The Effects of Social Networking Services on Tourists’ Intention to Visit Mega-Events during the Riyadh Season: A Theory of Planned Behavior Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

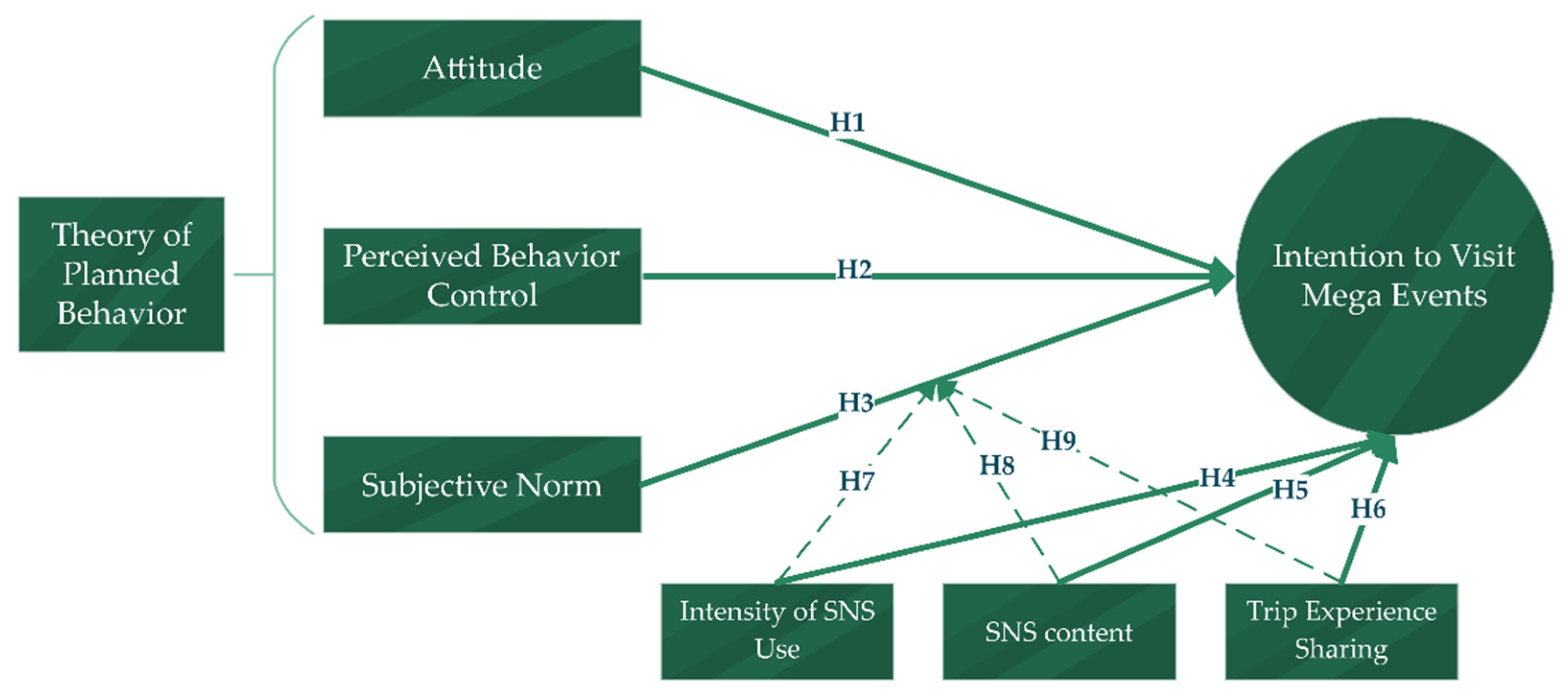

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mega-Events

2.2. The Theory of Planned Behavior

2.3. The Effect of Social Network Services on Individual Intentions and Potential Moderators

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Procedures and the Used Instrument

3.2. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Convergent Validity and Internal Consistency Reliability

