Regional Cooperation in Waste Management: Examining Australia’s Experience with Inter-municipal Cooperative Partnerships

Abstract

:1. Introduction

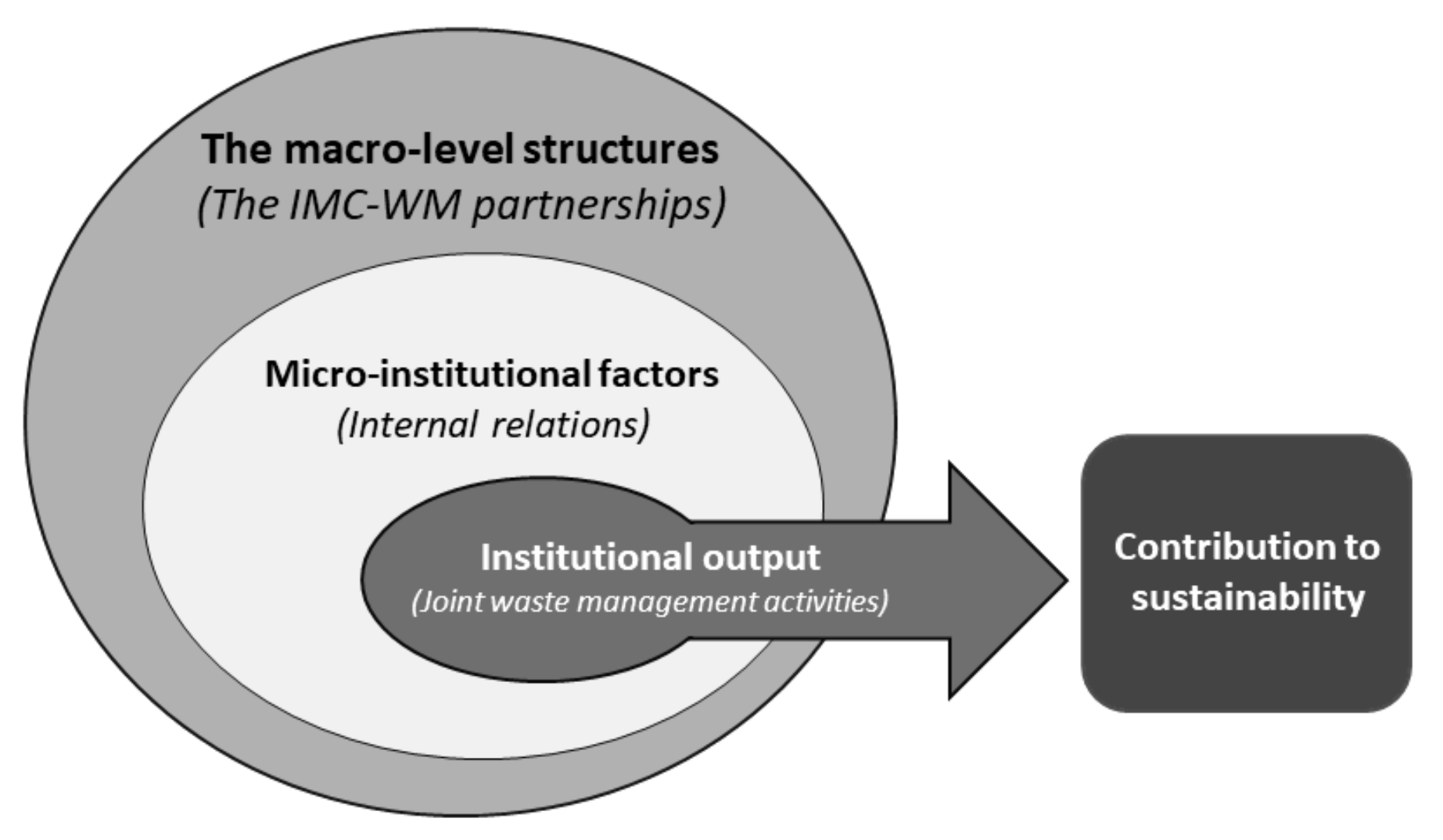

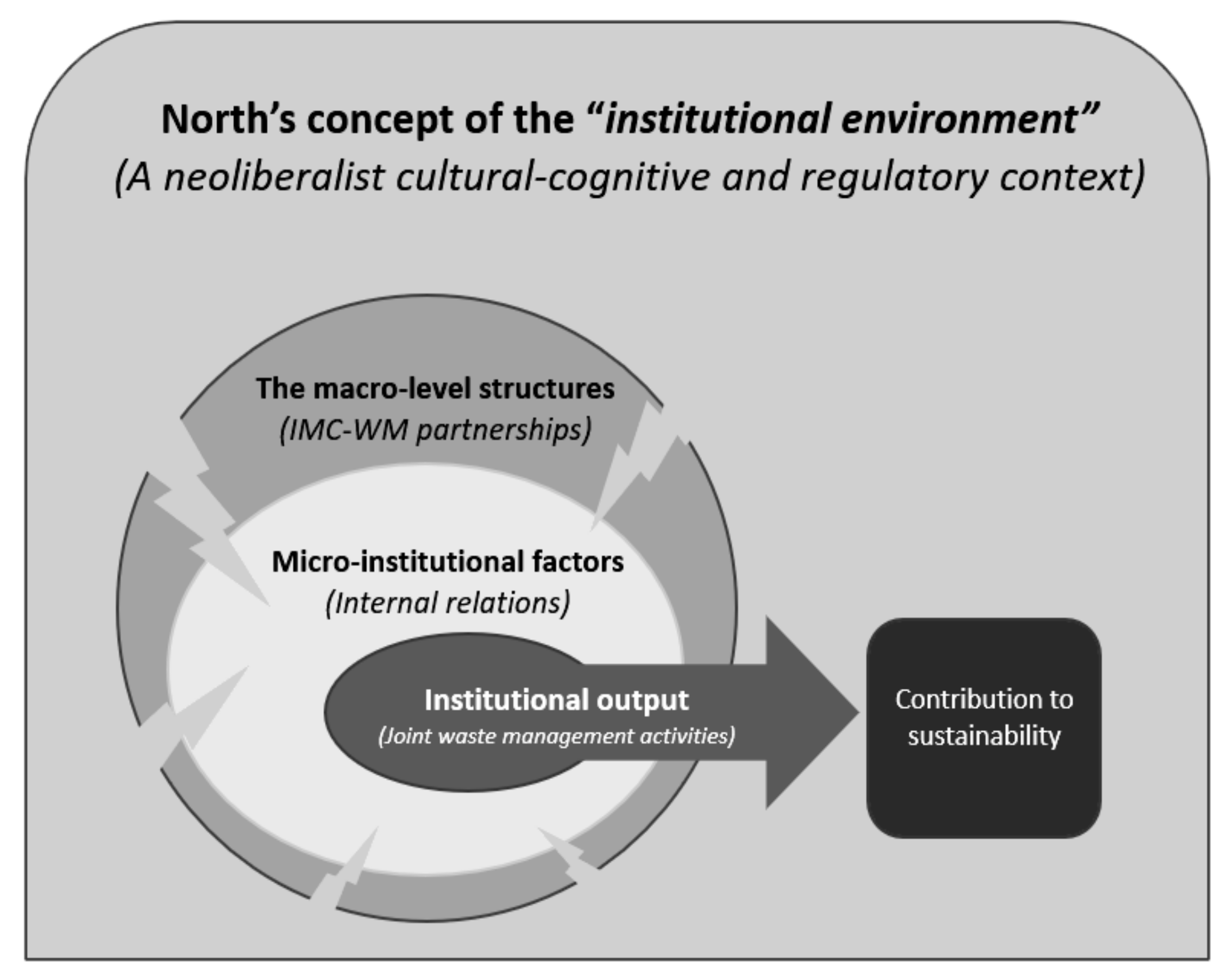

- the macro-level institutional structures that have emerged in Australia to facilitate cooperation;

- the institutional outputs (joint waste management and policy activities) which they are facilitating; and

- how the attitudes and engagement dynamics that exist within these partnerships shape their effectiveness.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Local Government, Waste Management and Administrative Borders

2.2. The Value of Regional Partnerships in Enabling the National Waste Policy 2018

2.3. Regional Engagement, Mechanisms, and Conditions

- The nature of problems: When problems have a high degree of complexity or are wicked problems such as waste management, they can present a challenge for a single authority to effectively address.

- History of previous collaboration: In the Australian context, a legacy exists of strong 1970s and 1980s regionalist policies [29] that are relevant to current and future IMC-WM partnership formations.

- Identity and territorial context: The idea that shared identity can act as a condition to forming waste partnerships is supported in the findings of Kołsut [30].

- Balanced power relations: A previous study found IMC-WM partnerships which feature one council of a disproportionately larger population are less efficient [31].

- Institutional context: The variation of waste levy programs between Australian states affirms the idea that regulatory incentives are a strong precursor condition to cooperation. For example, in New South Wales (NSW), a portion of levy funds is provided to support IMC-WM partnerships through the Waste Less, Recycle More fund [32].

- External influence: The acute challenges that many Australian councils have experienced following the ramifications of the China National Sword policy [33] could perhaps be considered a prime precursor condition for cooperative engagement.

- Expected outcomes: The view that IMC-WM partnerships save councils costs is supported by a recent meta-regression analysis study undertaken by Bel and Sebo [25].

- Organisation profile: Leadership styles, administrative and public management profiles, organisational culture and norms, and decision-makers’ risk-taking attitude can create the disposition or institutional ability towards collaboration in the waste management sector.

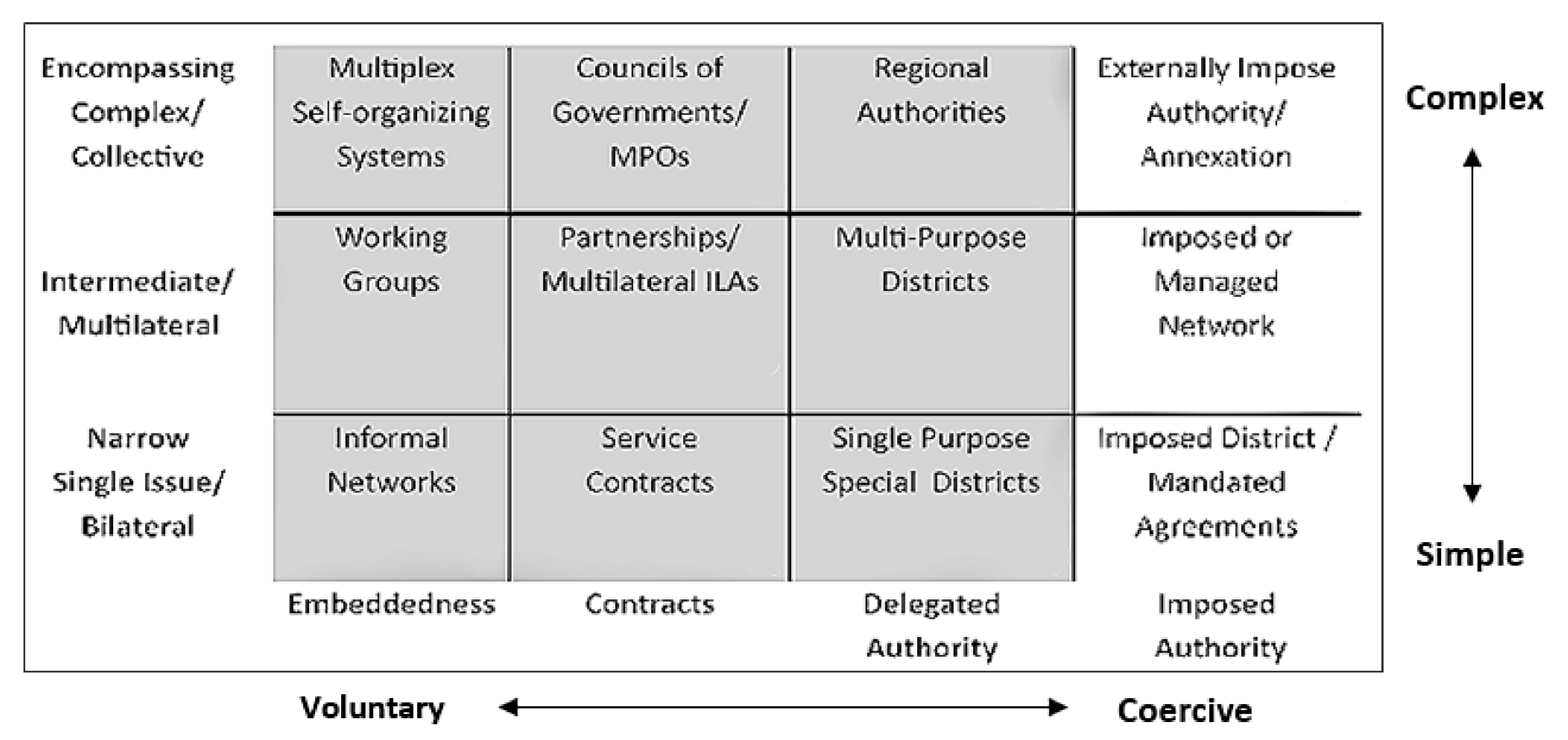

2.4. Institutional Dimensions of IMC Partnerships

2.5. Existing Empirical Research into Australia’s ‘Shared Services’ Experience

2.6. Governance Paradigms and Internal Relations

2.7. Pitfalls to Regional Cooperation

2.7.1. The Multiple Principal Problem

2.7.2. Deficits in Social Capital between Network Partners

2.8. Key Findings from the Literature

- RQ1: What institutions and engagement practices exist in Australia to support regional cooperation in waste management?

