Abstract

Although research on human resource management practices (HRMPs) has been ongoing for many years, studies have actually paid little attention to HRMPs and their contribution to the emotional side of the bottom line or commitment to the external environment, particularly the serial mediation of HRMPs. Hence, to fill this research void, this study extends social exchange theory, broaden-and-build theory and the conservation of resources (COR) theory in the context of green hospitality by proposing a novel conceptual model to test the mediating effects of resilience and commitment between HRMPs (training, empowerment, and rewards) and service providers’ environmental commitment. A quantitative study was performed involving 557 participants at green hotels. The findings show that the components of HRMPs (training, rewards, and empowerment) were found to be crucial tools in encouraging service providers to engage in environmental tasks while green training, empowerment and reward systems can unlock environmental commitment (EEC) for the setting. In addition, environmental commitment increased by the contribution of two mediators, resilience and engagement; and interestingly, rewards did not contribute to the environmental resilience of service providers, while all three HRMPs had a positive influence on work engagement of service providers in the research context.

1. Introduction

In the last few years, the environment has become one of the most important challenges [1,2] and a brand-new development approach of firms [3]. Therefore, this subject has been drawing the attention of many scholars [4] due to the strategic pervasiveness and vitality of developing sustainable organizations [5] via “greening” human resource capital. The green challenge came into play in human resource management, and “green” or “environmental” concepts have been used interchangeably to describe this type of management, which many consider to be key to successfully implementing sustainable growth strategies in an organization [6].

In fact, green human resource management, also called green human resource management practices (HRMPs) in this study, has been shown to have several positive outcomes on environmental and sustainable performance while encouraging service providers to commit to green performance and suggest green services and ideas [7,8,9]. It also inspires people [10] to devote themselves to environmental tasks, and embrace and support green practices within [11], particularly the commitment of service providers in the direction of the environment at the workplace [12].

The commitment of human resources is connected to emotional attachment to the organization, and it also reflects particularly its embracing of organizational values, objectives, and targets [13]. Therefore, when individuals are dedicated to environmental goals and objectives, service providers are expected to exhibit appropriately changed attitudes and also behavior in their attempts to demonstrate their organization’s green values [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]; also, they should make greater efforts in order to meet the green goals of their organization [15].

In addition, service provider commitment is a vital element of the entire service commitment to the environment, which substantially improves the sustainable performance of firms [16] and industries.

In fact, the positive impact of service provider commitment to organizational competitiveness and sustainability and its relevance to individuals’ long-term interests and quality of life have received increasing attention from social-science scholars [17]. The outcomes of environmental commitment have been examined in prior research that has furthered understanding in this field, particularly in examining HRMPs related to service provider environmental commitment, e.g., [12,13,14,15]. Nevertheless, this paper is encouraged by several research gaps in the relevant literature.

According to social exchange theory [18], we argue that the organization’s awareness of and seriousness in practicing environmental policies might lead to reciprocal behavior of workers, such that if they see that they get training parallel to the organization’s vision, which is socially responsible and will provide many benefits to the society or the world, their environmental commitment at work will increase.

Yet, the limited number of studies available in the HRMP field concentrate on the effect of green components on attitudes or emotions, and there is also a need to understand how to boost green-oriented behaviors, e.g., [19]. Thus, the line of studies about the results of HRMPs in terms of service provider environmental commitment is still underdeveloped [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Particularly, connecting the links in the process by which the three components of HRMPs enhance or decrease green hotel service providers’ work commitment is an important process that has to be explored. More important is to seek the “how” and test how both skills and attitudes, i.e., resilience and engagement, are vital for management to advance their knowledge of both mediators in this process in the green hotel setting. This process, however, has not been fully understood by prior research. This paper’s main aim, therefore, is to examine the relationship between HRMPs and service provider environmental commitment in a green setting.

Based on the broaden-and-build theory [21], this study also tries to understand the relationship between organizational resources (i.e., HRMPs) and personal resources (i.e., resilience), which have been used very rarely in the hospitality management literature.

Two important questions are:

- Do HRMPs positively affect service provider environmental commitment in green hotels as they do in other industries?

- Do HRMPs influence service provider environmental commitment via enhancing skills (i.e., resilience) and attitudes or feelings (i.e., work engagement)?

The study provided several important contributions to the hospitality and green management literatures: First, Ardichvili (2011) [22] pointed out that there is a need for a deep empirical investigation of resilience as a personal resource in the area of organizational behavior studies. Avey (2014) [23] also supported that empirical research about antecedents of resilience is rare.

Second, it has been indicated that human resource management practices, i.e., training, empowerment, rewarding relationship with job engagement, are also very important since work engagement research studies are very limited in the management literature in general [24].

Third, the related relationships are sparse in the green management and hospitality literatures in particular. However, keeping and retaining employees, as well as sustaining the green practices to protect the environment, are two of the most important challenges of management and, therefore, understanding the role of human resource management practices on personal resources at the individual level, as well as at group levels, is undeniable.

Fourth, this empirical study is an initial step in exploring HRMPs and service provider commitment in green-oriented hotels in a different geographic area, Turkey, which is a geography different than Western culture where most of the green management studies took place previously.

Fifth, this study additionally makes a contribution to the green-management literature by utilizing two mediators to understand the mediating influences of emotions and skills, service provider resilience and engagement between HRMPs and service provider environmental commitment, in such a setting. As Whetten [25] stated, it is vital for researchers to be able explicate the causal relationships as phenomena by uncovering mediation factors among reasons and consequence constructs.

The research paper is arranged as follows. Following the introduction, the evaluation of literary works and development of theories are offered in the first section. The second part highlights the methodology, encompassing the research study layout, the sample size, and the collection, analysis, and measurement of the information. Consequently, the empirical findings are provided toward the end of the last section. Last but not least, the authors conclude this research by offering both practical and theoretical implications, highlighting the limitations, and providing possible directions for future studies.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Background

Renwick et al. (2013) [6] specified the components of green human resource management (GHRM). GHRM can be viewed in terms of novel research intended to comprehend environmental management by means of the implementation of firms’ HRM practices [26,27].

In this research study, the authors used the three elements—green training, rewards, and empowerment—in order to determine HRMPs. As several researchers have mentioned [28], a vital consequence of an HRM system is service provider commitment to the same firm, revealing an interest in the bottom line, sharing the company’s values, approving its goals, and significant effort in the work setting.