4.3. Discriminant Validity

4.4. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, B.; Fyall, A.; Jones, I. The nation branding opportunities provided by a sport mega-event: South Africa and the 2010 FIFA World Cup. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. What makes an event a mega-event? Definitions and sizes. Leis. Stud. 2015, 34, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyikana, S.; Tichaawa, T.M.; Swart, K. Sport, tourism and mega-event impacts on host cities: A case study of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in Port Elizabeth: Tourism. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2014, 20, 548–556. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Milito, M.C.; Nunkoo, R. Residents’ support for a mega-event: The case of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, Natal, Brazil. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, H.H. Conventions as mega-events: A new model for convention-host city relationships. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.K.; Spiegel, M.M. The Olympic Effect. Econ. J. 2011, 121, 652–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Press Agency Riyadh Season Visitors Exceed 11 Million. Available online: https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2329348 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Aldakhil, F.M. Tourist Responses to Tourism Experiences in Saudi Arabia. School of Hospitality and Tourism Management. Master’s Thesis, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Gursoy, D.; Lee, S.-B. The impact of the 2002 World Cup on South Korea: Comparisons of pre- and post-games. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jago, L.; Dwyer, L.; Lipman, G.; van Lill, D.; Vorster, S. Optimising the potential of mega-events: An overview. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2010, 1, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z.K.; Benyoucef, M. Consumer behavior in social commerce: A literature review. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 86, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, P.; Clark, T.; Walker, G. The theory of planned behavior, descriptive norms, and the moderating role of group identification. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 1008–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Hagger, M.S. Mindfulness and the Intention-Behavior Relationship Within the Theory of Planned Behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B. An application of theory of planned behavior to predict young Indian consumers’ green hotel visit intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.; Page, S.J.; Meyer, D. Visitor attractions and events: Responding to seasonality. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, B.M.; Rosentraub, M.S. Hosting mega-events: A guide to the evaluation of development effects in integrated metropolitan regions. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. The mega-event syndrome: Why so much goes wrong in mega-event planning and what to do about it. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2015, 81, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheunkamon, E.; Jomnonkwao, S.; Ratanavaraha, V. Determinant Factors Influencing Thai Tourists’ Intentions to Use Social Media for Travel Planning. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Perceptions of individual behavior in green event—From the theory of planned behavior perspective. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2017, 7, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Potwarka, L.R. Exploring Physical Activity Intention as a Response to the Vancouver Olympics: An Application and Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Event Manag. 2015, 19, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.-K.; Yu, J.-G. Examining the Process Behind the Decision of Sports Fans to Attend Sports Matches at Stadiums Amid the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: The Case of South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Won, D.; Lee, C.; Pack, S.M. Adolescent participation in new sports: Extended theory of planned behavior. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 2246–2252. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, G.B.; Kwon, H. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and Intentions to Attend a Sport Event. Sport Manag. Rev. 2003, 6, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Cheng, M. Communicating mega events on Twitter: Implications for destination marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadis, M.D.; van Zyl, C. Electronic word-of-mouth and online reviews in tourism services: The use of twitter by tourists. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 13, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Priporas, C.