Integrated Strategies for Household Food Waste Reduction in Bangkok

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

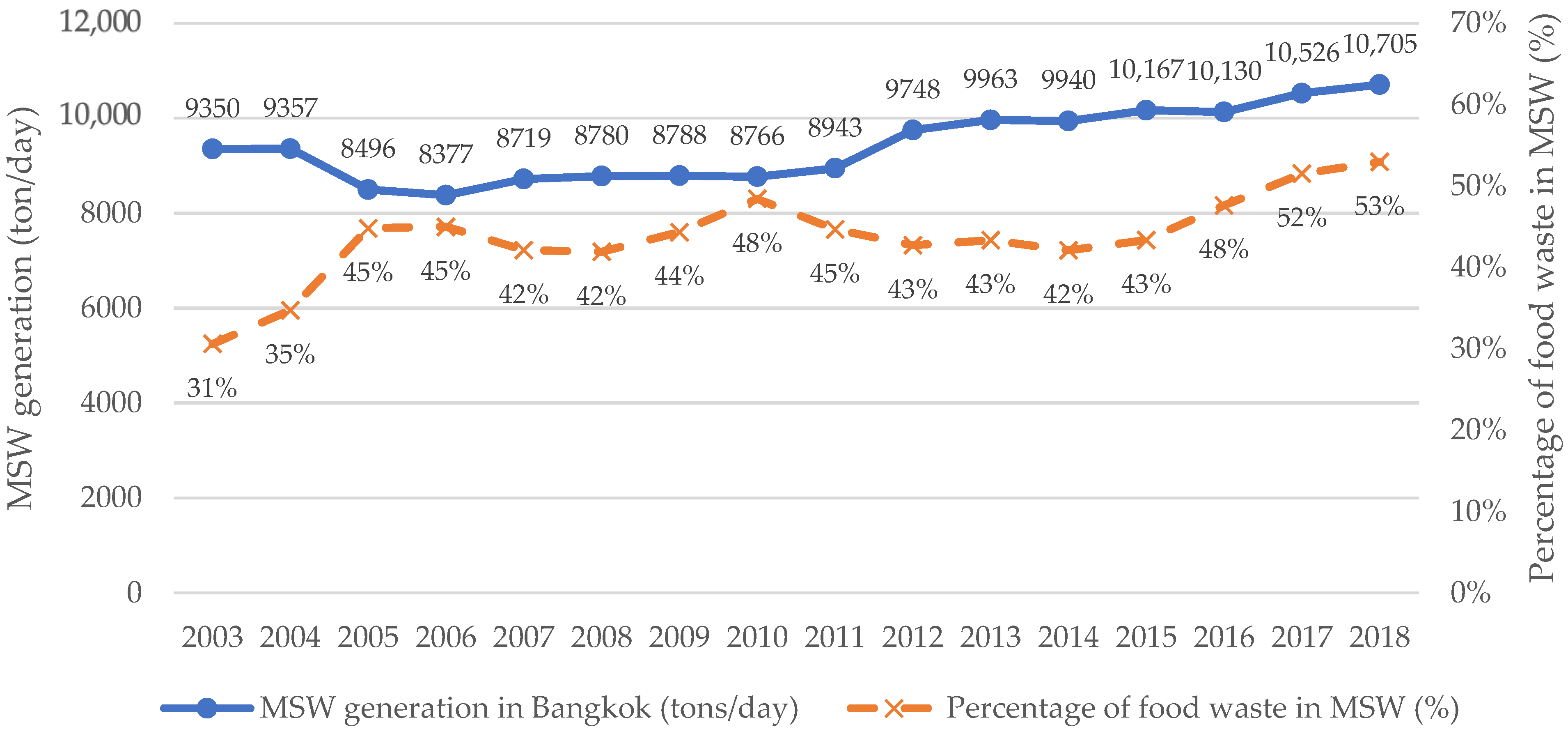

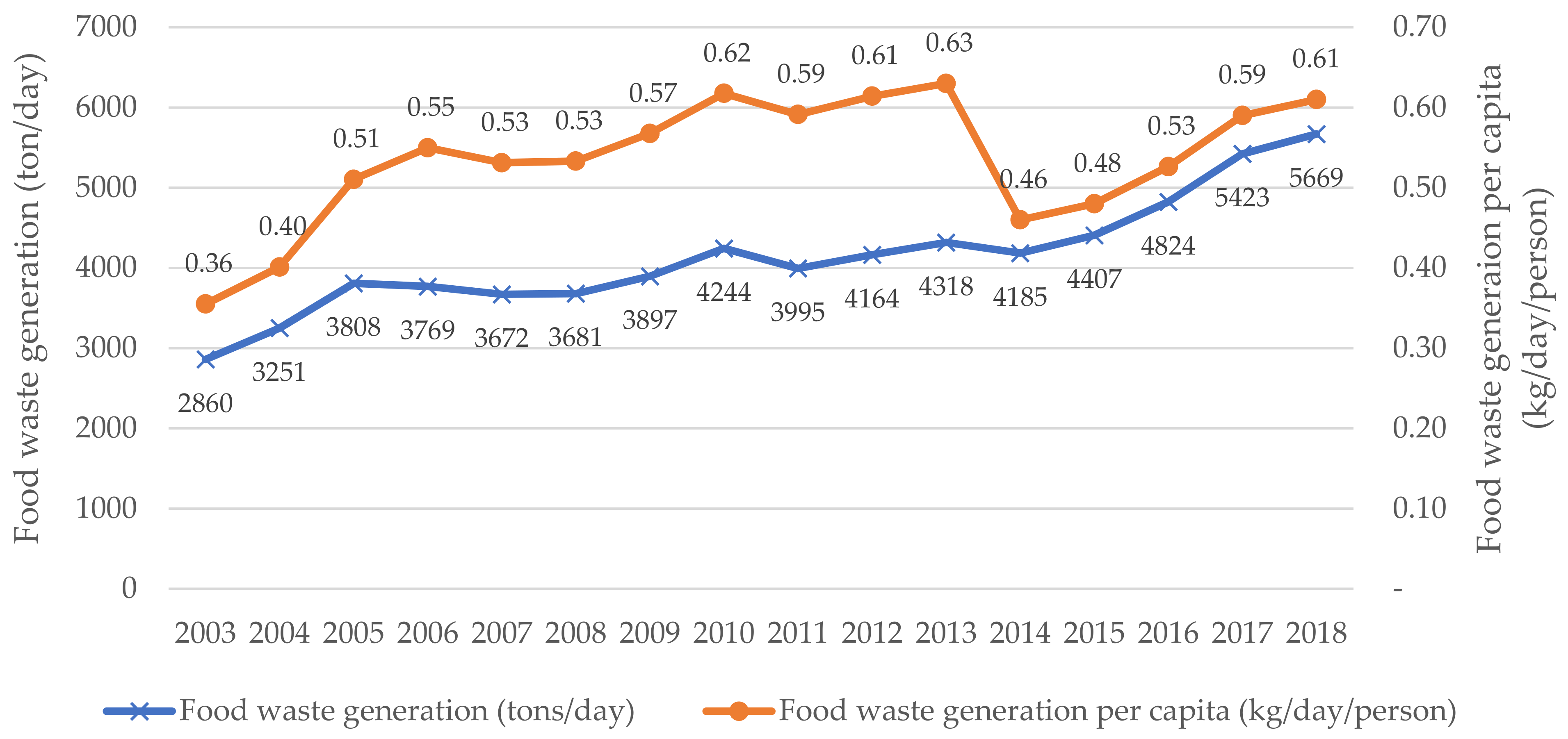

