Abstract

Over-reliance on hired jobs in the public and private sectors of the Nigerian economy has discouraged most graduates from becoming entrepreneurs. This leads to unemployment, poverty and low economic growth that breed insecurity. Drawing from the formative perspective, this study analyzed the mediating role of self-efficacy (SELF) and the moderating effect of entrepreneurial support (ENTSP) in relation to individual-level entrepreneurial orientation (ILEO; innovativeness, risk taking and proactiveness) and venture creation (VC) among Nigerian graduates. A reflective/formative type II method was applied to test the model’s relationships using 291 survey responses. The result of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) reveals that the indirect relationship between ILEO and VC through SELF was positive and significant but negatively moderated by ENTSP, implying that not all instances of ILEO will result in VC through SELF because ILEO can directly lead to VC. The finding also indicates ENTSP did not have an impact on strengthening the relationship between SELF and VC. A limitation lies in the chosen method that weakens the generalizability of the result, but future studies considering a longitudinal survey are suggested. This study extends the entrepreneurial orientation model to enhance the venture creation literature theoretically and practically. We recommend intervention agencies to initiate effective ENTSP covering financial, non-financial and incubation services required to boost VC activities.

1. Introduction

In recent times, campaigns by governments, institutions and private walks of life have been directed towards the achievement of sustainable self-reliance [1]. This is in recognition of the fact that governments and other walks of life alone cannot cater and provide means of living to all citizens [2]. As such, it becomes necessary for societies to devise means of living especially through self-employment [3]. Therefore, to be in self-employment, people need to embark on entrepreneurship activities [4]. However, these activities do not just exist on their own but require a medium for carrying them out. Media for undertaking entrepreneurial activities are simply known as ventures, enterprises, companies, entities or even business organizations as the case may be [5]. This means that, in the quest of individuals that are passionate to undertake entrepreneurship activities either as a means of self-reliance or just to pursue a career dream in life, they will be required to create businesses through venture creation that will enable them to actualize their respective business desires in production, manufacturing, wholesaling, retailing or other forms of agency services. In addition, this type of activity largely depends on individuals’ perception of risk, innovation and proactive abilities which are informed by his or her confidence in performing the activity [6,7,8]. As such, Gatewood et al. [9] outlined some cognitive orientations towards the activity that constitute gathering market information, estimating potential profit, finishing the groundwork on products and services, developing the structure of the company and setting up the business operation. However, the extant literature has also demonstrated the importance of supportive mechanisms in helping the process, especially when started by nascent entrepreneurs [1,10,11,12,13].

This scenario can be seen more practically in developing economies such as Nigeria, where there are problems of unemployment, poverty and low economic growth that are considered possible causes of insecurity [14,15,16]. Recent statistics show that youths and graduates constitute 64% of working-age groups in the country, but unfortunately, the rate of unemployment has not been favorable in recent times [17]. For instance, in 2017, the national unemployment rate was 18.8%, which later increased to 23.1% in 2018 to 2019 [18,19] and thereafter rose alarmingly to 33.5% in 2020 [20]. These fluctuations were accompanied by a decreasing level of underemployment from 28.6% to 22.8% that brought the combined rate of unemployment and underemployment to 56.1% in the first quarter of 2021 [21]. As a result, no fewer than 25 million graduates are currently unemployed [2].

One of the reasons for this widespread unemployment among school graduates is that the majority of them are in the quest of gaining hired jobs from white collar offers [2,22,23]. This trend can be traced back to the pre-colonial era under the liberal education policy designed to teach Nigerians how to read and write as criteria for hiring the positions of clerks, inspectors and interpreters [23,24]. Therefore, this motive influenced the people to move from their initial artistic way of life and rather pursue education in anticipation of being hired by white collar opportunities [24,25,26,27]. Unfortunately, this mindset still exists where graduates assume acquiring educational certificates is like a passport of employment [28]. To some extent, some graduates even consider self-employment as an odd activity for persons that are unable to find any job [3,29,30]. A picture of the scenario can be seen more practically from the last federal recruitment by the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) in 2019 that advertised only 1000 vacancies but received 25.60 million applications from graduates vying for this white collar opportunity [18]. By implication, not even 1% of the applicants could be considered for appointment into the corporation. As such, the large proportion of unsuccessful applicants returned back to the labor market. Meanwhile, this represents the imbalance between education and job mismatch among school graduates that has been causing incessant unemployment problems [31,32].

Presently, there is reliable information on the existence of some 37.07 million small and medium-scale enterprises (SMEs) which are expected to provide approximately 84% of jobs to teeming Nigerians [33]. However, there is a shortage of evidence to demonstrate graduates’ venture activities from the census conducted on these emerging businesses in Nigeria. This is the case even though the government, in an attempt to address some of the economic mishaps, has established policies and programs that will extend support to enterprising Nigerians willing to be self-reliant, including graduates. Some agencies responsible for this mandate include the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), the Small and Medium Scale Enterprises Development Agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN), the Bank of Industry (BOI), the Graduate Entrepreneurship Fund (GEF), the National Directorate of Employment (NDE), the Industrial Training Fund (ITF), N-Power and Trader Money Programs, to mention a few [22,29,34,35,36,37,38].

Therefore, from the programs listed above, it can be noticed that the GEF program is very specific and designed for graduates that opt to be self-reliant after graduation. Accordingly, the mandate of the scheme is to provide training and support mechanisms for the purpose of strengthening graduates’ start-up activities [39]. Graduates are mobilized into the program during their one-year mandatory National Youths Service Corps (NYSC) before they can become beneficiaries of the scheme. The GEF program covers two areas [38]: firstly, enrolling graduates for apprenticeship training so as to develop their trade skills and entrepreneurial self-efficacies; secondly, sourcing and mobilizing seed funding for the graduates’ start-ups through the BOI or other sister funding agencies.

This understanding motivated the idea of this study to investigate the entrepreneurial orientation of GEF graduates towards venture creation using their level of efficacy and support programs meant to strengthen their start-up phases. Therefore, the following hypotheses (H) were proposed: H1: the greater the level of self-efficacy held by Nigerian graduates, the more it positively mediates the relationship between individual-level entrepreneurial orientation and venture creation activities; H2: entrepreneurial support moderates the relationship between self-efficacy and venture creation such that high-level entrepreneurial support would strengthen the relationship between the self-efficacy and venture creation activities of Nigerian graduates and vice versa.

Subsequent chapters of this study include the following: Section 2 presents the theoretical background, hypothesis development and research framework. Section 3 presents the methodology, measurement items, data collection, sampling and method of data analysis. Section 4 presents the results of the analysis and findings of the study. Section 5 presents discussions on the findings. Section 6 presents the conclusion of the study, and the last section presents limitations and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature Review

A substantial number of scholars are of the opinion that venture creation (VC) relates to the activities of planning, organizing and establishing new business enterprises [40,41]. Previous knowledge on VC shows that the inception, launch and development of new businesses depend on the interconnection between cognitive skills and behavioral traits [42]. Specifically, cognitive resources are the hallmark of entrepreneurial actions that, in turn, make entrepreneurship indicators good predictors of action [43]. However, the pursuit of VC lies between the identification of opportunities and subsequent actions of individuals in starting the VC process [40]. In contrast, Cardon and Kirk [44] argued that opportunity identification alone does not necessarily translate into entrepreneurial action, noting that VC entails establishing a new company from scratch to the business status level. As such, the enquiry into what entrepreneurs do to start up new ventures suffices, especially from the nascent perspectives [45].

The theoretical framework of this study was built from the literature depicting start-up actions in venture creation as evident in Gatewood et al. [9]; the entrepreneurial orientation (EO) model as evident in Anderson et al. [46], Lumpkin and Dess [7], Cho and Lee [47] and Miller [48]; the mechanism of the effect of self-efficacy as evident in Bandura [8], Lent and Brown [49], Rogers et al. [50], Wendling and Sagas [51] and Marshal et al. [52]; and the contingent role of entrepreneurial support as evident in Fichter and Tiemann [53], Bolton and Lane [6] and Liu and Gu [54].

