Time Series Modeling Analysis of the Development and Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Spa Tourism in Slovakia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Medical Spa, Wellness and Spa Tourism

2.2. Impact of COVID-19 on Spa Tourism

3. Materials and Methods

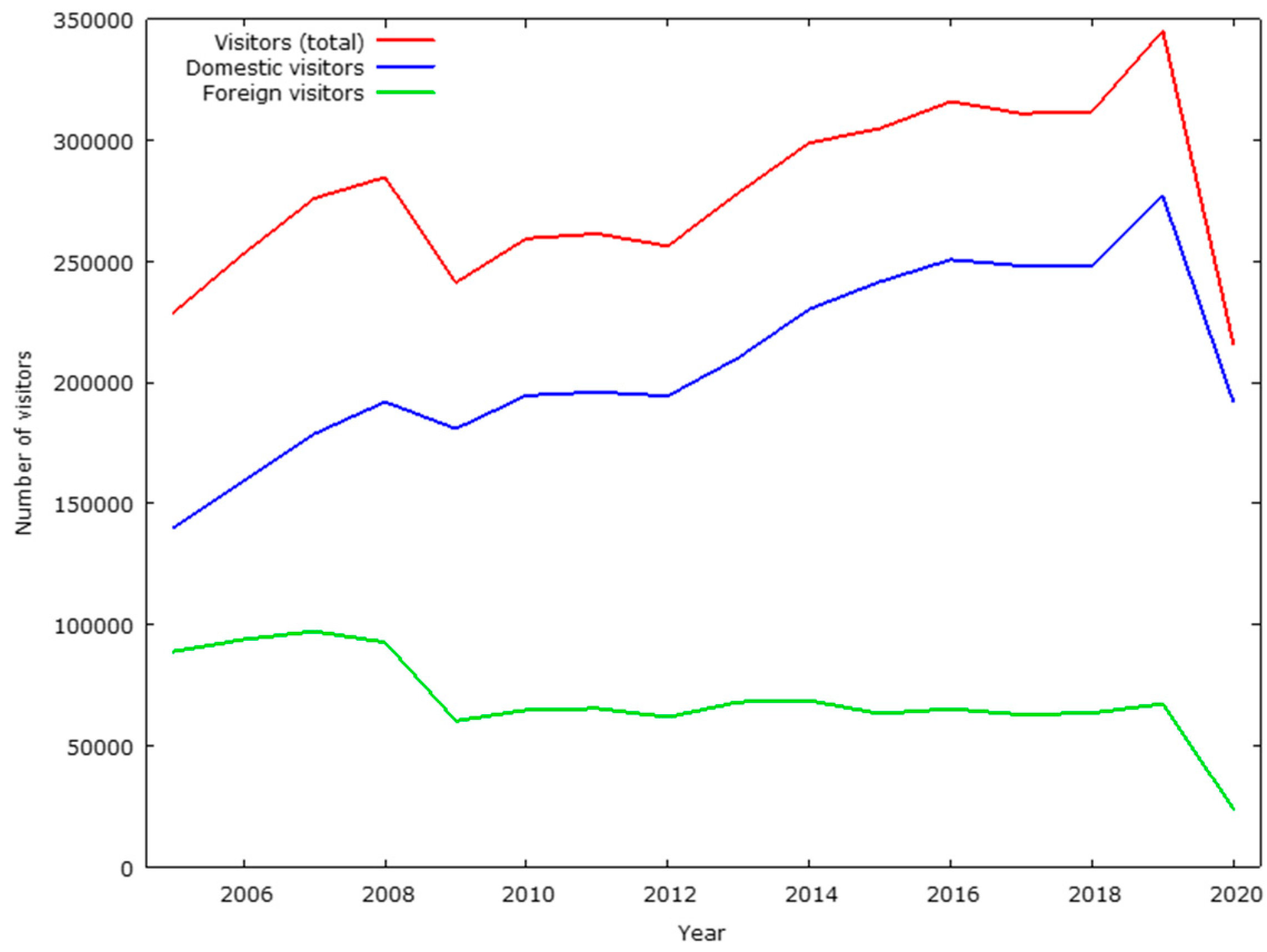

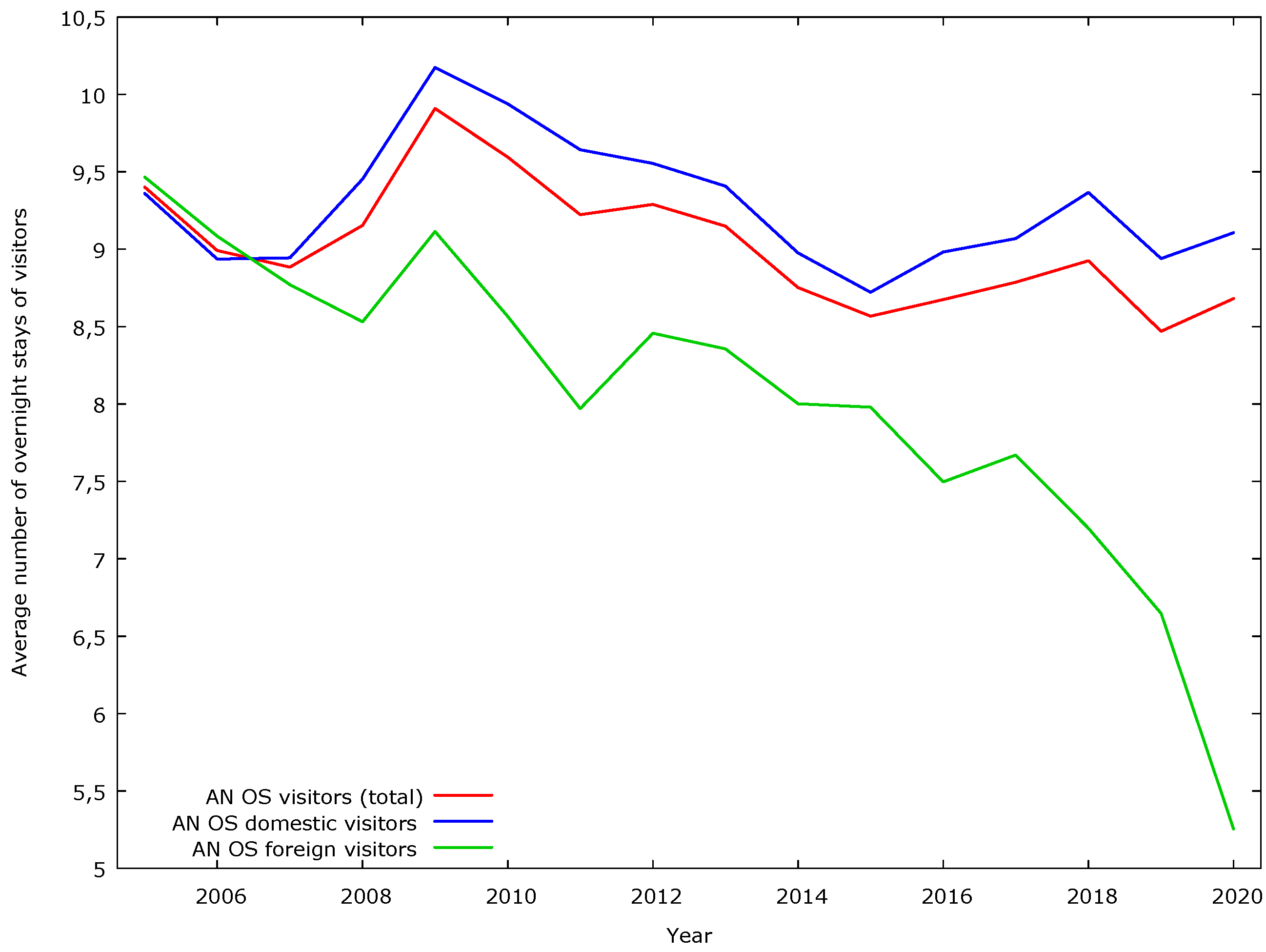

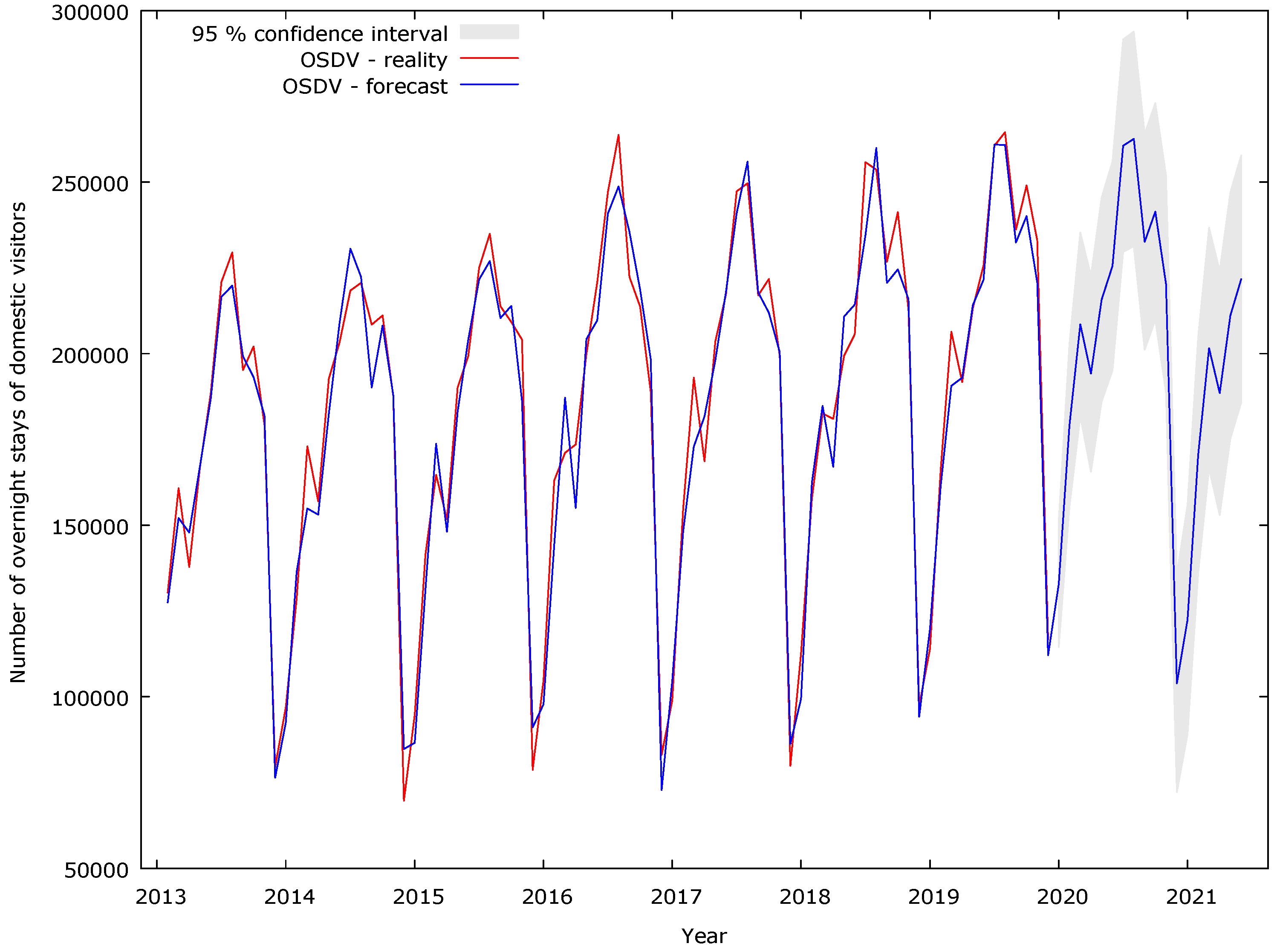

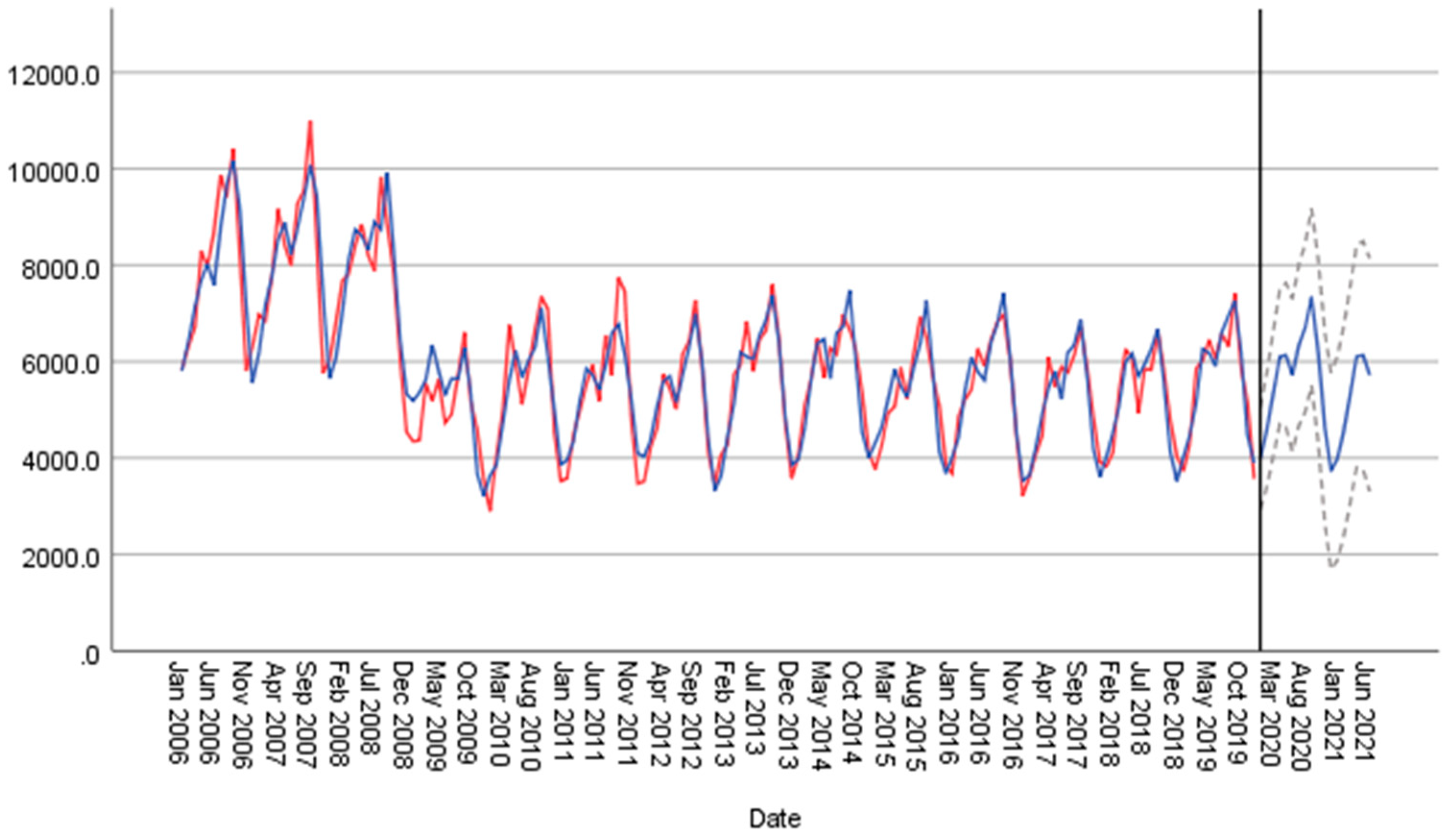

4. Results

4.1. Models of the Development of the Number of Overnight Stays of Domestic and Foreign Spa Tourism Visitors

4.2. Models of the Number of Domestic and Foreign Spa Tourism Visitors

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knopp, K.; Goulli, R.; Mikeš, F. Lázeňství—Ekonomika a Management. [Spa—Economics and Management], 1st ed.; Grada Publishing: Prague, Czechia, 1999; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Plzáková, L.; Crespo Stupková, L. Environment as a Key Factor of Health and Well-Being Tourism Destinations in Five European Countries. IBIMA Bus. Rev. 2019, 611983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Puczkó, L. Health, Tourism and Hospitality; Wellness, Spas and Medical Travel, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Šenková, A.; Mitríková, J. Technológia