It Is a Balancing Act: The Interface of Scientific Evidence and Policy in Support of Effective Marine Environmental Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

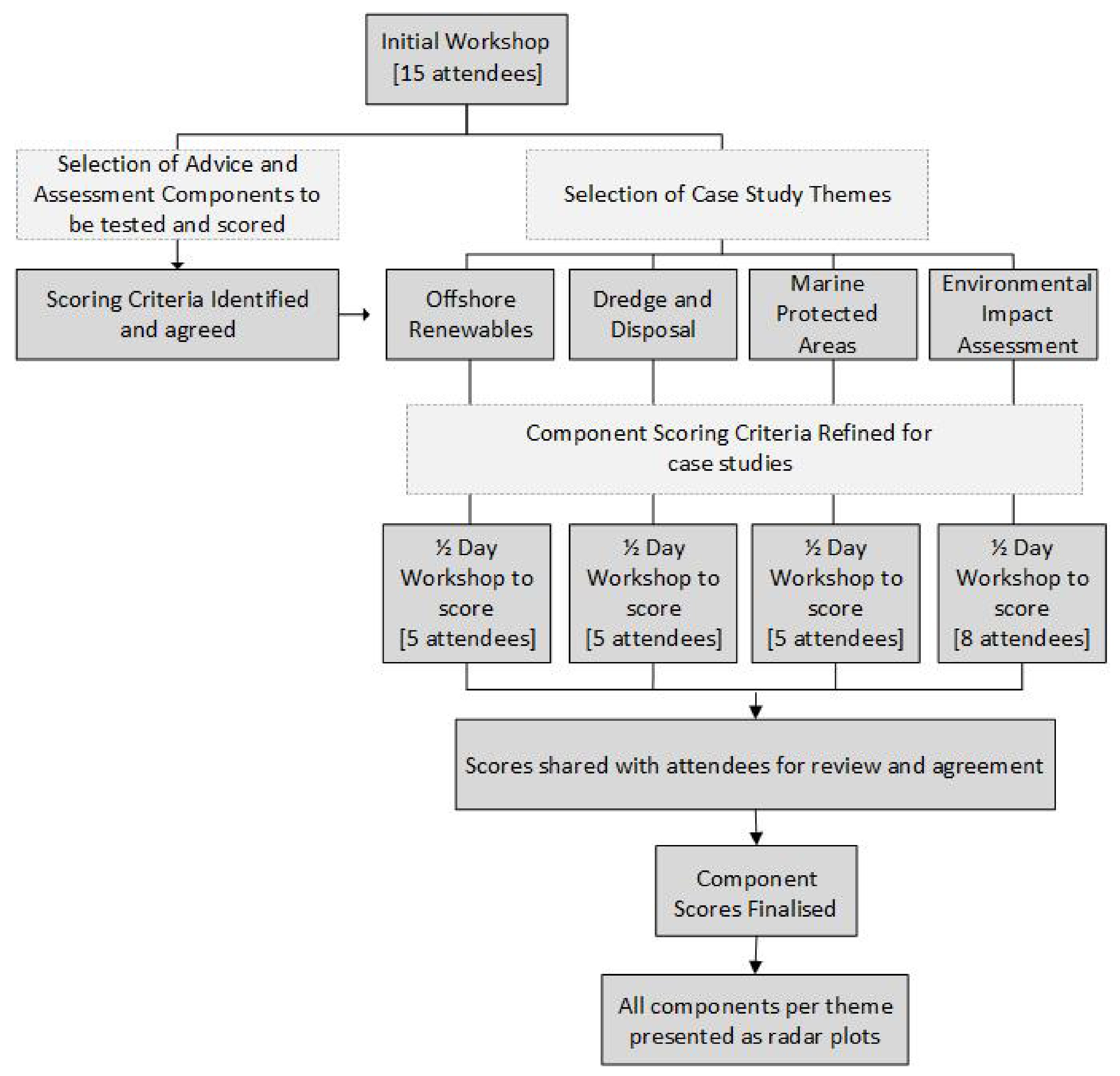

2. Materials and Methods

- -

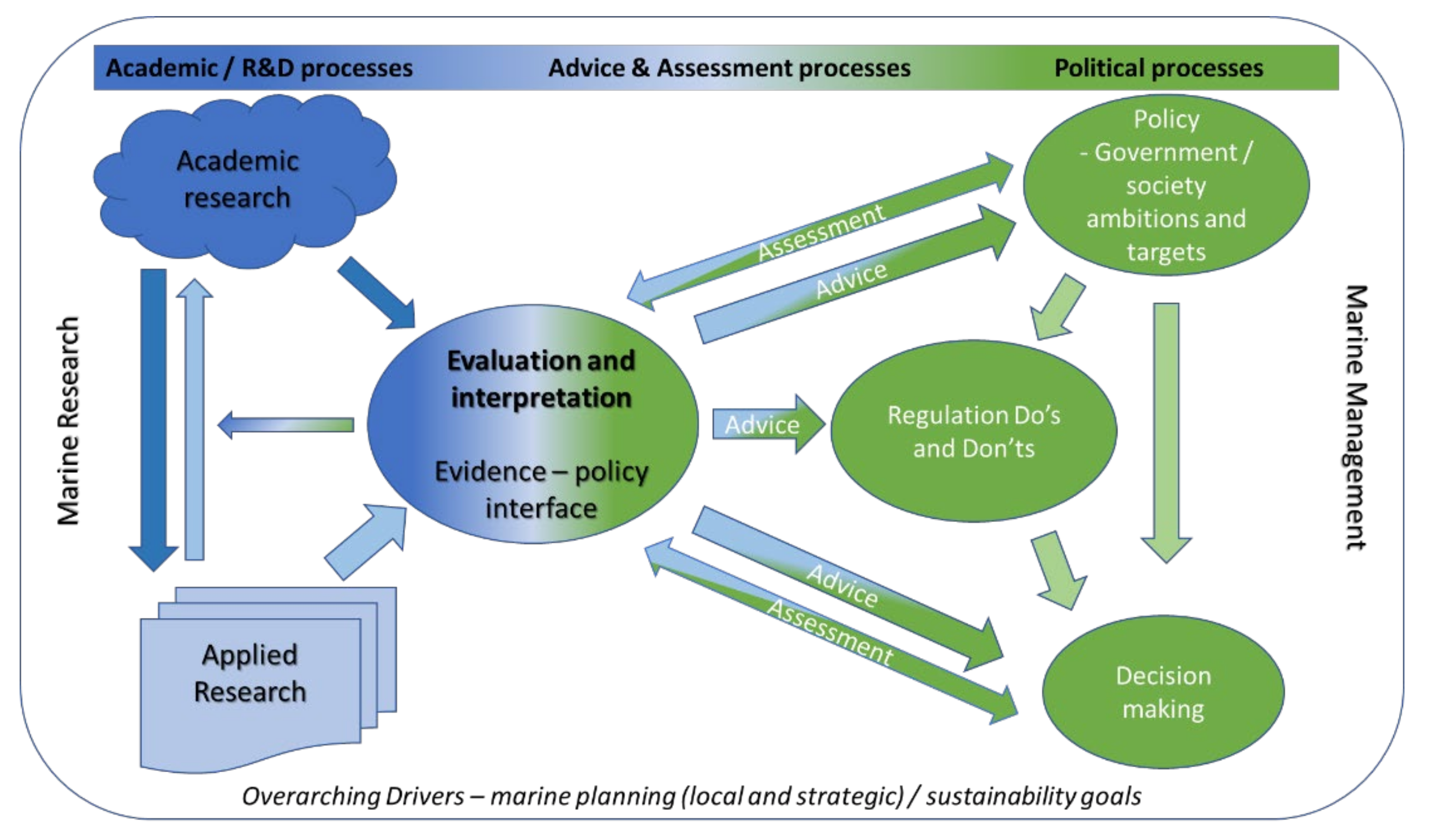

- Research to understand the natural environment applied to inform the sustainable use and development of natural resources.

- -

- Assessments provide either predictive or observed changes. Technical advice takes the outputs of research and assessments and translates these into meaningful outcomes to inform regulation and policy.

- -

- Monitoring/Evaluation to determine if changes have occurred and, if so, to what extent as well as the causes of such changes (and if attributed to human activities, what additional mitigation or intervention may be required).

- -

- Regulations which can both drive the need for evidence (e.g., state of the oceans assessments) and also use evidence as the basis for the need for legislation (e.g., microbead ban).

- -

- Policy which sets out the aims, objectives, and vision of the government, requiring an understanding of the natural environment, its value, and its uses for society.

