The Preference Analysis for Hikers’ Choice of Hiking Trail

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Routes making territories with rich natural conditions accessible;

- Areas rich in cultural and historical monuments;

- Routes of a few kilometres to several tens of kilometres, with the exception of several thousand kilometres-long trunk roads [9].

- Red colour—indicates long-distance and most important trails;

- Blue colour—more significant medium-length trails;

- Green colour—shorter trails of local importance;

- Yellow colour—the shortest sections, connecting trails, or shortcuts; they connect, for example, red with blue [54].

2. Materials and Methods

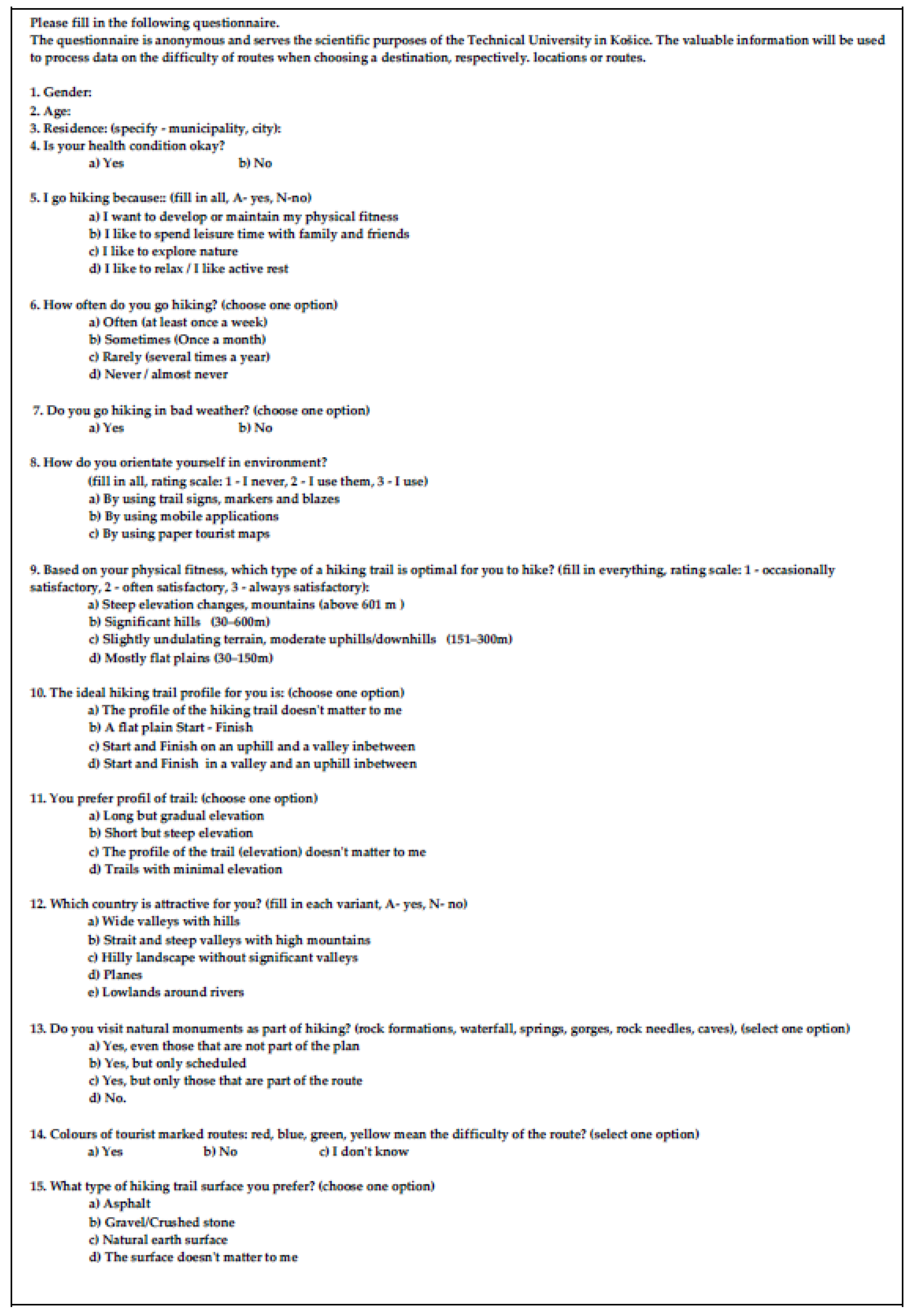

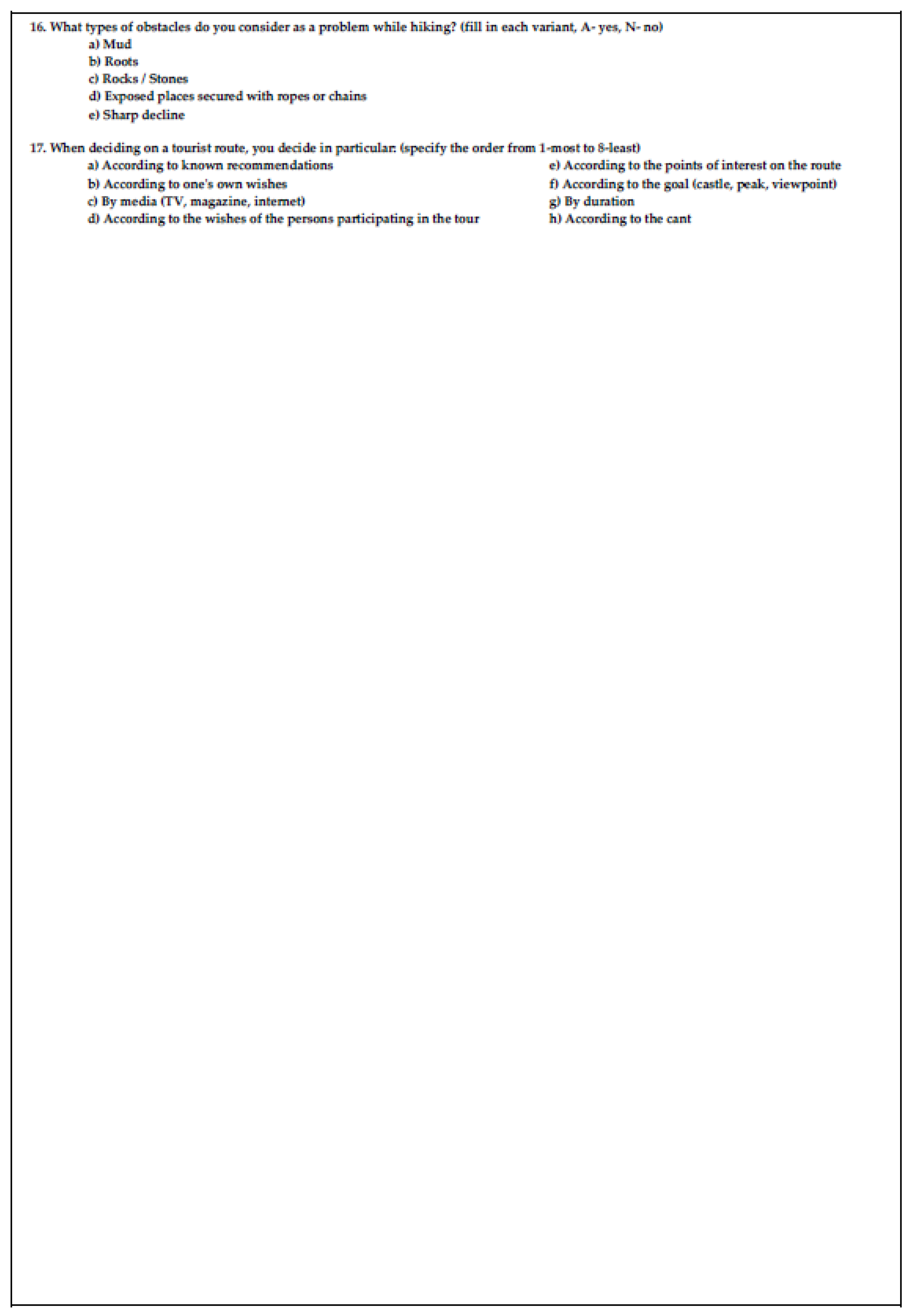

2.1. Public Opinion Survey (Questionnaire)

- Age, sex, place of residence.