The bottom line is that the EO concept has been receiving increasing attention in entrepreneurship, which makes it an important construct in the present literature [55]. Miller [48] described the EO concept as a firm’s actions towards risk taking, innovation and proactive abilities. However, the framework of social cognitive carrier theory (SCCT) plays a fundamental role as a determinant of goal choice, satisfaction, performance and educational and occupational interest development [49]. One cognitive factor of SCCT is self-efficacy, which Bandura [8] and Lent and Brown [56] consider as a person’s belief in his or her abilities to perform a specific action or behavior. Consistent with Ladd et al. [57], the EO concept and self-efficacy are both drivers of entrepreneurial intention. The literature finds that intention leads to a specific behavior [58], and this informs the entrepreneurial activity of starting a new venture [59]. For instance, Gorostiaga et al. [60] found that innovativeness, risk taking and proactiveness were among the EO indicators that expressed a simultaneous association with self-efficacy. Khedhaouria et al. [61] and McGee and Peterson [62] both affirmed this in their respective studies that showed self-efficacy is positively related to entrepreneurial orientation. In contrast, Alam et al. [63] found the mediating role of self-efficacy to be related to the personal values and entrepreneurial orientation of some Malay SMEs in Malaysia. Therefore, this indicates that a framework with these antecedents can be used to understand the actions of individuals in relation to their start-up actions.

Accordingly, Gatewood et al. [9] proposed and validated certain cognitive orientations towards entrepreneurship that are responsible for start-up actions. The authors referred to preparations towards VC which include gathering market information (GMI), estimating potential profit (EPP), finishing the groundwork on products and services (FGPS), developing the structure of the company (DSC) and, lastly, setting up business operations (SBO). They highlighted GMI as a dimension that focuses on sourcing information about customers, suppliers and competitors’ offers. EPP is a dimension that focuses on projections regarding sales, revenue, prices and wage administration. FGPS is a dimension that covers technical aspects of product branding. DSC entails activities regarding budgeting, vision and mission statements of the company. Meanwhile, SBO encompasses the business location, customer service, schedule of operation, channels of distribution, marketing of the company’s services, etc. Therefore, this informed the basis upon which the conceptual framework of this study was developed.

2.1. Theoretical Background

The novelty of management science research has brought yet another important dimension of entrepreneurship referred to as entrepreneurial orientation (EO) [6,48,64]. This concept dates back to Miller’s 1983 work on the correlates of entrepreneurship [47,65]. Even though Miller never used the term “EO”, he developed the first framework upon which EO was built [48,66]. At the onset, it was intended to explain the level of innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-bearing attitudes of the Canadian firms Miller studied [67]. However, the intensity of research later gave rise to the present EO that is now used as a model in the field of entrepreneurship [46,48,64,65,66,68]. Risk taking, innovativeness, proactiveness [55,69], competitive aggressiveness and autonomy [6,66] form the EO model.

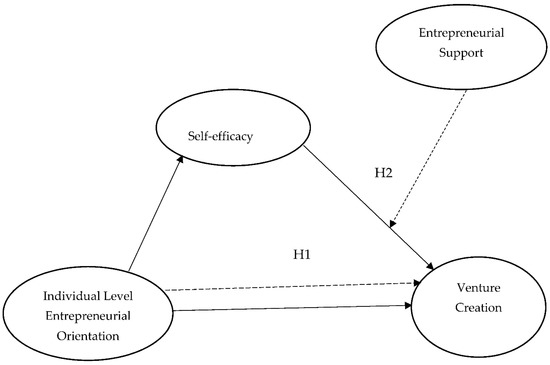

Accordingly, Lumpkin and Dess [7] described the pattern of new entry as the symbol of entrepreneurship, while EO explains the mechanism of how the entry is performed. Therefore, in an attempt to understand the process of new start-ups as in this study, the role of EO cannot be overemphasized. This makes it an important factor at the conceptualization stage, as shown Figure 1. However, it was modeled as a formative measure in line with George [55], using the guidelines of Becker et al. [70], Sarstedt et al. [71] and Ali et al. [72] for a reflective/formative type II second-order construct.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the study.

However, scholarly deliberations depend on whether EO best applies at the organizational level or at the individual level [46]. Some schools of thought argue for the organizational level [68,73,74,75,76,77]; others contemplate the individual level [6,78]. Therefore, Cho and Lee [47], Dai et al. [79] and Fellnhofer [80] mediated with suggestions that the first three dimensions, i.e., innovativeness, risk taking and proactiveness, have been widely applied to explain phenomena under individual-level entrepreneurial orientation (ILEO), in addition to the construct’s unidimensional and multidimensional advantage of interacting with a wide range of variables [7,46,65,66,75,78]. For instance, Caseiro and Coelho [81] attested to its multidimensional role to understand the factor’s impact in relation to other variables. This added to its credence that supported linking it to other predictors as shown in the conceptual framework.

Based on this understanding, Gorostiaga et al. [60] described innovativeness as an aspect of creativity where firms use technological advantages to become a market leader in the introduction of new products and services. Risk taking is the tendency of a firm to commit resources into an investment project that may be unsuccessful, while also assuming the responsibilities of bearing the uncertainties. Meanwhile, proactiveness is considered as forward-looking opportunities concerning how the firm can improvise anticipated market needs in the form of goods or services. For instance, previous studies such as Lurtz and Kreutzer [82] found support for the EO indicators in relation to social venture creation. Similarly, Mamaun and Fazal [83] found that the relationship between proactiveness and entrepreneurial performance is not linear. As such, it was advised for enterprises using this strategy to design and develop timely products and make them available in the market prior to competitors’ knowledge. The testimony of Paradkar et al. [84] is that the majority of new start-ups use an innovation strategy to gain market attention through value-added benefits in customers’ services. In the same vein, Neneh [1] expressed that most nascent start-ups by students used to be innovation-driven. This follows evidence of their high self-efficacies in the intention to start their own venture enterprises. Therefore, Maas et al. [85] and Popov et al. [78] described this approach as a firm’s readiness to experiment with new ideas in an attempt to come up with market solutions through new products and services.

According to some scholars, persistent innovation activities can help businesses to mitigate the expectations of emotions of fear and uncertainty [86,87]. This is because people who anticipate regretting their inactions towards entrepreneurial dreams have chances of starting new ventures in an attempt to address their inaction regret [86]. As such, Maas et al. [85] cautioned that firms not only focus on product enhancement as the most influential aspect of innovation but also take cognizance of process innovation across new markets, new distribution channels and new production systems. Therefore, it becomes imperative for educators to build the efficacies of creativity and risk-bearing culture among their students as this will reduce their low-level innovative abilities [86]. In addition, this will also improve students’ career decision-making self-efficacies during the transition from school to the work environment [88].

2.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy

Previous studies such as Kannadhasan et al. [89] applied a cross-sectional survey to examine the mediating role of self-efficacy in relation to social capital and venture creation among 375 selected Indian entrepreneurs. Their result showed that entrepreneurs’ self-efficacy fully mediates the relationship between social capital and venture creation. Similarly, Puni et al. [90] tested the mediating effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in relation to the entrepreneurship education and intention of some undergraduate students in Ghana. The result of the multiple linear regression revealed that entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the relationship between the entrepreneurship education and intention of Ghanian students towards venture creation. Consistently, Chen and He [91] assessed the impact of strong ties on entrepreneurial intention through the mediating effect of self-efficacy among 327 undergraduate students in China. Their findings from structural equation modeling showed the presence of a positive and significant indirect effect on the relationship between strong ties and the entrepreneurial intention of Chinese students. However, the result indicated only tolerance self-efficacy mediated this relationship, with opportunity identification self-efficacy acquiring the largest mediating role.

Marshall et al. [52] analyzed access to resources and entrepreneurial well-being through the mediating role of self-efficacy among a selection of 258 prospective entrepreneurs drawn from Amazons’ Mechanical Turk Program. The result of serial mediator regression analysis showed that self-efficacy significantly mediated the relationship between the persistence of these prospective entrepreneurs and venture creation activities. In the same vein, Zhao et al. [92] tested the mediating effect of self-efficacy on the entrepreneurial intention of some postgraduate students from five universities using the structural equation modeling technique. Their result showed that self-efficacy significantly mediated the relationship between entrepreneurship learning courses, entrepreneurial experience, risk-taking propensity and the development of the entrepreneurial intention to create new ventures among university students in Chicago.

