Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a strong impact on the functioning of the event industry. This article aims to present the impact of infection control measures on the event sector. In addition, the article compares the infection control measures implemented in Poland and Norway. The COVID-19 infection measures analysis is the first stage of a project to build the resilience of the event sector. The study was conducted based on secondary data (analysis of documents and public statistics, with the support of the literature). The research used the descriptive method and comparisons. The results of the study confirmed the following research hypotheses according to which: (1) uncertainty is conducive to overreactions, both of the government and entities from the event sector; (2) mutual trust between government and society reduces the need for restrictions; and (3) the lack of mutual trust between government and society increases uncertainty. Furthermore, the inability to meet people, limited access to culture, and the need to work from home contributed to the deterioration of societies’ quality of life and mental health. This means that the pandemic has an adverse impact on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3 and 8).

1. Introduction

Until now, the events industry, including festivals, meetings, conferences, exhibitions, sports, and a range of other events, has been considered one of the fastest-growing forms of tourism [1,2,3,4,5], providing many economic benefits, such as increased expenditures, the creation of employment, labor supply growth, and an increase in the standard of living [4]. According to [6], this sector is the primary source of income in many places worldwide. Festivals also have significant social and cultural roles and are viewed as a tool for marketing and destination image-making [7,8,9,10]. Moreover, festivals and events foster regional development [11] and can provide tangible and intangible benefits for communities [12]. Mair and Smith [13] are of a similar opinion, emphasizing that events are socially, culturally, politically, naturally, and economically important phenomena. Therefore, according to the authors, there is a need for extensive research on the potential of events as drivers of sustainable development. This is also supported by the research of Fredline et al. [14], who insists that events contribute to significant economic, entertainment, social, and developmental benefits. Moreover, festivals and events influencing the development of a region [11] can provide tangible and intangible benefits for communities [12]. Every year, many attendees participate in events and festivals that contribute to promoting destinations, cultural awareness, employment opportunities, and economic growth [15].

It should be noted that events are perceived as tools for building broadly understood sustainable development [16,17]. Considering the social perspective, events allow to meet the needs in the field of meetings and creating relationships, contributing to building the community and human capital [18,19]. In addition, research to date on social impact indicates that events can function as powerful accelerators of change, particularly regarding social cohesion, integration, and the creation of a place-based identity [20,21]. In economic terms, events can be a catalyst for economic development, offering many tangible (employment impacts and tax revenues) and intangible (civic pride) benefits to destinations that together can become a rich source of local prosperity [20,22]. Proper accounting for the costs and benefits of organizing festivals must also consider the assessment of its impact on the environment. In festival studies, environmental impact studies have not been undertaken as often as analyses of the socio-cultural impact of festivals [16,23]. Recently, however, there has been an increase in research interest in better understanding the environmental impact of festivals [24,25]. Research to date indicates that festivals can provide a valuable means to promote more sustainable technologies, attitudes, and behaviors [13,26].

The rapidly developing COVID-19 pandemic determines the way societies function, both in economic and leisure activities [27]. Since the onset of the pandemic, most events have been restricted or completely shut down, wiping out thousands of jobs and creating severe disruptions in the cultural and social value these events provide for the community. Therefore, it is believed that the event industry and the entire tourism industry will be among the most affected by the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic [28].

A global pandemic requires a global response. To some extent, such a response has been given. International organizations such as the World Health Organization (WTO), the United Nations (UN), and the European Union (EU) have contributed to essential international cooperation in combating the pandemic.

The WHO’s surveillance of the virus, starting with the first reported cases in Wuhan, China, and their continuous assessments and information, such as the declaration of the outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020, and as a global pandemic on March 11 [29], have been of significant consequence. Additionally, the UN has played an important role by assisting all governments through both the response to and recovery from the virus, especially in low- and middle-income countries [30].

Within the EU, supranational regulation has been relatively limited. Generally, the possibility of Member States implementing measures that violate EU law, importantly the four freedoms that govern the movement of goods, persons, services, and capital within the EU, is limited. In a crisis such as this, however, there are far-reaching exemptions. Consequently, infection control measures have mainly been implemented at the national level but with many efforts for coordination at the EU level. Most of the coordination efforts have been by way of nonbinding recommendations, such as that of the Council of the European Union on a coordinated approach to the restriction of free movement in response to the COVID-19 pandemic [31].

In some cases, Member States also issued common hard law measures, such as when all Schengen Area Member States approved a plan proposed by the EU Commission that foresaw the closure of the external borders of the territory [32]. In addition, many other organizations and international corporations have been dedicated to combating the pandemic and its consequences. However, implementing measures regulating the rights and duties of citizens and requests and recommendations has mainly been carried out by nation-states.

To date, the unknown threats have caused great chaos, fear, and awareness among people. The triggered panic led to many countries across the world going into lockdown mode [33]. With the hope of curbing the spread of the virus, all countries implemented various infection control measures. The approach taken to combat this novel enemy has been different from country to country. Epidemical, cultural, geographical, administrative, demographical, financial, and social differences both call for and allow for different approaches. The differences in content and form, as well as the process leading up to and the enforcement of the control measures, reflect this. In almost all countries, the measures have dramatically affected businesses, regardless of their profile or size. The event sector might face similar challenges in the future. Therefore, it is crucial to learn how the current pandemic has been handled to improve or strengthen the sectors’ resilience for future unpredictable crises.

