Subjective Social Class and the Retention Intentions of Teachers from the Publicly Funded Normal Students Program in China: The Dual Mediating Effect of Organizational and Professional Identity

Abstract

1. Introduction

Subjective Social Class and the Retention Intentions of Rural Teachers

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Variable Descriptions

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Common Method Bias Test

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Relevant Analysis

3.3. GSEM Results Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Approval

References

- Xue, E.; Li, J.; Li, X. Sustainable Development of Education in Rural Areas for Rural Revitalization in China: A Comprehensive Policy Circle Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 13, 13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Realistic dilemma and strategic choice of sustainable development of rural education in the new urbanization process. J. Southwest Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 41, 98–105+191. [Google Scholar]

- Guangming Daily. How to Improve the Selection and Withdrawal of Publicly Funded Teacher Trainees. Available online: https://edu.gmw.cn/2020-10/29/content_34320666.htm (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Su, S.F.; Huang, L.F. Guided return: The functional logic of the evolution of local publicly funded normal student policy—An analysis based on the texts of local publicly funded normal student policies in 30 provinces. Educ. Res. 2021, 42, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.S.; Shi, H. Survey on the willingness of publicly funded teacher trainees from local teacher training colleges to teach in rural elementary school. Educ. Res. Exp. 2019, 6, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Daily. Strongly Supporting the World’s Largest Education System. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s5147/202011/t20201127_501966.html (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Fu, W.D.; Fu, Y.Z. An empirical study on the factors influencing the employment of the first free teacher training graduates--a survey based on six national ministerial teacher training universities. Fudan Educ. Forum 2012, 10, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, T.Z. The effects of selection methods and school retention strategies on urban and rural teachers’ willingness to stay—A questionnaire survey based on 16,787 primary and secondary school teachers in five provinces in central and western China. J. Educ. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 2021, 20, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.Q.; Chen, X.M. Analysis of Teacher Training Students’ Willingness to Teach in Rural Areas and the Influencing Factors in the Context of the Implementation of the Rural Teacher Living Subsidy Policy—A Survey Based on 15 Colleges and Universities in Poor Western Areas. Teach. Educ. Res. 2019, 31, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Fang, X. Willingness of “post-00” teacher trainees to teach in rural areas and policy improvement. Contemp. Youth Stud. 2021, 3, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, M.W.; Tan, J.J.X.; Tannenbaum, M.B. The social ladder: A rank-based perspective on social class. Psychol. Inq. 2013, 24, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loignon, A.C.; Kodydek, G. The effects of objective and subjective social class on leadership emergence. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 59, 1162–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.Z.; Bai, Z.W. A study on the subjective social status of secondary school teachers in China and its influencing factors. Tsinghua Univ. Educ. Res. 2021, 42, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Jackman, M.R.; Jackman, R.W. An interpretation of the relation between objective and subjective social status. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1973, 38, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, M.W.; PIiff, P.K.; Keltner, D. Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, N.E.; Epel, E.S.; Castellazzo, G.; Ickovics, J.R. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2000, 19, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.S.; Fan, H.G. Class self-positioning, income inequality, and subjective mobility perceptions (2003–2013). Chin. Soc. Sci. 2016, 12, 109–126, 206–207. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. The Theory of Social Division of Labor; Di, Y.M., Translator; The Commercial Press: Shanghai, China, 1995; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; p. 331. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.L. Social Conflict and Class Consciousness: A Study of Social Contradictions in Contemporary China. Society 2005, 1, 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Relative deprivation status and class perception. Sociol. Res. 2002, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. Why Status Hierarchy Identity Shifts Downward and the Transformation of the Basis of Status Hierarchy Identity. Society 2013, 33, 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, M.W.; Piff, P.K.; Mendoza, D.; Rheinschmidt, M.L.; Keltner, D. Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 119, 546–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.Q.; Wei, H.M. A review of research on the impact of social class in organizations. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 3, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Côté, S. How social class shapes thoughts and actions in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2011, 31, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loignon, A.C.; Woehr, D.J. Social class in the organizational sciences: A conceptual integration and meta-analytic review. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Park, E.C. The impact of differences between subjective and objective social class on life satisfaction among the korean population in early old age: Analysis of Korean longitudinal study on aging. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 67, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.; Smeaton, D. Older British employees’ declining attitudes over 20 years and across classes. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 1619–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.J.X.; Kraus, M.W.; Carpenter, N.C.; Adler, N.E. The association between objective and subjective socioeconomic status and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 970–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, C.J.; Brown, G.D.A.; Moore, S.C. Money and Happiness: Rank of Income, Not Income, Affects Life Satisfaction. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, A. Mental Health in Upper Class Communities: The Relationship between Subjective Social Class, Help-Seeking Behaviors, and Treatment Barriers. Dissertation Thesis, Adler School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.F.; Jing, H.H.; Chen, B. The effect of subjective social class on subjective well-being: The role of security and social support. J. Southwest. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 45, 106–112, 190–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ruckdeschel, D.E.; Egbert, D. Objective and Subjective Social Class, Locus of Control, and Global Self-Worth in Predicting Dropout. Dissertations Thesis, Gradworks, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.X. The social mentality of different subjective social classes. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2018, 1, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Geng, X.W. The influence of organizational political perception on rural teachers’ intention to leave: The mediating role of organizational equity and organizational identity. Psychol. Behav. Res. 2018, 16, 678–683. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, W.W.; Chen, C.J.; Sun, D. A study on the influential mechanism of kindergarten teachers’ tendency to leave their jobs-based on a mediated model with moderation. Educ. Dev. Res. 2020, 40, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, L.M.; Porck, J.P.; Walter, S.L.; Scrimpshire, A.J.; Zabinski, A.M. A meta-analytic review of identi-fication at work: Relative contribution of team, organizational, and professional identification. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 107, 795–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowska, L. Identity as a narrative of autobiography. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2010, 1, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, L. Research on the Mechanism of Organizational Identity and Employee Turnover Intention. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Social Science and Higher Education (ICSSHE 2019), Xiamen, China, 23–25 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bruch, C.H. Organizational identity strength, identification, and commitment and their relationships to turnover intention: Does organizational hierarchy matter? J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 27, 585–605. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.X.; Li, Y.M.; Zhang, N.; Shen, J.L. The relationship between organizational justice, organizational identity and teachers’ intention to leave. Psychol. Behav. Res. 2009, 7, 253–257+283. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, S.; Kovacs, B. Reviewer social class influences responses to online evaluations of an organization. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.J.; Fu, X.J. The effect of altruistic motivation on knowledge sharing among elementary and middle school teachers—The moderating role of organizational identity and organizational support perceptions. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Hekman, D.R.; Steensma, H.K.; Bigley, G.A.; Hereford, J.F. Effects of organizational and professional identification on the relationship between administrators’ social influence and professional employees’ adoption of new work behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G.; Rockmann, K.W.; Kaufmann, J.B. Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles i the customization of identity among medical residents. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wang, E.; Si, J.; Sui, X.; Yi, Z.; Zheng, Z. Professional identity and turnover intention amongst Chinese social workers: Roles of job burnout and a social work degree. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2021, 52, bcab155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. The correlation between preschool teachers’ professional identity and turnover intention. Adv. Educ. 2019, 9, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.; Hofman, J.E. Professional identity in institutions of higher learning in Israel. High. Educ. 1988, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.H.; Song, G.W.; Zhang, D.J. The structure and scale of professional identity of primary and secondary school teachers in China. Teach. Educ. Res. 2013, 25, 55–60+75. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.J. A study of social workers’ professional identity and tendency to leave the profession—Based on a survey of social workers in Shenzhen. J. Humanit. 2017, 6, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Jin, Z.F.; Ge, L. Why the teaching profession is more attractive to women—A perspective based on social comparison theory. Educ. Dev. Res. 2020, 40, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney, G.; Tompkins, P.K. Coming to terms with organizational identification and Commitment. Cent. States Speech J. 1987, 38, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.P.; Li, M.Y.; Wang, S.Q. The relationship between social support and kindergarten teachers’ intention to stay in their jobs: The serial mediating effect of organizational equity and work commitment. Presch. Educ. Res. 2021, 2, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Jiang, F. Research on factors influencing teachers’ willingness to participate in the context of “Silver Age Lectures”—Analysis based on multi-cluster structural equation model. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020, 32, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Research on the trend of social class structure changes in China—An analysis based on national CGSS survey data. Res. Social. Chin. Charact. 2011, 3, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.Z.; Lu, S.; Jin, Z.F. The reform of primary and secondary school teachers’ titles in China: Development history, key issues and policy suggestions. J. Chin. Educ. 2017, 12, 66–72+78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Xu, J.B. The relationship between subjective status identity and transfer intention of county compulsory education teachers: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Mod. Educ. Manag. 2018, 2, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.M.; Liu, F. Free teacher training students’ education policy. J. Hangzhou Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2008, 30, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Zhu, F.; Liu, L. Person–organization fit and turnover intention: Professional identity as a moderator. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2016, 44, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.G. The professional identity of school counsellors in east and southeast Asia. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2022, 22, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwalibóg, E. Personality, temperament, organizational climate and organizational citizenship behavior of volunteers. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2011, 2, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Yang, W.J.; Shen, J.L. The relationship between teachers’ organizational identity, job satisfaction and affective commitment. Psychol. Behav. Res. 2011, 9, 185–189+208. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Jiang, S. Mechanisms from person–environment fit to professional identity of social workers in china: The roles of person-organization value congruence and collective psychological ownership. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2022, 48, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.H. The dilemma and the way out of the identity of free teacher training students. Educ. Theory Pract. 2016, 36, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Categories | Number | Ratio% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 271 | 18.1 |