- RQ2: What are the outputs (joint waste management activities) arising through these partnerships?

- RQ3: What are the internal relations and attitudinal characteristics of the municipal policy actors engaged in regional cooperation, and what are their implications for sustainability?

3. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

4. Research Methodology and Methods

- A nationwide census survey of Australia’s IMC-WM partnerships, and

- A questionnaire to the municipal policy actors participating in IMC-WM partnerships on behalf of their respective councils.

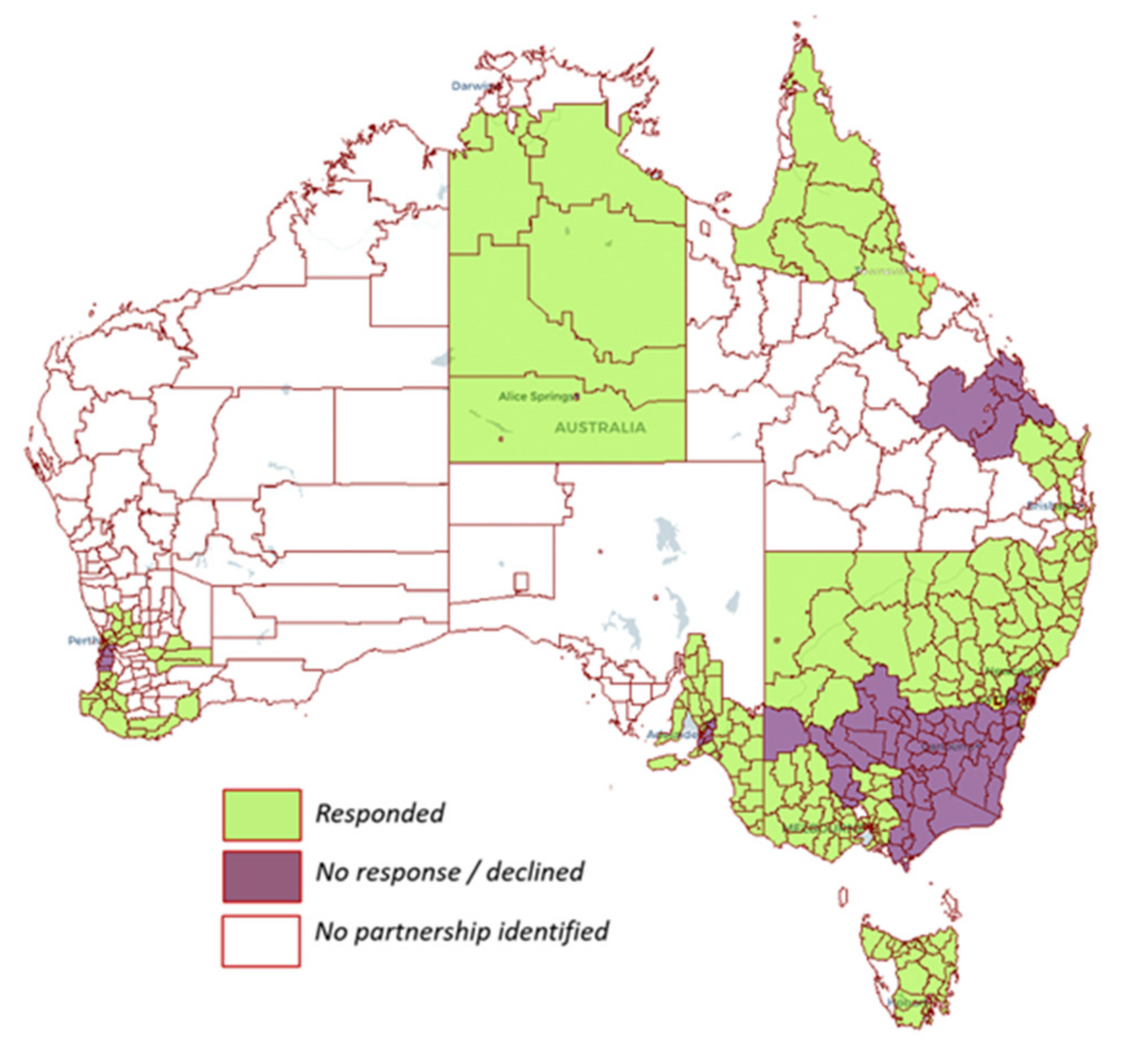

4.1. Census Survey and Participation Procedures

- a desktop review involving a review of each state or territory’s waste policy publications (e.g., strategy documents, waste grant recipient lists, etc.) to identify all State Government-recognised IMC-WM partnerships;

- phone and email inquiries to local government associations, waste industry associations and dominant local governments in a region;

- a ‘snowball’ strategy which entailed phoning remotely located IMC-WM partnerships and asking them to list all other remotely located IMC-WM partnerships they were aware of within their state.

4.2. IMC-WM Census Survey Response Rate

4.3. Design of Questionnaire to Municipal Policy Actors

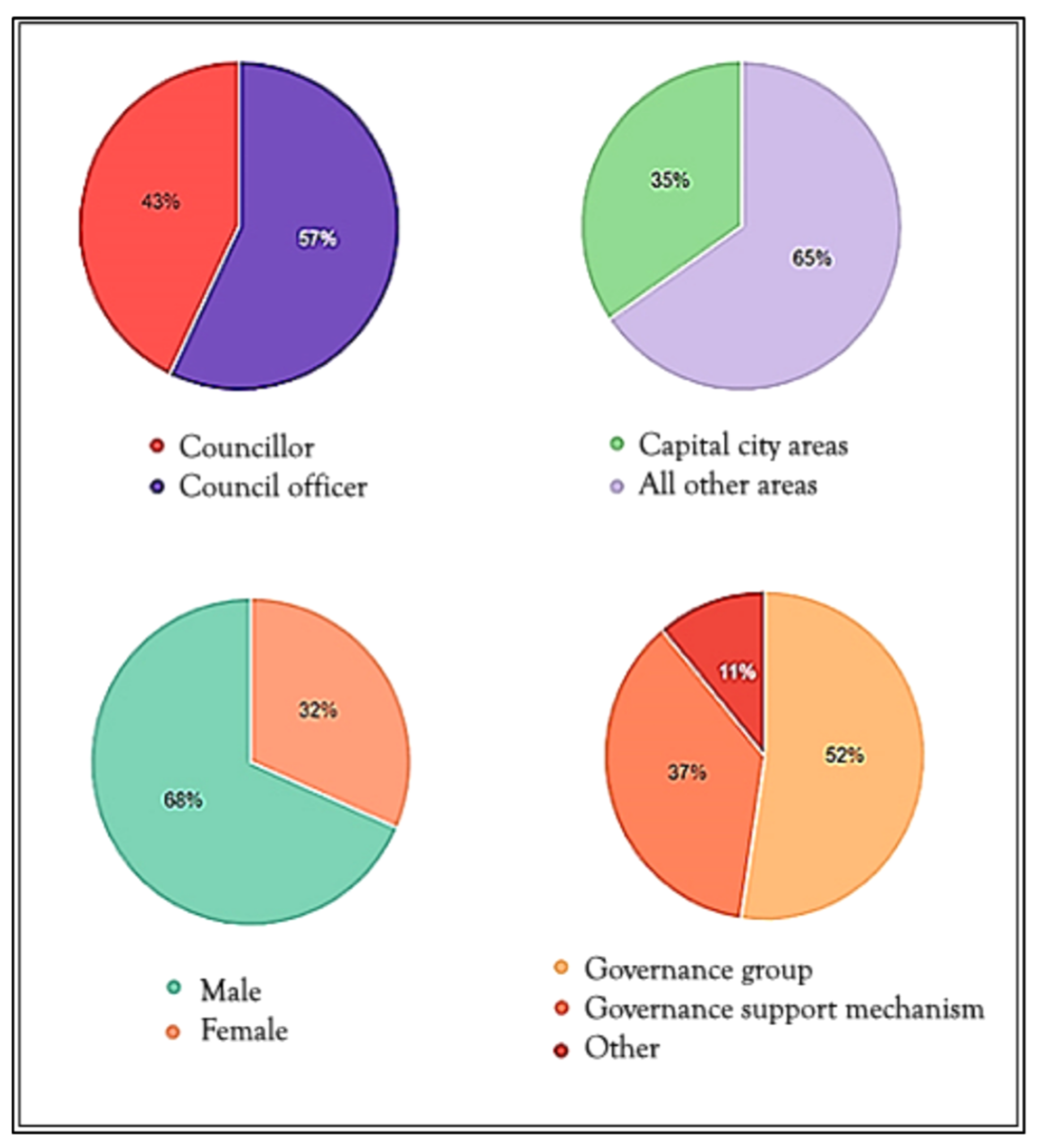

4.4. Questionnaire Response Rate

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Institutions and Engagement Practices to Support Regional Cooperation in Waste Management