This article identifies measures and the implementation and enforcement of these measures that have had an impact on the festival and event sector in Norway and Poland. The research also attempts to systemize the measures, compare the experiences of the two countries, and analyze the results. The core question of the study is how the Norwegian and Polish governments have handled infection control measures in the festival and event sector and what can be learned from that.

The study compares Poland and Norway due to the different approach to the restrictions introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Norway, the introduced restrictions were rather recommendations, while in Poland they were orders and bans (with the threat of a financial penalty for breaking orders and bans). Moreover, these countries, despite their similar size, are diversified both in terms of socioeconomic and political aspects. Norway has a much smaller population (5.3 million) and population density (16 people/km2) than Poland (38.4 million; 123 people/km2, respectively). However, Norway has a higher GDP per capita ($ 74.0 thousand) than Poland ($ 33.7 thousand). Moreover, Norway does not belong to the EU, contrary to Poland [34].

The event sector is developing in both countries as an important element of social and economic life. It provides about 220,000 jobs in Poland and about 30,000 in Norway. About 7000 mass events are held annually in Poland, while about 1000 events are held in Norway [35,36]. In both countries, as a result of the pandemic, there were significant limitations in the functioning of the event industry. According to estimates, the decline in revenues in the cultural sector alone in Norway reached 30% in 2020 compared with 2021. In Poland, losses measured by the decrease in the number of mass events organized in 2020 exceeded 70% [37]. The restrictions related to the pandemic in both countries were imposed at different times, and with varying intensity and form.

The main aim of this article is to present the impact of infection control measures on the event sector. In addition, the study aims to achieve the following research objectives:

- −

- To provide a comparison between Norway and Poland in terms of measures and processes;

- −

- To indicate possible general solutions for the event industry in the event of a similar situation in the future.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the existing research. Section 3 introduces the methods and research context. Section 4 compares the pandemic situation with respect to the event sector in both Poland and Norway. Finally, Section 5 includes a discussion and a conclusion.

2. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Event Sector: A Literature Review

As indicated by Qiu et al. [38], there have been many significant pandemics in the history of humanity that have caused crises that have had a negative impact on health, the economy, and national security. To understand the essence of pandemics, the author indicates its features: a wide geographic extension, disease movement, novelty, severity, high attack rates and explosiveness, minimal population immunity, and infectiousness.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all socioeconomic spheres, including the event industry and its stakeholders. Despite the limited time since the outbreak of the pandemic, many scientific studies in this field have been published. The publications address various issues, from the obvious economic crisis of the event industry to the social consequences of the pandemic.

Events and festivals, apart from the fact that they are usually very popular, increase tourists’ expenses and provide sources of income and employment. In addition, events and festivals can provide a platform for promoting and building awareness of the host region [28]. The announcement of the global COVID-19 pandemic by WHO in March 2020 meant that the event sector had to cancel, postpone, or otherwise reorganize events and festivals. In addition, the pandemic also caused additional difficulties such as total lockdowns, job precariousness, travel restrictions, ongoing uncertainty, lost income, and job losses by employees associated with the sector (e.g., hospitality, travel and tourism, and retail) [39,40].

In addition, with the outbreak of the pandemic, there were also discussions about its economic effects. Many companies in the event industry suffer from a capital shortage, despite changes in the way they conduct their business (such as live chat, webinars, online discussion shows, podcasts, etc.) [41]. According to Correia et al. [42], social interaction is limited during a pandemic, so economic activity based on these interactions is reduced. Moreover, in a pandemic, economic activity is reduced due to a decreasing consumption and supply of labor (reduced risk of infection). On the other hand, firms reduce investment in response to increased uncertainty. Governments of many countries, based on the available data on COVID-19 (e.g., new cases and mortality), are faced with the choice of whether to loosen, maintain, or tighten restrictions. This choice is most often a compromise between saving human life and saving the economy. Increasing the restrictions reduces the final number of deaths but has negative consequences for the economy (e.g., companies go bankrupt, employees lose their jobs, and so on) [43].

Interesting results were obtained by Andersen et al. [43] who studied the impact of government-imposed restrictions during a pandemic on consumer spending in countries with similar exposure to the pandemic (Denmark and Sweden). The research results indicate that most of the economic contraction is caused by the virus itself and occurs regardless of whether governments mandate social distancing or not. Similar conclusions are also presented by Lin and Meissner [44], who studied the impact of non-pharmaceutical public interventions on the spread of infectious diseases in the U.S. The authors’ research results indicate that staying at home is only weakly associated with the slower increase in COVID-19 cases. The authors’ also note that job losses were not higher in the U.S. states that implemented a stay-at-home mandate during the COVID-19 pandemic than in states that did not. Demirgüç-Kunt et al. [45] also studied the economic impact of non-pharmacological interventions in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe and Central Asia. The authors’ research results show that interventions of this type have led to a 10% decline in economic activity across the region. On average, countries that implemented such interventions in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic have better short-term economic outcomes and lower mortality than countries that introduced interventions in the later stages of the pandemic. Undoubtedly, one should agree with Qiu et al. [38] that the pandemic poses a severe threat to humanity and the economy. Economic losses can make the economy unstable due to direct costs, long-term burdens, and indirect costs.