Kúpeľníckych Služieb. [Technology of Spa Services], 1st ed.; Bookman: Prešov, Slovakia, 2020; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Act on Natural Healing Waters, Natural Curative Spas, Spa Sites and Natural Mineral Waters. No. 538/2005 Coll. Available online: https://www.zakonypreludi.sk/zz/2005-538 (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Eliašová, D. Slovenské Kúpeľníctvo v 20. Storočí. [Slovak Spas in the 20th Century], 1st ed.; Ekonóm: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2009; p. 202. [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the Slovak Republic. Available online: https://korona.gov.sk/en/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Izakova, L.; Breznoscakova, D.; Jandová, K.; Valkucakova, V.; Bezakova, G.; Suvada, J. What mental health experts in Slovakia are learning from COVID-19 pandemic? Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, E. Covid-19 testing in Slovakia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varzaru, A.A.; Bocean, C.G.; Cazacu, M. Rethinking Tourism Industry in Pandemic COVID-19 Period. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasagranda, A.; Gurňák, D. Spa and Wellness Tourism in Slovakia (A Geographical Analysis). Czech J. Tour. 2017, 6, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, M.; Puczkó, L. More than a special interest: Defining and determining the demand for health tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefko, R.; Jenčová, S.; Vašaničová, P. The Slovak Spa Industry and Spa Companies: Financial and Economic Situation. J. Tour. Serv. 2020, 11, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derco, J. Spa tourism in the Slovak Republic. Int. J. Spa Wellness 2020, 3, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derco, J.; Romaniuk, P.; Cehlár, M. Economic Impact of the Health Insurance System on Slovak Medical Spas and Mineral Spring Spas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mainil, T.; Eijgelaar, E.; Klijs, J.; Nawijn, J.; Peeters, P. Research for TRAN Committee—Health Tourism in the EU: A General Investigation; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://doi.org/10.2861/951520 (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Jakubíková, D.; Vildová, E.; Janeček, P.; Tlučhoř, J. Lázeňství, Management a Marketing. [Medical Spa, Management and Marketing], 1st ed.; Grada Publishing: Prague, Czechia, 2019; p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- Mitríková, J.; Sobeková Voľanská, M.; Šenková, A.; Parová, V.; Kaščáková, Z. Bardejov Spa: The analysis of the visit rate in the context of historical periods of its development from 1814 to 2016. Econ. Ann.-XXI 2017, 167, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, M.K.; Dryglas, D. Editorial for the Special Issue of International Journal of Spa and Wellness Challenges for the Spa Sector: Transitioning from Medical to Wellness Services. Int. J. Spa Wellness 2021, 3, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WellSpaV4. The WellSpaV4 Project. Available online: https://www.infota.org/wellspav4konf/index.html#project_desc (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Smith, M.K. WellSpaV4 Project Report. Opportunities and Challenges for V4 Spas. Available online: https://www.infota.org/wellspav4konf/dl/v4-project-report.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Kiráľová, A. Medical Spa and Wellness Spa—Where are they Heading? The Case of the Czech Republic. In Crafting Global Competitive Economies: 2020 Vision Strategic Planning and Smart Implementation, Proceedings of the 24th International Business-Information-Management-Association Conference (IBIMA), Milan, Italy, 6–7 November 2014; Soliman, K.S., Ed.; IBIMA: Norristown, PA, USA; pp. 516–526.