2.1. Food Waste (FW) Generation in Bangkok

2.2. Causes of Food Waste Generation

2.3. Impacts of Food Waste Generation

2.4. Food Waste Elimination Strategy

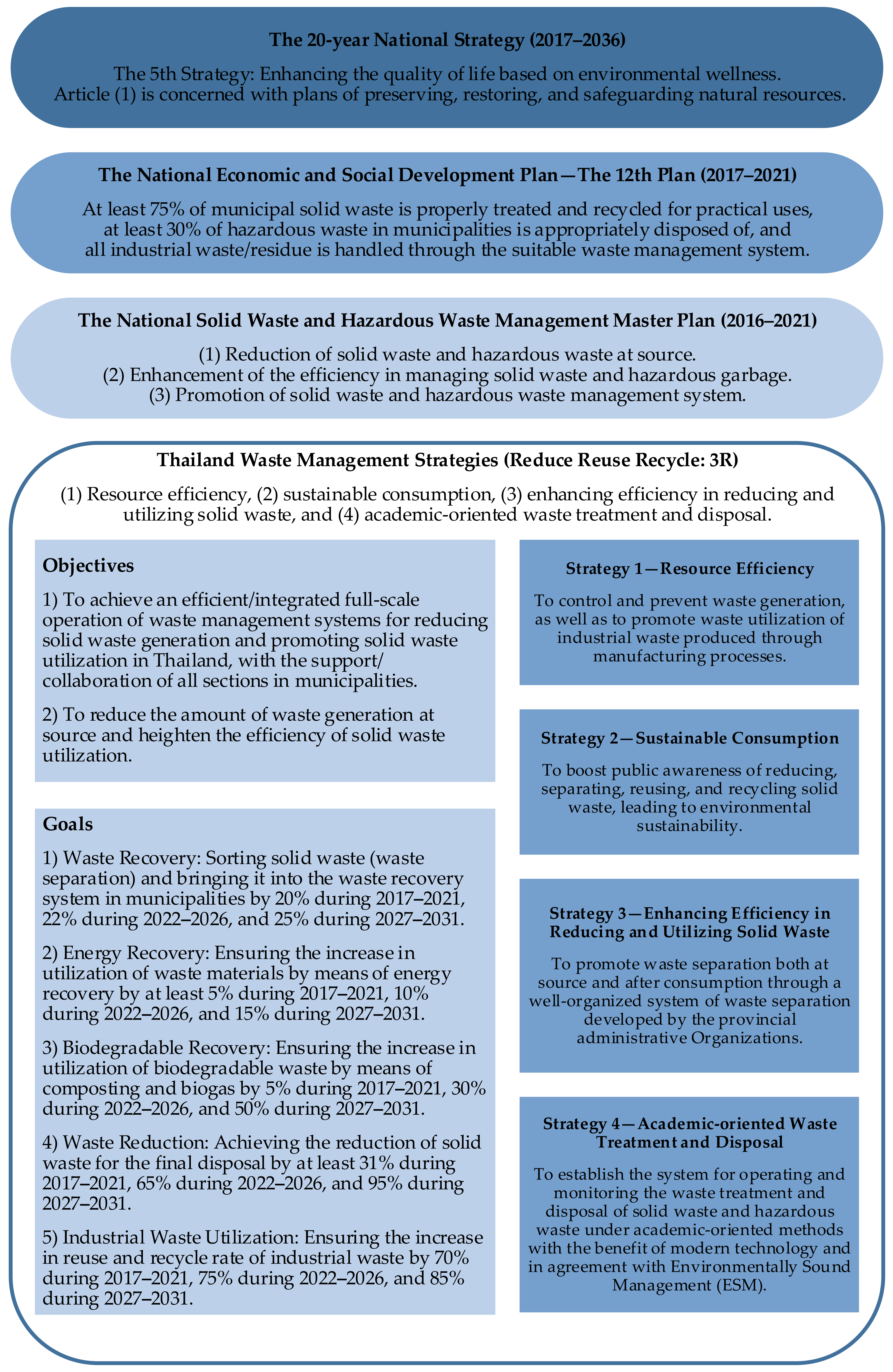

2.5. Related Policies, Strategies, and Plans on FW Reduction