The situation of the event industry during the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented. Mohanty et al. [28] rightly emphasize that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic cannot yet be thoroughly investigated due to the pandemic’s short duration and the lack of an end in sight. The exact determination of losses will most likely not be possible due to the numerous connections of the event industry with other industries, e.g., tourism, transport, accommodation, and gastronomy [33]. Researchers indicate that a recovery of the industry to the pre-pandemic situation will be possible but will need external support from both central and local authorities. Top-down support is important to help see the pandemic end and subsequently help the industry restart [41,46]. Recovery will require support, broadly understood not only as financial but also as multifaceted support, allowing us to recreate conditions similar to those prior to the pandemic, including clear regulations for the event industry. In addition, event services should be supported by government activities but with the involvement of entrepreneur organizers [27]. The presence of both parties—governmental and entrepreneurial—is equally important in restoring balance in the event business. This may explain the changes in the organizers’ approach to their work caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Before the pandemic, pride was the essential feature of professional organizers. During the pandemic, skills related to the current situation turned out to be more important. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a shift from abstract feelings to practical skills [4,47].

Although the current pandemic is difficult to compare with previous crises, the temporary nature of the situation is emphasized, which gives greater hope for a return to the pre-pandemic state. Rowen [48] emphasizes that it can only constitute a certain threshold for the necessary changes occurring in the event sector. These changes include all kinds of virtual technologies that will help the industry survive [6]. While Madray [41] believes this is merely a way of surviving, some solutions are projected to stay in the industry for the longer term, not only due to necessity but also because of their benefits [49].

The limitations in organizing events and the temporary inability to attend events have, paradoxically, contributed to an increase in awareness of the importance of events in many aspects, including socially [50]. In particular, live events are a platform for building relationships and providing impressions and emotions, which are important aspects of events. Olson [51] points out that, despite the COVID-19 pandemic and numerous restrictions, some people still flock to informal events. On the other hand, some people feel fear related to mass gatherings, and there is a risk that this feeling will remain after the pandemic, making it difficult for the event industry to regain balance [52].

However, as Goldblatt and Lee [53] emphasize, the pandemic is not the only threat to the event industry. During the global recession of 2007–2009, the event industry was also severely hit, indicating a need to develop robust strategies to overcome sudden and uncertain situations that can pose a threat to the event industry.

The rapidly evolving COVID-19 pandemic reminds us about the strong need to return to sustainable practices and adjust priorities to manage globally synchronized threats such as pandemics [54]. The prospect of achieving the main goal of humanity, recognized in 2015, which is sustainable development expressed by the United Nations 2030 Agenda and SDG (17 Sustainable Development Goals) [55] has deteriorated in connection with the pandemic [56].

Therefore, a global change is required to transform complex and interconnected socioeconomic and environmental systems in order to build a more resilient and sustainable future. Munasinghe [54] points to seven key lessons related to the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of sustainable development. From the point of view of the event industry, two of them are of particular importance. First, there is a need to develop integrated, long-term, and global solutions to tackle emerging emergencies comprehensively (rather than fragmented, reflexive responses). Second, risk analysis and management tools need to be better understood and used to deal with extreme situations better.

3. Research Materials and Methods

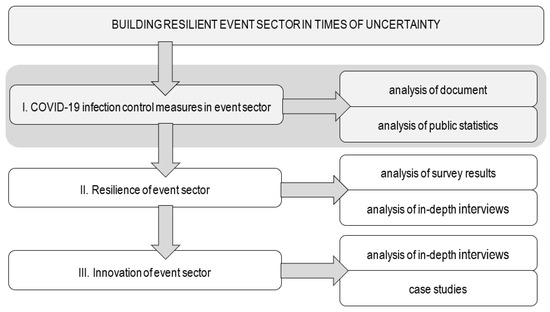

The proposed research is part of a larger project. The COVID-19 infection measures analysis is the first stage of a project to build the resilience of the event sector. The presented research is based on the analysis of documents and public statistics with the support of the literature. In future stages of the project, the results of the respondents’ research, the results of in-depth interviews with event organizers, and case studies from Poland and Scandinavian countries will be analyzed. The analyses carried out for the current stage of the study have created the necessary foundations for the next steps of the project that are underway (Figure 1). An important element of the research is the comparison of solutions from different countries.

Figure 1.

Research context.

The research was carried out on the basis of secondary data. This is data already collected and published in any form [57]. Secondary data is a valuable and not always appreciated source of research data which is equally valuable as primary data [58]. The presented research uses the literature, legal acts, and government and official statistics from selected countries.