- Why, in what weather, and how often they go for a hike, also on the basis of what they choose a hiking trail.

- Optimality in terms of their physical limits, terrain elevation, attractiveness of the environment, hiking trail surface, trail obstacles, and natural monuments.

- How hikers orientate themselves in the environment and how familiar they are with hiking trail markings.

- Group 1—teenagers (19 years and under);

- Group 2—younger working people (20–39 years);

- Group 3—older working people (40–59 years);

- Group 4—pensioners (60 years and older).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Duffková, J.; Urban, L.; Dubský, J. Sociologie Životního Stylu, 1st ed.; Vydavatelství a Nakladatelství Aleš Čeněk: Pilsen, Czech Republic, 2008; 237p, ISBN 978-80-7380-123-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sigmund, E.; Sigmundová, D. Pohybová Aktivita Pro Podporu Zdraví Dětí a Mládeže; Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2011; 176p, ISBN 9788024428116. [Google Scholar]

- Novotný, J. Hypokineze a “Civilizační Nemoci”. 2016. Available online: http://www.fsps.muni.cz/~novotny/Hypokin.htm (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.minzp.sk/files/oblasti/udrzatelny-rozvoj/sdgs-dokument-sk-verzia-final.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Marcus, B.H.; Forsyth, L.H. Psychologie Aktivního Spôsobu Života; Portál: Praha, Czech Republic, 2010; 224p, ISBN 978-80-7367-654-4. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/ (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Sekot, A. Pohybové Aktivity Pohledem Sociologie, 1st ed.; Masarykova Univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2015; 151p, ISBN 978-80-210-7918-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kalman, M.; Hamřík, Z.; Pavelka, J. Podpora Pohybové Aktivity pro Odbornou Veřejnost, 1st ed.; ORE—Institute: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2009; 172p, ISBN 978-80-254-5965-2. [Google Scholar]

- Matlovičová, K.; Klamár, R.; Mika, M. Turistika a Jej Formy, 1st ed.; Prešovská Univerzita Grafotlač: Prešov, Slovakia, 2015; 550p, ISBN 978-80-555-1530-4. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A.; Sommerhalder, K.; Abel, T. Landscape and well-being: A scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, M.; Gross, S. Tourism research on adventure tourism—Current themes and developments. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 28, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhar, A.; Schauppenlehner, T.; Brandenburg, C.; Arnberger, A. Alpine summer tourism. The mountaineers’ perspective and consequences for tourism strategies in Austria. For. Snow Landsc. Res. 2007, 81, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmetoglu, M.N.Ø. The link between travel motives and activities in nature-based tourism. Tour. Rev. 2013, 68, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görner, K.; Mandzák, P. Miesto Turistiky a Športovo Pohybových Aktivít v Prírode v Spôsobe Života 16–18 Ročnej Populácie v Stredoslovenskom Regióne, 1st ed.; Fakulta humanitných vied Univerzity Mateja Bela: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2011; 109p, ISBN 9788055701899. [Google Scholar]

- Korvas, P.A.K. Aktivní Formy Cestovního Ruchu, 1st ed.; Masarykova univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2007; 149p, ISBN 978-80-210-4361-9. [Google Scholar]

