Abstract

This study aimed to find the role of image congruence in the context of robotic coffee shops. More specifically, this study proposed that three types of image congruence including actual self-image congruence, ideal self-image congruence, and social self-image congruence aid to increase brand attitude. In addition, it was proposed that brand attitude positively affects brand attachment and brand loyalty. For this, this study collected data from 325 customers who used robotic coffee shops. The data analysis results indicated that the three types of image congruence have a positive influence on brand attitude. In addition, brand attitude was found to be an important factor affecting brand attachment and brand loyalty.

1. Introduction

Recently, the impact of COVID-19 has led to an increase in the use of technological innovations in order to offer contactless services and enhanced take-out options, which help to reduce the risk of COVID-19 [1,2,3,4]. The coffee industry is no exception. For instance, Starbucks in the United States plans to increase the number of drive-throughs, offer curbside pickup by creating larger parking lots, increase grab-and-go stores, and encourage pre-ordering via digital applications to reduce the amount of time spent inside a store [5]. Shim et al. [6] found that quarantine was an indicator of consumers’ purchase intention in the coffee industry, indicating a desire for contact-free services. More importantly, the role of robots has attracted attention in the coffee industry [7,8]. For example, according to Robotics Tomorrow [9], Briggo is a robot barista that is in the form of a brewing vending machine, Café X is a robot barista that has a six-axis robotic arm and resembles an aquarium, and Rozum Café is a robot that has a pulse robot coffee arm. In Singapore, a coffee shop has employed a robot barista, Ella, a robot barista who takes orders through an application and can make up to 200 coffee beverages in an hour [10]. Such robot baristas have the potential to help businesses cut down on labor costs and more importantly can offer contactless services, which are sought after in the pandemic era [11].

As robot baristas are a new emergence, in order to assess how well consumers accept and adapt to them, it is crucial to examine the reasons customers choose to visit relevant coffee shops. It is widely known that consumers tend to choose products, or in this case baristas, that reflect images and personality attributes congruent to the self-image of themselves [12]. That is, consumers believe that purchasing a certain product or using a particular service allows them to maintain a desired self-image [13]. Although prior studies have tried to deal with diverse topics in the coffee industry, there are few studies related to robotic coffee baristas. In particular, despite the importance of image congruence in the field of robotic coffee shops, no research has examined its role in the coffee shop industry.

Therefore, to fill this gap, the purpose of this study is to explore the importance of image congruence in the context of robotic coffee shops. More specifically, this study examined the effect of three sub-dimensions of image congruence including actual, ideal, and social self-image congruence on brand attitude. In addition, this study investigated how brand attitude affects brand attachment and brand loyalty. Lastly, this study explored the relationship between brand attachment and brand loyalty. The results of this study are expected to have important practical implications in providing useful information to managers preparing for robot coffee shops, and significant theoretical implications by applying the concept of image congruence to this new field for the first time.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Explanation of Each Concept

2.1.1. Image Congruence

Image congruence refers to the idea that consumers choose products or services that are consistent to their own self-image [12]. Just as people, products and services have personality images that are not determined by the physical setting, but by a set of attributes impacted by marketing and psychological associations [13]. The self-congruity theory explains that image congruence impacts consumer behavior in that consumers make a psychological connection between the image of a service or product and their own self-concept [14]. An individual may use a product or service to maintain or even improve one’s image. This concept can be observed across many industries, including the coffee shop industry. For instance, an average cup of coffee in a name-brand coffee shop in South Korea costs approximately $5.19, yet consumers are still willing to pay a high price for a cup of coffee because name-brand coffee shops reflect an image of Western culture and a trendy lifestyle [15]. In the study of Sirgy [13], image congruence was defined as having four major components, including actual self-image, ideal self-image, social self-image, and ideal social self-image. For the purpose of this research, actual self-image congruence, ideal self-image congruence, and social self-image congruence were assessed.

Actual self-image is defined as how a person actually sees one’s self [12]. Previous studies have found that there is a significant relationship between actual self-image and consumer choice [16]. For example, an individual may view themselves as a trendy and technologically savvy person and will likely choose brands that are also viewed as being up to date with new trends and technological services, including robot baristas. Ideal self-image is defined as the image a person would like to see about him or herself [12]. Particularly, ideal self-image is how consumers would like to view themselves in reference to the personality of the brand [17]. This type of person may not view themselves as trendy or up to date with new technology currently, but they feel that by using certain products or brands that appear as trendy, then they can see that same image in him or herself. Social self-image is defined as how a person thinks other people view him or herself [18]. An example of social self-image would be if a person is not necessarily wealthy, but purchases a product or uses a service from a brand that is known for being expensive, then others may view the individual as successful and wealthy.

