The Contribution of Environmental and Cultural Aspects of Pastoralism in the Provision of Ecosystem Services: The Case of the Silesian Beskid Mts (Southern Poland)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Studies

2.3. Cultural Studies

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

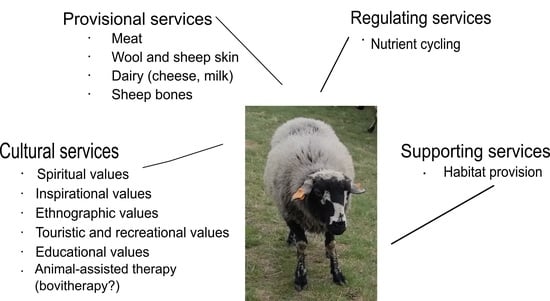

3.1. Provisional Services

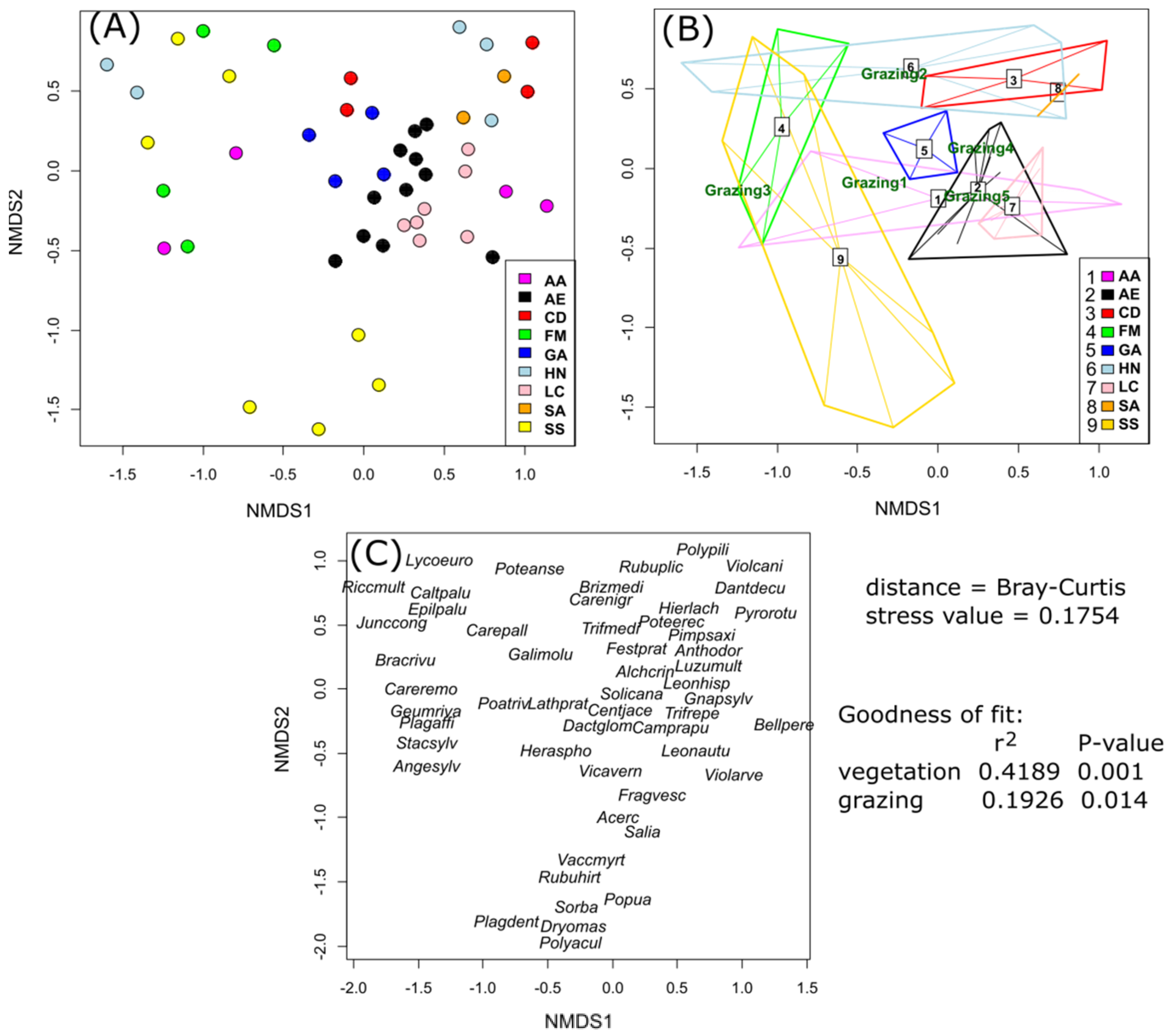

3.2. Regulating and Supporting Services

3.3. Cultural Services

- Communal sheep herding takes place on pastures belonging to many landowners;