Conversely, Neneh [1] applied moderated mediation analysis to assess the mediating effect of self-efficacy and the moderating role of social support in the relationship between the entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention of South African university students. The finding showed a positive and significant mediating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between the entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intentions of the students to launch entrepreneurship activities. The result also showed that the indirect relationship between entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention through self-efficacy was positively moderated by social support. In turn, Salami [93] analyzed the mechanism of self-efficacy in the relationship between contextual factors and the entrepreneurial mindset of some selected secondary school students in Nigeria. He found self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between contextual factors and the entrepreneurial intentions of the students surveyed.

Using regulatory focus theory to determine the effect of entrepreneurship courses on British university students, Piperopoulos and Dimov [94] found high-level self-efficacy as the basis of low-level entrepreneurial intention in the theoretical entrepreneurship taught courses, and of high-level entrepreneurial intention in the practical entrepreneurship taught courses, for British university students. Accordingly, evidence from McGee et al. [62] revealed that entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial orientation were positively related to venture performance but in distinctive ways: (1) founders of businesses that are entrepreneurial self-efficacy-oriented tend to show satisfactory performance in new firms, but this fades overtime; (2) entrepreneurial orientation-oriented founders of businesses tend not to have a significant impact on new firms at all.

From this empirical review, it can be deduced that one extant psychological factor with an influencing role in the decision to enter into entrepreneurship is self-efficacy [95]. It is regarded as the mechanism for building interest in entrepreneurship [89,96,97], which is responsible for connecting interpersonal skills and entrepreneurial actions [97]. Xin et al. [88] considered self-efficacy as the magnitude at which people are confident in their abilities to accomplish a given task. Therefore, Bandura [8] expanded it to mean believing in one’s capability to do something that has an impact on one’s life.

It was based on this understanding that the researchers drew premise from social cognitive career theory (SCCT) [49], with emphasis on self-efficacy [8,51]. This was to explore its intermediary role in relation to individual-level entrepreneurial orientation (ILEO) and start-up actions on venture creation (VC) among graduates. Because there is evidence from the review conducted that this area has not received in-depth research attention, especially in the Nigerian context, the researchers proposed H1: the greater the level of self-efficacy held by Nigerian graduates, the more it positively mediates the relationship between individual-level entrepreneurial orientation and venture creation activities.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Support

In the quest of nations to achieve the United Nation’s development agenda through private sector participation [98], the majority of governments around the world have subscribed to the creation of policies and support programs for entrepreneurship development [1]. The literature finds that entrepreneurial support (ENTSP) overlaps in three facets [99]: (i) its inclusion of students in entrepreneurship education (EED) courses [15,31,100,101,102], (ii) government support programs (GSPs), e.g., financial and non-financial [10] and (iii) Entrepreneurship Development Centers (EDC), e.g., incubation centers for skills acquisition [12,29,99]. Accordingly, Li et al. [12] added that incubation facilities not only focus on basic training programs for apprentices but also extend the scope to cover networking services and the provision of capital support for trainees. This helps to coordinate and strengthen the support mechanisms necessary to actualize the venture creation dreams of new starters.

This can be seen more practically through the review of some studies such as Anwar et al. [11] that investigated the moderating effect of government support in relation to entrepreneurial finance and new ventures’ success among 182 newly established ventures in Pakistan. The result of the analysis with the PLS-SEM technique showed that government support moderates and strengthens the association between entrepreneurial finance and new venture creation success in Pakistan. Similarly, Shirokova et al. [103] examined the moderating effect of national culture in relation to university entrepreneurship offerings (curricular and co-curricular programing) and students’ start-up activities at the University of St. Gallen (KMU-HSG), Switzerland. Their result showed that there was a positive and significant moderating effect of specific cultural dimensions in relation to curricular/co-curricular programing and students’ start-up activities at the University of St. Gallen. Conversely, the finding also indicated that university seed funds for students negatively impacted students’ start-up activities.

In a related development, Neneh [1] studied the moderated mediation relationship between the entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention of South African university students through the mediating effect of self-efficacy and the moderating role of social support. The finding showed that the indirect relationship between entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention through self-efficacy was positively moderated by social support. This shows the impact of social support in strengthening the entrepreneurial behaviors of students towards becoming entrepreneurs and, in turn, to create ventures after graduation. Li et al. [12] analyzed the impact of business incubators as an instrument of entrepreneurship development through the mediating role of business start-ups and the moderating effect of government regulations among some Pakistan residents. They found government regulations had a positive moderating effect in the relationship between business start-ups and the entrepreneurship development of these Pakistani residents.

In turn, Guo et al. [104] assessed the moderating role of venture capital investment intensity in relation to e-business model value retention (novelty, efficiency, lock-in and complementarity) and Internet of Things (IoT) mobile value retention for new start-ups in China. Their result indicated that venture capital investment intensity had a moderating effect on the relationship between business model value retention and IoT mobile value retention among new Chinese e-business start-ups. However, the moderation effect was unfavorable to e-business model value retention as it increases efficiency-centered and complementarity-centered e-business models that reduce IoT mobile application value retention.

Shi et al. [105] examined the effect of university support, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and heterogenous entrepreneurial intention on entrepreneurship education through the moderating role of Chinese sense of face among 374 students in Mainland China. They found a positive and significant moderating effect of Chinese sense of face in relation to university support, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, heterogenous entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurship education among the students in Mainland China. In addition, Weiss et al. [106] studied the transition from entrepreneurial intention to start-up behaviors through the moderating effect of regional social capital among some participants of the Swiss Research Institute of Small Business and Entrepreneurship at the University of St. Gallen. Their result showed that cognitive regional social capital weakened the connection between intention and behavior, but the association was strengthened through structural regional social capital that supported new venture creation activities among the participants. As such, they recommended policy makers to enhance regional social capital by decreasing hierarchical social structures to promote new venture emergence within the regions studied. In similar instance, Shu et al. [107] determined EO and strategic renewal influence on government institutional support to enhance business performance in China. Their finding showed government institutional support enhanced EO and strategic renewal but individually. Meanwhile, Veronica et al. [108] studied the role of government support toward facilitating the growth of social SME’s from emerging economy perspective using the predictors of behavioural theory. Their result showed government support plays important role at the launch of the social SME’s but is also limited to the enterprises growth stage.

Other empirical evidence includes that of Hoque [13], which found a significant moderating effect of government support policies (GSPs) on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and SMEs’ performance in Bangladesh. Nakku et al. [10] also found a significant moderating role of government support (financial and non-financial) that was responsible for increasing the association between entrepreneurial orientation and the performance of agricultural-based SMEs in Uganda.

This review sheds more light on the contingent role of entrepreneurial support as a factor of interest towards enhancing the cause of entrepreneurship activities (e.g., Hoque [13], Shu et al. [102] and Veronica et al. [103]). To some extent, Stayton and Mangematin [109] considered it as the mechanism for increasing entrepreneurial orientation and strengthening the process of new start-ups. Therefore, to narrow the scope of this understanding to the Nigerian context, it can be seen that the government has implemented several intervention programs to enhance entrepreneurship activities through agencies such as: the CBN, BOI, GEF, SMEDAN, NDE and ITF, to mention a few. Therefore, as in previous studies, this research sought to ascertain the moderating role of entrepreneurial support as a tool for strengthening venture creation activities. Therefore, the authors hypothesized H2: entrepreneurial support moderates the relationship between self-efficacy and venture creation such that high-level entrepreneurial support would strengthen the relationship between the self-efficacy and venture creation activities of Nigerian graduates and vice versa.

3. Research Methodology

This study was conducted quantitatively using a cross-sectional survey design method. Data were randomly collected using a questionnaire that was administered to graduate beneficiaries of the GEF program. Details of measurements, sampling, data collection and the procedure of analysis are discussed in the subsequent section.

Research Questionnaire and Sampling

Instruments of analysis for this research were adapted from previous studies, in line with the suggestions of Colla et al. [110] and Ndofirepi [111]. The questionnaire had 3 sections: the first section related to the demographic information of the respondents; the second section contained screening questions; and the last section contained measurement items for variables, i.e., the dependent variable (DV) VC, independent variable (IV) ILEO, mediator (SELF) and moderator (ENTSP). The questionnaire had a total number of 57 questions. The measurements and their respective sources are presented in Table 1.