- Vavrečková, E.; Vaníček, J. Význam lázeňství a wellness pro současný cestovní ruch v období změn. [The importance of spa and wellness for today´s tourism in a period of chance]. In Proceedings of the 5th International Colloquium on Tourism, Brno, Czechia, 11–12 September 2014; Holešinská, A., Ed.; Masaryk University: Brno, Czechia, 2014; pp. 92–113. Available online: https://www.econ.muni.cz/do/econ/soubory/katedry/kres/3910085/10619195/sbornik-kolokviumCR2014.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Vavrečková, E.; Stuchlíková, J.; Dluhošová, R. The Results of the Development of Balneal Care Provision and the State of the Czech Spa Industry in Connestion with the Chances in Segislation. Czech J. Tour. 2017, 6, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vystoupil, J.; Šauer, M.; Bobková, M. Spa, Spa Tourism and Wellness Tourism in the Czech Republic. Czech J. Tour. 2017, 6, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gúčik, M.; Kmeco, Ľ.; Kučerová, J.; Malachovský, A.; Maráková, V.; Orieška, J.; Patúš, P.; Raši, Š.; Tomášová, A.; Vetráková, M. Krátky Slovník Cestovného Ruchu. [Short Dictionary of Tourism], 1st ed.; Slovensko-švajčiarske združenie pre rozvoj cestovného ruchu: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2004; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- EuropeSpa. Medical Spa & Wellness. Available online: https://europespa.eu/medical-spa-wellness/medical-wellness/ (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Smith, M.K.; Diekmann, A. Tourism and wellbeing. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derco, J.; Pavlisinová, D. Financial position of medical spas—The case of Slovakia. Tour. Econ. 2016, 23, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litavcová, E.; Jenčová, S.; Košíková, M.; Šenková, A. Implementation of multidimensional analytical methods to compare performance between spa facilities. In Proceedings of the 12th International Days of Statistics and Economics, Prague, Czechia, 6–8 September 2018; Melandrium: Slaný, Czechia, 2018; pp. 1070–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Kučerová, J. Impact of economic crisis on the spa businesses in Slovakia. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Scientific Conference Tourism in Southern and Eastern Europe 2013: Crisis—A Challenge of Sustainable Tourism Development, Opatija, Croatia, 15–18 May 2013; Jankovic, S., Jurdana, D.S., Eds.; University Rijeka, Faculty of Tourism and Hospital Management: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Čabinová, V.; Fedorčíková, R.; Jurová, N. Innovative methods of evaluating business efficiency: A comparative study. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2021, 2, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembošová, M.; Dubcová, A. Prejavy a dôsledky overturizmu v kúpeľnom mieste. [Manifestations and Consequences of Over Turism in a Spa Place]. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference, Jihlava, Czechia, 4–5 March 2020; Linderová, I., Ed.; College of Polytechnics: Jihlava, Czech Republic; pp. 246–255. Available online: https://kcr.vspj.cz/uvod/archiv/konference/aktualni-problemy-cestovniho-ruchu-2020 (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Mitríková, J. Analysis of the attendance of Bardejov Spa Based on the evalution of archived unpublished documents. J. Manag. Bus. 2020, 12, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. International Travel Largely on Hold Despite Uptick in May. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/international-travel-largely-on-hold-despite-uptick-in-may (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Szromek, A.R. The Role of Health Resort Enterprises in Health Prevention during the Epidemic Crisis Caused by COVID-19. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, I. Hungary’s Celebrated Spas on the Brink Because of Coronavirus. Available online: https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2020-10-31/Hungary-s-celebrated-spas-on-the-brink-because-of-coronavirus-V1dpyMyESs/index.html (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Navarrete, A.P.; Shaw, G. Spa tourism opportunities as strategic sector in aiding recovery from Covid-19: The Spanish model. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D. Respiratory rehabilitation for post COVID-19 patients in spa centers: First steps from theory to practice. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1811–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarone, M.C.; Kamioka, H.; Cheleschi, S.; Tenti, S.; Masiero, S.; Kardes, S. Italian and Japanese public attention toward balneotherapy in the COVID-19 era. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardeş, S. Public interest in spa therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analysis of Google Trends data among Turkey. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masiero, S.; Maccarone, M.C.; Magro, G. Balneotherapy and human immune function in the era of COVID-19. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1433–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Moure, O.; Saz-Peiró, P. The role of spas during the COVID-19 crisis. Med. Natur. 2021, 15, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Aluculesei, A.C.; Nistoreanu, P.; Avram, D.; Nistoreanu, B.G. Past and Future Trends in Medical Spas: A Co-Word Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Transformational Wellness Tourism System Model in the Pandemic Era. Int. J. Health Manag. Tour. 2020, 5, 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport and Construction of the Slovak Republic. Kúpeľný cestovný Ruch. Kapacity a Výkony Kúpeľných Ubytovacích Zariadení na SLOVENSKU za Roky 2005–2017. [Spa Tourism. Capacities and Performances of Spa Accommodation Facilities in Slovakia in the Years 2005–2017]. Available online: https://www.mindop.sk/ministerstvo-1/cestovny-ruch-7/statistika/kupelny-cestovny-ruch (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Litavcová, E.; Košíková, M. Predikcia a komparácia priemerných miezd v odvetviach cestovného ruchu so mzdami v iných odvetviach. [Prediction and comparison of average wages in tourism industries with wages in other industries]. In Non-Conference Peer-Reviewed Collection of Scientific Works; Litavcová, E., Popovičová, M., Eds.; Prešov University: Prešov, Slovakia, 2018; pp. 48–61. Available online: https://ezproxy.pulib.sk:2067/web/kniznica/elpub/dokument/Litavcova1 (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Litavcová, E.; Jenčová, S. Analytický Pohľad na Problém Chudoby a Nezamestnanosti v Podmienkach Slovenska. [Analytical View on the Problem of Poverty and Unemployment in the Conditions of Slovakia], 1st ed.; Tribun EU: Brno, Czechia, 2014; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Litavcová, E.; Jenčová, S.; Vašaničová, P. On Modelling the Evolution of Financial Metrics in Decision Making Unit in the Electronics Industries. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Mathematical Methods in Economics, Hradec Králove, Czechia, 13–15 September 2017; Pražák, P., Ed.; University of Hradec Králove: Hradec Králove, Czechia, 2017; pp. 408–413. [Google Scholar]