The presented research covers three main stages: (1) secondary data collecting and reviews, (2) infection control measures in Poland and Norway, and (3) a Poland–Norway comparison. In the first stage, secondary data necessary for analyses were collected and reviewed. These are both the regulations introduced from March 2020 to May 2021 in Poland and Norway, as well as pandemic data.

The second stage of the research covers the characteristics of the situation in terms of infection control measures, taking into account the situation of the event sector in Poland and Norway. At this stage, a descriptive method was used, thanks to which the existing condition in both studied countries was characterized without indicating the causes and dependencies [59,60]. The aim was to accurately describe the situation, forming the basis for further analyses, including comparisons.

The third stage of the research involves comparing the pandemic situation in Poland and Norway in terms of the limitations of the event sector. The comparison was used because, as one of the basic tools of analysis, it strengthens the power of description and helps to focus attention on similarities and contrasts [61,62]. Revealing the similarities and differences in the course of the pandemic, including the event sector, helped to identify the reasons for this state of affairs and the possible practical implications. Additionally, dates of restrictions and mitigations were compared with the number of COVID-19 cases in Poland and Norway. Such a comparison made it possible to refer to the level of reaction of the governments of both countries.

Four research hypotheses were formulated with reference to the COVID-19 pandemic and its course in Poland and Norway as well as the impact on the event industry. The study proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Uncertainty is conducive to overreactions of the government, which had a negative impact on the event sector.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Mutual trust between government and society reduces the need for restrictions.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

The lack of mutual trust between government and society increases uncertainty.

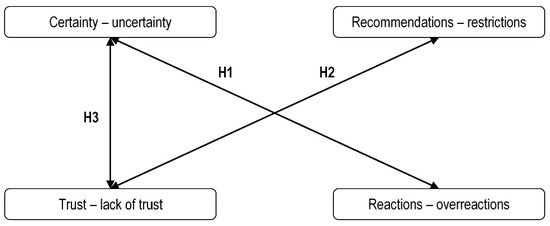

Research hypotheses have been embedded in the context of four processes and phenomena accompanying the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the following processes and phenomena have been listed as opposites: certainty—uncertainty, trust—lack of trust, reactions—overreactions, and recommendations—restrictions. Figure 2 illustrates the embedding of research hypotheses.

Figure 2.

Research hypothesis.

4. Comparison of the Poland and Norway Event Sector during the Pandemic

The course of the pandemic in Poland and Norway shows both similarities and differences in terms of infections and deaths. The differences relate mainly to the initial phase of the pandemic, in that the COVID-19 virus arrived in Poland late. However, for both countries, each successive wave culminates in more deaths than in the previous wave.

The differences in mortality rates are likely due to the health system capacity (not only for COVID-19 but also for other diseases). In Norway, each of the 356 municipalities had an infectious disease doctor. They were responsible for contact tracing, quarantine, isolation, or population testing in the event of a local outbreak. In Poland, which has a population seven times larger, there were 479 medical specialists in infectious diseases. Such a proportion led to the general conclusion that the health service was ineffective, as evidenced by the introduction of the so-called tele-advice, even in advanced diseases unrelated to virus infection, postponing essential operations or closing entire hospital departments.

In Norway, infection control measures were adopted by the Norwegian government, represented by the Ministry of Health and Care Services. The decisions were heavily influenced by science, and the Ministry and the Norwegian Directorate of Health cooperated closely with the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The accounts of the infection control measures are based mainly on the press releases from the Norwegian Government and the timeline presented on the government’s webpage [63]. The approach to limiting the virus spread has been based on the Norwegian concept ‘dugnad’ (collective effort). By linking the measures to this firmly rooted tradition, they appealed to the population’s sense of collective effort (dugnadsånd) and solidarity. This was probably a factor in the success of coordinating the actions of the population against the virus [64]. The reality of this was later questioned, as the measures were, in fact, not evenly distributed or handled through a collective effort but rather placed much heavier burdens on parts of the population and certain sectors of the economy. Infection control measures were in the form of either rules, recommendations/guidelines, or advice [65,66].

Traditionally, there has been a strong cooperation between the government and the labor/employers’ organizations. This has also been argued to have been an advantage in the pandemic [65]. However, due to the special nature of the events and festival sector (e.g., they are organized to a much lesser extent than most other sectors), they might not have taken much advantage of this cooperation due to a lack of representation.

Table 1 and Table 2 present restrictions and mitigations introduced in Poland and in Norway in chronological order. The pandemic severely disturbed the governance system of almost every country. It is true that some common features of introducing particular restrictions in socioeconomic life are to be noted, but some countries tried to develop their own model of fighting the pandemic. The governments of Poland and Norway took a stance on decisive remedial action from the very beginning, with the best interests of every citizen in mind.

Table 1.

Event sector restrictions and mitigations in Poland during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2.

Event sector restrictions and mitigations in Norway during the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the priority restrictions was the quite controversial lockdown, which was intended to minimize interpersonal contact and, consequently, limit the spread of the virus. According to the public, it was one of the most important components of Norwegian and Polish success in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the procedures themselves and the way they were implemented in social life were completely different.