5.1.1. Partnership Types

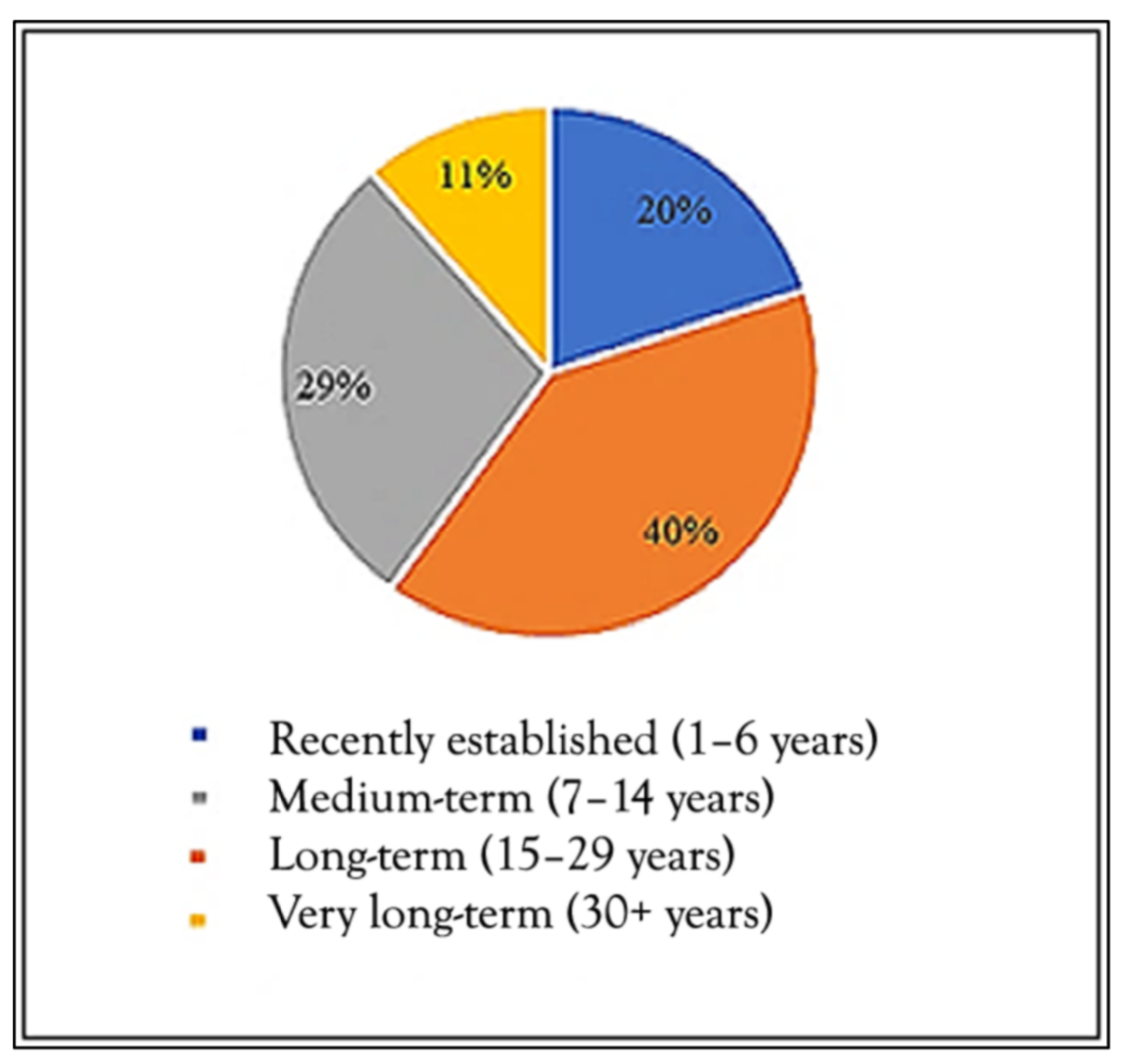

5.1.2. Membership and Years Together

5.1.3. Governance Arrangements

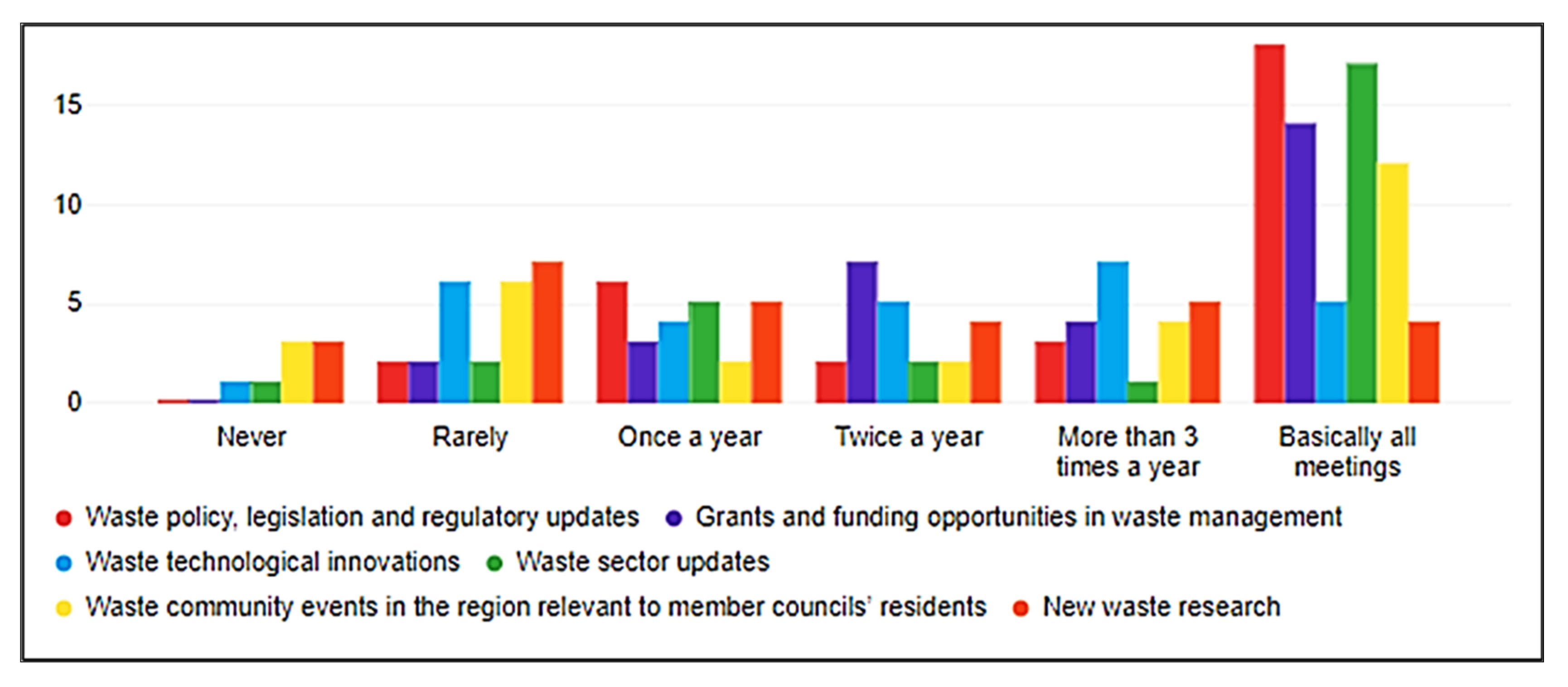

5.1.4. Regional Exchange of MSW Policy Updates and Other Information

5.1.5. Cross-Boundary Engagement Meetings

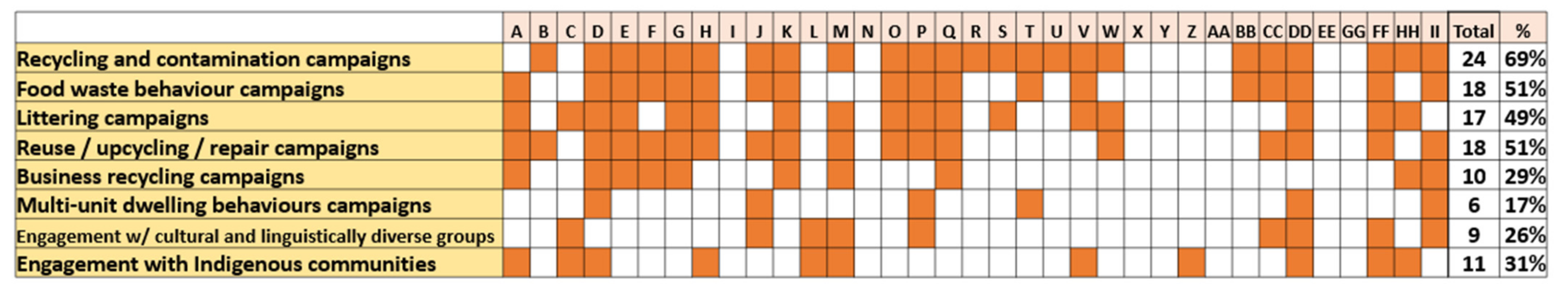

5.2. The Institutional Outputs (Joint Actions) Arising from Regional Cooperation

5.2.1. Frequency of Sharing among Waste Program Activities

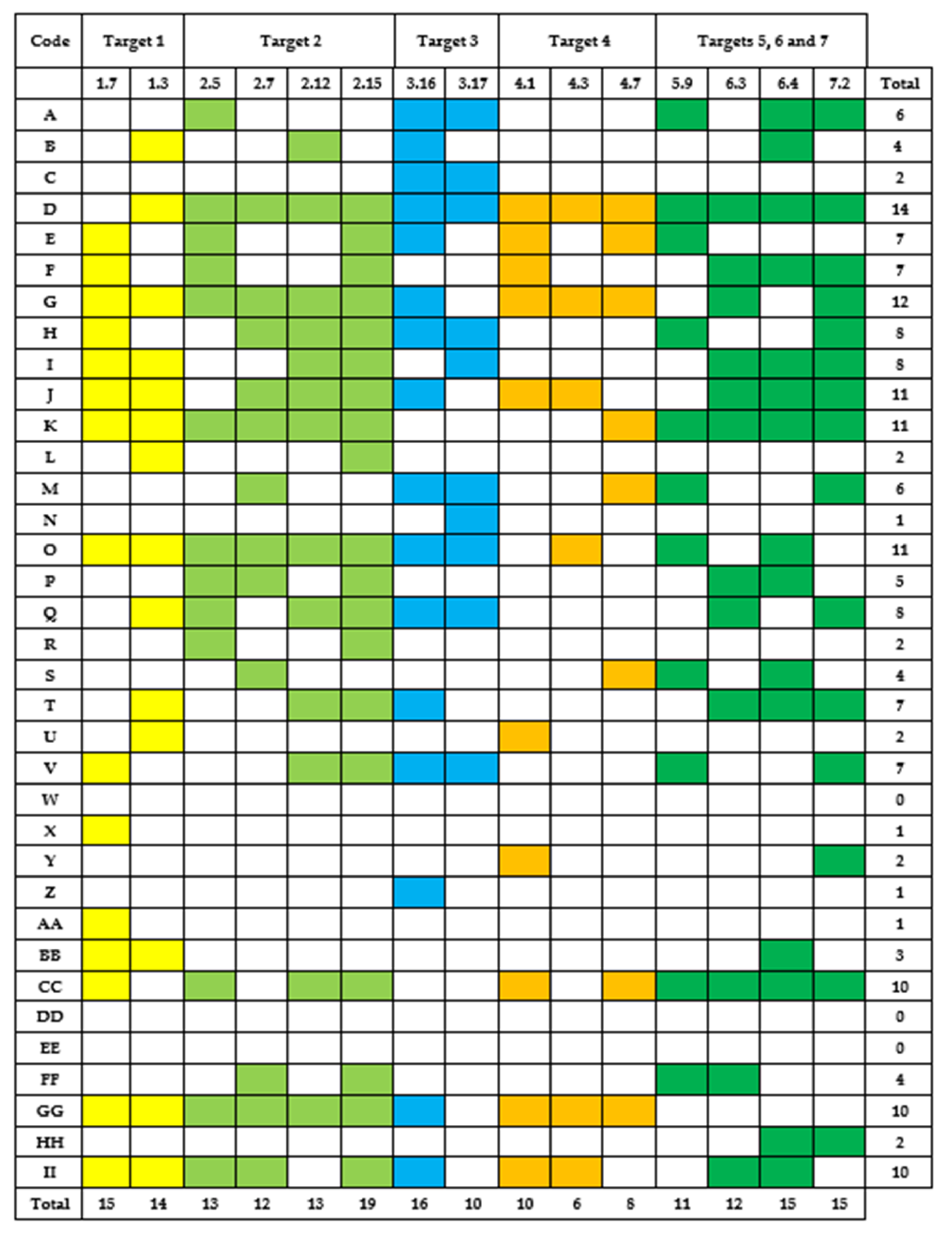

5.2.2. Contributions to the National Waste Policy 2018 Action Goals

“Five out of our 6 councils have FOGO (Food Organics/Garden Organics collection). We actively support promotion of this where possible and are currently running a major awareness raising campaign in three of our LGAs (grant funded). We regularly review data collection and aim to harmonise within the region (more than externally, but we do provide input to state government data review and requests).”—Regional Coordinator (NSW, Inner Regional context)

“We support the introduction of more services at Waste Transfer Stations, such as batteries, e-waste, globes, and tyres, by providing concessions for these services.”—Project Manager (TAS, Outer Regional, Inner Regional context)

“While we are not delivering a FOGO service directly, we are in the midst of a regional FOGO/FO feasibility study, which will assist councils to make decisions around services. We are planning to conduct a business case for an organics transfer station for multi-council benefit. We will soon deliver recommendations from a waste data and infrastructure planning project, which examines regional material flows, current infrastructure capacity, and projected flows over the next 20 years to identify, which includes recommendations for a standardised waste data protocol for MSW, including illegal dumping, and options for adoption of smart technology to streamline data and improve quality.”—Regional Coordinator (NSW, Metropolitan context)

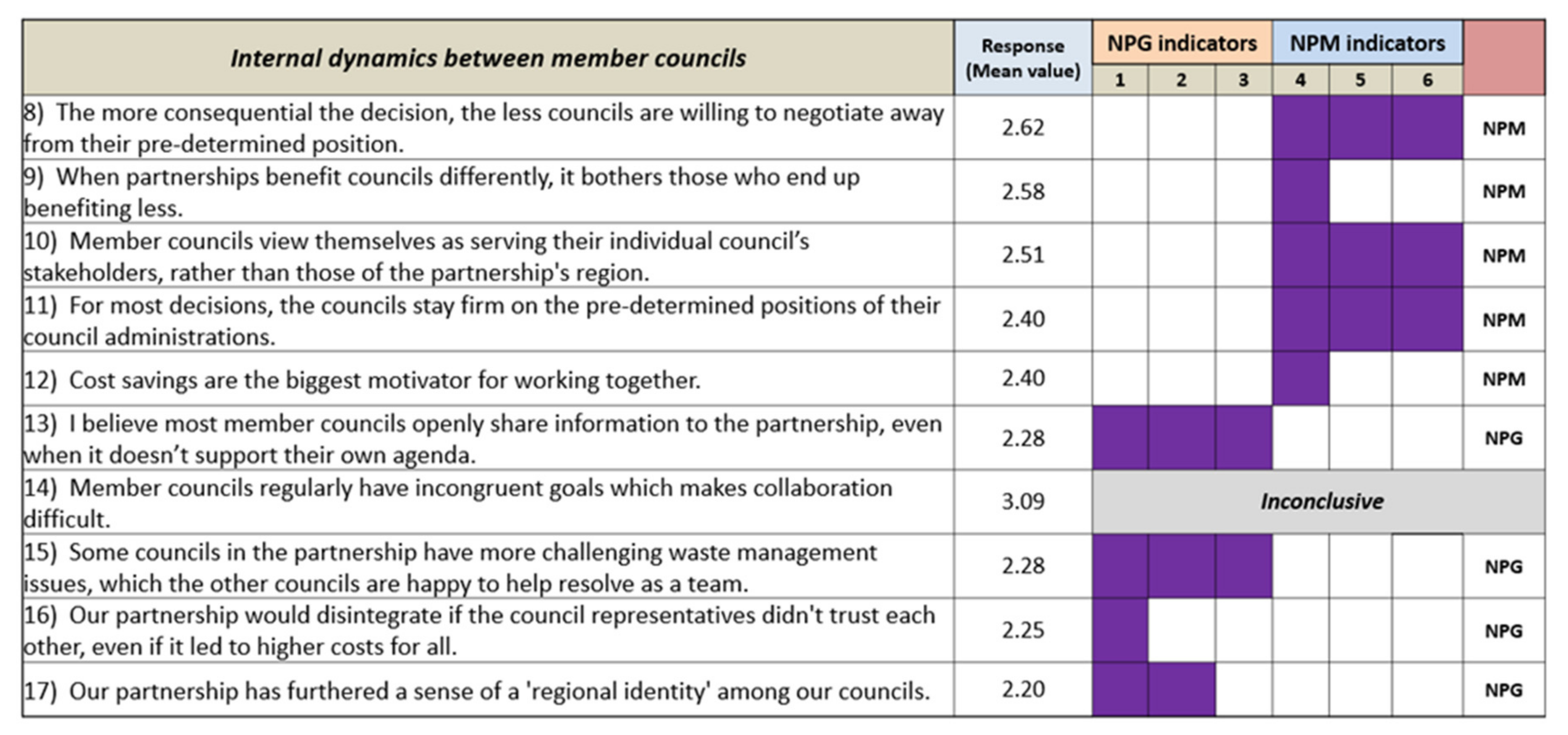

5.3. Internal Relations among the Participants Engaged in Regional Cooperation

- the personal attitudes held by the municipal policy actors (the councillors, executives and council officers engaged in regional cooperation) toward the complexity of waste policy and the need for a regional approach;

- the engagement dynamic taking place within IMC-WM partnerships, and whether a culture of competitiveness or of collaborativeness exists between member councils.