- Vašaničová, P. Vývoj indexu tržieb za ubytovacie a stravovacie služby. [Development of the index of sales for accommodation and food services]. In Predikčná Analýza Finančnej Situácie Nefinančných Korporácií. [Predictive Analysis of the Financial Situation of Non-Financial Corporations]; Bookman: Prešov, Slovakia, 2019; pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Litavcová, E.; Jenčová, S. Štatistické modely vo finančnom riadení firmy. [Statistical models in the financial management of the company]. Finančné trhy [Financ. Mark.] 2014, 4, 1336–5711. Available online: http://www.derivat.sk/files/2014%20financne%20trhy/Okt_2014_FT_Statis_Modely_Litavcova_Jencova.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2014).

- Saayman, A.; Botha, I. Non-linear models for tourism demand forecasting. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 594–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondaca-Marino, C.; Arriagada-Milaman, A.; Montecinos-Astorga, A.; Colther-Marino, C. Modelamiento y pronóstico de la demanda turística a nivel regional en chile: Un análisis con modelos SARIMA. Turismo 2020, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Ji, L.; Wu, C.W.D.; Tso, K.F.G. Using SARIMA-CNN_LSTM approach to forecast daily tourism demand. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.C.W.; Ji, L.; He, K.; Tso, K.F.G. Forecasting tourist daily arrivals with a hybrid Sarima-Lstm approach. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 45, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiráľová, A.; Straka, I. Vliv Globalizace na Marketing Destinace Cestovního Ruchu. [The Impact of Globalization on Tourism Destination Marketing], 1st ed.; Ekopress: Prague, Czechia, 2013; p. 228. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | Z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| phi_1 | 0.8162 | 0.0506 | 16.1300 | 0.0000 |