This shows service providers’ internal inspiration, motivation, passion, and responsibilities, and is not pointed out in the company’s task requirements. In the green setting, Perez et al. [10] likewise considered service providers’ internal inspiration, specifying environmental commitment “as an internal, obligation-based inspiration” regarding the environment. Raineri and Paillé [17] noted workers’ sense of collaboration and responsibility with regard to environmental concerns.

Hence, this principle shows service providers’ internal inspiration and is considered as their level of commitment to environmental concerns [12]. Research reveals proof that extremely resilient people have much improved adaptive and coping capabilities when confronted with challenges, including work-associated tension [29]. Howard (2008) [30] highlighted the importance of resilience in safeguarding staff from the negative effects of unfavorable situations at work. Grant and Kinman [31] likewise pointed out resilience’s inevitability for staff members operating in complicated and mentally difficult professions. Despite the need for an extremely resilient and engaged labor force in the current complex personnel scene of service companies, few studies have examined the nexus between discovering HRMPs, work engagement, service provider resilience, and organizational commitment.

Consequently, this research study intends to add to the understanding of service provider resilience and engagement and its function in boosting organizational commitment by making use of social exchange theory, the broaden-and-build theory [21], and the conservation of resources theory [32,33].

Social exchange theory [18] holds that service providers who experience gain from their company’s practices or actions feel obliged to reciprocate them [34], and this highlights the value of studying the primary impacts of reciprocity on long-lasting relationships among shareholders [28]. The attitude of service providers is a fundamental part of HR practices, and for this reason an effective HR strategy could lead to significant and favorable relations of service provider responses in the organizational setting [35].

A limited number of previous studies have found the association between HRMPs and work engagement to be significant in the environmental context [1,10,14]. To exemplify, theory of broaden and build [21] holds firm implications that provide proficiency, meaningfulness, and autonomy will increase favorable feelings among workers. In turn, favorable feelings such as enthusiasm and pride broaden people’s range of understanding, which leads to the advancement of individual resources, incorporating mental and physical resources in time.

Given this reality, the study presumes that HRMPs should conjure a range of favorable feelings among staff members such as support, motivation, identity and autonomy, and self-efficacy by supplying a variety of resources. These favorable emotions have been shown to produce service provider strength or resilience and work engagement [21].

Previous studies have likewise found the association between favorable feelings or emotions and work engagement to be significant [36]. Conservation of resources (COR) theory holds that individuals try to attain, sustain, and secure resources that are of value to them [32,33]. These resources may be items, private qualities, drives, or settings, which are subsequently used by people to safeguard themselves from, or recover, from losses, or to obtain earnings. To put it simply, when people are provided with adequate resources (in the job context), they tend to generate the mental capabilities (or resources) that lead to the development of other resources.

Research has also shown that such people have a greater level of agreement between their organizational and individual goals and are more internally or externally encouraged to attain them [37]. In essence, extremely resilient workers trust in their capabilities and hence end up participating more in their work functions.

2.2. Green Human Resource Management Practices (HRMPs) and Service Provider Environmental Commitment (EEC)

The study follows the theoretical pathway of Emerson (1976) [18] and therefore uses social exchange theory (SET) and explores how the commitment of service providers to their environment is impacted by green HR practices. With regard to SET, workers who take advantage of their company’s actions feel obliged to reciprocate them [34]. Thus, the primary results of interchange in regard to shareholder interactions of an organization are highlighted as they are highly valuable [28].

Behaviors of service providers are among the vital considerations of HRM activities, and for this reason an excellent HRM strategy might lead to significant and favorable interactions among workers [35,38].

Therefore, green HRMPs (e.g., rewards and empowerment) might promote EEC by communicating the service provider’s understanding of green human resource management [5,39]. Green training helps service providers understand how to take in and embrace environment-centered abilities that can yield long-lasting EEC [40].

From a green perspective, the literature on the relationship between green HRM and EEC has not been empirically tested to a large extent. For example, Perez et al. (2009) [10] mentioned how environmental management systems allow green mindsets among environmentally responsible workers to exist and to be reinforced at the workplace. This takes place because staff members operating in green-oriented companies should alter their frame of mind, values, and standards to adjust to the company’s green values (i.e., objectives) [4].

Their routine and active involvement in green-friendly practices enhance business-centered objectives, leading to a sense of concern about EEC [41].

Pinzone et al., 2016, [4] presented empirical findings on how commitment is impacted by human resource practices that center green understanding. Ren et al., 2018, [5] mentioned that payment is deemed to be a part of increasing green-specific results, such as EEC.

Luu (2018) [12] likewise discovered that green rewards for service providers’ responsible acts are related to EEC. In a green organizational culture, specifically when a company takes note of green culture advancement, the leading management establishes systems for training, evaluating service provider practices, and benefits [41] and supplies green procedures and acts to bring in more workers with an environmental orientation [42] and motivate workers to offer green feedback [6,20]. This highlights favorable modifications to service providers’ green understanding, awareness, and abilities, and results in the adoption of a green mindset by staff members at work (EEC).

Thus, the hypotheses below are proposed:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Job training of green hotel service providers is related positively to their EEC.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Rewards for green hotel service providers are related positively to their EEC.

Hypothesis 1c (H1c).

Empowerment of green hotel service providers is related positively to their EEC.

2.3. HRMPs and Service Provider Resilience

To date, efforts to create, examine, and execute HRM practices to foster resilience have been minimal.

Regardless of the proof of a relationship between HRMPs and organizational performance [43], in practice, HRMPs have not been deemed a value-adding element at numerous companies, since the HR function’s contribution is hardly ever determined tangibly [44]. With quick globalization and technological developments, it has actually ended up being crucial for companies to adjust their level of interaction among workers to motivate enthusiasm for business competitiveness [45,46].

Therefore, supporting and developing resilience among staff members are required for adjusting and reacting successfully to green challenges [47], which illuminates studies in the current literature contributing to the matter and shows the important function of service provider resilience in enhancing job outcomes, e.g., [48,49]. Given the developmental nature of resilience, the crucial difficulty external professionals deal with is to recognize the organizational structure and act to reinforce green concepts among workers [50,51].