According to the study of Sirgy et al. [14], the self-consistency motive represents the idea that people tend to behave in certain ways to maintain their self-image. Self-consistency motives stop people from engaging in certain behaviors that are inconsistent with their self-concept [17]. In regards to the self-consistency motive, actual self-image congruency and social self-image congruency are included because in these contexts the behavior is based on self-perception and maintaining one’s self-image [15]. In contrast, the self-esteem motive describes the behavior of individuals to enhance one’s self-image [16]. As opposed to self-consistency motives, self-esteem motives help people strive for a more unique self-image [17]. If a consumer feels the image of the brand and their ideal self-image are alike, their needs for self-esteem will most likely be satisfied [19]. Ideal self-image congruency can be explained by the self-esteem motive ideal because it is assumed that individuals will strive to enhance their self-image and self-esteem based on how others view them [15]. Consumers have a tendency to use brands that reflect their self-concept [20]. Considering image congruence is an essential factor in deciding how consumers behave; this study aimed to explore the relationship between self-image congruency and brand attitude, brand attachment, and brand loyalty pertaining to the context of robot coffee shops.

2.1.2. Brand Attitude

Brand attitude can be described as the consumers’ overall assessment of a brand [21,22,23,24]. Furthermore, brand attitude includes the feelings a consumer has towards a brand [15,25]. Brand attitudes are also used as a measurement tool to assess how strong of a relationship the consumer has with the brand [26]. A consumer’s attitude toward a particular brand is formed based on the experience with the brand and image congruence was found to have a great impact in creating a positive emotional experience [27]. Bajac et al. [20] concluded that if a consumer considers themselves similar to the brand, they are more likely to develop positive attitudes. Back [12] found that image congruence has a positive influence on consumers’ brand attitude and brand loyalty in a hotel context. Brand attitude plays such a significant role in the success of a company that it has been studied across various industries. Sirgy et al. [14] found that image congruence had a strong impact on brand attitude in a travel destination context. Hwang, Lee, and Kim [28] found that perceived innovativeness positively affect attitude in the context of drone food delivery services, and Hwang and Lee [29] confirmed brand attitude has a positive impact on brand attachment and brand loyalty in the senior tourist industry. In the coffee industry, Kang et al. [15] found that the symbolic store image played a significant role in brand attitude in the context of name-brand coffee shops. Brand attitude also affects many other concepts, and in the next section, the impact on brand attachment is discussed.

2.1.3. Brand Attachment

Brand attachment is described as the relationship or strength of a bond that a consumer and brand have [23]. This idea can be confirmed by the attachment theory, which is a psychological theory that refers to the idea that humans naturally form bonds with a person or object, in this case a brand, as an effort to console themselves [30]. In reference to image congruence, consumers most often connect the image of the brand to their own image, and then in turn will develop a solid bond with the brand [31]. Moreover, consumers who have positive experiences and memories of using a brand are more likely to have positive feelings towards the relationship between oneself and the brand [23]. A strong brand attachment bond will help fulfill the emotional needs of the consumer, enabling them to console themselves when using the brand [23]. If consumers can relate their own self-image to the image of a robot coffee shop and are satisfied with the way others view them while using a robot coffee shop, they will develop a strong brand attachment. For example, considering robot coffee shops are just emerging for the first time in many cases, many people may not have experience ordering coffee from a robot barista, and some may even hesitate if they are not familiar with using high advanced technological services. Using a robot coffee shop may reflect the image that the consumer is not afraid to try new things, keeps up or stays ahead of current trends, and has the ability to use high advanced technology. If the consumer matches the image of the robot coffee shop to their self-image, then they will have stronger attachment to the brand.

2.1.4. Brand Loyalty

Brand loyalty refers to the idea that a consumer consistently and repeatedly visits a certain brand over a period of time [12,32]. Brand loyalty is more than just revisiting or repurchasing, brand loyalty occurs when the consumer develops a psychological dedication that lasts for an extended duration [33]. Loyal customers are particularly important to a brand because they are generally willing to pay a high price for a product or service, have great knowledge about the brand, which may help reduce marketing costs, and they are less likely to switch to another brand [34]. Loyal consumers view the relationship between themselves and a brand as a partnership, and are strongly committed to maintaining the relationship [35]. If consumers perceive his or her personality similar to the personality of the brand, then they are more likely to develop loyalty toward the brand [19]. In regards to the significance of image congruence on brand loyalty, previous studies have shown that image congruence is a positive function of store loyalty [36]. Furthermore, Sirgy et al. [13] discovered that image congruence is a significant factor in the formation of brand loyalty. Nienstedt et al. [19] found that image congruence, both ideal and actual, had an impact on brand loyalty in the context of print and online magazines. In the study of Back [12], the results supported the notion that when consumers held an image of a person closely to the image of a hotel brand, the consumer had higher customer satisfaction and in turn became loyal to the hotel brand. Han and Back [31] also concluded that image congruence has a significantly positive impact on brand loyalty when consumers have a perception that their self-image and brand image are similar. In this study, the same idea is assumed in the context of robot coffee shops. Products that are consumed publicly have an impact particularly on consumers’ social self-image congruence, which in turn can lead to becoming loyal to the brand [31]. This can apply to the context of robot coffee shops as the products are consumed in public. Consumers who perceive positive images of robot coffee shops will continue patronage to the shop.