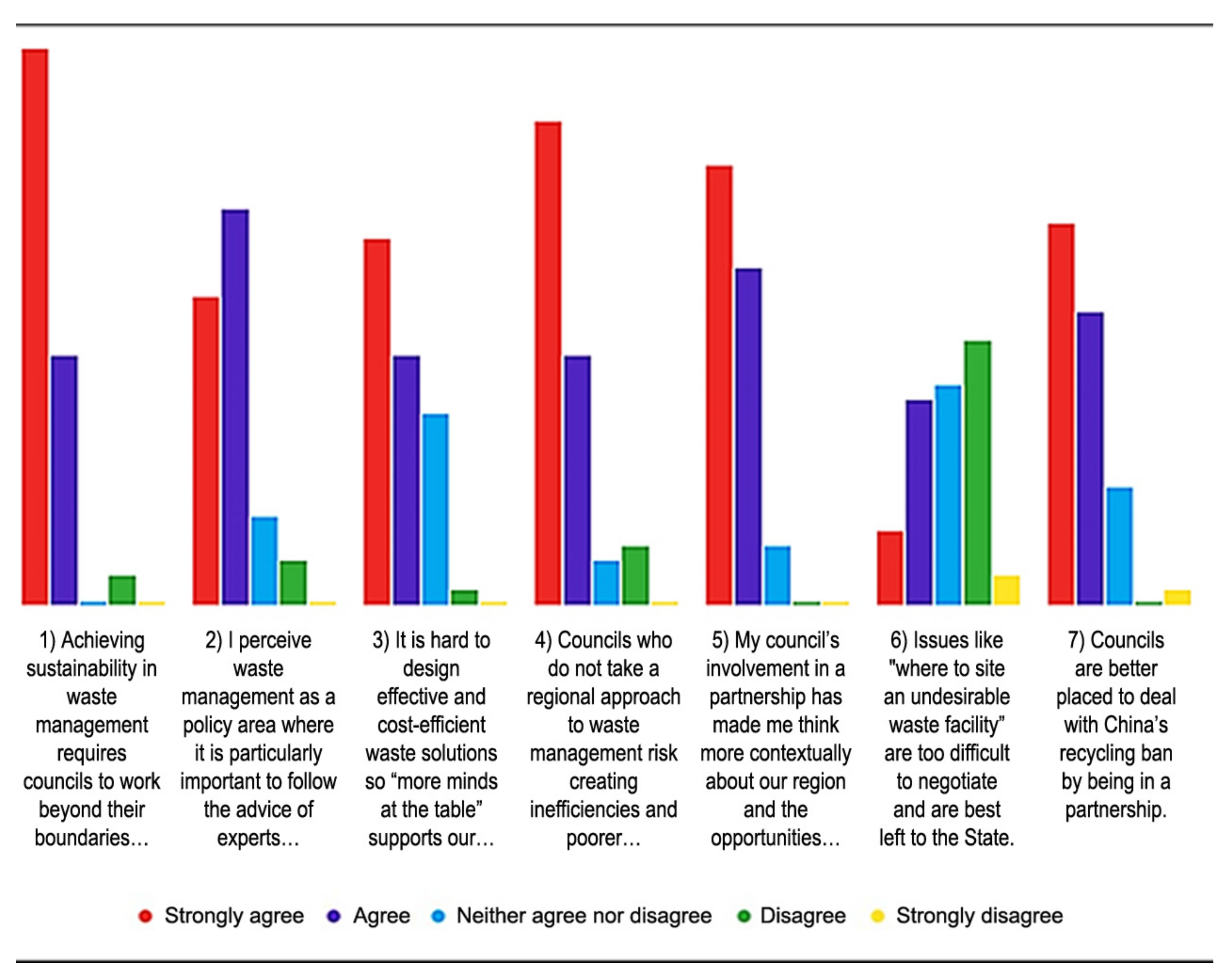

5.3.1. Participants’ Attitudes toward Complexity and Regional Cooperation

“Working together and advocating for regions is critical in continuous improvement. Regions are more adaptable, professional and deliver better outcomes (than State Governments).”—Regional Coordinator, Victoria

“Working together regionally provides broad consistency in waste management initiatives and develops economy of scale which can aid with cost savings.”—Regional Coordinator, Tasmania

“For small municipalities like ours, it is important to build and maintain trust between the players to access economies of scale, allow decisions to be made from a basis of a clear understanding of issues and maintain consistency in communications and service delivery.”—Regional Coordinator, Western Australia

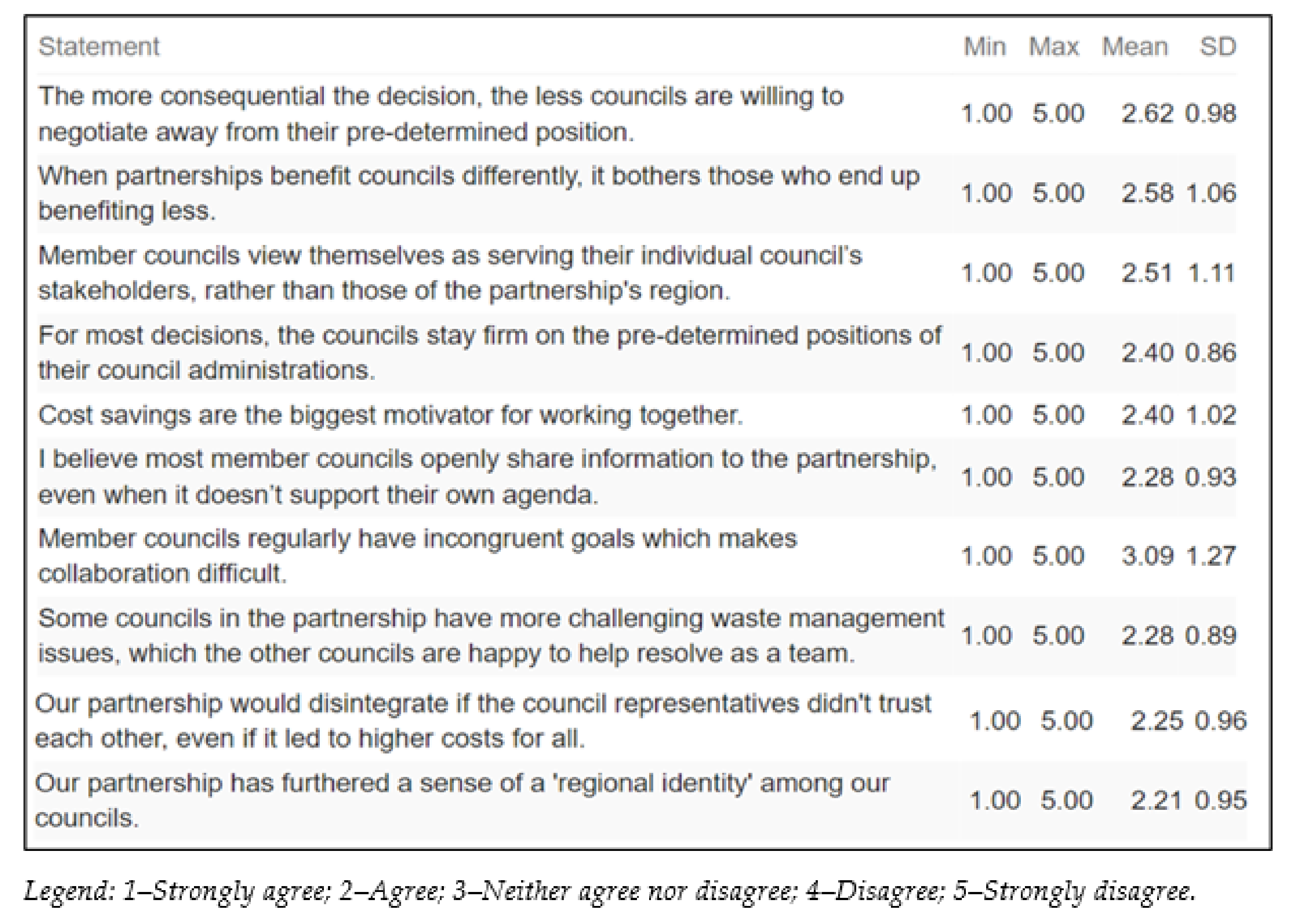

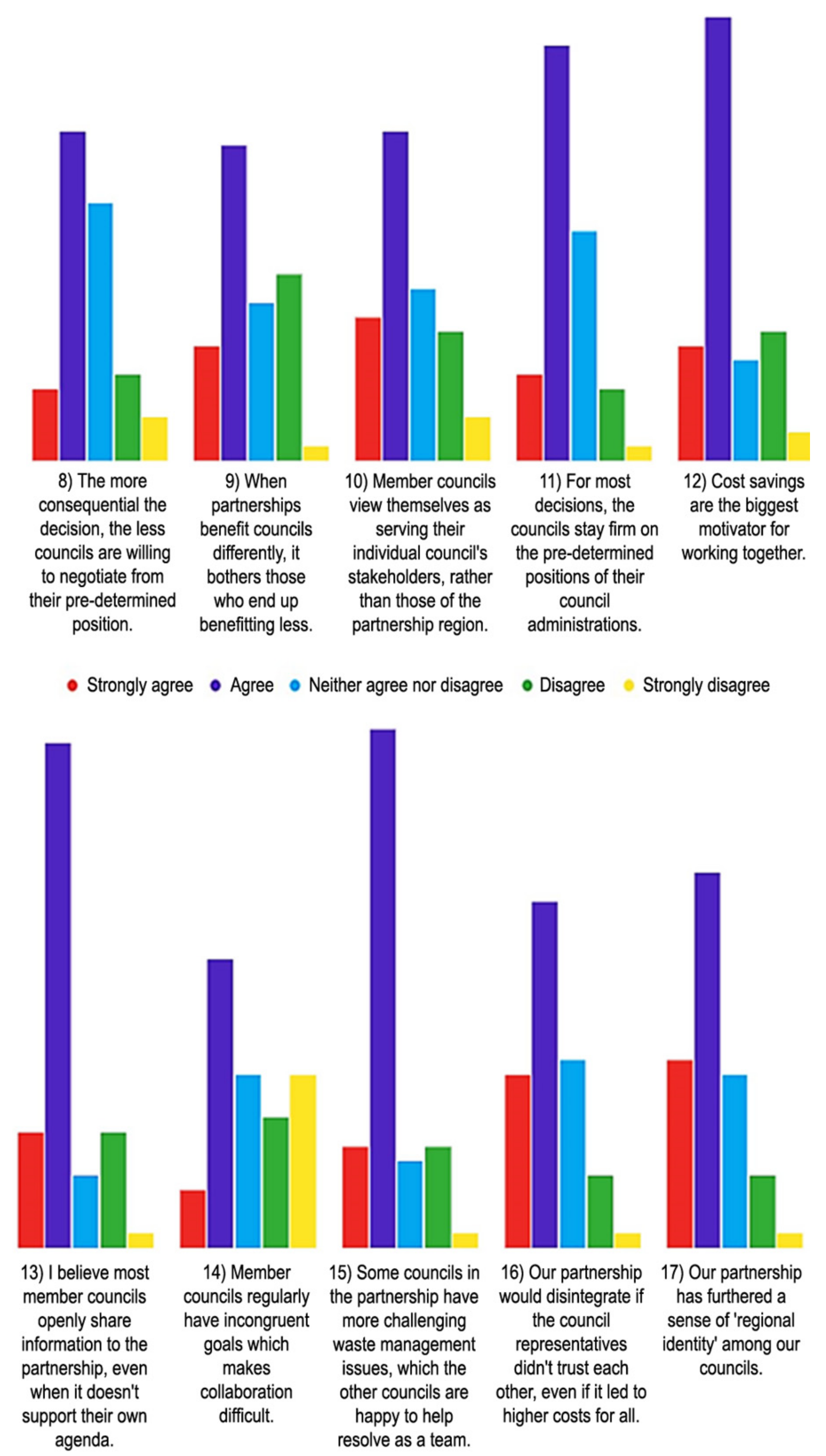

5.3.2. Competitive or Collaborative? Indications on the Engagement Dynamic Inside the Partnerships

“Share information and have an open mind—but beware of hidden agendas that might shape the actions of some Councils, Councillor representatives or officers.”—Council officer, Western Australia

“There is a lot of arrogance with the councils and a lot of fear—not wanting to collaborate on a project as they believe they will miss out and some other Council will get more benefit from the project than they do.”—Regional Coordinator, (State context withheld)

“Individual Council ambitions can be a barrier to commitment to regional infrastructure.”—Regional Coordinator, (State context withheld)

6. Conclusions and Reflections

- participants commonly display attitudes which recognise the virtues and capabilities of regional cooperation in achieving sustainability in waste management; and

- participants commonly engage in a relational dynamic rooted in competitiveness that is antithetical to these virtues and capabilities.