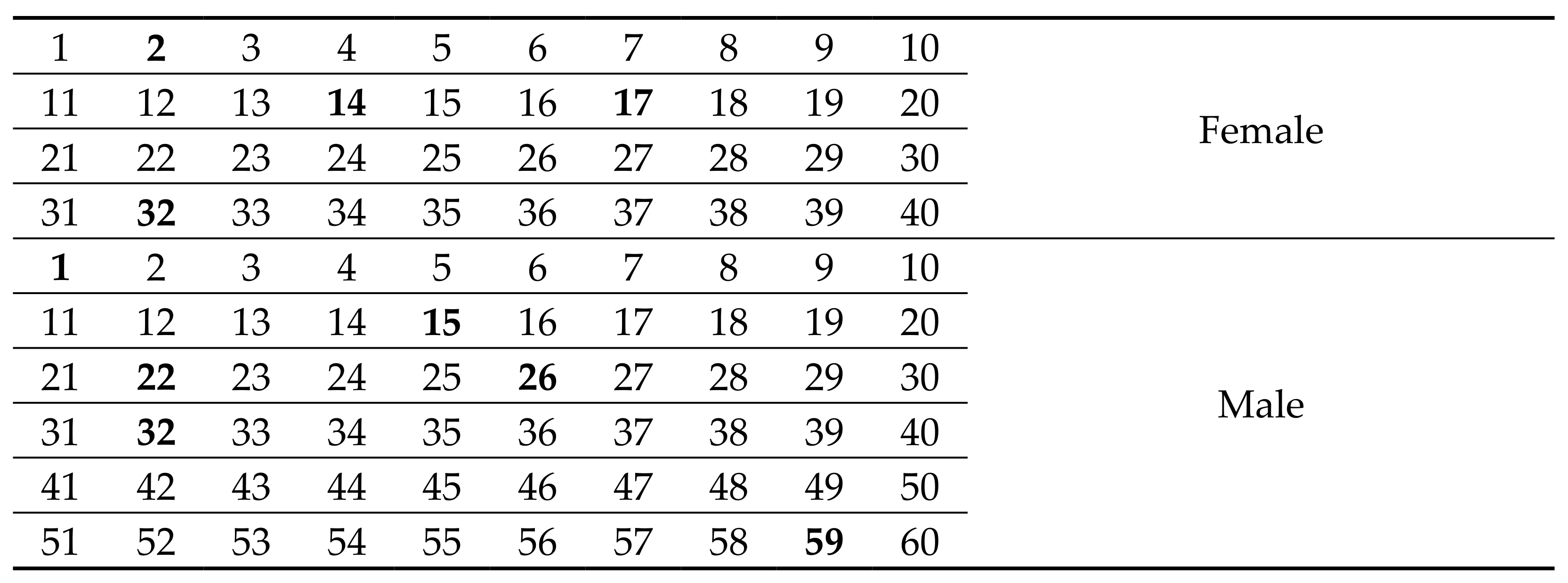

3. Data Collection: Survey of Daily Lifestyles and FW Generation

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Key Attributes from the Survey