| Female | 1227 | 81.9 | |

| Marriage | Unmarried | 105 | 7.0 |

| Married | 1327 | 88.6 | |

| Bereaved spouse | 3 | 0.2 | |

| Divorced/separated | 49 | 3.9 | |

| Others | 4 | 0.3 | |

| Household | Rural | 502 | 33.5 |

| Urban | 996 | 66.5 | |

| Age | Under 30 years old | 165 | 11.0 |

| 30 years old and above | 1333 | 89.0 | |

| Political background | Communist Party of China | 249 | 16.6 |

| Democratic Party | 3 | 0.2 | |

| Non-partisan | 164 | 10.9 | |

| Communist Youth League | 289 | 19.3 | |

| The Crowd | 793 | 52.9 | |

| Title | No title | 75 | 5.0 |

| Title III teacher | 17 | 1.1 | |

| Title II teacher | 467 | 31.2 | |

| Title I teacher | 819 | 54.7 | |

| Senior teacher | 120 | 8.0 |

| Variables | Publicly Funded Normal Students Program | Public Recruitment | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | ||

| Retention intentions | 0.371 | 0.013 | 0.413 | 0.006 | 0.002 |

| Subjective social class | 3.475 | 0.055 | 4.048 | 0.023 | 0.000 |

| Organizational Identity | 3.666 | 0.468 | 3.608 | 0.475 | 0.000 |

| Professional identity | 3.524 | 0.530 | 3.562 | 0.519 | 0.000 |

| Code | Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Retention intentions | 1 | |||

