Mapping the Food Festivals and Sustainable Capitals: Evidence from Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the spatial distribution of food festivals in Poland?

- What is the capitals potential of the location festivals in Poland?

- What are the conditions for the locating food festivals in Poland?

- What is the role of tourism capital in the capital conversion process?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Capital Theory

- attributes of the attractiveness of the destination: equipment, accommodation prices, and transport networks [42];

- historic and cultural sites, nightlife, outdoor activities, natural environment and openness, human hospitality [43];

- landscape [44];

- clean and quiet environment, quality of accommodation facilities, family facilities, safety, accessibility, reputation, entertainment, and recreational opportunities [45];

- festivals as an element embedded in local ecosystems of sport, culture, and business [18];

- events related to the region’s sporting heritage and other smaller sporting events, including mass sporting and recreational events [46].

2.2. Concept of Embeddedness

2.3. Concept of Sustainable Food System

3. Materials and Methods

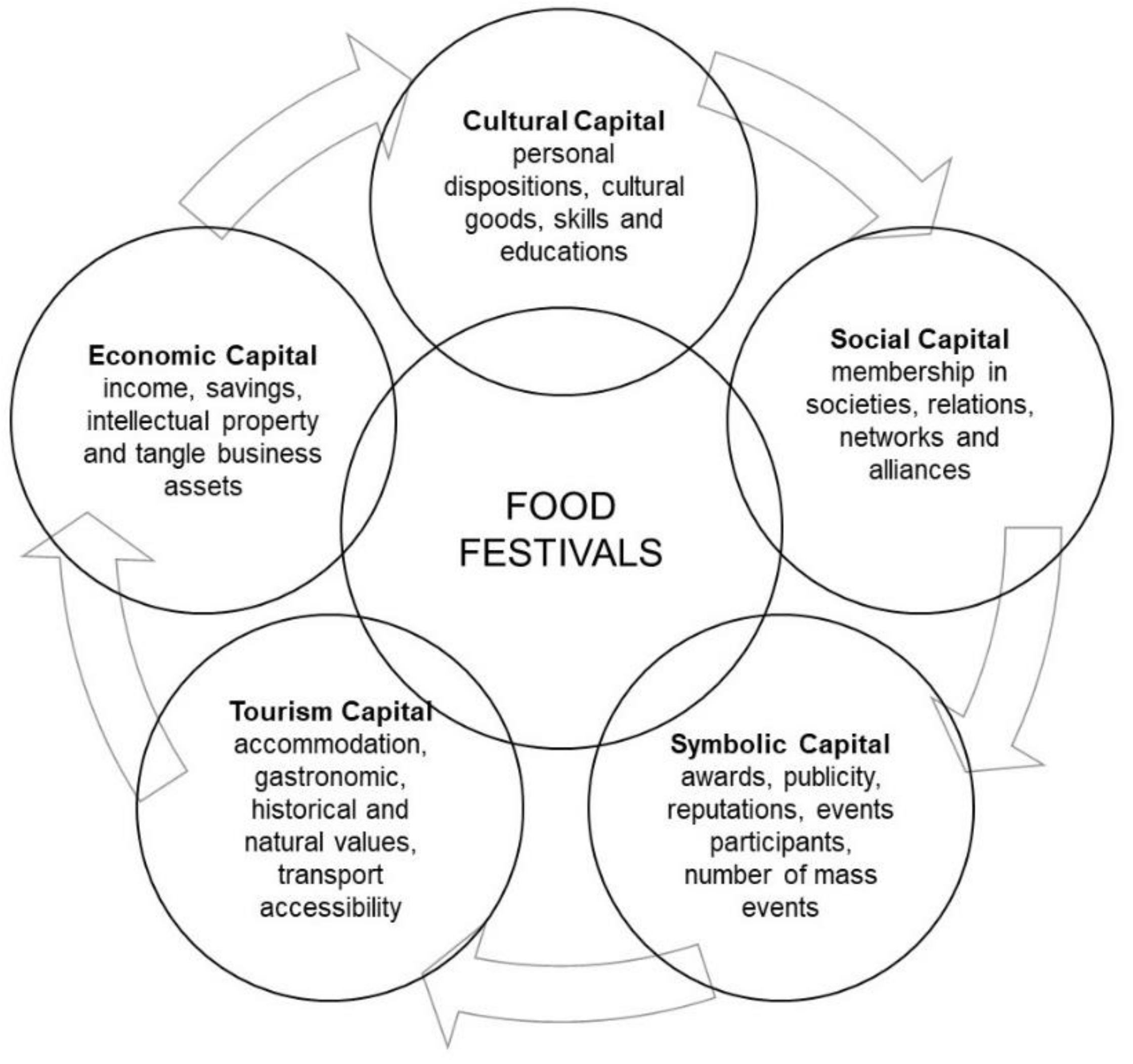

3.1. Conceptual Framework

3.2. Measuring Capitals

- determining capitals;