2.2. Hypotheses Development

Consumers exhibit a preference for a brand that reflects a personality consistent with their image [37]. Likewise, prior studies have documented that self-image congruence is a definite indicator of brand attitude [12,14,27,38,39]. Liu, Mizerski, and Soh [40] explored self-image congruence in order to understand the consumption behavior of luxury fashion brands, finding that user and usage imagery congruity exert a significant influence on brand attitude. They accordingly asserted that promoting symbolic benefits are crucial for luxury brands. Abosag et al. [17] discovered that consumers who have image congruence with a brand are capable of becoming satisfied with the brand’s social networking site as well. Kang et al. [15] investigated the antecedents of customer behavior in coffee shops through the lens of self-congruence theory and their analysis showed a strong relationship between self-congruity and customer attitude. Similarly, Zhu et al. [39] adopted the self-congruence theory to explain consumption behavior, which focused on Chinese consumers related to the brand type and celebrity endorser type. Their findings determined how actual self-congruity and ideal self-congruity have a different impact on brand attitude according to functional and symbolic brands that originated from Western countries and Western versus Chinese celebrity endorsements. In service innovations, image congruence has been also validated as an important construct in creating customers’ positive evaluation toward a brand. For example, Kleijnen et al. [37] confirmed that image congruence plays a prime role in forming consumer attitude in the adoption of innovative technology. Bennett and Vijaygopal [41] posited that the consumer self-image congruity contributes to a favorable attitude towards electronic vehicles, and the analysis results accord closely with their prediction. These previous findings indicate the clear connection between self-image congruence and brand attitude, and support the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Actual self-image congruence has a positive effect on brand attitude.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Ideal self-image congruence has a positive effect on brand attitude.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Social self-image congruence has a positive effect on brand attitude.

Current academic evidence suggests that brand attitude increases the emotional bond with a brand across different contexts [29]. Han et al. [27] provided empirical evidence of the link between attitude and repeat patronage intention in the airline sector. Yu [42] assessed the effect of attitude on brand-self connection and its consequences in the lodging industry, confirming the salient role of attitude in the retention strategy through building a bond with a brand. In addition, the existing studies denote that brand attitude cultivates loyalty to a specific brand [40,41,43]. For instance, Bozbay, Karami, and Arghashi [44] examined the antecedents of users’ brand loyalty toward social media, and their findings indicated that brand attitude helps shape brand loyalty. Oh, Yoo, and Lee [45] demonstrated that consumers’ brand attitude positively affected brand loyalty toward a branded coffee shop, and they contended that building a positive attitude is indispensable to develop a sustainable advantage in the competitive coffee shop business. These studies suggest that the role of brand attitude becomes apparent in predicting brand attachment and brand loyalty. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Brand attitude has a positive effect on brand attachment.

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

Brand attitude has a positive effect on brand loyalty.

Brand attachment is one of the essential predictors of brand loyalty through increased intentions to buy, positive word-of-mouth, and willingness to pay premium. As an example, Bahri-Ammari et al. [46] studied the formation of behavioral loyalty in the luxury restaurant setting, and their study observed that brand attachment affects the intention to continue the relationship. Yu [42] underpinned the significant role of brand-self connection in shaping hotel customers’ repeat visit intentions. The same findings exist for the coffee shop industry [47,48]. For instance, Jang [49] asserted the importance of green spaces in coffee shops through the analysis results, which confirmed that customers’ emotional bond stemming from the green servicescape of coffee shops increases loyalty. Hence, the close relationship between brand attachment and brand loyalty was hypothesized.

Hypothesis 6 (H6):

Brand attachment has a positive effect on brand loyalty.