- Sheep do not belong to the head shepherd, but to gazdas (sheep owners) who gave their sheep into the head shepherd’s care for the summer;

- A head shepherd, while sheltering, conducts milk processing, produces various types of cheese, e.g., bundz, oscypki, redykołki, bryndza, Vlach cheese, and sells these products;

- The head shepherd is responsible for the herd, the wellbeing of sheep and their milking, as well as for the accounting and negotiations with sheep owners and pasture owners.

4. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sayre, N.F.; Davis, D.K.; Bestelmeyer, B.; Williamson, J.C. Rangelands: Where anthromes meet their limits. Land 2017, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, M.A.; Kuhn, N.J.; Fikre, T.Z. The role of pastoralism in regulating ecosystem services. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2016, 35, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asner, G.P.; Elmore, A.J.; Olander, L.P.; Martin, R.E.; Harris, A.T. Grazing systems, ecosystem responses, and global change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2004, 29, 261–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, K.A.; Reid, R.S.; Behnke, R.H., Jr.; Hobbs, N.T. Fragmentation in Semi-Arid and Arid Landscapes; Consequences for human and natural systems; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, L.; Havstad, K.M.; Peters, D.P.C.; Skaggs, R.; Brown, J.; Bestelmeyer, B.; Herrick, J. Ecological services to and from rangelands of the United States. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 64, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- McGahey, D.; Davies, J.; Hagelberg, N.; Ouedraogo, R. Pastoralism and the Green Economy: A Natural Nexus? International Union for Conservation of Nature, Gland, Switzerland/United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014; p. 58. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2014-034.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Leroy, G.; Hoffmann, I.; From, T.; Hiemstra, S.J.; Gandini, G. Perception of livestock ecosystem services in grazing areas. Animal 2018, 12, 2627–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, M.; Nicolas, G.; Cinardi, G.; Van Boeckel, T.P.; Vanwambeke, S.O.; Wint, G.R.; Robinson, T.P. Global distribution data for cattle, buffaloes, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens and ducks in 2010. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsoner, T.; Vigl, L.E.; Manck, F.; Jaritz, G.; Tappeiner, U.; Tasser, E. Indigenous livestock breeds as indicators for cultural ecosystem services: A spatial analysis within the Alpine Space. Ecol. Ind. 2018, 94, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benthien, O.; Braun, M.; Riemann, J.C.; Stolter, C. Long-term effect of sheep and goat grazing on plant diversity in a semi-natural dry grassland habitat. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszecki, T.M.; Warda, M.; Kulik, M.; Junkuszew, A.; Patkowski, K.; Bojar, W.; Krupinski, J. Wypas owiec sposobem ochrony różnorodności zbiorowisk roślinnych w cennych przyrodniczo siedliskach. Wiad. Zootech. 2017, 55, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Salachna, A.; Kobiela-Mendrek, K.; Kohut, M.; Rom, M.; Broda, J. The Pastoralism in the Silesian Beskids (South Poland): In the Past and Today. In Sheep Farming-Herds Husbandry, Management System, Reproduction and Improvement of Animal Health; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czamańska, I. The Vlachs–Several Research Problems. Balc. Posnaniensia Acta Studia 2015, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jawor, G. Ethnic Aspects of Settlement in IusValachicum in Medieval Poland (from the 14th to the beginning of the 16th century). Balc. Posnaniensia Acta Studia 2015, 22, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondracki, J. Physical Geography of Poland; PWN Publishing: Warsaw, Poland, 1980; pp. 1–463, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Durło, G. Climate of Silesian Beskid; Drukrol Publishing: Cracow, Poland, 2012; p. 221, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Wiszniewski, W.; Chełchowski, W. The Climate Characteristic and Climate-Forestry Regionalization of Poland; WKiŁ Publishing: Warsaw, Poland, 1975; p. 36, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Okołowicz, W.; Martyn, D. Climatic regions in Poland. In Geographical Atlas; PPWK Publisher: Warsaw, Poland, 1979; p. 11, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Durło, G. The Impact of Observed and Predicted Climate Conditions on the Stability of Mountain Forest Stands in the Silesian Beskid; Agricultural University in Cracow Publishing: Cracow, Poland, 2012; p. 163, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Sobala, M.; Rahmonov, O. The human impact on changes in the forest range of the Silesian Beskids (Western Carpathians). Resources 2020, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broda, J.; Paczkowska, E. Surface morphology and physical properties of sheep wool of selected Polish breeds. PJMEE 2021, 1, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie, Grund-Züge der Vegetationskunde; 3 Aufl. (Phytosociology, the basis of vegetation science, Vol. 3); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1964; p. 865. [Google Scholar]