- selecting empirical features;

- standardizing variables;

- calculating sums of zero unitarization for capitals;

- grouping units of the surveyed population by capital groups and assessment of the sustainability of the indicator structure (k-means classification).

- next feature number,

- next spatial unit number,

- normalized feature j in the spatial unit i,

- value of the feature j in the spatial unit i.

- —average capital value for a type,

- —average capital value for the entire set,

- —standard deviation for the entire set.

4. Results

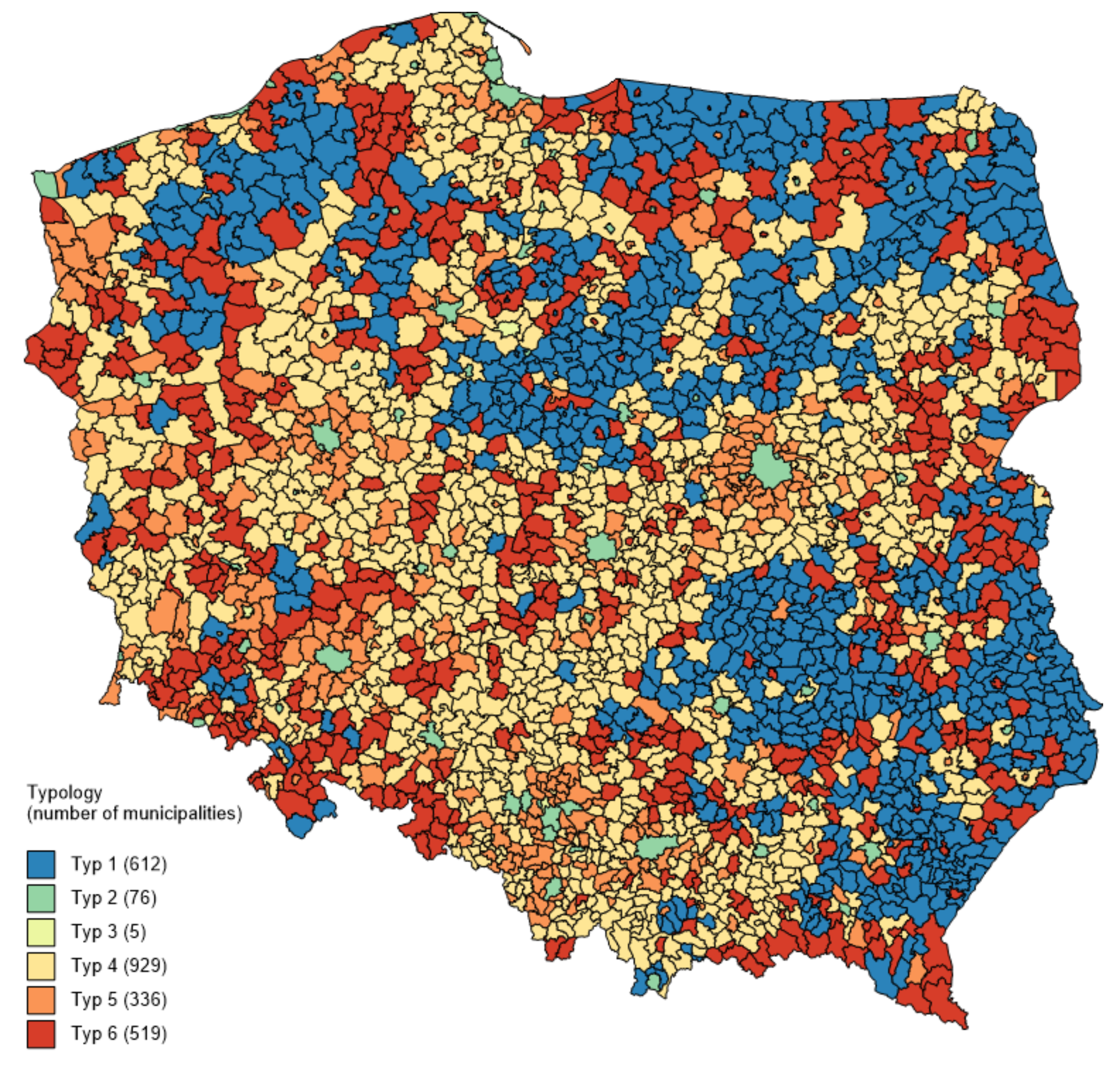

4.1. The Potential of Capitals and Their Sustainability

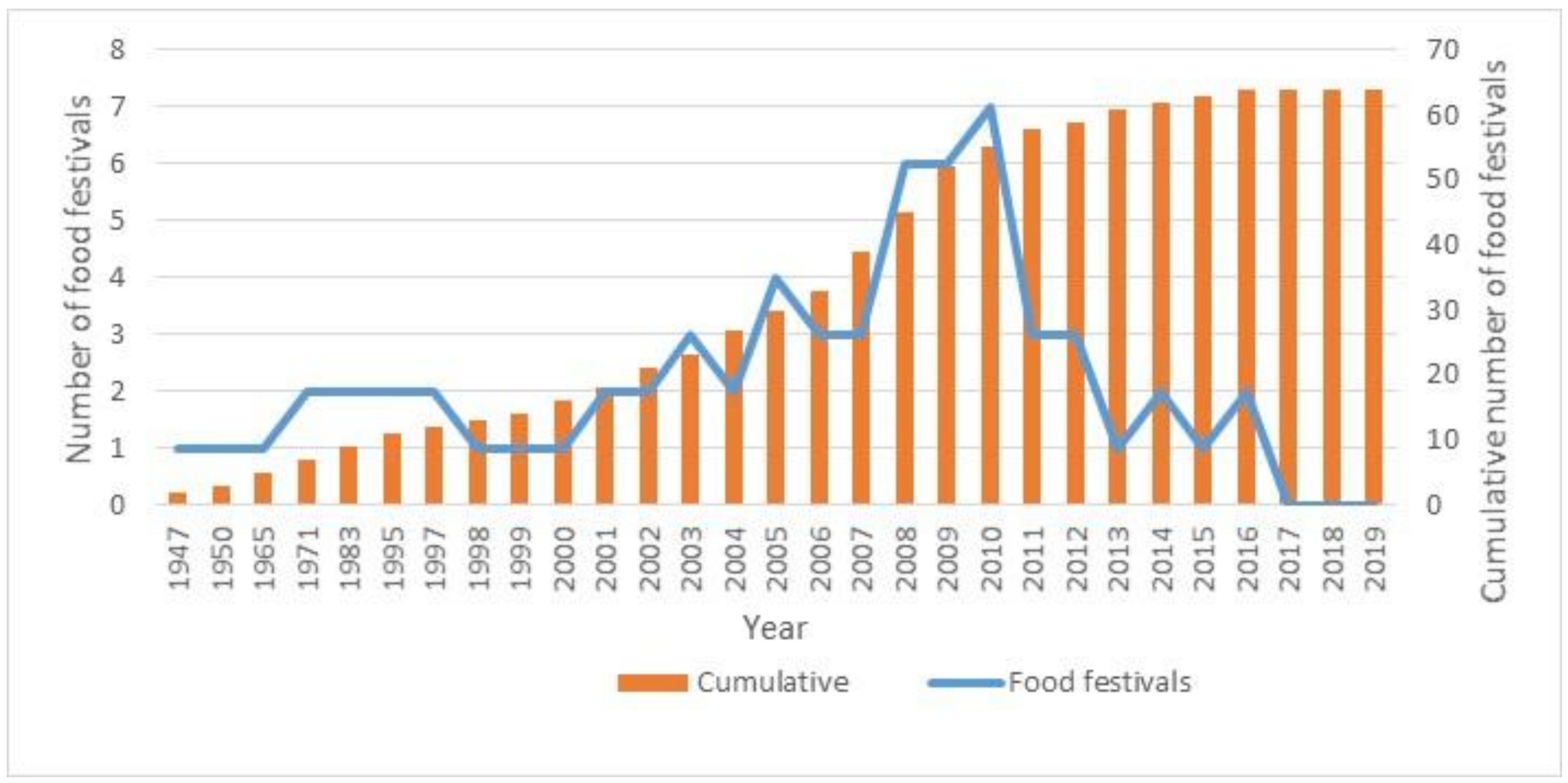

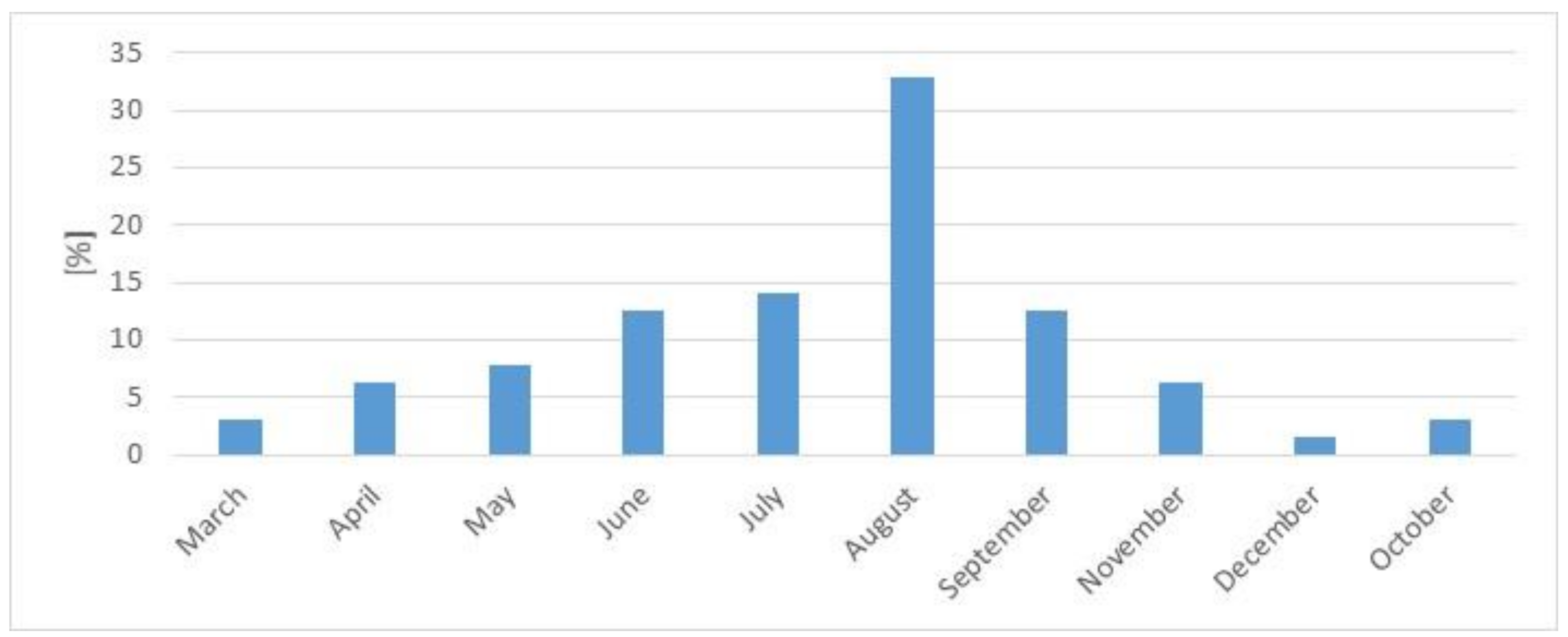

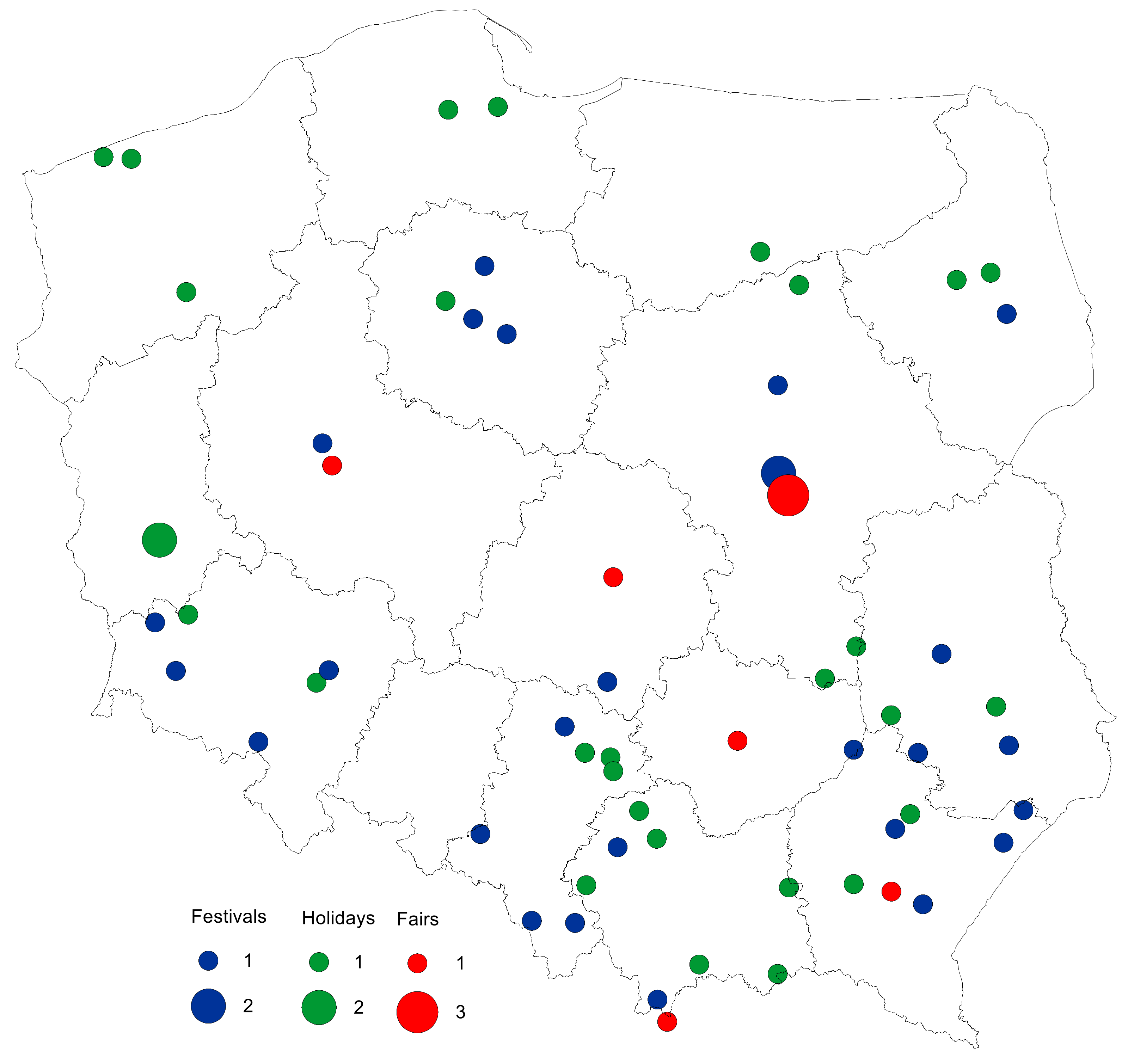

4.2. Location of Food Festivals and the Sustainability of Capital

5. Discussion and Final Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitation and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, P.; Martino, D.; Cai, Z.; Gwary, D.; Janzen, H.; Kumar, P.; McCarl, B.; Ogle, S.; O’Mara, F.; Rice, C.; et al. Agriculture. In Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 497–540. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandratos, N. (Ed.) World Agriculture: Towards 2030/50, Interim Report; An FAO Perspective; Earthscan: London, UK; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, J. Betting on Famine: Why the World Still Goes Hungry, 2nd ed.; New Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013; pp. 150–163. [Google Scholar]

- Moschis, G.P.; Mathur, A.; Shannon, R. Toward Achieving Sustainable Food Consumption: Insights from the Life Course Paradigm. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. (Eds.) Sustainable Culinary Systems: Local Foods, Innovation, and Tourism & Hospitality; Routledge: Auckland, New Zealand, 2013; pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, N. Food Fairs and Festivals. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Food Issues, 1st ed.; Albala, K., Ed.; SAGE Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 565–569. [Google Scholar]