Studies have suggested that resilient people are much better prepared to manage a continuously altering office [52,53]. Luthans, Vogelgesang, and Lester (2006) [54] indicate that human resources should secure the advancement of mental capital and the resilience of their workers. Other studies also examined in the present research show that it is possible to establish resilience utilizing a range of HR practices. Until now, however, most HRM specialists’ attention on resilience has been focused on training interventions [55]. To the author’s knowledge, the literature is scarce on studies that provide empirical methods to test any direct links, and this has been pointed out in past studies [46,48,56,57]. For instance, Hodliffe (2014) [46] mentioned the function of empowering leadership and involving service providers in cultivating resilience.

In addition, the level to which workers are enabled to take part in such changes and their efforts can develop in accordance with the managerial background and chronologically impact their behavior toward change [58,59,60]. Studies suggest that motivated staff members deal better with modifications and are more versatile and likely to alter procedures [61].

Murray and Donegan (2003) [62] argued that HRMPs promote a beneficial positive environment where workers can develop for the better, which enhances people’s practices and like-mindedness. Findings have shown that workers who are continuously motivated to deal with difficulties and discover ingenious methods of handling modifications are more likely to establish better modification preparedness, which promotes service provider resilience [63].

The main tenets of green reinforcement of workers have been concentrated on dispositional qualities or personal characteristics, specifying this as a character attribute able both to moderate the unfavorable results of tension and to promote adaption [64].

This study is directed by the concept of Luthans et al. (2002) [54], which specifies resilience as enhanced capacity as a result of negativity such as adversity, conflict, or failure or positive experiences such as positive events or progress, and conceives that service employee resilience is resource-utilizing and adaptive in its capability to help in using and establishing organizational resources [65].

Studies investigating the relationships among resilience and other job-related elements seem to suggest the existence both of vibrant and fixed advantages for companies. Advantages arise as a consequence of resilience being strongly related to job organizational outcomes (i.e., satisfaction and organizational commitment) [66]. Further, Luthans et al. [54] discovered that workers’ mental capital adds to job outcomes, instead of investigating resilience and its connection to absence [67]. In relation to past studies, we postulate that promoting and reinforcing green HRM practices can show a favorable association both with the resilience measurement of mental capital and with favorable worker results (e.g., organizational commitment).

HRM practices were found to have important value for service providers, teams, and companies. This in turn improves staff members’ job satisfaction and self-confidence, reduces absenteeism, and increases carrier development, engagement, and enhancement of individual abilities, therefore encouraging the advancement of workers’ mental ability. When workers are permitted to discuss their issues and provide feedback and divergent viewpoints easily without worrying about unfavorable effects, this helps them understand the value of their company [68].

When companies arrange jobs and functions according to higher organizational objectives and functions, this consequently promotes favorable feelings among workers. Based on the broaden-and-build theory [21], favorable feelings cause the advancement of individual mental abilities and hence produce service provider resilience [69,70]. Based on the abovementioned theoretical and literary works, it is anticipated that HRMPs favorably relate to service provider resilience. Thus, the hypotheses below are proposed:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Job training for green hotel service providers is related positively to their resilience.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Rewards for green hotel service providers are related positively to their resilience.

Hypothesis 2c (H2c).

Empowerment of green hotel service providers is related positively to their resilience.

2.4. Relationship between Service Provider Resilience and Work Engagement

Recently, job engagement has attracted considerable attention among practitioners, researchers, professionals, and so forth [36,71,72]. Scientists found a significant impact of job engagement on service providers’ attitudes and behaviors, and on staff members’ job outcomes and commitment [72,73,74].

Job engagement was first conceptualized by Kahn (1990) [75] and put into practice by Maslach, Jackson, and Leiter (1997) [76]. This study is guided by Schaufeli et al.’s (2002) [77] concept of job engagement, which they explain as a favorable, satisfying, job-related mindset. The relevant study provides proof of the intermediary role of mental aspects and work engagement; nevertheless, such studies are still sparse, particularly in the green management area, in support of the function of bottom line resilience as an antecedent of job engagement (Wefald and Downey, 2009) [78].

Past research pointed out that job engagement and organizational resources along with individual qualities are reciprocally connected. Xanthopoulou et al. [37] likewise discovered that organizational resources (e.g., providing power to the bottom line, manager backup, and advancement chances) and individual traits (e.g., self-efficacy and optimism) anticipate job engagement. The literature remains sparse, however, regarding the relationship with service provider resilience.

The relevant literary work reveals that service providers with resilient skills not only are able to cope with internal problems but also have extra abilities to effectively browse through workplace challenges. Resilient people have various favorable qualities, such as an energetic and positive outlook [79], interest, and open mindedness to new tasks and responsibilities [80]. Confident and efficient workers reveal greater preparedness to deal with difficulties in the work environment, which eventually enhances their work engagement. Research reveals that resilient staff members are more successful at establishing good networks, have better patience, and offer feedback and assistance at work [21]. Thus, the hypothesis below is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Resilience of green hotel service providers is related positively to their work engagement.

2.5. Work Engagement and Service Provider Environmental Commitment

Work commitment is a mental state that drives bonding between service providers and companies by controlling staff members’ choice whether to commit to the company and apply their initiative to attain business objectives [81]. Organizational commitment has three components [82]. The first component is affective commitment, described as an “emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organization emotional” [83]. Both affective commitment and job engagement are uncertain, yet commitment is “regarded as an antecedent of various organizationally relevant outcomes, including various forms of prosocial behavior and/or organizational/job withdrawal” [84].

This study considers job engagement as a consequence of job commitment. SET holds that a feeling of responsibility is nurtured in staff members when they would like to do something in order to reciprocate with the organization. [85]. As another component, affective commitment pertains to attachment that is kind of an emotional tie to the employees that provides self-trust to achieve the required direction that improves their health [86]. Additionally, Shuck et al. (2011) [87] found out that job engagement moderates the relationship between affective commitment and intention to leave. Service providers with positive feelings and loyalty to top managers mostly perceive their job in a way that aligns with the vision of the company and wholeheartedly try to achieve their objectives. Previous jobs have actually shown that efficiency is favorable engagement pertaining to commitment [88,89,90]. Thus, the hypotheses below are proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Work engagement of green hotel service providers significantly and positively affects their EEC.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Resilience of green hotel service providers mediates the relationship between job training and EEC.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Resilience of green hotel service providers mediates the relationship between rewards and EEC.

Hypothesis 5c (H5c).

Resilience of green hotel service providers mediates the relationship between empowerment and EEC.

Hypothesis 6a (H6a).

Work engagement of green hotel service providers mediates the relationship between job training and EEC.