4.2. Analyzing Factors Influencing Food Management

4.2.1. Food Waste Generation

4.2.2. Food Waste Separation

4.2.3. Reuse and Recycling of Food Waste

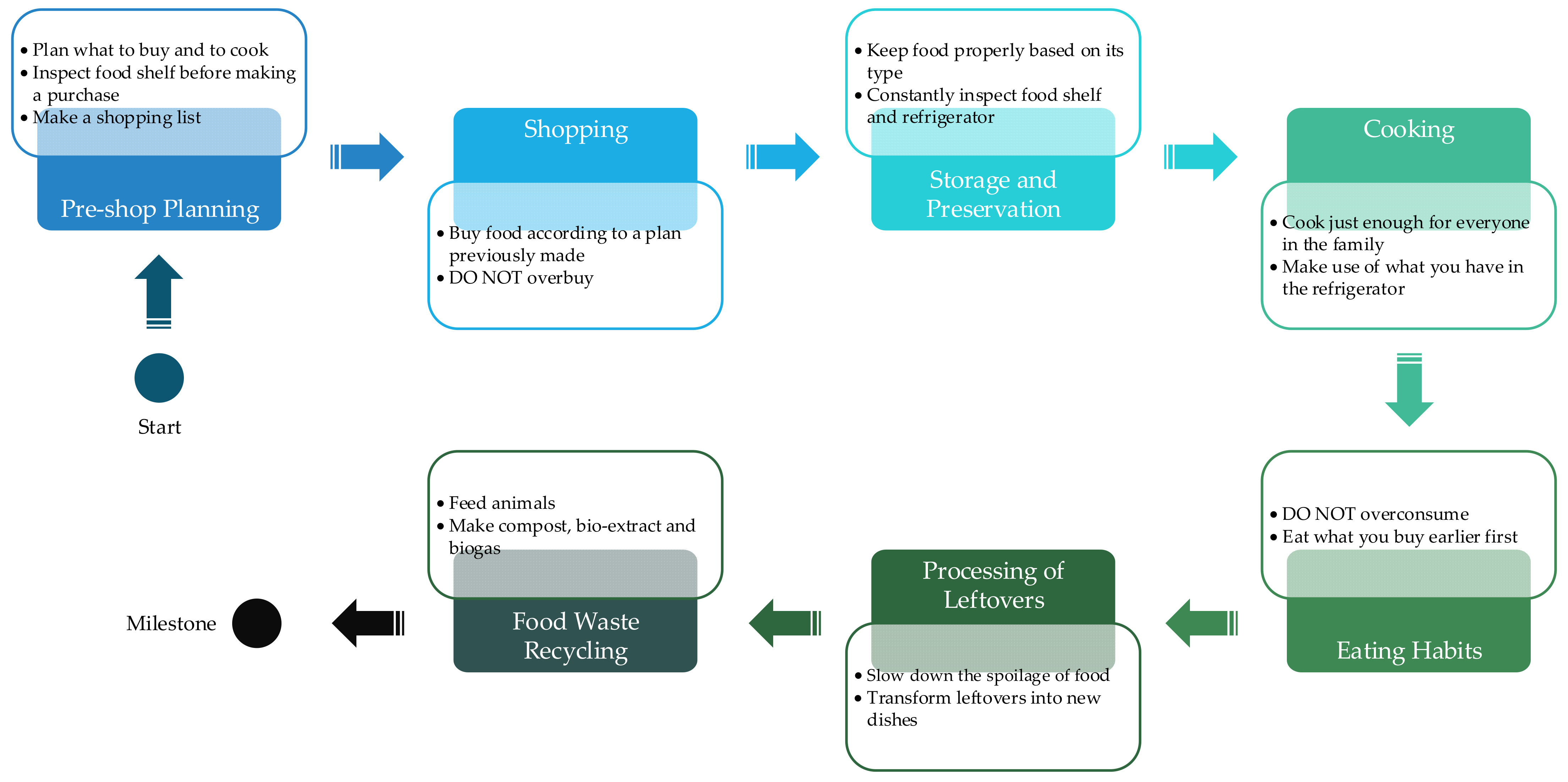

4.3. Development of Integrated Strategies for Household Food Management

- Pre-Shop Planning. The plan can help householders calculate appropriate portion sizes for food consumed by all members in the family without creating leftovers that must be thrown away. Methods include: (1) making a plan of what to buy and to cook; (2) inspecting food on the shelf and in the refrigerator before making a purchase so that householders can avoid buying what they already have; and (3) making a shopping list of foodstuffs to discourage overbuying.

- Shopping. Unnecessary food purchasing inevitably leads to food waste. Householders have to think carefully and take practical advice, such as (1) buying food according to a plan previously made and not overbuying items because of marketing ploys and (2) buying food that can be kept in proper containers and suits the demands of consumers.

- Storage and Preservation of Freshness. Food preservation to reduce food loss is linked to knowledge and skills of types of food. Householders should consider: (1) the appropriateness of storage in relation to types of food. Shelf life has to be taken into account when it comes to perishable ingredients, such as meat kept in the freezer, vegetables like coriander and celery kept in the vegetable compartment, and root vegetables like taro kept at room temperature. Characteristics of food are also important. For example, tofu should not be kept in the freezer as its nutrients will be lost. Weighty fruits should not be placed on top of fresh vegetables which can be easily discolored. Well-planned food storage can also extend the edible life of products. (2) Regularly inspecting the food shelf and refrigerator allows consumers to check the expiry dates of food to ensure that no edible food is thrown away. Different product labels need to be clarified to prevent confusion. ‘Best before’ labels show the date before which products still retain good quality in terms of color and taste when kept under proper conditions. These labels do not indicate spoilage of products. In contrast, ‘use by’ dates, similar to expiry dates, indicate when food becomes harmful to consume because of contamination.

- Cooking. Skills and knowledge in food preparation are essential in cooking. During the cooking process, householders should consider: (1) proper portioning that is suited to the demands of all household members to avoid waste and (2) cooking from what consumers already have before buying new ingredients. Old food that is still edible can also be added to new ingredients, such as cooking Thai basil minced pork and then adding baby corns from the previous meal.

- Eating Habits. Food waste often occurs during mealtimes. To reduce waste, it is crucial to consider the following points: (1) portions of food should not be too excessive. Consumers should not overserve the food and should use small-sized packages or containers for good portioning; and (2) priority must be taken into account when preparing old and new ingredients, as the former must be eaten first because of the impending expiry date.

- Processing of Leftovers. Food waste after consumption can be reduced by means of food processing to extend its life. Methods include: (1) food preservation, which is a way of slowing down the spoilage of vegetables, fruits, and meat. Pickled lettuce, dried fish, pickled chili, and fruit jam are well-known examples of processed products; and (2) food transformation. Cooked food that is left uneaten can be processed into some forms of new dishes. For example, boiled chicken left from Chinese ceremonies can be recooked to make salted chicken.