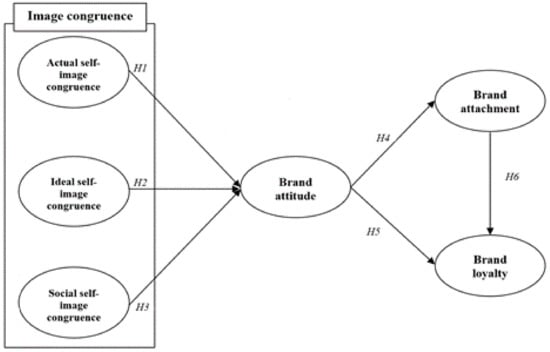

Based on the literature review, a conceptual model was developed, as shown in Figure 1. The proposed conceptual model shows the variables that were assessed in the robot coffee shop context, the relationships among the variables, and the hypotheses tested in this study. First, image congruence consisted of actual self-image, ideal self-image, and social self-image. The impact of image congruence on brand attitude, brand attachment, and brand loyalty was explored. In order to achieve the purposes of this study, the six aforementioned hypotheses were formed and analyzed.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures

Validated measures in the literature were adapted to the context of robotic coffee shops with varying degrees of modifications. A total of six constructs were used in the conceptual model for this study. Image congruence consisted of three sub-dimensions, including actual self-image congruence, ideal self-image congruence, and social self-image congruence, and they were measured with nine items adapted from Han and Hyun [18], He and Mukherjee, 2007 [50], and Hosany and Martin [51]. Measures, including three items for brand attitude, were borrowed from Hwang, Lee, and Kim [28], Mitchell and Olson [52], and Kim and Hwang [53]. Brand attachment was measured with three items employed by Carroll and Ahuvia [54] and Hwang and Lee [29]. Measures with three items for brand loyalty were cited from Hennig-Thurau, Gwinner, and Gremler [55] and Zeithaml, Berry, and Parasuraman [56].

3.2. Data Collection

This study conducted an in-person survey at a robot coffee shop because there are very few robot coffee shops in Korea. The robot barista is able to make up to 14 cups of coffee at the same time, and has the ability to make 90 cups of coffee in an hour. In this particular robot coffee shop, no human employees are present. D brand, which is a South Korean coffee brand, was chosen for this study due to the fact that this brand operates robot barista coffee shops (see Appendix A and Appendix B). The robot barista coffee shop observed in this study consisted of a booth where the robot barista takes customers’ orders using their smartphone. After taking the customer’s order, the robot barista makes the beverage. Customers receive coffee after entering the password sent to their smartphones into the coffee machine. More importantly, customers can place their order ahead of time through a smartphone application, which can reduce the amount of time customers spend waiting for the beverage to be made.

In order to conduct the in-person survey effectively and efficiently, a widely known Korean surveying company, M company, was selected to administer the surveying process. The surveyors were provided with necessary education and training by M company. A total of 10 surveyors stood near the entrance of the coffee shop, conducting face-to-face interviews with customers who actually purchased a beverage and received service from the robot barista. Respondents were provided a complete explanation of the purpose of the study before starting the interview. Lastly, after the survey was completed, a certain product was provided to the respondents. A total of 339 questionnaires were collected. After performing a visual inspection and Mahalanobis distance check, 14 questionnaires were excluded, leaving 325 questionnaires for analyses.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows the respondents’ demographic profile. Of the total 325, 136 were males (41.8%) and 189 were females (58.2%). In addition, the mean age was 35.46 years of age. In terms of monthly household income, 24.6% of the respondents (n = 80) reported that they earned between USD 5001 and USD 6000. More than half of the respondents were single (n = 169, 51.4%). Lastly, 62.2% (n = 202) held a bachelor’s degree.

Table 1.

Profile of survey respondents (n = 325).

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

This study performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in order to check the appropriateness of the measurement structure. CFA results revealed that the model had appropriate fit statistics (χ2 = 248.530, df = 120, χ2/df = 2.071, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.952, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.967, and RMSEA = 0.057). The factor loadings, as shown in Table 2, were equal to or greater than 0.722, and all factor loadings were significant at p < 0.001.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis items and loadings.

In addition, as shown in Table 3, the composite reliabilities of constructs were greater than 0.70, ranging from 0.858 to 0.938, suggesting that all constructs in the model have satisfactory internal consistency [57]. All average variance extracted (AVE) estimates ranging from 0.671 to 0.835 were higher than 0.05, which is the recommended threshold value [58], indicating that convergent validity was supported. Lastly, as suggested by Fornell and Larcker [58], discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the AVE values with the squared correlation for each pair of constructs. The results showed that the discriminant validity of study variables was evident in that AVE values were higher than the values of the squared correlations.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and associated measures.