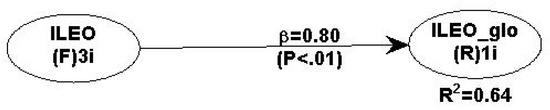

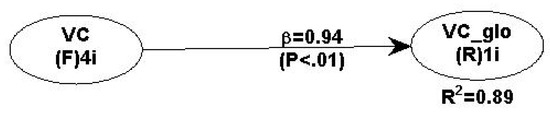

Two constructs (SELF and ENTSP) were measured as reflective, while ILEO and VC were measured as formative. Therefore, as a rule of thumb provided by Hair et al. [112] and Ramayah et al. [113] regarding formative measures, an extra question in the form of a “global single item measurement”, also referred to as a “marker variable”, was added to each of the constructs in accordance with the formative measurement guidelines [70,71,114,115]. This will provide a basis for redundancy analysis where the formatively measured construct ranked as an exogenous latent variable predicts constructs operationalized by the reflective indicators, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Based on the criteria, Hair et al. [112] suggested that the result of the path coefficient connecting the two constructs should have a minimum convergent validity of 0.70, which is equivalent to R2 = 0.64. The result met the criteria, as shown in Figure 2 (β = 0.80, R2 = 0.64, p < 0.01) and Figure 3 (β = 0.94, R2 = 0.89, p < 0.01), meaning the indicators of the constructs contributed significantly to explaining the research model.

Figure 2.

Regression between ILEO and global single item measurement.

Figure 3.

Regression between VC and global single item measurement.

Accordingly, a 5-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree (5) to Strongly Agree (1) was adopted to measure the respondents’ level of agreement or disagreement on the activities leading to venture creation. The marker technique, as suggested by Fuller et al. [116] and Simmering et al. [117], was applied to help address common method variance (CMV).

The sample size of the study was determined as 160 using the inverse square root method, as recommended by Kock and Hadaya [118] when using PLS-SEM. However, 320 questionnaires were distributed to graduates under the GEF program, and 291 responses were found to be usable. The respondents were randomly selected from a list of beneficiaries under the 2017 GEF intervention. They were contacted for consent through their phone numbers and locations displayed on the list. However, the first attempt using WhatsApp transmission failed due to a poor level of response. Therefore, as suggested by Sekaran [119], the conventional method was employed since there was a register of their addresses on the list. A summary of the questionnaire administration is shown in Table 2.

With the view that the study aimed to address the mechanism and contingency of the effect through mediation and moderation analysis, (i) the transmittal method under the explicit procedure of testing the indirect effect was employed to analyze the mediating effect, as recommended by Rungusanatham et al. [120]; (ii) the disjointed two-stage method under the two-stage approach that has been recommended for formative measures was used to assess the moderating effect, in line with the provisions of Ramayah et al. [113] and Sarstedt et al. [71]. This approach has been frequently used by studies that analyzed mediating and moderating relationships [121,122,123].

In addition, multiple regression in the PLS-SEM technique using WarpPLS-7 software was used for the assessment. The measurement model was determined through the “Factor-Based PLS” algorithm under the default “stable 3”, while the structural model was analyzed with Warp 3 PLS algorithms. Consistent with Kock [124,125], the path coefficients and p-values were computed via nonlinear relationships which provide full estimates of latent variables’ scores and account for the measurement error, in addition to the software’s advantages of pre-processing, standardizing data and reporting full collinearity through the variance inflation factors (VIFs) that double for controlling CMV.

Some studies that tested similar hypothesized relationships using PLS-SEM include Alvarez-torres [74], Brändle et al. [75], Nakku et al. [10], Kannadhasan et al. [89], Rasoolimanesh et al. [126] and Yazeed et al. [127].

Table 1.

Constructs’ measurements and sources.

Table 1.

Constructs’ measurements and sources.

| S/N | Constructs | Number of Items | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Venture creation (VC) HOC | 29 | Gatewood et al. [9] |

| (a) | Gathering market information (GMI) LOC | (6) | |

| (b) | Estimating potential profits (EPP) LOC | (4) | |

| (c) | Finishing groundwork for products (FGPS) LOC | (3) | |

| (d) | Developing structure of the company (DSC) LOC | (7) | |

| (e) | Setting up business operations (SBO) LOC | (9) | |

| 2. | Entrepreneurial orientation (ILEO) HOC | 10 | Bolton and Lane [6] Satar and Natasha [128] |

| (a) | Innovativeness (INNOV) LOC | (4) | |

| (b) | Risk taking (RISK) LOC | (3) | |

| (c) | Proactiveness (PROAC) LOC | (3) | |

| 3. | Self-efficacy (SELF) LOC | 5 | Szeli et al. [129] |

| 4. | Entrepreneurial support (ENTSP) LOC | 5 | Kazumi and Kawai [97], Malebana [130] Shinnar [131] |

Notes. HOC = higher-order constructs. LOC = lower-order constructs.

Table 2.

Summary of questionnaire administration.

Table 2.

Summary of questionnaire administration.

| Instruments | Frequency (f) | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution | 320 | 100 |

| Incomplete | 29 | 9.06 |

| Retained | 291 | 90.94 |

4. Result

4.1. Respondents’ Demographic Information

The demographic characteristics of the respondents were collected and analyzed with the aid of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 26) software, as shown in Table 3. The result shows that respondents within the age brackets of 20 to 30 years, 24 to 26 years, 27 to 30 years, 31 years and above and undisclosed accounted for 11.3%, 35.1%, 40.5%, 12.7% and 0.3%, respectively. Male respondents accounted for 69.4%, while females accounted for 30.6%. Respondents that were single, married, divorced and undisclosed accounted for 83.8%, 15.5%, 0.3% and 0.3%, respectively. Respondents that attended university, a polytechnic, other affiliations and undecided accounted for 77.7%, 18.9%, 3.1% and 0.3%, respectively. Respondents with a bachelor’s degree accounted for 74.9%, Higher National Diploma (HND) holders accounted for 16.8%, others accounted for 7.6% and undisclosed level of education accounted for only 0.7%. A total of 96.9% of the respondents agreed that “yes”, they have prior entrepreneurial experience in venture start-up activities, while 3.1% disagreed that “no”, they do not have prior entrepreneurial experience in venture start-up activities.

Table 3.

Respondents’ demographic details.

4.2. Non-Response Bias and Common Method Variance

As argued by Fuller et al. [116], it is not always automatic for survey research to encounter common method variance (CMV) or bias due to data originating from the same respondents. However, the marker technique, as suggested by Ali et al. [72], Chin et al. [132], Fuller et al. [116] and Simmering et al. [117], was applied using a global single item in the formative measures prior to data collection. Additionally, with the understanding that CMV only influences significant levels of bias when measures have very high or extremely low levels of internal consistency [72], the results of the analysis depict that no near-perfect reliabilities existed, correlations were not too magnified and inflated relationships were not detected from the research model. Thus, this indicates that there is no potential problem of CMV in the research model (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Reliability and convergent validity result.

Moreover, the inner model was not found to influence the outer model to a very large extent that could have increased collinearity. This is because the result of the variance inflation factors (VIFs), as shown in Table 5, was less than the conservative value of 5 and also less than the ideal value of 3.3 that is considered acceptable based on Kock [125]. Similarly, using the average full collinearity variance inflation factor (AFVIF) method to check for CMV, the AFVIF obtained was 2.753, still below the ideal 3.3 cut-off point and acceptable based on Kock [125]. This further suggests that there was no potential threat of CMV, and that multicollinearity was not an issue in this research.