- Food Waste Recycling. Sometimes, leftovers cannot be safely recooked, and in this case, they can be used to (1) feed animals, such as cats, dogs, and catfish or (2) make compost, bio-extract, and biogas, if householders are well-supplied with resources for such products.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Katsarova, I. Tackling Food Waste: The EU’s Contribution to a Global Issue; European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS): Strasbourg, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Institution of Mechanical Engineers (ImechE). Global Food: Waste Not, Want Not; Institution of Mechanical Engineers: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UN News Center. Nearly 870 Million People Chronically Undernourished, Says New UN Hunger Report. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2012/10/423022#.VPFw4nysV4s (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Sharp, A.; Sang-Arun, J. A Guide for Sustainable Urban Organic Waste Management in Thailand: Combining Food, Energy, and Climate Co-Benefits; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Kanagawa, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Soma, T. (Re)framing the food waste narrative: Infrastructures of urban food consumption and waste in Indonesia. Indonesia 2018, 105, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangkuti, F.; Wright, T. Indonesia Retail Foods: Indonesia Retail Report Update 2013; Foreign Agricultural Service: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013; USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, Global Agricultural Information Network (GAIN). [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, D.; Robison, R. The New Rich in Asia: Mobile Phones, McDonald’s and Middle Class Revolution; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, T.; Hopkins, R. The supermarket revolution in developing countries: Policies to address emerging tensions among supermarkets, suppliers and traditional retailers. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2006, 18, 522–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C. Grocery shopping, food waste, and the retail landscape of cities: The case of Seoul. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Mao, C.; Bunditsakulchai, P.; Sasaki, S.; Hotta, Y. Food waste in Bangkok: Current situation, trends and key challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 157, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Food Losses and Food Waste in China: A First Estimate. In OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xue, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Cheng, S.; Liu, G. Horeca food waste and its ecological footprint in Lhasa, Tibet, China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Naseer, A.; Shahid, M.; Shah, G.M.; Ullah, M.I.; Waqar, A.; Abbas, T.; Imran, M.; Rehman, F. Assessment of nutritional loss with food waste and factors governing this waste at household level in Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.B.; Gorski, I.; Neff, R.A. Understanding and addressing waste of food in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1633–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Liu, B. Food Loss and Waste in the Food Supply Chain; International Nut and Dried Fruit Council: Reus, Spain, 2017; pp. 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- BMA. Bangkok State of the Environment 2015–2016; BMA: Bangkok, Thailand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BMA. Bangkok State of the Environment 2013–2014; BMA: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- BMA. Bangkok State of the Environment 2010–2011; BMA: Bangkok, Thailand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lammawichai, J. Solid Waste Management in Bangkok; BMA: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017; Available online: https://www.jesc.or.jp/Portals/0/center/training/10thasia3r/8.10thasia3r_bangkok.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Pollution Control Department, Ministry of Natural Resources Environment. Thailand State of Pollution Report 2018; Pollution Control Department, Ministry of Natural Resources Environment: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019.

- Pollution Control Department, Ministry of Natural Resources Environment. Thailand State of Pollution Report 2017; Pollution Control Department, Ministry of Natural Resources Environment: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018.

- Pollution Control Department, Ministry of Natural Resources Environment. Thailand State of Pollution Report 2015; Pollution Control Department, Ministry of Natural Resources Environment: Bangkok, Thailand, 2016.

- Department of Environment. Handbook of Community Based Solid Waste Management; Department of Environment: Bangkok, Thailand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Policy and Planning Division. Waste Collection Trucks for the Fiscal Year of 2014; The Bangkok Metropolitan Administration: Bangkok, Thailand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sukholthaman, P.; Sharp, A. A system dynamics model to evaluate effects of source separation of municipal solid waste management: A case of Bangkok, Thailand. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungrungrueng, S. Bangkok towards sustainable waste management. In Proceedings of the management of the Sai Mai waste transfer and disposal station, Bangkok, Thailand; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- The Nation. Monthly Garbage Fees to Quadruple as New Disposal Cost Adde. The Nation. 9 May 2019. Available online: https://www.nationthailand.com/national/30369133 (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food Waste within Food Supply Chains: Quantification and Potential for Change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Food Loss Prevention in Perishable Crops. Agriculture Services bulletin No. 43; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, L.; Dora, M.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kumar, V. Improving the sustainability of food supply chains through circular economy practices—A qualitative mapping approach. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 752–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, R.J.; Buzby, J.C.; Bennett, B. Postharvest Losses and Waste in Developed and Less Developed Countries: Opportunities to Improve Resource Use. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 149, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Priefer, C.; Jörissen, J.; Bräutigam, K. Technology Options for Feeding 10 Billion People: Options for Cutting Food Waste; Science and Technology Options Assessment (STOA): Brussels, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P.; Willis, P. Waste Arisings in the Supply of Food and Drink to UK Households; Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP): Banbury, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Food: Too Good to Waste Pilot; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-Region 10: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti Soup: The Complex World of Food Waste Behaviour. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Preparation Study on Food Waste across EU27; BIO Intelligence Service: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.; Hipps, N.; Hails, S. Helping Consumers Reduce Fruit and Vegetable Waste: Final Report; Ipsos MORI and Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP): Banbury, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bekteş, A. Research and Product Design to Minimize Food Waste in Western Domestic Kitchens. Master's thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Corrado, M. Understanding Consumer Food Management Behaviour; Ipsos MORI and Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP): Banbury, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Canali, M.; Amani, P.; Aramyan, L.; Gheoldus, M.; Moates, G.; Östergren, K.; Silvennoinen, K.; Waldron, K.; Vittuari, M. Food waste drivers in Europe, from identification to possible interventions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ponis, S.T.; Papanikolaou, P.-A.; Katimertzoglou, P.; Ntalla, A.C.; Xenos, K.I. Household food waste in Greece: A questionnaire survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska, B.; Tomaszewska, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Analysis of the behaviors of polish consumers in relation to food waste. Sustainability 2020, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP). Understanding Food Waste; Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP): Banbury, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz, R. Causes of Food Waste Generation in Households—An Empirical Analysis; University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences: Vienna, Austria; Cranfield University: Vienna, Austria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chenene, L.M.L. The Relationship between Household-Generated Food Waste in Rural and Urban Lesotho: An Investigation; University of the Free State: Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F. Wasting Food—An Insistent Behaviour. Available online: http://analyseplatformen.dk/Data/madspildsmonitor/HTML_madspildsplatform/assets/schneider_2008_wasting-food--an-insistent-behaviour..pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Parizeau, K.; von Massow, M.; Martin, R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, L.; Abiad, M.G.; Chalak, A.; Diab, M.; Hassan, H. Attitudes and behaviors shaping household food waste generation: Lessons from Lebanon. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grethe, H.; Dembélé, A.; Duman, N. How to Feed the World’s Growing Billions. Understanding FAO World Food Projections and Their Implications; Heinrich Böll Stiftung und WWF Deutschland: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.; Downing, P. Food Behaviour Consumer Research: Quantitative Phase; Ipsos MORI and Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP): Banbury, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa, H.; Williams, I.; Shaw, P.; Watanabe, K. Food waste prevention: Lessons from the Love Food, Hate Waste campaign in the UK. In Proceedings of the 16th International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium, S. Margherita di Pula, Italy, 2–6 October 2017; pp. 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, C.; Denniss, R.; Baker, D. Wasteful Consumption in Australia; The Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Government Office of Science. The Future of Food and Farming: Challenges and Choices for Global Sustainability; The Government Office of Science: London, UK, 2011.