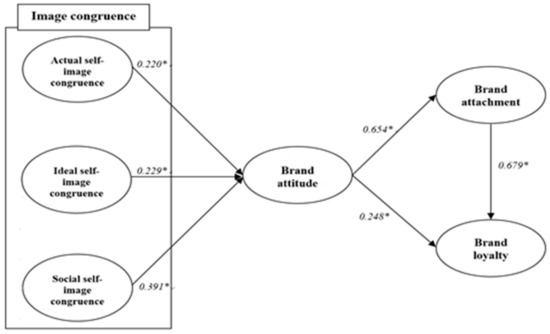

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling

The structural model was assessed to validate the proposed associations among study constructs. The results of the structural equation modeling (SEM) showed an appropriate fit of the model, demonstrating the soundness of the conceptual model and providing a good basis for testing the proposed links (χ2 = 294.405, df = 126, χ2/df = 2.337, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.943, CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.959, and RMSEA = 0.064). Figure 2 presents the SEM results with standardized coefficients. Of the six proposed hypotheses, six were statistically supported at p < 0.05. More specifically, actual self-image congruence (β = 0.220, p < 0.05), ideal self-image congruence (β = 0.229, p < 0.05), and social self-image congruence (β = 0.391, p < 0.05) help to enhance brand attitude. That is, social self-image congruence had the greatest influence on brand attitude. In addition, brand attitude positively affects brand attachment (β = 0.654, p < 0.05) and brand loyalty (β = 0.248, p < 0.05). Lastly, there is a positive relationship between brand attachment and brand loyalty (β = 0.679, p < 0.05). Table 4 provides a summary of the hypotheses testing results.

Figure 2.

Standardized theoretical path coefficient. (Note: χ2 = 294.405, df = 126, χ2/df = 2.337, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.943, CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.959, and RMSEA = 0.064; NFI: normed fit index, IFI: incremental fit index, CFI: comparative fit index, TLI: Tucker–Lewis index, and RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation; * p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Standardized parameter estimates for structural model.

5. Discussions and Implications

This study examined image congruence in the context of robotic coffee shops. More specifically, image congruence was analyzed in three sub-categories including actual self-image, ideal self-image, and social self-image. Next, this study explored the impact of image congruence on the outcome variable brand attitude. Then, the influence of brand attitude on brand attachment and brand loyalty was examined. Finally, the relationship between brand attachment and brand loyalty was evaluated. In order to test the six hypotheses proposed in this study, data were collected and analyzed from 325 samples in South Korea.

First, all three of the sub-dimensions of image congruence, including actual, ideal, and social self-image were found to be significant factors of brand attitude. In particular, social self-image had the highest impact on brand attitude, followed by ideal and actual self-image, respectively. This means consumers of the robotic coffee shop consider how others view them while using the robot coffee shop the most. Consequently, if the customer feels others will think positively of them while using the robotic coffee shop, they are more likely to develop a positive brand attitude. Self-consistency motives describe an individuals’ social and actual self-image, while self-esteem motivates the ideal self-image [14]. According to the results of this study, customers of robotic coffee shops are motivated by both self-consistency and self-esteem.

Second, the results of this study confirmed that brand attitude has a positive relationship with brand attachment and brand loyalty. Robotic coffee shop consumers with a positive brand attitude are more likely to form brand attachment and brand loyalty to the robotic coffee shop. This aligns with previous studies that have found brand attitude impacts brand attachment and brand loyalty [42,59]. Seo, G. D. and Lee, J. E. [60] also confirmed the relationship among brand attitude, brand attachment, and brand loyalty in the context of coffee shops. However, the results of our study are the results of data strictly collected from a robotic coffee shop and are therefore meaningful in the aspect of service robot literature.

Third, the analysis results confirmed that brand attachment has a positive influence on brand loyalty. Patrons of the robotic coffee shop who develop a positive attachment to the brand are more likely to speak positively about this coffee brand to others, are more likely to use the coffee brand more often, and have the desire to use the coffee brand in the future. These results are consistent with previous studies that have found brand attachment positively affects brand loyalty in coffee shops [61]. On the contrary, Chan and Tung [62] found that customers had a lower emotional attachment to service received by service robots as opposed to human employees in a hotel setting. The results of our study are significant in that the customers had an attachment to the brand from the service received from a robot barista in the robotic coffee shop context. As a result of the analysis, the following theoretical and managerial implications are provided.

5.1. Major Theoretical Contributions

As previously mentioned, image congruence, including actual self-image, ideal self-image, and social self-image, positively impacts brand attitude in robot coffee shops (H1, H2 and H3). When the consumer has a positive image of how they actually view themselves while using the robot coffee shop, then their attitude towards the brand is positively influenced. Similarly, if the consumer visits the robot coffee shop and perceives an ideal image of themselves, they will develop a positive brand attitude. Lastly, if the consumer perceives that others view him or her positively when using the robot coffee shop, then they will have a positive attitude towards the brand. This study adds to the current literature on the topic of the self-congruity theory and helps to apply this theory to the context of robotic coffee shops. The results of this study also support and expand the existing literature regarding the relationship between image congruence and brand attitude in the coffee shop industry. Kang et al. [15] found that image congruence significantly impacts attitude in the context of Korean name-brand coffee shops. In Kang’s study, it was confirmed that consumers from collective cultures including Korea, tend to place emphasis on the social or ideal-social image of name-brand coffee shops. Our study expanded these results by exploring the context of robotic coffee shops and surveying a wider age range of respondents. On the other hand, Bajac, Palacios, and Minton [20] found that high collectivist cultures place less emphasis on congruence when evaluating products. The results of our study contradict this idea and conclude that congruence is an important factor for consumers from collectivist cultures.