- Team of Authors. Stupnice Technickej Obťažnosti. Available online: https://www.kstst.sk/pages/vht/stupne.htm#sac (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Team of Authors. Klasifikácie Obtiažnosti Lezenia. HO—Metropol Košice. Available online: http://ho-metropol.sk/lezenie-definicia/klasifikacie-obtiaznosti-lezenia/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Hansmann, R.; Hug, S.-M.; Seelanda, K. Restoration and stress relief through physical activities in forests and parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leader (Liaison Entre Actions de Développement de L’économie Rurale) Developing Walking Holidays in Rural Areas. “Rural Innovation”, Dossier No. 12.; LEADER European Observatory: Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- Kastenholz, E.; Rodriguez, A. Discussing the potential benefits of hiking tourism in Portugal. Anatolia 2007, 18, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall-Reinius, S.; Bäck, L. Changes in visitor demand. Inter-year comparisons of Swedish hikers’ characteristics, preferences and experiences. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 11, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongdejsri, M.; Nitivattananon, V. Assessing impacts of implementing low-carbon tourism program for sustainable tourism in a world heritage city. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengxiang, S.; Yunzhang, T.; Lin, L.; Eimontaite, I.; Ting, X.; Yan, S. An Exploration of Hiking Risk Perception: Dimensions and Antecedent Factors. In Environ. Res. Public Health; 2019; 16, p. 1986. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6603918/pdf/ijerph-16-01986.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Weber, K. Outdoor adventure tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.H.; Mackenzie, S.H. Multiple motives for participating in adventure sports. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesková, M. Cestovní Ruch: Pro Vyšší Odborné Školy a Vysoké Školy, 2nd ed.; Aha Fortuna: Praha, Czech Republic, 2011; 216p, ISBN 978-80-7373-107-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gučík, M.a.k. Výkladový Slovník: Cestovný Ruch, Hotelierstvo, Pohostinstvo, 1st ed.; Slovenské Pedagogické Nakl: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2006; 216p, ISBN 8010003603. [Google Scholar]

- Zelenka, J.; Pásková, M. Výkladový Slovník Cestovního Ruchu, 2nd ed.; Linde Praha: Praha, Czech Republic, 2012; 768p, ISBN 978-80-7201-880-2. [Google Scholar]

- Advetnure Travel Trade Association (ATTA). 2014. Available online: https://www.cabi.org/leisuretourism/news/24134 (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Hill, B.J. A Guide to Adventure Travel. Parks Recreat. 1995, 30, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Millington, K.; Locke, T.; Locke, A. Adventure travel. Travel Tour. Anal. 2001, 4, 65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A.M. Marketing and Managing Tourism Destinations, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; 596p, ISBN 978-0-415-67250-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pomfret, G. Mountaineering adventure tourists. A conceptual framework for research. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Breejen, L. The experiences of long distance walking: A case study of the west highland way in Scotland. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Kastenholz, E.; Rodrigues, A. Hiking as a relevant wellness activity—Results of an exploratory study of hiking tourists in Portugal applied to a rural tourism project. J. Vacat. Mark. 2010, 16, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, G.; Bramwell, B. The characteristics and motivational decisions of outdoor adventure tourists. A review and analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1447–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantala, O.; Hallikainen, V.; Ilola, H.; Tuulentie, S. The softening of adventure tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 18, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løvoll, H.S. The inner feeling of glacier hiking. An exploratory study of “immersion” as it relates to flow, hedonia and eudaimonia. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 19, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F.; Peters, M. Soft adventure motivation: An exploratory study of hiking tourism. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipp, D. Loving Them to Death? Sustainable Tourism in Europe’s Nature and National Parks; Federation of Nature and National Parks of Europe: Grafenau, Germany, 1993; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, F.; Liu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Duan, J.; Li, J. An overview of tourism risk perception. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of travel risk perception. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R.; León, C.J.; Carballo, M.M. The perception of risk by international travellers. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luh, Y. The Impacts of Perceived Risk in Senior Travel: Exploring the Moderating Roles of Destination Image and Involvement. Glob. Rev. Res. Tour. Hosp. Leis. 2018, 4, 521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Chhetri, P.; Arrowsmith, C.; Jackson, M. Determining hiking experiences in nature-based tourist destinations. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, P.; Tyrva¨inen, L. Frontiers in nature-based tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 10, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wo¨ran, B.; Arnberger, A. Exploring relationships between recreation specialization, restorative environments and mountain hikers’ flow experiences. Leis. Sci. 2012, 34, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valach, P.a.k. Charakteristika pohybové aktivity obyvatel Plzeňského regionu zjišťovaná v letech 2005–2009. Tělesná Kultura 2011, 1, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. Comparative analysis of tourist motivations by nationality and destinations. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Skallerud, K.; Chen, J. Tourist motivation with sun and sand destinations: Satisfaction and the Wom-Effect. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Prebensen, N.K.; Chen, Y.-L.; Kim, H. Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. Tour. Anal. 2013, 18, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, S.S.; Lee, C.-K.; Klenosky, D.B. The influence of push and pull factors at Korean national parks. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svarstad, H. Why hiking? Rationality and reflexivity within three categories of meaning construction. J. Leis. Res. 2010, 42, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STN 01 8025: Dokumentácia. 2006. Turistické Značenie. Available online: http://www.kst.sk/images/stories/Simko/TEXTY/stn%2001%208025-rukopis-pdf.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Švec, Š. Metodológia vied o Výchove: Kvantitatívno-Scientické a Kvalitatívno-Humanitné Prístupy; Iris: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1998; 300p, ISBN 8088778735. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; 792p, ISBN 978-0-470-46363-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Uysal, M.; Kim, J.; Ahn, K. Nature-based tourism: Motivation and subjective well-being. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caber, M.; Albayrak, T. Push or pull? Identifying rock climbing tourists’ motivations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddy, J.K.; Webb, N.L. The influence of the environment on adventure tourism: From motivations to experiences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 2124–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsdottir, G. “... sometimes you’ve just got to get away”: On trekking holidays and their therapeutic effect. Tour. Stud. 2013, 13, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidon, E.S. Why wilderness? Alienation, authenticity, and nature. Tour. Stud. 2019, 19, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimo’thy, S.; Mykletun, R.J. Play in adventure tourism—The case of Arctic Trekking. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 855–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kil, N.; Stein, T.V.; Holland, S.M. Influences of wildland-urban interface and wildlife hiking areas on experiential recreation outcomes and environmental setting preferences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 127, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Bricker, K.; Graefe, A.; Wickham, T. An examination of recreationists’ relationships with activities and settings. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CAI Hiking Scale of Difficulty (Club Alpino Italiano) | |