An important condition in the fight against the pandemic and compliance with all sanitary regimes is public trust in the government’s actions. In Norway, the so-called contact tracking team indicated that approximately 2.5 thousand people monitored the spread of the virus. The inhabitants of Norway had an understanding attitude about the decision to lock down and accepted the subsequent restrictions. Visible trust in decision-makers and health services did not increase the additional fear of losing lives.

In Poland, however, the process of imposing further restrictions was completely different. The political conflicts between groups that clashed over the restrictions were not conducive to the fight against the coronavirus. The effect of this procedure was the negation of any decision to introduce further recommendations or restrictions. The comments and criticism of the government were pervasive, especially after a month of isolation. The principal criticism was about the lack of adequate research on the effectiveness of wearing protective masks to cover the mouth and nose. The bans on business activities in certain industries, such as hairdressing and cosmetics, were criticized.

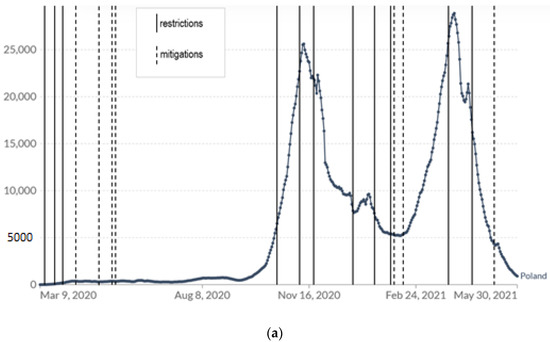

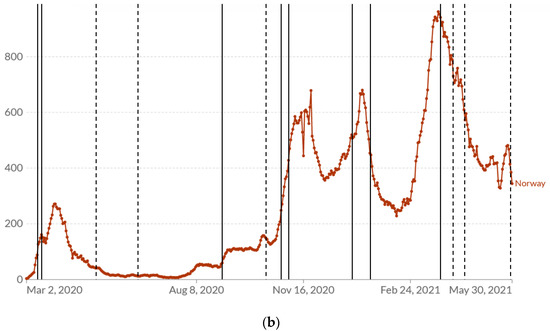

Figure 3 presents dates of restrictions and mitigations compared with the number of cases in Poland and Norway. There are apparent differences between the studied countries. In Poland, in the first phase of the pandemic, numerous rigid restrictions were introduced, which can be interpreted as an overreaction with a small number of cases. It is also visible that the restrictions are unevenly distributed over time and absent during the holiday season. Restrictions outweigh mitigations. In Norway, activities are more spread out over time. The mitigations were introduced at a slower pace.

Figure 3.

(a) Event sector restrictions and mitigations compared with the number of COVID-19 cases in Poland (b) Event sector restrictions and mitigations compared with the number of COVID-19 cases in Norway. Source: [73].

Table 3 presents the list of restrictions introduced in Poland and Norway, divided into the three waves of the pandemic, highlighting the similarities and differences. Some restrictions apply directly to the event industry. In both countries, a ban on organizing mass events was introduced, setting limits on the number of participants, which were then tightened; in the case of Poland, there was a complete ban on gatherings. Some of the restrictions that applied to the entire society also affected the event industry in both countries, including restrictions related to the need to maintain the sanitary regime, socially distance, or not leave the house without a clear need.

Table 3.

COVID-19 measures in Poland and Norway: a comparison.

The financial effects of the pandemic hit the festival and event industry especially hard. The Norwegian Corona Commission has, however, concluded that, if the authorities in March 2020 had waited longer to implement the restrictions, the consequences would probably have been even worse [65]. The immediate effect of the pandemic for the festival and event industry was a dramatic reduction in activity due to cancellations and/or a serious downscaling of events. This led to temporary and permanent layoffs and reduced or lost revenue. These dramatic effects of the measures were visible within the first months. Based on the number of temporary layoffs in the culture, entertainment, and other services, the volume was reduced by 60%. It is estimated that the value creation in the sector was cut almost in half in the first half of 2020. The activity rose in the second half of 2020, but it was still 27% lower in Q4 than in 2019 [65]. The cultural sector expects a 45% reduction in turnover in 2021 if control measures are continued, resulting in a loss of NOK 17 billion (Rapport, 2020). The financial losses were to some extent recovered through financial state aid for the sector. However, we might still see negative long-term effects. There is a need for continuity in this business, and for many, it might be difficult to start up again after a long shutdown period.