-V.; Stylos, N. ‘You will like it!’ using open data to predict tourists’ response to a tourist attraction. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Choi, J.Y.; Koo, C. Effects of ICTs in mega events on national image formation: The case of PyeongChang Winter Olympic Games in South Korea. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2022, 13, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, C.; Stephens, S. The Theory of Planned Behavior: The Social Media Intentions of SMEs. 2019, pp. 1–30. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Simon-Stephens-2/publication/330412288_The_theory_of_planned_behavior_the_social_media_intentions_of_SMEs/links/5c3f056e299bf12be3cb7ab8/The-theory-of-planned-behavior-the-social-media-intentions-of-SMEs.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Shang, Y.; Mehmood, K.; Iftikhar, Y.; Aziz, A.; Tao, X.; Shi, L. Energizing Intention to Visit Rural Destinations: How Social Media Disposition and Social Media Use Boost Tourism Through Information Publicity. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 782461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, Y.; Seok, H.; Nam, Y. The Moderating Effect of Social Media Use on Sustainable Rural Tourism: A Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, H.; Abdurachman, E.; Furinto, A.; Kosasih, W. Social network for the choice of tourist destination: Attitude and behavioral intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 2415–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum Boley, B.; Magnini, V.P.; Tuten, T.L. Social media picture posting and souvenir purchasing behavior: Some initial findings. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narangajavana, Y.; Callarisa Fiol, L.J.; Moliner Tena, M.Á.; Rodríguez Artola, R.M.; Sánchez García, J. The influence of social media in creating expectations. An empirical study for a tourist destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 65, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Davis, W.R. Causal indicator models: Identification, estimation, and testing. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscip. J. 2009, 16, 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Sarstedt, M.; Cheah, J.H.; Ringle, C.M. A concept analysis of methodological research on composite-based structural equation modeling: Bridging PLSPM and GSCA. Behaviormetrika 2020, 47, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D.A.; Judd, C.M. Estimating the nonlinear and interactive effects of latent variables. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 96, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trizano-Hermosilla, I.; Alvarado, J.M. Best alternatives to Cronbach’s alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K. Latent variables and indices: Herman Wold’s basic design and partial least squares. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Vinzi, V., Chin, W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume II, pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Völckner, F. How collinearity affects mixture regression results. Mark. Lett. 2015, 26, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, A.; Fu, X.; Romano, R.; Quintano, M.; Risitano, M. Measuring event experience and its behavioral consequences in the context of a sports mega-event. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 3, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mejías, M.V.; Arroyo-Arcos, L.; Segrado-Pavón, R.G.; De Marez, L.; Ponnet, K. Factors influencing the intention to adopt a pro-environmental behavior by tourist operators of a Mexican national marine park. Tur. Y Soc. 2021, 29, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; King, B.E.M.; Shu, S.-T. Tourist attitudes to mega-event sponsors: Where does patriotism fit? J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hede, A.-M. Sports-events, tourism and destination marketing strategies: An Australian case study of Athens 2004 and its media telecast. J. Sport Tour. 2005, 10, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmaczewska, J.; Czarnecki, R. The Role of a Host Country Image and Mega-Event’s Experience for Revisit Intention: The Case of Poland. Available at SSRN 2586145 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, B.; Fyall, A.; Jones, I. Leveraging nation branding opportunities through sport mega-events. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q. Media Effect on Resident Attitude Toward Hosting the Olympic Games: A Cross-National Study Between China and the USA. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morar, C.; Tiba, A.; Jovanovic, T.; Valjarević, A.; Ripp, M.; Vujičić, M.D.; Stankov, U.; Basarin, B.; Ratković, R.; Popović, M.; et al. Supporting Tourism by Assessing the Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccination for Travel Reasons. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 194 (60.8%) |