- UN-Water. Water in a Changing World; World Water Assessment Programme (UNESCO WWAP): Istanbul, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani, M.; Davary, K.; Teimori, L.A.M.; Shafiei, M. Investigating and Selecting of Assessment Indexes for Sustainable Water Management at Watershed Scale. J. Irrig. Sci. Eng. 2021, 44, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, K.; Guo, J.; Dore, M.; Chow, C. The Progressive Increase of Food Waste in America and Its Environmental Impact. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexander, P.; Brown, C.; Arneth, A.; Finnigan, J.; Moran, D.; Rounsevell, M.D. Losses, inefficiencies and waste in the global food system. Agric. Syst. 2017, 153, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsuwan, P. Municipal Solid Waste: The Significant Problem of Thialand; National Assembly Library of Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ventour, L. The Food We Waste; Exodus Market Research and Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP): Banbury, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiyasut, C. Bioextract. Pathumthani: National Science and Technology Development Agency; NSTDA Bookstore: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Nakakubo, T. Comparative assessment of waste disposal systems and technologies with regard to greenhouse gas emissions: A case study of municipal solid waste treatment options in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 120827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Bilitewski, B.; Zhu, N.; Chai, X.; Li, B.; Zhao, Y. Environmental impacts of a large-scale incinerator with mixed MSW of high water content from a LCA perspective. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 30, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniscalco, M.P.; Volpe, M.; Messineo, A. Hydrothermal carbonization as a valuable tool for energy and environmental applications: A review. Energies 2020, 13, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Gong, Z.; Si, B.; Zhai, Y. Persulfate assisted hydrothermal processing of spirulina for enhanced deoxidation carbonization. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 322, 124543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Si, B.; Gong, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Cao, M.; Peng, C. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of food waste-woody sawdust blend: Interaction effects on the hydrochar properties and nutrients characteristics. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 316, 123900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Zhai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Zeng, G. A review of the hydrothermal carbonization of biomass waste for hydrochar formation: Process conditions, fundamentals, and physicochemical properties. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCRD. Country 3R Progress Report Kingdom of Thailand, 2018. In Proceedings of the Eight Regional 3R Forum in Asia and the Pacific, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India, 9–12 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chanhthamixay, B.; Vassanadumrongdee, S.; Kittipongvises, S. Assessing the sustainability level of municipal solid waste management in Bangkok, Thailand by wasteaware benchmarking indicators. Appl. Environ. Res. 2017, 39, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.J.; Ampt, E.S.; Meyburg, A.H. Survey Methods for Transport Planning; Eucalyptus Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane, T. Statistics, an Introductory Analysis; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Losiri, C.; Nagai, M.; Ninsawat, S.; Shrestha, R.P. Modeling urban expansion in Bangkok metropolitan region using demographic–economic data through cellular automata-Markov chain and multi-layer perceptron-Markov chain models. Sustainability 2016, 8, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strategy and Evaluation Department, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration. Statistical Profile of Bangkok Metropolitan Administration 2020; Strategy and Evaluation Department, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maddala, G.S.; Lahiri, K. Introduction to Econometrics; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan, A. Econometric Analysis of Discrete Choice: With Applications on the Demand for Housing in the US and West-Germany; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 296. [Google Scholar]

- Asteriou, D.; Hall, S.G. Applied Econometrics; Macmillan International Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meadowcroft, D.P. Understanding the Effect of Product Displays on Consumer Choice and Food Waste: A Field Experiment; University of Delaware: Newark, DE, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, H.; Saphores, J.-D. Information and the Decision to Recycle: Results From a Survey of US Households. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2009, 52, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.A.; Alavi, N.; Goudarzi, G.; Teymouri, P.; Ahmadi, K.; Rafiee, M. Household recycling knowledge, attitudes and practices towards solid waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 102, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geffen, L.; van Herpen, E.; van Trijp, H. Household Food waste—How to avoid it? An integrative review. Food Waste Manag. 2020, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; De Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-related food waste: Causes and potential for action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roodhuyzen, D.M.; Luning, P.A.; Fogliano, V.; Steenbekkers, L. Putting together the puzzle of consumer food waste: Towards an integral perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Causes | Explanation and Support Evidence |

|---|---|

Planning | Over-purchasing and lack of planning are among the factors that lead to an increase in household FW. Most consumers who do not plan their food purchases are likely to buy more food than they need [33]. Lee and Willis’s study [34] in the UK discovered that 5.3 million tons, or 64% of household food waste, is avoidable. In addition, a survey in Germany also showed that 59% of household food waste comes from ill-organized planning and suboptimal food storage. By age group, teenagers are less likely than adults to plan their food purchasing in advance [35]. Good pre-shopping planning or using shopping lists are some efficient ways to prevent excessive spending [36] particularly in reducing over-purchase [35]. |