Hypothesis 6b (H6b).

Work engagement of green hotel service providers mediates the relationship between reward and EEC.

Hypothesis 6c (H6c).

Work engagement of green hotel service providers mediates the relationship between empowerment and EEC.

Hypothesis 7a (H7a).

Job training of green hotel service providers is positively related to their EEC via their resilience and work engagement.

Hypothesis 7b (H7b).

Rewards for green hotel service providers are positively related to their EEC via their resilience and work engagement.

Hypothesis 7c (H7c).

Empowerment of green hotel service providers is positively related to their EEC via their resilience and work engagement.

2.6. Serial Mediation

It has been reported that staff members demonstrate greater work-engagement levels when they are consistently offered chances to grow and establish themselves within the company [91]. Olivier and Rothmann [92] asserted that “when companies use physical, psychological and cognitive resources for staff members, they will participate in their work functions and might disengage in the lack of these essential resources.” Researchers have also argued that HRMPs establish worker’s abilities and affect their level of effort in the work environment and commitment to the company [93,94]. Park et al., 2013, [95] reported that HRMPs affect work engagement in Korean companies (production, building and construction, IT, and electronics).

Several research studies have shown that staff members end up being engaged when they can use organizational resources, including autonomy, leader support and feedback (for developmental purposes), work versatility, acknowledgment and benefits, as well as an environment of loyalty and trust [96,97,98,99]. Prior research has also suggested that resilient individuals are better able to deal with extraordinary modifications and adjust efficiently to challenging functions, jobs, and scenarios [100].

Resilience helps workers to buffer against tension and enables them to adjust to difficult and vibrant environments [100]. Based on the conservation of resource theory [32,33], researchers have shown that service provider resilience, as an element of individual resources, favorably impacts work engagement [101,102].

Based on broaden-and-build theory [21], we propose that HRMPs promote favorable feelings, which subsequently promotes resilience, leading to work engagement. Hodliffe (2014) [46] asserted that service provider resilience results in greater engagement levels. Schaufeli and Bakker [103] likewise revealed that when companies use development and advancement programs with their staff members, this in turn fosters service provider resilience. We therefore posit that HRMPs offer chances to generate favorable feelings, which in turn adds to service provider resilience, which consequently causes work engagement [37]. Therefore, we assume that service provider resilience moderates the relationship in between HRMPs and work engagement. Song et al. (2014) [104] provide empirical proof of the moderating result of service provider engagement between group performance and HRMP culture in Korean companies.

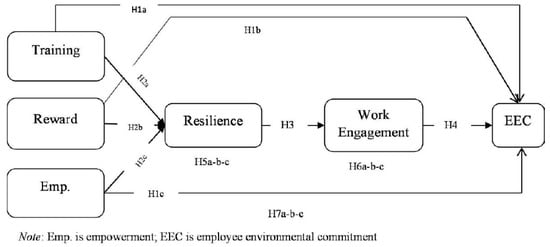

Figure 1 presents the study model (including hypotheses).

Figure 1.

Study model.

3. Method

3.1. Measurements

High performance green work practices were measured by three dimensions: training, empowerment, and rewards. The researchers assessed these using six, five, and five items, respectively, modified from Babakus et al. (2003) [105] and Hayes (1994) [106]. This study used a seven-point Likert-type scale (0 = never; 6 = always) and multiple items to measure the research constructs. Cronbach’s alpha of this construct was recorded as 0.93. Nine items were used to measure service provider work engagement, based on Schaufeli et al. [107]. The Cronbach’s alpha value for this construct was 0.88. The researchers measured environmental commitment with eight items adapted from Raineri and Paill (2016) [17]. Examples of the items include “I feel a sense of duty to support the environmental efforts of my company” and “I strongly value the environmental efforts of my company.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83 for this construct. Green resilience was operationalized using 20 items adapted from Mallak (1998) [108]. An example item was also included in the instrument: “In difficult situations, my service provider tries to look at the positive side.”

All items were initially designed in English. A back-to-back translation method was used to translate the items to Turkish. Two independent native experts in both languages were selected to ensure that all items were cross-linguistically equivalent and developed the same context [109]. After the back-translation, the items were pretested with 10 service providers to check their clarity. The results of the pretest showed that the phrasing, dimension ranges, and series of inquiries were as expected.

3.2. Sample and Procedure

At the time of the research, there were 309 hotels with green certificates in Turkey [109]. More than 50% of those hotels (162) were located in Antalya. Therefore, the participants of this study were full-time service providers from three 4-star and seven 5-star green hotels in the Antalya region of Turkey. The authors planned to include 10% of the population, but unfortunately six hotels did not agree to participate. The participants’ HR managers assigned senior service providers to distribute the questionnaires to the available service providers of these hotels based on judgmental sampling. Once employees filled up the provided surveys, all of the filled questionnaires were placed in the envelopes and then sealed. Then, all completed surveys were placed in the plastic folders provided by the research team. The data collection process was carried out in line with procedural remedies that were utilized to lessen common method bias (e.g., Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff, 2012) [110]. As a final point, the cover page of each questionnaire included information, for instance, “privacy and privacy were guaranteed”, “there were no right or wrong answers to items”, and “taking a part in this research was voluntary but appreciated. Administration completely endorsed participation”. The participating service providers had numerous job positions including front-of-house (front line, food and beverage) and back-of-house (housekeeping, accounting, information technology). Every participant was sent a covering letter with a short paragraph providing a summary of the objective of the study and a guarantee of anonymity [110].

Out of the distributed 590 questionnaires, 19 questionnaires were deleted because of incompleteness, and 14 were deleted due to unengaged responses and missing values. Thus, of the distributed questionnaires, 557 responses were deemed fit for further processing (94% response rate).

Regarding the employees’ demographics (see Table 1), 60% were female and 40% were male; about 52% were aged 18–29 years and 23.5% were aged 30–35 years, with the remainder (23.7%) older than 36. Regarding education, 9.2% had a secondary-school degree, 39.1% a high school, and 41.7% a bachelor’s degree. In terms of tenure at the organization, 33% had worked there for less than a year, 30% for 1–3 years, 32.5% for 4–10 years, and 4.5% had worked for more than 10 years. The full-time participants were mainly from front office 17%, food and beverage and kitchen 25.5%, services departments 13.6%, as well as back of house departments like accounting and maintenance 33%, housekeeping 6.6%, security 4.8%, and so forth.

