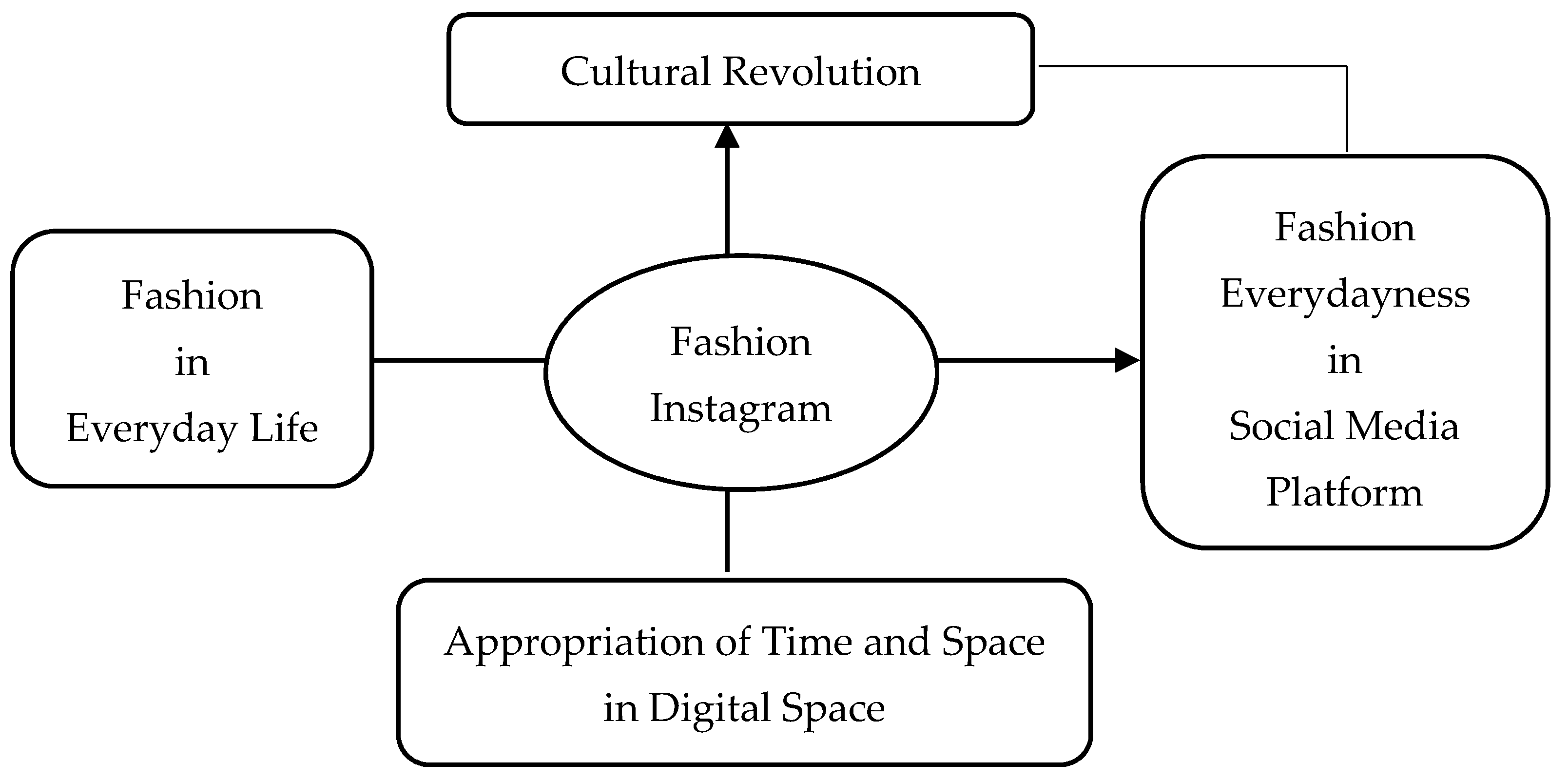

Fashion Everydayness as a Cultural Revolution in Social Media Platforms—Focus on Fashion Instagrammers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fashion in Everyday Life

“Fashion and everyday life are somewhat multivalent terms. Everyday life can refer to both experience and synchronicity. The everyday experience is in its typical form today, as it was yesterday and will be tomorrow; what constitutes everyday life changes according to the time and place. Fashion was integral to everyday life in the 20th century, and its impact grew as the century progressed. As a visual spectacle and material object, fashion offered the potential for the extraordinary to occur in the context of the everyday, thus enabling transformations in appearance and identities”.[15] (p. 1)