“The NPM is not dead, or even comatose... Elements of NPM have been absorbed as the normal way of thinking by a generation of public officials. Many NPM-ish organisational structures remain firmly standing. By the standards of previous administrative fashions—even by comparison with the spread of Weberian bureaucracy itself—NPM must be accounted a winning species in terms of its international propagation and spread.”—Pollitt, 2007 [74]

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire to Municipal Policy Actors Participating in Regional Partnerships

- 1.

- Select your State/Territory

- ○

- Tasmania (TAS)

- ○

- Queensland (QLD)

- ○

- New South Wales (NSW)

- ○

- Northern Territory (NT)

- ○

- South Australia (SA)

- ○

- Western Australia (WA)

- ○

- Victoria (Vic)

- ○

- Australian Capital Territory (ACT)

- 2.

- Your geographic context

- ○

- Capital city area

- ○

- All other areas

- 3.

- Are you a Councillor or a Council Officer?

- ○

- Councillor

- ○

- Council Officer

- 4.

- Gender

- ○

- Male

- ○

- Female

- ○

- Other

- 5.

- How do you mainly participate in the partnership?

- ○

- Governance group (e.g., a Board, Steering Committee, Regional Waste Group, etc.)

- ○

- Governance support mechanism (e.g., a Forum, Technical Committee, etc.)

- ○

- Other

Comments/clarification: ____________________ - 6.

- To what degree do you agree with the following statements.Scale: Strongly agree—Agree—Neither agree nor disagree—Disagree—Strongly disagreeStatement group 1

- ❖

- Our partnership has furthered a sense of a ‘regional identity’ among our councils.

- ❖

- Member councils regularly have incongruent goals which makes collaboration difficult.

- ❖

- For most decisions, the councils stay firm on the pre-determined positions of their council administrations.

- ❖

- Our partnership would disintegrate if the council representatives didn’t trust each other, even if it led to higher costs for all.

- ❖

- Cost savings are the biggest motivator for working together.

- ❖

- The more consequential the decision, the less councils are willing to negotiate away from their pre-determined position.

- ❖

- I believe most member councils openly share information to the partnership, even when it doesn’t support their own agenda.

- ❖

- When partnerships benefit councils differently, it bothers those who end up benefiting less.

- ❖

- Member councils view themselves as serving their individual council’s stakeholders, rather than those of the partnership’s region.

- ❖

- Some councils in the partnership have more challenging waste management issues which the other councils are happy to help resolve as a team.

Statement group 2- ❖

- Achieving sustainability in waste management requires councils to work beyond their boundaries.

- ❖

- My council’s involvement in a partnership has made me think more contextually about our region and the opportunities therein.

- ❖

- Councils who do not take a regional approach to waste management risk creating inefficiencies and poorer environmental outcomes.

- ❖

- Councils are better placed to deal with China’s recycling ban by being in a regional partnership.

- ❖

- It is hard to design effective and cost-efficient waste solutions so “more minds at the table” supports our success.

- ❖

- I believe waste management is a policy area where it is particularly important to follow the advice of technical experts.

- ❖

- Issues like “where to site an undesirable waste management facility” are too difficult to negotiate between councils and are best left to the State Government.

- 7.

- From your experience, what advice would you give councils considering regional cooperation to address their waste issues?

- 8.

- Final thoughts. Please share any other thoughts you have on this topic.

Appendix B. Nationwide Census Survey to Regional Partnerships for Waste Management

| Section 1: Organisational Characteristics |

| Select your State/Territory |

| ○ TAS |

| ○ QLD |

| ○ NSW |

| ○ NT |

| ○ SA |

| ○ WA |

| ○ VIC |

| ○ ACT |

| How many member councils (aka ‘constituent councils’) are there in your partnership? |

| If you have a voting system to make decisions between member councils, what is each council’s voting power? |

| ○ Equal voting power per member council |

| ○ Variation in voting power, dependent on the population of each council |

| ○ Variation in voting power, depending on financial contribution to the partnership |

| ○ Other governance system: |

| ○ Non-applicable |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| Approximately how many years has the partnership been operating? |

| For waste groups within regional associations of councils, please answer on how long the waste group itself has been operating. |

| ○ 1–3 years |

| ○ 4–6 years |

| ○ 7–9 years |

| ○ 10–14 years |

| ○ 15–19 years |

| ○ 20–29 years |

| ○ 30+ years |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

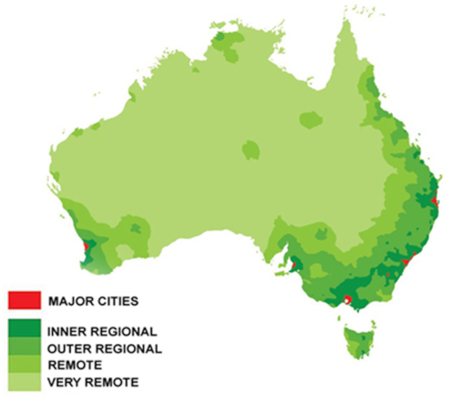

| Using the map below, estimate the ‘remoteness’ mix of your partnership’s area. |

|

| Example: “About 40% Inner Regional and 60% Outer Regional” |

| Your estimate: |

| Section 2: Jointly actioned waste management activities |

| Does the partnership deliver communication campaigns for its member councils? |

| Please tick all that apply |

| ▢ Recycling and contamination campaigns |

| ▢ Food waste behaviour campaigns |

| ▢ Littering campaigns |

| ▢ Reuse/upcycling/repair campaigns |

| ▢ Business recycling campaigns |

| ▢ Multi-unit dwelling behaviours campaigns |

| ▢ Engagement with cultural and linguistically diverse groups |

| ▢ Engagement with Indigenous communities |

| ▢ Other/s: ________________________________________________ |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

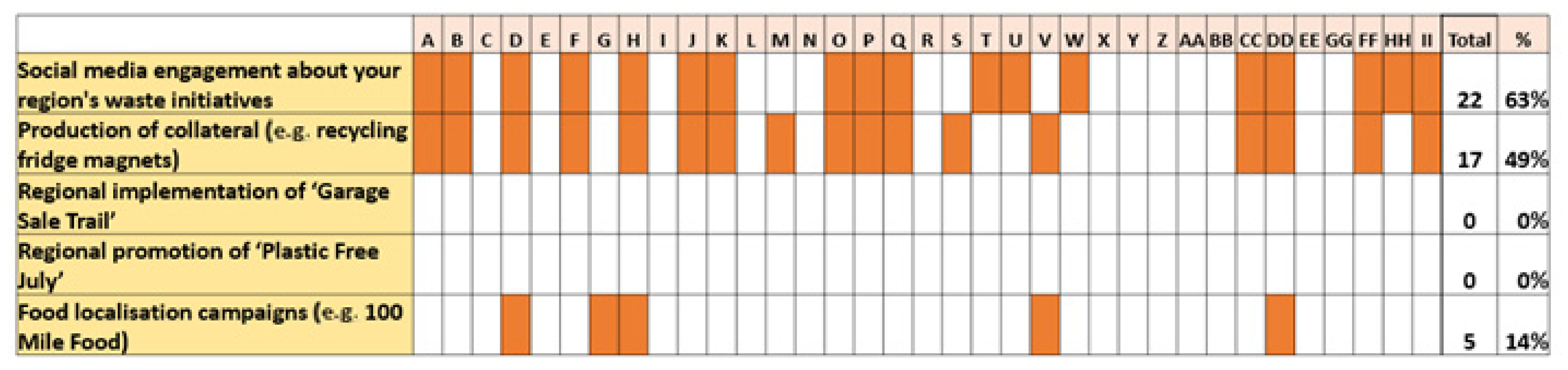

| Does the partnership undertake any other joint communication? |

| Please tick all that apply |

| ▢ Social media engagement about your region’s waste initiatives |

| ▢ Production of collateral |

| ▢ Regional implementation of ‘Garage Sale Trail’ |

| ▢ Regional promotion of ‘Plastic Free July’ |

| ▢ Food localisation campaigns (e.g., 100 Mile Food) |

| ▢ Other/s: ________________________________________________ |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

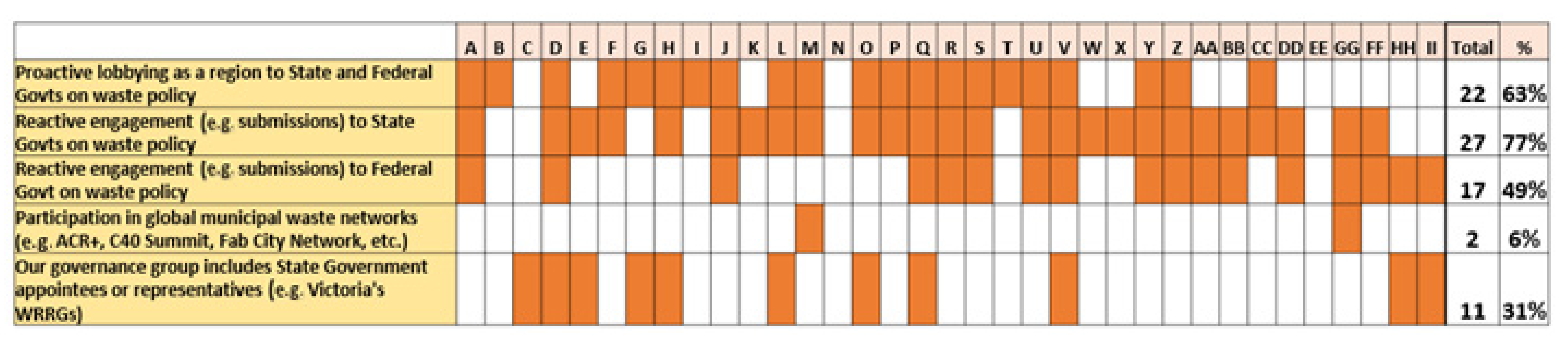

| Does the partnership engage with higher levels of government? |

| Please tick all that apply |

| ▢ We proactively lobby as a region to State and Federal Governments about waste policy |

| ▢ Reactive engagement (e.g., submissions) to State Governments on waste policy |

| ▢ Reactive engagement (e.g., submissions) to Federal Governments on waste policy |

| ▢ Participation in global municipal waste networks (e.g., ACR+, C40 Summit, etc.) |

| ▢ Our governance group includes State Government appointees or representatives |

| ▢ Other/s: ________________________________________________ |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

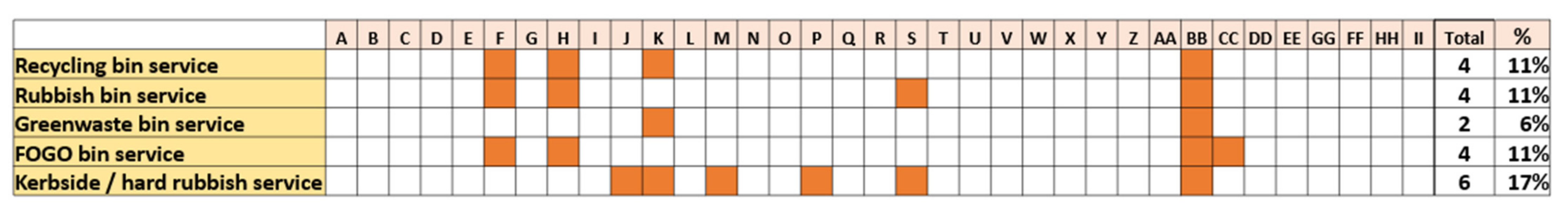

| Does the partnership manage any collection services? |

| Please tick all that apply |

| ▢ Recycling bin service |

| ▢ Rubbish bin service |

| ▢ Green waste bin service |

| ▢ FOGO bin service |

| ▢ Kerbside/hard rubbish service |

| ▢ Other/s: ________________________________________________ |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

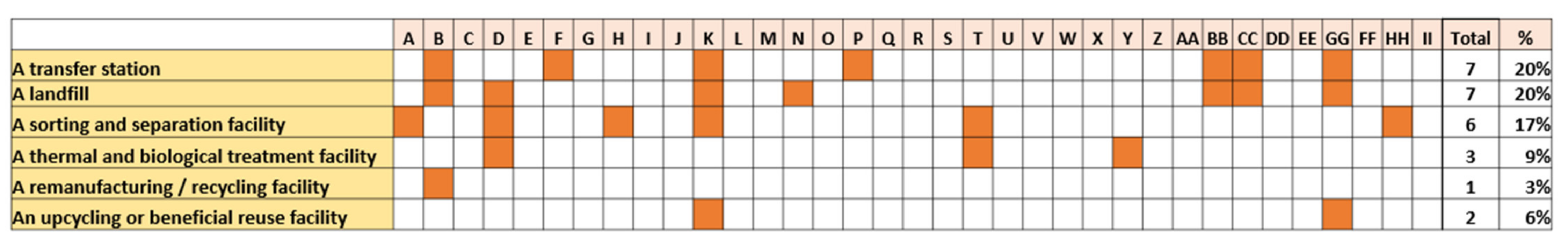

| Does the partnership facilitate the shared use of any waste facilities? |

| This could be the partnership managing the facility OR one member council allowing access of its facility to the others. |

| Please tick all that apply |

| ▢ A transfer station |

| ▢ A landfill |

| ▢ A sorting and separation facility (e.g., material recovery facility) |

| ▢ A thermal and biological treatment facility |

| ▢ A remanufacturing/recycling facility |

| ▢ An upcycling or beneficial reuse facility |

| ▢ Other/s: ________________________________________________ |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