Table 1.

Profile of respondents.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

Low loading items were primarily omitted from resilience (2), reward (1), environmental commitment (2), and work engagement (1) during the initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) computations [111]. The analysis revealed that all factor loadings were significant, within the range of 0.64 to 0.91 (p < 0.05). The constructs also all demonstrated acceptable composite construct reliability (CCR) (from 0.84 to 0.95; see Table 2). The constructs’ average variance extracted (AVE) (from 0.51 to 0.76) prove that convergent validity was sufficient. The model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (X2 = 2534.03; df = 975; p < 0.01; comparative fit index (CFI) 0.94; goodness-of-fit index (GFI) 0.90; Tucker Lewis index (TLI) 0.96; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) 0.057; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) 0.042), suggesting the variables are distinct constructs. The AVE ratio for every construct was higher than the square of the correlation coefficient between variables; thus, discriminant validity was assured [112].

Table 2.

Measurement parameter estimates.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 presents the study constructs’ mean scores, standard deviations, and correlations. It shows a positive and statistically significant correlation between job training and resilience (RES) (r = 0.196, p < 0.01), service provider reward and RES (r = 0.003, p < 0.01), and service provider empowerment and RES (r = 0.114, p < 0.01). The RES–WE (work engagement) correlation is positive and significant (r = 0.375, p < 0.01). There is also a positive and significant correlation between WE and EEC (r = 0.286, p < 0.01). Therefore, preliminary support is provided for the hypothesized relationships.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

H1–H3 propose that HRMPs’ three dimensions (job training, rewards, and empowerment) have a positive and significant effect on service providers’ environmental commitment (EEC). A hierarchical regression analysis was undertaken to test the hypotheses, with results showing a positive and significant relationship between job training and EEC (β = 0.15, t = 3.57, p < 0.001; Table 4, Model 2), as well as service provider reward and EEC (β = 0.14, t = 3.26 Table 4, Model 3); thus H1a and H1b and H1c are supported.

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression analysis results.

In addition, the relationship between EMP and EEC (β = 0.16, t = 3.166, p < 0.001; Table 4, Model 3) does support H1c.

The results of the regression analysis indicate that the impact of job training on RES is significant and positive (β = 0.10, p < 0.001; Table 5, Model 1), thus supporting H2a. Conversely, the results demonstrate that service provider rewards do not positively and significantly affect RES (β = 0.001, p < 0.001; Table 6, Model 1). Thus, H2b is rejected. Further, empowerment positively and significantly influences RES (β = 0.09, p < 0.001; Table 7, Model 1), providing support for H2c.

Table 5.

Indirect effect of job training.

Table 6.

Result of indirect effect of rewards.

Table 7.

Indirect effect of empowerment.

Regarding H3, RES and WE variables are associated positively, meaning that hotel service providers with higher RES levels will show a higher likelihood for engaging in their work (β = 0.38, t = 9.53, p < 0.001; Table 4, Model 1), which provides support for H3. The results also indicate that RES and EEC are positively and significantly associated, meaning that hotel service providers with higher RES levels tend to have a higher EEC levels (β = 0.29, t = 7.04, p < 0.001; Table 4, Model 5), which provides support for H4.

The hypotheses involving the mediating effect were estimated using the serial mediation model proposed by [113]. The serial mediation analysis results support resilience’s mediating role. In essence, the findings reveal the significance of the indirect effect of training through resilience (β = 0.30; Table 5) because the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval (CI) do not contain 0 (lower bound CI = 0.016; upper bound CI = 0.051), thus supporting H5a. Conversely, RES does not have a mediating role in the REW–EEC relationship (b = 0.001; Table 6). The upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI do not contain 0 (lower bound CI = −0.016; upper bound CI = 0.21), supporting H5b. EMP’s effect on EEC is also mediated by RES (b = 0.02; Table 7). The upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI do not include 0 (lower bound CI = 0.008; upper bound CI = 0.054), thus supporting H5c.

In addition, WE mediates the indirect effects of the three HRMPs’ dimensions on EEC (job training b = 0.019, Table 5; service provider reward b = 0.020, Table 6; service provider empowerment b = 0.03, Table 7), and the upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI do not include 0 for job training (lower bound CI = 0.009; upper bound CI = 0.035), rewards (lower bound CI = 0.008; upper bound CI = 0.040), or empowerment (lower bound CI = 0.018; upper bound CI = 0.065). Therefore, H6a–6c are all supported.

Finally, the test relevant to serial mediation analysis was evidenced. This is based on the job-training and empowerment effects on EEC through RES and WE being significant (job training b = 0.008, Table 5; Table 6; empowerment b = 0.48, Table 7), and the lower and upper bounds of the 95% CI do not include 0 for training (lower bound CI = 0.002; upper bound CI = 0.016), rewards (lower bound CI = 0.005; upper bound CI = 0.006), or empowerment (lower bound CI = 0.002; upper bound CI = 0.016). Therefore, H7a–7c are supported.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Similar to the broaden-and-build, social exchange, and COR theories, our results demonstrate that job training (TRA) and empowerment (EMP) are two important tools that affect service providers’ resilience positively and significantly [21]. However, a reward system at such hotels did not show any influence on their resilience. One possible reason may be the inefficiency of the reward system in encouraging service providers to increase efforts to their highest (extra), in which case they may not be so eager to experience and add value to their personal resources (abilities).

Another important piece of evidence in this study was the significant relationship between service providers’ empowerment and environmental commitment. This might be due to the positive approaches of the managements in green-certificated hotels in Turkey. This finding is interesting geographically, since hospitality organizations or cultural studies conducted in the hospitality organizations indicate that the organizational structures are mostly hierarchical with a paternalistic leadership style [114]. Another reason might be personality issue; service providers may be encouraged or motivated to take initiatives or risks at the bottom line. It does not matter whether it is the top management’s preference to use such an unusual leadership style in green hotels in the geography or whether it is due to some training or personality or other reasons, these points have to be investigated further.

Moreover, based on COR theory, resilience increases work engagement [115]. This important evidence advances knowledge of this relationship in the context of green hospitality. The findings point out that service providers who have good resilience seem to be more active, have more energy, and are proactively devoted to their job. This significant influence of resilience on WE provides support for the limited amount of prior research. This outcome points out that engaged green hotel service providers are more committed to environmental issues.