- Jęczmyk, A.; Kasprzak, K. Culinary tourism in Poland in the light of the sustainable development concept. Pol. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 21, 7–14. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, A.; Varley, P. Food tourism and events as tools for social sustainability? J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontefrancesco, M. Food Festivals and Expectations of Local Development in Northern Italy. Ethnol. Actual. 2019, 18, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Litvin, S.; Fetter, E. Can a festival be too successful? A review of Spoleto, USA. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. Hallmark Tourist Events: Impacts, Management and Planning; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992; pp. 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, J.; Cantavella-Jordá, M. Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: The Spanish case. Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, J. Festival and event tourism research: Current and future perspectives. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Sung, H.; Suh, E.; Zhao, J. The effects of festival attendees’ experiential values and satisfaction on re-visit intention to the destination: The case of a food and wine festival. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1005–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohmo, T. Economic impacts of cultural events on local economics: An input-output analysis of the Kaustinen Folk Music. Tour. Econ. 2005, 11, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Larsen, M.Ø. Innovation gaps in Scandinavian rural tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.M.; Kwiatkowski, G. Entrepreneurial implications, prospects and dilemmas in rural festivals. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 63, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, K. Event management research: The focus today and in the future. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brännäs, K.; Hellström, J.; Nordström, J. A new approach to modelling and forecasting monthly guest nights in hotels. Int. J. Forecast. 2002, 18, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Oklevik, O.; Hjalager, A.; Maristuen, H. The assemblers of rural festivals: Organizers, visitors and locals. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J.; Swanson, T.M.; Barbier, E.B.; Holmberg, J.; Wibe, S.; Jones, T.; Mcgehee, W.; Thayer, P.W.; Echenique Larrain, J.; Villavicencio Rivera, M.; et al. Beyond Beef: The Rise and Fall of the Cattle Culture; Banco Mundial: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y. Tourism Development in North Korea: Economical and Geopolitical Perspective. Anatolia 2004, 15, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H. Cultural festivals and regional identities in South Korea. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2004, 22, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, 1st ed.; Richardson, J., Ed.; Westport: Greenwood, IN, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J.; Anderson, T.; Ali-Knight, J.; Jaeger, K.; Taylor, R. Festival management innovation and failure. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2010, 1, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Xiao, H. Culinary tourism supply chains: A preliminary examination. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, G. Social space, social class and Bourdieu: Health inequalities in British Columbia, Canada. Health Place 2007, 13, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarębski, P.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Oklevik, O. Tourism Investment Gaps in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Schefold, B. An empirical investigation of paradoxes: Reswitching and reverse capital deepening in capital theory. Camb. J. Econ. 2006, 30, 737–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss, J. Social Capital Construction and the Consolidation of Civil Society in Rural Areas; Development Studies Institute (DESTIN) Working Paper 00–16; London School of Economics: London, UK, 2001; ISSN 1470-2320. [Google Scholar]

- Pasinetti, L.; Scazzieri, R. Capital theory (paradoxes). In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 1st ed.; Eatwell, J., Durlauf, S.N., Blume, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1990; pp. 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Storberg, J. The Evolution of Capital Theory: A Critique of a Theory of Social Capital and Implications for HRD. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2002, 1, 468–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Social Space and Symbolic Power. Sociol. Theory 1989, 7, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. Am. Prospect 1993, 13, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Social Capital and the Global Economy. Foreign Aff. 1995, 75, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.C. Theory, culture & society. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pret, T.; Shaw, E.; Drakopoulou Dodd, S. Painting the full picture: The conversion of economic, cultural, social and symbolic capital. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 1004–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska-Majkowska, H. Atrakcyjność Inwestycyjna Polskich Regionów: W Poszukiwaniu Nowych Miar; Wydawnictwo Szkoły Głównej Handlowej: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, V. Tourist product. In Tourism Marketing and Management Handbook; Witt, F.S., Moutinho, L., Eds.; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, W. Tourism image: Attribute measurement of state tourism products using multidimensional scaling techniques. J. Travel Res. 1989, 28, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinung, A. Determinants of the attractiveness of tourism region. In Tourism Marketing and Management Handbook; Witt, F.S., Moutinho, L., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Hertfordshire, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.B. Perceived attractiveness of Korean destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 340–361. [Google Scholar]