- Marcol, K. Kształtowanie pamięci o pasterskim dziedzictwie górali beskidzkich. Národop. Věstn. 2019, 2, 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Marcol, K.; Kurcz, M. Continuities and Disruptions in Transhumance Practices in the Silesian Beskids (Poland): The Case of Koniaków Village. In Grazing Communities: Pastoralism on the Move and Biocultural Heritage Frictions; Bindi, L., Ed.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 174–202. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Azeem, M.; Ali, A.; Jeyasundar, P.G.A.; Bashir, S.; Hussain, Q.; Wahid, F.; Ali, E.F.; Abdelrahman, H.; Li, R.; Antoniadis, V.; et al. Effects of sheep bone biochar on soil quality, maize growth, and fractionation and phytoavailability of Cd and Zn in a mining-contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbary Aslani, F.; Hukins, D.W.; Shepherd, D.E. Applicability of sheep and pig models for cancellous bone in human vertebral bodies. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 2012, 226, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuss, K.M.; Auer, J.A.; Boos, A.; Rechenberg, B.V. An animal model in sheep for biocompatibility testing of biomaterials in cancellous bones. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2006, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocój, E. Powroty do tematów pasterskich. Zwyczaje i wierzenia związane z rozpoczęciem sezonu pasterskiego na pograniczu polsko-słowackim w XXI wieku. Etnogr. Pol. 2018, 62, 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Spyra, J. Wisła. Dzieje Beskidzkiej Wsi do 1918 Roku. Monografia Wisły; Urząd Miasta w Wiśle: Wisła, Poland, 2007; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kiereś, M. O gospodarce sałaszniczo-pasterskiej w etnograficznej pigułce. In Owce w Beskidach, Czyli Owca Plus po Góralsku; Michałek, J., Ed.; Śląskie-Pozytywna Energia: Istebna, Poland, 2010; pp. 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kiereś, M. Beskidzkie sałasznictwo na przestrzeni wieków w świetle badań archiwalnych i terenowych. In Beskidzkie Sałasznictwo na Przestrzeni Wieków; Fundacja Pasterstwo Transhumancyjne: Istebna, Poland, 2019; pp. 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Štika, J. O sałaszach, gospodarstwie sałaszniczym i sałaszniczych obyczajach. In Owce w Beskidach, czyli Owca Plus po Góralsku; Financed from the budget of the Silesian, Voivodeship; Michałek, J., Ed.; commune Istebna: Istebna, Poland, 2010; pp. 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, L.; Szymik, J. (Eds.) Sałasznictwo w Beskidach; Sekcja Ludoznawcza ZG PZKO: Czeski Cieszyn, Czech Republic, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Michałek, J. Współczesne sałasznictwo–Co to takiego? In Bacowie i Wałasi. Kultura Pasterska na Pograniczu Polsko-Słowackim; Kocój, E., Michałek, J., Eds.; Delta Partner: Cieszyn, Poland, 2018; pp. 172–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kohut, P.; Gąsienica-Makowski, A. Dziewięć sił Karpackich; Centrum UNEP/GRID: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kopoczek, A. Instrumenty Muzyczne Beskidu Śląskiego i Żywieckiego; Beskidzka Oficyna Wydawnicza: Bielsko-Biała, Poland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Oczko, A. Pasterska wspólnota językowa. In Bacowie i Wałasi. Kultura Pasterska na Pograniczu Polsko-Słowackim; Kocój, E., Michałek, J., Eds.; Delta Partners: Cieszyn, Poland, 2018; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Czerwińska, K. W poszukiwaniu utraconej symbiozy, Rzecz o relacji dizajnu i natury. In Ekologia Kulturowa. Perspektywy i Interpretacje; Czerwińska, K., Drożdż, A., Dzięgiel, M., Kujawska, M., Kurcz, M., Łuczaj, Ł., Marcol, K., Odoj, M.S.G., Eds.; Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2016; pp. 142–162. [Google Scholar]