2.2. Digital Everydayness as Cultural Revolution

2.2.1. The Concept of Cultural Revolution

2.2.2. The appropriation of Time and Space in Digital Space

2.2.3. Digital Everydayness and Fashion

“The everyday is situated at the intersection of two modes of repetition: the cyclical, which dominates in nature, and the linear, which dominates in processes known as rational. The days follow one after another and resemble one another, and yet here lies the contradiction at the heart of everydayness: everything changes, but the change is programmed”.[16] (p. 10)

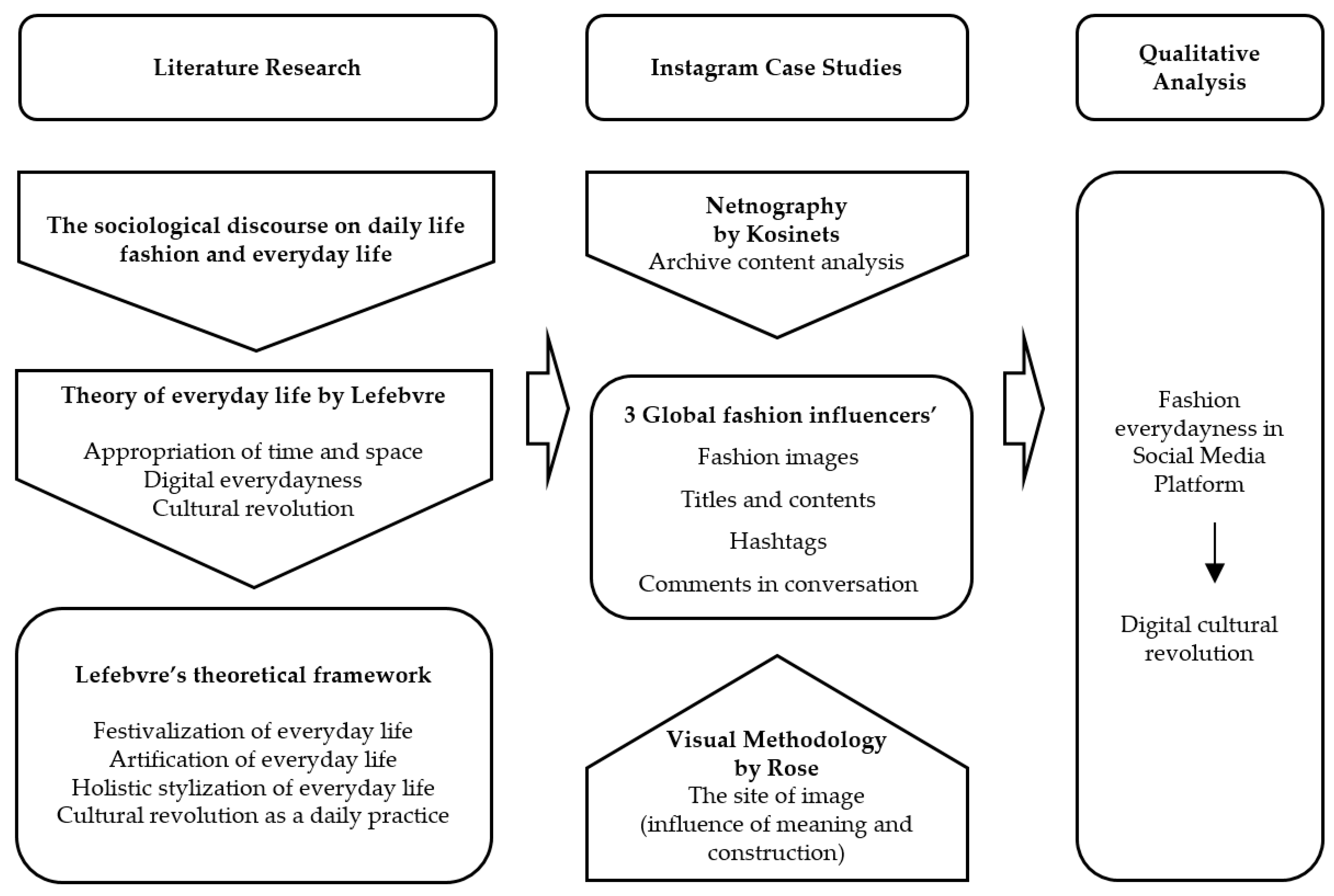

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion: Fashion Everydayness in Selected Instagrams