|---|---|

| T (Turistico) Hiking | Trails with well-evident paths that do not pose uncertainties or problems of orientation—country roads, agricultural roads and easy paths. They generally take place under the 2000 m. They require some knowledge of the mountain environment and a physical preparation to walk. |

| E (Escursionistico) Mountain hiking | Most common trails, pathless or footpath, can be not so evident. The orientation can be more difficult, but the direction is always clear. Trails are in higher altitudes with steep ascent or descent. Grass and rocky slopes partially with snow cover. Short sections with falling rocks but without the increased danger. There may be short climbing passages equipped with ladders, ropes and chains. They require a certain sense of orientation, some experience and knowledge of the mountainous territory, as well as footwear and adequate equipment (harness, carabiner, etc.). |

| EE (per Escursionisti Esperti) Challenging mountain hiking | Unmarked trails with a difficult terrain that is physically more demanding. Easy climbing, traverse of snow fields and troughs, exposed, slippery, grassy, or rock passages without climbing holds. Difficult rock sections with technically demanding climbs are not always secured by rope. Trails require good navigation skills; hikers need to follow mountain service warnings and hiking safety rules. Hikers need to be trained and experienced and do not suffer from dizziness. Adequate equipment (harness, carabiner, rope) is also required. Upper limit for hiking. |

| EEA (per Escursionisti Esperti, con Attrezzature) Alpine equipped trail | Equipped trails or Vie ferrate for which it is necessary to use self-assurance devices or climbing equipment (harness, heatsink, carabiner, lanyards and protective equipment as helmet, gloves). These trails require skills, preparation, experience and all requirements already mention for EE. |

| SAC Mountain and Alpine Hiking Scale (Schweizer Alpen Club) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Level | Path, Marking, Terrain | Requirements |

| T1 Hiking | Path: well developed and marked Marking: yellow Terrain: flat or slightly inclined, no danger of falling | No special footing is necessary, can be walked in trainers, navigation without a map is possible. |

| T2 Mountain hiking | Path: continuous route Marking: white-red-white Terrain: steep in parts, danger of falling not excluded | Some steady footing, trekking shoes recommended, basic navigation skills. |

| T3 Challenging mountain hiking | Path: Path not always visible. Exposed places are secured with ropes and chains or hikers need to use hands for balance. Marking: white-red-white Terrain: Some areas can be exposed with a danger of falling, gravel plains, steep and pathless terrain | Good steady footing, good trekking shoes, average navigation skills, basic alpine experience. |