5.1. Conclusions

Based on broaden-and-build, social exchange, and COR theory, this study’s aim was to examine the effect of HRMPs (training, rewards, and empowerment) on the environmental commitment of full-time green hotel service providers. This relationship is very crucial, since without employee’s commitment to the processes, hotel managers cannot achieve green sustainable objectives. Thus, this empirical work improves our knowledge by providing vital evidence regarding the constructs in the research model with the data obtained from these service providers. Pham et al. (2019) [1] examined HRMPs and service provider commitment in an interactional and direct model and established ability motivation and social exchange theory, advising that future studies should investigate the indirect relationship between HRM and EEC in a green setting, where this study tries to fill this gap.

Two main important questions of the paper were:

- Do HRMPs positively affect service provider environmental commitment in green hotels as they do in other industries?

- Do HRMPs influence service provider environmental commitment via enhancing skills (i.e., resilience) and attitudes or feelings (i.e., work engagement)? A quantitative survey approach was performed involving 557 lower level participants at green hotels in Antalya.

The hypothesis test results showed that the constructs of HRMPs have positive effects on resilience. The findings of the study also showed a significant linkage between resilience and environmental engagement. The outcomes also depicted a positive significant link between HRMPs and environmental engagement which are in accordance with the SET, broaden-and-build theory, COR theory, and showcased that job resources (i.e., resilience) and environmental engagement were boosted by HRMPs. The findings relevant to the mediating role of both resilience and environmental engagement in the relationship between HRMPs and environmental commitment were supported by the data gathered. That is, both constructs serially mediate the effect of HRMPs on environmental commitment.

As a concluding note, this study advances our knowledge regarding hospitality research on HRMPs, resilience, engagement and environmental commitment. The proved outcomes were subject to data gathered in Antalya, Turkey, and put forward valuable theoretical and practical implications.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study provides an important contribution regarding the positive and significant relationship between HRMPs and employees’ green commitment through the serial mediation of resilience and environmental engagement. Our study, through these findings, makes several contributions to the area of green employees’ behaviors and the green hospitality literature. Previous studies on green behavior concentrated on personal environmental attitudes and behaviors in service settings such as voluntary environmental performance at the job or business citizenship behavior for the environment [116,117]. This study focused on employees’ green resilience, engagement, and environmental commitment in hotels. The literature has focused on green resilience as a pervasive and vital level of hospitality organizations. Nevertheless, environmental commitment in the context of full-time employees, particularly at green hotels, has been a neglected topic. Studies have shown that environmental commitment essentially underestimates the important duties of green resilience and engagement in changing consumers into value contributors [118]. Our study was centered on employees’ environmental commitment and explored its mechanism by linking the gaps in green resilience and engagement in the green hotel literature.

A study by Chuang and Chiao (2015) [119] pointed out that employees’ specific actions may be encouraged by HR decisions and actions in conjunction with current tasks for more empirical results regarding how employees’ environmental behavior is affected by human resource management [120]. This study empirically found the relationship between HRMPs and employees’ green resilience to be positive. Additionally, this study found an unexplored mediating mechanism between HRMPs and EEC. Based on social exchange theory, employees’ resilience may perform in between HRMPs and environmental commitment as a mediator. The study fills the gap in literature by conducting serial mediation analysis of employee resilience and engagement [121] and also noted that organizations that follow practices from HRMPs can strengthen the performance of HRMPs.

Using these theories and concepts in the hospitality sector can promote employees’ external attributions about the structure, sustainability, and self-concept of the green image of their hotels/restaurants to form green behavioral intentions. Social exchange theory with regard to the concept of reciprocal relations also provides evidence on the relationship between HRMPs and employees’ green resilience in this study. As green behaviors generally and green resilience specifically are not mutual in employees’ relationships with their organizations in response to the outcomes, social exchange theory, based upon the concept of mutuality, was not efficient enough to shed light on this relationship.

Lastly, the current study also adds a new model for green commitment practices and the green resilience literature. Tourism scholars should not only look for the development of visitors’ pro-environmental tasks, but also identify value and surpass their responses to the organization’s environmentally insufficient behaviors. This study used Turkish green-certificated hotels, which provides a wide contextual understanding of the topic of green resilience.

5.3. Practical Implications

The current study offers some managerial contributions for hospitality leaders. HRMPs are vital; they can lead employees towards green resilience through environmental engagement and commitment. Employees can effectively commit through HRMPs. Hospitality managers should, therefore, understand the impact of HRMPs on employees’ environmental commitment. In this regard, managers should encourage employees to follow the HRMPs and be more careful with the significant relationship between the human resource role and employees’ environmental commitment. Managers should also take feedback from their employees to ensure their HRMPs.

The demands are high in the workplace and should be fulfilled in the specified time period. Thus, it is becoming increasingly important for leaders and managers to create a participatory work climate in complex and uncertain work environments to discuss employees’ perceptions and opinions about environmental practices. The uncertain challenges can restrict employees’ resilience and engagement, which will subsequently negatively affect organizational and employee outcomes. The role of leadership is, therefore, significant in complex and highly competitive environments to encourage environmental commitment, particularly in the hospitality industry. For example, hotel managers need also be aware of the progress of HRMP to encourage environmental engagement, which will result in employees’ environmental commitment in the green service setting.

Despite several difficulties, this study’s findings show that HRMPs can probably play an important role in coping with uncertain challenges through the assurance of environmental commitment in hotels. For example, people will more likely accept greater risks if they perceive environmental commitment [122]. Therefore, instead of focusing on the development of employee safety issues, managers, through HRMPs, can provide employees with an understanding of risks related to green resilience outcomes. Hotel managers should share all possible knowledge with their employees so that in return they will show constructive behaviors. Managers’ leadership styles and behaviors allow employees to recognize the need to advance innovation and support their leaders in managing the barriers and problems when showing service innovative behaviors. Furthermore, to ensure competitive advantage and achieve sustainable development, hotel employees must display green resilience. Hotel managers should, therefore, pay greater attention to building employee resilience and environmental engagement, which in turn will result in green commitment through HRMPs to increase competitive advantages.

Lastly, the practical implications are specifically important for hospitality managers in Turkey, as HRMPs ensure environmental commitment, engagement, and resilience behavior, which can boost the development of the hospitality industry of the country.