| 2 | Subjective social class | 0.208 *** | 1 | ||

| 3 | Organizational Identity | 0.387 *** | 0.174 *** | 1 | |

| 4 | Professional identity | 0.414 *** | 0.281 *** | 0.704 *** | 1 |

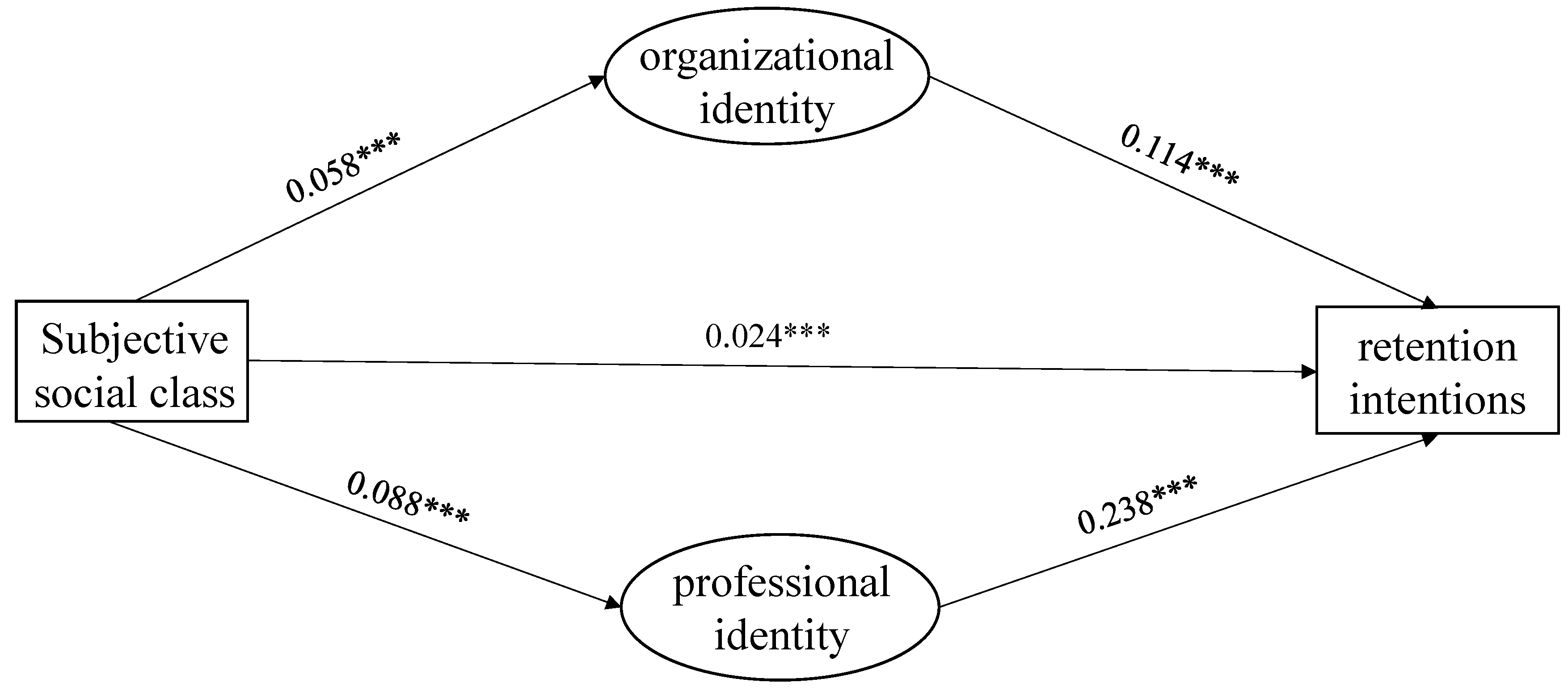

| β | S.E. | Z | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retention intentions | |||

| Subjective social class | 0.024 *** | 0.006 | 4.066 |

| Organizational Identity | 0.114 *** | 0.032 | 3.648 |

| Professional identity | 0.238 *** | 0.040 | 5.940 |

| Gender | −0.078 ** | 0.030 | −2.666 |

| Title | −0.039 * | 0.017 | −2.006 |

| School location | 0.138 *** | 0.027 | 5.290 |

| Organizational Identity | |||

| Subjective social class | 0.058 *** | 0.008 | 6.808 |

| Professional identity | |||

| Subjective social class | 0.088 *** | 0.008 | 11.218 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Fu, W. Subjective Social Class and the Retention Intentions of Teachers from the Publicly Funded Normal Students Program in China: The Dual Mediating Effect of Organizational and Professional Identity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316241

Li T, Zhang L, Fu W. Subjective Social Class and the Retention Intentions of Teachers from the Publicly Funded Normal Students Program in China: The Dual Mediating Effect of Organizational and Professional Identity. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):16241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316241

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Tingzhou, Luo Zhang, and Wangqian Fu. 2022. "Subjective Social Class and the Retention Intentions of Teachers from the Publicly Funded Normal Students Program in China: The Dual Mediating Effect of Organizational and Professional Identity" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 16241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316241

APA StyleLi, T., Zhang, L., & Fu, W. (2022). Subjective Social Class and the Retention Intentions of Teachers from the Publicly Funded Normal Students Program in China: The Dual Mediating Effect of Organizational and Professional Identity. Sustainability, 14(23), 16241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316241