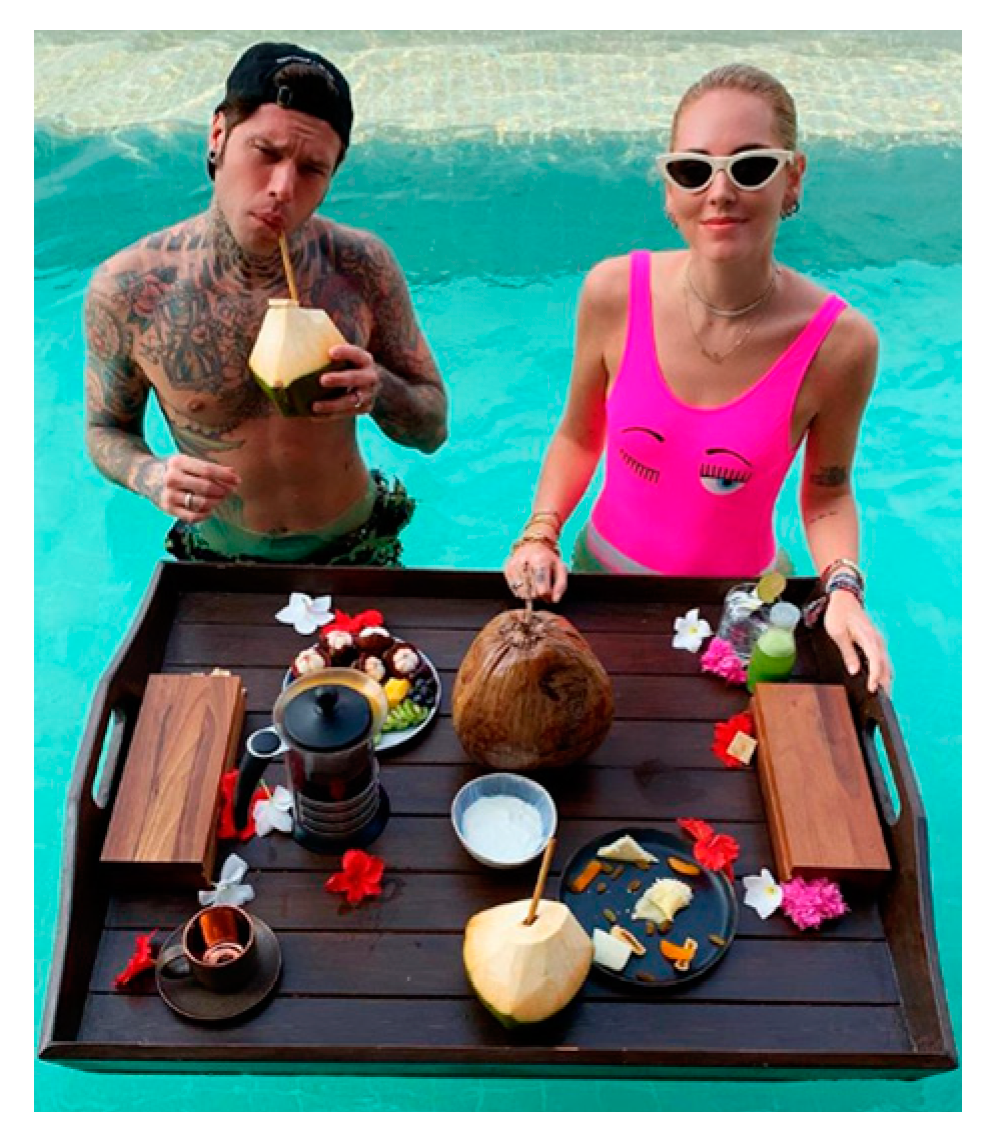

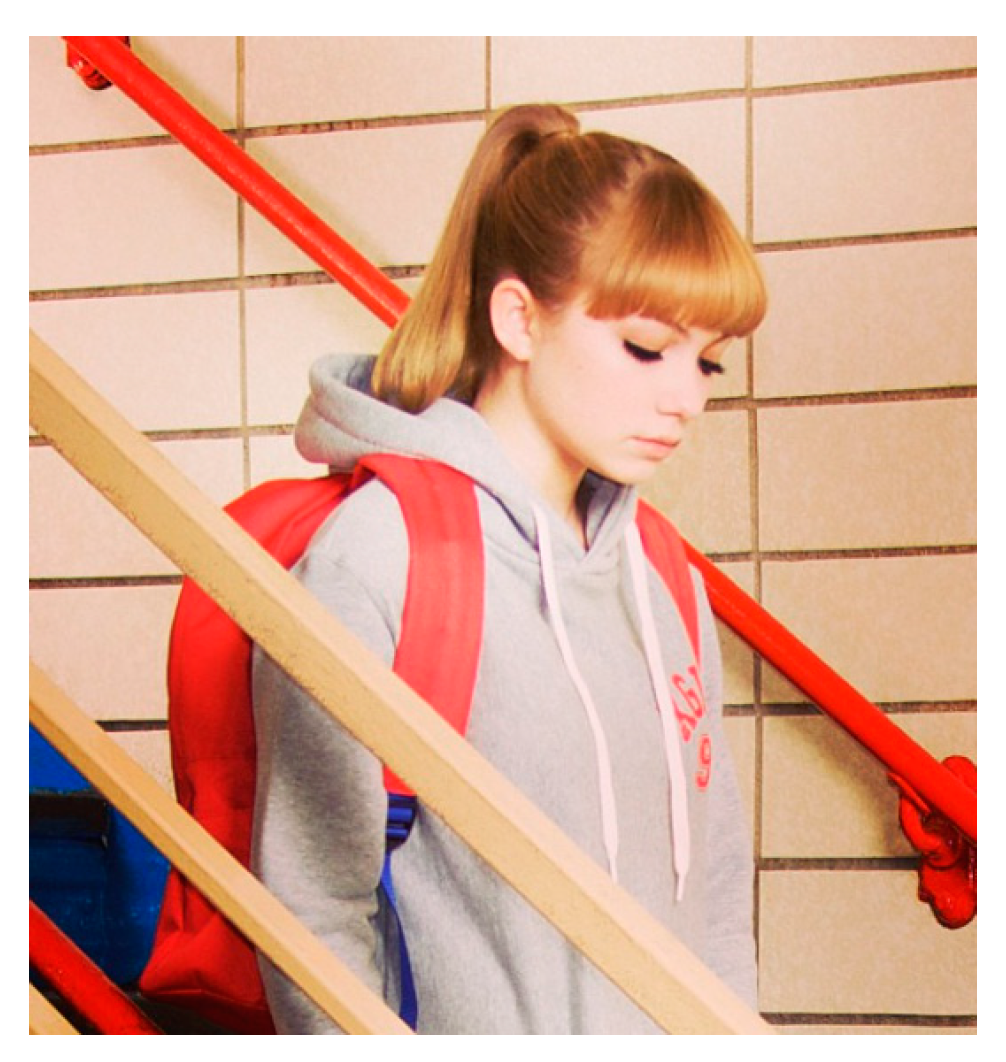

4.1. The Festivalization of Everyday Life

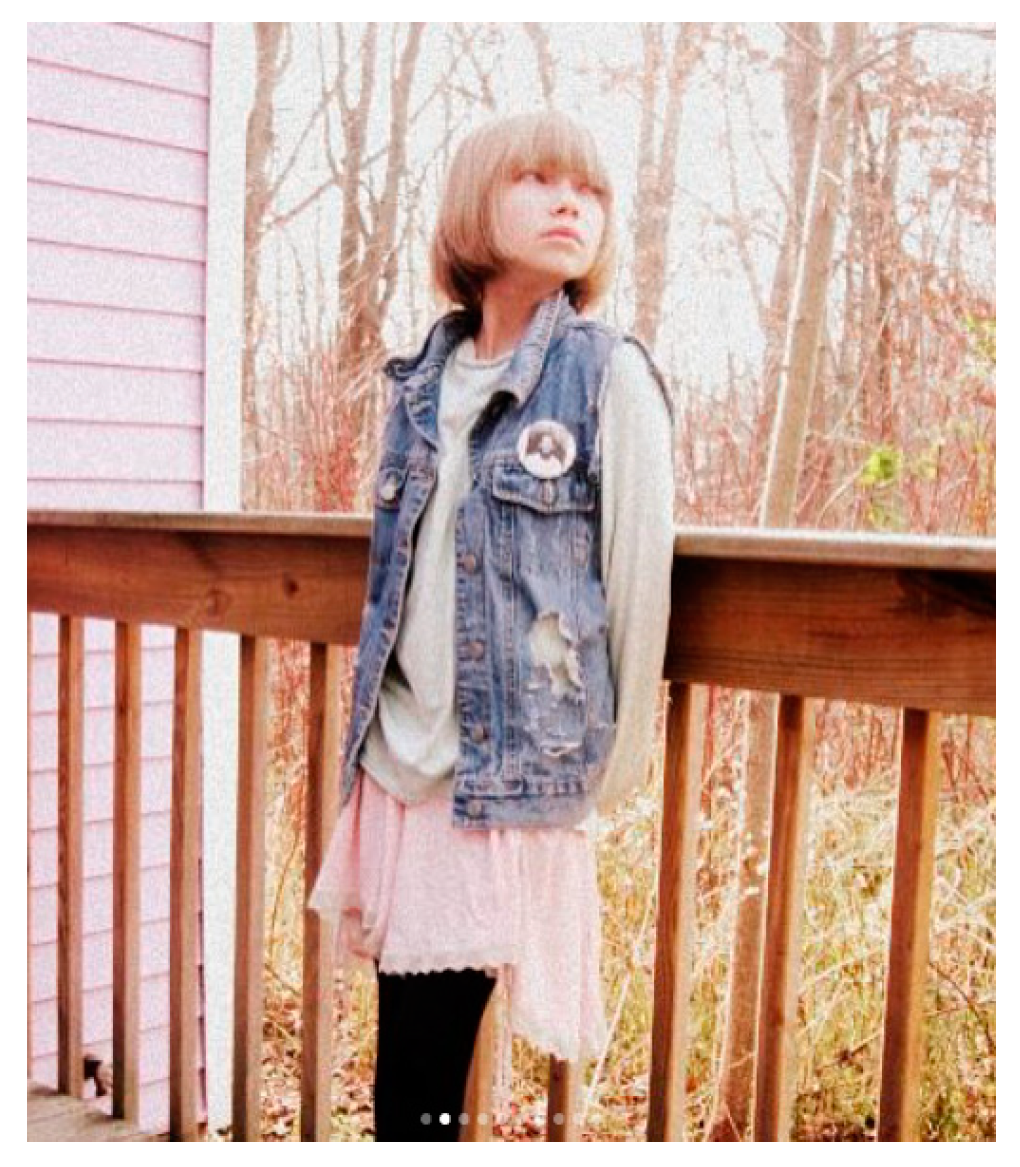

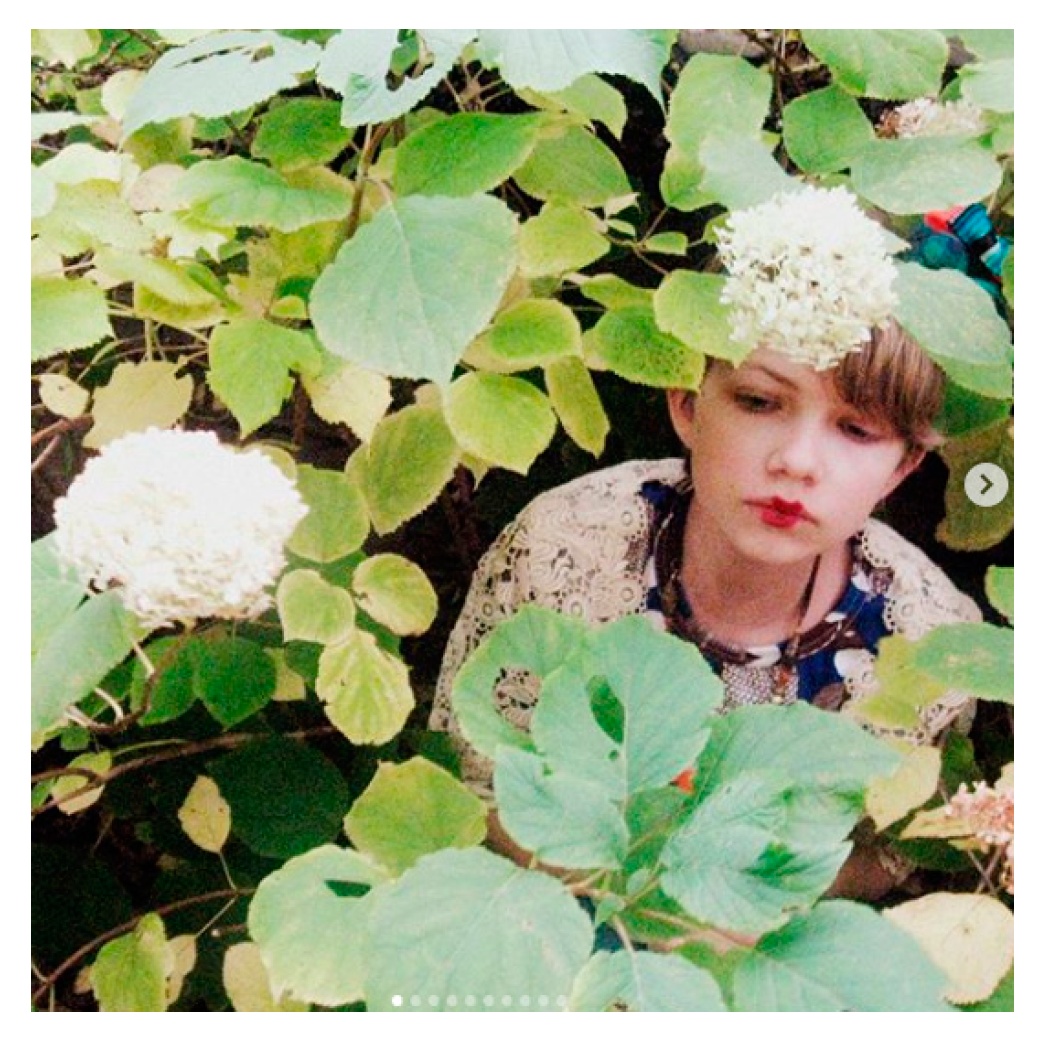

4.2. The Artification of Everyday Life

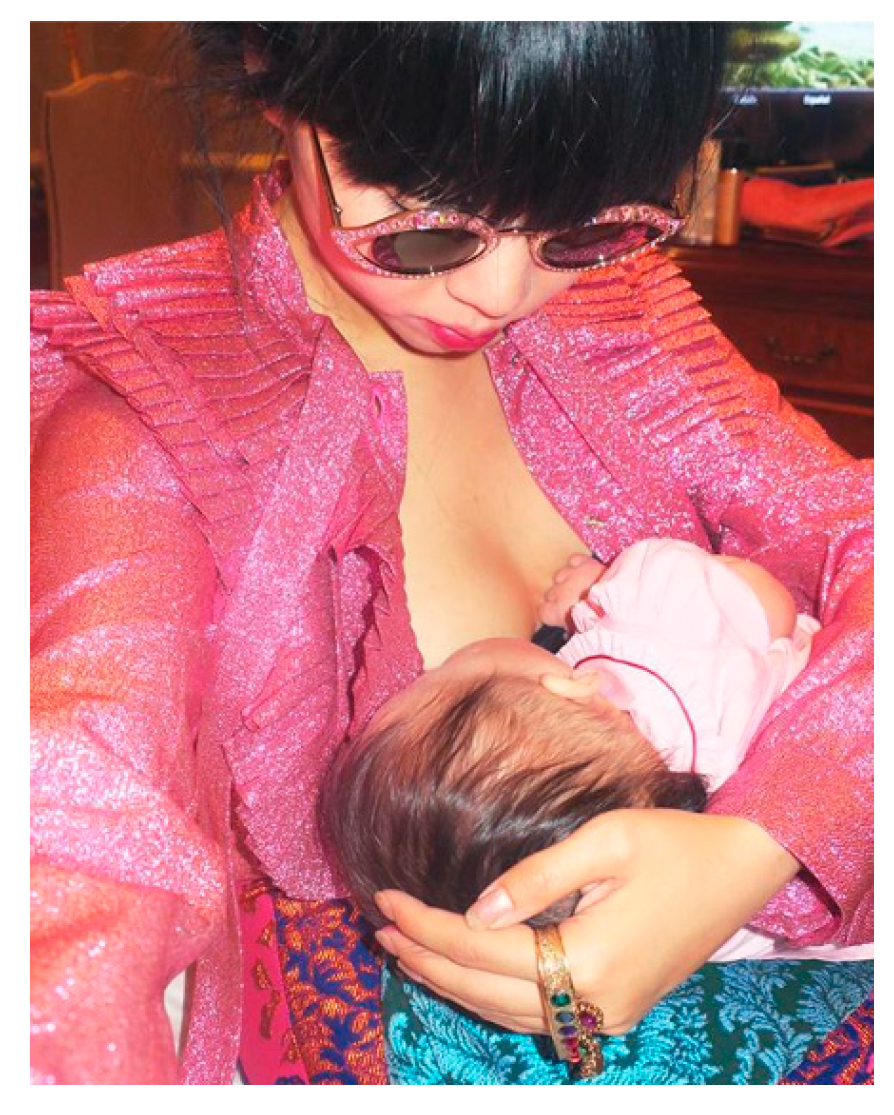

4.3. The Holistic Stylization of Everyday Life

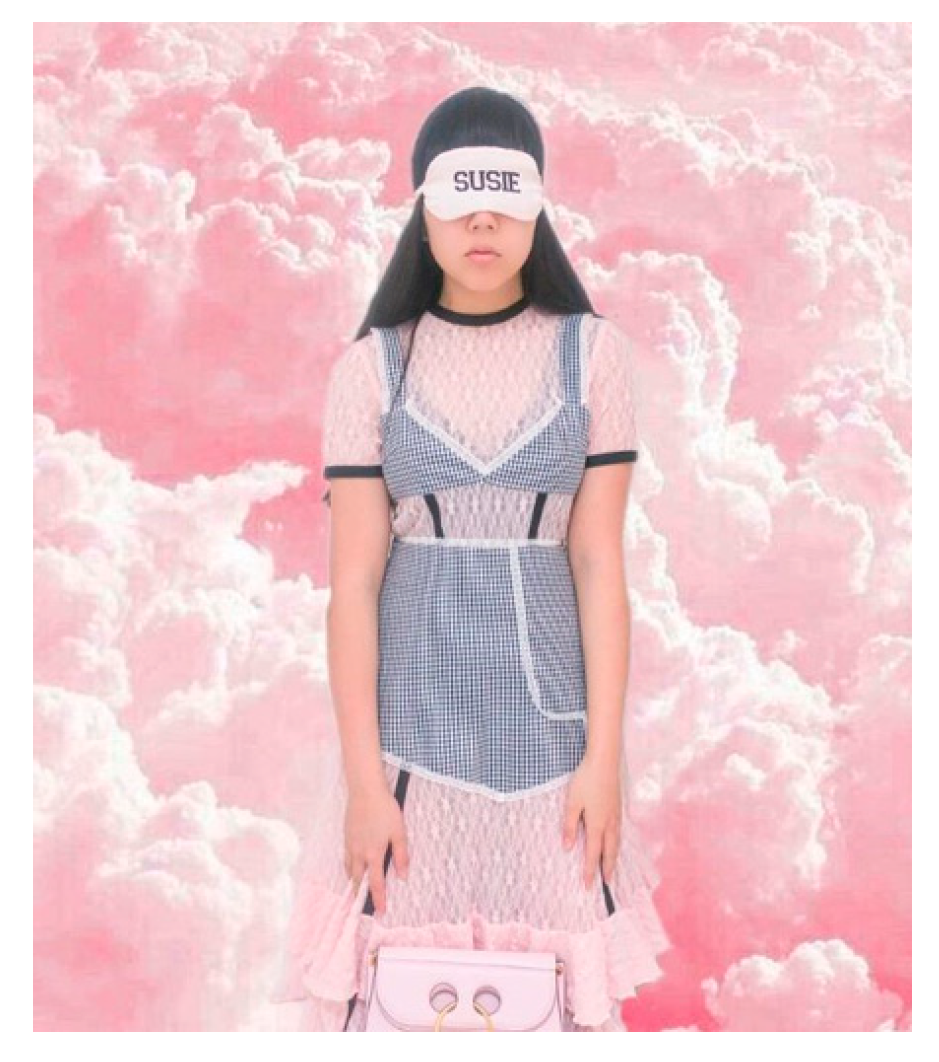

4.4. Cultural Revolution as Daily Practice

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.G.; Park, S.H. A Study on the everydayness of digital society. J. Korean Socio Assoc. 2010, 44, 611–622. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.E. The decentralized structure of time-space of the everyday life. Korean Socio 2010, 44, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.W. Henri Lefebvre; Communication Books: Seoul, South Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life; University of California Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Maffesoli, M.; Tacussel, P. Notes Sur La Postmodernité: Le Lieu Fait Lien; Éditions du Félin: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shinkle, E. Fashion’s digital body: Seeing and feeling in fashion interactives. In Fashion Media: Past and