3. Results: Case Studies

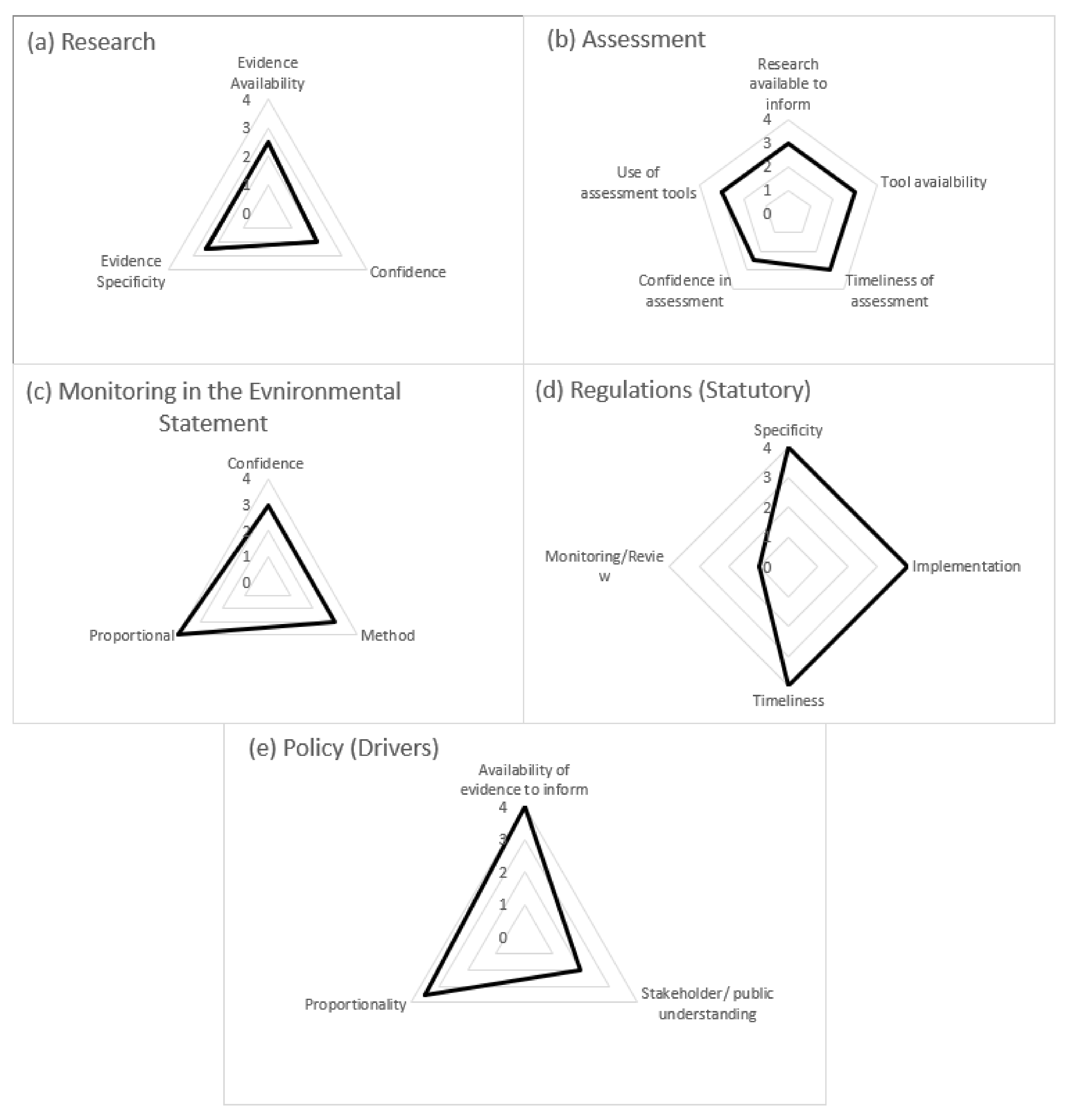

3.1. Environmental Impact Assessments

3.2. Dredge and Disposal Operations

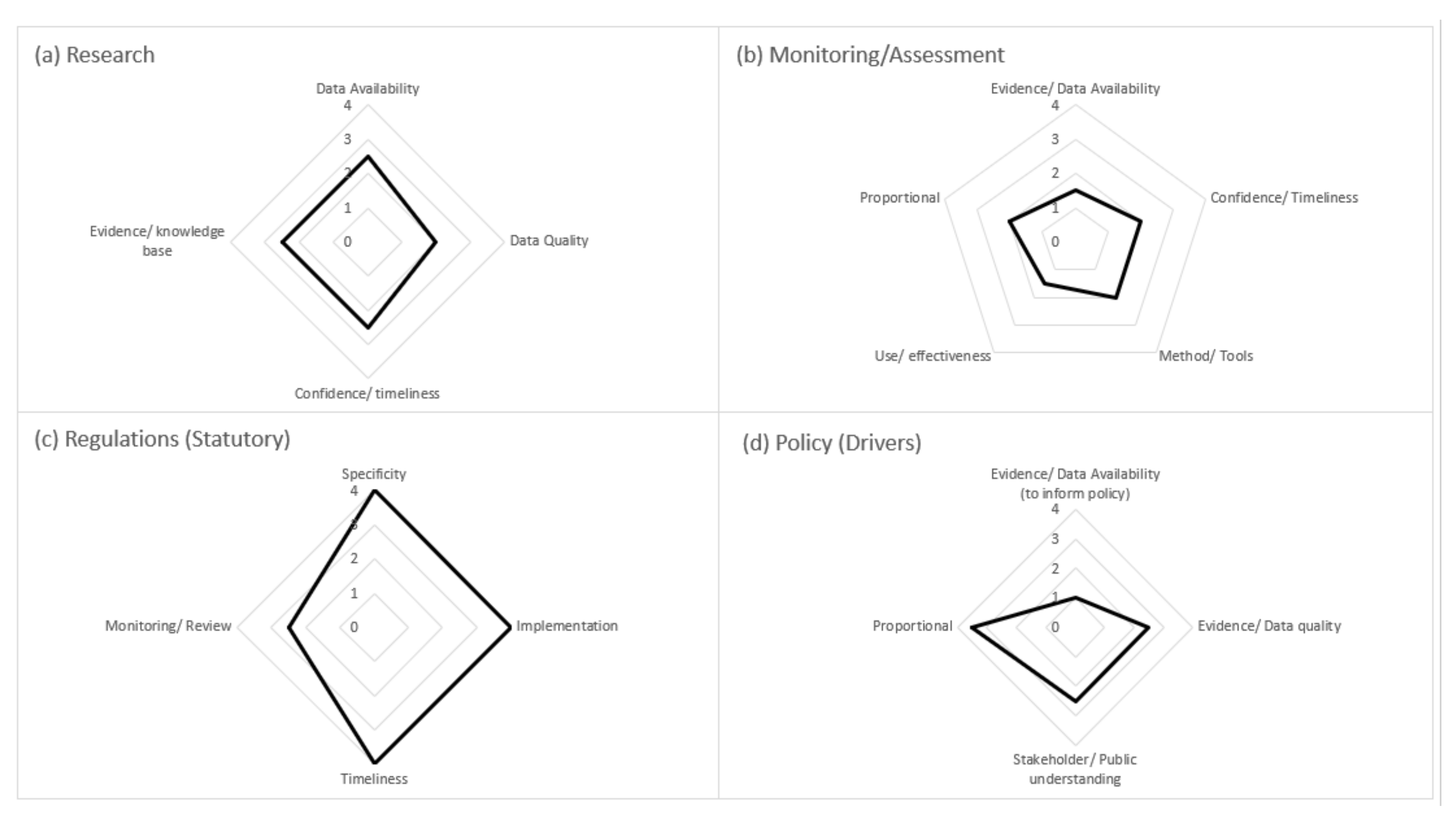

3.3. Marine Protected Areas

3.4. Offshore Renewable Energy Developments

4. Discussion

- Data accessibility: by having academia, industry and government share data platforms, with such platforms being more integrative for the combination of data sources and signposting to allow easier searches beyond the current situation.

- Streamline funding opportunities: using UK Research Council workshops and the Offshore Renewables Joint Industry Programme (ORJIP) as examples to call for scientifically robust policy and applied ideas in order to scope funding calls and then assess proposals.

- Driver and output alignment: to reduce unnecessary effort put into unwieldy reports which do not communicate the project and results effectively, but rather the provision of better/sharper products that allow the outputs to be more widely and consistently used and applied.

- Effective dissemination: by having round table discussions between advisors and regulators for an effective planning dialogue, leading to a more holistic approach to understanding and managing the marine environment.

- Ensure holistic approaches: to science, policy, regulation, and legislation to ensure the ecosystem-based approach to management is applied.

- Ensure Monitoring is hypothesis driven: and continue to monitor and assess new activities such as MPAs or floating offshore wind farms.

- Public engagement: so the public have a clearer understanding of why the government has certain policies and commitments, and how these interlink (i.e., the drive for increased offshore renewable energy production and the need to protect 30% of our seas).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