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Poczta, J. A small-scale event and a big impact—Is this relationship possible in the world of sport? The meaning of heritage sporting events for sustainable development of tourism—Experiences from Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołembski, G. Wyodrębnianie regionów turystycznych. In Kompendium Wiedzy o Turystyce; Gołembski, G., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2002. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. The Impact of Social Structure on Economic Outcomes. J. Econ. Perspect. 2005, 19, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. New Economic Sociology: What Has Been Accomplished, What Is Ahead? Acta Sociol. 1997, 40, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Institutions as Social Constructions: A Framework for Analysis. Acta Sociol. 1992, 35, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.; Swedberg, R. The Sociology of Economic Life, 2nd ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer, B. Journalism, Memory, and the Voice of the Visual. In About to Die: How News Images Move the Public; Zelizer, B., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, K. The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Halfacree, K. Rural space: Constructing a three-fold architecture. In Handbook of Rural Studies; Cloke, P., Marsden, T., Mooney, P., Eds.; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, M. Food Sovereignty: Forgotten Genealogies and Future Regulatory Challenges. J. Peasant Stud. 2014, 41, 959–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattuck, A.; Schiavone, C.; VanGelder, Z. Translating the Politics of Food Sovereignty: Digging into Contradictions, Uncovering New Dimensions. Globalizations 2015, 12, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingali, P.; Aiyar, A.; Abraham, M.; Rahman, A. Transforming Food Systems for a Rising India; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Special events: Defining the product. Tour. Manag. 1989, 10, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukuła, K. Metoda unitaryzacji zerowanej na tle wybranych metod normowania cech diagnostycznych. Acta Sci. Acad. Ostroviensis 1999, 4, 5–31. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Borowicz, A.; Kostyra, M.; Dzierżanowski, M.; Szultka, S.; Wandałowski, M. Atrakcyjność Inwestycyjna Województw i Podregionów Polski 2016; Instytut Badań nad Gospodarką Rynkową: Gdańsk, Poland, 2016. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.H.; Huh, J.H. A novel on transmission line tower big data analysis model using altered K-means and ADQL. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Local Data Bank. Statistics Poland. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Hartigan, J.A.; Wong, M.A.; Algorithm, A.S. A k-means clustering algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C 1979, 28, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, P.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Mai, K. Sensing spatial distribution of urban land use by integrating points-of-interest and Google Word2Vec model. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 825–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T.; Lee, C.K.; Chan, A.C.; Leung, E.M.; Lee, J.J. Social network types and subjective well-being in Chinese older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B: Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonchai, P.; Freathy, P. Cross-border tourism and the regional economy: A typology of the ignored shopper. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegar, J. The issue of land concentration in Polish individual agriculture. Yearb. Agric. Sci. 2009, 96, 256–266. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Ring, A.; Dwyer, L.; Andersson, A.C.; Hall, C.M. Optimizing or maximising? A challenge to sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lin, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S. Sustainability indicators for festival tourism: A multi-stakeholder perspective. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 20, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, C.; Li, Y. Analyzing the effects of an urban food festival: A place theory approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colgado-Fernández, J.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J. Food Festivals and the Development of Sustainable Destinations. The Case of the Cheese Fair in Trujillo (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Capital | Indicator | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | X1 Real estate tax revenue per capita | 2019 |

| X2 Shares in taxes for state budget revenue, personal income tax per capita | 2019 | |

| X3 Share of the registered unemployed persons in the population in the working age | 2019 | |

| Cultural | X4 Expenditure of municipalities’ budget for culture and national heritage per 1000 inhabitants | 2017–2019 |

| X5 Graduates of courses organized by centers of culture per 1000 inhabitants | 2017–2020 | |

| X6 Share of the population with higher education | 2002 | |

| Social (network) | X7 Number of foundations, associations, and social organizations per 1000 inhabitants | 2019 |

| X8 Members of groups (clubs/sections) per 1000 inhabitants | 2019 | |

| X9 Members of sports clubs per 1000 inhabitants | 2019 | |

| Symbolic | X10 Number of participants of mass events per km2 | 2017–2019 |

| X11 Number of participants events-pay entrance per km2 | 2017–2019 | |

| X12 Number of mass events per km2 | 2017–2019 | |

| Tourism | X13 Expenditure on tourism per km2 | 2017–2019 |

| X14 Number of beds per km2 | 2019 | |

| X15 Number of restaurants per km2 | 2019 |

| Type | Capital | Municipalities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Cultural | Social (Network) | Symbolic | Tourism | u ** | u-r | r | Total | ||

| Average Value of the Cluster | % | N | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.233 (----) * | 0.053 (--) | 0.001 (~~~) | 0.092 (~~~) | 0.003 (~~~) | 3 | 74 | 23 | 24.7 | 612 |

| 2 | 0.393 (++++) | 0.152 (++++) | 0.139 (++++) | 0.125 (++) | 0.183 (++++) | 93 | 3 | 4 | 3.1 | 76 |

| 3 | 0.449 (++++) | 0.194 (++++) | 0.688 (++++) | 0.154 (++++) | 0.235 (++++) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 5 |

| 4 | 0.336 (~~~) | 0.059 (~~~) | 0.002 (~~~) | 0.084 (--) | 0.006 (~~~) | 5 | 69 | 26 | 37.5 | 929 |