Present; Bartlett, D., Cole, S., Rocamora, A., Eds.; London Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2013; pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Rocamora, A. Personal fashion blogs: Screens and mirrors in digital self-portraits. Fashion Theory 2011, 4, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.E.; Kim, M.J. Imaginary ego-image and fashion styles represented in the social media; focusing on women’s personal fashion blogs. J. Korean Soc. Costume 2014, 64, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rocamora, A. Hypertextuality and the fashion media: The case of fashion blogs. J. Pract 2012, 6, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocamora, A. How new are new media? The case of fashion blogs. In Fashion Media: Past and Present; Bartlett, D., Cole, S., Rocamora, A., Eds.; London Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2013; pp. 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rocamora, A. Mediatization and digital media in the field of fashion. Fashion Theory 2017, 21, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R. Establishing reputation, maintaining independence: The modest fashion blogosphere. In Fashion Media: Past and Present; Bartlett, D., Cole, S., Rocamora, A., Eds.; London Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2013; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Luis, M.V.; Ana-Isabel, V.; Ubaldo, C. Fashion promotion on Instagram with eye tracking: Curvy girl influencers versus fashion brands in Spain and Portugal. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ahmed, S.C.; Deng, S.; Wang, H. Success of social media marketing efforts in retaining sustainable online consumers: An empirical analysis on the online fashion retail market. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, C.; Clark, H. Fashion and Everyday Life: London and New York; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H.; Levich, C. The everyday and everydayness. Yale Fr. Stud. 1987, 73, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannilli, G.L. How can everyday aesthetics meet fashion? Stud. Estetica 2017, 45, 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, J.; Wilson, E. Chic. Thrills: A Fashion Reader; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.Y. Imagination of social space and everydayness in the postmodern era. Episteme 2007, 1, 62–83. [Google Scholar]

- Highmore, B. (Ed.) The Everyday Reader; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. La Vie Quotidienne Dans le Monde Moderne; Guiparang Publishing: Seoul, South Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Elements de Rythmanalyse; Galmuri: Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. La