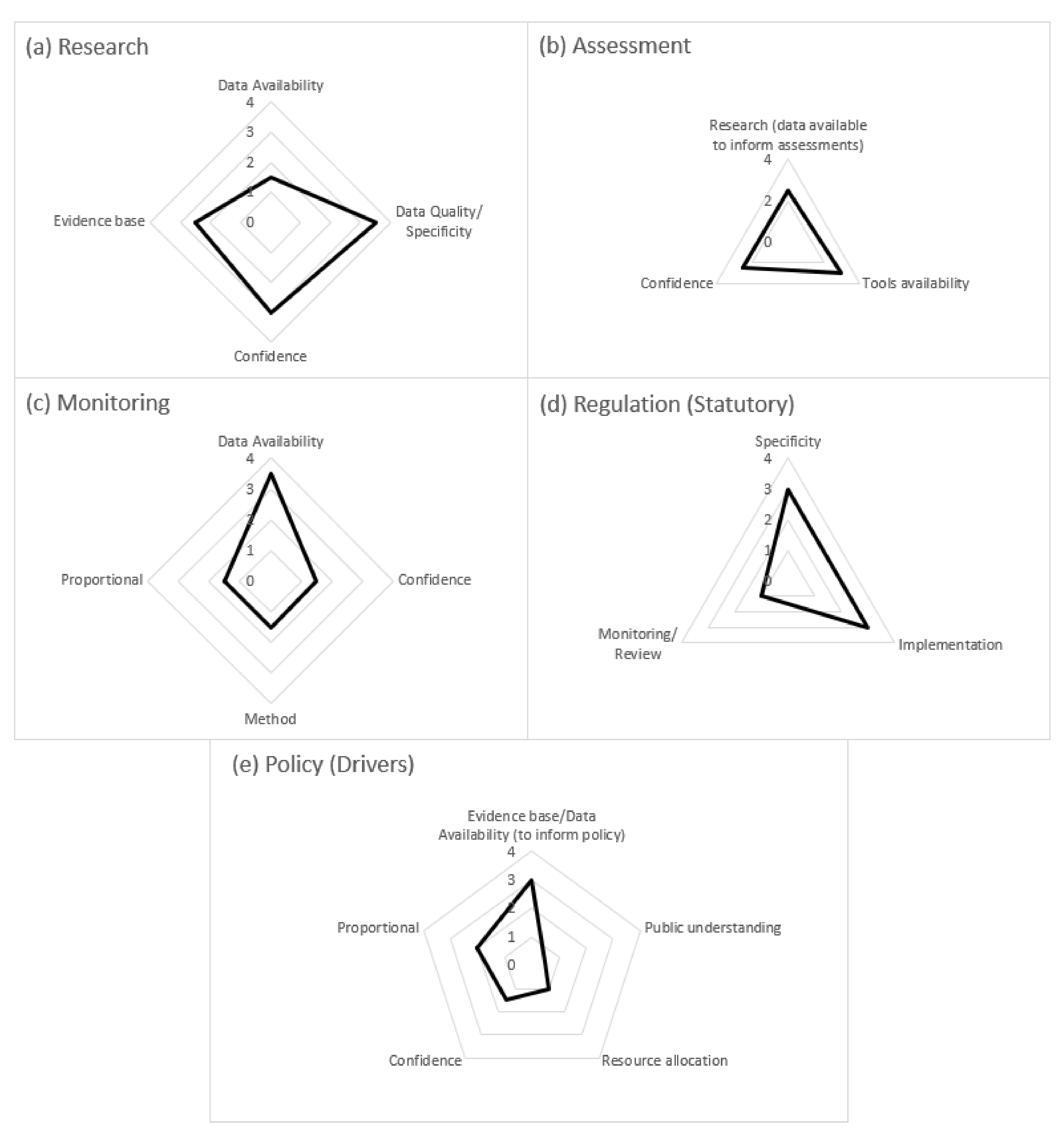

Appendix A. Criteria for Scoring Advice and Assessment Components

| 0 | No data available |

| 1 | Data are stored but not publicly available |

| 2 | Data are publicly available but for a fee |

| 3 | Data are publicly and freely available, but metadata are not available or not intuitive. |

| 4 | Data are publicly and freely available including all metadata |

| 0 | Data are not accurate, complete, reliable, relevant and are not up to date |

| 1 | Data are relevant, timely and complete but not accurate |

| 2 | Data are accurate but not timely nor complete |

| 3 | Data are accurate, relevant, and timely but not complete |

| 4 | Data are accurate, complete, reliable, relevant, and up to date |

| 0 | No data exist |

| 1 | Data are considered too old for the variable being assessed |

| 2 | Data are older than expected * for the receptor, a simple justification for newer data have been provided |

| 3 | Data are older than expected * for the receptor but a full justification for newer data have been provided |

| 4 | Data are timely for the variable being assessed |

| 0 | No data on which to base decisions. |

| 1 | The data are limited and not well supported by evidence. Experts do not agree. Outdated or inappropriate, not fit for purpose. |

| 2 | The data are limited and/or proxy information. There is a majority agreement between experts; however, evidence is inconsistent and there are differing views between experts. |

| 3 | The data used are timely *, some of the best available, robust and the outputs are well supported by evidence. Majority of experts agree. |

| 4 | The data used are timely *, the best available, robust and the outputs are supported by evidence. No disagreement between experts. Site specific, fit for purpose. |

| 0 | No regulations or policy in place |

| 1 | No regulations in place but there are policy ambitions around the receptor/impact/threat |

| 2 | Activity/theme is regulated under generic regulations |

| 3 | Activity/theme is regulated under a themed regulation |

| 4 | Regulations have been specifically enacted to address the receptor/impact/threat |

| 0 | No data available |

| 1 | Data are stored but not publicly available |

| 2 | Data are publicly available but for a fee |

| 3 | Data are publicly and freely available, but metadata are not available or not intuitive |

| 4 | Data are publicly and freely available including all metadata |

| 0 | No tools, frameworks, or guidance available to inform assessment |

| 1 | Generic tools, frameworks or guidance are available but not specific to the assessment |

| 2 | Specific tools, frameworks and/or guidance available to inform assessments but have not been tested |

| 3 | A specific tested single tool, framework and/or guidance is available to inform assessments |

| 4 | Specific tested tools, frameworks and/or guidance available to inform assessments |

| 0 | No scientific, rigorous, or justified method has been applied. |

| 1 | Method applied but no justification and not based on current best practice |

| 2 | Method applied which is no best practice, but justification provided |

| 3 | Method applied which is based on a previous best practice or on a low-cost option |

| 4 | Best practice has been applied. |

| 0 | No monitoring |

| 1 | Monitoring is required but all monitoring being carried out is under what is expected or over burdensome |

| 2 | Monitoring is required and some of the monitoring being carried out is under what is expected or over burdensome |

| 3 | Monitoring is required and mostly, the monitoring is proportional |

| 4 | Monitoring is proportional to the potential impacts predicted from the project |

| 0 | No aspect has yet been implemented |

| 1 | Policy/regulation has begun to be implemented, i.e., first steps such as organisation establishment |

| 2 | Phased implementation |

| 3 | Partial implementation |

| 4 | Full implementation has been achieved |

| 0 | No monitoring or review of the policy/regulation |

| 1 | Monitoring and/or review is carried out as required |

| 2 | Monitoring and/or review is carried out every ten years |

| 3 | Monitoring and/or review is carried out every five years |

| 4 | Monitoring and/or review is done on an annual basis |

| 0 | No public awareness or understanding |

| 1 | Public aware of issue but no understanding |

| 2 | Public aware of issue and with limited understanding |

| 3 | Public aware and understand the issue |

| 4 | Public are actively engaged in the issue |

| 0 | No resource allocated to implement |

| 1 | Under resourced to allow full implementation |

| 2 | Resource available to implement but with no flexibility to accommodate increases in work |

| 3 | Resource available to implement but with limited flexibility to accommodate increases in work |

| 4 | Resource available to implement including flexibility to accommodate increases in work |

Appendix B. Summary Tables for Case Studies

| Thematic Area | Element | Score | Rationale/Justification | Limitations/Gaps Examples | What This Means in Practice | Recommendations for Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research | Data availability | 2–2.5 | The results of the data analysis and methods used are available to the public. | Some data used in EIAs are not publicly available or may not be easy to access. | It may be difficult for interested parties outside of formal advisors or statutory bodies to have confidence in the types of data used to inform assessments. | Some data are not able to be shared publicly and we must respect data protection laws. Signposting interested parties to where public data are available will help with access issues more generally. |

| Research | Data quality/specificity | N/A | This is not considered here as a separate thematic topic area as it is captured under Evidence/knowledge base and Assessment N/A | |||

| Research | Confidence | 2–2.5 | Developers undertake site-specific surveys on which to base the EIA. | Certain topics/industries have higher uncertainty. Apply a receptor-based assessment. Empirical data used in modelling often have a higher level of confidence assigned to it than other forms of data especially where biological factors affect reliability, e.g., herring spawning grounds. | Site-specific data are vital to collect as each development is different and will have different impacts based on location. Applying a receptor-based assessment is useful as it is easier to obtain site-specific data focussed on specific receptors. However, it may miss more indirect impacts and larger scale/cumulative impacts. See below for uncertainty. | A requirement for a more mature science understanding where gaps remain including at the cumulative/larger geographical scale. |

| Research | Evidence/knowledge base | 2–2.5 | Some species (receptors) and impacts (from activity) are subject to more research: e.g., impact of wind turbines on birds [32], noise from piling on cetaceans [33] or shipping disturbance on a variety of species [34,35]. | Certain topics/industries have higher uncertainty: e.g., the effect of electromagnetic fields (EMF) from subsea cables on different life stages of sensitive fish and invertebrates [36,37] or the effects of specific chemicals like polybrominated flame retardants (PBFR) on marine life. Apply a receptor-based assessment. | Some topics have a wider knowledge base than others, meaning gaps in our knowledge remain, leading to higher uncertainty in the process of assessment of impacts. See above for receptor-based assessment. | A requirement for a more mature science understanding where gaps remain. |

| Assessment | Research (data available to inform assessments) | 3 | Developers undertake site-specific surveys on which to base the EIA. | Some developments, i.e., OWFs, can take years to be consented to and therefore data need to be updated. | Due to length of application process the information provided in an initial environmental report (such as scoping, characterisation or preliminary environmental information report) may require to be updated throughout the decision-making process to ensure a robust decision is made for example site-specific pre-construction surveys can be requested to be carried out where necessary. | Continued use of the Rochdale Envelope: an approach which allows the developer to assess a number of ‘worst case assessments’ for large projects where the EIA is being carried out either with years before consent and construction, or in cases where the technology is still being developed so construction methods are not defined [38]. |

| Assessment | Tools availability | 3 | Many tools available, e.g., guidelines by EC and IEMA; EIA checklist for scoping; the Marine Scotland Impact Assessment Tool (for wave and tidal device EIA) and the ODEMM approach to ecological risk assessment; Rochdale Envelope. | Not all tools are intuitive for non-specialists. | Tools require up-to-date data to be accurate (see above issue) and require specialists used to working with specific tools or approaches to undertake assessment. This can be costly to the developer. | Ensure guidelines are up-to-date and fit for purpose. Ensure tools are used appropriately and by properly trained experts. |