| 5 | 0.396 (++++) | 0.139 (++++) | 0.012 (~~~) | 0.107 (~~~) | 0.029 (~~~) | 36 | 39 | 26 | 13.6 | 336 |

| 6 | 0.302 (~~~) | 0.076 (~~~) | 0.002 (~~~) | 0.144 (++++) | 0.008 (~~~) | 8 | 60 | 32 | 21.0 | 519 |

| M | 0.314 | 0.075 | 0.009 | 0.103 | 0.014 | |||||

| SD | 0.067 | 0.046 | 0.043 | 0.039 | 0.045 | |||||

| Regions/Location | Type of Food Event | Type of Municipality | Total | Agrarian Fragmentation * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Festivals | Holidays | Fairs | Urban | Urban-Rural | Rural | Ha per Farm | ||

| Dolnośląskie | 4 | 2 | - | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 16.46 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 15.77 |

| Lubelskie | 3 | 3 | - | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 7.73 |

| Lubuskie | - | 2 | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | 21.18 |

| Łódzkie | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | 7.72 |

| Małopolskie | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 4.04 |

| Mazowieckie | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | - | 3 | 8 | 8.57 |

| Podkarpackie | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4.77 |

| Podlaskie | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 12.27 |

| Pomorskie | - | 2 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | 19.16 |

| Śląskie | 4 | 3 | - | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 7.7 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | 2 | 5.67 |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 22.79 |

| Wielkopolskie | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | 2 | 13.56 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | - | 3 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 3 | 30.35 |

| Total | 27 | 29 | 8 | 28 | 17 | 19 | 64 | |

| Type | Characteristic Municipalities | Location of Food Festivals * |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

| Lipsko(u-r), Myszyniec(u-r), Narol(u-r), Krzeszów(r), Dubiecko(r), Sokołów Małopolski(u-r), Lelów(r) |

| 2 |

| Wrocław(u), Lublin(u), Łódź(u), Zakopane(u), Warszawa(u), Rzeszów(u), Białystok(u), Gdańsk(u), Kielce(u), Poznań(u), Rewal(r) |

| 3 |

| Toruń(u) |

| 4 |

| Dobrcz(r), Zławieś Wielka(r), Zamość(r), Radomsko(r), Krzeszowice(u-r), Słomniki(u-r), Charsznica(r), Łącko(r), Zator(u-r), Pilzno(u-r), Mońki(u-r), Irządze(r), Szczytno(r), Trzebiatów(u-r) |

| 5 |

| Osiecznica(r), Świecie(u-r), Zielona Góra(u), Boguchwała(u-r), Korycin(r), Kartuzy(u-r), Ustroń(u), Kuźnia Raciborska(u-r), Żywiec(u), Częstochowa(u), Sandomierz(u) |

| 6 |

| Lwówek Śląski(u-r), Przemków(u-r), Jedlina-Zdrój(u), Janów Lubelski(u-r), Krasnystaw(u), Kraśnik(u), Janowiec(r), Uście Gorlickie(r), Pułtusk(u-r), Lubaczów(u), Janów(r), Kalisz Pomorski(u-r) |

| Hypothesis | Verification Methods | Support |

|---|---|---|

| H1. Food festivals are held mainly in large cities and their neighboring municipalities rather than in peripheral rural areas. | Mapping and analysis of a food festival’s locations using geographic information systems (GIS) | Yes |

| H2. Urban areas have a higher level of capitals and sustainability of capitals of food festivals than rural areas. | Assessment of the sustainability of the indicator structure (k-means classification) | Yes |

| H3. The impact of food festivals on capitals conversion is stronger if there is a high tourism capital in the local environment. | Assessment of the sustainability of the indicator structure (k-means classification) | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zarębski, P.; Zwęglińska-Gałecka, D. Mapping the Food Festivals and Sustainable Capitals: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10283. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410283

Zarębski P, Zwęglińska-Gałecka D. Mapping the Food Festivals and Sustainable Capitals: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10283. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410283

Chicago/Turabian StyleZarębski, Patrycjusz, and Dominika Zwęglińska-Gałecka. 2020. "Mapping the Food Festivals and Sustainable Capitals: Evidence from Poland" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10283. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410283

APA StyleZarębski, P., & Zwęglińska-Gałecka, D. (2020). Mapping the Food Festivals and Sustainable Capitals: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability, 12(24), 10283. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410283