4.3. Assessment of Measurement Model

Consistent with Hair et al. [112,114], the measurement model was assessed based on indicator collinearity, convergent validity, statistical significance and the relevance of the indicator weights. In stage 1, the following indicators did not met the criteria for loadings (0.708) and were removed based on the guidelines by Hair et al. [112]: DSC1, DSC2, SBO1, SBO2, SBO3, INNOV1 and RISK2. In addition, the construct “FGPS” could also not scale the discriminant validity (heterotrait-monotrait, HTMT) assessment (0.85 and 0.90) based on Henseler et al. [133] and was therefore removed from the model, in line with the criteria of Sarstedt et al. [71]. The slight adjustments corrected the model with satisfactory outer estimates, and thereafter, it was reanalyzed in stage 2 to conform the criteria of Becker et al. [70]. Details of the outer model assessment result can be seen in Appendix A, Figure A1 and Figure A2 for stage 1 and stage 2, respectively.

Redundancy analysis, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, indicated the respective constructs had convergent validity greater than 0.70, which is considered satisfactory based on Hair et al. [112] and Sarstedt et al. [71]. The VIF result was below 5 and less than the ideal value of 3.3, which is satisfactory based on Hair et al. [112] and Kock [125,134]. The result of the average full collinearity (AFVIF = 2.666) was also within the acceptable threshold below the ideal value of 3.3 and also less than the conservative value of 5, as suggested by Kock [125].

All the indicators’ weights were found to be significant at p < 0.05, and their outer loadings were all greater than 0.5, which also met the criteria of Hair et al. [112]. Therefore, it can be deduced that the research model fulfilled the requirement of a formative measurement model. Details of the measurement model can be seen in Table 5.

Table 5.

Measurement model result.

Table 5.

Measurement model result.

| HOC | LOC | Beta Value (R-Squared Value) | VIF | Full Collinearity VIF | Weights | Convergent Validity | t-Value Weights | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC | lv_GMI | 0.941 (0.886) | 2.552 | 3.089 | 0.296 | 0.876 | 5.295 | <0.001 | [0.187, 0.406] | 0.259 |

| lv_EPP | 2.241 | 2.428 | 0.284 | 0.840 | 5.065 | <0.001 | [0.174, 0.394] | 0.238 | ||

| lv_DSC | 2.282 | 2.428 | 0.284 | 0.842 | 5.076 | <0.001 | [0.175, 0.394] | 0.239 | ||

| lv_SBO | 2.656 | 3.260 | 0.298 | 0.882 | 5.331 | <0.001 | [0.188, 0.408] | 0.263 | ||

| ILEO | lv_INNOV | 0.771 (0.594) | 2.185 | 2.394 | 0.383 | 0.883 | 5.161 | <0.001 | [0.275, 0.491] | 0.338 |

| lv_PROAC | 2.547 | 2.637 | 0.379 | 0.874 | 5.143 | <0.001 | [0.271, 0.487] | 0.332 | ||

| lv_RISK | 2.139 | 2.331 | 0.378 | 0.873 | 5.340 | <0.001 | [0.270, 0.487] | 0.330 |

Note. HOC = Higher-order construct. LOC = Lower-order construct. VIF = Variance inflation factors. VC = Venture creation. ILEO = Individual level entrepreneurial orientation. p-values are based on a one-tailed test.

4.4. Assessment of Structural Model

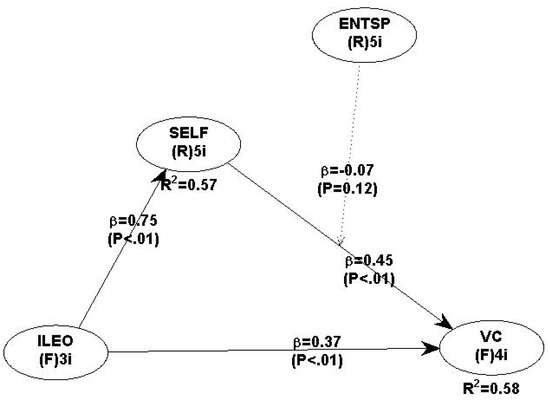

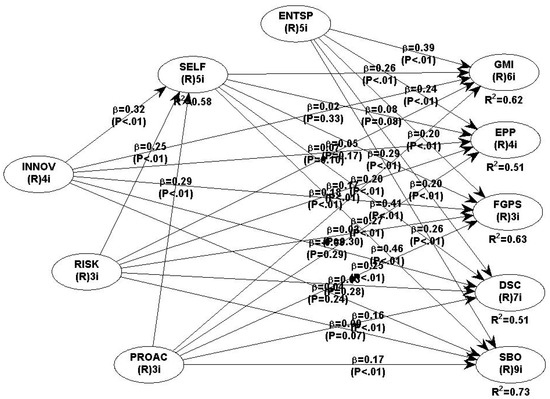

The structural model, as shown in Figure 4, was assessed based on the collinearity between constructs, the significance and relevance of the hypothesized paths (indirect effect and interaction effect), the adjusted R2 coefficient, the effect size (f2) and the predictive relevance (Q2) (e.g., Hair et al. [112], Sarstedt et al. [71] and Ramayah et al. [113]). The result of the path coefficients of the inner model shows no issue of multicollinearity because all the VIFs were less than 5, and therefore considered acceptable based on Hair et al. [112] and Kock [120]. On one hand, the result of the hypothesized indirect effect was found to be significant (β = 0.45, p < 0.05), with a path coefficient that was partially supported. On the other hand, the result of the hypothesized moderating effect was found to be negative and insignificant (β = −0.068, t = −1.170, p < 0.05), with a path coefficient that was not supported. In addition, the result of the structural model prediction through the explained variance (R2) was 0.584 and therefore considered large based on the criteria of Kock [120] and Cohen [135]. Similarly, result of the predictive relevance (Q2 = 0.660) was found larger than zero indicating the model has predictive relevance of the endogenous construct that supports the PLS paths, e.g., Hair et al [114]. Details of the R2 and Q2 are shown in Table 6. The effect size (f2 = 0.344) for mediation can be interpreted as medium based on the criteria of Kock [120] and Cohen [135]. Conversely, the f2 result for the moderation effect was 0.037, depicting a small effect size based on the recommendations of Kock [120], and Cohen [135]. Additional information on the paths analysis can be seen in Table 7.

Figure 4.

Structural model result.

Table 6.

Latent variables’ coefficient of determination (R2) and predictive relevance (Q2).

Table 7.

Path analysis result for mediating and moderating effects.

Accordingly, the result of the inner model indices indicates the model has good model fitness that supports the hypothesized direction of causality based on the criteria of Kock [120], i.e., the average path coefficient (APC = 0.410, p < 0.001), the average R-squared (ARS = 0.575, p < 0.001), the average adjusted R-squared (AARS = 0.572, p < 0.001) and the average block VIF (AVIF = 2.661) are acceptable when ≤5, ideally ≤ 3.3; the average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF = 2.753) is acceptable when ≤5, ideally ≤ 3.3; the Tenenhaus GoF (GoF = 0.670) is large when ≥0.36; Sympson’s paradox ratio (SPR = 0.750) is acceptable when ≥0.7; the R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR = 0.969) is acceptable when ≥0.9; the statistical suppression ratio (SSR = 1.000) is acceptable when ≥0.7; and the nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR = 0.750) is acceptable when ≥0.7.

4.4.1. The Mediating Effect Assessment

The mediating effect assessment was conducted by following the causal steps recommended by Hair et al. [112], Hayes and Rockwood [122] and Hayes and Scharkow [123]. The result shows the presence of a mediating effect because the indirect path was found to be significant. Figure 4 presents the result of the full research model showing that the indirect effect was partial mediation. The indirect effect was also found to be the complementary type of mediation when applying the criteria of Hair et al. [114]. This is because the path coefficient of the indirect effect is positive and significant (β = 0.45, p < 0.05), in the same way the direct effect is also positive and significant (β = 0.37, p < 0.05), and points to the same direction, which makes it partial and complementary mediation. Therefore, it can be deduced that the hypothesized relationship of ILEO → SELF → VC was mediated but partially, and this conforms to the criteria of Aguinis et al. [136]. Details of the path analysis are shown in Table 7.

Therefore, the result can be interpreted as follows: self-efficacy acquires only a part of the indirect effect and total effect, similar to the direct effect, as shown in Figure 4. Therefore, this confirms that a mediator variable must be causally located with values closer to zero when it is held constant as opposed to when it is compared through the mediator itself [122,136]. The result also supports Kock [137] and Zhao et al. [92], who argued that partial mediation occurs when the p-value of both paths is found to be significant. By implication, the initial hypothesis (H1) that states “the greater the level of self-efficacy held by Nigerian graduates, the more it positively mediates the relationship between individual-level entrepreneurial orientation and venture creation activities” is accepted based on this finding.