| Male | 125 (39.2%) | |

| Age (years) | 20 to <30 | 126 (39.5%) |

| 30 to <40 | 100 (31.3%) | |

| 40 to <50 | 64 (20.1%) | |

| 50 and above | 29 (9.1%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 156 (48.9%) |

| Married | 140 (43.9%) | |

| Other | 23 (7.2%) | |

| Number of children | None | 164 (51.4%) |

| 1 | 34 (10.7%) | |

| 2 | 40 (12.5%) | |

| 3 | 45 (14.1%) | |

| 4 | 31 (9.7%) | |

| 5 above | 5 (1.6%) | |

| Educational level | High School | 48 (15.0%) |

| College | 72 (22.6%) | |

| University | 106 (33.2%) | |

| Graduate school and above | 93 (29.2%) | |

| Monthly income (SAR) | 1000 to <4000 | 77 (24.1%) |

| 4000 to <8000 | 74 (23.2%) | |

| 8000 to <12,000 | 80 (25.1%) | |

| ≥12,000 | 88 (27.6%) |

| Domain | Item | FL | VIF | α | CR | AVE | RhoA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.812 | 0.886 | 0.723 | 0.841 | |||

| ATT_01 | 0.801 | 1.927 | |||||

| ATT_02 | 0.896 | 2.297 | |||||

| ATT_03 | 0.850 | 1.581 | |||||

| PBC | 0.837 | 0.902 | 0.754 | 0.837 | |||

| PBC_01 | 0.880 | 2.128 | |||||

| PBC_02 | 0.865 | 1.917 | |||||

| PBC_03 | 0.859 | 1.874 | |||||

| SNM | 0.786 | 0.875 | 0.701 | 0.787 | |||

| SNM_01 | 0.856 | 1.801 | |||||

| SNM_02 | 0.848 | 1.732 | |||||

| SNM_03 | 0.806 | 1.497 | |||||

| INT | 0.767 | 0.865 | 0.682 | 0.767 | |||

| INT_01 | 0.829 | 1.602 | |||||

| INT_02 | 0.827 | 1.556 | |||||

| INT_03 | 0.822 | 1.529 | |||||

| SNS content × SNM | 1 | 0.872 | 1.036 | 1.115 | 1.000 | ||

| SNS content × SNM_01 | 1.077 | 2.753 | |||||

| SNS content × SNM_02 | 1.076 | 2.601 | |||||

| SNS content × SNM_03 | 1.013 | 1.973 | |||||

| SNS use × SNM | 1 | 0.735 | 0.840 | 0.637 | 1.000 | ||

| SNS use × SNM_01 | 0.767 | 1.533 | |||||

| SNS use × SNM_02 | 0.845 | 1.757 | |||||

| SNS use × SNM_03 | 0.780 | 1.337 | |||||

| TES × SNM | 1 | 0.756 | 0.874 | 0.698 | 1.000 | ||

| TES × SNM_01 | 0.850 | 1.780 | |||||

| TES × SNM_02 | 0.858 | 1.619 | |||||

| TES × SNM_03 | 0.797 | 1.377 |

| Parameter | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ATT | 0.850 | |||||||||

| 2. PBC | 0.502 | 0.868 | ||||||||

| 3. SNM | 0.527 | 0.645 | 0.837 | |||||||

| 4. SNS use | 0.099 | 0.096 | 0.127 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 5. SNS content | 0.289 | 0.384 | 0.412 | −0.015 | 1.000 | |||||

| 6. TES | 0.043 | 0.136 | 0.094 | 0.055 | 0.096 | 1.000 | ||||

| 7. SNS use × SNM | −0.090 | −0.157 | −0.159 | −0.035 | −0.090 | 0.026 | 0.798 | |||

| 8. SNS content × SNM | −0.287 | −0.397 | −0.446 | −0.066 | −0.214 | −0.094 | 0.192 | 1.056 | ||

| 9. TES × SNM | −0.080 | −0.092 | −0.106 | 0.027 | −0.123 | −0.056 | 0.203 | 0.115 | 0.835 | |

| 10. INT | 0.446 | 0.577 | 0.648 | 0.108 | 0.448 | 0.173 | −0.134 | −0.361 | −0.089 | 0.826 |

| Parameter | β | 95%CI | T Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT -> INT (H1) | 0.079 | −0.018 to 0.188 | 1.509 | 0.066 |

| PBC -> INT (H2) | 0.193 | 0.064 to 0.321 | 2.999 | 0.001 |

| SNM -> INT (H3) | 0.376 | 0.248 to 0.509 | 5.795 | <0.0001 |

| SNS use -> INT (H4) | 0.028 | −0.054 to 0.109 | 0.688 | 0.246 |

| SNS content -> INT (H5) | 0.179 | 0.068 to 0.275 | 3.291 | 0.001 |

| TES -> INT (H6) | 0.086 | −0.015 to 0.172 | 1.803 | 0.360 |

| SNM × SNS use -> INT (H7) | −0.015 | −0.116 to 0.078 | −0.319 | 0.625 |

| SNM × SNS content -> INT (H8) | −0.037 | −0.112 to 0.046 | −0.923 | 0.822 |

| SNM × TES -> INT (H9) | 0.009 | −0.104 to 0.111 | 0.158 | 0.437 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Khaldy, D.A.W.; Hassan, T.H.; Abdou, A.H.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Salem, A.E. The Effects of Social Networking Services on Tourists’ Intention to Visit Mega-Events during the Riyadh Season: A Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114481

Al-Khaldy DAW, Hassan TH, Abdou AH, Abdelmoaty MA, Salem AE. The Effects of Social Networking Services on Tourists’ Intention to Visit Mega-Events during the Riyadh Season: A Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114481

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Khaldy, Dayal Ali W., Thowayeb H. Hassan, Ahmed Hassan Abdou, Mostafa A. Abdelmoaty, and Amany E. Salem. 2022. "The Effects of Social Networking Services on Tourists’ Intention to Visit Mega-Events during the Riyadh Season: A Theory of Planned Behavior Model" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114481

APA StyleAl-Khaldy, D. A. W., Hassan, T. H., Abdou, A. H., Abdelmoaty, M. A., & Salem, A. E. (2022). The Effects of Social Networking Services on Tourists’ Intention to Visit Mega-Events during the Riyadh Season: A Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Sustainability, 14(21), 14481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114481