Production L’espace; Eco Libre: Seoul, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Go, G.S. Cultural politics in space: For the cultural arrangement of spatial globality. Spa Environ. 2000, 14, 80–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Moon, S.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Bae, Y.; Choi, S.H. Social Media in Global Era and the Future of Digital Culture Strategy; Humanculture-arirang: Kyeonggi, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nasmedia. Netizen Profile Research Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/nasmedia/2018-nprnasmediaf (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Son, D.H. Instagram enthusiasm, Economychosun. 2018. Available online: http://economychosun.com/client/news/view.php?boardName=C00&t_num=13554&img_ho= (accessed on 28 November 2018).

- Kim, B.S.; Son, M.G.; Jeong, S.N. Spatial and Temporal Reconstruction of Everyday Life; The Academy of Korean Studies: Sungnam, Korea, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y. Strategy for Entering Ubiquitous Society. Institute of Information Technology Assessment; Korea Information & Communication Research Institute: Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.H. What Will Change the World; Kyobo: Seoul, South Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, Y. Fashion-Ology; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ormston, R.; Spencer, L.; Barnard, M.; Snape, D. The Foundations of Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K. A Handbook of Media and Communication Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kozinets, R.V. The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. J. Market. Res. 2002, 39, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V. Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. Sage publications, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.; Slater, D. Internet: An. Ethnographic Approach; Berg Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M.D.; Llodrà, I.; Jiménez, A.I. Social media as information sources and their influence on the destination image: Opportunities for sustainability perception. In Managing Sustainable Tourism Resources; Batabyal, D., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 265–283. ISBN 9781522557722. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Critique of Everyday Life; Verso: NY, New York, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.J. Dreaming of space of difference: Space production and practice. Space Soc. 2000, 14, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, M.; Burrows, R. (Eds.) Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk: Cultural of Technological Embodiment; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.T. Comparative study of theories of everyday life. Korean Socio 1994, 28, 85–118. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, S.E. Digital fashion image aura represented in the Burberry Instagram. J. Korean Soc. Costume 2017, 67, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suh, S. Fashion Everydayness as a Cultural Revolution in Social Media Platforms—Focus on Fashion Instagrammers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051979

Suh S. Fashion Everydayness as a Cultural Revolution in Social Media Platforms—Focus on Fashion Instagrammers. Sustainability. 2020; 12(5):1979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051979

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuh, Sungeun. 2020. "Fashion Everydayness as a Cultural Revolution in Social Media Platforms—Focus on Fashion Instagrammers" Sustainability 12, no. 5: 1979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051979

APA StyleSuh, S. (2020). Fashion Everydayness as a Cultural Revolution in Social Media Platforms—Focus on Fashion Instagrammers. Sustainability, 12(5), 1979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051979