| Assessment | Timeliness | 3 | Developers undertake site-specific surveys on which to base the EIA. | Some developments, i.e., OWFs can take years to be consented to and therefore data need to be updated to inform tools. | See assessment research. | See assessment research. |

| Assessment | Confidence | 2.5 | Tools tend to specify the limitations of use to inform confidence assessments. Multiple tools available for diversity of marine users. | Some tools are used but do not get updated with newer data. | See assessment tool availability. | See assessment tool availability. |

| Assessment | Use | 3 | Tools are diverse for the diversity of marine users. Can be combined. | Expert judgement is often applied during assessment of significance. | It is often up to specialist advisors, such as the Cefas, to ensure that the information contained within an environmental report is sufficient to the best of their knowledge and to provide additional information to allow the decision maker to judge significance. This requires that the specialists are confident and competent in their assessment. | Ensure specialist advisors are appropriately trained and senior advisors are available for mentoring junior colleagues. Ensure decision makers are appropriately trained in interpreting results, advice and determining significance, and senior colleagues are available for mentoring junior colleagues. |

| Monitoring | Data availability | N/A | This is not considered here as a separate thematic topic area as data availability is linked to monitoring requirements and is site specific. Only know once you monitor what you will find. | |||

| Monitoring | Timeliness | N/A | This is not considered here as a separate thematic topic area as it is captured under confidence/timeliness as confidence is linked to timing of monitoring. | |||

| Monitoring | Confidence/timeliness | 3 | Hypothesis driven based on the results of the EIA. Timing of the monitoring is determined by the regulator based on scientific advice and results of EIS. | Force majeure, e.g., bad weather preventing surveys being undertaking can affect how results are analysed and interpreted. Difficult to assess results in terms of natural variation. For some receptors, need a long time series. | Monitoring is driven by EIA results, best practice, and expert advice. In theory monitoring should be ‘regular’ yet within guidelines for that sector/type if development. | See monitoring method and monitoring proportional. |

| Monitoring | Method | 3 | International standards based on best practice, e.g., International Finance Corporation. | Force majeure, e.g., bad weather preventing surveys being undertaking can affect how results are analysed and interpreted. Difficult to assess results in terms of natural variation. For some receptors, need a long time series. | To carry out monitoring, there are standards in place, based on best practice; however, monitoring cannot always be enforced due to other factors having to be considered by the regulator. In addition, if the applicant carries out the monitoring with major omissions (see force majeure) or that are not appropriate for the receptor, then the data will not inform the assessment as anticipated. | See monitoring proportional for force majeure issues. Consider, if not already present, producing specific basic monitoring requirements for specific types of development, recognising they will have site specific differences, e.g., standard monitoring conditions. |

| Monitoring | Proportional | 4 | Hypothesis driven based on the results of the EIA. | Force majeure, e.g., bad weather preventing surveys being undertaking can affect how results are analysed and interpreted. Difficult to assess results in terms of natural variation. For some receptors, need a long time series. | The regulator can apply licensing conditions for monitoring which will be hypothesis driven aimed at addressing a specific question for that specific project. Monitoring conditions are also often based on prior experience from equivalent past projects. For instance, there is no need to monitor the sediment type at offshore wind farms for contaminants because the risk in these areas is low. But there is generally a need to monitor seabed changes using bathymetry to measure areas of scour around the wind turbines which could have an effect on biodiversity, but also the structural integrity of the wind turbine. | Ensure monitoring conditions include flexibility for loss of survey data due to force majeure, e.g., regular repeatable monitoring over a long time series will allow for missing data gaps without losing too much of the time series. Additionally, if bad weather likely to have impacts on what monitoring (e.g., sediment composition), ensure this is taken into account in any post-weather monitoring occurring close to bad weather to account for natural variability. |

| Monitoring | Use/effectiveness | N/A | This is not considered here as a separate thematic topic area as use/effectiveness is directly linked to hypothesis formed by results of EIA. | |||

| Regulation | Specificity | 4 | The legislative drivers have been specifically implemented for EIA, with specific regulations for land and sea. | Annex II projects are open to interpretation. | Legislative drivers are specific and, whilst this is positive, it can mean new/novel forms of development get missed and/or do not fit within the regulations making it difficult to regulate such. | Ensure regulations are regularly reviewed and updated to capture missed/new forms of development/activity. Annex II projects may be open to interpretation but learning from best practice can help here. Need to train competent assessors. |

| Regulation | Implementation | 4 | Many EIA practitioners participate in international fora, such as ICES or OSPAR, to apply lessons learned domestically. The UK also has a comprehensive system in place to implement EIA regulations. | Implementation via the authoring, reviewing and determination of EIAs is subject largely to expert judgement. | Although heavily reliant on expert judgement and practices, given the wide input from international experts into learning and implementation practices, this should install a level of confidence in the process. | Ensure such learning is passed onto all the relevant regulatory bodies as not all attend international fora, and information is not always effectively communicated. |

| Regulation | Timeliness | 4 | Most of the primary legislation has been updated in the last five years, taking into account developments such as climate change. | New provisions need to be effectively implemented and tested. | See Regulation specificity as, although they have been updated, some new/novel forms of development may have been missed. | See Regulation specificity. |

| Regulation | Monitoring/Review | 1 | It is an obligation for any changes to be picked up and implemented by the relevant departments including advisory bodies | Frequency is not defined but at the discretion of the competent authorities and usually occur due to major legislative or policy landscape changes. | See above. | See Regulation specificity. Additionally, ensure such reviews and any updates these incur are passed onto all the relevant regulatory bodies and communicated within such bodies to relevant parties as part of updating training. |

| Policy | Evidence base/data availability (to inform policy) | 4 | There is a long history of EIA (including non-statutory impact assessments) within the UK. | Certain topics have fewer data or less timely data on which to base the policy. | The availability of evidence to inform policy has a general high confidence, primarily due to the long history of EIA in the UK; however, this could be tempered in light of lower confidence of Research overall, especially with regard to emerging activity and development, where we may not have a history of impacts to learn from directly. | A requirement for a more mature science understanding where gaps remain including at the cumulative/larger geographical scale. |

| Policy | Evidence/data quality | N/A | This is not considered here as a separate thematic topic area as it is captured under Research. | |||

| Policy | Stakeholder/Public understanding | 2 | Policies are subject to public consultations to allow public and stakeholders to understand the changes and feed into the process. | Level of understanding is often influenced by the impact on, and importance of the environment to, the individual stakeholder in question. | It needs to be noted that public understanding is often linked to what is ‘popular’ at the time, e.g., a topic that will have more publicly accessible information available and thus can be volatile but is considered with scientific and specialist stakeholder understanding. Overall low confidence in the stakeholder/public understanding as the team’s experience and understanding was that the level of understanding is often influenced by the impact on, and importance of the environment to, the individual stakeholder in question and thus is difficult to measure. | Ensure policy is balanced by being informed by scientific knowledge, evidence, understanding, best practice and stakeholder/public position. |

| Policy | Resource allocation | N/A | This is not considered here as a separate thematic topic area as this is dependent on the scale and type of development, e.g., which statutory bodies involved. N/A | |||

| Policy | Confidence | N/A | This is not considered here as a separate thematic topic area as it is captured under policy proportional and policy evidence base. N/A | |||

| Policy | Proportional | 3.5 | The proportionality of policy drivers is influenced by stakeholder/public understanding as well as evidence. | Level of understanding is often influenced by the impact on, and importance of the environment to, the individual stakeholder in question. | See Policy stakeholder/public understanding. | Ensure policy is balanced by being informed by scientific knowledge, evidence, understanding, best practice and stakeholder/public position. |

| Thematic Area | Element | Score | Rationale/Justification | Limitations/Gaps Examples | What This Means in Practice | Recommendations for Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research | Evidence availability | 3.5 | All data and evidence submitted are publicly available. | Some of the data are not freely or easily available. | Whilst data are freely available, for people new to the system, they may not be able to find the data easily and therefore request data through Environmental Information Requests, adding to time and monetary costs. | Having all data in an easily accessible format, e.g., an online portal that allows interrogation or interaction. Can be searched through multiple methods. However, such a system requires updating and maintaining. |

| Research | Evidence specificity | 3.5 | Best practice and international guidelines. | Some discrepancies, for instance between laboratories and experts. | Requires a level of trust between the regulator and the applicant and/or laboratory, which is true of most application systems. Follows best practice but with a level of pragmatism, so there are some variations, e.g., number of samples, based on evidence and expert knowledge of an area. | Either spot checking, i.e., MMO officer checking sample collection, laboratory methods and/or monitoring of the activities—however, this would incur a cost. |

| Research | Confidence | 3.5 | Good understanding of the impacts due to longevity of the sector. | Some variation amongst experts and signatory countries to international treaties/conventions. | There is a general understanding across the national experts, although the remit can often drive differences in advice. Will consider other approaches but must be led by national policy and precedents unless a good reason not to. | Research into the longevity of impacts from dredging and disposal for certain areas to validate advice would be beneficial; however, this would be research and not for the purposes of a licence condition. |

| Research | Evidence/knowledge base | 3 | Long history of activity including monitoring. Good understanding of the impacts. | Proxies are used where no thresholds exist, e.g., for chemical analysis results. | There is a general understanding across the national experts, although the remit can often drive differences in advice. There can often be differences in how experts view the results of contaminants where no threshold exists. | Ensuring there are thresholds for all contaminants where possible to reduce the reliance on expert judgement. |