Food date labeling | Confusion over shelf-life and expiry dates on food labels, such as ‘best before’ date or ‘use by’ date, means that plenty of edible food is unnecessarily thrown away [37]. ‘Best before’ labels show the date before which products still retain good qualities in terms of color and taste when kept under proper conditions. The labels, however, do not indicate spoilage of products. When a product goes past its regulated specified date, consumers can choose whether they want to eat it or not by considering its color and taste. In contrast, a ‘use by’ date indicates when a food product becomes harmful to consume because of contamination. The use by date is quite similar to an expiry date, also known as EXP or Exp. Date. The quality of the food, in terms of texture, color, smell, taste, nutrition, and microorganisms, will deteriorate after the regulated date. As such, it fails to meet the required standards and is best discarded. These labeling distinctions can leave consumers baffled. For instance, more than 50% of consumers in the UK tend to be confused by the difference between the ‘best before’ and ‘use by’ dates, with 20% of all food waste stemming from such label-related confusion [34]. |

Portion sizes | Package size can also be linked with the amount of food waste. Larger packs of food are generally popular among consumers, because they are cheaper than foodstuffs sold in small- and medium-sized packaging. Food bought in bulk can lead to more waste because consumers are not able to finish the product before it starts to decay. On the other hand, while small-sized packages help to reduce food waste, they can also generate more waste in other forms, such as plastic and glass. Therefore, if consumers have sufficient knowledge about food storage, preservation, and freezing, then they can buy food in bulk or in large-sized packages and make a significant contribution to reducing food waste and packaging, as well as saving money. |

Unnecessary purchase | FW tends to increase if consumers buy food that is not needed at the time of purchase [36]. Overstocking often leads to more waste generation because food is not eaten by the expiry date. Furthermore, advertisements that tempt consumers into trying new foodstuffs are also another factor in FW generation. This means some food is likely to be thrown away simply because consumers try it once and find they do not like it. |

Storage | When storing food, it is vital to maintain proper levels of humidity, light, and temperature as these have an impact on food deterioration and spoilage [35]. Poor food storage results in more waste, whereas proper food storage helps extend product shelf-life [37]. Knowledge about food storage also depends on the age of consumers. Older consumers are inclined to organize storage space better than younger consumers [38,39]. Consumer behavior focuses on convenience products, which also means that people do not need to know about food preservation and cooking. Another way to prevent food waste is to re-arrange food storage space frequently. That way, it is possible to check how much food is on the shelf and what the expiry dates are. A survey has shown that when people do not carry out sufficient cleaning and inspection of food storage space, many food products tend to be thrown away [35]. |

Cooking skills and knowledge | According to Corrado’s study [40], food waste is attributed to a lack of cooking and food preparation skills. Such skills are linked to age. Older people tend to have more skills than young people in this regard. Younger people are more likely to burn or spoil food when they cook and prepare food [40,41,42,43]. In the UK, 50% of people under the age of 24 lack the ability to cook food using ingredients they already have in their refrigerators, so they are forced to buy new foodstuffs. They also do not often make good use of leftovers [43,44]. Proper portioning and good preparation techniques play a useful part in reducing food waste [35]. |

Eating habits | According to Glanz’s study [43,45,46], food waste is also related to eating habits. Consumers who neglect to prepare in advance when purchasing food often end up throwing away rotten food in landfills. Householders who cook and eat food at home tend to produce less food waste than those who dine out [47,4849]. Up to 60% of food waste in the UK is generated during the cooking and preparation process and from excessive portions of food. |

Socio-economic trends | Rising wages and changes in consumer behavior are linked to the increased amount of food waste [50]. Affluent households are inclined to produce more food waste [29]. This relationship corresponds to the European Union’s study showing that the amount of food loss tends to increase dramatically in line with household income. The increased amount of food waste has also been linked to consumption patterns, such as the rising trend in imported food product consumption. This is because imported products have quite a short shelf life. Another issue is that women who work outside the home affect the household food management because daily food purchase becomes more difficult without their help. These households inevitably buy and store in large quantities each week, leaving large amounts of food unused which has to be thrown away [33]. |

Demographic change | The shift from extended family to nuclear family in society is also connected to an increased amount of food waste. This is because the average rate of waste disposal per person in the nuclear family is higher than that in the extended family, because food sharing is less common in the nuclear family. Furthermore, teenagers are likely to produce more food waste than older people as they are less experienced in planning and preparing meals, and often do not have the skills to properly manage food waste [50,51,52,53,54]. |

| Impacts | Explanation and Support Evidence |

|---|---|

Food resources | The food industry is the largest generator of greenhouse gases, accounting for 14% of all emissions. Greenhouse gases generated by agricultural sectors are either directly discharged, such as methane and nitrous oxide from composting, livestock, and rice farming, or indirectly discharged from deforestation in order to cultivate lands for food production [33]. |

Food industry | The food industry also consumes the most resources. Food production in agricultural sectors uses up to 70% of all fresh water [56,57 ]. Water usage is likely to increase by 10–13 trillion square meters a year by the middle of the 21st century [3]. Moreover, monoculture farming uses vast amounts of chemicals in the form of fertilizers and insecticides which are causing contamination of the soil and water. This has a negative impact on biodiversity and ecosystem services [33]. It is clear that if food is excessively and mindlessly consumed and mostly ends up in garbage bins, natural resources will be lost without any real advantages for humankind. |

Environmental impacts | Food waste will eventually become biodegradable material, which has substantial impacts, namely (1) degradation and deposition causing emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas that accelerates global warming [58,59], (2) food waste elimination requiring large spaces for burial, a more popular method of disposal than incineration which requires high energy consumption, and (3) decomposition of food waste, causing leachate that seeps into groundwater and other natural water sources affecting human water consumption [60]. |