6. Limitations and Future Study

Some limitations of this empirical work should be addressed and noted in future research. Although we collected data from 4- and 5-star hotels in the Antalya region of Turkey and employed CFA, there is still the possibility of common method bias because the responses were gathered from employees of the same hotels. Future studies can conduct time-lag studies and gather data from a larger population to better test the causalities.

Secondly, the data collection of our study was limited to only one city in Turkey, which may not recognize cultural differences and influence the hypothesized relationships of the model. Replicating the study with diverse cultural, industrial, and geographical features may provide a better picture of the model and increase generalizability.

Third, this study used employee resilience and engagement as mediators in the hospitality work setting; future studies could measure other antecedents that can trigger green commitment. Further studies could also measure the circumstances under which HRMPs are sustained and how these practices can influence employees’ green resilience over a longer time period. Examining workplace spirituality and organizational or peer support as moderators could strengthen the relationship between HRMPs and green resilience. Additionally, studies in the future may attempt to determine the further effects of green resilience on organizational outcomes, such as profitability.

Finally, in this study we measured HRMPs at the individual level (employees and managers). Further studies could include multilevel research on HRMPs at the organizational level to allow the outcomes to be more generalizable. For those studies, multilevel data could be analyzed using hierarchical linear modelling.

Author Contributions

H.A. completed the introduction and theoretical background sections. T.G. and A.N. wrote the methodology and results sections. M.Y. contributed to reviewing the recent literature. All authors wrote the discussion and results parts and check the latest version of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potocan, V.; Nedelko, Z.; Peleckienė, V.; Peleckis, K. Values, environmental concern and economic concern as predictors of enterprise environmental responsiveness. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 17, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amui, L.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S.; Kannan, D. Sustainability as a dynamic organizational capability: A systematic review and a future agenda toward a sustainable transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzone, M.; Guerci, M.; Lettieri, E.; Redman, T. Progressing in the change journey towards sustainability in healthcare: The role of ‘Green’ HRM. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green human resource management: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyambalapitiya, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. Green human resource management: A proposed model in the context of Sri Lanka’s tourism industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.; Bon, A.T. The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, O.; Amichai-Hamburger, Y.; Shterental, T. The dynamic of corporate self-regulation: ISO 14001, environmental commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior. Law Soc. Rev. 2009, 43, 593–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Chin, T.; Hu, D. The continuous mediating effects of GHRM on employees’ green passion via transformational leadership and green creativity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Employees’ green recovery performance: The roles of green HR practices and serving culture. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1308–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Boiral, O. Pro-environmental behavior at work: Construct validity and determinants. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Garg, P. Learning organization and work engagement: The mediating role of employee resilience. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1071–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzone, M.; Lettieri, E. Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of proactive environmental strategies in healthcare: The mediating effect of “green” HRM. MEDIC 2016, 24, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhu, H.; Cai, Z.; Wang, L. Chinese firms’ sustainable development—The role of future orientation, environmental commitment, and employee training. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineri, N.; Paillé, P. Linking corporate policy and supervisory support with environmental citizenship behaviors: The role of employee environmental beliefs and commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.M. Social exchange theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1976, 2, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Phan, Q.P.T.; Tučková, Z.; Vo, N.; Nguyen, L.H. Enhancing the organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of green training and organizational culture. Manag. Mark. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2018, 13, 1174–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardichvili, A. Invited Reaction: Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Psychological Capital on Employee Attitudes, Behaviors, and Performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B. The left side of psychological capital: New evidence on the antecedents of PsyCap. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2014, 21, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Bakker, A.B.; Gruman, J.A.; Macey, W.H.; Saks, A.M. Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2015, 2, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetten, D.A. What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Seo, J. The greening of strategic HRM scholarship. Organ. Manag. J. 2010, 7, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C. Environmental training and environmental management maturity of Brazilian companies with ISO14001: Empirical evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Mejía-Morelos, J.H. Antecedents of pro-environmental behaviours at work: The moderating influence of psychological contract breach. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, H.F.; Keeley, A.C.; Troyan, P.J. Professional resilience in baccalaureate-prepared acute care nurses: First steps. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2008, 29, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, T.M.; Green, C.J.; Kelly, A.; Ferguson, D. State space sampling of feasible motions for high-performance mobile robot navigation in complex environments. J. Field Robot. 2008, 25, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, L.; Kinman, G. Enhancing wellbeing in social work students: Building resilience in the next generation. Soc. Work Educ. 2012, 31, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Lepak, D.P.; Hu, J.; Baer, J.C. How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1264–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katou, A.A.; Budhwar, P.S.; Patel, C. Content vs. process in the HRM-performance relationship: An empirical examination. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L.H.; Lepak, D.P.; Schneider, B. Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.; Williams, K.; Probert, J. Greening the airline pilot: HRM and the green performance of airlines in the UK. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, G.M.; Côté, R.P.; Duffy, J.F. Improving environmental awareness training in business. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. Relationships between human resource dimensions and environmental management in companies: Proposal of a model. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, E.; Junquera, B.; Ordiz, M. Organizational culture and human resources in the environmental issue: A review of the literature. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003, 14, 634–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramony, M. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between HRM bundles and firm performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Human resource management and performance: Still searching for some answers. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2011, 21, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aveni, R.A. Hypercompetition closes in. Mastering Global Business. Financ. Times Spec. Rep. 1998, 6, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hodliffe, M.C. The Development and Validation of the Employee Resilience Scale (EmpRes): The Conceptualisation of a New Model; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Lin, J.; Chen, Z.; Megharaj, M.; Naidu, R. Green synthesized iron nanoparticles by green tea and eucalyptus leaves extracts used for removal of nitrate in aqueous solution. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 83, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.; Dahdah, M.; Norman, P.; French, D.P. How well does the theory of planned behaviour predict alcohol consumption? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, W.J. Resilience and engagement in mental health nurses. Ph.D. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.C.; Luecken, L.; Lemery-Chalfant, K. Resilience in common life: Introduction to the special issue. J. Personal. 2009, 77, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Reed, M.J. Resilience in development. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., López, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Taylor, M.S.; Seo, M.G. Resources for change: The relationships of organizational inducements and psychological resilience to employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward organizational change. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Feldman Barrett, L. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1161–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Vogelgesang, G.R.; Lester, P.B. Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2006, 5, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.L.; Liu, Y.; Tarba, S.Y. Resilience, HRM practices and impact on organizational performance and employee well-being. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2466–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pang, F.