| T4 +/− Alpine hiking | Path: Path not always available. Sometimes hikers need to use hands to keep going. Marking: white-blue-white Terrain: Mostly exposed, tricky grass heaps, rocky slopes, simple firn fields, glacier passages. | Familiarity with exposed terrain, stable trekking shoes are necessary, terrain assessment, good navigation skills, alpine experience, in a bad weather the way back can be difficult to find. |

| T5 +/− Challenging Alpine hiking | Path: Often pathless, individual simple climbing sections. Marking: white-blue-white Terrain: Exposed, challenging terrain, steep slopes, glaciers and firn field with danger of slipping | Mountaineering boots, very good navigation skills, good alpine experience, secure terrain assessment, basic knowledge in handling a pickaxe and rope. |

| T6 +/− Difficult Alpine hiking | Path: Mostly without a path, climbing sections up to II UIAA. Marking: Usually unmarked. Terrain: Often very exposed and challenging, steep slopes, glacier with a higher danger of slipping. | Excellent navigation skills needed. Proven alpine experience and familiarity with alpine equipment and technique. |

| I do hiking because: | |||||||||||

| I want to develop or maintain my phisycal fitness | I like to spend leisure time with family and friends | I like to explore nature | I like to relax/I like active rest | ||||||||

| Gro-up | Yes | No | Gro-up | Yes | No | Gro-up | Yes | No | Gro-up | Yes | No |

| 1 | 76.1% | 23.9% | 1 | 87.3% | 12.7% | 1 | 90.1% | 9.9% | 1 | 90.1% | 9.9% |

| 2 | 80.9% | 19.1% | 2 | 82.0% | 18.0% | 2 | 88.8% | 11.2% | 2 | 91.6% | 8.4% |

| 3 | 77.9% | 22.1% | 3 | 88.5% | 11.5% | 3 | 91.6% | 8.4% | 3 | 96.2% | 3.8% |

| 4 | 89.6% | 10.4% | 4 | 89.6% | 10.4% | 4 | 93.8% | 6.3% | 4 | 97.9% | 2.1% |

| How often do you go hiking: | ||||

| Group | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never/almost never |

| 1 | 21.1% | 25.4% | 39.4% | 14.1% |

| 2 | 32.6% | 19.1% | 37.6% | 10.7% |

| 3 | 42.0% | 16.0% | 35.9% | 6.1% |

| 4 | 66.7% | 2.1% | 22.9% | 8.3% |

| Do you go hiking in bad weather? | ||

| Group | Yes | No |

| 1 | 22.5% | 77.5% |

| 2 | 41.6% | 58.4% |

| 3 | 47.3% | 52.7% |

| 4 | 72.9% | 27.1% |

| The ideal hiking trail profile for you is: | ||||

| Gro-up | The profile of the hiking trail doesn’t matter to me | A flat plain start–finish | Start and Finish on an uphill and a valley in between | Start and finish in a valley and an uphill in between |

| 1 | 70.40% | 5.60% | 9.90% | 14.10% |

| 2 | 60.10% | 6.20% | 6.70% | 27.00% |

| 3 | 66.40% | 3.10% | 3.80% | 26.70% |

| 4 | 52.10% | 6.30% | 8.30% | 33.30% |

| You prefer: | ||||

| Gro-up | Long but gradual elevation | Short but steep elevation | The profile of the trail (elevation) doesn’t matter to me | Trails with minimal elevation |

| 1 | 31.00% | 7.00% | 36.60% | 25.40% |

| 2 | 21.90% | 11.80% | 47.80% | 18.50% |

| 3 | 29.00% | 9.20% | 51.90% | 9.90% |

| 4 | 33.30% | 4.20% | 35.40% | 27.10% |

| What type of hiking trail surface do you prefer? | ||||

| Gro-up | Asphalt | Gravel/Crushed stone | Natural earth surface | The surface doesn’t matter to me |