| Theta_1 | −0.5289 | 0.0803 | −6.5850 | 0.0000 |

| Schwarz criterion (SBC) | 3317.0310 | |||

| Akaike criterion (AIC) | 3307.8820 | |||

| Hannan–Quinn criterion (HQC) | 3311.5980 | |||

| MAPE | 5.1707 | |||

| Theil’s U | 0.2833 | |||

| Normality of residual | Chi-square test = 0.5760 | 0.7496 | ||

| Autocorrelation | Ljung-Box Q’ = 16.3424 | 0.0902 | ||

| Period | Prediction | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval | Reality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCI | UCI | ||||

| 2020/January | 132,889 | 9,397.316 | 114,470.09 | 151,306.89 | |

| 2020/February | 132,888 | 12,130.285 | 155,234.44 | 202,784.28 | |

| 2020/March | 208,581 | 13,650.673 | 181,826.5 | 235,336.16 | |

| 451,531.03 | 589,427.33 | 424,290 | |||

| 2020/April | 194,148 | 14,575.837 | 165,580.26 | 222,716.5 | |

| 2020/May | 215,746 | 15,160.904 | 186,031.01 | 245,460.66 | |

| 2020/June | 225,542 | 15,538.469 | 195,087.25 | 255,996.93 | |

| 546,698.52 | 724,174.09 | 218,524 | |||

| 2020/July | 260,596.4 | 15,785.002 | 229,658.35 | 291,534.42 | |

| 2020/August | 262,577.3 | 15,947.133 | 231,321.51 | 293,833.13 | |

| 2020/September | 232,589.8 | 16,054.241 | 201,124.1 | 264,055.57 | |

| 662,103.96 | 849,423.12 | 763,905 | |||

| 2020/October | 241,416.8 | 16,125.205 | 209,811.99 | 273,021.63 | |

| 2020/November | 220,301.3 | 16,172.31 | 188,604.14 | 251,998.43 | |

| 2020/December | 103,916.3 | 16,203.616 | 72,157.82 | 135,674.83 | |

| 470,573.95 | 660,694.89 | 341,236 | |||

| 2021/January | 122,477.8 | 17,032.411 | 89,094.86 | 155,860.68 | |

| 2021/February | 170,511.8 | 17,562.883 | 136,089.22 | 204,934.45 | |

| 2021/March | 201,645.4 | 17,907.578 | 166,547.21 | 236,743.62 | |

| 391,731.29 | 597,538.75 | 172,053 | |||

| 2021/April | 188,487.1 | 18,133.587 | 152,945.92 | 224,028.27 | |

| 2021/May | 211,124.9 | 18,282.609 | 175,291.68 | 246,958.19 | |

| 2021/June | 221,770.4 | 18,381.222 | 185,743.85 | 257,796.92 | |

| 513,981.45 | 728,783.38 | 445,586 | |||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | Z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| phi_1 | −0.5275 | 0.0687 | −7.674 | 0.0000 |

| Theta_1 | −0.4594 | 0.0777 | −5.9110 | 0.0000 |

| Schwarz criterion (SBC) | 3079.9770 | |||

| Akaike criterion (AIC) | 3070.8470 | |||

| Hannan–Quinn criterion (HQC) | 3074.555 | |||

| MAPE | 8.2448 | |||

| Theil’s U | 0.4695 | |||

| Normality of residual | Chi-square test = 35.5050 | 0.0000 | ||

| Autocorrelation | Ljung-Box Q’ = 21.7234 | 0.01658 | ||

| Alpha (Level) | Gamma (Trend) | Delta (Season) | MAPE | BIC | Autocorrelation of Residues | RS2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ljung-Box Q’ | Sign. | ||||||

| 0.3020 | 0.0010 | 0.1630 | 5.380 | 14.332 | 25.031 | 0.0510 | 0.517 |

| Period | Prediction | 95% Confidence Interval | Reality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCI | UCI | |||