| Assessment | Research (data available to inform assessments) | 4 | Good understanding of the impacts due to longevity of the sector | Some variation amongst experts and signatory countries to international treaties/conventions. | There is a general understanding across the national experts, although the remit can often drive differences in advice. Will consider other approaches but must be led by national policy and precedents unless a good reason not to. | Research into the longevity of impacts from dredging and disposal for certain areas to validate advice would be beneficial; however, this would be research and not for the purposes of a licence condition. |

| Assessment | Tools availability | 2 | e.g., Mapping software; OSPAR Guidelines; implementation of thresholds. | Requires expert judgement. Thresholds are not pass/fail, so open to subjectivity. | There is a general understanding across the national experts about the approaches to use. UK utilise mapping software to check where samples have historically been taken to inform future applications. There can often be differences in how experts view the results of contaminants where no threshold exists. | Ensuring there are thresholds for all contaminants where possible to reduce the reliance on expert judgement. |

| Assessment | Timeliness | 4 | OSPAR Guidelines set out how often sediment should be analysed. | Open to interpretation as guidelines, not mandatory. | There is a general understanding across the national experts, although the remit can often drive differences in advice. Will consider other approaches but must be led by national policy and precedents unless a good reason not to. | Ensuring there are thresholds for all contaminants where possible to reduce the reliance on expert judgement. Recommend guidelines stay as guidelines and not made mandatory as one size does not fit all. |

| Assessment | Confidence | 3 | Good understanding of the impacts due to longevity of the sector and access to international guidance. | Relies on expert judgement which can lead to differing conclusions. | There is a general understanding across the national experts, although the remit can often drive differences in advice. Will consider other approaches but must be led by national policy and precedents unless a good reason not to. | Research into the longevity of impacts from dredging and disposal for certain areas to validate advice would be beneficial; however, this would be research and not for the purposes of a licence condition. |

| Assessment | Use | 2.5 | Good understanding of the impacts due to longevity of the sector and access to international guidance. | Relies on expert judgement which can lead to differing conclusions. Tools and guidance not always use by developers. | There is a general understanding across the national experts, although the remit can often drive differences in advice. Will consider other approaches but must be led by national policy and precedents unless a good reason not to. | Research into the longevity of impacts from dredging and disposal for certain areas to validate advice would be beneficial; however, this would be research and not for the purposes of a licence condition. |

| Monitoring | Data availability | 2.5 | Results of the disposal sites are available publicly. | There is no method to search for disposal sites that have been monitored | Whilst data are freely available, for people new to the system, they may not be able to find the data easily and therefore request data through Environmental Information Requests, adding to time and monetary costs. | Having all data in an easily accessible format, e.g., an online portal that allows interrogation or interaction. Can be searched through multiple methods. However, such a system requires updating and maintaining. |

| Monitoring | Timeliness | 3 | Monitoring frequency will be a licence condition. The regulator-led monitoring is published the following financial year. | There is a lag between monitoring being undertaken and results/reports being made available. | Whilst data are freely available, for people new to the system, they may not be able to find the data easily and therefore request data through Environmental Information Requests, adding to time and monetary costs. | Having all data in an easily accessible format, e.g., an online portal that allows interrogation or interaction. Can be searched through multiple methods. However, such a system requires updating and maintaining. |

| Monitoring | Confidence/timeliness | 3.5 | There are international standards and best practices that are routinely applied, as well as standards for sample analysis, e.g., MMO. Monitoring and reporting frequency will be a licence condition. | There are differences between laboratories for chemical analysis which may result in different values being reported. | Requires a level of trust between the regulator and the applicant and/or laboratory, which is true of most application systems. Follows best practice but with a level of pragmatism so there are some variations, e.g., number of samples, based on evidence and expert knowledge of an area. | Either spot checking, i.e., MMO officer checking sample collection, laboratory methods and/or monitoring of the activities—however, this would incur a cost. |

| Monitoring | Method | 3 | There are international standards and best practices that are routinely applied, as well as standards for sample analysis, e.g., MMO. | There are differences between laboratories for chemical analysis which may result in different values being reported. | Requires a level of trust between the regulator and the applicant and/or laboratory, which is true of most application systems. Follows best practice but with a level of pragmatism so there are some variations, e.g., number of samples, based on evidence and expert knowledge of an area. | Either spot checking, i.e., MMO officer checking sample collection, laboratory methods and/or monitoring of the activities—however, this would incur a cost. |

| Monitoring | Proportional | 3.5 | Hypothesis driven based on the results of the assessment. | Force majeure, e.g., bad weather preventing surveys being undertaking can affect how results are analysed and interpreted. Difficult to assess results in terms of natural variation. For some receptors, need a long time series. | Monitoring to determine impacts in the context of background variation is difficult to ascertain yet decisions still need to be made as to whether the monitoring and/or activity should be allowed to continue (either as is, or with mitigation measures). Requiring additional time series data but being bound by the licence. | Ensure monitoring is continued for as long as required, i.e., ensure marine licence condition is hypothesis driven and not time bound in the first instance. |

| Monitoring | Use/effectiveness | This was not considered under this topic because this can be considered under the other monitoring elements. | ||||

| Regulation | Specificity | 2.5 | Specific provisions for dredge and disposal operations. Specific international guidance, e.g., OSPAR, 2014. | The regulations were not developed specifically for the management of dredge and disposal operations. | Often developers have to consult multiple legislative texts (MCAA, OSPAR, LCLP) as well as previous applications to ensure following mandatory and recommended texts, as well as applying consistently and any variation is (still legal) based on sound evidence. | None recommended—the regulations are updated to reflect changes in methods and science. International treaties are clear. Recommend guidelines stay as guidelines and not made mandatory as one size does not fit all. |

| Regulation | Implementation | 4 | The Marine and Coastal Access Act has now been implemented for over ten years and based on previous regulations and therefore well-established across a multitude of activities and developments. | No major weaknesses identified. | For standard dredge and disposals, MCAA is now well known amongst its regular users. For less routine, e.g., accelerated dredges, the exemptions and guidance are available online. | No major weaknesses identified. |

| Regulation | Timeliness | 4 | The Marine and Coastal Access Act has recently been updated 2019 to refine the activities exempt from requiring a marine licence. | New provisions need to be effectively implemented and tested. | For standard dredge and disposals, MCAA is now well known amongst its regular users. For less routine, e.g., accelerated dredges, the exemptions and guidance are available online. | No major weaknesses identified. New provisions need to be effectively implemented and tested. |

| Regulation | Monitoring/Review | 1 | It is an obligation for any changes to be picked up and implemented by the relevant departments including advisory bodies. | Frequency is not defined but at the discretion of the competent authorities and usually occur due to major legislative or policy landscape changes. | Due to the time and cost of updating regulations, this tends to be carried out when there is a major shift in understanding, e.g., the implementation of the exemptions and amendments for agitation dredging. Smaller discrepancies may be put ‘on hold’. | None recommended—the regulations are updated to reflect changes in methods and science. International treaties are clear. Recommend guidelines stay as guidelines and not made mandatory as one size does not fit all. New provisions need to be effectively implemented and tested. |

| Policy | Evidence base/data availability (to inform policy) | 4 | Evidence collection and assessment follow the international guidance, and all data are publicly available. | Regulators should consider advancements in scientific field, but it is recognised that amending criteria for methods or thresholds could have socio-economic implications which should be balanced. | Advancements can take time to come online as impact assessments must be undertaken, as well as challenging the legality of changes (does it change our position legally) and the robustness of evidence (does the change make a marked step forward in terms of evidence confidence?). | No major weaknesses identified. Where gaps are identified and considered a priority, funding can be made available to investigate how to implement. |

| Policy | Evidence/data quality | This is the same for evidence base for this sector. | ||||

| Policy | Stakeholder/Public understanding | 2 | Policies are subject to public consultations to allow public and stakeholders to understand the changes and feed into the process. | Limited understanding of the specific needs, assessments, requirements or how these are driven by the policies and social science brings this additional information on human behaviour to the fore. | There are no specific policies for dredge and disposal operations in terms of navigation (some are embedded in terms of flood management). Approach is driven by national legislation and international treaties, as well as guidance. Public involvement tends to be for issues such as flooding or high-profile cases such as Hinkley. | No major weaknesses identified. Policy makers and regulators may want to consider having public documents which explain the process for answering EIRs as individual responses can be time consuming. |

| Policy | Resource allocation | 2.5 | There is currently sufficient resource within the organisations to continue the status quo. | Recognised lag between high case work and being able to employ further resource leading to a temporary period of constraint working. | Generally, all work is completed to set timelines, regardless of resource availability. Recognised that new colleagues in all organisations require some level of support. | No major weaknesses identified. |

| Policy | Confidence | This is the same for evidence base for this sector. | ||||

| Policy | Proportional | 4 | Regulators often utilise the expertise of their (statutory and non-statutory) scientific advisors, such as the Cefas, utilising corporate knowledge to ensure proportionality. | Relies on either long-standing members of an organisation or effective succession planning and filing to ensure consistency. | The employment of document storage systems, mapping tools and databases to allow colleagues to ‘take over’ when needed and take into consideration previous advice. | No major weaknesses identified. Would benefit from having all data in an easily accessible format, e.g., an online portal that allows interrogation or interaction. Can be searched through multiple methods. However, such a system requires updating and maintaining. |