| 1 | 4.2% | 5.6% | 46.5% | 43.7% |

| 2 | 2.2% | 1.7% | 56.2% | 39.9% |

| 3 | 0.8% | 0.0% | 65.6% | 33.6% |

| 4 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 81.3% | 18.8% |

| What types of obstacles do you consider as a problem while hiking? | |||||||||||

| Mud | Roots | Rocks/Stones | Exposed places secured with ropes or chains | ||||||||

| Gro-up | Yes | No | Gro-up | Yes | No | Gro-up | Yes | No | Gro-up | Yes | No |

| 1 | 46.5% | 53.5% | 1 | 9.9% | 90.1% | 1 | 18.3% | 81.7% | 1 | 31.0% | 69.0% |

| 2 | 54.5% | 45.5% | 2 | 6.2% | 93.8% | 2 | 11.2% | 88.8% | 2 | 37.1% | 62.9% |

| 3 | 43.5% | 56.5% | 3 | 6.9% | 93.1% | 3 | 9.9% | 90.1% | 3 | 32.1% | 67.9% |

| 4 | 62.5% | 37.5% | 4 | 25.0% | 75.0% | 4 | 25.0% | 75.0% | 4 | 37.5% | 62.5% |

| How do you orientate yourself in environment? | |||||||||||

| By using trail signs, markers and blazes | By using mobile applications (mapy.cz, hiking.sk and others) | By using paper tourist maps | |||||||||

| Gro-up | I never use them | I use them sometimes | I use them always/often | Gro-up | I never use them | I use them sometimes | I use them always/often | Gro-up | I never use them | I use them sometimes | I use them always/often |

| 1 | 6.7% | 34.4% | 58.9% | 1 | 10.1% | 47.3% | 42.6% | 1 | 63.6% | 29.5% | 6.8% |

| 2 | 4.5% | 32.9% | 62.7% | 2 | 8.7% | 46.3% | 45.0% | 2 | 56.5% | 38.3% | 5.2% |

| 3 | 1.9% | 38.9% | 59.2% | 3 | 10.9% | 52.8% | 36.2% | 3 | 33.2% | 50.7% | 16.1% |

| 4 | 4.2% | 27.1% | 68.6% | 4 | 27.2% | 46.9% | 25.9% | 4 | 20.0% | 58.8% | 21.2% |

| Question | Chi-Square Linear-by-Linear Association | df | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I do hiking because: | I want to develop or maintain my physical fitness | 1.500 | 1 | 0.221 |

| I like to spend leisure time with family and friends | 0.941 | 1 | 0.332 | |

| I like to explore nature | 0.835 | 1 | 0.361 | |

| I like to relax / I like active rest | 5.041 | 1 | 0.025 | |

| Do you go hiking in bad weather? | 27.530 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Which country is attractive for you? | Wide valleys with hills | 8.685 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Straits and steep valleys with high mountains | 0.246 | 1 | 0.620 | |

| Hill landscape without significant valley | 7.700 | 1 | 0.006 | |

| Wold | 24.968 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Lowlands around rivers | 0.037 | 1 | 0.847 | |

| Problems with difficult conditions along the route? | Mud | 0.285 | 1 | 0.593 |

| Roots | 4.963 | 1 | 0.026 | |

| Rocks/Stones | 0.207 | 1 | 0.649 | |

| Exposed places secured with ropes or chains | 0.055 | 1 | 0.814 | |

| Sharp decline | 2.527 | 1 | 0.112 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molokáč, M.; Hlaváčová, J.; Tometzová, D.; Liptáková, E. The Preference Analysis for Hikers’ Choice of Hiking Trail. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6795. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116795

Molokáč M, Hlaváčová J, Tometzová D, Liptáková E. The Preference Analysis for Hikers’ Choice of Hiking Trail. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6795. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116795

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolokáč, Mário, Jana Hlaváčová, Dana Tometzová, and Erika Liptáková. 2022. "The Preference Analysis for Hikers’ Choice of Hiking Trail" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6795. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116795

APA StyleMolokáč, M., Hlaváčová, J., Tometzová, D., & Liptáková, E. (2022). The Preference Analysis for Hikers’ Choice of Hiking Trail. Sustainability, 14(11), 6795. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116795