Furthermore, the variance accounted for (VAF = (a × b)/((a × b) + c’)) was used to determine the size of the indirect effect and the total effect through the path coefficients. The computation was conducted by multiplying the path coefficients of ILEO → SELF, β = 0.752, and of SELF → VC, β = 0.445. Therefore, the indirect effect was obtained as a product of 0.752 × 0.445 = 0.335. In turn, the total effect was determined by adding the direct effect and the indirect effect, i.e., 0.709 + 0.335 = 1.044. Therefore, VAF = 0.335 ÷ 1.044 = 0.32, meaning that 32% of the variance of graduates’ VC activities is explained by ILEO through SELF. The VAF obtained (32%) supported our finding because a VAF greater than 20% but less than 80% indicates partial mediation based on the recommendations of Ramayah et al. [113].

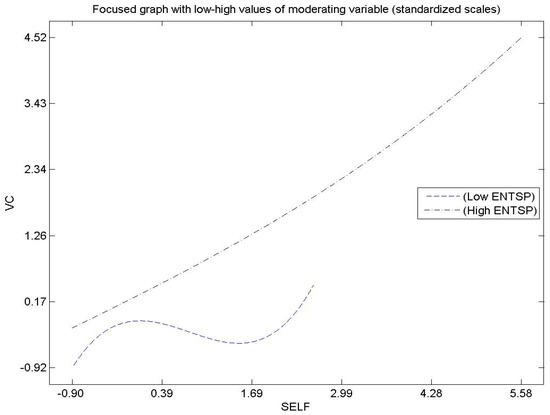

4.4.2. The Moderating Effect Assessment

Figure 4 displays the result of the research model showing the interaction term that connected the moderator with two other endogenous constructs (SELF and VC). Even though the hypothesis sought to ascertain the moderating role of ENTSP in relation to SELF and VC, the result found was negative and insignificant (β = −0.068, t = −1.170, p < 0.05). This indicates that the interaction term through ENTSP negatively impacted the relationship between SELF and VC. As such, it can be interpreted that no moderating effect was found based on the criteria of Dawson [138]. Details of the path analysis are shown in Table 7.

5. Discussion

This study examined the perspectives of entrepreneurial orientation (ILEO) in relation to venture creation (VC) through the mediating role of self-efficacy (SELF) and the moderating effect of entrepreneurial support (ENTSP) among graduates. The study was conducted through the formative measurement approach by applying the reflective/formative type II method (e.g., Sarstedt et al. [71]). In stage 1, the result of the outer model, as presented in Table 5, was assessed through the loadings, reliability and convergent validity. For each indicator, loadings greater than 0.708 were considered, and those below this value (e.g., DSC1, DSC2, SBO1, SBO2, SBO3, INNOV1 and RISK2) were removed, in order to achieve a sufficient degree of indicators’ variance (e.g., Hair et al. [112]).

Internal consistency was assessed via Cronbach’s alpha, Dijkstra’s rho_A and composite reliability in accordance with Sarstedt et al. [71]. The result, as shown in Table 4, indicates that the reliability of the measures ranged between 0.70 and 0.90, which is considered satisfactory and good, based on Hair et al. [112]. This indicates the items were non-problematic and not redundant because they received a desirable pattern of response. Convergent validity was assessed through the average variance extracted (AVE), as shown in Table 4. All items in Table 4 met AVEs above 0.50, indicating the constructs explain more than 50% of the variance in their items, as opined by Hair et al. [112]. In addition, the discriminant validity (heterotrait-monotrait, HTMT) was assessed based on the criteria of Henseler et al. [133]. The output of the model’s estimate showed that only one construct, “FGPS”, scored higher than the threshold (0.85, 0.90) and was removed in accordance with the provisions of Sarstedt et al. [71].

In stage 2, the model was reanalyzed as in stage 1, and the results obtained were satisfactory because the loadings, reliability and convergent validity satisfied the criteria recommended by Ali et al. [72], Hair et al. [112] and Sarstedt et al. [71]. Then, a redundancy test was performed in line with the provisions of Kock and Lynn [134], e.g., ILEO → ILEO_glo, and VC → VC_glo. The results of the analysis, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, indicate each of the constructs had a convergent validity score greater than 0.70, which is satisfactory based on Hair et al. [112]. This indicates there was no potential issue of collinearity in the research model, and this provides support for validating ILEO as a reflective/formative type II second-order construct.

The result of the hypothesized relationships (indirect effect, interaction effect) is shown in Figure 4. For instance, the first hypothesis sought to ascertain the indirect effect of self-efficacy in the relationship between ILEO and VC. The result of the mediation test was found to be positive and significant because there was a partial and complementary mediating effect. This meant that self-efficacy had a positive effect on VC (β = 0.45, p < 0.05, indirect path), and ILEO was positively related to VC (β = 0.37, p < 0.05, direct path). This finding supports the first research hypothesis (H1) that states “the greater the level of self-efficacy held by Nigerian graduates, the more it positively mediates the relationship between individual-level entrepreneurial orientation and venture creation activities”. On the other hand, the second hypothesis sought to ascertain the moderating role of ENTSP in relation to SELF and VC. The result obtained shows ENTSP negatively impacted the relationship between SELF and VC (β = −0.068, t = −1.170, p < 0.05). This invariably means the interaction term through ENTSP did not moderate the relationship between SELF and VC. As such, it did not support the second hypothesis (H2) that states “entrepreneurial support moderates the relationship between self-efficacy and venture creation such that high-level entrepreneurial support would strengthen the relationship between the self-efficacy and venture creation activities of Nigerian graduates and vice versa.” The interaction plot is presented in Appendix A Figure A3.

In light of these findings, this study unveils that the indirect relationship between individual-level entrepreneurial orientation and venture creation through self-efficacy was positive and significant but negatively moderated by entrepreneurial support. This implies not all instances of ILEO will result in VC through SELF as ILEO can directly lead to VC, and vice versa. Meanwhile, the interaction term (ENTSP) that was expected to strengthen the relationship between SELF and VC only negatively impacted it. Therefore, graduates are advised to maintain the status quo by developing persistence to increase their confidence level in undertaking venture creation activities, while authorities concerned with managing intervention programs should find a way of incorporating financial, non-financial and incubation services in the scheme of training young graduate entrepreneurs, because this will help support the venture start-up process [1,10,12,99,139].

This is similar to the opinion held by Weiss et al. [106], which also found university seed funding negatively impacted students’ support for new venture creation in Switzerland.

As mentioned earlier in Section 2, there is a shortage of studies that look into this type of relationship. Even the related studies were mostly conducted in countries in Asia, Europe and America, with a few from Africa. Some of them include Puni et al. [90], Neneh [1], Salami [93], Marshall et al. [52], McGee et al. [62], Piperopoulos and Dimov [94], Kannadhasan et al. [89] and Chen and He [91], which explored the mechanism of the effect through self-efficacy. Others include Shirokova et al. [103], Weiss et al. [106], Anwar et al. [11], Guo et al. [104], Shi et al. [105], Houque [13], Li et al. [12] and Nakku et al. [10], which analyzed the moderating effect of support. However, the research findings are at variance with some previous findings such as those of Anwar et al. [11], Neneh [1], Li et al. [12], Shi et al. [105], Hoque [13] and Nakku et al. [10], which found a positive and significant moderating effect. However, this study’s findings corroborate those of Shirokova et al. [103], Guo et al. [104] and Weiss et al. [106] on account of the negative interaction effect. Accordingly, the result of the mediation test is similar to that of previous studies such as Puni et al. [90], Chen and He [91], Marshall et al. [52], Zhao et al. [73], Neneh [1], Salami [93], Piperopoulos and Dimov [94], Kannadhasan et al. [89] and McGee et al. [62], and corroborates the result of Kannadhasan et al. [89], which also found a partial mediating effect.