Previous studies have also investigated the impact of image on outcome variables in new technology services. For example, Choe, Kim, and Hwang [63] discovered that image has a positive effect on the outcome variables in the drone food delivery service sector. Kim et al. [47] found that the overall image of robotic restaurants significantly affects outcome variables. Apart from other studies, this study discovered the relationship between image congruence and brand attitude in the robotic coffee shop industry for the first time, resulting in important theoretical applications. Neinstedt, Huber, and Seelmann’s [19] study investigated how actual and ideal congruence impacts brand relations and consumer loyalty in the media context. Our study goes one step further by including social self-image congruence as a variable.

Brand attitude was found to have a significantly positive relationship with brand attachment and brand loyalty (H4 and H5). Lastly, brand attachment was found to have a significantly positive influence on brand loyalty (H6). If the consumer has a positive attitude towards the robot coffee shop brand, they will most likely develop an emotional bond with the brand and feel passionate about receiving services from the robot barista. If the consumer develops a positive brand attitude, they will most likely become brand loyal and will want to visit the robot coffee shop often. These results were found similarly in previous studies across a variety of industries including the golf tournament and private country club industry [29]. Comparably, Back [12] concluded that when customers had a positive self-image in congruence with the image of a hotel, they were more likely to form a positive attitude toward the brand, ultimately leading to brand loyalty. If robotic coffee shops focus on the image of the coffee shop, they can expect an increase in brand attitude, brand attachment, and brand loyalty. Brand loyal consumers are more likely to say positive things about the coffee shop to others. Overall, the results of this study confirm the relationship among the variables of brand attitude, brand attachment, and brand loyalty. However, this study investigated the relationship between image congruence and brand attitude, brand attachment, and brand loyalty in the robotic coffee shops setting for the first time. Therefore, significant theatrical contributions as well as managerial implications were derived from the results of this study.

5.2. Managerial Implications

First, the results indicate that the customer’s self-image congruency has an effect on brand attitude. Considering the fact that consumers view the image of typical visitors to the robotic coffee shop as an important factor in whether they develop positive or negative feelings towards the brand, managers should develop a marketing information system allowing them to evaluate and analyze consumer perception of the coffee shop visitors [12]. Coffee shop managers should strive to evaluate the self-concept of the target customers and customize the image of the brand accordingly, in order to improve image congruence [19]. Advertising should be created based on the results of the marketing information system data.

Second, managers should continually update the robot barista’s technology, to ensure it stays user-friendly. If a customer were to have difficulty using services provided by a robot barista, this experience may negatively impact their self-image. Younger customers may be able to use robotic coffee shops more easily than older consumers. Therefore, managers should develop educational materials including step-by-step video demonstrations in order to empower older consumers to use robotic coffee shops with confidence.

Third, considering today’s consumers desire contact-free services, it would be beneficial to emphasize how robot baristas provide contactless services. Contact-free and advanced technological services offer benefits to our society, particularly in the pandemic situation where consumers seek minimal contact with unknown persons as well as hygienic services. This concept should be promoted by advertising smartphone applications that allow for wait times to be reduced by robot baristas Advertising these ideas may help to project a positive image of the brand overall.

Fourth, brand attitude positively influenced brand attachment and brand loyalty. This indicates that brand attitude is a significant variable to determining the success of the robotic coffee shop. Managers should focus particular attention to the overall brand attitude of the consumers. Creating coupon cards for return visitors can cultivate an attachment to the brand and help customers want to continue to visit often in the future. It is necessary to collect feedback from consumers via customer satisfaction surveys on a routine basis in order to assure the concerns and needs of the customers are addressed properly.

Lastly, managers of robotic coffee shops should make it a priority to keep up with any technological advances for the robot baristas. Installing technology where the robot baristas are able to display or even say a customer’s name may offer just the right amount of personal touch to help customers feel a deeper connection to the brand. Practitioners may also consider investing in technologies that allow the robot barista to perform slightly more advanced tasks, such as being able to create latte art, which can also help to boost the image of the coffee shop. Robot baristas will continue to become more infused into our society and it will be essential for managers to adopt proper managerial strategies to ensure the utmost services are provided to consumers.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Prior studies have observed the cross-cultural effect on consumer behavior [45] and the symbolic meanings associated with a brand may differ by culture [64]. Hence, more research is suggested to establish the significance of image congruence on brand preferences across different regions. Furthermore, the effect of image congruence tends to vary according to various internal and external factors [64,65]. For example, the degree of personal importance of a specific product/service type and technology readiness may affect the influence of image congruence on brand attitude in innovative technology adoption behavior. Thus, future studies can be motivated by incorporating diverse moderators such as consumer product involvement and innovativeness as well as other situational variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.K.; methodology, H.M.K.; validation, H.M.K. and K.R.; formal analysis, H.M.K.; investigation, K.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.K. and K.R.; writing—review and editing, H.M.K. and K.R.; supervision, K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. The Robot Coffee Shops

Figure A1.