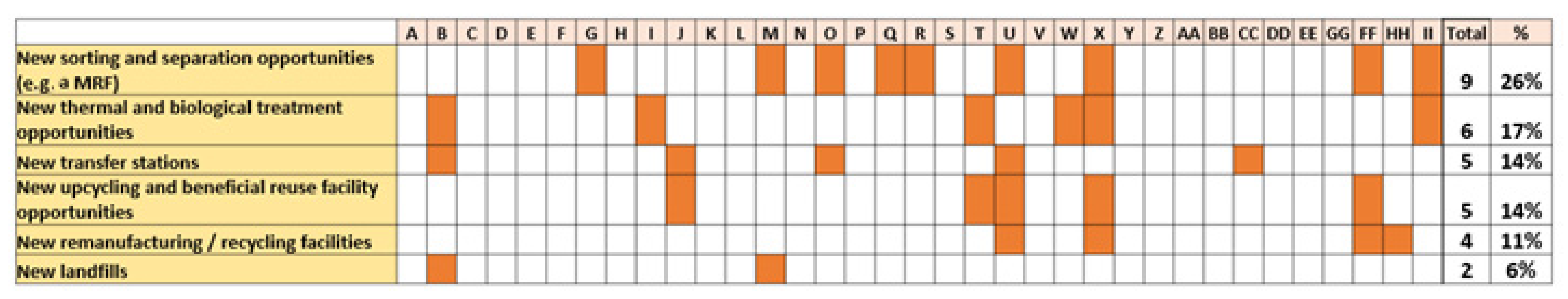

| Is the partnership working together on any joint Expression of Interest (EOI) activities or market sounding? |

| Please tick all that apply |

| ▢ New sorting and separation opportunities (e.g., a new material recovery facility) |

| ▢ New thermal and biological treatment opportunities |

| ▢ New transfer stations |

| ▢ New upcycling and beneficial reuse facility opportunities |

| ▢ New remanufacturing/recycling facilities |

| ▢ New landfills |

| ▢ Other/s: ________________________________________________ |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

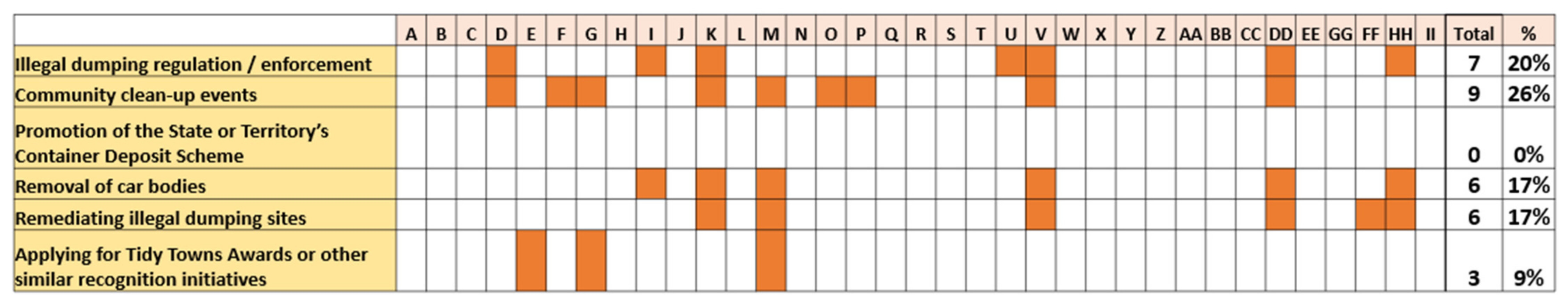

| Does the partnership work together to address littering and/or illegal dumping? |

| Please tick all that apply |

| ▢ Illegal dumping regulation/enforcement |

| ▢ Community clean-up events |

| ▢ Promotion of your State or Territory’s Container Deposit Scheme |

| ▢ Removal of car bodies |

| ▢ Remediating illegal dumping sites |

| ▢ Applying for Tidy Towns Awards or other similar recognition initiatives |

| ▢ Other/s: ________________________________________________ |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

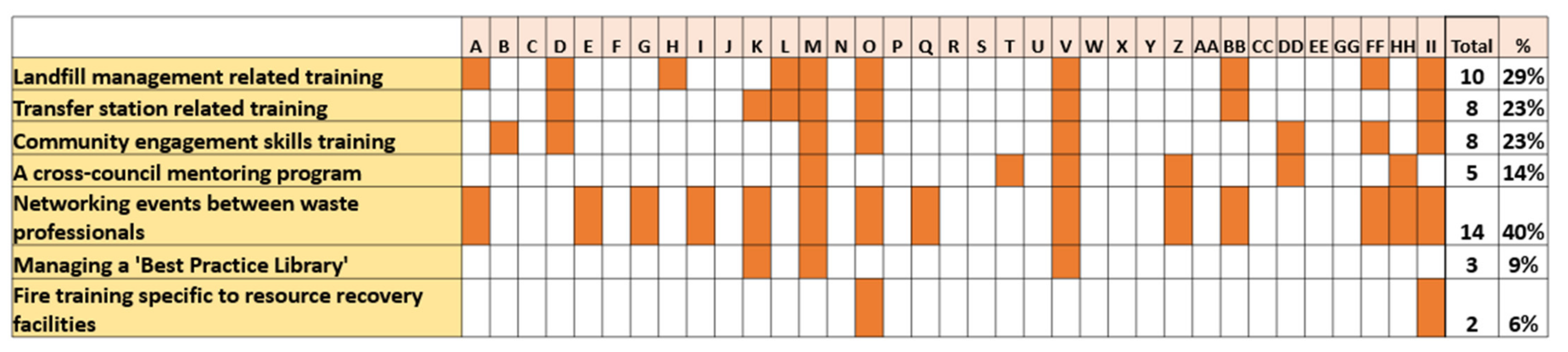

| Does the partnership organise training or professional development for member councils’ staff? |

| Please tick all that apply |

| ▢ Landfill management related training |

| ▢ Transfer station related training |

| ▢ Community engagement skills training |

| ▢ A cross-council mentoring program |

| ▢ Networking events between waste professionals |

| ▢ Managing a ‘Best Practice Library’ |

| ▢ Fire training specific to resource recovery facilities |

| ▢ Other/s: ________________________________________________ |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

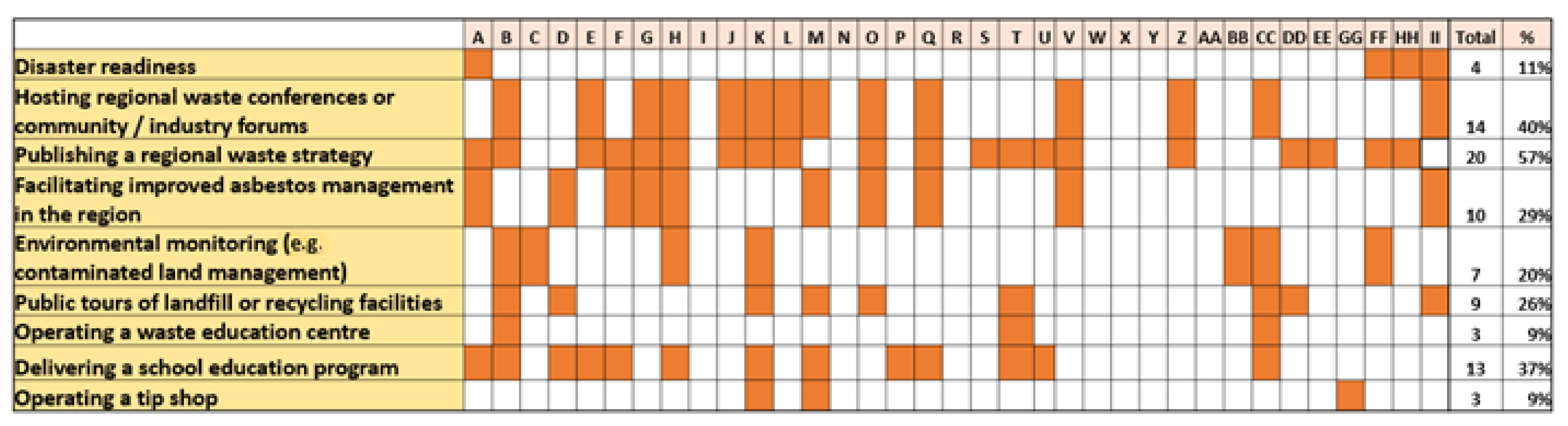

| Does the partnership facilitate any of these activities? |

| Please tick all that apply |

| ▢ Disaster readiness |

| ▢ Hosting regional waste conferences or community/industry forums |

| ▢ Publishing a regional waste strategy |

| ▢ Facilitating improved asbestos management in the region |

| ▢ Environmental monitoring (e.g., contaminated land management) |

| ▢ Public tours of landfill or recycling facilities |

| ▢ Operating a waste education centre |

| ▢ Delivering a school education program |

| ▢ Operating a tip shop |

| ▢ Other/s: ________________________________________________ |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

| Section 3: Optional upload of documents |

| To help us understand your partnership better, you have the option here to upload any corporate documents you wish to share, such as your Memorandum of Understanding or regional strategy. |

| Upload function: |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| Section 4: The National Waste Policy 2018 |

| Since 2018, has your regional partnership been active in any of the following areas? |

| Target 1 |

| ▢ Supporting the development of new markets for recycled products and materials in the region |

| ▢ Procurement initiatives to support more recycled content in the procurement decisions of the member councils or the partnership |

| ▢ New regulations in the region to prevent the landfilling of recyclable plastic, paper, glass or tyres |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

| Target 2 |

| ▢ Programs to help businesses in your region to identify opportunities to reduce their waste |

| ▢ Providing support to community-based reuse and repair centres in your region |

| ▢ Supporting circular economy principles in your region’s urban planning, infrastructure and development projects |

| ▢ Undertaking research to better understand the contributing factors to contamination in kerbside recycling bins |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

| Target 3 |

| ▢ Leveraging existing regional development programs to support better waste and resource recovery outcomes |

| ▢ Increasing access to waste and resource recovery infrastructure for regional, remote and Indigenous communities |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

| Target 4 |

| ▢ Growing the amount of recycled content used in road construction in the region |

| ▢ Increasing the uptake of recycled content in other government infrastructure projects |

| ▢ Supporting or promoting businesses who are applying circular economy practices, such as by running a recognition scheme or awards program |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

| Targets 5, 6 and 7 |

| ▢ Initiatives to improve the end-of-life disposal of products and articles containing hazardous substances |

| ▢ Delivering a FOGO service to your region or parts of it |

| ▢ Supporting infrastructure changes to facilitate future FOGO processing |

| ▢ Efforts to adjust your region’s waste data and reporting practices to support harmonisation with other jurisdictions |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| ____________________ |

| Section 5: Meetings, Knowledge Sharing, Viability |

| What types of regular meetings does the partnership host? |

| Common group/committee names are: General governance group, Technical Advisory Group, Professional Waste Officer Group, Waste Educators Group, etc. |

| Example answer: |

| General regional waste group—6 times a year |

| Waste educators group—4 times a year |

| In meetings, how often are these types of information shared with member councils? |

| ▪ Waste policy, legislation and regulatory updates |

| ▪ Grants and funding opportunities in waste management |

| ▪ Waste technological innovations |

| ▪ Waste sector updates |

| ▪ Waste community events in the region relevant to member councils’ residents |

| ▪ New waste research |

| ▪ Other: |

| Answer options: |

| ○ Never |

| ○ Rarely |

| ○ Once a year |

| ○ Twice a year |

| ○ More than 3 times a year |

| ○ Basically all meetings |

| Comments/clarification (optional): |

| __________________ |

| Section 6: Opportunities and challenges |

| What are the current barriers to your partnership enhancing sustainable waste management outcomes in your region? |

| ______________________ |

| Do you have any advice for regions considering forming an inter-municipal partnership to address their region’s waste issues? |

| ______________________ |

| Final thoughts. Please share any other thoughts you have from your experience with inter-municipal cooperation in waste management. |

| ______________________ |

Appendix C. Census Survey Results Summary of Institutional Characteristics

| Code | State | Legislative Mechanism | Institutional Context | Regional Context (Estimation) | Number of Member Councils | Governance Mechanism | Years Together |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | NSW | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation, Part of a statewide network of waste groups. | 40% Inner Regional, 60% Outer Regional | 6 | Equal voting power per member council | 15–19 years |

| B | WA | Statutory organisation | Regional local government, Part of a statewide network of waste groups. | 100% Inner Regional | 6 | Equal voting power per member council | 30+ years |

| C | NT | Voluntary grouping | Autonomous self-organised group. | 90% Very Remote, 10% Remote | 5 | Equal voting power per member council | 4–6 years (currently inactive) |

| D | NSW | Voluntary grouping | Autonomous self-organised group, Part of a statewide network of waste groups. | 100% Inner Regional | 7 | Equal voting power per member council | 20–29 years |

| E | TAS | Voluntary grouping | Autonomous self-organised group, Part of a statewide network of waste groups. | 60% Remote, 40% Inner Regional | 7 | Other governance process | 10–14 years |

| F | SA | Statutory organisation | Waste management authority. | 85% Inner Regional, 15% Remote | 4 | Equal voting power per member council | 10–14 years |

| G | VIC | Statutory organisation | State Govt agency, Part of a statewide network of waste groups. | 50% Inner Regional, 50% Outer Regional | 9 | Equal voting power per member council | 4–6 years |