Based on this evidence and with particular reference to the inconsistencies of findings on the moderating effect, future studies can use the research model in another setting or context different from the one investigated. In addition, the relationship can be re-examined with the inclusion of intervening variables to see chances of improving the moderating relationships, as suggested by Dawson [138]. This is a similar position to that maintained by Spector and Brannik [140] on the use of statistical control variables that are capable of providing accurate estimates of predictors’ relationships that underlines a theoretical framework. This will yield a sufficient degree of understanding the causal sequence of interaction between variables of the hypothesized relationships, e.g., ENTSP × SELF → VC.

6. Conclusions

This study advances the understanding on the imperatives of entrepreneurial orientation, self-efficacy and entrepreneurial support in relation to venture creation activities. Conducting the study from the formative approach, it was designed to establish a framework that will educate younger generations of persons such as students on the steps, preparations and actions required to assume post-graduation responsibilities through self-reliance. This was informed following the rising problems of graduates’ unemployment and the inability to secure a job after graduation [2,17,100,141]. However, the effort of the government towards addressing this menace has been acknowledged through various intervention schemes from agencies such as the CBN, BOI, GEF, SMEDAN, NDE and ITF [22,29,34,35,36,37,38]. As such, this study aimed to commemorate this effort by empirically investigating graduates’ entrepreneurial orientation in relation to venture creation through the mediating and moderating roles of self-efficacy and entrepreneurial support as a basis of becoming self-reliant.

This is based on the understanding that governments in present times have subscribed to the campaign of self-reliance as the most efficient way of addressing unemployment problems [1]. Therefore, considering that, for one to be self-reliant, he/she needs to partake in some entrepreneurship activities, and this requires a specific medium of practice known as a venture, enterprise, company or organization. This means young graduates that chooses to become entrepreneurs will be required to set up their respective enterprises after graduation. In this regard, this study explored start-up actions from beneficiary graduates of the GEF intervention program in the quest to gain practical knowledge that demonstrates the venture creation process from an experienced background.

The findings of this study show that developing personal self-efficacy is an essential attribute for enterprising since it was found to mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and venture creation activities. Therefore, to maintain the status quo, graduates should develop persistence that, in turn, drives confidence for engaging in such an activity (e.g., Cardon and Kirk [44]). On the other hand, the moderating role of entrepreneurial support only negatively impacted the relationship between self-efficacy and venture creation, an indication that there is no moderating effect on the observed relationship. Based on these facts, the researchers suggest testing the research model in a different setting or context distinct from the one investigated. Equally, future studies can re-examine the relationship with the inclusion of intervening variables (e.g., experience). This will pave the way to seeing changes in the moderating effect between graduates with high-level experience and those with low-level experience on entrepreneurship activities.

As such, this study conceptualizes that venture creation among graduates is informed by individual-level entrepreneurial orientation through the mediating role of self-efficacy, given that the interaction effect between self-efficacy and venture creation was negatively impacting. This study contributes theoretically and practically by integrating the concept of self-efficacy in relation to an entrepreneurial orientation model and indicators of start-up actions on venture creation (VC). This demonstrates that individual-level entrepreneurial orientation (ILEO) is an important consideration for understanding VC activities both indirectly, ILEO → SELF → VC, and directly, ILEO → VC. This study also found support for validating ILEO as a reflective/formative type II second-order construct.

Therefore, policy makers and managers of intervention programs should consider incorporating aspects of financial, non-financial and incubation services into the modalities of training graduate entrepreneurs. This is because previous studies such as Li et al. [12] and Otache [99] are of the opinion that if governments prioritize support mechanisms through incubation facilities, this will bring about diversification of opportunities across various forms of services, production, manufacturing, agricultural processing, etc. In addition, Bezeau et al. [139] also emphasized the non-financial aspect to cover advisory roles, job training, networking and management teams, as this will help sustain the survival of nascent start-ups. Meanwhile, the aspect of financial support should be provided in good time so as to help facilitate the new start-up process [106,142]. There is no doubt that taking these steps will provide a conducive atmosphere for school graduates to establish businesses and become self-reliant whilst also containing unemployment problems.

In this regard, tertiary institutions and incubation centers where students and graduates are trained to become entrepreneurs need to intensify ways of enhancing these attributes in students and graduates. For instance, this can be achieved at the incubation centers where graduates can be tutored on the success stories of some famous entrepreneurs such as Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Larry Page, Bill Gates, Henry Ford, Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Ma as inspiration to increase their level of persistence towards actualizing their entrepreneurial dreams.

Therefore, while this study provides a new vision and, by extension, confirms existing knowledge in similar areas of research, it equally presents some limitations that steer the direction of future studies.

7. Limitations and Recommendations

The limitation of this study lies in the chosen method of conducting the research, which did not pave the way for generalizing the research findings. However, we suggest future research to conduct a longitudinal survey that will enhance the understanding of the phenomena and establish the basis for generalizing the results. This will give future researchers the chance to evaluate graduates’ start-up actions at the first phase of admission into training and equally re-evaluate their start-up preparations at the tail end of completing the training program. A similar approach was used by Weiss et al. [106] and McGee et al. [62] to generalize their findings following the methods of a biannual survey and a multi-wave survey that were used by the former and latter, respectively.

Therefore, the result of this study shows that venture creation among graduates is informed by individual-level entrepreneurial orientation (innovativeness, risk taking and proactiveness) through the mediating role of self-efficacy, given that the interaction effect (entrepreneurial support) between self-efficacy and venture creation was found to be negative. The younger generation of graduates should maintain the status quo by developing persistence to add to their confidence level for undertaking venture creation activities. On the other hand, intervention agencies should initiate effective entrepreneurial support tools that will cover financial, non-financial and incubation services in an attempt to boost graduates’ venture creation activities.

Author Contributions

S.R.N.-A.: preparation, investigation, original draft writing, methodology, data collection, software and formal analysis. N.H.A.: supervision, conceptualization, writing, reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to some reasons that the study forms part of the author’s thesis, and have initially received a formal introductory letter from the institution which was circulated to all stakeholders concerned in the study, before data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Bank of Industry (2020), Graduate Entrepreneurship Fund, https://www.boi.ng/graduate-entrepreneurship-fund/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the efforts of some personalities such as Abubakar Suleiman of the Department of Management and Information Technology, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi, Nigeria, for kindly assisting in the research, especially during the data analysis stage. Equally, we appreciate Nazir Mustapha, Dalong Langkat, Usman Abdullahi and Sadam Ahmad who assisted during the data collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Measurement model stage 1. Source: PLS−SEM output.

Figure A2.

Measurement model stage 2. Source: PLS−SEM output (2021).

Figure A3.

Interaction plot for the negative and insignificant interaction effect. Source: PLS−SEM output (2021).