| Thematic Area | Element | Score | Rationale/Justification | Limitations/Gaps Examples | What This Means in Practice | Recommendations for Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research | Evidence availability | 2.5 | There are several studies that have been undertaken internationally. | Data underpinning these studies are often not released as they are being analysed for research purposes. | That some data are made available for other studies, although even freely available data are not available for some time and may not be aware the data are available unless known, can limit studies. | All research data should be stored on public databases to aid access. Database access should be user developed rather than holder developed to avoid unnecessarily complex download process. |

| Research | Evidence specificity | 2 | Research undertaken to answer specific questions or gaps. | The quality is variable and misses key elements required for designation. | Data are available, but often at considerable cost in terms of time or fees which means others cannot easily use to inform their own assessments. | All research data should be stored on public databases to aid access. Database access should be user developed rather than holder developed to avoid unnecessarily complex download process. |

| Research | Confidence | 2.5 | Some programmes are specific and undertaken using international methods. | Other studies rely on stakeholder input. | The reliance on stakeholder input allows for additional information which may not otherwise be collected and the proposals generally more accepted if the public feel they contributed and own the decision, but stakeholder data often has lower confidence than empirical data. | Research into how current data can be pulled together, but also going forward, standard data requirements set by regulators to aid in comparability and carrying out ecosystem-level assessments. |

| Research | Evidence/knowledge base | 2.5 | Extensive studies have been undertaken internationally. | Fewer studies have been carried out on UK-specific MPAs. | Confidence in the individual studies is good. However, extrapolation to UK ecosystem-level effects is very limited. | Research into how current data can be pulled together, but also going forward, standard data requirements set by regulators to aid in comparability and carrying out ecosystem-level assessments. |

| Assessment | Research (data available to inform assessments) | These are not considered as separate thematic topic areas as these are covered in Research and Monitoring. | ||||

| Assessment | Tools availability | |||||

| Assessment | Timeliness | |||||

| Assessment | Confidence | |||||

| Assessment | Use | |||||

| Monitoring | Data availability | 1.5 | There are a number of studies that have been undertaken internationally. | Data underpinning these studies are often not released as they are being analysed for research purposes | Data are available, but often at considerable cost in terms of time or fees which means others cannot easily use to inform their own assessments. | All research data should be stored on public databases to aid access. Database access should be user developed rather than holder developed to avoid unnecessarily complex download process. |

| Monitoring | Timeliness | This is not considered as a separate thematic topic area as this is covered under (Monitoring) confidence/timeliness. | ||||

| Monitoring | Confidence/timeliness | 2 | Some programmes are specific and undertaken using international methods. | Other studies rely on stakeholder input which can have lower confidence or data are limited. | Confidence in the individual studies is good. However, extrapolation to ecosystem-level effects is very limited. | Research into how current data can be pulled together, but also going forward, standard data requirements set by regulators to aid in comparability and carrying out ecosystem-level assessments. |

| Monitoring | Method | 2 | Defined processes for designating MPAs. | Due to limitations of some data, a precautionary approach can be taken. Some gaps in knowledge. | Some MPAs require additional monitoring following designation to fill some of the gaps and inform the assessment for meeting favourable condition. | There is little improvement that can be done given statutory timelines for designating national MPAs. |

| Monitoring | Proportional | 2 | Management measures assessed at the designation stage. Over 120 byelaws have been introduced. | Some uncertainty exists which can lead to precautionary approaches being applied. | Some MPAs require additional monitoring following designation to fill some of the gaps and inform the assessment for meeting favourable condition. | There is little improvement that can be done given statutory timelines for designating national MPAs. |

| Monitoring | Use/effectiveness | 1.5 | Over 120 byelaws have been introduced. Monitoring programme in place. | No assessment has been undertaken on the effectiveness of management measures. Monitoring programme in early stages. | Due to the early stages of the management measures, there is little information regarding their effectiveness in situ. Changing conditions may also require a change measure which may not easily be identified or implemented. | There is little improvement at this stage given the early stages of the monitoring programme, but monitoring should be hypothesis driven and linked to conservation objectives/management measures. |

| Regulation | Specificity | 4 | National regulations are not specifically for the designation of MPAs but provide a strong statutory requirement. International directives specific for MPAS. | The national regulations were not developed specifically for the designation of MPAs. | Often have to consult multiple legislative texts (MCAA, TCPA, Directives) to ensure following mandatory and recommended texts, as well as applying consistently and any variation is (still legal) based on sound evidence. | None recommended—the regulations are updated to reflect changes in methods and science. International treaties are clear. Recommend guidelines stay as guidelines and not made mandatory as one size does not fit all. |

| Regulation | Implementation | 4 | The EU Directives have resulted in 933 MPAs, and The Town and Country Planning Act has been implemented since 1990 and has resulted in 4126 SSSIs (including terrestrial). Under the MCAA, the UK in 2019 fully implemented the MCZ network and has worked to create an ecologically coherent network which is deemed sufficiently complete. | Non-specific to the regulations. | MPAs under all legislation has been implemented, with some having been monitored and assessed against baselines. | None recommended. The regulations have been successfully implemented. |

| Regulation | Timeliness | 4 | There is an international ambition to increase marine protected areas and the combination of the regulations set out how to meet requirement. | Some of regulations are over 30 years old. | Whilst some regulations are old, they have been updated and guidelines updated to reflect evolving knowledge. | None recommended—the regulations are updated to reflect changes in methods and science. International treaties are clear. Recommend guidelines stay as guidelines and not made mandatory as one size does not fit all. |

| Regulation | Monitoring/Review | 2.5 | For MCZs, there is a statutory requirement to review every six years. For European sites, there is a requirement to monitor. | The large number of sites and features designated require large resources to monitor effectively. | Due to the early stages of the management measures, there is little information regarding their effectiveness in situ. Changing conditions may also require a change measure which may not easily be identified or implemented. | There is little improvement at this stage given the early stages of the monitoring programme, but monitoring should be hypothesis driven and linked to conservation objectives/management measures. |

| Policy | Evidence base/data availability (to inform policy) | 1 | The data behind these designations are available. | Data need to be requested for use. | That some data are made available for other studies, although even freely available data are not available for some time and may not be aware the data are available unless known, can limit studies. | All research data should be stored on public databases to aid access. Database access should be user developed rather than holder developed to avoid unnecessarily complex download process. |

| Policy | Evidence/data quality | 2.5 | MPAs were designated based on best available evidence, with additional surveys being deployed to update data or increase confidence. | Some sites and features that require data of better quality or spatial representation, and/or knowledge and some data are more recent than others. | Data are available, but often at considerable cost in terms of time or fees which means others cannot easily use to inform their own assessments. | All research data should be stored on public databases to aid access. Database access should be user developed rather than holder developed to avoid unnecessarily complex download process. |

| Policy | Stakeholder/Public understanding | 2.5 | There has been increased publicity in the marine environment through political agendas but also due to advocates such as David Attenborough. MCZs were originally designed to be ‘bottom up’ with stakeholders. | There are different levels of knowledge, understanding and engagement. | Some of the public are for or against, and much depends on livelihood, i.e., fishermen do not want to be affected by management measures in the MPAs. Some of this is due to the early stages of national MPAs and management measures. | Education of the public on marine management as a whole as there is no one approach to management, nor one solution. |

| Policy | Resource allocation | This is not considered due to the wide-ranging input from different agencies into the designation and management of MPAs. | ||||

| Policy | Confidence | This is not considered as a separate thematic topic area as this is covered under (Policy) for evidence base and evidence quality, as well as research and monitoring. | ||||

| Policy | Proportional | 3.5 | The policies around the designation of MCZs were based on a balanced approach of available science/evidence/data, uncertainty, and the economic impact. | Some uncertainties regarding management measures leading to precautionary approaches being applied. | Some MPAs require additional monitoring following designation to fill some of the gaps and inform the assessment for meeting favourable condition. | There is little improvement that can be done given statutory timelines for designating national MPAs. |

| Thematic Area | Element | Score | Rationale/Justification | Limitations/Gaps Examples | What This Means in Practice | Recommendations for Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research | Evidence availability | 1.5 | Academic and government research data are well publicised and published. Databases such as the Tethys Environmental Effects of Wind and Marine Renewable Energy have helped reduce the effort required to find information. Coordinated programmes such as Collaborative Offshore Windfarm Research Into the Environment (COWRIE), ORJIP and <Belgium OWF research, WREN/Annex4>. There are a number of studies that have been undertaken internationally. | Many datasets require personal requests for the data rather than being directly downloadable. Developer data such as details of devices, installation methods, timings are often not available. Industry data may also be behind subscription or membership services (e.g., 4COffshore or RenewableUK). These services are often prohibitively expensive to academic and government researchers. | Data are available, but often at considerable cost in terms of time or fees which means others cannot easily use to inform their own assessments. | All research data should be stored on public databases to aid access. Database access should be user developed rather than holder developed to avoid unnecessarily complex download process. |

| Research | Evidence specificity/Quality | 3.5 | Outputs that are made available appear to be of good quality. | There are constraints around being able to re-use data. | Data are available, but often at considerable cost in terms of time or fees which means others cannot easily use to inform their own assessments. | All research data should be stored on public databases to aid access. Database access should be user developed rather than holder developed to avoid unnecessarily complex download process. |

| Research | Confidence | 3 | Data appear to be of good quality and are generally specific to the question/hypothesis being investigated. | Most studies are too small in scale to be applied beyond the scale of the study. Very few studies focus on effects at the ecosystem level. | Confidence in the individual studies is good. However, extrapolation to ecosystem-level effects is very limited. | Research into how current data can be pulled together, but also going forward, standard data requirements set by regulators to aid in comparability and carrying out ecosystem-level assessments. |