In March 2020, the meetings and events industry in Poland was shut down, and a large part of it was frozen for fifteen straight months. The research conducted by the Meetings and Events Industry Council shows that all entities recorded a decrease in revenues in the period from March 2020 to February 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic (compared with the same period a year earlier). The average decrease in the number of projects implemented in 2020 compared with 2019 is 82%, and the average decrease in annual revenues is as much as 73%. Moreover, 64% of respondents had problems maintaining financial liquidity. At the end of February 2021, contracted projects accounted for only 6% of the total number of projects implemented in 2019. In addition, 35% of companies thus far have no projects for 2021. Approximately 38% of companies have considered suspending or closing their operations. According to the research, government assistance aimed at entrepreneurs covered only 28% of losses. As a result of receiving a small amount of help from the government, it was necessary to reduce the operating costs, the fastest way of which was to cut employment. According to the research by the Meetings and Events Industry Council, the average reduction in employment was 63%, with a greater decrease in employment under B2B contracts, commissioned contracts, work-related contracts, and managerial contracts (72%) compared with employment contracts (26%) [68].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The necessity of introducing restrictions results from the need to protect the health of the population. In a situation of a threat to health and life, the problems of the functioning of the economy and its sectors recede into the background. Although the pandemic affected all socioeconomic spheres, the event industry was particularly vulnerable and suffered disproportionately, which has been confirmed by research [28,41,46,52]. This oversensitivity of the event industry in a pandemic is related to the mass nature of events and the direct contact among people, which is also confirmed by Mohanty et al. [28]. At the same time, it should be emphasized that, while the event industry serves important social purposes for the population [38], they do not have to be satisfied in the first place. Thus, the restrictions negatively affected the functioning of the event industry. Lockdowns have caused the industry to collapse on an unprecedented scale [27].

The imposition of additional restrictions in both countries was related to the situation at the time, determined by the level of morbidity and mortality as a result of COVID-19, as well as the social mood. However, differences in these societies’ approaches to change were visible. In Norway, government actions were generally recognized by society, which trusted its authorities overall. In Poland, government actions were exposed to considerable social criticism, resulting both from the attitude of the population toward the authorities and from the attitude of the authorities toward society. In Norway, the restrictions were, in large part, in the form of recommendations (according to: Hypothesis 2); in Poland, some restrictions were enforced under pain of penalties (according to: Hypothesis 3). In retrospect, the first quite restrictive COVID-19 measures, proposed when the incidence rate was low, were exaggerated. This was the case in both surveyed countries (according to: Hypothesis 1). The importance of intuition in planning and implementing restrictions is evidenced by their catastrophic effects on economic indicators, especially in particularly sensitive industries, such as the event industry. This is confirmed by research results already appearing in the literature. In addition, our findings confirm the conclusions of researchers emphasizing that the final effects caused by a pandemic are difficult to clearly estimate due to its short duration [28,52]. Most likely, this will be the direction of research that will be undertaken in the near future. It also seems important to look for an answer to the question of what could have been done differently or whether the paralysis of the event industry was necessary. According to the findings, the differences between the two countries in the mechanism of introducing restrictions were significant, while the effects for the event industry were quite similar.

At the same time, the significant role of government actions in recovery from the pandemic is emphasized. This role is important in both countries, indicating not only the need for financial but also nonfinancial support [12,46]. Due to the complexity and mass nature of the event industry, it is difficult to develop a mandatory model of conduct, but rules and regulations that are overly complex to implement also have a negative impact on the industry. Cooperation between enterprises and authorities, aimed at mutual understanding and reaching a compromise, is important [27]. This was not the case during the current pandemic. However, it may be an important lesson for the future. Mair and Smith [13] hope that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will encourage people and organizations related to the event industry to appreciate the value of the environment, livelihoods, and other people more and will lead to more sustainable practices in the future.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have a particularly negative impact on the achievement of at least two of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), i.e., SDG 3, good health and quality of life, and SDG 8, economic growth and decent work. The pandemic has undoubtedly affected the aspect of good health and quality of life, not only due to the COVID-19 disease but also the negative effects associated with closing communities at home. The inability to meet people, limited access to culture, and the need to work from home contributed to the deterioration of the quality of life and mental health of societies. Taking into account SDG 8, economic growth, and decent work, in the event industry and industries related to this activity, there was a radical reduction in employment due to limitations in the organization of events, which resulted in negative effects on economic growth.

The studies presented have some limitations. Also concerning the presented research, one of them is the lack of comparability of figures in the event industry. This results from different approaches to public statistics and different definitions of the event industry and the companies that constitute it. Another limitation is the need to narrow down the analysis to two countries. More countries for comparison would perhaps bring more generalized conclusions, but due to the amount of data and information, two countries were selected.

In terms of managerial implications, it should be emphasized that the experience already gained in the event industry in both countries indicates the need to develop procedures of conduct that will help avoid misinformation in the future. Especially in Poland, it would be worth limiting information chaos and ensuring a greater predictability of regulations.

The development of procedures would allow for the introduction of restrictions on time and the possibility of prior preparation of the organizers. The predictability and clarity of regulations should be a key factor in reducing disorganization in the work of the industry. Due to the complexity of the event industry, different types of events require different procedures. The division of the industry should be made according to the number of participants (mass events pose a greater threat), duration (events lasting more than a few hours are characterized by a greater level of risk), or the possibility of maintaining distance between participants (which is particularly difficult at culinary events or fairs where direct sales are conducted).

