problems in various presale activities. Existing studies have proved that retailers’ pricing strategies (premium, discount or equival), the proportion of the deposit (high or low) and the return strategy (whether return is allowed) have a powerful impact on consumers’ cancellation and return behavior. This study investigated the online presale promotion strategies of retailers based on consumers’ strategic behavior, and focused on how consumers’ cancellation probability and deposit ratios affect retailers’ presale strategies.

According to the above data analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn. Firstly, the ideal position prices of retailers in non-presale and presale (loss of orders is less/greater than return loss) are equal. Secondly, regardless of whether the retailer participates in presales, reducing the probability of consumer returns, which increases the total sales volume of the whole sales process and enhances the maximum profit of the entire process, is always beneficial for the retailer. Thirdly, when retailers participate in presales, the low presale deposit ratio strategy is better than the high presale deposit ratio strategy to promote sales. Finally, the profit obtained by a retailer participating in presales is greater than the yield obtained without participating in presales when the retailer engages in presales and adopts a low deposit ratio strategy, and the probability of consumer returns and the presales deposit ratio is limited to a specific range.

7. Conclusions

In recent years, the presale model has been widely used due to its significant advantages and has also become a hot spot for domestic and international scholars. Although presales have been mentioned in related studies, few scholars have distinguished between the two presale models and conducted an in-depth and targeted research on online promotional presales.

Combined with the sustainable operation plan products, this study takes the “deposit + final” payment online promotional presale model as the research goal. It initially compares and analyzes the similarities and differences between online promotional and new product presales in terms of product characteristics and the presale process. Then, we consider the consumers’ unsubscribe behavior in the presale stage and the return behavior in the whole sales stage. Furthermore, the optimal sales decision of the retailer in the three cases of not participating in the presale, participating in the presale (the loss on orders is less than the loss in return), and participating in the presale (the loss on orders is greater than the loss in return) is discussed and compared. Finally, on the basis of the model results, we provide suggestions on whether to participate in presales and how to make the optimal deposit ratio decision when participating in presales.

Through the above analysis, the major findings can be concluded as follows: (1) Whether a retailer participates in presales, reducing consumer return rates is always beneficial to their sales and profits. (2) When the retailer participates in presales, the lowest presale deposit ratio strategy is the best, and the optimal sales volume of which is always more significant than the optimal sales volume under a high presale deposit ratio strategy. (3) When the retailer participate in presales, the lower the return rate of consumers is from the perspective of profit maximization, the lower the deposit rate used by the retailer will be. (4) When retailer adopts a low deposit strategy and the consumer return rate and presale deposit rate are limited to a certain range, the profit gained from participating in presales is greater. For retailers, whether to participate in the presale should be determined based on the actual situation of the company. On the one hand, the presale deposit ratio is not as high as possible. The deposit ratio should be controlled within a specific range to avoid consumers’ speculative cancellation behavior. On the other hand, the presale deposit ratio should improve the quality of goods and enhance order fulfillment accuracy.

As introduced above, although this study concluded some significant findings which provide useful practical implications for both practitioners and managers, there remain several limitations. First, the decision tree model used in this study simplifies consumer’s decisions. Whether the findings concluded in this study are still established in other models and in reality is worth further investigation. Second, the COVID-19 pandemic has sharply affected these aspects of society, including consumers’ consumption customs and behavior. The impact of COVID-19 on retailers’ presale implementation and consumers’ decisions has not yet been discussed in this paper. Thus, investigating the online presale promotion model based on consumer strategic behavior under the COVID-19 circumstance is a promising future research direction.