Retrieved from Dal.komm, at http://www.dalkomm.com/ (accessed on 14 March 2021).

Appendix B. The Measurement Items

- Actual self-image congruence

- The typical visitor of the robotic coffee shop is consistent with how I see myself.

- The image of the typical visitor of the robotic coffee shop is a mirror image of me.

- The typical visitor of the robotic coffee shop reflects the type of person who I am.

- Ideal self-image congruence

- The typical visitor of the robotic coffee shop is consistent with how I would like to see myself.

- The image of the typical visitor of the robotic coffee shop is a mirror image of the person I would like to be.

- The typical visitor of the robotic coffee shop reflects the person I want to be.

- Social self-image congruence

- The typical visitor of the robotic coffee shop is similar to how other people see me.

- The image of the typical visitor of the robotic coffee shop is a mirror image of the person that other people think about me.

- The typical visitor of the robotic coffee shop reflects the person that others think I am.

- Brand attitude

- Attitude toward using this coffee shop brand…

- Unfavorable—Favorable

- Negative—Positive

- Bad—Good

- Brand attachment

- I love using this coffee brand.

- I am passionate about this coffee brand.

- I would feel sorry if this coffee brand ceased its operations.

- Brand loyalty

- I say positive things about this coffee brand to others.

- I would like to use this coffee brand more often.

- I would like to use this coffee brand in the future.

References

- Cain, L.N.; Thomas, J.H.; Alonso, M. From sci-fi to sci-fact: The state of robotics and AI in the hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 624–650. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.; Choi, Y.G.; Kim, J.J. A comparative study on the motivated consumer innovativeness of drone food delivery services before and after the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Park, S.; Kim, I. Understanding motivated consumer innovativeness in the context of a robotic restaurant: The moderating role of product knowledge. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.; Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Innovative marketing strategies for the successful construction of drone food delivery services: Merging TAM with TPB. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. Starbucks Is about to Look a Lot Different and COVID-19 Is Only Part of the Reason Why. Fast Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/90514230/starbucks-is-about-to-look-a-lot-different-and-COVID-19-is-only-part-of-the-reason-why (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Shim, J.; Moon, J.; Song, M.; Lee, W.S. Antecedents of purchase intention at Starbucks in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.J. Human baristas and robot baristas: How does brand experience affect brand satisfaction, brand attitude, brand attachment, and brand loyalty? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.J. The antecedents and consequences of memorable brand experience: Human baristas versus robot baristas. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robotics Tomorrow. Five Best Robot Coffee Baristas. Available online: https://www.roboticstomorrow.com/story/2020/05/five-best-robot-coffee-baristas/15296/#:~:text=The%20robot%20barista%20is%20a,the%20coffee%20to%20a%20customer (accessed on 29 May 2020).

- The Spoon. With Ella, Crown Coffee Is Transparent about Its Robot Barista Ambitions. Available online: https://thespoon.tech/with-ella-crown-coffee-is-transparent-about-its-robot-barista-ambitions (accessed on 29 May 2020).