- Corscadden, K.W.; Biggs, J.N.; Stiles, D.K. Sheep’s wool insulation: A sustainable alternative use for a renewable resource? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 86, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, Z. Fitosocjologiczne Uwarunkowa-nia Ochrony Przyrody Beskidu Śląskiego (Karpa-ty Zachodnie); Prace Naukowe UŚ, 2418; University of Silesia: Katowice, Poland, 2006; p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Wilczek, Z.; Wytyczak, K.; Zarzycka, M. Walory szaty roślinnej jako podstawa powołania nowych form ochrony przyrody w masywie Ochodzitej (Beskid Śląski). Acta Geogr. Sil. 2019, 13, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Perzanowska, J. Bogate florystycznie górskie i niżowe murawy bliźniczkowe (Nardetalia–płaty bogate florystycznie). In Poradnik Ochrony Siedlisk i Gatunków Natura 2000–Podręcznik Metodyczny. T. 3. Wyd; Herbich, J., Ed.; Ministerstwo Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 2004; pp. 140–158. [Google Scholar]

- Czaplicki, Z.; Ruszkowski, K. Sheep farming in Poland–collapse or temporary setback. Prz. Włók. 2007, 61, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Węglarzy, K.; Skrzyżala, I.; Pellar, A. “OWCA PLUS” programme for cultivating sheep farming tradition in the Cieszyn Land. Wiad. Zootech. 2011, 49, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Niżnikowski, R.; Strzelec, E. Sheep and wool production in Central and Eastern Europe. In The 63rdEAAP Annual Meeting, Book of Abstracts; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2012; p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- Łach, J. The Valachian shepherd traditions of the Little Beskid as the basis for creating a linear product within the framework of cultural tourism. Tur. Kult. 2019, 4, 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kohut, P. W sprawach owczarskich zaczynam szukać własnej drogi. In Beskidzkie Sałasznictwo na Przestrzeni Wieków; Commune Istebna: Istebna, Poland, 2019; pp. 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Affek, A.N.; Kowalska, A. Ecosystem potentials to provide services in the view of direct users. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Ecosystem Services | Detailed Description |

|---|---|

| Provisional services |

|

| Regulating services |

|

| Supporting services |

|

| Type of Cultural Service in the Ecosystem | Detailed Description |

|---|---|

| Spiritual values |

|

| Inspirational values |

|

| Ethnographic values |

|

| Touristic and recreational values |

|

| Educational values |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salachna, A.; Marcol, K.; Broda, J.; Chmura, D. The Contribution of Environmental and Cultural Aspects of Pastoralism in the Provision of Ecosystem Services: The Case of the Silesian Beskid Mts (Southern Poland). Sustainability 2022, 14, 10020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610020

Salachna A, Marcol K, Broda J, Chmura D. The Contribution of Environmental and Cultural Aspects of Pastoralism in the Provision of Ecosystem Services: The Case of the Silesian Beskid Mts (Southern Poland). Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610020

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalachna, Anna, Katarzyna Marcol, Jan Broda, and Damian Chmura. 2022. "The Contribution of Environmental and Cultural Aspects of Pastoralism in the Provision of Ecosystem Services: The Case of the Silesian Beskid Mts (Southern Poland)" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610020

APA StyleSalachna, A., Marcol, K., Broda, J., & Chmura, D. (2022). The Contribution of Environmental and Cultural Aspects of Pastoralism in the Provision of Ecosystem Services: The Case of the Silesian Beskid Mts (Southern Poland). Sustainability, 14(16), 10020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610020