References

- Neneh, B.N. Entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention: The role of social support and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 47, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosu, G.A. Dear Graduates Are You Still after White-Collar Jobs? Dailytrust: Abuja, Nigeria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Odewale, G.T.; Hani, S.H.A.; Migiro, S.O.; Adeyeye, P.O. Entrepreneurship education and students’ views on self-employment among international postgraduate students in universiti utara malaysia. J. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 22, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Simoes, N.; Crespo, N.; Moreira, S.B. Individual Determinants of Self-Employment Entry: What Do We Really Know? J. Econ. Surv. 2016, 30, 783–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlqvist, J.; Wiklund, J. Measuring the market newness of new ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D.L.; Lane, M.D. Individual entrepreneurial orientation: Development of a measurement instrument. Educ. Train. 2012, 54, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Academy of Management Review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Motivational Processes—Self-Efficacy. John Wley & Sons Inc. 2009. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0836 (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Gatewood, E.J.; Shaver, K.G.; Gartner, W.B. A longitudinal study of cognitive factors influencing start-up behaviors and success at venture creation. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakku, V.B.; Agbola, F.W.; Miles, M.P.; Mahmood, A. The interrelationship between SME government support programs, entrepreneurial orientation, and performance: A developing economy perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 2–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; Tajeddini, K.; Ullah, R. Entrepreneurial finance and new venture success-the moderating role of government support. Bus. Strateg. Dev. 2020, 3, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ahmed, N.; Qalati, S.A.; Khan, A.; Naz, S. Role of Business Incubators as a Tool for Entrepreneurship Development: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Business Start-Up and Government Regulations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, A.S.M.M. Does Government Support Policy Moderate the Relationship Between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Bangladeshi SME Performance ? A SEM Approach. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2018, 6, 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bin Othman, M.F.; Nazariah, O.B.; Mohammed, I.S. Restructuring Nigeria: The Dilemma and Critical Issues. J. Bus. Soc. Rev. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 5, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kolade, O. Venturing under fire: Entrepreneurship education, venture creation, and poverty reduction in conflict-ridden Maiduguri, Nigeria. Educ. Train. 2018, 60, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzeagwu, U. Why IPOB Formed Eastern Security Network, by Kanu. The Guardian Nigeria News-Nigeria and World NewsNigeria—The Guardian Nigeria News–Nigeria and World News. The Guardian. 2020. Available online: https://guardian.ng/news/why-ipob-formed-eastern-security-network-by-kanu/ (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Saanyol, T. Youths Represent 64 Per Cent of Unemployed Population in Nigeria―Atiku. Nigerian Tribune. 2021. Available online: https://tribuneonlineng.com/youths-represent-64-per-cent-of-unemployed-population-in-nigeria-―-atiku/?utm_term=Autofeed&utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR2cCZSNZrfqGZoktYhNz5wL4KEj510I4DhW3C2D4vDWlLx86PPvls8Egbw#Echobox=1617947376 (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Sanyaolu, A. 26m Job Seekers Apply for Positions as NNPC Closes Recruitment Portal–The Sun Nigeria. The Sun News Paper. 2019. Available online: https://www.sunnewsonline.com/26m-job-seekers-apply-for-positions-as-nnpc-closes-recruitment-portal/ (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Stephen, I. Confronting Nigeria’s Unemployment Crisis-Punch Newspapers. Punch Newspaper. 2019. Unemployment. Available online: https://punchng.com/confronting-nigerias-unemployment-crisis/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- N. A. of N. Agency Report. Nigeria’s Unemployment Rate Hits 33.5 Per Cent by 2020–Minister|Premium Times Nigeria. Premium Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/328137-nigerias-unemployment-rate-hits-33-5-per-cent-by-2020-minister.html (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Owoeye, F. NBS: Nigeria’s Unemployment Rate Hits 33.3%—Highest Ever|TheCable. The Cable. 2021. Available online: https://www.thecable.ng/nbs-nigerias-unemployment-rate-hits-33-3-highest-ever (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Adefunke, A.; Adekunle, O.; Adesoga, D.; Olalekan, U. Social Innovation and Graduate Entrepreneurship in Nigeria. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 22, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarape, A. On the road to institutionalising entrepreneurship education in Nigerian universities. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2008, 7, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyebe, A.A. Entrepreneurship Education and Employment in Nigeria. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebiringa, T. Perspectives: Entrepreneurship Development & Growth of Enterprises in Nigeria. Entrep. Pract. Rev. 2012, 2, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting, O.E. Historical Analysis of Educational Policies in Colonial Nigeria from (1842–1959) and Its Implication to Nigerian Education Today. 2018. Available online: http://www.ijsre.com (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Uche, C.U. British Government, British Businesses, and the Indigenization Exercise in Post-Independence Nigeria. Bus. Hist. Rev. 2020, 86, 745–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertuna, Z.I.; Gurel, E. The moderating role of higher education on entrepreneurship. Educ. Train. 2011, 53, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egwu, I.L. Entrepreneurship Development in Nigeria: A Review. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 16, 01–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meager, N.; Martin, R.; Carta, E.; Davison, S. Skills for Self-Employment: Main Report Skills for Self-Employment Institute for Employment Studies UKCES Project Manager. 2011. Available online: www.ukces.org.uk (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Onuma, N. Entrepreneurship education in Nigerian tertiary institutions: A remedy to graduates unemployment. Br. J. Educ. 2016, 4, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Aminu, A. Characterising Graduate Unemployment in Nigeria as Education-job Mismatch Problem. Afr. J. Econ. Rev. 2019, VII, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Udo, B. Small, Medium Enterprises Account for 84 per Cent of Jobs in Nigeria. Premium Times Nigerian News Paper. Available online: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/business/business-news/215707-small-medium-enterprises-account-84-per-cent-jobs-nigeria.html (accessed on 7 June 2020).

- Hussaini, M. Poverty Alleviation programs in Nigeria: Issues and Challenges. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2017, 4, 717–720. [Google Scholar]

- Nkechi, A.; Ej, E.I.; Okechukwu, U.F. Entrepreneurship development and employment generation in Nigeria: Problems and prospects. Univers. J. Educ. Gen. Stud. 2012, 1, 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yahaya, D.H.; Geidam, M.M.; Usman, M.U. The Role of Micro Small and Medium Enterprises in the Economic Development of Nigeria 1 the Role of Micro Small and Medium Enterprises in the Economic Development of Nigeria. 2016. Available online: www.cardpub.org/jamar:jamar@cardpub.org (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- YEDP. Central Bank of Nigeria: YEDP. Central Bank of Nigeria. 2020. Available online: https://www.cbn.gov.ng/Devfin/yedp.asp (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- B. of I. BOI. Graduate Entrepreneurship Fund|Bank of Industry, Nigeria. Bank of Industry. 2020. Available online: https://www.boi.ng/graduate-entrepreneurship-fund/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Bank of Industry. Bank of Industry Shortlisted Candidates for Capacity Building Trianing Programme. Graduate Entrepreneurship Fund. 2020. Available online: https://www.boi.ng/downloads/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Shook, C.L.; Priem, R.L.; McGee, J.E. Venture creation and the enterprising individual: A review and synthesis. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Nikolaev, B.; Shir, N.; Foo, M.; Bradley, S. Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. Behavioral and cognitive factors in entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurs as the active element in new venture creation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakanastasi, E.; Karagiannaki, A.; Pramatari, K. Entrepreneurial Team Dynamics and New Venture Creation Process: An Exploratory Study Within a Start-Up Incubator. Spec. Collect.-Entrep. Teams 2018, 8, 2158244018781446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Kirk, C.P. Entrepreneurial passion as mediator of the self–efficacy to persistence relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 39, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenius, P.; Engel, Y.; Klyver, K. No particular action needed? A necessary condition analysis of gestation activities and firm emergence. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2017, 8, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.S.; Kreiser, P.M.; Donald, K.F.; Hornsby, J.S.; Eshima, Y. RECONCEPTUALIZING ENTREPRENEURIAL ORIENTATION. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1579–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.H.; Lee, J.-H. Entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial education and performance. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 12, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Miller (1983) revisited: A reflection on EO research and some suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 873–894. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00457.x (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive career theory at 25: Empirical status of the interest, choice, and performance models. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.E.; Creed, P.A.; Searle, J. The development and initial validation of social cognitive career theory instruments to measure choice of medical specialty and practice location. J. Career Assess. 2009, 17, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendling, E.; Sagas, M. An Application of the Social Cognitive Career Theory Model of Career Self-Management to College Athletes’ Career Planning for Life After Sport. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, D.R.; Meek, W.R.; Swab, R.G.; Markin, E. Access to resources and entrepreneurial well-being: A self-efficacy approach. J. Small Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, K.; Tiemann, I. Factors influencing university support for sustainable entrepreneurship: Insights from explorative case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gu, J. The Role of Entrepreneurial Passion and Creativity in Entrepreneurial Intention: A Hierarchical Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Entrepreneurial Support Programs. J. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 156–167. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/reader/234641310 (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- George, B.A. Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Theoretical and Empirical Examination of the Consequences of. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1291–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, T.; Hind, P.; Lawrence, J. Entrepreneurial orientation, Waynesian self- efficacy for searching and marshaling, and intention across gender and region of origin. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2019, 35, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a theory of planned behavior questionnaire. Res. Gate 2016, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Lunpkin, G.T. The Relationship of Personality to Entrepreneurial Intentions and Performance: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorostiaga, A.; Aliri, J.; Ulacia, I.; Soroa, G.; Balluerka, N.; Aritzeta, A.; Muela, A. Assessment of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Vocational Training Students: Development of a New Scale and Relationships With Self-Efficacy and Personal Initiative. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Gurau, C.; Torre, O. Creativity, self-efficacy, and small-firm performance: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]