An important step should be broadly understood cooperation, not only between entities from the industry but also between the organizers and the central and local governments. Established relationships help build trust and are a good basis for cooperation in dealing with the pandemic. This element is much better developed in Norway, although it is emphasized that the event sector is not yet represented in the field of government cooperation with employee organizations [65]. Such cooperation shortens the distance and helps to develop the necessary solutions. Furthermore, collaboration between actors in the industry should be the basis of healthy competition. With cooperation, it is easier to support each other and exchange experiences. On the basis of cooperation, including international cooperation, a list of good practices for the event industry could be developed and published on a widely available platform.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, and visualization: D.J., V.H.L., D.K., L.O., C.D.-J., M.S. and G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is co-financed by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange within the Urgency Grants program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The study did not report any data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Crompton, J.L.; McKay, S.L. Motives of visitors attending festival events. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egresi, I.; Kara, F. Motives of tourists attending small-scale events: The case of three local festivals and events in Istanbul. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2014, 14, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Event Studies. Theory, Research, and Policy for Planned Events; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Janeczko, B.; Mules, T.; Ritchie, B. Estimating the Economic of Festivals and Events: A Research Guide; CRC for Sustainable Tourism: Gold Coast, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Diedering, M.; Oklevik, O. Profile, patterns of spending and economic impact of event visitors: Evidence from Warnemünder Woche in Germany. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 18, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H. COVID-19: An opportunity to review existing grounded theories in event studies. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2021, 22, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Getz, D. Stakeholder management strategies of festivals. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2008, 9, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragin-Jensen, C.; Kwiatkowski, G. Image interplay between events and destinations. Growth Chang. 2019, 50, 446–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duran, E.; Hamarat, B. Festival attendees’ motivations: The case of International Troia Festival. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2014, 5, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Oklevik, O.; Hjalager, A.-M.; Maristuen, H. The assemblers of rural festivala: Organizers, visitors and locals. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Analyzing the role of festivals and events in regional development. Event Manag. 2008, 11, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Chen, J.S. Festival visitor motivation from the organizers’ points of view. Event Manag. 2002, 7, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Smith, A. Events and sustainability: Why making events more sustainable is not enough. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1739–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredline, L.; Jago, L.; Deery, M. Host Community Perceptions of the Impacts of Events: A Comparison of Different Event Themes in Urban and Regional Communities; CRC for Sustainable Tourism: Gold Coast, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.K.; Mjelde, J.W.; Kwon, Y.J. Estimating the economic impact of a mega-event on host and neighbouring regions. Leis. Stud. 2015, 36, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Lundberg, E. Commensurability and sustainability: Triple impact assessments of a tourism event. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, D.; Ossowska, L. Food Festival Exhibitors’ Business Motivation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tölkes, C.; Butzmann, E. Motivating Pro-Sustainable Behavior: The Potential of Green Events—A Case-Study from the Munich Streetlife Festival. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Jong, A.; Varley, P. Food tourism and events as tools for social sustainability? J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G.; Mourato, S.; Szymanski, S.; Ozdemiroglu, E. Are We Willing to Pay Enough to ‘Back the Bid’? Valuing the Intangible Impacts of London’s Bid to Host the 2012 Summer Olympic Games. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisker, J.K.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Hjalager, A.-M. The translocal fluidity of rural grassroots festivals in the network society. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2021, 22, 250–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Armbrecht, J.; Lundberg, E. Estimating use and non-use values of a music festival, Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 12, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolles, H.; Söderman, S. Addressing ecology and sustainability in megasporting events: The 2006 football world cup in Germany. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsford, I.F. Actualizing environmental sustainability at Vancouver 2010 venues. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2011, 2, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Laing, J.H. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of sustainability-focused events. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K. Festivals Post Covid-19. Leis. Sci. 2021, 43, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.; Dhoundiyal, H.; Choudhury, R. Events Tourism in the Eye of the COVID-19 Storm: Impacts and Implications. In Event Tourism in Asian Countries: Challenges and Prospects, 1st ed.; Arora, S., Sharma, S., Eds.; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Rolling Updates on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- UN. How is the United Nations Responding to the Pandemic? Available online: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/how-united-nations-responding-%C2%A0-pandemic (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- EU Council. Council Recommendation (EU) 2020/1475 of 13 October 2020 on a Coordinated Approach to the Restriction of Free Movement in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020H1475 (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- EU Council. Conclusions by the President of the European Council following the Video Conference with Members of the European Council on COVID-19. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/03/17/conclusions-by-the-president-of-the-european-council-following-the-video-conference-with-members-of-the-european-council-on-covid-19/ (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Kalawapudi, K.; Singht, T.; Vijay, R.; Goyal, N.; Kumar, R. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on festival celebrations and noise pollution levels. Noise Mapp. 2021, 8, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT. Economy and Finance. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Report Meetings and Events Industry in Poland, Polish Tourist Organization, Toruń-Warszawa. 2020. Available online: https://www.pot.gov.pl/attachments/article/148/RAPORT%202020_PL_14.09.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021). (In Polish)