| Research | Evidence/knowledge base | 2.5 | There are certain areas of research which have received a of research and a sound evidence base. These include seabirds, underwater noise, and marine mammals. | Areas such as effects of EMF, effects on benthos and effects on fisheries have received relatively little research. | Research in many areas is being driving by licensing issues, often receptor groups such as seabirds and marine mammals. | Research should be ecosystem-led and coordinated to avoid duplication of effort. Programmes of sufficient size are required to answer |

| Assessment | Research (data available to inform assessments) | 2.5 | Data appear to be of good quality and are generally specific to the question/hypothesis being investigated. | There are constraints around being able to re-use data. | Data are available, but often at considerable cost in terms of time or fees which means others cannot easily use to inform their own assessments. | All research data should be stored on public databases to aid access. Database access should be user developed rather than holder developed to avoid unnecessarily complex download process. |

| Assessment | Tools availability | 3 | There are established guidelines for carrying out EIAs across industries. | Identifying which species and impacts to be assessed is industry/site specific and requires expert judgement. | Whilst there are guidelines in place, these are generic to cover and cannot cover all species, impacts or environmental conditions and therefore assessments are often subject to subjectivity in the assessor and reviewer. | Whilst there will always be a degree of subjectivity, Regulator-led standards could reduce the subjectivity. |

| Assessment | Timeliness | N/A | This is not considered as a separate thematic topic area as it is captured under confidence/timeliness as confidence linked to timing of monitoring. | |||

| Assessment | Confidence | 2.5 | Data appear to be of good quality and are generally specific to the question/hypothesis being investigated. | There is no formal process of cross checking or quality assuring data produced by developers. | Reviewers cannot review the quality assurances processes nor all the steps to assure themselves in the assessment and therefore decisions are based on whether the approaches and conclusions appear reasonable. | Regulator-led data standards would reduce the uncertainty in confidence levels. Demonstrating the data collection, cleansing and analysis steps in line with regulator-led standards would increase confidence in decisions. |

| Assessment | Use | N/A | This is not considered as a separate thematic topic area as it is captured under Research which takes into account the usability of the data. | |||

| Monitoring | Data availability | 3.5 | Data produced from baseline surveys and monitoring can be made available. | Data are not always easily available and, in some circumstances, relies on knowledge on the data existing. | Data are available, but often at considerable cost in terms of time or fees which means others cannot easily use to inform their own assessments. | All research data should be stored on public databases to aid access. Database access should be user developed rather than holder developed to avoid unnecessarily complex download process. |

| Monitoring | Timeliness | N/A | This is not considered as a separate thematic topic area as it is captured under confidence/timeliness as confidence linked to timing of monitoring. | |||

| Monitoring | Confidence/timeliness | 1.5 | Monitoring can be appropriate to address the issues related to the EIA. | Broader uses of such data can be limited. | Confidence in the individual studies is good. However, extrapolation to ecosystem-level effects is very limited. | Research into how current data can be pulled together, but also going forward, standard data requirements set by regulators to aid in comparability and carrying out ecosystem-level assessments. |

| Monitoring | Method | 1.5 | There are international standards and best practice for undertaking surveys and analysis. | Some decisions are driven by cost. | Some monitoring surveys are not carrying out the level of survey required to detect change because to do so would be costly; therefore, often a ‘compromise’ is reached to inform monitoring assessments. | Ensuring all monitoring is hypothesis driven and limitations noted at the start of the process, i.e., at survey design. Ensuring the hypothesis is linked to the licensing condition. |

| Monitoring | Proportional | 1.5 | Monitoring is hypothesis driven to reduce uncertainty. | Due to new technology, there is greater uncertainty regarding impacts, and therefore requires more monitoring at the inception. | Due to new technology, there is greater uncertainty regarding impacts, and therefore requires more monitoring at the inception. | Ensuring that monitoring is proportional, i.e., new technology, or larger projects, where there is high uncertainty, may require more monitoring to understand the impacts/effects. |

| Monitoring | Use/effectiveness | This is not considered as a separate thematic topic area as use/effectiveness is directly linked to hypothesis formed by results of the associated EIA. There is no sector-wide monitoring. | ||||

| Regulation | Specificity | 3 | Specific criteria related to offshore renewables as to which regulations projects fall under. | The national regulations were not developed specifically for offshore renewables. | Often have to consult multiple legislative texts (MCAA, Marine EIA Work Regs, Planning Act) as well as previous applications to ensure following mandatory and recommended texts, as well as applying consistently and any variation is (still legal) based on sound evidence. | None recommended—the regulations are updated to reflect changes in methods and science. International treaties are clear. Recommend guidelines stay as guidelines and not made mandatory as one size does not fit all. |

| Regulation | Implementation | 3 | Regulations have been implemented for offshore renewables including offshore wind and demonstration projects for tidal. | New technologies are being developed which have yet to be tested under the regulations. | With larger developments (Round 4) moving into less understood waters, and new technologies advancing, need to ensure the assessments and monitoring are in line with current legislation but as these evolve, weaknesses may be identified. | No major weaknesses identified at present, more highlighting the need to be aware of advancements which have yet to be legally tested in terms of assessment. |

| Regulation | Timeliness | This is not considered as a separate thematic topic area as it is captured under Implementation. | ||||

| Regulation | Monitoring/Review | 1 | It is an obligation for any changes to be picked up and implemented by the relevant departments including advisory bodies but no statutory/regular review in place. | Frequency is not defined but at the discretion of the competent authorities and usually occur due to major legislative or policy landscape changes. | Due to the time and cost of updating regulations, this tends to be carried out when there is a major shift in understanding. Smaller discrepancies may be put ‘on hold’. | None recommended—the regulations are updated to reflect changes in methods and science. International treaties are clear. Recommend guidelines stay as guidelines and not made mandatory as one size does not fit all. New provisions need to be effectively implemented and tested. |

| Policy | Evidence base/data availability (to inform policy) | 3 | The UK policy has been drawn together based on a number of national and international drivers. | There are some cases where these are not interpreted appropriately and are designed for legal protection as opposed to sustainable development. | Advancements can take time to come online as impact assessments must be undertaken, as well as challenging the legality of changes (does it change our position legally) and the robustness of evidence (does the change make a marked step forward in terms of evidence confidence?). | Due to new technologies (e.g., floating wind, lagoons), policies may require updating for the ‘UK view’ |

| Policy | Evidence/data quality | This is not considered as a separate thematic topic area as it is captured under Research. | ||||

| Policy | Stakeholder/public understanding | 0.5 | There are policies regarding decarbonisation and renewable energy sources. | There is little public understanding regarding the complexities that are required to be assessed and balanced by the regulators and decision makers. | The public tend to be in favour or against renewable energy, due to the NIMBY attitude [39], but they may not be aware of all of the UKs international obligations to meet targets such as % of energy from renewable sources. | Education of the public on marine management, as a whole, as there is no one approach to management, nor one solution. |

| Policy | Resource allocation | 1 | UK government has recently created an Offshore Wind team to ensure this joined up approach is established and maintained to deliver the decarbonisation targets. | There is recognition that there are steps to improve this to meet the ambitions. | This team looks across the board at the potential for meeting UK targets but also conflicts with other marine users such as MPAs. This is a relatively new team hence the low score. | To ensure cross-government collaboration and communication regarding offshore renewables to ensure no duplication of effort (wasting resource) but also highlight and prioritise gaps, to make best use of resources. |

| Policy | Confidence | 1.5 | UK policy has been drawn together based on a number of national and international drivers | Development is based on aspirational targets set at international fora, but this may not be achievable either due to technological status, regulatory burden, or uncertainty in the science. | Development is based on aspirational targets set at international fora, but this may not be achievable either due to technological status, regulatory burden, or uncertainty in the science. | To undertake an analysis of whether the UK could achieve the aspirational targets and, if not, why not to focus priorities, etc. |

| Policy | Proportional | 2 | The policy regarding offshore renewables has been developed and is increasing, due to a combination of factors: lower availability of oil and gas, which is increasing prices; increasing need for energy efficiency and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to lower the rate and impacts of climate change. | Lack of current resource and strategic overview, low public awareness of the intricacies behind the policies and decision making. It is acknowledged that there is a lag between the policies being implemented and the targets being achieved | The public are not aware of the intricacies of ensuring the UK meet our targets and therefore can object to developments without the bigger picture. There can be conflicts between targets (MPAs and offshore renewables). | Educate the public. Allow the Offshore Wind Enabling Team to look across the broader marine environment to consider synergies and conflicts. To undertake an analysis of whether the UK could achieve the aspirational targets and, if not, why not to focus priorities, etc. |