| 2020/January | 17,203.7 | 14,762.3 | 19,645.1 | |

| 2020/February | 24,494.0 | 21,836.7 | 27,151.2 | |

| 2020/March | 25,460.3 | 22,679.4 | 28,241.3 | |

| 67,158.0 | 59,278.4 | 75,037.7 | 50,129 | |

| 2020/April | 25,261.6 | 22,391.7 | 28,131.5 | |

| 2020/May | 26,443.9 | 23,436.7 | 29,451.2 | |

| 2020/June | 26,665.5 | 23,560.7 | 29,770.4 | |

| 78,371.1 | 69,389.1 | 87,353.1 | 21,115 | |

| 2020/July | 32,333.3 | 28,846.8 | 35,819.9 | |

| 2020/August | 32,512.7 | 28,940.7 | 36,084.7 | |

| 2020/September | 27,891.6 | 24,522.3 | 31,260.8 | |

| 92,737.6 | 82,309.7 | 103,165.5 | 91,528 | |

| 2020/October | 28,293.9 | 24,821.9 | 31,765.8 | |

| 2020/November | 27,322.0 | 23,838.3 | 30,805.7 | |

| 2020/December | 14,437.8 | 11,639.1 | 17,236.5 | |

| 70,053.6 | 60,299.3 | 79,808.0 | 29,168 | |

| 2021/January | 17,658.1 | 14,486.7 | 20,829.5 | |

| 2021/February | 25,139.4 | 21,286.5 | 28,992.3 | |

| 2021/March | 26,129.8 | 22,119.2 | 30,140.4 | |

| 68,927.3 | 57,892.4 | 79,962.3 | 15,678 | |

| 2021/April | 25,924.4 | 21,868.9 | 29,979.9 | |

| 2021/May | 27,136.2 | 22,896.7 | 31,375.8 | |

| 2021/June | 27,362.1 | 23,038.7 | 31,685.5 | |

| 80,422.8 | 67,804.3 | 93,041.2 | 49,718 | |

| Alpha (Level) | Delta (Season) | MAPE | BIC | Autocorrelation of Residues | RS2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ljung-Box Q’ | Sign. | |||||

| 0.5000 | 0.0000 | 7.4910 | 12.627 | 22.014 | 0.1430 | 0.6120 |

| Period | Prediction | 95% Confidence Interval | Reality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCI | UCI | |||

| 2020/January | 3982.7 | 2925.6 | 5039.8 | |

| 2020/February | 4574 | 3392.3 | 5755.7 | |

| 2020/March | 5337.1 | 4042.8 | 6631.4 | |

| 13,893.8 | 10,360.7 | 17,426.9 | 9762 | |

| 2020/April | 6102.5 | 4704.6 | 7500.4 | |

| 2020/May | 6137.1 | 4642.8 | 7631.5 | |

| 2020/June | 5724.5 | 4139.6 | 7309.4 | |

| 17,964.1 | 13,487 | 22,441.3 | 1572 | |

| 2020/July | 6356.5 | 4685.9 | 8027.1 | |

| 2020/August | 6714.6 | 4962.5 | 8466.6 | |

| 2020/September | 7342.6 | 5512.7 | 9172.5 | |

| 20,413.7 | 15,161.1 | 25,666.2 | 11,597 | |

| 2020/October | 6234.4 | 4329.8 | 8139 | |

| 2020/November | 4649.3 | 2672.8 | 6625.8 | |

| 2020/December | 3729.3 | 1683.5 | 5775.1 | |

| 14613 | 8686.1 | 20,539.9 | 938 | |

| 2021/January | 3982.7 | 1869.8 | 6095.6 | |

| 2021/February | 4574 | 2396.1 | 6751.9 | |

| 2021/March | 5337.1 | 3096.1 | 7578.1 | |

| 13,893.8 | 7362 | 20,425.6 | 872 | |

| 2021/April | 6102.5 | 3800.1 | 8404.9 | |

| 2021/May | 6137.1 | 3775 | 8499.3 | |

| 2021/June | 5724.5 | 3304 | 8145 | |

| 17,964.1 | 10,879.1 | 25,049.2 | 2290 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Šenková, A.; Košíková, M.; Matušíková, D.; Šambronská, K.; Kravčáková Vozárová, I.; Kotulič, R. Time Series Modeling Analysis of the Development and Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Spa Tourism in Slovakia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011476

Šenková A, Košíková M, Matušíková D, Šambronská K, Kravčáková Vozárová I, Kotulič R. Time Series Modeling Analysis of the Development and Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Spa Tourism in Slovakia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(20):11476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011476

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠenková, Anna, Martina Košíková, Daniela Matušíková, Kristína Šambronská, Ivana Kravčáková Vozárová, and Rastislav Kotulič. 2021. "Time Series Modeling Analysis of the Development and Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Spa Tourism in Slovakia" Sustainability 13, no. 20: 11476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011476

APA StyleŠenková, A., Košíková, M., Matušíková, D., Šambronská, K., Kravčáková Vozárová, I., & Kotulič, R. (2021). Time Series Modeling Analysis of the Development and Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Spa Tourism in Slovakia. Sustainability, 13(20), 11476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011476