- London, N. This Robot Barista Is Part of a Pandemic-Induced Entrepreneurial Boom. Colorado Public Radio. 2020. Available online: https://www.cpr.org/2020/11/14/this-robot-barista-is-part-of-a-pandemic-induced-entrepreneurial-boom/ (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Back, K.J. The effects of image congruence on customers’ brand loyalty in the upper middle-class hotel industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 29, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Using self-congruity and ideal congruity to predict purchase motivation. J. Bus. Res. 1985, 13, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Grewal, D.; Mangleburg, T.F.; Park, J.O.; Chong, K.S.; Claiborne, C.B.; Johar, J.S.; Berkman, H. Assessing the predictive validity of two methods of measuring self-image congruence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Tang, L.; Lee, J.Y.; Bosselman, R.H. Understanding customer behavior in name-brand Korean coffee shops: The role of self-congruity and functional congruity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abosag, I.; Ramadan, Z.B.; Baker, T.; Zhongqi, J. Customers’ need for uniqueness theory versus brand congruence theory: The impact on satisfaction with social network sites. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Image congruence and relationship quality in predicting switching intention: Conspicuousness of product use as a moderator variable. J. Hosp. Res. 2013, 37, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienstedt, H.W.; Huber, F.; Seelmann, C. The influence of the congruence between brand and consumer personality on the loyalty to print and online issues of magazine brands. Int. J. Media Manag. 2012, 14, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajac, H.; Palacios, M.; Minton, E.A. Consumer-brand congruence and conspicuousness: An international comparison. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Corfman, K.P. Quality and value in the consumption experience: Phaedrus rides again. In Perceived Quality; Jacoby, J., Olson, J., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, K.W. The antecedents and consequences of golf tournament spectators’ memorable brand experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Kim, I.; Hwang, J. A change of perceived innovativeness for contactless food delivery services using drones after the outbreak of COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.J.; Kim, I. Investigation of perceived risks and their outcome variables in the context of robotic restaurants. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jeon, S.M.; Hyun, S. Chain restaurant patrons’ well-being perception and dining intentions: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 402–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Koo, B.; Hyun, S.S. Image congruity as a tool for traveler retention: A comparative analysis on South Korean full-service and low-cost airlines. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, H. Perceived innovativeness of drone food delivery services and its impacts on attitude and behavioral intentions: The moderating role of gender and age. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. The Making and Breaking of Affectional Bonds; Tavistock: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Back, K.J. Relationships among image congruence, consumption emotions and customer loyalty in the lodging industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, K.S.; Chua, B.L.; Lee, S. Contribution of airline F&B to passenger loyalty enhancement in the full-service airline industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 380–395. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, D.; Kim, I. Robotic Restaurant Marketing Strategies in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Focusing on Perceived Innovativeness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Back, K.J. Examining antecedents and consequences of brand personality in the upper-upscale business hotel segment. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Samli, A.C. A path analytic model of store loyalty involving self-concept, store image, socioeconomic status, and geographic loyalty. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1985, 13, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijnen, M.; De Ruyter, K.; Andreassen, T.W. Image congruence and the adoption of service innovations. J. Serv. Res. 2005, 7, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Claiborne, C.B.; Sirgy, M.J. Self-image congruence as a model of consumer attitude formation and behavior: A conceptual review and guide for future research. In Proceedings of the 1990 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 25–29 April 1990; Springer: New York, NY, USA,, 2015; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Teng, L.; Foti, L.; Yuan, Y. Using self-congruence theory to explain the interaction effects of brand type and celebrity type on consumer attitude formation. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 103, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, J.; Mizerski, D.; Soh, H. Self-congruity, brand attitude, and brand loyalty: A study on luxury brands. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Vijaygopal, R. Consumer attitudes towards electric vehicles: Effects of product user stereotypes and self-image congruence. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 499–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, J. Exploring the role of healthy green spaces, psychological resilience, attitude, brand attachment, and price reasonableness in increasing hotel guest retention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.J.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Hwang, J. Application of consumer innovativeness to the context of robotic restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozbay, Z.; Karami, A.; Arghashi, V. The Relationship between brand Love and brand attitude. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Management and Business, Tebriz, Iran, 9 May 2018; pp. 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, D.; Yoo, M.M.; Lee, Y. A holistic view of the service experience at coffee franchises: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahri-Ammari, N.; Van Niekerk, M.; Khelil, H.B.; Chtioui, J. The effects of brand attachment on behavioral loyalty in the luxury restaurant sector. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 559–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, M.; Holland, S.; Townsend, K.M. Consumer-based brand authenticity and brand trust in brand loyalty in the Korean coffee shop market. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 45, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.I.; Wang, W.H. Impact of CSR perception on brand image, brand attitude and buying willingness: A study of a global café. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J. The role of customer familiarity in evaluating green servicescape: An investigation in the coffee shop context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Mukherjee, A. I am, ergo I shop: Does store image congruity explain shopping behaviour of Chinese consumers? J. Mark. Manag. 2007, 23, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Martin, D. Self-image congruence in consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A.; Olson, J.C. Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator of advertising effects on brand attitude? J. Mark. 1981, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.; Ahuvia, A. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relationship benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Nguyen, H.N.; Song, H.J.; Chua, B.L.; Lee, S.; Kim, W. Role of social network services (SNS) sales promotions in generating brand loyalty for chain steakhouses. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 20, 617–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, G.D.; Lee, J.E. A study on the effect of consumer lifestyle on brand attitude, brand attachment influence upon brand loyalty. J. Digit. Converg. 2016, 14, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. Antecedents and consequences of brand prestige of package tour in the senior tourism industry. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.H.; Tung, V. Examining the effects of robotic service on brand experience: The moderating role of hotel segment. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.; Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Perceived risk from drone food delivery services before and after COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1276–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.J.; Airey, D.; Siriphon, A. Chinese outbound tourism: An alternative modernity perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Rudolph, N. Undesired self-image congruence in a low-involvement product context. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).