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. Green synthesis of nanostructed Ni-reduced graphene oxide hybrids and their application for catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol. Coll. Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2015, 464, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, R.; Selart, M.; Espedal, B.; Johansen, S.T. The production of trust during organizational change. J. Chang. Manag. 2005, 5, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S. Personality, context, and resistance to organizational change. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2006, 15, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D.J.; Meyer, J.P.; Topolnytsky, L. Employee cynicism and resistance to organizational change. J. Bus. Psychol. 2005, 19, 429–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R. Change management—Or change leadership. J. Chang. Manag. 2002, 3, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.; Donegan, K. Empirical linkages between firm competencies and organisational learning. Learn. Organ. 2003, 10, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundblad, F.; Älgevik, T.; Wanther, O.; Lindmark, C. Leading Change without Resistance: A Case Study of Infrafone; Department of Project, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Linköping University: Linköping, Sweden, 2013; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wagnild, G.M.; Young, H.M. Development and psychometric. J. Nurs. Meas. 1993, 1, 165–17847. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, D.; Manfredini, D. Family and school environmental predictors of sleep bruxism in children. J. Orofac. Pain 2013, 27, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Norman, S.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B. The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate employee performance relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2008, 29, 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Avey, J.B.; Patera, J.L.; West, B.J. The implications of positive psychological capital on employee absenteeism. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2006, 13, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. Green citizenship and the social economy. Environ. Politics 2005, 14, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Thompson, J.A. The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the double-edged sword of deeply meaningful work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2009, 54, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Sedlacek, W.E. The presence of and search for a calling: Connections to career development. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 70, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadi, M.Y.; Fernando, M.; Caputi, P. Transformational leadership and work engagement. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, M.; Van den Broeck, A.; De Witte, H. Do job resources affect work engagement via psychological empowerment? A mediation analysis. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2013, 29, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalabik, Z.Y.; Van Rossenberg, Y.; Kinnie, N.; Swart, J. Engaged and committed? The relationship between work engagement and commitment in professional service firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 1602–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; van den Heuvel, M. Leader-member exchange, work engagement, and job performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 754–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P.; Zalaquett, C.; Wood, R. Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources; Scarecrow: Lanham, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wefald, A.J.; Downey, R.G. Job engagement in organizations: Fad, fashion, or folderol? J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.; Kremen, A.M. IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, C.E.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Taylor, S.F. Adapting to life’s slings and arrows: Individual differences in resilience when recovering from an anticipated threat. J. Res. Personal. 2008, 42, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R. Organizational Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, W.H.; Schneider, B. The meaning of employee engagement. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 1, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaccio, A.; Vandenberghe, C. Perceived organizational support, organizational commitment and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuck, B.; Reio Jr, T.G.; Rocco, T.S. Employee engagement: An examination of antecedent and outcome variables. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2011, 14, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; De Jonge, J.; Janssen, P.P.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and engagement at work as a function of demands and control. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2001, 27, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 43, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardsen, A.M.; Burke, R.J.; Martinussen, M. Work and health outcomes among police officers: The mediating role of police cynicism and engagement. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2006, 13, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glen, C. Key skills retention and motivation: The war for talent still rages and retention is the high ground. Industrial Commer. Train. 2006, 38, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothmann, S.; Olivier, A.L. Antecedents of work engagement in a multinational company. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2007, 33, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, J. Predictors of organizational commitment in India: Strategic HR roles, organizational learning capability and psychological empowerment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1782–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.K.; Anantharaman, R.N. Influence of HRM practices on organizational commitment: A study among software professionals in India. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2004, 15, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Johnson, K.R.; Chaudhuri, S. Promoting work engagement in the hotel sector: Review and analysis. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Joo, H.; Gottfredson, R.K. What monetary rewards can and cannot do: How to show employees the money. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvaas, B.; Dysvik, A. Exploring alternative relationships between perceived investment in employee development, perceived supervisor support and employee outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2010, 20, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, C.; Alfes, K.; Gatenby, M. Employee voice and engagement: Connections and consequences. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2780–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S.; Fisher, M.; Haddad, A. To be engaged or not to be engaged: The antecedents and consequences of service employee engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. The Promotion of Resilience in the Face of Adversity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Olugbade, O.A. The effects of job and personal resources on hotel employees’ work engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, S.; Schuckert, M.; Kim, T.T.; Lee, G. Why is hospitality employees’ psychological capital important? The effects of psychological capital on work engagement and employee morale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. Work Engagem. A Handb. Essent. Theory Res. 2010, 12, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.H.; Kim, W.; Chai, D.S.; Bae, S.H. The impact of an innovative school climate on teachers’ knowledge creation activities in Korean schools: The mediating role of teachers’ knowledge sharing and work engagement. KEDI J. Educ. Policy 2014, 11, 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Babakus, E.; Yavas, U.; Karatepe, O.M.; Avci, T. The effect of management commitment to service quality on employees’ affective and performance outcomes. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R.H.; Pisano, G.P. Beyond world-class: The new manufacturing strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1994, 72, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallak, L. Putting organizational resilience to work. Ind. Manag. 1998, 40, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- McGorry, S.Y. Measurement in a cross-cultural environment: Survey translation issues. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2000, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cömert, M.; Özata, E. Green star under environmental sustainable tourism project sensitivity. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2016, 9, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycan, Z. Human resource management in Turkey-Current issues and future challenges. Int. J. Manpow. 2001, 22, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.A.; Busser, J.A. Impact of service climate and psychological capital on employee engagement: The role of organizational hierarchy. Int. J. of Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, H.; Ho Park, S.; Joon Lee, S. Hydraulic strategy of cactus trichome for absorption and storage of water under arid environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lotz, S.L.; Tang, C.; Gruen, T.W. The role of perceived control in customer value cocreation and service recovery evaluation. J. Serv. Res. 2016, 19, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Chuang, C.H.; Chiao, Y.C. Developing collective customer knowledge and service climate: The interaction between service-oriented high-performance work systems and service leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renwick, D.W.; Jabbour, C.J.; Muller-Camen, M.; Redman, T.; Wilkinson, A. Contemporary developments in Green (environmental) HRM scholarship. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2016, 27, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C.; Bowen, D.E. Reflections on the 2014 decade award: Is there strength in the construct of HR system strength? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.B.; Sarasoja, A.L.; Galamba, K.R. Sustainability in facilities management: An overview of current research. Facilities 2016, 34, 535–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).