| H | NSW | Voluntary grouping | Autonomous self-organised group, Part of a statewide network of waste groups. | 10% Inner Regional, 40% Outer Regional, 40% Remote, 10% Very Remote | 26 | Other governance process | 20–29 years |

| I | QLD | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation. | 40% Outer Regional, 30% Remote, 30% Very Remote | 13 | Equal voting power per member council | 15–19 years |

| J | NSW | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation, Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 100% Major city | 11 | Other governance process | 30+ years |

| K | TAS | Statutory organisation | Waste management authority, Part of a statewide network of waste groups. | 50% Inner Regional, 50% Outer Regional | 7 | Equal voting power per member council | 10–14 years |

| L | WA | Voluntary grouping | Investment-oriented network of councils, Autonomous self-organised group. | 50% Inner Regional, 50% Outer Regional. | 13 | Other governance process | 10–14 years |

| M | NT | Voluntary grouping | Autonomous self-organised group. | 95% Very Remote, 5% Remote | 3 | Other governance process | 4–6 years (currently inactive) |

| N | WA | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation | 100% Remote | 4 | Equal voting power per member council | 10–14 years |

| O | VIC | Statutory organisation | State Govt agency, Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 90–100% Outer Regional | 6 | Equal voting power per member council | 7–9 years |

| P | WA | Statutory organisation | Regional local government, Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 100% Major city | 5 | Equal voting power per member council | 15–19 years |

| Q | VIC | Statutory organisation | State Govt agency, Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 40% Inner Regional, 60% Outer Regional | 12 | Other governance process | 7–9 years |

| R | TAS | Voluntary grouping | Autonomous self-organised group, Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 50% Inner Regional, 50% Outer Regional | 12 | Equal voting power per member council | 1–3 years |

| S | NSW | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation, Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 100% Major city | 8 | Equal voting power per member council | 20–29 years |

| T | WA | Statutory organisation | Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 100% Major city | 3 | Equal voting power per member council | 20–29 years |

| U | SA | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation | 100% Outer Regional | 7 | Equal voting power per member council | 7–9 years |

| V | NSW | Voluntary grouping | Autonomous self-organised group, Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 90% Outer Regional, 5% Inner Regional, 5% Remote | 12 | Equal voting power per member council | 20–29 years |

| W | QLD | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation | 50% Inner Regional, 50% Outer Regional | 6 | Equal voting power per member council | 7–9 years |

| X | QLD | Voluntary grouping | Investment-oriented network of councils, Autonomous self-organised group. | 80% Inner City, 20% Inner regional. | 5 | Other governance process | 1–3 years |

| Y | WA | Statutory organisation | Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 20% Major city, 80% Inner Regional | 6 | Equal voting power per member council | 10–14 years |

| Z | SA | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation, | 30% Inner Regional, 60% Outer Regional, 10% Remote | 15 | Equal voting power per member council | 20–29 years |

| AA | WA | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation. | 100% Inner Regional | 5 | Equal voting power per member council | 7–9 years |

| BB | SA | Statutory organisation | Waste management authority. | 100% Inner Regional | 4 | Equal voting power per member council | 10–14 years |

| CC | WA | Statutory organisation | Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 100% Major city | 6 | Equal voting power per member council | 30+ years |

| DD | NSW | Voluntary grouping | Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 80% Inner Regional, 20% Outer Regional | 3 | Other governance process | 1–3 years |

| EE | SA | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation | 90% Outer Regional, 10% Inner Regional. | 8 | Equal voting power per member council | 1–3 years |

| FF | WA | Statutory organisation | Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 100% Major city | 7 | Variation in voting power, depending on financial contribution to the partnership | 30+ years |

| GG | NSW | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation, Part of a statewide network of waste groups. | 10% Major city, 60% Inner Regional, 30% Outer Regional | 10 | Other governance process | 10–14 years |

| HH | QLD | Voluntary grouping | Embedded in a regional organisation | 100% Major city | 5 | Equal voting power per member council | 7–9 years |

| II | VIC | Statutory organisation | State Govt agency, Part of a statewide network of waste groups | 100% Major city | 31 | Equal voting power per member council | 15–19 years |

References

- Organisation for Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD). Environment at a Glance: Circular Economy, Waste and Materials; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, A.; Ahsan, T. Zero-Waste: Reconsidering Waste Management for the Future; Taylor & Francis Group: Milton, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781138219083. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government National Waste Policy-Less Waste, More Resources 2018. Available online: https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/d523f4e9-d958-466b-9fd1-3b7d6283f006/files/national-waste-policy-2018.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Hyder Consulting. Role and Performance of Local Government-Waste and Recycling Related Data Information. Available online: https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/42d277a1-1edd-4b48-977c-5beb591c0f0b/files/local-government.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Agranoff, R.; McGuire, M. Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments; Georgetown University Press: Washington DC, USA, 2004; ISBN 0878408967. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, S.P. The new public governance? Public Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J. Local Government Service Provision: A Survey of Council General Manager, Independent Inquiry into Local Government Inquiry; NSW Local Government and Shires Association: Sydney, Australia, 2005.

- BJA (Burow Jorgensen and Associates). The Systemic Sustainability Study: Best Practice Management and Administration, Report to the Western Australian Local Government Association Review Panel; BJA: Perth, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, T. Review of South Australian Local Government Joint Service Delivery Opportunities: Analysis of Council Responses to a Survey and Options for Implementation of Various Resource Sharing Measures; Tony Lawson Consulting: Adelaide, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dollery, B.; Kortt, M.A.; Drew, J. Fostering shared services in local government: A common service model. Australas. J. Reg. Stud. 2016, 22, 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Bajracharya, B. The Changing Role of Regional Organisation of Councils in Australia: Case Studies from Perth Metropolitan Region. Adv. 21st Century Hum. Settlements 2020, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viva, L.; Ciulli, F.; Kolk, A.; Rothenberg, G. Designing Circular Waste Management Strategies: The Case of Organic Waste in Amsterdam. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2020, 4, 2000023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals–United Nations Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- United Nations. Agenda 21-United Nations Conference on Environment & Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2019/05/nua-english.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Dollery, B.; Akimov, A.; Byrnes, J. Shared services in Australian Local Government: Rationale, alternative models and empirical evidence. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2009, 68, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Australian Financial Sustainability Review Board (SAFSRB). Rising to the Challenge; SAFSRB: Adelaide, Australia, 2005.

- House of Representatives SCEFPA. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics, Finance and Public Administration: Rates and Taxes: A Fair Share for Responsible Local Government (‘Hawker Report’); Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2003.

- Productivity Commission. Overview-Waste Management; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2006.

- Australian Government/Australian Local Government Association. National Waste Policy Action Plan 2019; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Downes, J. The Planned National Waste Policy Won’t Deliver a Truly Circular Economy. Available online: https://theconversation.com/the-planned-national-waste-policy-wont-deliver-a-truly-circular-economy-103908 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Council of Europe. Working Together: Intermunicipal Cooperation in Five Central European Countries; Open Society Foundations: Budapest, Hungary, 2011; ISBN 9789639719248. [Google Scholar]

- Teles, F. Local Governance and Intermunicipal Cooperation; Palgrave MacMillian: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781137445742. [Google Scholar]

- Bel, G.; Fageda, X.; Mur, M. Why Do Municipalities Cooperate to Provide Local Public Services? An Empirical Analysis. Local Gov. Stud. 2013, 39, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bel, G.; Sebő, M. Does Inter-Municipal Cooperation Really Reduce Delivery Costs? An Empirical Evaluation of the Role of Scale Economies, Transaction Costs, and Governance Arrangements. Urban Aff. Rev. 2021, 57, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). The Sustainable Development Goals-What Local Governments Need to Know; UCLG: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, O.J.; Pierre, J. Exploring the strategic region: Rationality, context, and institutional collective action. Urban Aff. Rev. 2010, 46, 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.A. Regional impulses. J. Urban Aff. 1997, 19, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N.; Dollery, B.; Witherby, A. Regional Organisations of Councils (ROCS): The Emergence of Network Governance in Metropolitan and Rural Australia? Australas. J. Reg. Stud. 2003, 9, 169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kołsut, B. Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Waste Management: The Case of Poland. Quaest. Geogr. 2016, 35, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soukopová, J.; Vaceková, G. Internal factors of intermunicipal cooperation: What matters most and why? Local Gov. Stud. 2018, 44, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New South Wales Environmental Protection Agency. Funding for Voluntary Regional Waste Groups. Available online: https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/working-together/grants/councils/voluntary-regional-waste-funding (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Jones, S. Establishing political priority for regulatory interventions in waste management in Australia. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 2020, 55, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keremane, G. Governance of Urban Wastewater Reuse for Agriculture: A Framework for Understanding and Action in Metropolitan Regions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 331955056X. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.; North, D. Institutional Change and American Economic Growth: A First Step Towards a Theory of Institutional Innovation. J. Econ. Hist. 1970, 30, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba Ferreira, M.E.; Dijkstra, A.G.; Aniche, L.Q.; Scholten, P. Towards a typology of inter-municipal cooperation in emerging metropolitan regions. A case study in the solid waste management sector in Ecuador. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1757185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. Comparative Federalism and Intergovernmental Agreements; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781315765167. [Google Scholar]

- Feiock, R.C. The institutional collective action framework. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. Understanding Governance: Ten Years On. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 1243–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooiman, J. Modern Governance: New Government-Society Interactions; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, S. The New Public Governance?: Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; ISBN 020386168X. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, H. From New Public Management to New Public Governance: The implications for a ‘new public service’. In The Three Sector Solution: Delivering Public Policy in Collaboration with not-for-Profits and Business; Gilchrist, J., Butcher, D., Eds.; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, A. The Rise and Fall of the Welfare State/Asbjørn Wahl; Irons translator, J., Ed.; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ANZSOG. Has New Public Management Improved Public Services? Available online: https://www.anzsog.edu.au/resource-library/research/has-new-public-management-improved-public-services (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Hood, C. A Public Management for all seasons? New Public Management. Public Adm. 1991, 69, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, K.; Verschraegen, G.; Gruezmacher, M. Strategy for collectives and common goods: Coordinating strategy, long-term perspectives and policy domains in governance. Futures 2021, 128, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorey, P. The Legacy of Thatcherism-Public Sector Reform. Obs. La Société Br. 2015, 17, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nasiritousi, N.; Hjerpe, M.; Linnér, B.-O. The roles of non-state actors in climate change governance: Understanding agency through governance profiles. Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2016, 16, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Gestel, N.; Kuiper, M.; Hendrikx, W. Changed Roles and Strategies of Professionals in the (co)Production of Public Services. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyndman, N.; Lapsley, I. New Public Management: The Story Continues. Financ. Account. Manag. 2016, 32, 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S. From New Public Management to Networked Community Governance? Strategic Local Public Service Networks in England. In The New Public Governance? Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham, C. The Challenge of Collaborative Governance. Public Manag. 2000, 2, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxham, C.; Vangen, S. Ambiguity, Complexity and Dynamics in the Membership of Collaboration. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 771–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voorn, B.; van Genugten, M.; van Thiel, S. Multiple principals, multiple problems: Implications for effective governance and a research agenda for joint service delivery. Public Adm. 2019, 97, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sørensen, R.J. Does dispersed public ownership impair efficiency? The case of refuse collection in Norway. Public Adm. 2007, 85, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollery, B.; Grant, B.; Crase, L. Love thy neighbour: A social capital approach to local government partnerships. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2011, 70, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development OECD Insights: Human Capital. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/insights/37966934.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Swain, N. Social Capital and its Uses. Eur. J. Sociol./Arch. Eur. Sociol./Eur. Arch. Für Soziologie 2003, 44, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Warner, M.E. Factors explaining inter-municipal cooperation in service delivery: A meta-regression analysis. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2016, 19, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conway, M.-L.; Dollery, B.; Grant, B. Shared Service Models in Australian Local Government: The fragmentation of the New England Strategic Alliance 5 years on. Aust. Geogr. 2011, 42, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western Australian Local Government Association (WALGA). Cooperation and Shared Services; WALGA: Perth, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Generowicz, A.; Kowalski, Z.; Kulczycka, J. Planning of Waste Management Systems in Urban Area Using Multi-Criteria Analysis. J. Environ. Prot. (Irvine. Calif). 2011, 2, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blue Environment. National Waste Report 2020; Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Klundert, A.; Anschutz, J. Integrated Sustainable Waste Management-The Concept: Tools for Decision-Makers: Experiences from the Urban Waste Expertise Program; WASTE: Gouda, The Netherlands, 2001; ISBN 9076639027. [Google Scholar]

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). Finding Data for Local Government Areas. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/Home/Finding+data+for+Local+Government+areas (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Beunen, R.; van Assche, K.; Duineveld, M. Evolutionary Governance Theory: Theory and Applications; Beunen, R., Van Assche, K., Duineveld, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9783319122748. [Google Scholar]