References

- Cabral, H.; Marques, J.C.; Guilhermino, L.; de Jonge, V.; Elliott, M. Coastal systems under change: Tuning assessment and management tools. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 167, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, J.; Birchenough, A. Dredge Material Disposal Sites and Marine Protected Areas around the English Coast: Desk Review—Part 2; Final Report, Report for Natural England, Cefas Contract Report C6230; Cefas: Lowestoft, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Knights, A.M.; Koss, R.S.; Robinson, L.A. Identifying common pressure pathways from a complex network of human activities to support ecosystem-based management. Ecol. Appl. 2013, 23, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodsir, F.; Bloomfield, H.J.; Judd, A.D.; Kral, F.; Robinson, L.A.; Knights, A.M. A spatially resolved pressure-based approach to evaluate combined effects of human activities and management in marine ecosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci 2015, 72, 2245–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Austen, M.C.; Crowe, T.P.; Elliott, M.; Paterson, D.M.; Peck, M.A.; Piraino, S. VECTORS of change in the marine environment: Ecosystem and economic impacts and management implications. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 201, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenberg, A.A.; McLeod, K.L. Implementing ecosystem-based approaches to management for the conservation of ecosystem services. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005, 300, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.M.; Hazen, E.L.; Lewison, R.L.; Dunn, D.C.; Bailey, H.; Bograd, S.J.; Briscoe, D.K.; Fossette, S.; Hobday, A.J.; Bennett, M.; et al. Dynamic ocean management: Defining and conceptualizing real-time management of the ocean. Mar. Policy 2015, 58, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.; Borja, A.; McQuatters-Gollop, A.; Mazik, K.; Birchenough, S.N.R.; Andersen, J.H.; Painting, S.; Peck, M. Force majeure: Will climate change affect our ability to attain good environmental status for marine biodiversity? Mar. Pollut. 2015, 95, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Galler, C.; Albert, C.; von Haaren, C. From regional environmental planning to implementation: Paths and challenges of integrating ecosystem services. Ecosystem 2016, 18, 18–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, A.; Elliott, M. The use of environmental integrative indicators to assess seabed disturbance in estuaries and coasts: Application to the Humber Estuary, UK. Mar. Pollut. 2006, 53, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarff, G.; Fitzsimmons, C.; Gray, T. The new mode of marine planning in the UK: Aspirations and challenges. Mar. Policy 2015, 51, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markus, T. Challenges and foundations of sustainable ocean governance. In Handbook on Marine Environment Protection; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 545–562. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, K.S.; Hobday, A.J.; Thompson, P.A.; Lenton, A.; Stephenson, R.L.; Mapstone, B.D.; Dutra, L.X.; Bessey, C.; Boschetti, F.; Cvitanovic, C.; et al. Proactive, reactive, and inactive pathways for scientists in a changing world. Earths Future 2019, 7, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E.; Ballinger, R.C. Welsh legislation in a new era: A stakeholder perspective for coastal management. Mar. Policy 2018, 97, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyam, S.S.; Shridhar, N.; Fernandez, R. Climate change and need for proactive policy initiatives in Indian marine fisheries sector. Clim. Change 2017, 3, 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- HM Government. UK Marine Policy Statement; The Stationary Office: London, UK, 2011.

- Carpenter, S.R.; Mooney, H.A.; Agard, J.; Capistrano, D.; DeFries, R.S.; Díaz, S.; Dietz, T.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Oteng-Yeboah, A.; Pereira, H.M.; et al. Science for managing ecosystem services: Beyond the millennium ecosystem assessment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gill, A.B.; Birchenough, S.N.; Jones, A.R.; Judd, A.; Jude, S.; Payo-Payo, A.; Wilson, B. Environmental implications of offshore energy. In Offshore Energy and Marine Spatial Planning; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 132–168. [Google Scholar]

- Claudet, J.; Bopp, L.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Devillers, R.; Escobar-Briones, E.; Haugan, P.; Heymans, J.J.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Matz-Lück, N.; Miloslavich, P.; et al. A Roadmap for Using the UN Decade of ocean science for sustainable development in support of science, policy and action. ONE Earth 2020, 2, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willsteed, E.A.; Jude, S.; Gill, A.B.; Birchenough, S.N. Obligations and aspirations: A critical evaluation of offshore wind farm cumulative impact assessments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2332–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, S.; Langman, R.; Lowe, S.; Weiss, L.; Walker, R.; Mazik, K. The Applicability of Environmental Indicators of Change to the Management of marine Aggregate Extraction; CEFAS: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bolam, S.G.; Rees, H.L.; Somerfield, P.; Smith, R.; Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M.; Atkins, M.; Garnacho, E. Ecological consequences of dredged material disposal in the marine environment: A holistic assessment of activities around England and Wales coastline. Mar. Pollut. 2006, 52, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JNCC. UK Marine Protected Area Network Statistics. 2020. Available online: https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-marine-protected-area-network-statistics/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- JNCC; Natural England. Levels of Evidence Required for the Identification, Designation, and Management of Marine Conservation Zones; Natural England: York, UK; The Joint Nature Conservation Committee: Peterborough, UK, 2011; p. 11. Available online: http://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/c812bf90-1e37-4623-ab6a-e97f471a2492/MCZ-LevelsOfEvidence-2011-JNCC-NE.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- JNCC; Natural England. MCZ Levels of Evidence. Advice on When Data Supports a Feature/Site for Designation from a Scientific, Evidence-Based Perspective. 2016; 25p. Available online: http://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/c812bf90-1e37-4623-ab6a-e97f471a2492/MCZ-levels-of-evidence-Addendum-2016.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Walker, P.; Mason, R.; Carrington, D. Theresa May commits to net zero UK carbon emissions by 2050. Guardian 2019, 11, 19. [Google Scholar]

- The Crown Estate. Offshore Wind Operational Report. January–December 2018; The Crown Estate: London, UK, 2020; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- James, R.; Martins, E. Future Potential for Offshore Wind in Wales. The Carbon Trust Prepared for the Welsh Government. December 2018. Available online: https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-07/future-potential-for-offshore-wind.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- MMO. Review of Post-Consent Offshore Wind Farm Monitoring Data Associated with Licence Conditions. A Report Produced for the Marine Management Organisation; Marine Management Organization: Newcastle, UK, 2014; 194p, ISBN 978-1-909452-24-4. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/317787/1031.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Birchenough, S.N.; Degraer, S. Science in support of ecologically sound decommissioning strategies for offshore man-made structures: Taking stock of current knowledge and considering future challenges. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2020, 77, 1075–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodsir, F.; Lonsdale, J.A.; Mitchell, P.J.; Suehring, R.; Farcas, A.; Whomersley, P.; Brant, J.L.; Clarke, C.; Kirby, M.F.; Skelhorn, M.; et al. A standardized approach to the environmental risk assessment of potentially polluting wrecks. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 142, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, H.; Heinänen, S.; Norman, T.; Ward, R.; Méndez, S. ORJIP Bird Avoidance Behaviour and Collision Impact Monitoring at Offshore Wind Farms; The Carbon Trust: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, I.M.; Pirotta, E.; Merchant, N.D.; Farcas, A.; Barton, T.R.; Cheney, B.; Hastie, G.D.; Thompson, P.M. Responses of bottlenose dolphins and harbor porpoises to impact and vibration piling noise during harbor construction. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blair, H.B.; Merchant, N.D.; Friedlaender, A.S.; Wiley, D.N.; Parks, S.E. Evidence for ship noise impacts on humpback whale foraging behaviour. Biol. Lett. 2016, 12, 20160005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.L.; Hastie, G.D.; Smout, S.; Onoufriou, J.; Merchant, N.D.; Brookes, K.L.; Thompson, D. Seals and shipping: Quantifying population risk and individual exposure to vessel noise. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1930–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, Z.L.; Gill, A.B.; Sigray, P.; He, H.; King, J.W. Anthropogenic electromagnetic fields (EMF) influence the behaviour of bottom-dwelling marine species. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dannheim, J.; Bergström, L.; Birchenough, S.N.; Brzana, R.; Boon, A.R.; Coolen, J.W.; Dauvin, J.C.; De Mesel, I.; Derweduwen, J.; Gill, A.B.; et al. Benthic effects of offshore renewables: Identification of knowledge gaps and urgently needed research. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2019, 77, 1092–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, J.; Weston, K.; Blake, S.; Edwards, R.; Elliott, M. The amended European environmental impact assessment directive: UK marine experience and recommendations. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2017, 148, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. Wind power and the NIMBY-myth: Institutional capacity and the limited significance of public support. Renew. Energy 2000, 21, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Foci | Areas of Potential Conflict | Timeliness |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental impact assessment legislation | Marine management approach | The EIA legislation is established but is still evolving with new knowledge |

| Dredge and disposal operations | Human activities from dredge and disposal | Dredge and disposal are considered an historic activity as it has been ongoing for decades |

| Marine protected areas process | Legislation | Marine protected areas are established for their effectiveness is yet to be quantified |

| Offshore renewable energy | Offshore infrastructure (renewables) | Offshore renewable energy is a relatively new sector where the technology is still advancing |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lonsdale, J.-A.; Gill, A.B.; Alliji, K.; Birchenough, S.N.R.; Blake, S.; Buckley, H.; Clarke, C.; Clarke, S.; Edmonds, N.; Fonseca, L.; et al. It Is a Balancing Act: The Interface of Scientific Evidence and Policy in Support of Effective Marine Environmental Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031650

Lonsdale J-A, Gill AB, Alliji K, Birchenough SNR, Blake S, Buckley H, Clarke C, Clarke S, Edmonds N, Fonseca L, et al. It Is a Balancing Act: The Interface of Scientific Evidence and Policy in Support of Effective Marine Environmental Management. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031650

Chicago/Turabian StyleLonsdale, Jemma-Anne, Andrew B. Gill, Khatija Alliji, Silvana N. R. Birchenough, Sylvia Blake, Holly Buckley, Charlotte Clarke, Stacey Clarke, Nathan Edmonds, Leila Fonseca, and et al. 2022. "It Is a Balancing Act: The Interface of Scientific Evidence and Policy in Support of Effective Marine Environmental Management" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031650

APA StyleLonsdale, J.-A., Gill, A. B., Alliji, K., Birchenough, S. N. R., Blake, S., Buckley, H., Clarke, C., Clarke, S., Edmonds, N., Fonseca, L., Goodsir, F., Griffith, A., Judd, A., Mulholland, R., Perry, J., Randall, K., & Wood, D. (2022). It Is a Balancing Act: The Interface of Scientific Evidence and Policy in Support of Effective Marine Environmental Management. Sustainability, 14(3), 1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031650