Economic impacts | The 1.3 billion tons of food waste each year has an economic value of USD 750 billion [4]. In the UK, food disposal costs USD 10.2 billion. Each year, households incur costs of up to USD 420 to dispose of household food waste. Meat and fish make up the majority of waste, costing USD 602 million each year. The cost for wasted bread, apples, and potatoes is USD 360 million, USD 317 million, and USD 302 million, respectively. Fresh food dumped before its expiry date costs up to USD 950 million each year [61]. A survey has also shown that people are generally not particularly aware of the value of the food they throw away. Up to 24% of people never think of the cost of food waste. Another issue is that there are fees incurred from waste collection services provided by government and private sectors. |

| Category | Attributes | Number of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 101 |

| Female | 121 | |

| Age | ≤20 | 4 |

| 21–30 | 102 | |

| 31–40 | 42 | |

| 41–50 | 27 | |

| 51–60 | 29 | |

| >60 | 18 | |

| Occupation | Company employee | 81 |

| Self-employed | 44 | |

| Daily-based labor | 12 | |

| Part-timer | 1 | |

| Full-time housewife | 7 | |

| Farmer/Agriculturist | 1 | |

| Government officer | 37 | |

| Student (university, junior college, etc.) | 25 | |

| Unemployed (including pensioners) | 12 | |

| Others | 2 | |

| Level of Education | No schooling | - |

| Primary school | 33 | |

| Lower secondary school | 16 | |

| Upper secondary school (High school) | 17 | |

| Vocational or technical university | 16 | |

| University | 100 | |

| Master’s Degree or higher | 40 | |

| Household income | ≤5000 THB/month | 2 |

| 5001–10,000 THB/month | 6 | |

| 10,001–15,000 THB/month | 25 | |

| 15,001–30,000 THB/month | 46 | |

| 30,001–50,000 THB/month | 59 | |

| 50,001–100,000 THB/month | 53 | |

| >100,000 THB/month | 31 |

| Factors Affecting the Frequency of Throwing Foods/Ingredients away before Trying Them | Coefficient | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (1 = male, 0 = female) | 0.0924 | 0.359 | |

| Age | −0.0051 | 0.285 | |

| Level of education | −0.0024 | 0.946 | |

| Characteristics of family | |||

| No. of children under 18 years old | 0.0676 | 0.202 | |

| No. of adults 19–55 years old | −0.0084 | 0.801 | |

| No. of elderly above 55 years old | 0.0274 | 0.674 | |

| Household income | −0.0060 | 0.900 | |

| Type of residence (1 = dormitory, 0 = somewhere else) | 0.0492 | 0.726 | |

| Period of residence | 0.0033 | 0.475 | |

| Checking foods/ingredients in the refrigerator before going shopping, where 1 = always, 2 = usually, 3 = sometimes, 4 = rarely, 5 = never | 0.1035 | 0.012 * | |

| Frequency of making “leftovers” when eating out, where 1 = often, 2 = sometimes, 3 = rarely, 4 = never | 0.3255 | 0.000 * | |

| Constant | 1.3453 | 0.002 * | |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.1645 | RMSE = 0.7318 | Prob > F = 0.0000 | |

| Factors Affecting the Frequency of Food Waste Separation before Disposal | Marginal Effect | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (1 = male, 0 = female) | 0.0296 | 0.274 |

| Age | −0.0022 | 0.147 |

| Level of education | 0.0024 | 0.847 |

| Characteristics of family | ||

| No. of children under 18 years old | −0.0051 | 0.829 |

| No. of adults 19–55 years old | 0.0172 | 0.075 * |

| No. of elderly above 55 years old | 0.0182 | 0.329 |

| Household income | −0.0024 | 0.838 |

| Type of residence (1 = dormitory, 0 = somewhere else) | 0.0848 | 0.169 |

| Period of residence | −0.0013 | 0.297 |

| Frequency of throwing foods/ingredients away before eating them, where 1 = often, 2 = sometimes, 3 = rarely, 4 = never | −0.0326 | 0.058 * |

| Frequency of making leftovers when eating out, where 1 = often, 2 = sometimes, 3 = rarely, 4 = never | −0.0211 | 0.221 |

| General waste separation (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −0.2964 | 0.000 * |

| Reuse/recycle (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −0.0582 | 0.089 * |

| Factors Affecting Reuse and Recycling Activities | Marginal Effect | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (1 = male, 0 = female) | −0.0933 | 0.086 |

| Age | −0.0119 | 0.004 * |

| Level of education (schooling years) | 0.0313 | 0.015 * |

| Characteristics of family | ||

| No. of children under 18 years old | 0.0059 | 0.236 |

| No. of adults 19–55 years old | 0.0238 | 0.030 * |

| No. of elderly above 55 years old | −0.0299 | 0.161 |

| Household income | −0.2220 | 0.119 |

| Type of residence (1 = dormitory, 0 = somewhere else) | −0.0609 | 0.149 |

| Frequency of throwing foods/ingredients away before eating them, where 1 = often, 2 = sometimes, 3 = rarely, 4 = never | 0.2182 | 0.089 * |

| Frequency of making leftovers when eating out, where 1 = often, 2 = sometimes, 3 = rarely, 4 = never | 0.1090 | 0.092 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bunditsakulchai, P.; Liu, C. Integrated Strategies for Household Food Waste Reduction in Bangkok. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147651

Bunditsakulchai P, Liu C. Integrated Strategies for Household Food Waste Reduction in Bangkok. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147651

Chicago/Turabian StyleBunditsakulchai, Pongsun, and Chen Liu. 2021. "Integrated Strategies for Household Food Waste Reduction in Bangkok" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147651

APA StyleBunditsakulchai, P., & Liu, C. (2021). Integrated Strategies for Household Food Waste Reduction in Bangkok. Sustainability, 13(14), 7651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147651