- Hettne, B. Beyond the ‘new’ regionalism. New Polit. Econ. 2005, 10, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Prokopy, L. The Role of Sense of Place in Collaborative Planning. J. Sustain. Educ. 2016, 11, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lintz, G. A Conceptual Framework for Analysing Inter-municipal Cooperation on the Environment. Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Pluto Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bettache, K.; Chiu, C.Y. The Invisible Hand is an Ideology: Toward a Social Psychology of Neoliberalism. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, D.; Konings, M.; Cooper, M.; Primrose, D. The SAGE Handbook of Neoliberalism; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, C. The New Public Management: An Overview of Its Current Status. Adm. Si Manag. Public 2007, 8, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen, T.; Falk, A.; Huffman, D.; Sunde, U. Homo reciprocans: Survey evidence of behavioural outcomes. Econ. J. 2009, 119, 592–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowles, S.; Gintis, H. Homo reciprocans. Nature 2002, 415, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monbiot, G. Neoliberalism–The Ideology at the Root. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/15/neoliberalism-ideology-problem-george-monbiot (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Barter, N.; Bebbington, J. Environmental paradigms and organisations with an environmental mission. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 120–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beunen, R.; Van Assche, K. Steering in governance: Evolutionary perspectives. Polit. Gov. 2021, 9, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, K.; Beunen, R.; Duineveld, M. Evolutionary Governance Theory: An Introduction; Springer Science & Business Media: Cham, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Target | Action | Action Description 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Target 1 | Action 1.3 | The development of new markets for recycled products and materials in the region. |

| Action 1.9 | New regulations in the region to prevent the landfilling of recyclable materials. | |

| Target 2 | Action 2.5 | The delivery of targeted programs in the region to build businesses’ capability to identify and act on opportunities to avoid waste and increase materials’ efficiency and recovery. |

| Action 2.7 | Support community-based reuse and repair centres in the region, enabling communities to avoid creating waste. | |

| Action 2.12 | Support circular economy principles in the region’s urban planning, infrastructure and development projects. | |

| Action 2.15 | Undertake research to better understand the contributing factors to contamination in kerbside recycling bins, to inform future interventions. | |

| Target 3 | Action 3.16 | Explore opportunities to leverage existing regional development programs to support better waste management and resource recovery. |

| Action 3.17 | Increase access to waste and resource recovery infrastructure for regional, remote and Indigenous communities. | |

| Target 4 | Action 4.1 | Actions to increase the amount of recycled content used in road construction in the region. |

| Action 4.3 | Work with industry to increase the uptake of recycled content in other government infrastructure and building projects with priority given to plastics, glass and rubber. | |

| Action 4.7 | Supporting or promoting the region’s businesses that are applying circular economy practices, such as by running a recognition scheme or awards program. | |

| Target 5 | Action 5.9 | Better manage the import, export, use, manufacture and end-of-life disposal of products and articles containing hazardous substances. |

| Target 6 | Action 6.3 | Provide support to develop distributed infrastructure solutions to process organic waste, including composting infrastructure. |

| Action 6.4 | Delivering a FOGO (Food Organics and Garden Organics) service to a region or parts of it. | |

| Target 7 | Action 7.2 | Efforts to adjust a region’s waste data and reporting practices to support harmonisation with Australian Government practices and other jurisdictions. |

| Impulse | Pro-Regional Factors | Anti-Regional Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Resource | Shared resources (e.g., streams, air) | Natural barriers within the region (e.g., rivers, mountains) |

| Macro-economic | Common mode of production (e.g., industrial or agricultural) | Mixed modes of production |

| Centrality | High central-city dominance; High centre-periphery interdependence | Low central-city dominance; Low centre-periphery interdependence |

| Growth | Common growth and development experiences | Uneven growth and development experiences |

| Social | Similar cross-jurisdiction socioeconomic status | Dissimilar cross-jurisdiction socioeconomic status |

| Fiscal | Similar cross-jurisdiction fiscal capacity; Potential for economies of scale; Fiscal exploitation (for the exploited party) | Dissimilar cross-jurisdiction fiscal capacity; Fiscal exploitation (for exploiting party) |

| Equity | Support for redistribution | Resistance to redistribution |

| Political | Common political affiliation; Desire for a united front | Mixed political affiliations; Geographically concentrated minority groups |

| Legal | State and federal incentives favouring regionalisation | State and federal incentives constraining regionalisation |

| Historical | History of inter-jurisdictional cooperation and successful regional efforts | History of inter-jurisdictional antagonism and failed regional efforts; Long-standing local political borders |

| Dimensions/Types of Cooperation | Indirect | Transactional | Collaborative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of interaction | Knowledge exchange | Buying/Selling | Shared management |

| Commitment | Uncommitted | Contractual | Partnership |

| Governance complexity | Low | Middle | High |

| Representation | Unclear | Managers | Elected officials |

| Degree of institutionalisation | Informal | Formal | Formal |

| Type of interaction | Knowledge exchange | Buying/Selling | Shared management |

| Paradigm/Key Elements | Traditional Public Administration (TPA) | New Public Management (NPM) | New Public Governance (NPG) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paradigm peak | 1800s to 1970s | 1980s to today (fading) | 2000s to today (rising) |

| Theoretical roots | Political science and public policy | Neoliberalism, economics (esp. public choice theory), and management studies | Organisational sociology and network theory |

| Nature of the State | Unitary | Disaggregated | Plural and pluralist |

| Focus | How policy is made | Intra-organisational management | Inter-organisational governance |

| Governance mechanism | Hierarchy | Market through traditional contracts | Trust or relational contracts |

| Value base | Public sector ethos | Competition in market context | Neo-corporatist |

| Theoretical Component 1 | Aspect of Inquiry | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Macro-level structures | IMC-WM partnerships |

|

| Micro-institutional factors | Internal relations | Engagement dynamic indicators:

|

| Institutional output | Joint waste management activities |

|

| Integration Mechanism | Prevalence and Description |

|---|---|

| Urban waste authorities | This integration mechanism refers to a statutory approach whereby a regional subsidiary is established under the Local Government Act of the relevant state to deliver waste management services for a group of member councils who have chosen to co-produce services via the new statutory entity. Typically, governance and oversight are performed by a Board comprised either primarily or entirely of councillors from each member council. Executives and council officers from the member councils work together in various capacities including performing as a governance support mechanism to the board, or through networks of professionals collaborating on particular program areas. The Urban waste authority approach to IMC-WM is currently only active in WA (contexts: Metropolitan, some Inner Regional) and SA (contexts: Metropolitan, some Inner Regional). In WA, they are known as ‘Regional Councils’ and, less often, ‘Regional Local Governments’, and they are established under Part 3, Division 4 of the Local Government Act 1995 (WA). While Regional Councils can be developed for any specified purpose, waste management is by far the most common reason they are established. In SA, the Urban waste authority approach to IMC-WM is known as a ‘Waste Management Authority’ and is established under Section 4.3 of the Local Government Act 1999 (SA). In both SA and WA, establishing this type of IMC-WM partnership requires approval by the relevant minister. While the Urban waste authority mechanism type primarily exists in metropolitan contexts, they are also found in some Inner Regional (see Figure 3) designations such as WA’s Bunbury-Harvey region and SA’s Fleurieu and Adelaide Hills regions. |

| Waste sub-groups within regional associations | This integration mechanism refers to an IMC-WM partnership that emerges within and continues to be hosted by a broader regional association. These host organisations are most commonly known as ‘Regional Organisations of Councils’ (ROCs). Other terms used are ‘Council of Mayors’ in Queensland, ‘Joint Authorities’ in NSW and ‘Local Governments Associations’ or simply ‘groups’ in SA. This type is identified as most active in NSW (contexts: mainly Metropolitan, Inner Regional and Outer Regional), SA (contexts: mainly Outer Regional, some Remote, some Inner Regional), regional WA (contexts: mainly Inner Regional and Remote) and regional QLD (all regional contexts). While identified as active in the above areas, any area with a regional association has the capacity to quickly form a waste sub-group of the member councils involved in the association as a means to address emergent issues or exploit new opportunities for the already defined region. In some cases, waste sub-groups transition into becoming their own autonomous organisations that are associated with, but no longer embedded within, their inaugurating regional association. |

| Autonomous regional waste groups and Investment oriented alliances | This type is known by various names such as ‘regional waste group’, ‘waste alliance’ and ‘waste management working group’. As a mechanism which can be established ad hoc, any group of councils can opt to begin collaborating autonomously and without statutory decree. Governance arrangements are derived from a Memorandum of Understanding, Terms of Reference or some other agreement. Councils open to investing in new shared infrastructure together are also seen to engage via similar voluntary alliances oriented around undertaking EOI (Expression of Interest) and tendering processes together. Identified as active in regional NSW (contexts: mainly Inner Regional, Outer Regional and some Remote); regional NT (contexts: mainly Very Remote); regional WA (contexts: Inner Regional and Outer Regional); south-east QLD (contexts: Metropolitan and Inner Regional) and Tasmania (contexts: mainly Outer Regional). |

| State-led waste and resource recovery groups | Known as waste and resource recovery groups (WRRGs), this type is only present in Victoria (as of 2021). While Victoria’s WRRGs are ‘portfolio agencies’ of the state government, these institutions operate under a social license that is fortified through the significant levels of inter-municipal cooperation they facilitate between the constituent councils. For example, the constituent councils are typically allocated a set allocation of board members, and member councils’ delegates engage through ‘Local Government Forums’, technical advisory groups and other specialist networks within the WRRG. This type of IMC-WM is the only integration mechanism in Australia that falls within Feiock’s concept of ‘Imposed Authority’ [39]. |

| Macro-regional advisory mechanisms | This mechanism refers to networks of councils working together voluntarily on MSW policy on a larger, macro-regional scale. These arrangements can act as ‘networks of networks’ in that they can comprise members which are themselves IMC-WM partnerships or include associate memberships from industry groups. Macro-regional advisory mechanisms should be considered distinct from the other integration mechanisms featured in this taxonomy in that they are less oriented around joint delivery of programs, and usually more focused on networking and creating an institution for advisory engagement that can deliver a pluralist voice on MSW policy matters, especially to higher tiers of government. Examples include the Local Authority Waste Management Advisory Council (LAWMAC) in North Queensland, the Municipal Waste Advisory Council in Perth (WA) and the statewide Renew NSW network throughout NSW. This type of cooperation is often facilitated by the local government association of the state, by a state government subsidiary body or through a regional alliance. The presence of ‘Macro-level advisory mechanisms’ was identified through responses from the IMC-WM partnerships who participate in them, rather than their direct participation in the IMC-WM Census. As this particular type of IMC-WM mechanism operates in such a distinct manner to the other types, it is included in the taxonomy but not included in any of the other analyses throughout this paper. |

| Type of Engagement | Number of Partnerships Engaged | Overall % of Responding Partnerships |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-boundary Governance Meeting/Forum | 34 | 97% |

| Cross-boundary Waste Education Group | 12 | 34% |

| Cross-boundary Technical Advisory Group | 11 | 31% |

| Cross-boundary—Other reported meetings | 15 | 42% |

| Shared Waste Program Activity | Total | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Reactive engagement (e.g., submissions) to state govt on waste policy | 27 | 77% |

| 2. Recycling and contamination campaigns | 24 | 69% |

| 3. Social media engagement about the region’s waste initiatives | 22 | 63% |

| 4. Proactive lobbying as a region to state and federal govts on waste policy | 22 | 63% |

| 5. Publishing a regional waste strategy | 20 | 57% |

| 6. Food waste behaviour campaigns | 18 | 51% |

| 7. Reuse/upcycling/repair campaigns | 18 | 51% |

| 8. Littering campaigns | 17 | 49% |

| 9. Production of collateral (e.g., recycling fridge magnets) | 17 | 49% |

| 10. Reactive engagement (e.g., submissions) to federal govt on waste policy | 17 | 49% |

| 11. Networking events between waste professionals | 14 | 40% |

| 12. Hosting regional waste conferences or community/industry forums | 14 | 40% |

| 13. Delivering a school education program | 13 | 37% |

| 14. Engagement with Indigenous communities | 11 | 31% |

| 15. Business recycling campaigns | 10 | 29% |

| Partnership Code | State | Legislative Mechanism | Regional Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| D | NSW | Voluntary grouping | 100% Inner Regional |

| G | VIC | Statutory organisation | 50% Inner Regional, 50% Outer Regional |

| H | NSW | Voluntary grouping | 10% Inner Regional, 40% Outer Regional, 40% Remote, 10% Very Remote |

| I | QLD | Voluntary grouping | 40% Outer Regional, 30% Remote, 30% Very Remote |

| J | NSW | Statutory organisation | 100% Major city |

| K | TAS | Statutory organisation | 50% Inner Regional, 50% Outer Regional |

| O | VIC | Statutory organisation | 100% Outer Regional |

| Q | VIC | Statutory organisation | 40% Inner Regional, 60% Outer Regional |

| CC | WA | Statutory organisation | 100% Major city |

| GG | NSW | Voluntary grouping | 10% Major city, 60% Inner Regional, 30% Outer Regional |

| II | VIC | Statutory organisation | 100% Major city |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tobin, S.; Zaman, A. Regional Cooperation in Waste Management: Examining Australia’s Experience with Inter-municipal Cooperative Partnerships. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031578

Tobin S, Zaman A. Regional Cooperation in Waste Management: Examining Australia’s Experience with Inter-municipal Cooperative Partnerships. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031578

Chicago/Turabian StyleTobin, Steven, and Atiq Zaman. 2022. "Regional Cooperation in Waste Management: Examining Australia’s Experience with Inter-municipal Cooperative Partnerships" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031578

APA StyleTobin, S., & Zaman, A. (2022). Regional Cooperation in Waste Management: Examining Australia’s Experience with Inter-municipal Cooperative Partnerships. Sustainability, 14(3), 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031578