- Innovasjon Norge, Norge Som Bærekraftig og Innovativt Arrangørland Nasjonal Arrangementsstrategi 2020–2030. Available online: https://assets.simpleviewcms.com/simpleview/image/upload/v1/clients/norway/INNO0125_Strategi_Brosjyre_A4_Dobbel_24fe69cc-0a27-40b4-8e40-e0b21f967bff.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- GUS. Culture in 2019, Statistical information, GUS, Warszawa-Kraków 2020. Available online: https://www.kulturradet.no/english/vis/-/covid19-menon (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Qiu, W.; Rutherford, S.; Mao, A.; Chu, C. The Pandemic and its Impacts. Health Cult. Soc. 2017, 9, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentschler, R.; Lee, B. Covid-19 and Arts Festivals: Whither Transformation? J. Arts Cult. Manag. 2021, 14, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, M.; O’Connor, J. A plague upon your howling: Art and culture in the viral emergency. Cult. Trends 2021, 30, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madray, J.S. The Impact Of Covid-19 On Event Management Industry. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 5, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.; Luck, S.; Verner, E. Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu. 2020. Available online: https://www.saudedafamilia.org/coronavirus/artigos/pandemics_depress_economy.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.L.; Hansen, E.T.; Johannesen, N.; Sheridan, A. Pandemic, shutdow and consumer spending: Lessons from scandinavian policy responses to COVID-19. arXiv Prepr. 2020, arXiv:2005.04630. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.04630.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Lin, P.Z.; Meissner, C.M. Health vs. Wealth? Public Health Policies and the Economy During COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27099/w27099.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Lokshin, M.; Torre, I. The sooner, the better: The early economic impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions during the covid-19 pandemic. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 9257. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33820 (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Palrão, T.; Rodrigues, R.I.; Estêvão, J.V. The role of the public sector in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: The case of Portuguese events’ industry. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2021, 22, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, S.S.-A. I am not a party planner!: Setting a baseline for event planners’ professional identity construction before and during COVID-19. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 4, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowen, I. The transformational festival as a subversive toolbox for a transformed tourism: Lessons from Burning Man for a COVID-19 world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhiainen, J.S. Entrepreneurship and Innovation Events during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The User Preferences of VirBELA Virtual 3D Platform at the SHIFT Event Organized in Finland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrecht, J.; Lundberg, E.; Andersson, T.D.; Mykletun, R.J. 20 years of Nordic event and festival research: A review and future research agenda. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 21, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.D. Examining unauthorized events & gatherings in the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2021, 22, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Gajjar, A.; Parmar, B. The Impact of COVID-19 on Event Management Industry in India. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2020, 20, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblatt, J.; Lee, S. The current and future impacts of the 2007-2009 economic recession on the festival and event industry. Int. J. Festiv. Event Manag. 2012, 3, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Munasinghe, M. COVID-19 and sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 23, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Shulla, K.; Voigt, B.-F.; Cibian, S.; Scandone, G.; Martinez, E.; Nelkovski, F.; Salehi, P. Effects of COVID-19 on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Brief Communication. Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.M. Methods of data collection. In Basic Guidelines for Research; Book Zone Publication: Chittagong, Bangladesh, 2016; pp. 201–276. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M. Secondary Data Analysis: A Method of which the Time Has Come. Qual. Quant. Methods Libr. 2014, 3, 619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Vibchute, K.; Aynalem, F. Legal Research Methods. Teaching Material. Prepared under the Sponsorship of the Justice and Legal System Research Institute. 2009, p. 16. Available online: chilot.wordpress.com (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Nassaji, H. Qualitative and descriptive research: Data type versus data analysis. Lang. Teach. Res. 2015, 19, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colier, D. The comparative method. In Political Science: The State of Discipline II; Finifter, A.W., Ed.; American Political Science Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Dogaru, T.-C. The comparative method for policy studies: The thorny aspects. Holistica 2019, 10, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- The Website of the Norway. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/Koronasituasjonen/tidslinje-koronaviruset/id2692402/ (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Nilsen, A.C.E.; Skarpenes, O. Coping with COVID-19. Dugnad: A case of the moral premise of the Norwegian welfare state. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus Commission Report Myndighetenes Håndtering av Koronapandemien Rapport fra Koronakommisjonen, NOU. 2021, p. 6. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/5d388acc92064389b2a4e1a449c5865e/no/pdfs/nou202120210006000dddpdfs.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Official Website of the Norwegian Government. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/nye-nasjonale-innstramminger/id2776995/ (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Regulation of the Minister of Health of 13 March 2020 on the Declaration of an Epidemic Threat in the Territory of the Republic of Poland. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20200000433 (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Regulation of the Minister of Health of March 20, 2020 on the Declaration of an Epidemic in the Territory of the Republic of Poland. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20200000491 (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- The Act of March 31, 2020 Amending the Act on Special Solutions Related to the Prevention, Prevention and Combating of COVID-19, Other Infectious Diseases and Emergencies Caused by Them, and Certain Other Acts. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20200000568 (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Website of the Republic of Poland, Coronavirus: Information and Recommendations. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/coronavirus (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Regulation of the Council of Ministers of November 6, 2020 Amending the Regulation on the Establishment of Certain Restrictions, Orders and Bans in Connection with the Occurrence of an Epidemic. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20200001972 (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Regulation of the Council of Ministers of March 19, 2021 on Establishing Certain Restrictions, Orders and Bans in Connection with an Epidemic. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20210000512 (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/ (accessed on 3 July 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).